Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Johannes TINCTORIS - Expositio Manus

Uploaded by

Daniel Pereira VolpatoCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Johannes TINCTORIS - Expositio Manus

Uploaded by

Daniel Pereira VolpatoCopyright:

Available Formats

EXPOSITIO MANVS

An exposition of the hand according to Master Johannes Tinctoris, licentiate in laws and chaplain to the King of Sicily

To Johannes de Lotinis, a youth consummately adorned with the finest character and numerous noble skills, Johannes Tinctoris, least among music teachers, sends fraternal good wishes.

Prologue: The first thing, O youth of the most shining talent, that a well-organized instructor in any skill delivers to young men keen to learn, is the milk that is, the sweetness of certain straightforward principles, lest, if he should offer them the gall that is, the bitterness of difficulty right from the beginning, he put them off through loss of confidence. Thus it was that a learned musician from Italy, a man of considerable and lofty abilities, with great wisdom put together the principle of the hand, to provide a starting-point in the form of a simple set of instructions, handed down, as it were, for the use of anyone intending to apply himself to the art of sound. Encouraged by these same motives, I have resolved to offer a simple explanation of this hand at the outset, hoping to deal with more difficult matters at a later stage. And I have decided that this exposition should itself be dedicated to your most gracious and noble name, not as a singer ignorant of his own hand, since I know you to be highly proficient in this skill and there is no more dreadful insult with which to charge a musician than the claim that he does not know his hand but as my dearest friend and colleague, beseeching you most earnestly that you might deign to accept this humble work as a gift, and that you might read it thoroughly in the same spirit of goodwill as that in which I offer it to you for your studies.

Chapter 1: On the definition of the hand and its distinguishing features The hand is a concise and useful teaching method, demonstrating comprehensively the qualities of musical pitches. In this context, moreover, it is called the hand as from the container rather than the content, for every hand the outermost recognized member of the human body, according to the physicians, located on the forearm contains that teaching in the tips and joints of its fingers. For indeed on this bodily hand there are five digits, that is to say the thumb; index finger; middle, which is commonly called the large finger; medical [ring] finger; and the ear finger, commonly known as the little finger. Of these the first, that is, the thumb, has one tip and two joints; each of the others, however, has one tip and three joints. Since there are four of these latter, and since four times four make sixteen, together with the three previously mentioned this makes a total of nineteen. These nineteen, sharing an equal status, are ascribed to nineteen musical positions through intrinsic visual association; but the final joint of the middle finger is assigned to the final position, which is the twentieth, through extrinsic relationship, as will become clearer below. And although this teaching method can be set up using either hand, it is nevertheless universal standard practice to use the left hand,

because it is more convenient to indicate the musical positions on this left hand with the index finger of the right. Having said this, there are some who find it most convenient to indicate the positions on the left thumb with the index finger of the same, and the positions on the remaining fingers similarly with the thumb of the same. As a result, they use only the one hand, that is, the left, in this particular method of instruction. Furthermore, this teaching hand is also known by another name, the gamma, from this letter which is called gamma by the Greeks. And this for good reason, since naming takes place after that which is the more worthy, but that which precedes is seen to be the more worthy; so, since on the hand gamma, that is G, comes first, it is proper that the hand be named the gamma after it. And in my opinion the creator of this method, wishing it to be called by this name, adopted the name of the Greek letter by itself, so that he could properly honour the Greeks as the greatest originators of the art of music, from whom the Latins received this same art. In this system of hand-teaching, then, there are seven topics to be considered, which is to say: positions, clefs, pitch-syllables, properties, hexachords, mutations, and intervals; and I have decided to treat each of these under its own heading for ease of reference.

Chapter 2: On positions With respect to the first topic: a position is the location of musical pitches. Furthermore, there are twenty such positions on our hand, which are most conveniently set out on the tips and joints of the digits in the following way: The first is ut on the tip of the thumb. The second is A re on the second joint of the thumb. The third is mi on the first joint of the thumb. The fourth is C fa ut on the first joint of the index finger. The fifth is D sol re on the first joint of the middle finger. The sixth is low E la mi on the first joint of the ring finger. The seventh is low F fa ut on the first joint of the little finger. The eighth is low G sol re ut on the second joint of the little finger. The ninth is high A la mi re on the third joint of the little finger. The tenth is high fa mi on the tip of the little finger. The eleventh is C sol fa ut on the tip of the ring finger. The twelfth is D la sol re on the tip of the middle finger. The thirteenth is high E la mi on the tip of the index finger. The fourteenth is high F fa ut on the third joint of the index finger. The fifteenth is high G sol re ut on the second joint of the index finger. The sixteenth is highest a la mi re on the second joint of the middle finger. The seventeenth is highest fa mi on the second joint of the ring finger. The eighteenth is c sol fa on the third joint of the ring finger. The nineteenth is d la sol on the third joint of the middle finger. The twentieth is e la above the same joint, that is, the third of the middle finger, on the outside, as is shown in the following diagram:

Moreover, of these twenty positions described above ten are lines and ten are spaces, organized alternately. A line, then, is a position produced by a straight protraction drawn in some colour, which in this context is more often called a rule, because it is ruled in a straight direction. A space is a position remaining above or below a line. Hence there are some who call ut 'on the line', A re 'in the space', and so on alternately with the others. But it is the greatest error to speak in these terms, since ut is the line itself, and A re is the space itself, and so on alternately with the rest; they cannot, therefore, be said to be positioned 'on' the line or 'in' the space. And so we should say: ut is a line A re is a space mi line C fa ut space D sol re line low E la mi space low F fa ut line low G sol re ut space high A la mi re line high fa mi space C sol fa ut line D la sol re space high E la mi line high F fa ut space high G sol re ut line highest a la mi re space highest fa mi line

c sol fa space d la sol line e la space Of these twenty positions, however, only one is the lowest, that is, ut, since in that position resides the lowest pitch. There are seven low positions, that is, those contained within the first complete ordering of cleffing letters, which is to say from A re inclusive through to the first A la mi re exclusive; and these are so called because they contain the low pitches. There are seven high positions, that is, those contained within the second complete ordering of cleffing letters, which is to say from the first A la mi re inclusive through to the second exclusive; and these are called 'high' since their pitches are high. There are five highest positions, that is, those which are contained within the third, albeit incomplete, ordering of cleffing letters, which is to say from the second a la mi re through to e la inclusive; and these are called 'highest' because in them are positioned the highest pitches. But some of these positions without their qualifying adjectives have the same name, such as low F fa ut and high F fa ut, low G sol re ut and high G sol re ut, high A la mi re and highest a la mi re, high fa mi and highest fa mi; and so, in order that they may be generally distinguished by those unaware of the differences between low, high and highest, low E la mi, F fa ut and G sol re ut, high A la mi re, and high fa mi are commonly known as 'bottom' notes; and again, high E la mi, F fa ut and G sol re ut, highest a la mi re, and highest fa mi are commonly called 'top' notes, as is shown in the following diagram:

Chapter 3: On clefs With respect to the second topic: a clef is the sign of a line- or space-position. For each one of the positions on our hand has its own clef, distinguished from the others by its name, position, or form. There are, then, just seven letters of the alphabet that make up clefs of this kind, which is to say A, B, C, D, E, F and G. Hence, since we have twenty positions, so that there may also be twenty clefs, these seven letters are all repeated once in order, and then five of them once again. The last of them, however, that is, G, albeit in a different form and under a

different name, is placed in front of all of these, for reasons to be explained below. As a result, since twice seven plus five plus one make twenty, these seven letters in twenty positions, by means of the stated repetitions, make twenty clefs. To the first position, therefore, namely ut, is assigned this letter , which differs from the rest in both name and form, because it is Greek; and it is called the lowest clef, taken up, as it were, by the lowest position. To the second position, that is to say A re, is assigned A. To the third, namely mi, [B]. To the fourth, that is to say C fa ut, C. To the fifth, namely D sol re, D. To the sixth, that is to say low E la mi, E. To the seventh, namely low F fa ut, F. To the eighth, that is to say low G sol re ut, G. And these seven letters are upper-case, distinguished from each other by name; the clefs are termed 'low', serving, as it were, the low positions. Next, to the ninth position, namely high A la mi re, through repetition is allocated A. To the tenth, that is to say high fa mi, is allocated [B], in two-fold form on account of the twofold property of the pitches occurring together in it. To the eleventh, namely C sol fa ut, C. To the twelfth, that is to say D la sol re, D. To the thirteenth, namely high E la mi, E. To the fourteenth, that is to say high F fa ut, F. To the fifteenth, namely high G sol re ut, G. And these seven letters repeated for the first time are also distinguished from each other by name, but distinguished from the seven aforementioned by position and not form, since they are uppercase just like the first ones, except that where previously they were applied to lines they are here applied to spaces, and vice versa; and the clefs are termed 'high', assigned, as it were, to the high positions. Then to the sixteenth position, that is to say highest a la mi re, through further repetition is assigned a. To the seventeenth, namely highest fa mi, also in two-fold form on account of the two-fold property of the pitches coinciding in it. To the eighteenth, that is to say c sol fa, c. To the nineteenth, namely d la sol, d. To the twentieth, that is to say e la, e. And these five letters repeated for the second time, like the others, are distinguished from each other by name, and are distinguished from the first five of the same name in form also, since these first are upper-case, whereas the last five are lower-case. This distinction of form is necessary, since those letters which are applied in the first set to lines and spaces have also been applied here to lines and spaces in a similar ordering. These last five, however, are distinguished from the second five of the same name in both form and position, for the second set, like the first, uses upper-case letters, whereas the last set uses lower-case; and those which are found in the second set on lines are here in spaces, and vice versa. Again, the 'highest' clefs are so called because they are assigned to the highest positions, as is shown in this diagram:

This said, however, as far as notation is concerned not all of these clefs are in use; for in order to understand all the positions, no matter many there may be, it is sufficient to apply only one clef, since, having learned one position by means of its sign, it is entirely straightforward to learn the rest, both above and below, because the progression from one to another must follow its fixed and organized scheme. And although any composer could adopt whichever of these twenty clefs he preferred in his notation, I have nevertheless found only six in use. The first is for ut, whose name, just as its form, is Greek, in order to bestow due honour on the Greeks, as has been explained. The second is for mi and both positions of fa mi whenever mi is sung there and this is called 'square' from its form, because it is square-shaped at the bottom. There are many, however, who notate this clef thus , but incorrectly; for this, indeed, is the proper sign of the chromatic semitone. The third is F for low F fa ut: previous generations once used this clef adopting the form of the proper letter itself, as is shown in ancient manuscripts; but for what reason I know not modern musicians, departing from the footsteps of their ancestors, notate this clef thus or thus , these being common in plainchant; or thus , also in plainchant; or thus ,

especially in composed music, although more frequently it is written void, like this . It is, however, of no consequence either way whether it is void or filled, as in the latter or former case; or even half one and half the other, as here .

The fourth is for both positions of fa mi whenever fa is sung there; and this is called 'round' from its form, because it is round at the bottom. There is a distinction, therefore, between round and square both in form and name. Nor should we pass over the fact that we also use this fourth clef, that is to say round , in all positions where fa is irregularly sung, as is shown in virtually all the works of composers. The fifth is C for C sol fa ut, whose strict letter form has been altered for I know not what reason; for in all music, especially plainchant, if it is filled it is notated like this ; but if it is void, in composed music, it is like this , although it is of no consequence if it is filled or void in either the latter or former case. The sixth is G for high G sol re ut; the use of this clef, however, is rare in composed music, and even rarer in plainchant, since this particular position is not indicated except in cases where C sol fa ut is missing, and this occurs only very rarely. And so that the function of these cleffing letters can be understood concisely, they may be defined in their correct order as follows:

is the clef of

ut.

