Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Economic Duress

Uploaded by

Joseph PhillipsOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Economic Duress

Uploaded by

Joseph PhillipsCopyright:

Available Formats

y session topic was the doctrine of economic duress in todays business and commercial contracts, and how it has

been applied in various jurisdictions. Duress is the inducement of a transaction in which one party exercises a degree of illegal domination on the other, to obtain and derive undue benefits. The earliest form of legally recognised duress is duress to the person. On this, the ruling authority is a 1973 Privy Council decision, in which a land deal was induced following murder threats to the victims family members. The progression to duress of goods is inevitablewhere the party in possession does not release the goods and arm-twists the owner to agree to his terms. The essence of the detention has to be illegitimate, there being various forms of lawful detention. Complexities in commercial transactions have led to the emergence of the concept of economic duress as a separate doctrinethat illegal pressure can be brought to bear on a party, without actually holding a gun to his head. Certain laws, such as anti-trust and consumer protection, have been strengthened to protect vulnerable parties. That apart, courts are also setting aside contracts vitiated by unlawful pressure. The problem lies in distinguishing between unacceptable commercial pressure, from the ordinary rough and tumble of the marketplace. The concept of duress finds place in the Indian Contract Act, 1872. Defined in Section 15, it recognises the concept of duress to goods as well, though its languages indicate limitation to criminal acts forbidden under the Indian Penal Code. Section 72 is more relevant to economic duress, providing that no person shall unjustly enrich himself at the expense of the other, and recognising the relief for restitution, where such enrichment is the consequence of coercion. The question is if Section 72 is subordinated to 15, and to what effect? The Privy Council, in Kanhaiya Lal vs National Bank of India, held that the term coercion used in Section 72, is not controlled by the Section 15 definition and must be used in its general and ordinary sense. Further decisions of the Indian courts have provided parameters for determination of economic duress e.g. actual or threatened pressure against which the victim registers protest. In pleading economic duress, a party must also have had no reasonable alternative to the action it seeks to set aside i.e., agreeing to the oppressive contract. If reasonable alternative was available, there cannot be any no choice situation. A person so threatened, therefore, can have the contract declared unenforceable for operative duress and also claim damages in a separate action for tort. Certain Commonwealth jurisdictions like the UK, Australia and Singapore have been pro-active in applying the doctrine to commercial contracts. Civil law countries have been more cautious and subjective in this regard, where the concern is on the impact the duress would have in vitiating the contract terms. Courts here have applied the doctrine sparingly, and more in relation to employee related contracts, or patently unequal non-compete and similar restrictive covenants. The reason perhaps is that in Indias liberalised business and legal environment, the courts perceive difficulty in defining inequality on a holistic analysis, without appearing to be jingoistic and biased. Indian courts are, perhaps, trying to undo the judicial activism of the 70s and 80s, in inevitably backing the underdog. There is a change in attitude in exercise of discretion. An example we often face in negotiating cross-border contracts are the dispute resolution, jurisdiction and governing law clauses being imposed unilaterally by the stronger party. The

other party takes its call based on commercial expediency. Is he entitled to challenge it later, on economic duress? Its safe to predict that Indian courts will decline such a plea. Courts these days are more inclined to enforce contracts, rather than setting them aside, to provide the stability and support the judiciary is required to.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Accounts HWDocument5 pagesAccounts HWDaniella AngellaNo ratings yet

- Spinning Mill ListDocument4 pagesSpinning Mill ListJigneshSaradava73% (15)

- Sarfaesi Act PPT-1Document21 pagesSarfaesi Act PPT-1Vironika Reddy100% (1)

- Reetu John Samuel PNQ-BLRDocument1 pageReetu John Samuel PNQ-BLRAjay KumarNo ratings yet

- Project ManagementDocument43 pagesProject ManagementAwot Haileslassie100% (3)

