Professional Documents

Culture Documents

AGRARIAN (Land Distribution)

Uploaded by

Gibsen de LeozOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

AGRARIAN (Land Distribution)

Uploaded by

Gibsen de LeozCopyright:

Available Formats

AGRARIAN (Land Distribution) Introduction The research shall be devoted to farming, specifically, about the land distribution in the

Philippines and in the Bicol Region. The Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Law (RA No. 6657) was enacted pursuant to the constitutional mandate that farmers, under the principle of social justice, must be given due attention by the country through efficient land distribution and various programs as well as the establishments of rights and benefits of farmers. Other topics concerning farming shall also be tackled, so long as it is necessary to purposefully convey the focus of the subject matter. Here are the data gathered about the land distribution and the concept behind it as discussed by the IBON Foundation and its pertinence internationally, in the Philippines, the Bicol Region. IBON Internationals Comment on Global Rush for Farmland Acquisitions The proliferation of large-scale foreign land acquisitions (FLAs) in poor countries have been a matter of concern to the international community over the last two years. Civil society organizations have promptly raised the alarm over their lack of transparency and negative consequences. Many of these deals are tantamount to land grabbing that violate the right to land and right to food of small farmers , especially women , pastoralists and tribal people. These regulatory principles appear desirable in principle in order to mitigate the negative impacts of FLAs. However the various voluntary guidelines or codes of conduct being proposed by inter-governmental agencies to regulate FLAs have no teeth and therefore do not offer even minimal protections or offer means of redressing grave human rights violations that often arise from these deals. Indeed, countries that host these agro-investments are often poor countries in desperate need of foreign exchange, have weak institutional capabilities or have corrupt or subservient governments that turn a blind eye to the adverse economic, social, and environmental consequences that are associated with these deals. More importantly, this policy approach is premised on the assumption that the proliferation of FLAs is the unavoidable consequence of and/or legitimate response to increasing food insecurity, particularly for capital-rich but food deficit countries. It does not address the more basic problems that fuel the rush to FLAs and the factors that encourage them.

This policy brief discusses the drivers of FLAs and suggests policy actions for addressing these by way of making the world agri-food system stable, resilient, sustainable, and true to its fundamental role of feeding the worlds people. Food security for resource-poor but cash-rich countries is often identified as the main driver for the land deals. It is a valid concern. But analysis of the nature of the land projects and the players involved casts doubt on its primacy. For instance, the World Bank, using available evidence, found that at least 42% of the land projects do not involve food production (21%focus on industrial or cash crops, 21% on biofuels, and another 21% is split between livestock, conservation/game reserve, and plantation forestry). The Bank further found that the bulk of the investments come from agribusiness, industry, and financial institutions. These are entities who are not traditionally involved in upstream food production as their main line of business, and whose foray into foreign land deals is motivated primarily by the interest to acquire control over farmland as a valuable asset. This can be said especially of private financial institutions. Moreover, these are entities whose unchecked patterns of investment and resources use converged to create the food price crisis, along with the energy and financial crises. A few rich countries trying to secure future food or energy supplies, together with agroinvestors/speculators looking for new pro! t opportunities, are taking advantage of cheap land resources from poorer countries whose populations are even more food insecure all in the context of a more hostile climate, depleting oil and natural resources, and population growth. Farm Size Distribution of Sugarcane Farms in the Philippines Of the 43,935 sugarcane farms cultivated by 40,138 farmers nationwide, 81% are within the farm size category of 10 hectares and below. Small farms (5 has and below) account for 67% of the farms, 69% of the total number of planters but only 17% of total land area and 14% of production. The bigger farms (50 ha and above), account for less than 5% of the number of farms, less than 4% of the planters yet they cover 39% of the sugarcane areas and account for 44% of total sugar Production. In Bicol, there are at present 1,120 sugarcane farms cultivated by 1,114 farmers region wide. The average farm size distribution indicates that 93% of the farms cultivated by a majority of sugarcane planters are within the farm size category of 10 has and below. Small farms account 84% of the farms, 83% of the planters, 43% of the sugarcane areas and 42% of production. The bigger farms (above 25 hectares) account for less than 2% of the number of farms, less than 2% of the planters yet they cover 16% of the sugarcane areas and account for 17% of the total Bicol sugar production.

