Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hospitality and The Fashion

Uploaded by

Raven BlackOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Hospitality and The Fashion

Uploaded by

Raven BlackCopyright:

Available Formats

I n t e r n a t i o n a l

J o u r n a l

o f

M a n a g e m e n t

C a s es

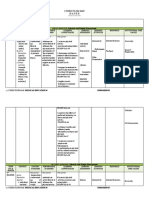

HOSPITALITY AND THE FASHION INDUSTRY: THE MISSONI WAY

Alice Dallabona Nottingham Trent University, UK

Abstract The aim of this paper is to investigate brand extension within the Italian luxury fashion industry, specifically the launch of new ventures which seek to expand the visibility of the labels by creating new spaces like hotels, bars and restaurants. These spaces offer the opportunity to experience a particular lifestyle, often in strict alignment with the philosophy of the brand and its country of origin. I will focus on the case of the Missoni Hotel in Edinburgh and investigate the narratives implied by the various elements that characterise it, including architecture, interior design and gastronomy, in order to explore how they work together in creating a sense of Italianicity strictly related to the concept of hospitableness. Moreover the paper aims to explore how these different narratives relate to the identity of the brand, in order to underline situations of dialogue or contradiction. The research is based on the analysis of qualitative data through a multidisciplinary methodology, where semiotic theories are assigned a privileged position. This paper aims to show how both the Italian lifestyle and the prestige of Italian fashion industry constitute important elements of cultural heritage that can be productively employed in the fields of leisure and hospitality marketing. KEYWORDS: Branding, Italianicity, Hospitality, Lifestyle, Fashion.

relationship with the philosophy of the brand. This paper aims to investigate the case of the brand Missoni Hotel, referring in particular to its first development in Edinburgh, that constitutes the entrance of the luxury fashion brand Missoni S.p.A. in the hospitality business. The result is the creation of a lifestyle brand that focus on all the objects and services people use every day (Chevalier and Mazzalovo, 2008: 133) and that proposes the home lines related to Missoni S.p.A., like home furnishing accessories, interior decoration items and tableware, as well as other services such as restaurants and bars. This study aims to contribute to the understanding of the expanding phenomenon of Italian luxury fashion labels entering into the hospitality and leisure business, by analysing it from a semiotic point of view and by exploring how Italianicity and Italian lifestyle can constitute important elements of cultural heritage that can be productively employed in these fields. In the next few pages I aim to investigate the interlocking narratives that hold between the different elements that characterise the space of the Missoni Hotel Edinburgh (i.e. architecture, interior design and gastronomy). Firstly, it will be explored the relationship between these elements and the identity of the mother brand they refer to (Missoni S.p.A.) in order to emphasise situations of dialogue and contradiction. Secondly, the narratives will be considered in relation to Italy and its cultural heritage, as signifiers that contribute to create a sense of Italianicity. This is a key term in my research, a neologism created by semiologist Roland Barthes adding the suffix -icity to the adjective Italian in order to produce a noun that should be primarily connoted as abstract. Barthes defined Italianicity as not being equal to Italy, as it is in fact the condensed essence of everything that could be Italian, from spaghetti to painting (Barthes, 1977: 48). In this sense, Italianicity, is much more appropriate than the word Italianness

Introduction

In the last few years, many Italian luxury fashion labels have launched, or plan to launch, new ventures in order to expand their recognizability outside the usual area of accessories and cosmetics, by creating new spaces such as bars, restaurants and hotels, where people can experience a particular lifestyle, often in strict

