Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Singer WarStories

Uploaded by

Samuel Andrés AriasOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Singer WarStories

Uploaded by

Samuel Andrés AriasCopyright:

Available Formats

Qualitative Health Research http://qhr.sagepub.

com/

''War Stories'': AIDS Prevention and the Street Narratives of Drug Users

Merrill Singer, Glenn Scott, Scott Wilson, Delia Easton and Margaret Weeks Qual Health Res 2001 11: 589 DOI: 10.1177/104973201129119325 The online version of this article can be found at: http://qhr.sagepub.com/content/11/5/589

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Qualitative Health Research can be found at: Email Alerts: http://qhr.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://qhr.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://qhr.sagepub.com/content/11/5/589.refs.html

>> Version of Record - Sep 1, 2001 What is This?

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD DE ANTIOQUIA on July 31, 2013

QUALITATIVE Singer et al. / STREET HEALTH NARRATIVES RESEARCHOF / September DRUG USERS 2001

War Stories: AIDS Prevention and the Street Narratives of Drug Users

Merrill Singer Glenn Scott Scott Wilson Delia Easton Margaret Weeks

The day-to-day discourse of illicit drug users is replete with stylized narratives of street experience. These war stories, as they are popularly known, are shared among drug users as they hustle for money, purchase drugs, get high, and hang out in diverse street locations. Drug-user narratives, which describe complex adventures and grave suffering, are primary ethnographic sources of information about patterns of drug consumption and risk behaviors. Importantly, in the time of AIDS, street narratives provide a much-needed window on the generally hidden lives of socially marginalized street drug users. As part of an effort to put the analysis of drug-user war stories to use in HIV prevention, in this article the authors analyze a corpus of street narratives told to members of an HIV-prevention research team in Hartford, Connecticut.

parked especially by the AIDS epidemic and recognition of the significant role drug use plays in HIV transmission, a growing public health focus has developed around increasing our understanding of the lives and behaviors of street drug addicts, especially injection drug users and crack cocaine users. Both of these groups of illicit drug users are known to be at high risk for HIV infection (Jarlais et al., 1994; Kral, Bluthenthal, Booth, & Watters, 1998; Singer, 1999b; Sterk, 1999). Public health researchers have been concerned especially with finding ways to expand our awareness of the (a) precise nature of risk behaviors among drug users (i.e., specific acts that increase the chance that a drug user will be infected with HIV and/or transmit the virus to others), (b) social contexts that facilitate risk behavior, (c) social structural factors that contribute to risk taking, and (d) the role of social networks and relationships in promoting or inhibiting risky acts. However, conventional epidemiological approaches, such as community surveys and structured interviews, have important drawbacks in this arena of research (Bourgois, 1995). As a result, there has been a strong interest in identifying alternative approaches for gathering critical information needed in AIDS prevention in this population. Street drug users have been described as a hidden population, a group that resides outside of institutional, clinical, or easily accessible public settings and whose activities are clandestine and therefore concealed from the view of mainstream society and agencies of social control (Watters & Biernacki, 1989, p. 417).

QUALITATIVE HEALTH RESEARCH, Vol. 11 No. 5, September 2001 589-611 2001 Sage Publications

589

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD DE ANTIOQUIA on July 31, 2013

590

QUALITATIVE HEALTH RESEARCH / September 2001

Intentional concealment makes it difficult to reach street drug users with standard epidemiological data collection methods (Singer, 1999a). Although innovative street outreach techniques and snowball peer recruitment strategies have proved successful in penetrating some layers of the street drug-using population for survey research, other data collection problems remain (Broadhead et al., 1998; Coyle, Needle, & Normand, 1998). As indicated by Bourgois (1995),

By definition, individuals who have been marginalized socially, economically, and culturally have had negative long-term relationships with mainstream society. Most drug-users and dealers distrust representatives of mainstream society and will not reveal their intimate experiences of substance abuse or criminal activity to a stranger on a survey instrument, no matter how sensitive and friendly the interviewer may be. Consequently, most of the criminologists and sociologists who painstakingly undertake epidemiological surveys on crime and substance abuse collect fabrication. (p. 12)

As a result, ethnographywhich has the ability to elucidate information about highly private and often illicit behaviors from individuals who have learned to be distrustful of outsidershas gained an important role in AIDS-prevention research (Kotarba, 1990; Singer, 1992; Weeks, Singer, & Schensul, 1993). The remarkable new interest in ethnography and qualitative research (Altheide & Johnson, 1994, p. 485) stems from the types of relationships it encourages between respondents and researchers, the varied settings in which it is able to gather data on the behaviors and experiences of study participants, and the nature of the data it seeks to collect. As Bourgois (1995) argued, ethnography is better suited than exclusively quantitative methodologies for documenting the lives of people (p. 12) at risk because it is based on longer term, rapport-based connections with members of the target population, creates multiple opportunities for relaxed and casual conversations between researchers and research participants, and directs researchers to encourage the sharing of detailed narratives of daily living. The intended goal of ethnographyto gain an experience-near, contextembedded, and insider-oriented perspective on the issues or social groups under studyresults in the collection of extensive qualitative or textual data, including both field observations produced by the ethnographer and statements by participants made during informal conversations (with each other and/or with the ethnographer) or in specific response to researcher questions. As Spradley (1970) noted, ethnography in large part consists of continually listening to men [and women] talk about their experiences (p. 71) and recording these statements. Indeed, the appeal of ethnography in AIDS-prevention research is rooted in what Smith (1978) termed the quality of undeniability of detailed insider accounts. As Miles and Huberman (1984) stressed, Words, especially when they are organized into incidents or stories, have a concrete, vivid meaningful flavor that often proves far more convincing to a readeranother researcher, a policymaker, a practitionerthan pages of numbers (p. 15). Geertz (1973), in a well-cited passage about the nature of ethnographic data, asserted that what we call our data are really our own constructions of other peoples constructions of what they and their compatriots are up to (p. 9). In the course of field research with drug users, ethnographers hear many tales from their informants about the vagaries and challenges of life on the streets and life on drugs.

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD DE ANTIOQUIA on July 31, 2013

Singer et al. / STREET NARRATIVES OF DRUG USERS

591

Often involving complex adventures and grave suffering, the narratives told among drug users as they hustle for money, cop (find a dealer and purchase drugs), get high, and hang out are primary ethnographic sources of information about drug use and risk behavior. In addition to direct observation and the day-today conversational process among and with informants, they constitute much of the database collected by street drug ethnographers and outreach workers (Bourgois, 1995; Waterston, 1993). War stories, as these insider narratives of street experience are often called, both by tellers and their audiences, provide an important window on the generally hidden lives of socially marginalized street drug users. At the same time, from an epidemiological research perspective, Geertzs (1973) invocation of the notion of construction raises the issue of validity and consequently the utility of narrative ethnographic data in the development of effective, realitybased public health responses to threatening diseases such as HIV/AIDS and substance abuse. As Geertz observed, ethnographic data are fictions; fictions in the sense that they are something made, something fashioned (p. 15). Consider, for example, Kleinmans (1988) analysis of narrative construction among medical patients:

Patients order their experience of illnesswhat it means to them and to significant othersas personal narratives. The illness narrative is a story the patient tells . . . to give coherence to the distinctive events and long-term course of suffering. . . . The plot lines, core metaphors, and rhetorical devices that structure the illness narrative are drawn from cultural and personal models for arranging experiences in meaningful ways and for effectively communicating these meanings. (p. 49)

