Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Comparative Analysis of The Yahwist and Priestly Traditions of The Creation Story

Uploaded by

Sandra AnnOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Comparative Analysis of The Yahwist and Priestly Traditions of The Creation Story

Uploaded by

Sandra AnnCopyright:

Available Formats

A Comparative Analysis of the Yahwist and Priestly Traditions of the Creation Story

Traditionally, Moses is considered to be the single source of the written form of the Pentateuch. However, the identification of inconsistencies in the Pentateuch renders the notion of a single source incredible. For example, the use of two distinct names, Yahweh and Elohim, for God which are used in Genesis and the repetition of the story of Abraham telling a foreign king that Sarah, his wife, was in fact his sister indicates that the contemporary form of the Pentateuch was compiled from multiple sources. Indeed, the ancient Israelite historian had a bias toward the retention of multiple sources, despite contradictions among sources, because the inclusion of several parallel stories was considered superior to providing merely one, less complete, account in which variations are reconciled (Boadt 79). Thus, the final editors of the Pentateuch have retained two unique accounts of the creation story, the Yahwist (J) account and the Priestly (P) account. The Yahwist and Priestly sources complement each other because each source achieves a variant purpose, as reflected by the conditions contemporary to their composition. The overriding historical theme relevant to the Yahwist account is that it was composed during the Davidic monarchy. Consequently, the J source seeks to glorify the monarchy and the land of Judah. In contrast, the P source was composed in the period after the Babylonian Exile, a trauma where God seemed to be absent. Therefore, the post-Exilic community required a more powerful, yet more impersonal God.

(Body Excised)

The Priestly and the Yahwist accounts of creation vary significantly. The Yahwist account was written during an age of optimism, strength and monarchy, and consequently allowed for a more personal relationship with God, an intimate relation evidenced by an apparently blessed Israel. The Priestly source, however, is written after Israel has endured much suffering, and consequently contains a God who is awesomely powerful, yet distinctly distant. The final editors, thus, have retained a story that relates both the magnificence of creation, and also the intimacy between God and his creation. Works Cited

Here is the order in the first (Genesis 1), the Priestly tradition:

Day 1: Sky, Earth, light Day 2: Water, both in ocean basins and above the sky(!) Day 3: Plants Day 4: Sun, Moon, stars (as calendrical and navigational aids) Day 5: Sea monsters (whales), fish, birds, land animals, creepy-crawlies (reptiles, insects, etc.) Day 6: Humans (apparently both sexes at the same time) Day 7: Nothing (the Gods took the first day off anyone ever did) Note that there are "days", "evenings", and "mornings" before the Sun was created. Here, the Deity is referred to as "Elohim", which is a plural, thus the literal translation, "the Gods". In this tale, the Gods seem satisfied with what they have done, saying after each step that "it was good". The second one (Genesis 2), the Yahwist tradition, goes: Earth and heavens (misty) Adam, the first man (on a desolate Earth) Plants Animals Eve, the first woman (from Adam's rib)

1. In the Beginning. The story of the people of Israel really begins with chapter 12 and the call to Abraham. The earlier chapters collect a variety of folk traditions about the beginning of things, bringing them into line with the religion of Israel as it had developed at the time of the writer. o 1.1 In the first chapter and the first few verses of the second, we have the "Priestly Code" source's account of creation. God here is the universal god that Israel had come to recognize by the time of the exile. 1.1.1 God's spirit moves over the water, as in Mesopotamian traditions, but the darkness of the deep is not his active opponent. 1.1.2 God puts "two great lights" in the sky--not named in the original as the Sun and Moon because these were objects of pagan worship. o 1.2 The second account of creation, in chapters 2 and 3, is from the Yahwist, writing in about 900 B.C. It is somewhat more primitive in conception. 1.2.1 God is an anthropomorphic being, walking in the garden. 1.2.2 Woman, created at the same time as man in Genesis 1.27 is seen in this account as a secondary creation. 1.2.3 Eating the apple from the tree threatens to make humanity god-like (v. 22). o 1.3 The story of Cain (chapter 4) assumes a developed civilization. Originally an account of the origin of the Kenites, a North Arabian tribe later associated with the Mt. Sinai revelation of Yahweh, it has been moved here by the Yahwist as a moral lesson. 1.3.1 It also begins the theme of the preference for younger sibling, carried through in many later stories (Isaac, Jacob, Rachel, Joseph, Solomon).