Micro-finance Incentives of Farming Cooperatives in Bicol The Center for Agrarian Reform and Rural Development (CARRD) lauded the Minalabac, Mataoroc, Sagrada, San Jose, Baliuag Viejo (MASSBA) agrarian reform community (ARC) Cooperative in Camarines Sur for its micro-finance initiatives in launching a credit program in their locality. CARRD is a non-government organization initially formed in 1987 to provide technical assistance to peasant organizations and formally established in 1989 to advocate for agrarian reform and rural development agenda. This notable feat of MASSBA ARC Cooperative spurs DAR for the full implementation of the Agricultural Insurance Program (AIP) and Agrarian Production Credit Program (APCP) to mitigate agricultural losses due to natural calamities and farm pests. The national government allocated P1 billion for the AIP to be implemented by DAR together with the Philippine Crop Insurance Corporation (PCIC) and another P1 billion for APCP which is a joint undertaking of the DAR, Department of Agriculture (DA) and the Landbank of the Philippines, DAR-Bicol told the Philippine Information Agency. The AIP is an insurance assistance that can be availed to cover rice, corn, high-value crops including livestock production of ARBs, DAR-Bicol said. The APCP meanwhile provides credit assistance to ARBs or ARB household through organizations or other conduits to support individual or communal crop production. Aside from loans to finance crop production, APCP also provides agricultural production agreement, financial management support and institutional capability building for ARBOs, DAR-Bicol told PIA. The program requires preparation of ARBOs to become credit conduits and priority is given to provinces with high records in land acquisition and distribution (LAD), DARBicol said. With the successful implementation of the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program with Extension and Reform (CARPER), more farmer-beneficiaries are enjoying the fruits of their labor from the land they till. The photo shows one of the hundreds of farmers from the far-flung upland barangays of Libmanan, Camarines Sur. Libmanan has more than 3,500 hectares of land that are yet to be distributed to qualified beneficiaries under the governments land distribution program.

CARP and Land Distribution: An Article by Sonny Africa of IBON Features

PD 27 was enacted. In 1971, 58% of all farms were fully owned but this fell to 47.5% in 2002; in terms of land area, fully owned farms accounted for 62.9% of total farm area in 1971 but fell to 50.6% in 2002. Although there was a decrease in the share of completely tenanted and leased lands, this did not translate into full ownership but only part ownership that implies a continuation of tenancy and lease arrangements. In fact, the Annual Poverty Indicators Survey (APIS) of 2002 reported that only 11% of all families owning land other than their residence had obtained land through CARP. Yet the government repeatedly declares achievements by successive land and agrarian reform programs including, most recently, the CARP. How does this reconcile with decreasing land ownership according to agriculture census data? Pro-Landlord The DAR and the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) reported a cumulative accomplishment of a seemingly impressive 6.4 million hectares or 79.4% of the target CARP scope of 8.1 million hectares with 3.8 million farmer beneficiaries from 1972 to June 2005. These figures seem to indicate that agrarian reform in the Philippines is well underway, albeit slowly. However, the current target scope represents a severe downward adjustment from CARP's original scope in 1988. Back then, the target for distribution was 10.3 million hectares, or some 85% of total agricultural land planted to crops and a third of the country's total land area. This was adjusted downwards by 21.7% in 1996 to the current scope of 8.1 million hectares following drastic cuts in coverage of both private and public lands. The reason behind these cuts may be rooted in CARPs pro-landlord orientation. CARP is not about free land distribution to the tiller which is the core of a genuine land reform program. Instead, CARP seeks to provide landlord compensation and require peasant beneficiaries to pay for land that they have been tilling for generations. Land reform under CARP is essentially a land transaction between landlords and peasants with the government acting as the middleman. The revised CARP scope represents a concession to big private landed interests. The target was adjusted downwards to accommodate CARP exemptions. CARP allows landlords to retain five hectares of land and an additional three hectares for each of the heirs. PD No. 27 had a retention limit of seven hectares each. Landlords used these as a loophole, hurriedly subdividing their landholdings and coming out with multiple titles within the limits. Yet the scope of exemptions even broadened far beyond just retention limits.