As this discussion implies, the content of stories is culturally and personally shaped to fill desired social and individual needs for the storyteller. How does this process of cultural construction affect our ability to treat drug users stories as useful data for public health programming? Although it is easy to become captivated by the stories of your informants (Maxwell, 1996, p. 14), to date, the issue of validity has received only limited attention in the ethnographic HIV-prevention literature on drug users (Fendrich, Mackesy-Amiti, Wislar, & Goldstein, 1995). However, many drug users stories we have heard during the course of street ethnographic research seem, at a minimum, to be embellished in light of our own direct experiences over the past decade with the street drug scene. Consequently, as we have listened to drug-user war stories, we sometimes have pondered whether they are invented from whole cloth or instead contain objective facts that are relevant to the assessment of AIDS risk and the development of AIDS prevention. In the end, we have come to the realization, expressed in this article, that the primary relevance of drug-user stories to AIDS prevention lies not in their ability to be read as objective and verifiable accounts of actual events but rather in their effectiveness in giving a meaningful voice to heartfelt and troubling sentiments and concerns. In this sense, drug-user narratives can serve as very useful windows on what might be the most important kinds of information needed for effective prevention. These points are illustrated using a corpus of stories of street events, adventures, and sufferings told to members of our research team in Hartford, Connecticut, by active drug users in the course of ethnographic conversations and qualitative interviews. Research team members include both anthropologists and

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD DE ANTIOQUIA on July 31, 2013

592

QUALITATIVE HEALTH RESEARCH / September 2001

anthropologically trained AIDS community outreach workers who have gained experience in conducting in-depth qualitative interviews. The team is multicultural and includes both male and female ethnographers and outreach workers. Data for the analysis presented in this article were collected primarily through the Study of High Risk Drug Use Settings for HIV Prevention supported by the National Institute on Mental Health and the National Institute on Drug Abuse.1 This study is designed to understand the nature of HIV risk in drug-use sites (e.g., abandoned buildings) and to assess the potential for implementing HIV interventions in such sites. In this ongoing project, 88 in-depth interviews have been conducted with 76 drug users, most of which were audiorecorded and transcribed for analysis. In other cases, narratives were recorded in the field notes of project ethnographers and outreach staff members. Tape-recorded interviews were conducted at the project offices (at two sites in Hartford), whereas field notes were recorded on the street or in drug-use locations (or immediately after visits to these locations). Although interviews were open ended, they were guided by a set of key research questions. Participants for these interviews were recruited through standard street outreach to known high-drug-use areas of the city (based on prior studies). Criteria for participant inclusion were active heroin or cocaine use (during the past 30 days), being at least 18 years of age, and able to give informed consent. Content analysis of these data by project staff members identified primary themes that could be used to order the narratives and to construct a typology of narratives. Here we present this typology and representative examples of the various narrative types and subtypes commonly found among drug users and use this information to suggest ways in which drug-user war stories can contribute to AIDSprevention efforts. Specifically, we call attention to the oppositional tension of drug users narratives and to three themes found in the narrativesgenerosity, betrayal, and efficacyin terms of their relevance for HIV prevention among drug users.

NARRATIVES IN ETHNOGRAPHIC RESEARCH

Telling stories is a central human social activity and hence a behavior and a social process of keen ethnographic interest (Bruner, 1986; Singer, Davison, & Gerdes, 1988). Following Mattingly (1998), we employ a fairly simple and straightforward definition of a narrative as a discourse featuring human adventures and sufferings connecting motives, acts, and consequences in causal chains (p. 275). In other words, as contrasted with other kinds of talk, a narrative is an account of a specific event or a set of linked events in which actors take specific actions with socially meaningful outcomes. Narratives have been analyzed in several ways, including seeing them as a primary mode by which people organize, display, and work through experiences (Rubinstein, 1995, p. 259). As Gee (1985) asserted, Probably the primary way human beings make sense of their experience is by casting it in narrative form (p. 11). The narrative, in short, is a mechanism people use to understand the social life around us (Carrithers, 1992, p. 78). In addition, a narrative affixes blame and assigns responsibility (Mattingly, 1998, p. 286) and in so doing affirms moral boundaries and suggests a course of action (Good & DelVecchio Good, 1994; Price, 1987). Narratives situate people in local moral worlds, constructing borders and pathways of valued and devalued conduct (Kleinman & Kleinman, 1991). Finally,

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD DE ANTIOQUIA on July 31, 2013

Singer et al. / STREET NARRATIVES OF DRUG USERS

593

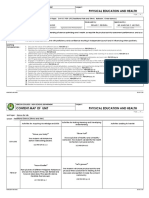

FIGURE 1:

Typology of Drug-User Narratives

narratives are interactive, uniting a speaker and his or her audience. A good storyteller is persuasive and seduces the audience into seeing the world in a particular way (Mattingly, 1998, p. 286). In other words, as a form of verbal performance and display (Tedlock, 1983), narration allows the storyteller to construct himself or herself, social others, and social events in useful and meaningful ways. As Keesing (1987) emphasized, All talk is contextually situated, socially implicated (p. 163). In a research setting, an informant narrative is one of the most important ways of communicating, This is who I am and what I do. In addition, however, as Cain (1991) showed in her analysis of narratives at Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, narratives are a means by which storytellers acquire and construct identities and self-understanding.

TYPOLOGY OF DRUG-USER NARRATIVES

Narratives, observed Cohan and Shires (1988), consist of events placed in a sequence to delineate a process of change (p. 52). Events depict activities of some sort, what Cohan and Shires referred to as occurrences in time (an action performed by or upon a human agent) or a state of existing in time (such as thinking, feeling, being or having) (p. 53). Rimmon-Kenan (1983), in a discussion of narrative analysis, noted that they may be decomposed into a series of mini-events and intermediary states, soconverselya vast number of events may be subsumed under a single event label (p. 15). In this light, in listening to numerous drug-user war stories over the past several years, we have come to see that they can be grouped into a number of distinct categories. Using etic event labels (i.e., designations developed by our researcher team), we have constructed a preliminary typology of drug-user stories as displayed in Figure 1. We do not view this typology as either comprehensive of all street drug users stories or even as the only means of ordering the specific stories in our data set but rather as an instrumental approach to organizing and evaluating a complex body of narrative material. We constructed this typology by twice reading through the interview transcripts and field notes and identifying distinct stories of personal experience as a drug user. We then reviewed

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD DE ANTIOQUIA on July 31, 2013

594

QUALITATIVE HEALTH RESEARCH / September 2001

the narratives to ascertain the key theme(s), message(s), or plot element(s) of each story (Reissman, 1993). Examination of these themes suggested a typological organization of primary, secondary, and tertiary categories. Any particular narrative may include more than one of the themes used to construct our categories. The typology consists of the following six primary thematic categories: learning the ropes, adventurous experiences, miraculous gains, not like the old days, the power of drugs, and suffering and regret. Each of these types and their inclusive subtypes will be examined in turn. Learning the ropes. This narrative type involves stories about acquiring the knowledge and skills needed to get and use drugs and to survive in the street subculture. For example, the following narrative told by Rodney,2 a middle-aged African American man, explained the important role women played for him in learning how to use crack cocaine:

Everything I learned about this shit, I learned from girls. Girls I was dealing with. Girls I was messing with. I learned everything by watching them. I learned how to cook [the cocaine], I learned how to smoke, I learned how to make pipes, all that shit, because I was watching the girls. Girls know better than anybody how to make pipes because they have the patience to sit there, take their time, and do it right. . . . Guys are like, Come on, I want to smoke! You know, shit leaking everywhere. Man you dont care, just put it in there, light it up. Girls are like, No, [dont] waste my stuff. Take your time. Get it right. Guys are . . . [and] I am the same way, put it in there man, light it, Ill pull it hard. . . . Girls dont want to hear that shit. Uh uh. I just tricked [prostituted] for this shit [drugs], you crazy!

