Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dellas Tavlas The Revived Bretton Woods System, Liquidity Creation and Asset Price Bubbles

Uploaded by

Eleutheros1Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dellas Tavlas The Revived Bretton Woods System, Liquidity Creation and Asset Price Bubbles

Uploaded by

Eleutheros1Copyright:

Available Formats

The Revived Bretton Woods System, Liquidity Creation, and Asset Price Bubbles

Harris Dellas and George S. Tavlas

In this article, we argue that the present constellation of exchange rate arrangements among the major currencies has led to the creation of excessive global liquidity, which has contributed to asset price bubbles. Although the exchange rates of many of the major currenciesincluding the U.S. dollar, the euro, the yen, and the pound sterlingfloat against each other, the currencies of many Asian emerging market economies and oil-exporting economies are pegged to the dollar. Dooley, Folkerts-Landau, and Garber (2004a) labeled this system Bretton Woods II (BWII).1 The original Bretton Woods regime (BWI) lasted for about a quarter of a century. Dooley, Folkerts-Landau, and Garber (DFG) argue that the present regime, despite its large global imbalances, will also be sustainable. We have a different view. In what follows, we argue that the original Bretton Woods system comprised two fundamentally different variants. The first variant lasted from the inception of the system in 1947 until around 1969. The second variant had a much shorter life span, lasting from about 1970 until the collapse of the system in 1973.

Cato Journal, Vol. 31, No. 3 (Fall 2011). Copyright Cato Institute. All rights reserved. Harris Dellas is Professor of Economics at the University of Bern, where he is Director of the Institute of Economics, and a Research Fellow of the Center of Economic Policy Research. George S. Tavlas is Director General of the Bank of Greece and Alternate to the Governor of the Bank of Greece on the European Central Banks Governing Council. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as those of their respective institutions.

1

See also Dooley, Folkerts-Landau, and Garber (2003, 2004b, 2005, 2006, 2009). 485

Cato Journal

Whatever may have been the underlying stability characteristics of the initial part of that system, the variant that emerged around 1970 was fundamentally unstableit was conducive to high global liquidity creation and asset price bubbles. We argue further that, to the extent that the global financial system has metamorphosed into a revived Bretton Woods regime, that regime resembles BWI from 197073, so that BWII is also prone to high global liquidity creation and asset price bubbles. The remainder of this article is structured as follows. First, we compare both variants of BWI with the BWII regime that emerged in the early 2000s. Next, we discuss the relation between international liquidity creation under the latter stages of the original Bretton Woods regime and the new Bretton Woods regime. We then present some concluding observations.

Bretton Woods: Old and New

The original Bretton Woods regime was a fixed exchange rate system in which Western European countries and Japan maintained undervalued exchange rates against the dollar, thereby accumulating large amounts of dollar reserves in the pursuit of export-led growth. The United States was at the center of BWI, playing the role of world banker, running balance-of-payments deficits, and supplying dollar reserves to other countries. As the worlds banker, the United States engaged in maturity transformation, accumulating short-term dollar liabilities while lending long-term, on net, to the rest of the world. Other countries pegged their currencies against the dollar. The United States, for its part, fixed the price of the dollar at $35 per ounce of gold, freely buying gold from, and selling gold to, official bodies at that price. During the 1960s, however, the U.S. Federal Reserve began pursuing expansionary monetary policies for domestic reasons, paying little attention to growing balance-of-payments deficits, especially at the end of the decade. As a result, the growth of global liquidity surged beginning in 1970, commodity prices exploded, and the Bretton Woods system broke down. Now, consider what DFG have dubbed the new Bretton Woods system. The revived Bretton Woods metaphor runs as follows: As was the case under the earlier Bretton Woods regime, the present regime consists of a center country and a group of

486

Bretton Woods

economies comprising a periphery. The center country has been the United States under both regimes. Under the old Bretton Woods system, the Western European countries and Japan were the periphery; the emerging economies of Asia, including China, are the new periphery. Under both regimes, there is asymmetric monetary policy, with the Federal Reserve ignoring external factors in setting interest rates, while policymakers in the periphery focus on external factors. Under both regimes, the periphery follows export-led growth strategies based on undervalued currencies pegged against the dollar. Under both regimes, the undervalued currencies give rise to a massive accumulation of foreign exchange reserves mainly in the form of low-yielding U.S. dollar-denominated financial instruments. Under both regimes, the United States provides the main export market for the periphery, validating the export-led growth strategies of that group of countries. As was the case in the earlier regime, the United States plays the role of world banker, providing financial intermediation services for the rest of the world, especially the periphery. The earlier regime lasted for 25 years. DFG argue that the present system, which they say began in the early 2000s, will also be long-lasting.