At least 60,000 hectares of land in commercial farms and plantations were exempted from 1988 to 1998 and these remain undistributed even as the deferment period has already expired. The Supreme Court handed down a decision in 1990 sparing commercial livestock, poultry and swine operations from CARP coverage. Belated land use conversion is also another way out where agricultural lands that have already been distributed are suddenly found to be, according to local land use plans or zoning ordinances, for residential, commercial or industrial use and hence CARP-exempt. Further, landlords also had the option to forego land distribution altogether through nonland transfer schemes, such as the infamous stock distribution option (SDO). The SDO adopted corporate stock sharing instead of land distribution to peasants. Aside from other production and profit-sharing arrangements, the SDOs leasehold arrangements supposedly guaranteed that, in farms under five hectares, the split of net produce between landlord-tenant would be 25-75. In the end, the revised CARP scope in 1996 only covered 3.0 million hectares of private land. This implies that 43.7% of total potential private land for distribution around 5.3 million hectares was exempted outright from CARP. The reductions in the scope of public land in turn accommodated vast tracts of government land leased or otherwise controlled by big landlords as cattle ranches, export crop plantations and logging concessions. Trends in CARP implementation also confirm its pro-landlord bias. Compulsory acquisition (CA) covering the largest chunk of privately-owned land (including commercial farms and plantations) and the most resistant landlords has the largest balance remaining among all land types. This is both in terms of absolute land area (1.3 million hectares) and as a percentage of its target scope (83.8%). It also accounts for the majority of total balance remaining (76%). The "over-performance" of voluntary land transfers (VLTs) by 82.8% is alarming. VLTs ostensibly provide for the direct transfer of land from landlords to the peasant beneficiaries, with the government no longer acting as the buyer (from the landlord) and the seller (to the peasant). Instead, government only becomes responsible for mediating the transfer and subsequent enforcement of the contract. The use of this particular CARP mode of land redistribution is alarming not only because the landlord is put in a strong position to dictate the terms of the contract with the peasant. More important, the landlord is put in a position to use VLT as a deception where there is only a bogus "contract" and no transfer of land at all. On top of all this, landlords have also profited immensely from CARP apart from what they had already accumulated through generations of land ownership. From 1972 to June 2005, total approved Land Bank of the Philippines (LBP) compensation to 83,203 landowners for 1.3 million hectares has already reached P41.6 billion ($783.2 million, based on an exchange rate of P53.115 per US dollar) in cash and bonds, or an average of P500,463 ($9422.25) per landlord. An additional P4.5 billion ($84.7 million) is earmarked for 2006. 5

Deceptive accomplishments The CARP's reported accomplishments are also dubious since various forms of bogus land distribution bloat the figures. The "accomplishments" include lands with registered certificates of land ownership award (CLOAs) but these have not been turned over to tenants who are still paying for their amortization. There is double counting where "mother" or collective CLOAs and the "individual" CLOAs under these are both tallied. In the most brazen cases, there are CLOA holders who still do not occupy the land because of outright landlord resistance. The numbers also include "encumbered" CLOAs prematurely released to beneficiaries for the sole purpose of padding reports. These CLOAs are stamped or otherwise annotated as "encumbered" because of unsettled payments and documentary requirements and do not yet give holders the same rights of ownership as regular CLOAs. Land has also been reported as distributed but in reality is inalienable or otherwise not suited for agricultural production. Apart from reporting dubious accomplishments, these reports also do not reflect cases of land being awarded but later taken away from beneficiaries. Landlords and rural elites exploit a legal defect of CLOAs and EPs that limits the security of beneficiaries' claim to the land covered. Torrens Titles have a one-year prescriptive period for bringing up cases against them as opposed to CLOAs and EPs that have no such limit. This gives landlords the legal opening to reclaim land by disputing the redistribution of land. CARP exemptions are used, albeit belatedly, as the basis for cancellations. They also maneuver decisions favorable to them through technicalities including supposed errors in data entries, in the change of documents from EPs to CLOAs and in the identification of legitimate farmer beneficiaries. These defects, loopholes, and outright corruption have resulted in thousands of cancellations through the years. Over 2,000 CLOAs and EPs covering over 380,000 hectares of land and thousands of peasant families had been cancelled by mid-2004, including EPs distributed over two decades ago. This is likely to be a gross underestimation though because DAR officials themselves admit that there is no nationwide mechanism in place to monitor reversals happening on the ground. Land conversion has also caused total farm area to fall to 9.7 million hectares in 2002, or 304,078 hectares less in 1991. This figure does not include land that has been "converted" only on paper for the landlords expediency. In addition, there are also land distribution reversals resulting from the economic pressures on peasant beneficiaries. Beneficiaries are hard-pressed to make the lands distributed to them productive because there are no support and extension services available to them. This comes on top of the generally unfavorable economic environment due to rapid agricultural sector liberalization in the 1990s and the dumping of cheap cereals, spices and vegetables from abroad. Falling farm incomes and mounting debt drive peasants to stop amortizing "their" land leading