Although we have not heard many narratives in which a woman teaches the drug-use ropes to a man, we have collected many in which a male partner, friend, or relative is the primary source of drug-scene knowledge for both women and men. In the following narrative, voiced by Tony, a 35-year-old man of mixed Puerto Rican and Italian background, specific instruction in both drug use and drug dealing was provided by his father:

From the time I was 6 or 7, he would take me with him to the bars where he would play pool and hang out and I would watch this man just come out playing pool like he was a shark, you know. And, my father, he used to say, Watch me, you know, learn, and by the time I was 12 years old, thats when everything started. I was drinking, you know, cause I was watching my father. . . . Thats when I started to drink and my father, he had me start working out there selling dope. I didnt start doing dope until about 13, thats when I asked him one day because I seen him doing it and decided [to ask]. And he shot me up at 13 and Ive been flying ever since. . . . I cant hate my father for anything that he did cause his father taught him the same thing. So, he was only teaching me what he knew best. He wanted me to be like him and I ended up being like him.

Adventurous experiences. The second kind of narrative in our typology includes several distinct subtypes, but all of these tales share a common theme involving the description of events or abilities that go beyond normal limits or routine occurrence. In addition, many of these narratives challenge expectations and common dominant society stereotypes about the lives of street drug users. For example, John, a long-term polydrug user, told the following story that exemplifies the wild party subtype:

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD DE ANTIOQUIA on July 31, 2013

Singer et al. / STREET NARRATIVES OF DRUG USERS

595

I used to pick up Barbara when I used to have my limousine parties. This is when I used to rent these big, long eight-wheel limos and have parties in em. It was like, hey I got at least one or two girls, no matter what the situation was. So, I would call on the phone and tell her to come to the front window . . . and I would be sitting there looking up at her through the window, one of the sun roofs of these super long stretches that I used to rent. And you can ask the fellows about this . . . I used to have some wild parties. Eddie would be one of the people who could tell you about that. He used to sit in the fucking limo and just get high and have parties with ounces [of drugs]. I was shooting [injecting drugs] and smoking, and I just felt powerful. Wed drive around and pick up people. Call em up and pull up in front of their houses and have limo parties.

Notable in this story is the contrast created between the events described and the usual harsh reality of most street drug users. Whereas personal situations vary, for many individuals caught up in a street-oriented, drug-centered life, reality consists of days spent engaged in petty hustles to raise small sums of money for the immediate purchase of drugs, nights spent in run-down abandoned buildings or walking the streets because there is no safe place to sleep, owning only meager personal possessionsand even these are routinely subject to being lost, confiscated, or stolen and having few if any markers of success and value in the wider society. By telling and retelling stories such as this one, however, there is an opportunity to claim possession of one of the flashier badges of success (driving around in a limousine). John also shared the following tale that is illustrative of the amazing street skill subtype of adventurous experience narratives. In this type of story, the teller calls attention to his or her ability to get by through the deft use of personal attributes, street knowledge, and peer networks:

[Over on] Baker Street, that was my spot. And if you hear people tell ya, theyll tell you that was my turf, my turf! As a matter of fact, Peter, the guy Im staying with right now, has run into a lot of people that know me from the old days and he is quite impressed. The moves I can make! We went out the other day with no money, no nothing and came home with . . . $5 worth of ready rock [crack cocaine] and a bag of dope [heroin]. And we [had] left the house with no money. Nothing, I mean flat broke! [Peter] was dope sick [beginning drug withdrawal], and we came home proper, and his mother wouldnt give him no money to get high, didnt want to give up no loot. . . . I ran into a dope dealer I know. He hit me off with a bag of dope [and] we managed to get $5 worth of coke with the change he scrounged [panhandled]. . . . Amazing sometimes! [And yesterday] I ran into Tom; Tom gave me 10 bucks. Ran into another older brother of his and his brother was cooking up some [drugs]. And he gave me 10 yesterday. That got me through yesterday!

Another example of this type of story was told to us by Tony:

Well, I got connections, see. I got connections with the Solids [Solidos, a Puerto Rican street gang]. . . . If I needed . . . if something happened to me, they would help me out, or I would help myself out. . . . I was affiliated with Twenty Love [a predominantly African American street gang]. Back then it was the Magnificent Twenties. . . . In jail and on the streets, Solids and Twenty Love are cousins. They watch each others back. . . . To tell you the truth, with the families [street gangs] in jail now its a little bit better than trying to be on your own. Cause, instead of one on one, youre gonna come full force. [Back in the day] I was running my block, it was five or six of us. I was vice president [of the gang]. And that means full serve, and there were captains, stuff like that. I tell who what [drugs] to sell. Nobody could sell on that block unless they were Twenties. . . . I had to decide who I could trust and

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD DE ANTIOQUIA on July 31, 2013

596

QUALITATIVE HEALTH RESEARCH / September 2001

who I couldnt. . . . We used to have one person that stayed at one end of the block and another at the other end, with walkie-talkies. And wed talk to each other to see who was coming, cops, whatever, and we used signals off of the porch. We would use 5-0 to signal for the police coming [from the TV program, Hawaii 5-0]. . . . I was smart. I know how to run it. Like if you had everybody out there selling dope [heroin], boom, boom boom . . . they get caught. But that is why I had runners, thats why I had guys at the end of the street. I can pay them $20, cause if you try to be greedy and keep all the money for yourself you gonna get caught faster. See, I learned from my father in Philadelphia. He used to have the same thing, guys down at the end of the street looking out, using hand signals. I applied what I learned from him to my business and it worked. . . . I was making about seven Gs [$7,000] a week and paying people. Plus I had the seven [thousand] in my pocket. It was a good business.

Other important street survival skills are described in the following narrative by Hector, a 30-year-old Puerto Rican man. In this instance, quick hands and the ability to win confidence and exploit other peoples greed are combined to create an effective street hustle:

I go to stores and steal coffee and stuff like that, cigarettes. Twenty bucks worth, cigarettes and coffee. . . . Im going one by one. I be hitting little stores. Ill start from one end of Ames Street and head to the other [end]. Take one, two coffees from this store and two from the other. Until I get to the end of Ames Street and that is where I sell them, to the same people that I be taking them from. . . . If I steal something from this store, I take it to [that] store and sell it to them. . . . If I steal a carton of cigarettes and go and sell it to a store, they give you only $10 for the carton. Thats only a dollar a pack. A lot of them trust me. They be sending me to get [i.e., steal] shit, like Tylenol and stuff like that.

Significantly, this story affirms the degree to which street drug users are an integral part of an informal (and illicit) component of the small business market economy (Johnson et al., 1985; Preble & Casey, 1969). Reviewing these narratives, the key elements of street skills appear to be knowing how to read people and situations, knowing how to manipulate or coerce others, and being prepared to take opportunistic advantage of all situations. For example,

Ive used this once this week. . . . My dad lives in Michigan. So, hes not aware of the fact that Im on welfare, the state welfare, it pays for my medication. So I just come up with what I need [and tell my dad] I dont have the stuff [medicine] that I use everyday. So I talked my dad into sending me the money, like I need all these things. So hell send me the money Federal Express or Western Union. . . . So, Im like him, hes a salesman. And Ive learned a lot of tricks from him over the years.