International Liquidity and Asset Price Bubbles

Although there is much insight in DFGs story, it overlooks a fundamental change that took place in the late 1960s and early 1970s namely, the United States severed the link between the dollar and gold. That change led to a surge of global liquidity, an asset price bubble, and a financial crisis, contributing to the breakdown of BWI. The fatal flaw of the revived Bretton Woods system is that it is also a pure fiat money regime with no anchor. We argue that flaw contributed to the asset price bubbles of the 2000s and the crisis that erupted in August 2007. To demonstrate, consider data on growth rates of international liquidity and commodity prices for 196069, 197074 (the final years of BWI plus a year added for lagged effects), 19752002, and 200307

487

Cato Journal

(BWII up until the year of the financial crisis). From 1960 to 1969 and 1975 to 2002, the average annual growth rates of global liquidity were 7 percent and 9.5 percent, respectively. During the final years of BWI (from 1970 to 1974), global liquidity grew by more than 30 percent a year, and under BWII (from 2003 to 2007), global liquidity grew by 17 percent a year. The growth in global liquidity led to a rapid increase in commodity prices in 197074 and 200307, as indicated in Table 1. We can, therefore, conclude that both global liquidity and commodity prices grew much more quickly after the dollars link to gold was severed. A more detailed explanation follows.

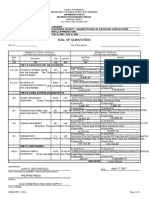

TABLE 1 Commodity Prices and International Reserves, 19692007 (Annualized Percentage Changes)

196069 Reserves Real GDP (world) Nominal GDP (world, U.S. dollars) Commodities Commodities Excluding Gold and Energy Energy Price of Gold 6.8 NA 7.5 0.9 1.4 197074 30.5 4.8 13.8 33.9 20.9 19752002 9.7 3.4 7.1 2.6 0.1 200307 17.1 4.1 9.7 21.5 17.9

-0.5 0.2

56.2 42.2

5.7 5.1

23.5 19.8

NOTES: Reserves are denominated in SDRs and exclude gold holdings. The index for commodities is based on the prices of 30 commodities. The energy component of the index consists of the prices of coal and crude oil. The price of gold is the spot price in U.S. dollars on the London market. SOURCES: Reserves are from the IMFs International Financial Statistics, line 1ds; nominal GDP (world) and real GDP (world) are from the World Bank online database, World Databank; commodities, commodities excluding gold and energy, and energy are from the European Central Bank database. The price of gold is from the IMFs International Financial Statistics.

488

Bretton Woods

Transmission Channels

There are several channels through which an increase in liquidity may be associated with a rise in asset prices. First, an increase in liquidity tends to boost the demand for assetssuch as government bonds, equities, commodity-indexed securities, and real estate increasing their prices and reducing their rates of return (Baks and Kramer 1999: 5). If inflation in goods-and-services prices is relatively low because of, for example, productivity growth, the prices of assets will rise in real terms (IMF 2000: 8889). Second, according to the Austrian view of financial crises, a rise in asset prices, whatever the cause, can lead to a bubble if monetary policy passively allows bank credit to expand, fueling the boom (Bordo and Wheelock 2004: 20). The Austrian view associates rising asset prices and financial imbalances (including current-account imbalances) with general inflation regardless of developments in the prices of goods and services (see Borio and White 2003). Third, in the specific case of commodities, economies that maintain undervalued exchange rates to boost growth contribute to a price spike in two ways: (1) the increase in the demand for commodities as inputs into production leads to higher prices of commodities, other things being the same; and (2) the initial price increases can lead to expectations of further increases, making investments in commodities more attractive.