439

Internation a l

J o u r n a l

o f

M a n a g e m e n t

C a s e s

in order to describe the phenomena I am analysing, precisely because of this peculiar characteristic of the term, that does not aim to sclerose into a definitive list of elements that are Italian tout court but remains open to new additions that, case by case, are linked to Italy and its lifestyle. The case of the Missoni Hotel in Edinburgh is particularly interesting because the fashion label Missoni has been described by Chevalier and Mazzalovo (2008) as a brand that might face difficulties in diversifying its portfolio of products. Firstly because Missoni was not originally founded on a lifestyle, unlike Ralph Lauren and its New England WASP allure for example. Secondly, because Missoni established its identity on a specific type of fabric and a specific chromatic palette that are considered as problematic in terms of extensions besides the realms of clothing and accessories (Chevalier and Mazzalovo, 2008: 133). However, I shall argue that the elements mentioned above can productively be employed in a lifestyle brand and actually have been incorporated and constitute the core of the identity of the Missoni Hotel brand. Moreover it will be observed that such elements, which feature in the space of the Edinburgh hotel and that are strongly linked to Missonis identity, work as signs of the fashion label and create effects of presence strictly related to the figure of the designer, a mythical figure that constitutes the core of many Italian luxury fashion houses. In particular, it will be argued that the strong host figures evoked by the space and services of the Missoni Hotel Edinburgh, that concur in establishing almost a personal relationship between them and the hotels customer, appear to blur the distinction between hospitability and hospitableness, that is so central for the definition of the hospitality business. Discussing the lack of a universally shared definition of the term hospitality Brotherton proposes a distinction between that and the term hospitableness, a distinction that proves to be rather relevant for the present work. Brotherton defines hospitality as a contemporaneous human exchange, which is voluntarily entered into, and designed to enhance the mutual wellbeing of the parties concerned through the provision of accommodation and food or drink (Brotherton, 1999:168) and aims to show how that transcends hospitableness. In fact hospitable behaviour is not central for the definition of hospitality, as it can be displayed in different situations and, more

importantly, hospitality is invariably designed to make guests feel as though they were not at home, and is desired for this very aspect (Brotherton, 1999:167). In this respect, he claims, hospitality goes beyond the need to make guests feel at home, an element that he considers instead to belong to the realm of hospitableness, and finds in that very characteristic its reason of being. In the space of the Hotel Missoni Edinburgh, however, this distinction appears to be somehow blurred. In fact, as it will be argued later, elements that remind of hospitableness are also present. In the semiotic analysis of the spaces it will be observed how they feature connotations of cosyness and homeliness and strong references to ideal host figures in the form of the Missonis, displayed in different ways, therefore creating a space that actually features homely connotations. However the sense of home that the space of the Hotel Missoni Edinburgh creates is something different from any domesticity that guests might have experienced, remaining an other place that refers to a concept of homeliness and hospitableness that is intrinsically linked to the Missonis identity and that relies heavily on Italy and its cultural heritage.

Missoni S.p.A

Missoni S.p.A is a privately owned Italian luxury fashion label whose history began in 1958, making the company one of the oldest firms among its direct competitors (Okonkwo, 2007: 47). The core of the label is constituted by Ottavio Missoni and his wife Rosita Jelmini, and their personalities have played a very important role in the characterisation of the company, that is still evident today. However, the younger members of the family have been gradually involved in the family business and now hold very important roles in the business. Family has always been a big part of Missonis identity, and members have not only always contributed to the various aspects of the business, but also featured in advertisements on several occasions, as discussed later. Knitwear is another very important part of the Missonis identity, in fact the label is renowned for its extremely lightweight pieces and the brightly coloured patterns, that constitute iconic and distinctive features of the label (Casadio 1997, 119-120). The fashion label is well established abroad: the first Missoni boutique opened in 1970 in the prestigious U.S. department store Bloomingdales, and played a very important

440

I n t e r n a t i o n a l

J o u r n a l

o f

M a n a g e m e n t

C a s es

role in the creation of the fame of Italian design (Casadio, 1997: 120). Anticipating the trend of brand expansion in the fields of home collections and lifestyle products, in the Seventies Missoni launched its first collection of household linens and shortly after that a line of furnishing fabrics. From this core, in 1983, the MissoniHome collection developed, significantly produced by T&J Vestor, the company of Rosita Missonis family. In 2005 Missoni S.p.A. signed a worldwide license agreement with Redizor Hotel Group, an hotel management company, for the development of a new lifestyle hotel brand, called Hotel Missoni. The first installment opened in Edinburgh in 2009 and future hotels are set to open in Kuwait, Oman and Brazil in the next two years.