A is the clef of A re and both positions of A la mi re.

is the clef of mi and both positions of fa mi, which is two-fold, namely square and round. Square is the clef of mi and both positions of fa mi, indicating that in that place

mi should be sung through hard . Round is the clef of both positions of that in that place fa should be sung through soft .

fa mi, indicating

C is the clef of C fa ut, C sol fa ut, and c sol fa. D is the clef of D sol re, D la sol, and d la sol. E is the clef of both positions of E la mi, and e la. F is the clef of both positions of F fa ut. G is the clef of both positions of G sol re ut.

Chapter 4: On pitch names With respect to the third topic: pitch is the sound formed from either natural or artificial instruments. Moreover, there are six universally applicable pitch names, that is to say ut, re, mi, fa, sol, and la; and we can define these in their correct order as follows: Ut is the first pitch name, standing a tone away from the second. Re is the second pitch name, standing a tone away from the first, and the same distance from the third. Mi is the third pitch name, standing a tone away from the second, and a minor semitone from the fourth. Fa is the fourth pitch name, standing a minor semitone from the third, and a tone from the fifth. Sol is the fifth pitch name, standing a tone away from the fourth, and the same distance from the sixth. La is the sixth and final pitch name, standing a tone away from the fifth. And although, as I have just said, there are only six universally applicable pitch names, nevertheless, since in many of the positions on our hand a number of different pitch names are located through repetition, it turns out that on this hand forty-two pitch names are found: One in ut, namely ut. One in A re, namely re. One in mi, namely mi. Two in C fa ut, namely fa and ut. Two in D sol re, namely sol and re. Two in low E la mi, namely la and mi. Two in low F fa ut, namely fa and ut. Three in low G sol re ut, namely sol, re and ut. Three in high A la mi re, namely la, mi and re. Two in high fa mi, namely fa and mi. Three in C sol fa ut, namely sol, fa and ut. Three in D la sol re, namely la, sol and re. Two in high E la mi, namely la and mi.

Two in high F fa ut, namely fa and ut. Three in high G sol re ut, namely sol, re and ut. Three in highest a la mi re, namely la, mi and re. Two in highest fa mi, namely fa and mi. Two in c sol fa, namely sol and fa. Two in d la sol, namely la and sol. One in e la, namely la. Again, of these forty-two pitch names only one is the lowest, that is to say ut in ut, because, relative to the others above, it sounds the lowest. The rest, then, are low, high, or highest. The low pitch names are all those that are contained in this hand of ours from A re inclusive through to high A la mi re exclusive; and they are so called because, relative to the others above, they sound low. The high pitch names are all those that are contained in this hand of ours from high A la mi inclusive through to highest a la mi re exclusive; and they are so called because, relative to the others below, they sound high. The highest pitch names are all those that are contained in this hand of ours from highest a la mi re through to e la inclusive; and they are so called because they sound higher than the high ones, or above the high ones, as is shown in the following diagram:

Chapter 5: On properties With respect to the fourth topic: a property is a certain individual quality possessed by pitches which are to be strung together into hexachords. There are, moreover, three properties, namely hard , natural, and soft .

Hard is the first property, through which ut is sung in all positions whose clef is G; and from this note the other five pitches are then derived in their correct order. And it is called hard because through that property mi is sung in any position whose clef is square ; and this mi is hard, that is harsh, in comparison with the fa sometimes found in the same position, which is to be sung through soft . Natural is the second property, through which ut is sung in all positions whose clef is C; and from this note the other five pitches are then derived in their correct order. And it is called natural because all the pitches of this particular property remain in a fixed and stable scheme, just as with natural matter. Hence the saying, 'That which nature has given, nobody can take away.' Soft is the third property, through which ut is sung in all positions whose clef is F; and from this note the other five pitches are derived in their correct order. And it is called soft because through that property fa is sung in any position whose clef is round ; and this fa is soft, that is sweet, in comparison with the mi sometimes found in the same position, which is to be sung through hard . From this, so that you may commit the fundamental clefs of these properties more firmly to memory, take note of this verse: 'C gives natural, F soft , and G hard.' And at this point it should be noted that there is a great difference between square and hard , and between round and soft : for square and round are the names of clefs, so called from their form, as has been shown above in Chapter 3; but hard and soft are the names of properties, so called from the quality of the pitch names fa and mi that are to be sung in the positions of the aforementioned clefs. The common form of this letter 'b', that is to say with a rounded rounded bottom, remains in both round and soft for two reasons: firstly because that which is soft, by which we understand sweet, is more worthy than that which is hard, that is, harsh; and secondly because, since round and square occur together in one and the same position that is, in both positions of fa mi round comes first. And it is certainly the most fitting reasoning that the more worthy should take precedence, since it takes the primary form. In order to differentiate from this common form of the letter in question, another was invented, that is to say with a squared bottom, so that, through their different forms, different positions and different properties, indicated by means of this same letter, could be clearly recognized.