Notably, this narrative suggests a way in which drug users transfer skills from mainstream society (i.e., skillful salesmanship) to street survival. Also critical to making it as a street drug user is the ability to recognize unexpected or sudden opportunities to get drugs or money (or other things of value) and to quickly act to take advantage of these chances, as illustrated in the following narrative:

You know its weird, well, its not weird, but people who do drugs, theyre always thinking, theyre always thinking about ways [to get drugs]. Its like looking at the next day even though its this day. But the next day is coming right around the corner. And you know, you can only do two bags and your high is usually four or five

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD DE ANTIOQUIA on July 31, 2013

Singer et al. / STREET NARRATIVES OF DRUG USERS

597

bags in a day, so your mind is pushing for the next day for how to get high and when to get high. . . . Like, I havent had a lot of money this past week. And I just sent my ex-wife . . . well, I didnt make her, I asked her. She took back a wedding gift that she got for her sister at Victoria Secret, and [she] gave me the 40 bucks that she got, well, 48 bucks. . . . [She] didnt go to the bridal shower. Because she was fighting with her sisters because nobody would pick her up to take her to the bridal shower. . . . So, I persuaded her to take it back to Victoria Secret and she gave me the money.

Survival skills also are needed in prison, a frequent place of residence of street drug users, as depicted in the following narrative told by Kyle, a middle-aged African American man:

I used to work in the hospital [in prison]. My job was in the hospital. I set up all the stuff for the doctor [e.g., syringes]. So, I was the guy selling the needles [to other inmates]. I had access to needles; theyd tell me to destroy them [after use with a patient, but] Id put them [aside instead]. . . . You know . . . they sent you up on different floors, like guys with low crimes on the first floor. Bigger crimes on the second floor, bigger crimes on the third floor, highest crimes on the top floor. . . . So, I always went straight to the top floor. Those were the guys that had the COs [correction officers] running the drugs [in] for them. So, Id go over to them and . . . every morning those guys would say, Look man, I need fresh needles every day. So, thats how I took care of myself [i.e., his drug addiction] in jail. You need five set ups [syringes] every morning, you got them. Now grab me a couple of bags [of drugs]. And theyd give it to you man, no questions, no wait. When I got there [to the cells of customers], theyd slide that shit [drugs] under the door. . . . I took care of the guys! Its something that you learn.

Stories such as these invert the common image of street drug users as social failures and people lacking the intelligence or skills to succeed in regular society (e.g., Fleisher, 1995). Rather, these narratives portray efficacious individuals with notable abilities, people who make things happen and get things done even under trying circumstances. Whatever the veracity of these stories, they reveal, by the cultural elements they express, that contrary to the assumptions of straight society, drug users embrace conventional action- and achievement-oriented cultural values. Whereas street drug users commonly are seen as socially marginal individuals, their stories appear to give voice to noticeably mainstream concerns and ideas. Also found among the adventurous narratives of drug users are stories that tell of close calls, narrow escapes, and heroic rescues. Commonly, these narratives emphasize the grave threats that drug users face each day on the street. Illustratively, Stuart, an African American man in his mid-40s, told the following story:

I think a lot of people dont want to be around these kids [gang members involved in drug dealing]. These kids are dangerous. They are very dangerous. . . . Youve probably been to Baltimore Street If you go there, watch the kids. Its all Twenty Love [a drug-dealing gang]. On the left side [of the street], its Twenty Love, [and] on the right side, its Solids [Los Solidos, another gang]. They sell the dope [heroin], and Twenty Love sells the caine [cocaine]. And if you ever watch them, sometimes youll catch drive-bys [drive-by shootings] and shit like that. I went to cop over there one night and they were doing drive-bys, and there was like four [cars] went by back to back. Bullets was whizzing by my head and all I could hear was it, and I was like, Oh, shit! And you dont know where to duck because a bullet is going by your head like that, you hear it, and are, Damn that just missed my head.

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD DE ANTIOQUIA on July 31, 2013

598

QUALITATIVE HEALTH RESEARCH / September 2001

Oftentimes, narrow escape narratives involve mistaken identities in which the wrong person or, alternately, a substitute (e.g., an accessible friend of the intended victim) is targeted for some form of retribution stemming from a violation of trust in the drug trade (e.g., receiving drugs to sell and not turning in the money), such as the following:

I had all this money, you know, like $500 on me. And the White boy had like $500 on him. . . . We must have got over a hundred bags of caine. . . . So we said, We gonna get us a nice girl. So we saw this girl and said, Yo, you want to get high, you want to come back to the carnival with me? And she said, Yeah, but I got my own place, we can go up there. . . . So we go up to her apartment. She lived up on the 16th floor. So we get up on the 16th floor, and a little baby was up there running around by himself. Little baby, you know, must have been like 3, 4 years old, running around by himself. And the girl, I hadnt noticed at first, but then I got a good look at it, she was pregnant. . . . One of her girlfriends knocked at the door, and then she called over another girl. Now the girls are naked in there and they cutting the music on high. . . . Someone knocked at the door and she went to get it, she said it was her girlfriend. [But] it was like six, seven dudes, you know, gang members. Yo man, your boy owe us some money, [one of them said]. [I said,] Im [from] way in New Jersey. I aint never been here but a few times to cop. But, you know, they like, Your boy owe us some money man, you got to pay too. We gonna fuck you up. I said, Damn, motherfucker, howm I gonna get out of this right? I said, Hey man, this what I got man, but I got more money back at . . . the carnival [where he worked]. Youll have to keep him here, Im gone. Ill go get the money and come back. They said, No man, dont do that. So, we just gave him all the coke we bought.

Great escapes from the police are also common:

So, we was on the highway. I was smoking [rock cocaine] just looking around. He was just driving. He was like doing 50 on the highway at night. The next thing you know the narcs were pulling us over. I rolled down my window, I just shot the stem [cocaine pipe] right out the thing and the lighter out the window. My brother, I dont know what he did with the cooker or whatever. I think he slipped it under the seat or something. The needle, I dont know what he did with it. They took us out of the car. They searched us and everything. They made us drop our underwear, lift up our socks, everything. And they didnt find nothing!

Another group of adventurous narratives involves gory or sickening events that served to underline the often brutal and frightening side of street drug users lives. For example, based on his prison experiences, Kyle shared the following gory event narrative, a story that also emphasized his survival skills:

I was in with diabetics. I fed the guys in quarantine [e.g., AIDS patients]. . . . You got to go in that cell to give the guy a tray [of food]. You got to know how to deal with that kind of stuff. Im just lucky enough that I know how to do that. Most of the COs couldnt go in there because they knew they was going to wear food [i.e., have food thrown back at them]. They [the COs] are the ones that put them in there. You gonna go in there and give them liquid? Some hot liquid? Hes gonna throw it on you. So, you know, we were the ones to go in there and do that. . . . Or I seen guys get hit with a bag of shit. In jail, guys get hit with a bag of shit. Guys save it up for a whole week, just for that CO to come there.

In this type of story, drugs and violence often combine to produce tragic endings, as seen in the following narrative:

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD DE ANTIOQUIA on July 31, 2013

Singer et al. / STREET NARRATIVES OF DRUG USERS

599

My biological brother, Damien, was over there getting high. He was 19 years old when he died. I was 11. He was in somebodys house. I guess he started to OD [overdose on drugs]. They tried to put him out because they didnt want him to die in their house. He was fighting to stay in. And they started stabbing him and stuff and pushed him out into the hallway, and they let him die in the hallway. And he was doing dope and cocaine together, speedballing, you know. I guess it froze his heart or something.