either to foreclosure, a sale of the land back to the landlord (who continues the payments), or out-and-out abandonment. CARP accomplishment reports then do not reflect the hundreds of thousands of hectares of land that "beneficiaries" are losing back to landlords, commercial and real estate developers. In any case it seems that not all 2.1 million DAR CARP beneficiaries hold either EPs or CLOAs since there are only 1.7 million EP and CLOA holders as of December 2004. Poverty and landlessness The clear failure of land reform in the country has severe consequences for a predominantly agricultural country like the Philippines. The peasants who make up the largest part of the population continue to be exploited by rural land, credit, trading and marketing monopolies and are kept in miserable poverty. Rural poverty incidence is two-and-a-half times that in urban areas and 73% of the country's poor live in agriculture-dependent rural areas. Land rent is still common with tenants paying anywhere from 30% to, in some extreme cases, as much 90% of their produce to landlords. The tersyuhan arrangement of a two-thirds share to the landlord and one-third to the tenant, which happens in many coconut farms in the Bicol region, is among the most common. Farmworkers are doubly burdened with irregular work and even when there is work to be found low wages. Agricultural daily minimum wages ranged from P151-P212 ($2.84-$3.99) nationwide yet farmworker wages were found to go as low as P20 ($0.38) in Negros, P50 ($0.94) in Samar and P69 ($1.30) in Cagayan Valley. Peasants meanwhile have to contend with traders charging high prices for agricultural inputs like fertilizers and pesticides, while paying low prices for peasant produce. With peasant incomes perpetually falling far below their needs, usury's grip is deep with interest rates reaching the equivalent of 20% per month, 200% per harvest and 400% per year. In the province of Mindoro Oriental, P1,000 ($18.83) loans have been charged interest of four (4) sacks of rice, or equivalent to over four times the original loan amount. CARP cannot address peasant poverty and landlessness because it was never meant to. Thus, the only hope for genuine land reform in the country lies with the growing peasant movement. Organized peasant groups have directly confronted exploitation by landlords and traders. They have improved their livelihoods and welfare in ways that, unlike CARP, do not sidestep the issue of who should be benefiting from tilling and working the land. (Posted by Bulatlat)

You might also like

- Manual For ProsecutorsDocument51 pagesManual For ProsecutorsArchie Tonog0% (1)

- BCG Matrix For Dilmah PLCDocument4 pagesBCG Matrix For Dilmah PLCHaneesha Teenu100% (5)

- Razon JR vs. TagitisDocument6 pagesRazon JR vs. Tagitisgianfranco0613100% (1)

- Agrarian ReformDocument40 pagesAgrarian ReformYannel Villaber100% (2)

- DARAB RULESDocument43 pagesDARAB RULESGibsen de LeozNo ratings yet

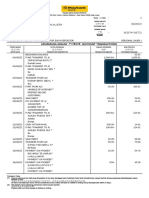

- American ExpressDocument1 pageAmerican ExpressErmec AtachikovNo ratings yet

- Facing The Challenges of The Philippine Coconut Industry The Lifeblood of 3Document74 pagesFacing The Challenges of The Philippine Coconut Industry The Lifeblood of 3epra100% (12)

- NotesDocument24 pagesNotesGibsen de LeozNo ratings yet

- Agricultural Development in The PhilipppinesDocument4 pagesAgricultural Development in The PhilipppinesJon Te100% (1)