o o

1.4 The "Priestly" genealogy in chapter 5 is provided to connect the creation story of Chapter 1 with the story of the Flood. 1.5 The Flood story itself derives from Mesopotamian sources, though it is given a more moral twist here. Its aftermath, the following genealogies, and the story of the Tower of Babel (originally a Mesopotamian ziggarut) provide sources for the various peoples known to the Israelites. 1.5.1 The gigantic Nephilim mentioned in the opening verses of chapter 6 are legendary characters parallel to the Titans of Greek mythology.

2. Traditions of the Patriarchs. One major source of later Israelite tradition is the traditional notion of God as the patron deity of the tribe and its leader---the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, the God of Jacob. [The other major source, of course, is the devotion to Yahweh associated with the time in the desert and with the figure of Moses.] o 2.1 The God of Abraham. In the Yahwistic and later accounts, all of Israel is descended from Abraham and participates in his great Covenant with God [God's covenant with Noah included all humanity]. From a religious point of view, their view of Abraham is probably more important than any historical details. 2.1.1 Many historians, however, have doubted whether all of the later tribes of Israel were originally linked to the Abraham traditions. Some, in fact, have suggested that there was more than one Abraham. One seems especially connected with Haran in northern Mesopotamia. Another seems more connected with tribes on the Arabian penisula. Some have suggested that the name change in chapter 17 is somehow involved in reconciling separate traditions about originally separate figures. 2.1.2 Although later Israelite religion had a single center at Jerusalem, the Abraham traditions are associated with some other sites as well. Abraham, like the other patriarchs, is also pictured as being able to reconcile a devotion to his personal deity with acknowledging their identity with the Els worshipped in Canaan (though not the Baals). 2.1.2.1 Melchizedek, the priest-king of Salem (identified with Jerusalem) receives tithes from Abraham for El-Elyon (the God Most High) [14.20]. 2.1.2.2 In chapter 17, God reveals himself to Abraham as El Shaddai (either "God Almighty" or, likelier, "God of the Mountain"). 2.1.3 The Lot traditions (especially chapter 19, the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah) may have been originally unconnected with Abraham.

2.1.4 The story of Ishmael (chapter 21) establishes a relationship between Israel and the desert Arabs. 2.1.5 The story of the sacrifice of Isaac (chapter 22) expresses Israel's rejection of child-sacrifice as practiced by some of their neighbors. 2.2 The God of Isaac. Isaac is a much less developed figure, shown mainly as Abraham's son and Jacob's father, a connecting link, possibly artificial. Though he takes his wife from northern Mesopotamia, his traditions may come from southern tribes. 2.3 The God of Jacob. Jacob is the patriarch most directly connected with the later tribes. He is described as their father and his "blessing" on them in chapter 49 is a collection of oracles about their eventual role in Palestine. 2.3.1 But like his grandfather, Jacob points in at least two directions. He takes his bride in Haran, but he is the rival brother of Esau of the Edomites, a southern group. Like Abraham, he has a name change (to "Israel" in chapter 35). 2.3.2 Like Abraham, Jacob is connected with a variety of shrines and lives at piece with El figures. Traditions about Bethel and Schechem seem especially important.

You might also like

- The Pentateuch - Lesson 1 - TranscriptDocument27 pagesThe Pentateuch - Lesson 1 - TranscriptThird Millennium MinistriesNo ratings yet

- The Genre of The Book of Deuteronomy Is Not Much Different From That of ExodusDocument7 pagesThe Genre of The Book of Deuteronomy Is Not Much Different From That of ExodusSfs Major SeminaryNo ratings yet

- Apotheosis Sample Michael W FordDocument17 pagesApotheosis Sample Michael W FordRogério da silva santos63% (8)

- Canon of Hebrew ScriptureDocument6 pagesCanon of Hebrew ScriptureBassey AnthonyNo ratings yet

- Moral Teachings in CatholicDocument23 pagesMoral Teachings in CatholicBrenda Macanlalay AsuncionNo ratings yet