Chapter 6: On hexachords With respect to the fifth topic: a hexachord is an ordered string of pitch names, deriving from one position and proceeding to another through any one of the properties. And since, as I have said above, there are three properties, namely hard , whose fundamental clef is G, natural, whose fundamental clef is C, and soft , whose fundamental clef is F, and since there are three Gs in our hand, namely , which is G in Latin, the G of low G sol re ut, and the G of high G sol re ut, and two Cs containing ut, namely the C of C fa ut and the C of C sol fa ut, and two Fs, namely the F of low F fa ut and the F of high F fa ut, given that three plus twice two make seven, it is inevitable that there are seven hexachords in this hand of ours, that is to say three of hard , two natural, and at two of soft . The first hexachord, then, is from the ut of ut through to the la of low E la mi inclusive; and this is the first hexachord of hard . The second hexachord is from the ut of C fa ut through to the la of high A la mi re inclusive; and this is the first natural hexachord. The third hexachord is from the ut of low F fa ut through to the la of D la sol re inclusive; and this is the first hexachord of soft . The fourth hexachord is from the ut of low G sol re ut through to the la of high E la mi inclusive; and this is the second hexachord of hard . The fifth hexachord is from the ut of C sol fa ut through to the la of highest a la mi re; and this is the second natural hexachord. The sixth hexachord is from the ut of high F fa ut through to the la of D la sol inclusive; and this is the second hexachord of soft . The seventh hexachord is from the ut of high G sol re ut through to the la of e la inclusive; and this is the third hexachord of hard . As is shown here in the following diagram:

Furthermore, all those pitches that are grouped, as has been explained, into a hexachord through the property of hard are said to be sung 'through hard '; those grouped through the natural property are said to be sung 'through natural'; and those grouped through the property of soft are said to be sung 'through soft ', the root pitch names of every hexachord nevertheless conforming to their own proper positions, and the other five following on from the positions of these root notes. At this point, since in the preceding material I have dealt separately with positions, clefs, pitch names, properties, and hexachord groupings, so that we can have a comprehensive understanding of all of these together, we may define the positions of the hand in their correct order thus: ut is a line whose clef is and in which a single pitch name, that is to say ut, is sung through hard , starting from its own position. A re is a space whose clef is A and in which a single pitch name, that is to say re, is sung through hard , starting from the position ut. mi is a line whose clef is square and in which a single pitch name, that is to say [310] mi, is sung through hard , starting from the position ut. C fa ut is a space wholse clef is C and in which two pitch names, that is to say fa and ut, are sung: fa through hard , starting from the position ut, and ut through natural, starting from its own position. D sol re is a line whose clef is D and in which two pitch names, that is to say sol and re, are sung: sol through hard , starting from the position ut, and re through natural, starting from the position C fa ut. Low E la mi is a space whose clef is E and in which two pitch names, that is to say la and mi, are sung: la through hard , starting from the position ut, and mi through natural, starting from the position C fa ut. Low F fa ut is a line whose clef is F and in which two pitch names, that is to say fa and ut, are sung: fa through natural, starting from the position C fa ut, and ut through soft , starting from its own position. Low G sol re ut is a space whose clef is G and in which three pitch names, that is to say sol, re and ut, are sung: sol through natural, starting from the position C fa ut; re through soft , starting from the position low F fa ut; and ut through hard , starting from its own position. High A la mi re is a line whose clef is A and in which three pitch names, that is to say la, mi and re, are sung: la through natural, starting from the position C fa ut; mi through soft , starting from the position low F fa ut; and re through hard , starting from the position low G sol re ut. High fa mi is a space, one of whose clefs is round , the other square , and in which two pitch names, that is to say fa and mi, are sung: fa through soft , starting from the position low F fa ut, and mi through hard , starting from the position low G sol re ut. C sol fa ut is a line whose clef is C and in which three pitch names, that is to say sol, fa and ut, are sung: sol through soft , starting from the position low F fa ut; fa through hard , starting from the position low G sol re ut; and ut through natural, starting from its own position.

D la sol re is a space whose clef is D and in which three pitch names, that is to say la, sol and re, are sung: la through soft , starting from the position low F fa ut; sol through hard , starting from the position low G sol re ut; and re through natural, starting from the position C sol fa ut. High E la mi is a line whose clef is E and in which two pitch names, that is to say la and mi, are sung: la through hard , starting from the position low G sol re ut, and mi through natural, starting from the position C sol fa ut. High F fa ut is a space whose clef is F and in which two pitch names, that is to say fa and ut, are sung: fa through natural, starting from the position C sol fa ut, and ut through soft , starting from its own position. High G sol re ut is a line whose clef is G and in which three pitch names, that is to say sol, re and ut, are sung: sol through natural, starting from the position C sol fa ut; re through soft , starting from the position high F fa ut; and ut through hard , starting from its own position. Highest a la mi re is a space whose clef is a and in which three pitch names, that is to say la, mi and re, are sung: la through natural, starting from the position C sol fa ut; mi through soft , starting from the position high F fa ut; and re through hard , starting from the position high G sol re ut. Highest fa mi is a line, one of whose clefs is round , the other square , and in which two pitch names, that is to say fa and mi, are sung: fa through soft , starting from the position high F fa ut, and mi through hard , starting from the position high G sol re ut. c sol fa is a space whose clef is c and in which two pitch names, that is to say sol and fa, are sung: sol through soft , starting from the position high F fa ut, and fa through hard , starting from the position high G sol re ut. d la sol is a line whose clef is d and in which two pitch names, that is to say la and sol, are sung: la through soft , starting from the position high F fa ut, and sol through hard , starting from the position high G sol re ut. e la is a space whose clef is e and in which a single pitch name, that is to say la, is sung through hard , starting from the position high G sol re ut. Chapter 7: On mutations With respect to the sixth topic: mutation is the changing of one pitch name into another. All pitch names, moreover, are mutable, but some more so, others less: Ut, then, is mutated into three other pitch names, that is to say into re, fa and sol. Re into four others, that is to say into ut, mi, sol and la. Mi into two others, that is to say re and la. Fa into two others, that is to say ut and sol. Sol into four others, that is to say ut, re, fa and la. La into three others, that is to say re, mi and sol.