- The Comprehensive Agrarian Reform in The PhilippinesDocument6 pagesThe Comprehensive Agrarian Reform in The PhilippinesKim BlablablaNo ratings yet

- Agrarian Reform in The PhilippinesDocument2 pagesAgrarian Reform in The PhilippinesChristian Belarmino CaparasNo ratings yet

- MBBsavings - 162674 016721 - 2022 09 30 PDFDocument3 pagesMBBsavings - 162674 016721 - 2022 09 30 PDFAdeela fazlinNo ratings yet

- Bond and Stock Problem SolutionsDocument3 pagesBond and Stock Problem SolutionsLucas AbudNo ratings yet

- Analysis On Agriculture in The PhilippinesDocument4 pagesAnalysis On Agriculture in The PhilippinesGeorgette Alison100% (1)

- Project Implementation Policy KPK 2023Document62 pagesProject Implementation Policy KPK 2023javed AfridiNo ratings yet

- CC Stat222Document2 pagesCC Stat222darshil thakkerNo ratings yet

- Indian Income Tax Return Acknowledgement 2022-23: Assessment YearDocument1 pageIndian Income Tax Return Acknowledgement 2022-23: Assessment YearParth GamiNo ratings yet

- The State of the World’s Forests 2022: Forest Pathways for Green Recovery and Building Inclusive, Resilient and Sustainable EconomiesFrom EverandThe State of the World’s Forests 2022: Forest Pathways for Green Recovery and Building Inclusive, Resilient and Sustainable EconomiesNo ratings yet

- Agri Business NKDocument34 pagesAgri Business NKKunal GuptaNo ratings yet

- Tesco OfferDocument4 pagesTesco OfferAjay SinghNo ratings yet

- Handbook For Carp ImplementorsDocument92 pagesHandbook For Carp ImplementorsMaria Danice Angela100% (1)

- Philippines Barangay Dispute Certification Rental Non-PaymentDocument1 pagePhilippines Barangay Dispute Certification Rental Non-PaymentGibsen de Leoz100% (1)

- Farm Land Policy and Financing Program For Young Generation in The PhilippinesDocument13 pagesFarm Land Policy and Financing Program For Young Generation in The Philippinesmartin 1984No ratings yet

- Swaminathan Report: National Commission On Farmers: BackgroundDocument8 pagesSwaminathan Report: National Commission On Farmers: BackgroundAnonymous cC6CebWuNo ratings yet

- Farm Land Policy and Financing Program For Young Generation in The Philippines - FFTC Agricultural Policy Platform (FFTC-AP) PDFDocument12 pagesFarm Land Policy and Financing Program For Young Generation in The Philippines - FFTC Agricultural Policy Platform (FFTC-AP) PDFJoshua CoNo ratings yet

- Agrarian Reform Policies HistoryDocument8 pagesAgrarian Reform Policies HistoryElla Marie MostralesNo ratings yet

- SVPDC Jacky 10Document13 pagesSVPDC Jacky 10Bernard Jayve PalmeraNo ratings yet

- CARP Reaction Paper: A Look at the Philippine Agrarian Reform ProgramDocument3 pagesCARP Reaction Paper: A Look at the Philippine Agrarian Reform ProgramELIJAH NICOLAI MONTANONo ratings yet

- Prelim Performance Task 1 Problems of Philippines AgricultureDocument12 pagesPrelim Performance Task 1 Problems of Philippines AgriculturePrince CaratorNo ratings yet

- Vegetable Growing and Integrated Rice-Duck Farming System in Yolanda-Affected Areas in Eastern Samar: A Concept NoteDocument6 pagesVegetable Growing and Integrated Rice-Duck Farming System in Yolanda-Affected Areas in Eastern Samar: A Concept Notecarlos-tulali-1309No ratings yet

- DFI Volume 11Document166 pagesDFI Volume 11robo_anilNo ratings yet

- DFI Volume 11Document164 pagesDFI Volume 11Mamta JainNo ratings yet

- CARP's Failure to Improve Farmers' LivesDocument18 pagesCARP's Failure to Improve Farmers' LivesJAZMINE FRANCES ANGNo ratings yet