Tito, a Puerto Rican man who has been using noninjection drugs since the age of 8, told the following story that also fits this subgroup of street tales:

I dont like needles. When I go to jail, they want to take a blood test, they [always] give me a ticket cause I refuse to take a blood test. I seen this one kid in jail once, he went to get a blood test and I was after him. Im sitting in the same room when the lady [nurse] is sticking him. She stuck him four times in this arm and like twice in this arm. . . . So ever since that, I refuse and if they want to give me a ticket, just give me a ticket. . . . Ive seen people in the hallways [of his apartment building] still with it [the syringe] in [their arm]. Ive seen this daddy who was doing coke in the vein . . . and the guy got scared and he freaked out and the needle broke in his veins. I dont know if he died but [he had] a belt wrapped [around his arm] and he tightened it up even more [and] he just started screaming. . . . I almost started screaming myself when I seen that. Im scared of needles, hmm, hmm. . . . [And] about 2 years ago, I was . . . smoking [crack] by myself and I met these two guys. This Black kid, he had a glass pipe and the other kid he smokes and shoots up. I [had] $100, and I [bought] 13 dimes [13 bags of cocaine], came back, and I smoked it with the Black guy and gave the kid whatever. A couple of hours we were going straight without stopping and I ODed on it. I fell out, my mouth got full of saliva and I dont know [what happened]. I woke up and somebody was, you know, I was getting hit in my face. I just jumped up and I grabbed him and he said, Come on, calm down, you ODed this and that, you fell out. My arms hurt, I fell on bricks and the floor the dude was telling me. . . . I know if it wasnt for him, I would have probably died.

The latter part of Titos narrative is also suggestive of another group of adventurous stories, a subtype we have labeled heroic rescues and narrow escapes. Similar to Titos, some of these stories involve surviving drug overdoses. For example, Kyle relayed the following experience from his time in prison:

I told my CO, Man, open my cell door. Its time for me to work tonight. He said, All right, I got you. Only, I just sat in my cell and got off [with drugs brought in by another CO]. I was like, Man, this aint that good. Then I got off again. Next thing I remember, the medic is waking me up. . . . He said, Im talking to a dead man. You was a dead man! . . . The only reason Im here is because you didnt show up for work because you never miss work. He knew what I did. He was really cool about it, lets leave it at that. But I actually died in jail. He saved me.

Miraculous gains. We have labeled the third primary theme miraculous gains because they involve stories of unusual success or fantastic discovery. Again, several subtypes can be identified. For example, the following narrative is an example of a subgroup of miraculous gain tales that concern great finds or discoveries, often of money or drugs. In this instance (a narrative that also includes the theme of outstanding street skills), the discovery includes both money and a car:

The first time I stole a car here, I wasnt even trying to steal the car. I was just stealing the radio. And when I was inside, I found some money, where I found the money, I

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD DE ANTIOQUIA on July 31, 2013

600

QUALITATIVE HEALTH RESEARCH / September 2001

found a spare key to the car. So there was a key in there! It was far away from where I was [living], so I thought, Well, let me take a ride over to where I am [living]. So I took the car for a month. [Then], I called the owner to get a reward. She gave me 20 bucks to give it back to her. I guess she already had the insurance company set up for it. But . . . she gave me the money, saw the car, and I left because I thought she was going to call the cops. I left for about a week and a half. When I came back, the car was still in the same place. So, I started using it again.

A second subtype of miraculous gain narrative we refer to as big scores, such as the following example:

When I say do em, I mean I might bring him [a street drug dealer] back here in this back alley and say, Give me five dimes [five bags of drugs]. And when he pulls it out [to sell it to me], I stick him up. I take everything [all the drugs and money] from him. I pull out my pistol and take everything. You stick it right in his face, right in his face. Stick it right in his mouth. You know what time it is! He just give it to you. I tell him, You know what time it is. He got a pistol in his mouth, he gonna give it to me, believe me, he gonna give it to me, happily. Ive never had a problem with them. Ive caught [robbed] thousands and thousands, 7, 8, 9 thousand [dollars at a time]. [Then you] haul ass. He aint gonna chase you. Especially when he has to put his clothes back on, cause Im gonna make him pull them down. By the time he gets his pants up and buttoned, Im out of there, Im gone! And he doesnt know me from Adam. The only place he might see me again is jail.

A third subtype of this group of narratives we refer to as uncommon generosity. Diane, a 38-year-old White prostitute whose life in recent years has consisted of repeated arrests and periods of imprisonment, relayed the following narrative:

This police lady saw me, so she started talking to me and I was like, Oh no, shes gonna check my name. . . . Last time I had like six warrants, the last time she checked my name. . . . She was in the car, she stayed in the car [and] she asked me how I was doing and everything. . . . All of a sudden after she left she came back with two cruisers. And I was like, Oh, man, I knew it. I told her I was going to be dope sick [suffer from heroin withdrawal] and she took me home. . . . I did half a bag of dope, I smoked a cigarette. She let me change my clothes . . . so I wont be freezing in the cell. She stood right next to me . . . to make sure I wasnt gonna bolt . . . because last time I did bolt.

Although street drug users generally see themselves at the mercy of the police and have many tales of police cruelty toward them, including tales of beatings, confiscations, and coerced sex, in this instance, a police officer reportedly showed unusual generosity and allowed an arrested drug user to inject heroin one last time prior to going to jail for the weekend (while awaiting a Monday morning appearance in court). Another example of uncommon generosity was shared by Rita, a White heroin addict:

I was down on Ames Street, you know where these young Black kids hang out. And this kid calls me over, and Im thinking, Oh God, what did I do? This kids gonna fuck me up or something. But I went over there and he says, Hey, I seen you around here. Take this. He gave me a bag of dope. I couldnt believe it.

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD DE ANTIOQUIA on July 31, 2013

Singer et al. / STREET NARRATIVES OF DRUG USERS

601

As in the previous story, an individual who normally is seen as a threat (in this case, a street gang member) acts in a way that is completely counter to the storytellers expectations. Instead of being cruel or hurtful, the youth in this story demonstrates inexplicable generosity. Although, as noted in following sections, drug users tell many stories of ruthlessness and inhumane treatment at the hands of others, they also share contradictory experiences that affirm that even on the street they experience and are moved by moments of human kindness and benevolence. Sometimes, as in the following tale set in an abandoned building that is commonly used for illicit drug consumption, charitableness emerges unexpectedly in the midst of aggression:

I was up against the corner, and I was sitting on that little bench, the little couch. A guy came up and said, Give me everything, your watch, everything. He had a knife. . . . He had me trapped in the corner. And the way he had me, you know it was like, give it up, and this and that. And see, if I had seen it coming, I would grab . . . you see, I always carry a bottle. . . . Ill crack that over someones head. Theyll think twice about robbing me with a knife or not. . . . I think he was using ready [cocaine]. He probably wanted to get a hit, because I had dope on me and he came in with a girl. And he was like, Give me the dope too! And she was like, No, just leave him with the dope. Ill take one bag. So they left me. I had three bags [of heroin], so they left me with two bags. She took one. He was like, Give it all up! And I was like, Yo man, Im sick, I need it. And the girl was like, No, grab one and leave him with two.

More frequent than positive accounts of others are tales that describe ones own kindness and generosity. Genaro, a 34-year-old Puerto Rican man, provided the following example as he talked about the types of locations he has used to get high:

[The building we use to get high in is] empty. Ill never do something like that where people live. I respect kids. . . . When we go there, everybody got their own stuff [drugs and drug paraphernalia]. But, one time I split a bag with a guy because that guy was real sick and I dont like to see that. If I can, I give you a little bit because I know and [can] imagine how you feel when youre sick. . . . I put like 10 [units of liquefied drugs] in my cooker and the other half I gave to him. So he do it and I do mine.