As is clear, therefore, to an attentive observer, there are eighteen universally applicable mutations, namely utre, utfa, utsol; reut, remi, resol, rela; mire, mila; faut, fasol; solut, solre, solfa, solla; lare, lami, and lasol. Of the eighteen mutations, nine take place in order to ascend from one property into another, and nine in order to descend from one property into another. Whence the verses:

To ascend 'Utre, reut, remi with mire, and faut and solut, And solre, lare, lami enable you to rise.' To descend: Utfa, utsol, resol with rela, and mila, fasol, And solfa, solla, lasol head for the bottom when you sing.' Furthermore, every ascent takes place either from hard to natural, or from natural to soft , or from natural to hard , or from soft to hard , or from hard to soft , or from soft to natural. And every descent takes place either from natural to hard , or from soft to natural, or from hard to natural, or from hard to soft , or from soft to hard , or from natural to soft . And although, as I have said above, there are only eighteen universally applicable mutations, nevertheless, because all of the pitch names and hexachords of our hand (albeit some more than others) are repeated, on account of the large number of positions, there are fifty-two mutations in all found in this hand of ours: Two on C fa ut, which is the first position of mutation, namely faut and utfa: faut to ascend from hard to natural; and utfa to descend from natural to hard , as here: as here: Example 1:

Two on D sol re, namely solre and resol: sol-re to ascend from hard to natural; and resol to descend from natural to hard , as here: Example 2:

Two on low E la mi, namely lami and mila: lami to ascend from hard to natural; and mila to descend from natural to hard , as here: Example 3:

Two on low F fa ut, namely faut and utfa: fa-ut to ascend from natural to soft ; and utfa to descend from soft to natural, as here: Example 4:

Six on low G sol re ut, namely solre and resol; solut, utsol; reut, utre: solre to ascend from natural to soft ; resol to descend from soft to natural; solut to ascend from natural to hard ; utsol to descend from hard to natural; reut to ascend from soft to hard ; and utre to ascend from hard to soft , as here: Example 5:

Six on high A la mi re, namely lami, mila; lare, rela; mire and remi: lami to ascend from natural to soft ; mila to descend from soft to natural; lare to ascend from natural to hard ; rela to descend from hard to natural; mire to ascend from soft to hard ; and re mi to ascend from hard to soft , as is shown here: Example 6:

Six on C sol fa ut, namely solfa, fasol; solut, utsol; faut, utfa: solfa to descend from soft to hard ; fasol to descend from hard to soft ; solut to ascend from soft to natural; utsol to descend from natural to soft ; faut to ascend from hard to natural; and utfa to descend from natural to hard , as is shown here: Example 7:

Six on D la sol re, namely lasol, solla; lare, rela; solre et resol: lasol to descend from soft to hard ; solla to descend from hard to soft ; lare to ascend from soft to natural; rela to descend from natural to soft ; solre to ascend from hard to natural; and resol to descend from natural to hard , as here: Example 8:

Two on high E la mi, just like low E la mi, namely lami and mila: la-mi to ascend from hard to natural; and mila to descend from natural to hard , as here: Example 9:

Two on high F fa ut, just like low F fa ut, namely faut and utfa: faut to ascend from natural to soft ; and utfa to descend from soft to natural, as is shown here: Example 10:

Six on high G sol re ut, just like low G sol re ut, namely solre, resol; solut, utsol; reut, ut re: solre to ascend from natural to soft ; resol to descend from soft to natural; solut to ascend from natural to hard ; utsol to descend from hard to natural; reut to ascend from soft to hard ; and utre to ascend from hard to soft , as is shown here: Example 11:

Six on highest a la mi re, just like high A la mi re, namely lami, mila; lare, rela; mire, re mi: lami to ascend from natural to soft ; mila to descend from soft to natural; lare to ascend from natural to hard ; rela to descend from hard to natural; mire to ascend from soft to hard ; and remi to ascend from hard to soft , as is shown here: Example 12:

Two on c sol fa, namely solfa and fasol: solfa to descend from soft to hard ; and fasol to descend from hard to soft , as is shown here: Example 13:

Two on d la sol, namely lasol and solla: lasol to descend from soft to hard ; and solla to descend from hard to soft , as is shown here: Example 14:

On ut, A re, mi, and e la, however, no mutation takes place, because in each of these positions there is only a single pitch name; but where there is only a single pitch name no mutation can occur, since where all mutation is to take place two pitch names are required, that is to say one which is mutated and the other which is taken up through the process of mutation itself. In addition, no mutation takes place on high and highest fa mi, because mutation has necessarily to occur between two pitch names coinciding on a unison: that is to say, that the pitch name which is mutated and the other which is taken up through the process of mutation itself must be of one and the same sound, such as the fa and ut of C fa ut, or the sol and re of D sol re, and so on. Hence, since fa and mi are never of one and the same sound in any position at all, but rather they stand at a distance of a major semitone from one another, it is impossible for either to be mutated into the other. Nor should I neglect to mention that mutations were invented to account for the movement across from one property to another. Hence, after we have entered one particular property, we must never mutate before its last available pitch name; and so we understand by this that mutation should occur as rarely and as late as possible.