Ending the Link between the Dollar and Gold

During most of the BWI period, discipline on the United States the main supplier of global liquiditywas imposed in two ways. First, the United States pegged the price of the dollar at $35 per ounce of gold. Second, it maintained the convertibility of the dollar into gold at that fixed price. If U.S. policies were overly expansionary, the resulting balance-of-payment deficits were paid for by sending dollars abroad. Foreign central banks were permitted to exchange those dollars for gold at the U.S. Treasury, imposing some discipline over U.S. policies. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, several events transformed the Bretton Woods regime from one based on the convertibility of the U.S. dollar into gold (at a fixed price) to one based on fiat money. In this connection, prior to 1958, less than 10 percent of cumulative U.S. balance-of-payments deficits since the end of World War II had been financed through U.S. gold sales; from 1959 until 1968 almost

489

Cato Journal

67 percent of the U.S. cumulative balance-of-payments deficits were financed from U.S. gold reserves (Cohen 2001: 6). When the Bretton Woods regime started, the United States held about 75 percent of the worlds monetary stock (Meltzer 1991: 56); by 1968, the U.S. share had declined to about 25 percent. To preserve its remaining gold stock, the U.S. took the following measures to sever the link between the dollar and gold: In March 1968, a run on sterling and the dollar into gold brought a collapse of the gold pool agreement that was initiated in 1961 by Belgium, France, Federal Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States to stabilize the price of gold at $35 an ounce on the London market (the main trading center for gold). The gold pool became a key pillar of the Bretton Woods I regime (Yeager 1976: 42527; Eichengreen 2007: chap. 2). With the abandonment of the gold pool, the price of gold for official transactions remained at $35 per ounce, but the members of the gold pool did not attempt to control the price of gold in private transactions. In order to prevent arbitrage between the private and official markets for gold, central banks agreed not to sell in the private gold market (Meltzer 1991: 63). In March 1968, the Federal Reserve removed the 25 percent gold backing requirement for the issuance of Federal Reserve notes. As Bordo (1993: 7072) argued, The key effect of these [two] arrangements was that gold was demonetized at the margin. . . . In effect, the world switched to a de facto dollar standard.2 Following a sharp rise in the U.S. balance-of-payments deficit in the first quarter of 1971 and a run against the U.S. dollar, President Richard Nixon ended U.S. gold outflows in August 1971 by announcing that the United States would no longer sell gold to foreign central banks. That action severed the remaining link between the dollar and gold.3

2 Similarly, Yeager (1976: 575) argued that with convertibility at an end, the world was on a de facto dollar standard rather than a genuine gold-exchange standard. 3 Nixon announced that the suspension of convertibility would be temporary. At the Smithsonian Agreement of December 1971, gold was repriced at $38 per ounce but the dollar remained de facto inconvertible. Meltzer (1991: 80) observed that the action by the U.S. government in August 1971 formalized the restriction that had been in effect for more than three years by refusing to sell gold.

490

Bretton Woods

Why did the United States sever the links between the dollar and gold during the late 1960s and early 1970s? Beginning in the early 1960s, the Federal Reserve implemented expansionary monetary policies, which led to rising inflation, declining competitiveness, and growing balance-of-payments deficits (Meltzer 1991, Bordo 1993); the Federal Reserve concentrated almost excessively on domestic objectives (Meltzer 1991: 79). As foreign central banks accumulated U.S. dollar reserves, the United States came under the threat of a convertibility crisis. To address that threat, the U.S. government and the Fed severed all links between the dollar and gold. However, those actions transformed the international monetary system from a commoditybased system to a fiat-money system. The Bretton Woods regime was set adrift without an anchor.4 As a result, growth of global liquidity exploded in the early 1970s and, in early 1973, the old regime collapsed, ushering in a new regime of managed floating exchange rates. With the recent re-emergence of a large periphery that maintains pegged, undervalued exchange rates against the dollar, the conditions that led to the breakdown of the earlier Bretton Woods regime have been reintroduced. We do not want to push the Bretton Woods metaphor too far. Clearly, many major currencies, including the euro, float against the dollar, and some Asian emerging market economies do not follow tight pegs. Nevertheless, to the extent that a large and rising share of U.S. external trade is conducted under fixed rates within a pure fiat money regime, there are some striking similarities between the Bretton Woods system of the early 1970s and the regime that emerged in the 2000s.