- DMin Thesis (Abstract)Document14 pagesDMin Thesis (Abstract)Eduardo MarinNo ratings yet

- Filipino DevotionsDocument6 pagesFilipino DevotionsMichelle100% (1)

- Sacraments - Historical Perspective (Reviewer)Document7 pagesSacraments - Historical Perspective (Reviewer)Wilhelm Bautista Boñon OPNo ratings yet

- Christian Family: God's Plan and Our MissionDocument8 pagesChristian Family: God's Plan and Our MissionLeo Mancera100% (1)

- Note On Introduction To Christian EthicsDocument75 pagesNote On Introduction To Christian EthicsJoseph Hyallamanyi Bitrus100% (1)

- Hermeneutics Reading Report 2Document12 pagesHermeneutics Reading Report 2Jessy SNo ratings yet

- Course Syllabus REL 103-God and Human LifeDocument15 pagesCourse Syllabus REL 103-God and Human LifeShardy Lyn Ruiz100% (1)

- The God Ninurta CHAPTER ONE Ninurtas RolDocument42 pagesThe God Ninurta CHAPTER ONE Ninurtas Rol葛学斌No ratings yet

- Holmes, M. (2006) - Polycarp of Smyrna, Letter To The Philippians. The Expository Times, 118 (2), 53-63Document11 pagesHolmes, M. (2006) - Polycarp of Smyrna, Letter To The Philippians. The Expository Times, 118 (2), 53-63Zdravko Jovanovic100% (1)

- CHS Term Paper - MosesDocument9 pagesCHS Term Paper - MosesAngel Barrachael GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Qigong ST PDFDocument5 pagesQigong ST PDFYasir KhalidNo ratings yet

- Topic 1 - Definitions of Terms Nature of Christian EthicsDocument35 pagesTopic 1 - Definitions of Terms Nature of Christian EthicsCHARMAINE JOY NATIVIDADNo ratings yet

- We Are Saved: To ServeDocument4 pagesWe Are Saved: To ServeDiocesan Catechetical Ministry Roman Catholic Diocese of Balanga100% (1)

- Dialogue and Proclamation (PONTIFICAL COUNCIL For INTERRELIGIOUS DIALOGUE)Document22 pagesDialogue and Proclamation (PONTIFICAL COUNCIL For INTERRELIGIOUS DIALOGUE)Calvin OhseyNo ratings yet

- Sacred ScriptureDocument85 pagesSacred ScriptureJan Paul Salud LugtuNo ratings yet

- 3.jacob Wrestles With God PSDocument4 pages3.jacob Wrestles With God PSshlm bNo ratings yet

- (NT3) Fulfillment in Luke-ActsDocument4 pages(NT3) Fulfillment in Luke-ActsparliamentNo ratings yet

- Bible Enthronement Booklet CebuanoDocument10 pagesBible Enthronement Booklet Cebuanothomas Hambre100% (1)

- Reed 204 Module 1 Topic 3 Liturgy LatestDocument16 pagesReed 204 Module 1 Topic 3 Liturgy LatestJudil BanastaoNo ratings yet

- 2021 Tagalog Rite For The Opening of Jubilee DoorDocument49 pages2021 Tagalog Rite For The Opening of Jubilee DoorAllen Jerome Abad100% (1)

- Theology Today SummaryDocument5 pagesTheology Today SummaryJeg GonzalesNo ratings yet

- English Collectio Part 2Document338 pagesEnglish Collectio Part 2Eryx CaritasNo ratings yet

- History THE REDEMPTORIST MISSIONARIES IN LIPA For Exhibit UsbDocument32 pagesHistory THE REDEMPTORIST MISSIONARIES IN LIPA For Exhibit UsbJrv SolomonNo ratings yet

- Priestly Formation in the Asian Context According to Pastores Dabo VobisDocument53 pagesPriestly Formation in the Asian Context According to Pastores Dabo VobisJudy MarciaNo ratings yet

- Ecclesia in AsiaDocument30 pagesEcclesia in Asiaapi-3834672100% (2)

- The disciples who started the organization of the Christian church were Saint Peter and Saint PaulDocument54 pagesThe disciples who started the organization of the Christian church were Saint Peter and Saint PaulAngelica Millare AndresNo ratings yet