In the following narrative, John describes how he put himself at considerable risk of injury to let a friend know that she did not have to turn herself into the police immediately (based on information given to him by a bail bondsman):

I been avoiding the Ames Street area because I was in some trouble over there. . . . It boils down to money and getting jumped on and whatever, so Im staying away from that area. . . . I did break down and go to see Debbie on Friday. I went into that neighborhood just specifically to see her. . . . I did go over there for Debbies sake and I did take a chance doing that. . . . Because I was concerned for Debbie, I put myself in a jeopardizing position, to look out for Debbie once again. . . . And of course, she was, you know, messed up. Shed been, you know, trying to get the last buzz before she goes in [to jail].

Not like the old days. In telling tales that highlight ones own attributes, participants often lament the shortcomings of others or the general deterioration of social relationships in the drug scene. For example, the following narrative by an older

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD DE ANTIOQUIA on July 31, 2013

602

QUALITATIVE HEALTH RESEARCH / September 2001

drug dealer contrasts the way he treats his customers compared to younger, upand-coming street dealers:

Pagers, [thats] another word for those who run the streets looking for [drug] customers. They forget that those are the people that are putting money in their pocket. But they dont look at it that way. They dont have the respect. . . . I mean, I appreciate the man who knocks on my door spending money with me. I want him to . . . I want my business. But at the same time, I am going to treat them somewhat good. . . . But, you know, if you go out there [in the street] and see these kids [who sell drugs] today, snatching money, Take this motherfucker and be happy with it! and all of that. . . . Compared to the old time . . . yeah I want customers, so I take care of them, blah blah blah, cause I want them to come back. I have to respect them. These young kids dont have it.

Another expression of how the drug scene is not like the old days involves an asserted decline in the quality of drugs, a very common topic of participant narratives. For example:

Ready rock [crack cocaine] is so cheap. It is so cheap. And they got some of those pushers on the street, they got shit thats full of baking soda. . . . You know what I mean? Its all screwed up with baking soda. . . . Let me tell you something about New York. New York has a thing, guys [drug dealers] in New York . . . they know when Hartford people are coming [to buy drugs], they know when Jersey people are coming. You know what I mean? They go around the first of the month: Okay, lets get this package ready for Hartford. Hartford doesnt have the best dope. . . . You know what I mean? They give Hartford like third-degree dope. Thats what these people are used to.

Ironically, street drug users in New York also complain about the declining quality of drugs in their city (e.g., Waterston, 1993). The power of drugs. Despite the frequency with which drug users complain that drugs today are not nearly as good as in the day (a common phrase that harkens back to the good old days of the past), their narratives nonetheless emphasize the considerable control drugs have over their lives. One subtype of this group of power of drugs narratives involves often excited accounts drug users tell about their first major drug experiences. Caliph, an African American cocaine user, for example, described his first encounter with crack in great detail in the following narrative that combines first-use and learning the ropes themes. In this instance, the effect of first exposure to crack was sufficiently powerful to begin a long-term crack addiction:

One day, me and a friend of mine, we said, Well, were gonna go out and get some cocaine. So, I said, Sure. I tried it a little bit when I was in the army . . . but I never smoked it. So, it was payday. We settled in to get some girls and you know we picked up some cocaine. I put in 80 [dollars], he put in 80, and a friend of his came with us, and he put in 80. . . . We stopped at a crack house. I didnt know anything about it. I thought we were going to sniff it. . . . So, they put it in some vials, some test tubes and started putting water and baking soda in and stuff. And, I said, Hey, you fucking up the caine. Man, what the fuck you doing? He said, No, Im cooking it. So, I sat back and watched what they were doing. Put some fire underneath it, to heat it up. It started bubbling and it came to a boil. Then the water started discoloring from gray to clear and then you saw a rock, a piece of jelly-like whitish thing

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD DE ANTIOQUIA on July 31, 2013

Singer et al. / STREET NARRATIVES OF DRUG USERS

603

floated in there. And they dropped it down in some ice water, and the next thing you know its like click click click and it was a rock. So Im looking cause I never saw nothing like this before. . . . So, I saw the guys, they took it, and they cut a little piece of rock off and they put it up on the screen, lit it up and started smoking. . . . Then I looked at his reaction. He stood up, opened his eyes and said, Whoa, that went down good. So, I said, Yeah, let me try that. . . . So, when I hit it, I . . . pulled down real hard and the pipe turned crystal ball white inside there. . . . And thats when it hit me. It was like my ears started ringing. And um, like a big rush. And my brain, like it was the rush in, it was a good feeling that lasted for about 2 minutes. . . . And then I wanted another hit real bad.

Another group of narratives that extol the power of drugs over the lives of drug users consists of descriptions of the regular and seemingly uncontrollable consumption of startlingly large quantities or varieties of illicit substances. Maria, a Puerto Rican woman who was trying to get into a drug treatment program, for example, described her previous level of addiction to heroin in the following words:

When I was really deep in dope, I was doing . . . four, five bundles, a bundle is 10 bags, so I was doing four bundles a day. I was selling [drugs] for the Dominicans. I was making $14,000, $15,000 every 2 days and I was making a $1,000 for myself, but it was like whatever money I was making, I was getting . . . in dope so I can do it. I was doing like 4, 5 bundles a day . . . at $100 a bundle. . . . When I was really deep deep in the dope, every 20 minutes shooting a bag.

If true, this level of heroin use would be noteworthy because it resembles descriptions of cocaine bingeinga practice that emerged in response to the much shorter duration of a crack high compared to a heroin high (Booth, Watters, & Chitwood, 1993). The intensity cocaine bingeing can reach is seen in the following account:

My mother . . . after the accident, she settled for a large amount of money. . . . Before, about a year ago, we were spending, me and my brother and my mother, at least $7,000; $8,000 each a day. We would just go get in the car and go down there [and] say, Yo, what you got, oh you got a ball [of cocaine], sell me a ball, give me a ball, you know, $100 worth. Go back and each of them would grab [some] and go back to the house and half an hour later be back down to get some more. If the money runs out and we cant get to the bank at 4:00 in the morning, then we just wait till 9:00 in the morning, go to the bank, take about $3,500 and thatll go quick.

Also encountered in this group of narratives are stories of unlimited, anything goes, polydrug use, such as the following example:

I was dropping a lot of acid [LSD], I was eating a lot of mushrooms, I was smoking pot, I was doing meth [methamphetamine]. I was doing everything. I took everything and anything. Opium, peyote buttons, anything! I took [anything], I did it. . . . People couldnt understand what it was like, do you know what I mean? I was caught in a trip. I was sniffing [cocaine]. I would smoke small like a quarter a week [of marijuana]. I was drinking about a 6 to a 12 pack a night, which was a lot. I was drinking a lot.