The Global Financial System, 200307

The salient characteristics of the global financial system in the five years ending in 2007 are reminiscent of the 197074 Bretton Woods system: During 200307, there were sharp rises in global liquidity and commodity prices; U.S. share prices and real estate prices boomed.

4 Meltzer (1991: 82) noted that discipline [on the Federal Reserve] was lacking once the de facto embargo on gold was in place after March 1968. Meltzer also pointed out that some of the responsibility for the breakdown of the earlier Bretton Woods regime lay with the periphery countries, which made few efforts to adjust their policies. Bordo (1993: 73) argued: Without gold convertibility, there was no commitment mechanism to constrain the United States to follow a stable monetary policy.

491

Cato Journal

U.S. current-account deficits averaged about 5.5 percent of GDP (Table 2), compared with about 1.5 percent in the preceding 30 years. Measured in terms of Special Drawing Rights, the cumulative total of the U.S. current-account deficits amounted to 2.68 trillion SDRs (Table 2). The increase in global liquidity during the same period was 2.43 trillion SDRs. Seven Asian emerging market economieseconomies that form the core of the new peripheryaccounted for more than 45 percent of the rise in global liquidity (Table 2). U.S. interest rates were at very low levels for much of the period. The relationship among these characteristics is marked by interconnected feedback loops. Consider the following: The exchange rate policy of the Asian periphery, under which the periphery accumulated reserves and invested in U.S. financial assets, pushed up the prices of those assets and decreased U.S. interest rates. The exchange rate policy of the periphery led to higher growth in the countries concerned, underpinned by exports, increasing the demand for commodities as inputs into production, pushing up the prices of those inputs. In turn, the price rises made commodities more attractive as investment vehicles. Higher commodity prices widened the U.S. current-account deficits. They also widened the current-account surpluses of commodity exporters, including oil exporters, many of which maintain dollar pegs. Those surpluses resulted in higher global reserves and lower U.S. interest rates. Low U.S. interest rates contributed to higher U.S. domestic demand, increasing the current-account deficit and contributing to higher U.S. asset prices. Higher U.S. asset prices led, through wealth and balance-sheet effects, to an increase in U.S. economic growth, raising the current-account deficit and pushing up asset prices further. There are other feedback loops, but we think our point is clear: the current BWII system, like the waning years of the BWI regime lacks the discipline of dollar convertibility into gold. Without a credible anchor, the global monetary system is prone to crises.

492

TABLE 2 Current Account Balances and International Reserves, 200307

Change in Reserves

United States Current Account

Year 60.6 121.0 179.1 135.5 258.1 754.1 12.3 120.1 77.7 35.6 2.7 0.1 7.4 1.6 6.1 16.8 14.9 11.7 21.2 55.5 16.2 23.8 19.0 11.6 7.1 5.0 12.9 6.5 5.9 9.3

Percent Amount GDP (billions of SDRs) China Hong Kong India Korea

World

Total of Seven Asian Malaysia Singapore Taiwan Economies 4.3 7.7 8.8 9.3 12.5 42.8 20.1 16.7 21.5 1.0 6.8 50.5 1,093.1

2003 4.7 2004 5.3 2005 5.9 2006 6.0 2007 5.2 Cumulative Balance

372.4 426.2 506.8 546.2 474.7

265.5 377.5 581.2 455.4 745.1

2,680.8

2,424.6

SOURCE: International Monetary Fund, International Monetary Statistics.

Bretton Woods

493

Cato Journal

Conclusion

Under the early Bretton Woods regime, the United States had a formal obligation to link the dollar to gold. That system broke down in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Under the new Bretton Woods system from 200307, the Federal Reserve delivered low inflation, but its monetary policy took essentially no account of external factors and the implications of its policy stance for global liquidity creation, while the peripheryin particular, emerging market economies in Asia, especially Chinapegged their currencies to the dollar at artificially low levels to promote exports. Like the BWI system from 197073, the new Bretton Woods regime is conducive to large U.S. current-account deficits, high global liquidity creation, and asset price bubbles.5 The crisis that erupted in August 2007 led to a sharp contraction in U.S. growth, bringing down the U.S. current-account deficit. Yet, to the extent that the revived Bretton Woods regime was one of the main reasons for the crisis, the underpinnings of the next crisis are in place. In a world comprised of fiat currencies and a large powerful center country whose central bank operates in the absence of a convertibility principle linking the dollar to gold, floating exchange rates among all the major currency areas, including the countries of the periphery, would provide a mechanism for the adjustment of global imbalances and a safeguard against a future crisis.