- Abrahamic Religion: (Chapter 2)Document6 pagesAbrahamic Religion: (Chapter 2)Yhel LantionNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 The Nature of Translating PDFDocument21 pagesChapter 2 The Nature of Translating PDFpaulineNo ratings yet

- Ratio Institutionis (ENG) FINAL FEB 2020Document50 pagesRatio Institutionis (ENG) FINAL FEB 2020Carlos J. MedinaNo ratings yet

- Ethical Issues in MarriageDocument1 pageEthical Issues in MarriageJohn Marks SandersNo ratings yet

- Holy Rosary - Joyful MysteriesDocument43 pagesHoly Rosary - Joyful MysteriesRhea AvilaNo ratings yet

- Marialis CultusDocument40 pagesMarialis CultusGinoSDBNo ratings yet

- Divine Justice in Habakkuk and Today's InjusticesDocument5 pagesDivine Justice in Habakkuk and Today's InjusticesDaniel SolomonNo ratings yet

- PRAYER: “CALL” (AV PRESENTATIONDocument24 pagesPRAYER: “CALL” (AV PRESENTATIONHaziaaaakNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Bible Geography - AssignmentDocument24 pagesIntroduction To Bible Geography - AssignmentElias DefalgnNo ratings yet

- VIS Sacrifício LevíticoDocument371 pagesVIS Sacrifício Levíticopr_isaacNo ratings yet

- Biblical Theology of MissionDocument8 pagesBiblical Theology of MissionRin Kima100% (1)

- Vatican Document: Personae Humanae - A SummaryDocument3 pagesVatican Document: Personae Humanae - A SummaryGinoSDB88% (8)

- Mission and Identity of the Church: Proclaiming God's KingdomDocument12 pagesMission and Identity of the Church: Proclaiming God's KingdomMark Joshua RamiloNo ratings yet

- Online Teaching on Hope in Suffering and Joy in Liberation from the Book of JobDocument11 pagesOnline Teaching on Hope in Suffering and Joy in Liberation from the Book of JobECA100% (1)

- Lesson 5 Revelation NotesDocument13 pagesLesson 5 Revelation NotesRosemenjelNo ratings yet

- Structure and Hierarchy of the ChurchDocument5 pagesStructure and Hierarchy of the ChurchJunel SildoNo ratings yet

- Word Study On BaraDocument5 pagesWord Study On BaraspeliopoulosNo ratings yet

- Paul, An Advocate of The Ekklesial Space of EmancipationDocument7 pagesPaul, An Advocate of The Ekklesial Space of EmancipationJaison Kaduvakuzhiyil VargheseNo ratings yet

- Church SongsDocument27 pagesChurch SongsHeidi Joy JameroNo ratings yet

- RE 3: Liturgy and Sacraments ExplainedDocument5 pagesRE 3: Liturgy and Sacraments ExplainedRossele B. Cabe100% (1)

- Lay Ministers FormationDocument13 pagesLay Ministers FormationAlan de Guzman100% (1)

- The UST HymnDocument10 pagesThe UST HymnPatricia Ann CagampanNo ratings yet

- The Incarnation of The Word 2. Jesus Christ, True God and True ManDocument4 pagesThe Incarnation of The Word 2. Jesus Christ, True God and True ManMary Angelie CustodioNo ratings yet

- God's Unending LoveDocument2 pagesGod's Unending Lovemarc lauNo ratings yet

- Salvation HistoryDocument20 pagesSalvation HistoryReylito JumantocNo ratings yet

- Ash Wednesday: Welcome HypocritesDocument4 pagesAsh Wednesday: Welcome HypocritesPrincessAntonetteDeCastro0% (1)

- Basic OT NotesDocument20 pagesBasic OT NotesNimshiNo ratings yet

- Gal 4, 1-7 - FinalDocument22 pagesGal 4, 1-7 - FinalNathan Collins50% (2)

- Political and Social Context of Hosea's ProphecyDocument2 pagesPolitical and Social Context of Hosea's ProphecyjensmatNo ratings yet

- Galatians 5 1 6 ExegesisDocument18 pagesGalatians 5 1 6 ExegesisRichard Balili100% (1)