Another subgroup of narratives that stresses the power of drugs over the lives of addicts involves various stories suggesting the many trials and tribulations drug users are forced to endure because of their involvement with drugs. These narratives of things you have to put up with include tales of harassment and hardship of

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD DE ANTIOQUIA on July 31, 2013

604

QUALITATIVE HEALTH RESEARCH / September 2001

various sorts. For example, the following story portrays some of the ordeals associated with having to deal with street gangs because they control the drug trade:

Ive gotten high one time in one of the worst [housing] projects in the country. . . . They have 17, 18 floors, some [buildings] even [have] 28 floors. Each floor has like 30, 40 apartments in there. Each building has its own gang. And the police dont go there. If they need someone, they send the gang up to get it because the gang maintains order up there. Because they got to sell their drugs. So there is a place, a floor where theres no apartments. And theres a guy sitting in there with a shotgun. The gang runs the building. . . . Theres a guy in the hallway with a shotgun. And one in the elevator with a shotgun. And you get off on the floor and theres a [door and] the peephole is open. You stick a dollar under the door. And they stick a pipe, its a long, long glass stem, through there. And you pull [inhale on the pipe stem]. . . . And when you stop, they pull it back. And the guy with the shotgun pushes you. This is no joke, he pushes you, right. If you got more money, there are people behind you. You have to go all the way back [to the end of the line].

Suffering and regret. Disproportionately, female drug-user stories fall into the narrative category of suffering and regret. For example, Milagros, a 35-year-old woman, shared the following enduring suffering story:

I started smoking, thats how my addiction started, and I did it cause I had a lot of problems with my dad. He . . . hit me all the time, without any reason. Every time he went by my side he would slap me. He did this since I was 12 until I was 16, and he made me so nervous all the time. My nerves were totally destroyed, and that problem made me start the cigarette vice and then, right after that, I started to use pasto [marijuana]. Thats when I was 16. I had to leave my house because he ran after me with a machete. He got upset sometimes cause I was talking to a guy. God forgive me, but I think that even though he was my father he was interested in me. . . . He locked me in the house all the time and I told him, Im not gonna be yours. Thats when he really got crazy and he said he was gonna kill me with the machete. So thats how I started smoking cigarettes, cause I needed to calm my nerves. . . . And then I started smoking pasto, and with that it was easier because I could relax more and forget about my problems.

Another woman reported,

I thought that if I would leave him, my kids, you know, theyre going to suffer because they didnt have a father and stuff like that, so I stayed, but after 3, 4 years, I left. . . . He broke my leg. He pushed me down the stairs and broke my leg. You know how you get black and blue and stuff like that? He used to hurt me like that. My body was all sore.

Male narratives about suffering often are tied to the pain of drug withdrawal (Connors, 1994), such as the following:

Well, I was trying to get off, I had the bag in my hand and cops coming in. I tried to open the bag as fast as I can, but I cant. Theyre already there. And that is the way it happened [he got arrested] both time. . . . Probably about like 7, about 6:30, 7 in the morning. Im dope sick, and I have to stay in lock up all the way until I get out to go to [the court]. You have to be there 5, 5 hours before they let you go. Four hours is forever when youre sick.

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD DE ANTIOQUIA on July 31, 2013

Singer et al. / STREET NARRATIVES OF DRUG USERS

605

Another subtype of the suffering narrative has the theme of regret, as seen in the following first-use account by a male drug user:

My neighbor downstairs was telling me, Give me a ride down to Cedar Point and Ill give you some smoke [marijuana], I have to drop off something. So I said, All right, fine, and I did it a couple of times. . . . And shes like, Here, heres a bag [of heroin]. I was like, What do I do with this? And shes like, Just sniff half and, you know, whatever. . . . This was like 2 years ago. And I did half a bag and I really liked it. . . . So then I did the rest of the bag the next day or something. So then, my other neighbor, he was a retard, you know, a junky for 28 years. So I asked him when I got paid one day, Let me get one or two of those things [bags of heroin]. Ill do a little here, a little there, it will last me the week. So I got a couple of bags, and it didnt last like I thought it would last. I mean, I found myself going back. I gotta say that dope really screwed up my life man! It took everything from me. You know . . . I cant blame anyone for it, and I cant say, Well, this person turned me on to it. I cant blame that person . . . no one introduced me to it. It would have happened sooner or later, whoever it was. But it was my decision to get more, and it was my decision to actually do it, to pick it up. It really destroyed my life in a matter of 6 months. It destroyed my life. It tore it to pieces.

As this story suggests, tales of regret often are infused by a sense of futility and fatalism. Although the teller of this tale takes full responsibility for his actions, there is also a strong element of inevitability, as if his fate were sealed long before the actual events occurred. By contrast, in the following narrative, recorded by a middle-age White male, regret emerges as an empowering force that led him to quit using drugs for a number of years.

I used to go to Thursday night parties. At the party that night, my son, who them days didnt do H [heroin] or knew anything about habits, wanted to get a drivers license, and as we were talking about it, my daughter chimes in and says, What about me? I say, in all sincerity: Kathy, I didnt know. So if you want your license go down to the MV and get your papers tomorrow and I will teach you too. So, now shes happy and so I jokingly said to her, Well, Kathy, now that you are gonna get your license, dads gotta get you a car. And she says, Yep! And I said, Oh yeah, Kathy, and what kind and she said a Corvette. And I said, Any particular color? And she comes right back with her musical little voice and says, Blue. I sit down and Im worked up because I realized that I was neglecting my childrens little lives. I was devastated. After a while, I went into my drawer, took out all of my [drug] paraphernalia, destroyed it and threw it away. I stopped outright and didnt get high for many years.

The dual themes of loss and regret related to drug use are also central to the following narrative by another male drug user:

I messed that job up [because of cocaine]. Not going to work, out getting high, missing time, calling in sick cause Im out all night getting high, aint got time to go to work cause Im getting high. So, they didnt have time for that. Cause they had a deadline. . . . So, that job was eliminated. . . . You know, Ive lost many good jobs from it [drug use]. I used to have so many pieces of art work that I used to keep, and stuff you know. Ive went out and sold them [to buy drugs]. Pictures of Malcolm X, Marcus Garvey that Ive drawn. Sold them! So I [only] have a limited supply of my personal art work left. . . . But, I havent sold my hands yet!

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD DE ANTIOQUIA on July 31, 2013

606

QUALITATIVE HEALTH RESEARCH / September 2001

This narrative further underlines the sense of great personal loss as a consequence of drug use reported by many participants in our study. It is evident from these narratives, in fact, that drug users often maintain an intense love/hate attitude toward drugs; drugs can bring unparalleled highs and exciting adventure, but they also deliver unimaginable lows and great physical and emotional suffering. Over time, drug users often come to emphasize the things drugs have taken from their lives rather than the benefits they derive from drug consumption. For example:

I drove my car down to Cedar Point and sold it for a bundle [10 bags, with a street value of under $100]. And that lasted a couple of days. And then I sold my tools, and they were like $10,000 worth of tools. I sold it for a grand [$1,000]. And after I sold my tools, I started stealing shit out of the house and either pawning it off or like selling my wifes high school ring and her jewelry and stuff like that, and my own stuff. Thats when she realized that something was going on. . . . And, she was like, Youre out. I dont want you here any more, get out! So I left, and I returned just to break into the house to steal stuff. You know, doing that crazy stuff. So, now Ive lost my family. Ive lost my job, my car. Ive lost my family now. Now I am on the street. I dont have a personal life. This is the winter time. Im real real sick. And I have to start breaking into houses and stuff like that. Taking other peoples stuff, you know. Which is not me. I have never done that kind of stuff before.

We have labeled the final subtype of suffering and regret type narratives betrayal stories. For example:

The police found me. I was hiding out and they found me. I was hiding out, getting high at someones house where nobody knew where I was except for them [occupants of the dwelling] and the police found me. In the morning, I woke up with a cop sitting on top of my chest with his hand on my throat, and I got arrested. So, only two people knew, end of story! I dont even like talking, it pisses me off because of the simple fact that I dont know to this day, and Ive never done that to nobody. And to have someone do that to me . . . and I went over there to make sure they had cigarettes, and sodas, and drugs, and whatever. They were upset, maybe thats why, I led them on. I know drugs do weird things to people. So, maybe when the cops are knocking on their door, they say Im right down the hall, go get him, blah, blah, blah, and boom, they did. Thats the only thing I can think of.