References

Baks, K., and Kramer, C. (1999) Global Liquidity and Asset Prices: Measurement, Implications and Spillovers. International Monetary Fund Working Paper No. 168 (December). Bordo, M. (1993) The Bretton Woods International Monetary System: A Historical Overview. In M. Bordo and B. Eichengreen (eds.) A Retrospective on the Bretton Woods System, 3108. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Bordo M., and Wheelock, D. (2004) Monetary Policy and Asset Prices: A look Back at Past U. S. Stock Market Booms. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 86 (November/December): 1944.

5

A formalization of the above argument is provided in Dellas and Tavlas (2011).

494

Bretton Woods

Borio C., and White, W. (2003) Whither Monetary and Financial Stability? The Implication of Evolving Policy Regimes. Paper presented at Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Symposium on Monetary Policy and Uncertainty: Adapting to a Changing Economy, Jackson Hole, Wyo. (August). Cohen, B. J. (2001) Bretton Woods System. In R. J. B Jones (ed.) Routledge Encyclopedia of International Political Economy. London: Routledge. Dellas, H., and Tavlas, G. S. (2011) Exchange Rate Regimes and Asset Prices. Unpublished manuscript. Dooley, M. P.; Folkerts-Landau, D.; and Garber, P. M. (2003) An Essay on the Revived Bretton Woods System. NBER Working Paper No. 9971. (2004a) The Revived Bretton Woods System. International Journal of Finance and Economics 9: 30713. (2004b) Direct Investment, Rising Real Wages and the Absorption of Excess Labor in the Periphery. NBER Working Paper No. 10626. (2005) Saving Gluts and Interest Rates: The Missing Link to Europe. NBER Working Paper No. 11520. (2006) Interest Rates, Exchange Rates and International Adjustment. Paper presented at the 51st Economic Conference of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. (2009) Bretton Woods II Still Defines the International Monetary System. NBER Working Paper No. 14731. Eichengreen, B. (2007) Global Imbalances and the Lessons of Bretton Woods. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. International Monetary Fund (2000) Asset Prices and the Business Cycle. World Economic Outlook. Washington: IMF (May). Meltzer, A. (1991) U.S. Policy in the Bretton Woods Era. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 73: 5483. Yeager, L. B. (1976) International Monetary Relations: Theory, History, and Policy. 2nd ed. New York: Harper & Row.

495

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Network PlanningDocument59 pagesNetwork PlanningVignesh ManickamNo ratings yet

- IE Singapore MRA GrantDocument4 pagesIE Singapore MRA GrantAlfizanNo ratings yet

- Barkley Rosser Microfoundations Reconsidered Book ReviewDocument6 pagesBarkley Rosser Microfoundations Reconsidered Book ReviewEleutheros1No ratings yet

- Alesina and Tabellini On External DebtDocument37 pagesAlesina and Tabellini On External DebtEleutheros1No ratings yet

- Morrow Carter Left, Right Left. Income Learning and Political DynamicsDocument34 pagesMorrow Carter Left, Right Left. Income Learning and Political DynamicsEleutheros1No ratings yet

- Austerity in The Eurozone: Impact AssessmentDocument18 pagesAusterity in The Eurozone: Impact AssessmentmschotoNo ratings yet

- De Vroey The History of Macroeconomics From Keynes's General Theory To The PresentDocument28 pagesDe Vroey The History of Macroeconomics From Keynes's General Theory To The PresentEleutheros1No ratings yet

- Hoover Mathematical Economics Comes To AmericaDocument47 pagesHoover Mathematical Economics Comes To AmericaEleutheros1No ratings yet