- AGRA LAW: How land access impacts food security and povertyDocument16 pagesAGRA LAW: How land access impacts food security and povertyLeandro AcunaNo ratings yet

- DFI Vol-12ADocument213 pagesDFI Vol-12ADanish NehalNo ratings yet

- What Needs To Be Done To Make Agriculture Profitable For More Farmers in IndiaDocument10 pagesWhat Needs To Be Done To Make Agriculture Profitable For More Farmers in IndiaBellwetherSataraNo ratings yet

- "Yes, But Not To The Fullest in My Opinion." - Threjann Ace NoliDocument2 pages"Yes, But Not To The Fullest in My Opinion." - Threjann Ace NoliJANNo ratings yet

- The New Thinking' For Agriculture: by Dr. William D. DarDocument13 pagesThe New Thinking' For Agriculture: by Dr. William D. DarLaurenz James Coronado DeMattaNo ratings yet

- AGRICULTUREDocument2 pagesAGRICULTUREJericho CarabidoNo ratings yet

- AVCF Philippine Country ReportDocument13 pagesAVCF Philippine Country ReportJoan BasayNo ratings yet

- Agrarian Reform: Unit 4 Agricultural Policies and Programs in The PhilippinesDocument15 pagesAgrarian Reform: Unit 4 Agricultural Policies and Programs in The PhilippinesJackelene TumesaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document7 pagesChapter 2Ephesiany BantawanNo ratings yet

- Voices From The Field Needs of Small ScaDocument11 pagesVoices From The Field Needs of Small ScaLiezel Jane SantosNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 11 - EconomyDocument31 pagesCHAPTER 11 - EconomyAli BudzNo ratings yet

- Activity 8 HistoryDocument2 pagesActivity 8 Historykeep smilingNo ratings yet

- Paper 859000900 PDFDocument32 pagesPaper 859000900 PDFJoanna RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Population Growth and Agricultural Development in KenyaDocument3 pagesPopulation Growth and Agricultural Development in Kenyadr_ashishvermaNo ratings yet

- DFI Volume 7Document187 pagesDFI Volume 7abhishek H M madegowdaNo ratings yet

- Agrarian Reform VS IndustrializationDocument1 pageAgrarian Reform VS IndustrializationalyssaNo ratings yet

- CARP Implementation IssuesDocument1 pageCARP Implementation IssuesBlaze Roxas PeraterNo ratings yet

- Agriculture and Land ProblemsDocument13 pagesAgriculture and Land ProblemsAshutosh SharmaNo ratings yet

- DFI Volume 4Document273 pagesDFI Volume 4Parshuram911No ratings yet

- Why agrarian reform promotes social justiceDocument4 pagesWhy agrarian reform promotes social justiceRachelle LausaNo ratings yet

- Agriculture in The Philippines Has Receded in Recent DecadesDocument2 pagesAgriculture in The Philippines Has Receded in Recent DecadesJocelyn Mae CabreraNo ratings yet

- CarpDocument8 pagesCarpRheinlander MusniNo ratings yet

- Agreform NuñezDocument3 pagesAgreform NuñezPiolo NuñezNo ratings yet

- Priority Issues: For Indonesian AgricultureDocument6 pagesPriority Issues: For Indonesian AgricultureSurjadiNo ratings yet

- Current Policies and AlternativesDocument3 pagesCurrent Policies and AlternativesAngel LucarezaNo ratings yet

- Agrarian Reform PoliciesDocument39 pagesAgrarian Reform PoliciesErica Kim EstrellaNo ratings yet

- HB 374 - Genuine Agrarian Reform BillDocument25 pagesHB 374 - Genuine Agrarian Reform BillanakpawispartylistNo ratings yet

- Congress Policy Brief - CoCoLevyFundsDocument10 pagesCongress Policy Brief - CoCoLevyFundsKat DinglasanNo ratings yet

- Agrarian LawsDocument3 pagesAgrarian LawsSultan Kudarat State UniversityNo ratings yet

- Lesson 6: Agrarian DisputesDocument2 pagesLesson 6: Agrarian DisputesSophia Marie DaparNo ratings yet