Semiotics and brands

Through the years, semiotics have dedicated more and more attention to issues related to brands and their identity, focusing on the different aspects of their manifestation. From the seminal work of Roland Barthes (1977), the incursions of semiotics into this area have become more frequent and consistent, creating theories and tools that aim to make sense of the phenomenon of branding in its complexity, considering the brands communication, its manifestations and issues related to its identity (see Mick at al 2004). A vast corpus of research exists on advertising (see for example Semprini 1997, Bianchi 2005, Donatone 2007, Arning 2009, Imperi 2010 to name just a few) but works have also been produced on the phenomena of brand and branding, leading to the development of a series of models and tools that can be productively employed in other disciplines, such as marketing for example (see Chevalier and Mazzalovo 2008). In particular, semiotics can support a manager in defining, prolonging and defending the identity of a luxury brand (Chevalier and Mazzalovo, 2008: 190) through the introduction of some powerful semiotic instruments, including a special version of the semiotic square and semiotic mapping. The former was developed by Jean-Marie Floch, who was the first to ever apply semiotics to marketing and published a series of studies that prove to be still very useful nowadays (see Floch 1988, 1990 and 1995). Flochs semiotic square, in particular, is an instrument developed for the analysis of

advertisements that articulates on the semiotic square two opposite categories of values (for a more detailed discussion of the original semiotic square see Greimas and Courts 1979 but also Marsciani and Zinna 1991 and Magli 2004). These different categories originate in the fact that a subject can valorise an object according to the logic of utopian or practical values. The former are perceived as being important for the very existence of the subject that longs for being united to them, while the latter imply that the object is relevant just for its practical use. Floch articulates these two categories of values and identifies four types of valorisation (practical, ludic, critical and utopian) that can be present in advertising campaigns (see Floch 1990 but also Marrone 2001 and Marrone 2007). Another very important figure in this respect is Andrea Semprini, whose approach is sociosemiotic and focuses more in depth on issues related to contemporary brands (see Semprini 1993, 1996, 2003 and 2006). He reprised Flochs semiotic square and developed it further, creating a four quadrant model, called semiotic mapping, that makes sense of the subtle differences between the values mentioned above and on which brands can be positioned and compared (see Semprini 1993 and Marrone 2007). However, there are other semioticians that have investigated issues related to brands and marketing, such as Gianfranco Marrone and Giulia Ceriani (see Marrone 2001 and 2007 and Ceriani 2001, but also Lombardi 2000 and Semprini 2003 for example), constituting an additional theoretical heritage that can complement different approaches and that can be productively applied in other disciplines.

The Case Study

The object of my analysis is Hotel Missoni Edinburgh, the first development of a series of hotels that are set to open in Kuwait, Oman and Brazil respectively in 2011 and 2012. The Hotel Missoni brand belongs to the Rezidor Hotel Group, a hospitality management company based in Brussels that has a portfolio of more than 400 hotels worldwide. In 2005 Rezidor signed a worldwide license agreement with Italian fashion label Missoni S.p.A. in order to develop and manage a new brand of luxury lifestyle hotels and in June 2009 the first of these opened under the name Hotel Missoni Edinburgh (see Rezidor Fact Sheet 2010).

441

Internation a l

J o u r n a l

o f

M a n a g e m e n t

C a s e s

Missoni Hotel Edinburgh occupies most of a building designed by Allan Murray Architects practice, based in Edinburgh, and that features also a bank and a retail space. The interior design was provided by Italian Matteo Thun, in close relationship with Rosita Missoni. The hotel has been recently awarded a five star rating and features 136 rooms (of which seven are suites) a gym and hosts events facilities which include the Nero Bianco events room, a lounge, a boardroom and a private dining room. A spa is currently under development. The hotel is in a central location in Edinburghs Old Town, very close to the famous Royal Mile. In this respect, the hotels seems to respond to the criteria that rule flagship stores development, which is aimed to reinforce the prestige of the brand through its up-market location (Moore, 2000: 273) and that serve as a promotional device to showcase the brand in a coherent and closely managed setting, and encourage brand awareness and interest (Moore, 2000: 272). The similarities between flagship stores and the hotel do not end here, as if the store is a metaphor for the brand (Moore, 2000: 272) so is the hotel. In this sense, the Missoni Hotel Edinburgh is a metaphor for the fashion label Missoni S.p.A., that constitutes the origins of the Missoni Hotel brand. The present work will focus on the characteristics of Hotel Missoni Edinburgh considering them firstly in relation with the identity of the mother brand Missoni S.p.A., in order to identify situations of dialogue or contradiction, and secondly in relation to Italy and its cultural heritage. The next paragraphs will be dedicated to the first topic mentioned above, the analysis of the relationship that Missoni Hotel Edinburgh holds with the mother brand Missoni S.p.A. and its identity. The Hotel Missoni brand originates from and depends on the identity of the Missoni fashion label, but at the same time translates the latter into spaces and services that transcend the mother companys identity. In this case Missoni S.p.A. provides not only the distinctive features, the look, of the hotel but also a certain authority behind it, that acts as a sort of sender-judge in the Greimasian sense, as it both creates and sanctions the identity of the hotel (for a more detailed discussion of the actantial model see Greimas 1966 but also Marsciani and Zinna 1991 and Magli 2004). This phenomenon is evident in the brochure of the Edinburgh hotel, where its value is presented as being related to the fashion label and to being a true representation of