Again, mutation on any note does not alter its sound, but only its name. Hence, when we solmize, we mutate only because at that particular time we are performing the notes by name, for solmization is indeed the sung performance of notes by means of their names. From the foregoing, so that we can understand comprehensively the function of each mutation, let us define them in their correct order as follows: Utre is the mutation that takes place in both positions of G sol re ut in order to ascend from hard to soft . Utfa is the mutation that takes place on C fa ut and C sol fa ut in order to descend from natural to hard , and in both positions of F fa ut in order to descend from soft to natural. Utsol is the mutation that takes place in both positions of G sol re ut in order to descend from hard to natural, and on C sol fa ut in order to descend from natural to soft . Reut is the mutation that takes place in both positions of G sol re ut in order to ascend from soft to hard . Remi is the mutation that takes place in both positions of A la mi re in order to ascend from hard to soft . Resol is the mutation that takes place on D sol re and D la sol re in order to descend from natural to hard , and in both positions of G sol re ut in order to descend from soft to natural. Rela is the mutation that takes place in both positions of A la mi re in order to descend from hard to natural, and on D la sol re in order to descend from natural to soft . Mire is the mutation that takes place in both positions of A la mi re in order to ascend from soft to hard . Mila is the mutation that takes place in both positions of E la mi in order to descend from natural to hard , and in both positions of A la mi re in order to descend from soft to natural. Faut is the mutation that takes place on C fa ut and C sol fa ut in order to ascend from hard to natural, and in both positions of F fa ut in order to ascend from natural to soft . Fasol is the mutation that takes place on C sol fa ut and on c sol fa in order to descend from hard to soft . Solut is the mutation that takes place in both positions of G sol re ut in order to ascend from natural to hard , and on C sol fa ut in order to ascend from soft to natural. Solre is the mutation that takes place on D sol re and D la sol re in order to ascend from hard to natural, and in both positions of G sol re ut in order to ascend from natural to soft .

Solfa is the mutation that takes place on C sol fa ut and c sol fa in order to descend from soft to hard . Solla is the mutation that takes place on D la sol re and d la sol in order to descend from hard to soft . Lare is the mutation that takes place in both positions of A la mi re in order to ascend from natural to hard , and on D la sol re in order to ascend from soft to natural. Lami is the mutation that takes place in both positions of E la mi in order to ascend from hard to natural, and in both positions of A la mi re in order to ascend from natural to soft . Lasol is the mutation that takes place on D la sol re and on d la sol in order to descend from soft to hard . Finally, it should be noted that in the layout of these mutations a certain divine pattern is held, which can be grasped most easily by means of the following diagram:

Chapter 8: On intervals With respect to the seventh topic: an interval is the joining of one note to the next, with nothing else in between. Moreover, every interval can be made by arsis, that is to say through ascent, or by thesis, that is to say through descent. From this, it should be known that in each hexachord there are fifteen intervals, which can be produced ascending or descending, namely: four tones, one minor semitone, two dytones [major thirds], two semidytones [minor thirds], three diatessarons [perfect fourths], two diapentes [perfect fifths], and one diapente plus tone [major sixth], as is shown here: Example 15:

At this point, so that the essential qualities of these intervals may be grasped, they may be defined in their correct order as follows: The tone is the interval formed from the span of two minor semitones plus one comma: of this type are utre, reut; remi, mire; fasol, solfa; solla and lasol. The minor semitone is the interval formed from the span of two diaschismata: of this type are mifa and fami; and it is called a semitone from 'semus, -a, -um', that is to say 'imperfect', and from the noun 'tone', as is were an imperfect tone. And the word 'minor' is added to differentiate it from the major semitone, which is composed of two diaschismata and one comma. The dytone [major third] is the interval formed from the span of two tones: of this type are ut mi, miut; fala and lafa; and it is called a dytone from 'dy' with Greek 'y', which is 'two', and 'tone', as it were an interval composed of two tones. The diatessaron [perfect fourth] is the interval formed from the span of a tone and a semidytone [major third], or vice versa: of this type are utfa, faut; resol, solre; mila and lami; and it is called a diatessaron from 'dia' with Latin 'i', which is 'through', and 'tessaron', which is 'four', as it were an interval made up of four, because it takes up four positions.

The diapente [perfect fifth] is the interval formed from the span of a diatessaron [perfect fourth] plus a tone, or else a tritone and a semitone; of this type of utsol, solut; rela, lare; mimi and fafa both through ascent and descent. The notes, however, of each of these last two species of diapente, namely mimi and fafa, whether through ascent or descent, can never occur in one and the same hexachord. Hence they necessarily belong to different properties, as here:

And it is called a diapente from 'dia' with Latin 'i', which is 'through', and 'pente', which is 'five', as it were an interval made up of five, because it takes up five positions. The diapente plus tone [major sixth] is the interval formed from the span of a diapente plus a tone: of this type are utla and laut; and it is called a diapente plus tone because in this interval a diapente is placed along with a tone. There are, indeed, many other genera and yet more species of interval to be found in our hand, which are explained in the greatest detail, along with those described here, in my Speculum musices. But since these hold not inconsiderable difficulty, and since it has been my wish here to proceed with ease, I would refer readers desiring to know about them to this same Speculum. Chapter 9: Conclusion of the work Finally, then, may this exposition of the hand be sufficient for the needs of young men. I, Tinctoris, would strongly urge them to study it most earnestly, as being the very foundation of music. For, as all the best reasoning teaches us: where there is no foundation, there no building can be done above; and the result of this is that without a proper knowledge of the hand nobody can emerge outstanding in this art of music.

You might also like

- The Italian Cantata in Vienna: Entertainment in the Age of AbsolutismFrom EverandThe Italian Cantata in Vienna: Entertainment in the Age of AbsolutismNo ratings yet

- The Standard Cantatas Their Stories, Their Music, and Their ComposersFrom EverandThe Standard Cantatas Their Stories, Their Music, and Their ComposersNo ratings yet

- Serial Music: A Classified Bibliography of Writings on Twelve-Tone and Electronic MusicFrom EverandSerial Music: A Classified Bibliography of Writings on Twelve-Tone and Electronic MusicNo ratings yet

- The Influence of the Organ in History: Inaugural Lecture of the Department of the Organ in the College of Music of Boston UniversityFrom EverandThe Influence of the Organ in History: Inaugural Lecture of the Department of the Organ in the College of Music of Boston UniversityNo ratings yet

- Enigma Variations and Pomp and Circumstance Marches in Full ScoreFrom EverandEnigma Variations and Pomp and Circumstance Marches in Full ScoreNo ratings yet