- Bernholz Property Rights, Contracts, Cyclical Social Preferences and The Coase Theorem A SynthesisDocument24 pagesBernholz Property Rights, Contracts, Cyclical Social Preferences and The Coase Theorem A SynthesisEleutheros1No ratings yet

- Bernholz Supreme Values As The Basis For TerrorDocument17 pagesBernholz Supreme Values As The Basis For TerrorEleutheros1No ratings yet

- De Grauwe Self-Fulfilling Crises in EurozoneDocument22 pagesDe Grauwe Self-Fulfilling Crises in EurozoneEleutheros1No ratings yet

- Weintraub The Macrofoundations of MacroeconomicsDocument23 pagesWeintraub The Macrofoundations of MacroeconomicsEleutheros1No ratings yet

- Aizenman Credit Ratings and The Pricing of Sovereign Debt During The Euro CrisisDocument31 pagesAizenman Credit Ratings and The Pricing of Sovereign Debt During The Euro CrisisEleutheros1No ratings yet

- Bernholz Genralized Coase TheoremDocument5 pagesBernholz Genralized Coase TheoremEleutheros1No ratings yet

- Boettke Sautet The Genius of Mises and The Brilliance of KirznerDocument16 pagesBoettke Sautet The Genius of Mises and The Brilliance of KirznerEleutheros1No ratings yet

- De Jasay The Charms of Deferred CostDocument5 pagesDe Jasay The Charms of Deferred CostEleutheros1No ratings yet

- Holcombe & Gwartney Unions Economic Activity and GrowthDocument22 pagesHolcombe & Gwartney Unions Economic Activity and GrowthEleutheros1No ratings yet

- Rappaport The Modal View of Economic ModelsDocument20 pagesRappaport The Modal View of Economic ModelsEleutheros1No ratings yet

- Dellas Tavlas The Fatal Flaw The Revived Bretton-Woods System, Liquidity Creation, and Commodity-Price BubblesDocument20 pagesDellas Tavlas The Fatal Flaw The Revived Bretton-Woods System, Liquidity Creation, and Commodity-Price BubblesEleutheros1No ratings yet

- Salin Cartels As Efficient Productive StructuresDocument14 pagesSalin Cartels As Efficient Productive StructuresEleutheros1No ratings yet

- Woodford Macroeconomic Analysis Without The Rational Expectations HypothesisDocument82 pagesWoodford Macroeconomic Analysis Without The Rational Expectations HypothesisEleutheros1No ratings yet

- Rappaport Economic Models As Mini-TheoriesDocument16 pagesRappaport Economic Models As Mini-TheoriesEleutheros1No ratings yet

- Rappaport The As-If View of Economic Motivational HypothesisDocument21 pagesRappaport The As-If View of Economic Motivational HypothesisEleutheros1No ratings yet

- Tavlas Hall Gibson The Greek Financial Crisis Growing Imbalances and Sovereign SpreadsDocument42 pagesTavlas Hall Gibson The Greek Financial Crisis Growing Imbalances and Sovereign SpreadsEleutheros1No ratings yet

- Lorenzoni Slow Moving Debt CrisesDocument33 pagesLorenzoni Slow Moving Debt CrisesEleutheros1No ratings yet

- Block and Barnett Mainstream Economics Is Not ScientificDocument13 pagesBlock and Barnett Mainstream Economics Is Not ScientificEleutheros1No ratings yet

- Woodford Interest and Prices ErrataDocument9 pagesWoodford Interest and Prices ErrataEleutheros1No ratings yet

- Woodford Convergence in MacroeconomicsDocument24 pagesWoodford Convergence in MacroeconomicsEleutheros1No ratings yet

- Woodford Fiscal Requirements of Price StabilityDocument61 pagesWoodford Fiscal Requirements of Price StabilityEleutheros1No ratings yet

- Europe's Debt Crisis, Coordination Failure, and International EffectsDocument38 pagesEurope's Debt Crisis, Coordination Failure, and International EffectsADBI PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Cettolin Justice Under UncertaintyDocument44 pagesCettolin Justice Under UncertaintyEleutheros1No ratings yet

- Indian Economy Classified by 3 Main Sectors: Primary, Secondary and TertiaryDocument5 pagesIndian Economy Classified by 3 Main Sectors: Primary, Secondary and TertiaryRounak BasuNo ratings yet