it, so that Missoni S.p.A. does not only provide a means for the Missoni Hotel to differentiate itself but constitutes the source of its identity and also sanctions it. In this sense, Missoni S.p.A. constitutes a form of authority that creates and enhances the prestige and the status of the hotel itself, and for this reason is strongly present in every aspect of the hotel, creating a strong presence effect through a variety of ways. In fact we can identify three forms of presence of the fashion label Missoni in the Hotel Missoni Edinburgh. Firstly, it is evident in the very logo of the hotel, written in stone on its faade, which is clearly derived from the one of the fashion brand. The Missoni Hotel logo in fact replicates identically the logo of Missoni S.p.A. and maximises it in order to create a superlogo, constituted by several logos of the fashion company. However the use of the logo and name Missoni is not the only way the fashion company is present in the space of the hotel, in fact this verbal message is reinforced through a series of objects such as sofas and carpets. Secondly there is in fact a significant presence of typically Missoni patterns, especially the colourful zig-zag and the stripes that feature on carpets, sofas, towels and bathrobes, but also in less expected places. In fact the very first member of staff that clients encounter at the hotel is a man wearing a kilt, the traditional Scottish garment, that presents a typically Missoni zig-zag pattern and not a traditional tartan one. These patterns are so closely related to the Missoni S.p.A. brand and its identity that can substitute it by metonymy, because the process of identification between them is so established that the fashion label can be represented by one of its smallest parts, in this case the patterns (see Barthes, 1977: 50). These patterns work as signs of the brand Missoni S.p.A. and concur in creating an effect of presence so that the place speaks both of the Missoni brand and the Missoni family without even having to name or show them. In fact the Missonis are very much present in other forms, and primarily through their activity, as visible in the lobby area which features columns and small coffee tables that resemble reels of thread. These elements refer to the traditional strong association between the Missoni label and knitwear, that still characterise the identity of the label nowadays. Indeed it was the work of fashion house Missoni that constituted the base for the worldwide reputation of Italian fashion for knitwear (Steele, 2003: 51). Moreover, the reels of thread

442

I n t e r n a t i o n a l

J o u r n a l

o f

M a n a g e m e n t

C a s es

feature typically Missoni stripy patterns, therefore reinforcing once again a sort of Missonification, i.e. the process of becoming Missoni, of the space. Finally, there is a much more personal form of presence of the fashion label Missoni in the space of the Hotel Missoni Edinburgh, consisting in photographs of its founder Ottavio Missoni. This presence is a very limited one as it consists in just a few pictures, placed in the gym, that show Ottavios sport career as a runner in the Forties. However, it is mostly the redundancy of signs that refer to typical Missoni patterns and their production that create the Missonification of the space of the hotel and constitute a fil rouge throughout. This is possible to see from the fact that the only place where they are absent, in the gym, more explicit elements are featured, in the form of Ottavios pictures. They feature, however, quite organically and not constitute a totally arbitrary addition in the gym, as they are sport related. This is coherent with a strategy of rationing the physical presence of the Missonis and limiting it to few elements in order to create a space that refers primarily to Missoni fashion but that also evokes its creators, although mostly through references to their production and just marginally through photographs. However, this does not lessen the personalisation of the space of the hotel, that aims to make the guests to feel part of the Missoni family and somehow at home. This is a strategy that focuses on ideas of authenticity and a sense of place, and that has been employed by several fashion brands that have strong family roots and close relations with their area of provenance (see Chevalier and Mazzalovo, 2008: 133). De facto, the Missoni family is not significantly featured in the space of the Missoni Hotel Edinburgh, a choice that might appear in contrast with the advertising strategy that Missoni S.p.A. has employed over the years. In fact the family has always been a big part of Missonis identity, with members contributing to various aspects of the business, and has featured in advertising campaigns in several occasions, like the 1992 photographic campaign by Oliviero Toscani and, more recently, the fall/winter 2010 campaign by Kenneth Anger. In this respect, however, it is possible to see that Missoni Hotel brand does not focus primarily on the widely recognised identification between Missoni S.p.A. and the Missoni family but on the material characteristics of the brands, like its strong association with certain patterns and the important role of knitwear, as reminded also by several piece