- CSO Declaration For The CIRDAP 2nd Ministerial Meeting, Dhaka, January 25, 2010Document3 pagesCSO Declaration For The CIRDAP 2nd Ministerial Meeting, Dhaka, January 25, 2010Asian NGO CoalitionNo ratings yet

- My Report in Rural Admin 1Document23 pagesMy Report in Rural Admin 1Abeb ArboledaNo ratings yet

- Status of Philippine AgricultureDocument4 pagesStatus of Philippine AgricultureKa Hilie Escote MiguelNo ratings yet

- Narratives of Land: The Current State of Agrarian Reform in The PhilippinesDocument4 pagesNarratives of Land: The Current State of Agrarian Reform in The PhilippinesmiellynhaNo ratings yet

- 1995 NAFTA and Mexico's Maize ProducersDocument14 pages1995 NAFTA and Mexico's Maize ProducersJose Manuel FloresNo ratings yet

- Agricultural Logistics Key to Doubling Farmers' IncomeDocument188 pagesAgricultural Logistics Key to Doubling Farmers' IncomeshruthinNo ratings yet

- Agricultural Logistics Key to Doubling Farmers' IncomeDocument184 pagesAgricultural Logistics Key to Doubling Farmers' IncomesyamskhtNo ratings yet

- Program Implementation of CARP: Leasehold Operations Is The Alternative Non-Land Transfer Scheme That Covers All TenantedDocument5 pagesProgram Implementation of CARP: Leasehold Operations Is The Alternative Non-Land Transfer Scheme That Covers All TenantedShairaah Medrano FaborNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Agrarian Land Reform ProgramDocument1 pageComprehensive Agrarian Land Reform ProgramChen C AbreaNo ratings yet

- The State of Food and Agriculture 2017. Leveraging Food Systems for Inclusive Rural TransformationFrom EverandThe State of Food and Agriculture 2017. Leveraging Food Systems for Inclusive Rural TransformationNo ratings yet

- It Is Most Important To Note That The Practice of LawDocument2 pagesIt Is Most Important To Note That The Practice of LawGibsen de LeozNo ratings yet

- We Are Faced Here With A Controversy of FarDocument1 pageWe Are Faced Here With A Controversy of FarGibsen de LeozNo ratings yet

- We Are Faced Here With A Controversy of FarDocument1 pageWe Are Faced Here With A Controversy of FarGibsen de LeozNo ratings yet

- The Ownership of A Land or Property Does Change Through TimeDocument7 pagesThe Ownership of A Land or Property Does Change Through TimeGibsen de LeozNo ratings yet

- SC Clarifies NLRC Rules of Procedure On Posting and Reduction of BondDocument1 pageSC Clarifies NLRC Rules of Procedure On Posting and Reduction of BondGibsen de LeozNo ratings yet

- The CENRO Deputy Public Land Inspector Explained That The Titling Services For Residential Lots Are Pursuant To Republic Act 10023 or The Free Patent Act of 2010Document1 pageThe CENRO Deputy Public Land Inspector Explained That The Titling Services For Residential Lots Are Pursuant To Republic Act 10023 or The Free Patent Act of 2010Gibsen de LeozNo ratings yet

- Your Filipino Cheese Pimiento Shopping ListDocument1 pageYour Filipino Cheese Pimiento Shopping ListGibsen de LeozNo ratings yet

- In Reinstating The Labor Arbiters January 28Document1 pageIn Reinstating The Labor Arbiters January 28Gibsen de LeozNo ratings yet

- Fishing Vessel Ownership and Illegal Fishing ChargesDocument1 pageFishing Vessel Ownership and Illegal Fishing ChargesGibsen de LeozNo ratings yet

- That Was Just One MistakeDocument1 pageThat Was Just One MistakeGibsen de LeozNo ratings yet

- Pcs OnionsDocument1 pagePcs OnionsGibsen de LeozNo ratings yet

- Bus company not criminally liableDocument2 pagesBus company not criminally liableGibsen de LeozNo ratings yet

- What Will MatterDocument1 pageWhat Will MatterAdam LohnerNo ratings yet

- Transpo Cases 1Document7 pagesTranspo Cases 1Gibsen de LeozNo ratings yet

- Personality Enhancement Program QuestionnaireDocument1 pagePersonality Enhancement Program QuestionnaireGibsen de LeozNo ratings yet