- The Historical Books: Old TestamentDocument23 pagesThe Historical Books: Old TestamentKathleen Anne LandarNo ratings yet

- “All Things to All Men”: (The Apostle Paul: 1 Corinthians 9: 19 – 23)From Everand“All Things to All Men”: (The Apostle Paul: 1 Corinthians 9: 19 – 23)No ratings yet

- hd2137 72 Irb Eng PDFDocument70 pageshd2137 72 Irb Eng PDFAzwani AbdullahNo ratings yet

- English Pesan Adven 2020Document2 pagesEnglish Pesan Adven 2020Sandra AnnNo ratings yet

- Recipe - Crumbliest SconesDocument2 pagesRecipe - Crumbliest SconesSandra AnnNo ratings yet

- BK 7 CHP 11 Lesson 8Document4 pagesBK 7 CHP 11 Lesson 8Sandra AnnNo ratings yet

- Instructions: Recipe IngredientDocument1 pageInstructions: Recipe IngredientSandra AnnNo ratings yet

- Understanding TeenagerDocument4 pagesUnderstanding TeenagerSandra AnnNo ratings yet

- How to Teach Values Through Everyday ChoicesDocument7 pagesHow to Teach Values Through Everyday ChoicesSandra AnnNo ratings yet

- Peanut Cookie - Fah Sang PengDocument1 pagePeanut Cookie - Fah Sang PengSandra AnnNo ratings yet

- Roast Lamb LegDocument2 pagesRoast Lamb LegSandra AnnNo ratings yet

- Roast Lamb LegDocument2 pagesRoast Lamb LegSandra AnnNo ratings yet

- Three Steps To Great Roast ChickenDocument5 pagesThree Steps To Great Roast ChickenSandra AnnNo ratings yet

- General Directory For Catechesis: Congregation For The ClergyDocument184 pagesGeneral Directory For Catechesis: Congregation For The ClergySandra AnnNo ratings yet

- Eucharist As Wedding Feas1Document4 pagesEucharist As Wedding Feas1Sandra AnnNo ratings yet

- Bread of LifeDocument11 pagesBread of LifeSandra AnnNo ratings yet

- Communion of The PeopleDocument6 pagesCommunion of The PeopleSandra AnnNo ratings yet

- ChildrenDocument4 pagesChildrenSandra AnnNo ratings yet

- Christmas Carols List2008Document1 pageChristmas Carols List2008Sandra AnnNo ratings yet

- Concerning Eucharistic AdorationDocument6 pagesConcerning Eucharistic AdorationSandra AnnNo ratings yet

- Not That FarDocument13 pagesNot That FarSandra AnnNo ratings yet

- Infant KingDocument32 pagesInfant KingSandra AnnNo ratings yet

- How the Eucharist Builds Community in the ChurchDocument4 pagesHow the Eucharist Builds Community in the ChurchSandra AnnNo ratings yet

- Christmas Carols ListDocument1 pageChristmas Carols ListSandra AnnNo ratings yet

- Christmas Carols List2008Document1 pageChristmas Carols List2008Sandra AnnNo ratings yet

- A Message For The Commemorative BookDocument3 pagesA Message For The Commemorative BookSandra AnnNo ratings yet

- Let's PartyDocument10 pagesLet's PartySandra AnnNo ratings yet

- Christmas Carols2008Document20 pagesChristmas Carols2008Sandra AnnNo ratings yet

- Christmas Carols List2010Document1 pageChristmas Carols List2010Sandra AnnNo ratings yet

- Roast Lamb LegDocument2 pagesRoast Lamb LegSandra AnnNo ratings yet

- Understanding Human Sexuality & the Catholic ChurchDocument13 pagesUnderstanding Human Sexuality & the Catholic ChurchSandra AnnNo ratings yet

- E. P. Garrison, Attitudes Toward Suicide in Ancient GreeceDocument35 pagesE. P. Garrison, Attitudes Toward Suicide in Ancient GreeceVicky GkougiaNo ratings yet

- Interview with Longtime Prosecutor Provides Insight and AdviceDocument3 pagesInterview with Longtime Prosecutor Provides Insight and AdvicearielramadaNo ratings yet