of art scattered over the hotel. However the choice to avoid images of the Missonis does not result in their annihilation in the spaces of the hotel, not only because it ultimately represents their style but also because it features services that are inspired by their public persona and by the elements that characterise their philosophy, that is strongly intertwined with Italy and its lifestyle. In fact Hotel Missoni Edinburgh talks of the Missonis, alludes to them through their work and the references to its production, evokes them as simulacra of hosts and aims to translate the characteristics that are commonly associated with them, like dedication to family and joie de vivre (see Casadio, 1997) into spaces and services that are totally new and unexplored for the fashion label. In this respect, the cases of the lobby and the restaurant of Missoni Hotel Edinburgh are the epitomes of this phenomenon.

A semiotic analysis of the spatial articulation

The following semiotic analysis of the spatial articulation of the lobby is going to show in detail how it can carry values and concur to the creation of the peculiar identity of Missoni Hotel Edinburgh through elements that refer to and are coherent with the characteristics mentioned above, i.e. a Missonification of the space created with the display of the company logo, its typical patterns and references to the Missoni family. The lobby consists of an open space that comprises reception, bar and restaurant spread over two levels, visible from outside through large glass walls. It has been observed that this area is not vast enough to be described as luxurious (Murray, 2009: 27), but my analysis argues that it is precisely the dimension and the articulation of the space that are functional to the identity of the hotel. In fact, as it will be discussed, the identity of the hotel is based on elements and characteristics, like cosyness, unpretentiousness, joie de vivre and a certain family feel that are coherent with Missoni S.p.A. identity, which is intrinsically intertwined to the public persona of the Missonis, as noticed before. Moreover, it will be observed how, as a consequence of the above phenomenon, the distinction between hospitality and hospitableness is blurred. The entrance to the lobby presents a marked verticality and is characterised by two gigantic

443

Internation a l

J o u r n a l

o f

M a n a g e m e n t

C a s e s

mosaic vases, results of a collaboration between Missoni S.p.A. and Italian mosaic firm Trend, that almost reach the level of the flooring of the mezzanine where Cucina Restaurant is located. Their proportions are grand and, in comparison, people and furniture seem to be rather small. However, the lobby itself is not characterised by a strong verticality, as that is counterbalanced by the presence of horizontal elements, like the mezzanine and the lower ceilings, that make the lobby appear smaller but also more cosy and intimate than expected. It is the horizontality in fact that characterises the interior of the lobby in contrast with the marked verticality of the outer building, and that concurs in the creation of a coherent identity between different elements and services that complement and enhance each other. Earlier it was mentioned that the lobby consists of an open space where the reception, the bar and the restaurant are located and therefore if we consider the dichotomy continuous/discontinuous we observe that this area belongs to the former term of this opposition. There are in fact no limits to separate the different areas, but simply thresholds, soft boundaries that enhance the conjunction of elements and not their disjunction (see Zilberberg, 2001). The presence of such soft boundaries between the different zones of the lobby enhance its continuity, which in turn emphasises the internal coherence of the space, constituted by the constant references to the world of Missoni, therefore reinforcing the brands essence. However the space comprises different areas that remain distinct at least in function, therefore showing a partitive totality (Giannitrapani, 2004: 3) where the emphasis is not on the wholeness but on the singular parts of the unit. The internal topology of the space, reception on the left, bar in the centre and restaurant upstairs, in fact shows that the lobby area is one open space that represents the sum of different elements, rather than representing an integral totality where the parts lose their individuality. All these different spaces, despite being connected to each other through thresholds and lacking any elements that completely divide the different zones, are dedicated to different functions and retain a certain degree of privacy and intimacy, as shown by a semiotic analysis of visibility. In fact, considering the issues of visibility and of the points of view (Marrone 2001: 291), the lobby presents