- Case 3C - Papa Gino'sDocument2 pagesCase 3C - Papa Gino'sPatrixia Nyah MifloresNo ratings yet

- Box Breakout System Trading ManualDocument11 pagesBox Breakout System Trading ManualAramaii TiNo ratings yet

- Process Costing Systems: Job vs Process CostingDocument10 pagesProcess Costing Systems: Job vs Process CostingMegan CruzNo ratings yet

- Hilton Chapter 4 Prerecorded LectureDocument12 pagesHilton Chapter 4 Prerecorded Lecturesunq hccnNo ratings yet

- Covid Relief For ContractorsDocument7 pagesCovid Relief For ContractorsGobinder Singh VirdeeNo ratings yet

- Derivatives Instruments... by Muhammad Al-Bashir M Al-AmineDocument45 pagesDerivatives Instruments... by Muhammad Al-Bashir M Al-Aminevishvasa11No ratings yet

- Overdue Account Payment Demand LetterDocument1 pageOverdue Account Payment Demand LetterKatherine OlidanNo ratings yet

- 3 từ còn lại:: I. NGỮ ÂM: (1 điểm) Chọn từ mà phần phần gạch chân có cách phát âm khác vớiDocument5 pages3 từ còn lại:: I. NGỮ ÂM: (1 điểm) Chọn từ mà phần phần gạch chân có cách phát âm khác vớiHương Quỳnh ĐặngNo ratings yet

- Invoice Progress Ke 3Document2 pagesInvoice Progress Ke 3rajaafif LcNo ratings yet

- Building An Effective Operator Interface For Complex Ethylene APC ApplicationsDocument14 pagesBuilding An Effective Operator Interface For Complex Ethylene APC ApplicationsAnil JosephNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 JonesDocument6 pagesChapter 6 JonesMaria ZakirNo ratings yet

- How To Pitch Your Business IdeaDocument1 pageHow To Pitch Your Business IdeaSulemanNo ratings yet

- INDICATORSDocument10 pagesINDICATORSadam.szafranskijdNo ratings yet

- Journal Entries Track Business TransactionsDocument20 pagesJournal Entries Track Business TransactionsTrishia Camille SatuitoNo ratings yet

- The 10 Types of Pricing StrategiesDocument9 pagesThe 10 Types of Pricing Strategieskhalid100% (1)

- Finacle Pre Bid QueriesDocument41 pagesFinacle Pre Bid Queriesanjali anjuNo ratings yet

- DOXDocument15 pagesDOXLynlou RabadonNo ratings yet

- Ethics in Public ServiceDocument28 pagesEthics in Public ServiceSarah Mae CatralNo ratings yet

- Managerial ACCT2 2nd Edition Sawyers Jackson Jenkins Solution ManualDocument24 pagesManagerial ACCT2 2nd Edition Sawyers Jackson Jenkins Solution Manualcharles100% (26)

- Bosch Common Rail Injector Valve CatalogDocument52 pagesBosch Common Rail Injector Valve CatalogSergioNo ratings yet

- Industrial Management Course at Addis Ababa UniversityDocument2 pagesIndustrial Management Course at Addis Ababa UniversityAman KemalNo ratings yet

- Mid-Term Question Paper Set - 1Document17 pagesMid-Term Question Paper Set - 1Archisha Srivastava0% (1)

- Acceptance Payment Form Estate Tax AmnestyDocument1 pageAcceptance Payment Form Estate Tax AmnestyAlvin III SiapianNo ratings yet

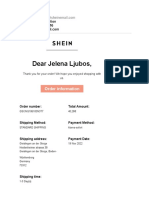

- Order ConfirmationDocument5 pagesOrder ConfirmationJelena KristoNo ratings yet

- International Student Exchange Programme Indicative Grade Point Average (iGPA) Fall 2021Document3 pagesInternational Student Exchange Programme Indicative Grade Point Average (iGPA) Fall 2021Koh Zi YangNo ratings yet