- 4-Handed 05 PDFDocument29 pages4-Handed 05 PDF2712760No ratings yet

- Philippe de Vitry's Ars Nova Translation ExplainedDocument21 pagesPhilippe de Vitry's Ars Nova Translation ExplainedTomCafez100% (1)

- The Wound Dresser - A Series of Letters Written from the Hospitals in Washington During the War of the RebellionFrom EverandThe Wound Dresser - A Series of Letters Written from the Hospitals in Washington During the War of the RebellionNo ratings yet

- A Practical Guide To Musica Ficta - With Examples From The Works of Pierre de La Rue WILLIAM KEMPSTERDocument92 pagesA Practical Guide To Musica Ficta - With Examples From The Works of Pierre de La Rue WILLIAM KEMPSTERWilliam Kempster100% (1)

- Voice in Motion: Staging Gender, Shaping Sound in Early Modern EnglandFrom EverandVoice in Motion: Staging Gender, Shaping Sound in Early Modern EnglandNo ratings yet

- Composing Imitative Counterpoint Around PDFDocument59 pagesComposing Imitative Counterpoint Around PDFYuri Baer100% (1)

- The Musical Form of The Madrigal DentDocument12 pagesThe Musical Form of The Madrigal DentAlessandra Rossi100% (1)

- Theology of Wagner’s Ring Cycle I: The Genesis and Development of the Tetralogy and the Appropriation of Sources, Artists, Philosophers, and TheologiansFrom EverandTheology of Wagner’s Ring Cycle I: The Genesis and Development of the Tetralogy and the Appropriation of Sources, Artists, Philosophers, and TheologiansNo ratings yet

- Ziehn Manual - of - HarmonyDocument129 pagesZiehn Manual - of - HarmonybbobNo ratings yet

- A Proper Definition for the Earliest Adiastematic Notations of Gregorian ChantFrom EverandA Proper Definition for the Earliest Adiastematic Notations of Gregorian ChantRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Zarlino, The Senario, and TonalityDocument16 pagesZarlino, The Senario, and TonalityRodrigo S Batalha100% (1)

- Schoenber Vagrant Harmonies PDFDocument5 pagesSchoenber Vagrant Harmonies PDFerbariumNo ratings yet

- The Diminutions On Composition and TheoryDocument31 pagesThe Diminutions On Composition and TheoryMarcelo Cazarotto Brombilla100% (2)

- The Art of The Unmeasured Prelude For Harpsichord: France 1660-1720Document4 pagesThe Art of The Unmeasured Prelude For Harpsichord: France 1660-1720CarloV.ArrudaNo ratings yet

- Discant, Counterpoint, and HarmonyDocument22 pagesDiscant, Counterpoint, and Harmonytunca_olcayto100% (2)

- From Modality to Tonality: The Reformulation of Harmony and Structure in 17th-Century MusicDocument46 pagesFrom Modality to Tonality: The Reformulation of Harmony and Structure in 17th-Century MusicNuti Dumitriu100% (2)

- Alessandrini - Seconda Prattica MadrigalDocument9 pagesAlessandrini - Seconda Prattica MadrigalViviane Kubo100% (1)

- Vincent D'indyDocument23 pagesVincent D'indyPaul Franklin Huanca AparicioNo ratings yet

- Conrad - Von - Zabern-De Modo Bene Cantandi PDFDocument13 pagesConrad - Von - Zabern-De Modo Bene Cantandi PDFSandrah Silvio100% (1)

- Transformations in Music Theory and MusiDocument13 pagesTransformations in Music Theory and MusiAntonio Peña FernándezNo ratings yet

- A Source of Pasquini Partimenti in NapleDocument13 pagesA Source of Pasquini Partimenti in NapleRoy VergesNo ratings yet

- Thomas Ades ProjectDocument5 pagesThomas Ades ProjectJoseph CharlesNo ratings yet

- Berger - MODELS FOR COMPOSITION IN THE FOURTEENTH AND FIFTEENTH CENTURIES PDFDocument22 pagesBerger - MODELS FOR COMPOSITION IN THE FOURTEENTH AND FIFTEENTH CENTURIES PDFsantimusic100% (1)

- A New Look at Ars Subtilior Notation and Style in Codex Chantilly P. 74Document74 pagesA New Look at Ars Subtilior Notation and Style in Codex Chantilly P. 74Marco LombardiNo ratings yet

- On Compositional Process in The Fifteenth Century PDFDocument76 pagesOn Compositional Process in The Fifteenth Century PDFFlávio Lima100% (1)

- AbondanteDocument2 pagesAbondantePaulaRiveroNo ratings yet

- Morley's Rule For First-Species CanonDocument8 pagesMorley's Rule For First-Species CanonFederico100% (1)

- University of California Press American Musicological SocietyDocument22 pagesUniversity of California Press American Musicological Societykonga12345100% (1)

- Lasocki - Flute and Recorder in Combination (R&M-9-1974)Document5 pagesLasocki - Flute and Recorder in Combination (R&M-9-1974)Pedro Martin Salguero DuranNo ratings yet

- Bach Fugas AnaliseDocument52 pagesBach Fugas AnaliseAntonio Carlos100% (1)

- Tchaikovsky Priroda I Lyubov' (Natura e Amore) - SPARTITODocument24 pagesTchaikovsky Priroda I Lyubov' (Natura e Amore) - SPARTITOValentina EscobarNo ratings yet

- Baroque MusicDocument32 pagesBaroque MusicFonzy GarciaNo ratings yet

- Some Notes On Daphnis Et ChloéDocument13 pagesSome Notes On Daphnis Et ChloéetiennefleckNo ratings yet

- 'Esquisse de L'historie de L'HDocument251 pages'Esquisse de L'historie de L'HCleiton Xavier100% (1)