areas that remain hidden to the eyes of a localised subject, de facto precluding the complete view of the space. This is particularly evident in the case of the restaurant, located in a mezzanine floor above the bar, that is not even completely visible from the entrance to the lobby downstairs nor from the outside through the glass walls, because a parapet protects it from the bystanders glances. However, the access to it remains perfectly visible through the glass wall that encloses the suspended stairs, therefore signalling the presence of a public space upstairs. The effect is one of turning private spaces into public ones, so that they can represent characteristics that are commonly associated with the former, like privacy, homeliness and cosyness, despite theoretically belonging to the realm of the latter. The mentioned characteristics work well in relation to the Missoni S.p.A. brand, as the fashion label is renowned not only for its peculiar patterns and the abundant use of knitwear, but also for the comfort, wearability, and informality of their garments, that imply a relaxed lifestyle that also reflects the public persona that the Missonis have created through the years, so intrinsically linked to joie de vivre, unpretentiousness and familiarity (see Casadio, 1997). But the name Missoni is also intrinsically linked to the wider phenomenon of made in Italy so that the name is also a synonym for Italian fashion and the quality of its manufacturing. Earlier it was observed how the fashion house Missoni strongly concurred in creating Italian fashions reputation for knitwear, but at the same time the label also relies on the reputation of Italian fashion in general and, in a broader sense, on Italy and its lifestyle. Italian fashion is renowned for its design, the quality of its materials and its excellent craftmanship (see White, 2000) but also for a certain casual elegance, greatly influenced by sportswear (Steele, 2003: 23). These elements concur in creating the prestige and appeal of Italian fashion, that at the same time enhance the reputation of all its exponents, in this case Missoni, that in turn is reflected in the Missoni Hotel brand. Similarly, Italys association with a relaxed lifestyle, characterised by a slow temporality and strictly intertwined with food, conviviality and a pleasurable existence (on the phenomenon of slow living see Parkins 2004 and Parkins and Craig 2004), but also with luxury and style contributes to enhance the appeal of Italian companies and often constitutes strong features

444

I n t e r n a t i o n a l

J o u r n a l

o f

M a n a g e m e n t

C a s es

of their identity (De Vita: 2005). In the same way, Missoni Hotel Edinburghs identity also relies on and refers to the quality of Italian design as well as its lifestyle, emphasising for example the culture of coffee, good food, conviviality and a certain family feel. This is particular evident for example in the Cucina restaurant, a collaboration with renowned chef Giorgio Locatelli. Particularly significant is, firstly, the choice of the restaurants name. Cucina is in fact Italian for kitchen, therefore evoking the simplicity and the domestic preparation of meals, a central element of Italianicity widely recognised and mentioned in the seminal work of Roland Barthes (1977). Secondly, these characteristics of Italianicity are also featured and enhanced in the specific type of cuisine that the Cucina restaurant, under the aegis of head chef Mattia Camorani, proposes. In fact the restaurant proposes dishes inspired by classic Italian cuisine that, despite remaining undoubtedly fine dining, are closely intertwined to domestic tradition, for example in the use of homemade fresh pasta. Another very significant element that concurs in creating the peculiar version of Italianicity featured in the Cucina restaurant, and that reflects itself in the identity of the Edinburghs hotel, is the references to the relaxed Italian lifestyle and its conviviality. In fact customers have the opportunity to sample a sharing menu, where there are no individual orders and everyone gets a taste of everything. This way of eating represents the epitome of the conviviality, joie de vivre and family feel that is strictly associated firstly with the specific Italian lifestyle and secondly with the Missonis public persona, concurring in turn in the creation of Hotel Missonis identity. In this sense, the Cucina restaurant enhances and valorises the family feel so intrinsically related to the Missonis identity with references to the cultural heritage of their country of origin, Italy, both in relation with gastronomy and with lifestyle. Moreover, the family feel is reinforced and echoed in the spatiality of the restaurant, that despite belonging to the bigger unit constitued by the lobby area, is a relatively enclosed and private space that connotes cosyness and warmth.