Lamenting betrayal by fellow drug usersusually in the form of not repaying a loan, taking ones money or other possession, not sharing drugs, or cheating in a relationshipis a common element of these kinds of narratives.

CONCLUSION

Ethnographers have strongly defended their use of qualitative methods, including the collection of informant narratives and life histories, with the claim of heightened research validity: By design, field-based qualitative research is deeply rooted in the immediacies of social life (Geertz, 1973, p. vii) and offers ample opportunity for verifying informant accounts, cross-checking descriptions, and triangulating various data sources (e.g., comparing accounts by two or more participants and comparing accounts by the same informant at two or more points in time). Consequently, the claim of greater accuracy has been reiterated as a rationale for including ethnography in AIDS-prevention research. We certainly do not disagree with this

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD DE ANTIOQUIA on July 31, 2013

Singer et al. / STREET NARRATIVES OF DRUG USERS

607

perspectiveindeed, it is the one that motivates much of the work of our research team. Still, as we listen to participant narratives, we think it fair to raise questions about the validity of some kinds of ethnographic data. More precisely, in the context of AIDS-prevention research, we are concerned with questioning whether street drug users personal narratives are reasonably straightforward records of actual lived events or are, in varying degrees, like quantitative data collected in formal research environments, fabrications. The general literature on narratives would certainly suggest that drug users, similar to all storytellers, merge immediate experience with culturally constituted imagination, objective fact with colorful fantasy, and the details of real events with rhetorical devices and culturally meaningful themes (Kane, 1998; Tedlock, 1983). Furthermore, our own field experience suggests that drug-user war stories serve a number of important functions, including impressing researchers (who pay fees for participation in research projects), defining a street persona, articulating feelings and values, constructing social worlds, and propping up damaged egos, a set of psychosocial influences that may nudge narrative accounts away from objective, close-to-actual-events veracity. Our examination of the narratives in our data set points to the existence of identifiable story types that reflect the cultural shaping of personal experience into conventional categories of meaning. Taken together, these narratives appear to group around a number of contrastive experiential sets, such as high (psychotropic effects) versus low (drug withdrawal), kindness versus abuse, trust versus betrayal, success versus failure and regret, and excitement and surprise versus burdensome routines (things you have to put up with) and enduring suffering. These intensely oppositional themes exist in dynamic tension within and across the narratives. Thus, fellow drug users appear in the narratives as both friends and foes, as do family members, gang members, the police, and most important, the very psychotropic substances around which drug users structure their day-to-day activities. Whatever the veracity of this or that element in any particular narrative may be, the dynamic and oppositional tension of the narratives very accurately reflects the actual experience of street drug use: Drug users both love and hate being on drugs and all that focusing their lives on drugs entails. The intensity of this conflicted involvement enlivens their stories, just as their stories construct and encapsulate core cultural meanings in their lives. In this specific sense, there is a validity to the narratives that transcends their adherence to the actual details of the episodes they purport to describe. Put simply, the narratives are culturally valid, whatever their validity from a scientific perspective as objective records of observable behaviors, events, and circumstances. Recognition of this fact, we believe, makes narratives a critical resource for AIDS-prevention efforts. For example, the dynamic tension expressed in the narratives suggests the importance of intervention programs being structured to be sensitive to the fast-paced change, sudden reversal, impermanence, and unpredictability that characterize street drug-user lives. Drug treatment programs, especially residential programs, tend to be highly structured, rule oriented, and somewhat rigid because they seek to control the disruptive highs and lows in the lives of drug users. AIDS prevention, often offered in nonresidential settings (e.g., during street outreach or in office-based educational groups), usually lacks the ability to structure the social lives and activities of its target populations. Consequently, AIDSprevention programs are forced to adapt to drug-user realities or suffer from lack of

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD DE ANTIOQUIA on July 31, 2013

608

QUALITATIVE HEALTH RESEARCH / September 2001

rapport and ineffectiveness. Ethnography and drug-user narratives provide important windows on these complex and contradictory realities, providing insights of vital use to AIDS-prevention initiatives. Peering through the window of drug-user narratives, certain potential lessons for AIDS prevention are recognizable. Three, in particular, warrant consideration. First, it is evident from the narratives that acts of generosity and caring are not expected, and hence when they occur, they are seen as a pleasant surprise. The stories underline the degree to which street drug users expect to be mistreated and abused in their social interactions, producing, as a result, a narrational celebration of unforeseen acts of kindness. Consistently treating participants in a caring fashion, based on a genuine appreciation of them as fellow human beings, is suggested as the appropriate orientation of educational and service programs that work with drug users. This suggestion is based on an interpretation of the unexpected generosity narratives as expressions of deep desire for an arena of beneficent interaction. Although all service providers who work with street drug users come to grow wary of their survival-oriented tendency to engage in manipulation or to be undependable, their narratives reveal both a hunger for acts of patient kindness and a strong valuing of caring behavior. Second, drug-user stories emphasize that they are quite wary of betrayal. Their personal narratives suggest that they expect others to fail them, although it is always, nonetheless, a painful experience. Avoiding actions that can be construed (rightly or wrongly) as betrayal, therefore, should be a critical program element in AIDS prevention. A keen sensitivity to the issue of betrayal with emphasis on carefully handling behaviors that might be seen in this light and developing strategies for avoiding acts that might be interpreted as violations of confidence, breaches of commitment, or duplicity is crucial to relation building with street drug users. Finally, the narratives emphasize the skills and abilities of drug users, attributes that fly in the face of their usual denigration as unproductive individuals who lack desirable qualities or useful talents. Reversing the usual course, by treating drug users as socially resourceful, knowledgeable, and goal-oriented individuals, is a way of engaging drug users in AIDS prevention. At the same time, the narratives suggest the value of recognizing and appreciating demonstrated acts of generosity and caring by drug users, traits that similarly are denied by social stereotypes that portray them as aggressively self-focused and completely controlled by their drug dependencies. In short, analysis of street drug-user war stories suggests these colorful narratives can be read as experience-based statements of underlying concerns and heartfelt wishes. Although these stories, similar to all human stories, undoubtedly are embellished and slanted to convey desired messages and meanings, they nonetheless contain important truths for prevention programs. Significantly, many of the truths conveyed by drug-user stories are, in fact, broader cultural truths that street drug users share with others in American society, namely, a desire for intimacy, a fear of betrayal, and a need for personal efficacy. Recognition of these commonaltiesas opposed to the extreme dehumanizing otherness to which street drug users are commonly subjectedmay be one of the most critical lessons for AIDS programs. These conclusions raise an important question for those engaged in AIDS prevention among drug users: As we formulate and test prevention messages and methods, how closely are we listening to the messages coming back to us from the very people we seek to assist?

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD DE ANTIOQUIA on July 31, 2013

Singer et al. / STREET NARRATIVES OF DRUG USERS

609

NOTES

1. This grant was funded through a grant from the National Institutes of Mental Health and Drug Abuse to the Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS, School of Epidemiology and Public Health, Yale University: Margaret Weeks; principal investigator, Merrill Singer, coinvestigator. 2. All names of participants, streets, and neighborhoods of the city have been changed to limit the possibility of violating the confidentiality of project participants.

REFERENCES