- Krenek's Conversions: Austrian Nationalism, Political Catholicism, and Twelve-Tone CompositionDocument74 pagesKrenek's Conversions: Austrian Nationalism, Political Catholicism, and Twelve-Tone Compositionthomas.patteson6837100% (1)

- A. C. Crombie - The History of Science From Augustine To GalileoDocument533 pagesA. C. Crombie - The History of Science From Augustine To GalileoDaniel Pereira Volpato100% (3)

- Leo Straus - What's Liberal EducationDocument19 pagesLeo Straus - What's Liberal EducationDaniel Pereira VolpatoNo ratings yet

- Anthony T. Kronman - Education's End - Why Our Colleges and Universities Have Given Up On The Meaning of LifeDocument321 pagesAnthony T. Kronman - Education's End - Why Our Colleges and Universities Have Given Up On The Meaning of LifeDaniel Pereira Volpato100% (3)

- Television and DivorceDocument17 pagesTelevision and DivorceHugoSantosdeMariaNo ratings yet

- Knapsack ProblemsDocument306 pagesKnapsack Problemsiamforum100% (3)

- Guide To Pronouncing Liturgical Latin (From Parish Book of Chant)Document2 pagesGuide To Pronouncing Liturgical Latin (From Parish Book of Chant)Daniel Pereira VolpatoNo ratings yet

- Liturgy and Church Music - Card Joseph Ratzinger, 1985Document12 pagesLiturgy and Church Music - Card Joseph Ratzinger, 1985Daniel Pereira Volpato100% (2)

- Stodder y Palkovich. 2012. The Bioarchaeology of IndividualsDocument305 pagesStodder y Palkovich. 2012. The Bioarchaeology of IndividualsLucia Curbelo100% (2)

- Backpack Starter - Achievement Test - Unit 4Document4 pagesBackpack Starter - Achievement Test - Unit 4zelindaaNo ratings yet

- Poetry and History - Bengali Ma?gal-K?bya and Social Change in Pre PDFDocument583 pagesPoetry and History - Bengali Ma?gal-K?bya and Social Change in Pre PDFChitralekha NairNo ratings yet

- Modern DramatistsDocument10 pagesModern DramatistsiramNo ratings yet

- I'll Face Myself (Persona 4) PDFDocument2 pagesI'll Face Myself (Persona 4) PDFLkz DibNo ratings yet

- Islamic Calendar 2014Document12 pagesIslamic Calendar 2014Dewi Nur JuliawatiNo ratings yet

- 16 Tricks: To Practice Your PronunciationDocument8 pages16 Tricks: To Practice Your PronunciationSteven BrianNo ratings yet

- Clue ScriptDocument11 pagesClue Scriptapi-296931788No ratings yet

- Text For AisaDocument252 pagesText For AisacolaNo ratings yet

- Periodic Law LabDocument2 pagesPeriodic Law LabHarrison Lee80% (5)

- DanceDocument4 pagesDanceRoiland Atienza BaybayonNo ratings yet

- Literary Movements: ..:: Syllabus 6 Semester::.Document4 pagesLiterary Movements: ..:: Syllabus 6 Semester::.FARRUKH BASHEERNo ratings yet

- Dua Lipa - Physical LyricsDocument2 pagesDua Lipa - Physical LyricsCarolina Jaramillo0% (2)

- The Historical Development of TrademarksDocument3 pagesThe Historical Development of Trademarksmarikit.marit100% (1)

- Snow White Play ScriptDocument9 pagesSnow White Play Scriptlitaford167% (3)

- Moist Chocolate Cake Recipe - FoodessDocument2 pagesMoist Chocolate Cake Recipe - FoodessjulieNo ratings yet

- Workman 2011 Children's CatalogDocument45 pagesWorkman 2011 Children's CatalogWorkman Extras0% (1)

- 1 Timothy 213-15 in The LightDocument390 pages1 Timothy 213-15 in The Light321876No ratings yet

- AP Concentration ProposalDocument2 pagesAP Concentration ProposalannagguilesNo ratings yet

- Panitia Bahasa Inggeris: Program Peningkatan Prestasi AkademikDocument53 pagesPanitia Bahasa Inggeris: Program Peningkatan Prestasi AkademikPriya MokanaNo ratings yet

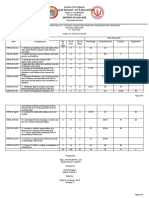

- Department of Education: District of San JoseDocument2 pagesDepartment of Education: District of San JoseJohnRudolfLoriaNo ratings yet

- Jihad al-Nafs: Spiritual StrivingDocument3 pagesJihad al-Nafs: Spiritual StrivingMansurNo ratings yet

- First Cut Off List of Ete-Govt Diets, On 25/06/2010Document42 pagesFirst Cut Off List of Ete-Govt Diets, On 25/06/2010chetanprakashsharmaNo ratings yet

- Twisted Sisters Knit SweatersDocument16 pagesTwisted Sisters Knit SweatersInterweave55% (62)

- Media in Animal FarmDocument6 pagesMedia in Animal Farmredrose_W249394No ratings yet

- Workshop 1 Personal InformationDocument7 pagesWorkshop 1 Personal InformationConeNo ratings yet

- Kunci Gitar Slank - Ku Tak BisaDocument6 pagesKunci Gitar Slank - Ku Tak BisaWilliamRayCassidyNo ratings yet

- Proof of Tawheed and Its Types From Quranic AyatsDocument9 pagesProof of Tawheed and Its Types From Quranic AyatsRana EhtshamNo ratings yet

- Power, Resistance, and Dress in Cultural ContextDocument2 pagesPower, Resistance, and Dress in Cultural ContextPriscillia MeloNo ratings yet

- Bruce Lee's Strength TrainingDocument4 pagesBruce Lee's Strength TrainingSoke1100% (1)