- From The Director's Desk: ActivitiesDocument4 pagesFrom The Director's Desk: ActivitiesVivekananda KendraNo ratings yet

- Yatharth Geeta: PrefaceDocument32 pagesYatharth Geeta: PrefacecaptstomarNo ratings yet

- 05 CouncccilDocument4 pages05 Councccilnils.pointudNo ratings yet

- Bixler V Scientology: Petition For RehearingDocument45 pagesBixler V Scientology: Petition For RehearingTony OrtegaNo ratings yet

- Safeguard Your Mind CA 2013 NotebookDocument34 pagesSafeguard Your Mind CA 2013 NotebookAutumn JJNo ratings yet

- Imam ShafiDocument6 pagesImam Shafim.salman732No ratings yet

- FOUR WONDERFUL OPPORTUNITIES TO ENCOUNTER GODDocument2 pagesFOUR WONDERFUL OPPORTUNITIES TO ENCOUNTER GODEthel Joy EstrabinioNo ratings yet

- Faiz Ul Bari Tarjuma Fathul Bari para 19,20,21Document905 pagesFaiz Ul Bari Tarjuma Fathul Bari para 19,20,21Islamic Reserch Center (IRC)No ratings yet

- Secret of AscendantsDocument3 pagesSecret of AscendantsReuben100% (1)

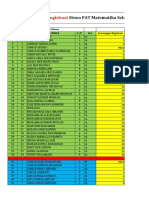

- Data Siswa PAT Matematika Selasa, 12 Mei 2020: RegistrasiDocument14 pagesData Siswa PAT Matematika Selasa, 12 Mei 2020: RegistrasiNakaila SadilaNo ratings yet

- A Paper Presenration On Urban MissionDocument6 pagesA Paper Presenration On Urban MissionSamson M SamsonNo ratings yet

- Haym Soloveitchik - A Response To Rabbi Ephraim Buckwold's Critique of 'Rabad of Posquieres A Programmatic Essay'Document49 pagesHaym Soloveitchik - A Response To Rabbi Ephraim Buckwold's Critique of 'Rabad of Posquieres A Programmatic Essay'danielpriceklyNo ratings yet

- Manuscript RepositoriesDocument71 pagesManuscript RepositoriesMayuri WayalNo ratings yet

- Prophet Muhammad's Life and TeachingsDocument7 pagesProphet Muhammad's Life and TeachingsBenish RehanNo ratings yet

- GN120 - 29th July 2018 - 17th & 18th Sunday in Ordinary TimeDocument2 pagesGN120 - 29th July 2018 - 17th & 18th Sunday in Ordinary TimewebmasterNo ratings yet

- Movie Reflection on Evan AlmightyDocument3 pagesMovie Reflection on Evan AlmightyTrinity DNo ratings yet

- God of Slaughter GlossaryDocument12 pagesGod of Slaughter Glossaryhanaffi1No ratings yet

- Dr. Subramanian Swamy Vs State of Tamil Nadu & Ors On 6 December, 2014Document20 pagesDr. Subramanian Swamy Vs State of Tamil Nadu & Ors On 6 December, 2014sreevarshaNo ratings yet

- Leadership and Church Growth - The Case of Chuck SmithDocument18 pagesLeadership and Church Growth - The Case of Chuck SmithMariana De ZumárragaNo ratings yet

- Islamic Socio AssignmentDocument6 pagesIslamic Socio AssignmentMaaz KhanNo ratings yet

- Greek and Roman MythologyDocument7 pagesGreek and Roman Mythologypaleoman8No ratings yet

- Lecture 2 Comparison With ReligionsDocument7 pagesLecture 2 Comparison With Religionsyaseen kharaniNo ratings yet

- The Panay Creation Myth of Tungkung Langit and AlunsinaDocument10 pagesThe Panay Creation Myth of Tungkung Langit and AlunsinaCheng BauzonNo ratings yet

- Understanding Morality Through MercyDocument39 pagesUnderstanding Morality Through MercyJohn Feil JimenezNo ratings yet

- Excerpt From - Hand Wash Cold - by Karen Maezen MillerDocument3 pagesExcerpt From - Hand Wash Cold - by Karen Maezen Millermypinklagoon8411No ratings yet