- CaseDocument1 pageCaseGibsen de LeozNo ratings yet

- Certificate To File Action1Document1 pageCertificate To File Action1Gibsen de LeozNo ratings yet

- TemplateDocument2 pagesTemplateGibsen de LeozNo ratings yet

- Personality Enhancement Program QuestionnaireDocument1 pagePersonality Enhancement Program QuestionnaireGibsen de LeozNo ratings yet

- TalusanDocument1 pageTalusanGibsen de LeozNo ratings yet

- The 2013 Bar Questions in Political Law For The First Sunday of The Bar Appear To Be Very ReasonableDocument1 pageThe 2013 Bar Questions in Political Law For The First Sunday of The Bar Appear To Be Very ReasonableGibsen de LeozNo ratings yet

- Contract of LeaseDocument2 pagesContract of LeaseGibsen de LeozNo ratings yet

- RedemptionDocument1 pageRedemptionGibsen de LeozNo ratings yet

- 1) Lorbes vs. CADocument1 page1) Lorbes vs. CAGibsen de LeozNo ratings yet

- Financing For Farmer Producer Organisations PDFDocument18 pagesFinancing For Farmer Producer Organisations PDFRaghuram BhallamudiNo ratings yet

- Improvement Plan Forsachin G.I.D.C.Document8 pagesImprovement Plan Forsachin G.I.D.C.GRD JournalsNo ratings yet

- Sample Co Hosting ContractDocument7 pagesSample Co Hosting ContractArte CasaNo ratings yet

- Finding and Correcting Errors on a Work SheetDocument10 pagesFinding and Correcting Errors on a Work SheetCPANo ratings yet

- Secured US Corpo LawDocument48 pagesSecured US Corpo LawROEL DAGDAGNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1 Introduction To Engineering Economy PDFDocument6 pagesLecture 1 Introduction To Engineering Economy PDFRheim Vibeth DimacaliNo ratings yet

- Capital Gains Taxes and Offshore Indirect TransfersDocument30 pagesCapital Gains Taxes and Offshore Indirect TransfersReagan SsebbaaleNo ratings yet

- WASKO - Studying PEM PDFDocument24 pagesWASKO - Studying PEM PDFrmsoaresNo ratings yet

- RefrigeratorsDocument9 pagesRefrigeratorsAbhishek Mahto100% (1)

- HdiDocument13 pagesHdiAmeya PatilNo ratings yet

- Case 14Document1 pageCase 14Jasmin CuliananNo ratings yet

- FIN338 Ch15 LPKDocument90 pagesFIN338 Ch15 LPKjahanzebNo ratings yet

- Human Resource Manab Gement 1 ModuleDocument75 pagesHuman Resource Manab Gement 1 ModuleNelly ChiyanzuNo ratings yet

- EES 2004: Exploring Fundamental & Chartist Strategies in a Participatory Stock Market ExperimentDocument16 pagesEES 2004: Exploring Fundamental & Chartist Strategies in a Participatory Stock Market Experimentliv2luvNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1 Malaysian EconomyDocument15 pagesAssignment 1 Malaysian EconomyRoslyna khanNo ratings yet

- List of Nbfcs Whose Certificate of Registration (Cor) Has Been Cancelled (As On January 31, 2022) S No Name of The Company Regional OfficeDocument474 pagesList of Nbfcs Whose Certificate of Registration (Cor) Has Been Cancelled (As On January 31, 2022) S No Name of The Company Regional Officesuresh gNo ratings yet

- Organization and Organizational BehaviourDocument9 pagesOrganization and Organizational BehaviourNoor Mohammad ESSOPNo ratings yet

- The Payment of Bonus Act, 1965Document36 pagesThe Payment of Bonus Act, 1965NiveditaSharmaNo ratings yet

- Premiums and WarrantiesDocument17 pagesPremiums and WarrantiesKaye Choraine NadumaNo ratings yet

- Soal Ch. 15Document6 pagesSoal Ch. 15Kyle KuroNo ratings yet

- Human Resource ManagementDocument3 pagesHuman Resource ManagementQuestTutorials BmsNo ratings yet