- (Topic 6) Decision TreeDocument2 pages(Topic 6) Decision TreePusat Tuisyen MahajayaNo ratings yet

- Indonesian Maritime Logistics Reforms Support Early ImpactsDocument8 pagesIndonesian Maritime Logistics Reforms Support Early ImpactsOctadian PNo ratings yet

- Tony Tan Caktiong – Jollibee founderDocument6 pagesTony Tan Caktiong – Jollibee founderRose Ann0% (1)

- 17FG0045 BoqDocument2 pages17FG0045 BoqrrpenolioNo ratings yet

- Econ 002 - INTRO MACRO - Prof. Luca Bossi - February 12, 2014 Midterm #1 SolutionsDocument9 pagesEcon 002 - INTRO MACRO - Prof. Luca Bossi - February 12, 2014 Midterm #1 SolutionsinmaaNo ratings yet

- Organic Chicken Business RisksDocument13 pagesOrganic Chicken Business RisksUsman KhanNo ratings yet

- 2010 Tax Matrix - Individual AliensDocument2 pages2010 Tax Matrix - Individual Alienscmv mendozaNo ratings yet

- Peraturan Presiden Nomor 16 Tahun 2018 - 1001 - 1Document174 pagesPeraturan Presiden Nomor 16 Tahun 2018 - 1001 - 1Bambang ParikesitNo ratings yet

- Fair & Lovely Born: 1978 History: The Fairness Cream Brand Was Developed by Hindustan Lever LTDDocument3 pagesFair & Lovely Born: 1978 History: The Fairness Cream Brand Was Developed by Hindustan Lever LTDNarendra KumarNo ratings yet

- CH 15 CDocument1 pageCH 15 CstillnotbeaNo ratings yet

- Global Trends AssignmentDocument9 pagesGlobal Trends Assignmentjan yeabuki100% (2)

- RubricsDocument2 pagesRubricsScarlette Beauty EnriquezNo ratings yet

- Cloud Family PAMM IB PlanDocument4 pagesCloud Family PAMM IB Plantrevorsum123No ratings yet

- Vietnam Trade MissionDocument2 pagesVietnam Trade MissionXuân NguyễnNo ratings yet

- What is Economics? - The study of production, distribution and consumption /TITLEDocument37 pagesWhat is Economics? - The study of production, distribution and consumption /TITLEparthNo ratings yet

- Company Scrip Code: 533033Document17 pagesCompany Scrip Code: 533033Lazy SoldierNo ratings yet

- BELENDocument22 pagesBELENLuzbe BelenNo ratings yet

- Why education and facilities are better than laws for increasing home recyclingDocument1 pageWhy education and facilities are better than laws for increasing home recyclingFadli AlimNo ratings yet

- Elasticity of SupplyDocument11 pagesElasticity of Supply201222070% (1)

- Application For Leave: Salawag National High SchoolDocument3 pagesApplication For Leave: Salawag National High Schooldianna rose leonidasNo ratings yet

- Weekly business quiz roundup from 2011Document8 pagesWeekly business quiz roundup from 2011Muthu KumarNo ratings yet

- B.Satyanarayana Rao: PPT ON Agricultural Income in Indian Income Tax Act 1961Document17 pagesB.Satyanarayana Rao: PPT ON Agricultural Income in Indian Income Tax Act 1961EricKenNo ratings yet

- E Tiket Batik Air MR Yoga Dwinanda Wiandri CGK-KOE KOE-HLPDocument3 pagesE Tiket Batik Air MR Yoga Dwinanda Wiandri CGK-KOE KOE-HLPyayat boerNo ratings yet

- IntroductionDocument3 pagesIntroductionHîmäñshû ThãkráñNo ratings yet

- A Presentation ON Amul DairyDocument12 pagesA Presentation ON Amul DairyChirag PanchalNo ratings yet

- Product Data Mtu Kinetic PowerPackDocument9 pagesProduct Data Mtu Kinetic PowerPackEhab AllazyNo ratings yet

- OCI DiscussionDocument6 pagesOCI DiscussionMichelle VinoyaNo ratings yet