the Italian fashion industry, particularly in relation with the mother company Missoni S.p.A. The identity of the hotel relies on the brands particular identity and on the characteristics of its founders public persona, but also transcends them featuring services and references that exceed them, creating a space that is inherently coherent. In particular, it was noticed how both the dcor, the spatial dimension and the services enhanced an atmosphere of cosyness, informality and familiarity that strongly evokes not only the fashion label Missoni S.p.A but also the Missonis as ideal host figures. In fact it was observed that despite the limited presence of direct referrals to the Missonis through photographic material, their presence is significantly evoked through their activity as fashion makers specialised in knitwear and through services that are coherent with their philosophy and lifestyle. All these elements contribute to the creation of a very strong host figure in the form of the Missonis, concurring in establishing almost a personal relationship between them and the hotels customer. In this respect, as anticipated above, Missoni Hotel Edinburgh appears to blur the distinction between hospitability and hospitableness as theorised by Brotherton (1999) because both elements are present. In the semiotic analysis of the spaces it was in fact observed how the hotel features connotations of cosyness, homeliness and refers to ideal host figures in the form of the Missonis, displayed in different ways as discussed earlier. However, despite the homely connotations the hotel remains an other place intrinsically different from any domesticity that customers might have experienced, as it refers to a concept of homeliness and hospitableness that is intrinsically linked to the Missonis identity and that relies heavily on Italy and its cultural heritage. This study of the Hotel Missoni Edinburgh demonstrates how both the Italian lifestyle and the prestige of Italian fashion industry constitute important elements of cultural heritage that can be productively employed in the fields of leisure and hospitality marketing. More broadly, however, the present study also contributes to the understanding of a specific niche in those fields, constitute by the expanding phenomenon of international luxury fashion labels entering into the hospitality and leisure business, by adopting a semiotic approach that can complement and support other theoretical conceptualisations in this domain.

Conclusions

The semiotic analysis of the spaces and services of the Missoni Hotel Edinburg identified a series of elements that refer both to the Italian lifestyle and

445

Internation a l

J o u r n a l

o f

M a n a g e m e n t

C a s e s

Bibliography

Arning, C. (2009) Kitsch, irony, and consumerism: A semiotic analysis of Diesel advertising 2000 2008. Semiotica 1741/4: 2148. Barthes, R. (1977) Image-Music-Text. London: Fontana. Bianchi, C. (2005) Spot. Analisi semiotica dellaudiovisivo pubblicitario. Roma: Carocci. Brotherton, B. (1999) Towards a definitive view of the nature of hospitality and hospitality management, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 11, no. 4: 165-173. Casadio, M. (1997) Missoni. London : Thames & Hudson. Ceriani, G. (2001) Marketing moving: lapproccio semiotico. Milano: Franco Angeli. Chevalier, M. and Mazzalovo, G. (2008) Luxury brand management: a world of privilege. Hoboken, NJ ; Chichester : John Wiley. De Vita, E. (2005). Brand Italia. Management Today: 30-35. Donatone, M. (2007) La Red Passion Campari: unanalisi sociosemiotica dello spot The Secret. [Online] E|C Rivista dell Associazione Italiana Studi Semiotici on-line.Available from <http:// www.ec-aiss.it/archivio/tipologico/autore.php> [Accessed 15 February 2011]. Giannitrapani, A. (2004) La cultura del caffe. Uno sguardo sociosemiotico alla Bottega del Caffe. [Online] E|C Rivista dell Associazione Italiana Studi Semiotici on-line. Available from <http:// www.ec-aiss.it/archivio/tematico/alimentazione_ cucina/alimentazione_pratiche.php>. [Accessed 15 February 2011] Floch, J.M. (1988) The contribution of structural semiotics to the design of the hypermarket. International Journal of Research in Marketing 4: 233-252. Floch, J.M. (1990) Smiotique, marketing and communication. Paris: Puf. Floch, Jean-Marie (1995) Identits visuelles. Paris: Puf.

Greimas, A. J. (1966) Smantique structurale. Paris: Larousse. Greimas, A. J. and Courts, J. (1979) Le parcours du savoir, Introduction lanalyse du discours en sciences sociales, Paris, Hachette. Imperi, V. (2010) Il caso Magnum e la costruzione emozionale della brand identity di Algida Un viaggio semiotico tra gli spot Magnum 5 Sensi e Magnum Classic IM. [Online] Ocula Occhio semiotico sui media | Semiotic eye on media. Available from <http://www.ocula.it/files/IMPERIOCULA-Flux-12_%5B2,488.940Mb%5D.pdf> [Accessed 15 February 2011]. Lombardi, M. (2001) Il dolce tuono. Marca e pubblicita nel terzo millennio. Milano: Franco Angeli. Marrone, G. (2001) Corpi sociali. Processi comunicativi e semiotica del testo. Torino: Einaudi. Marrone, G. (2007) Il discorso di marca. Modelli semiotici per il branding. Bari: Laterza. Mick, D. G. et al (2004) Pursuing the Meaning of Meaning in the Commercial World: An International Review of Marketing and Consumer Research Founded on Semiotics. Semiotica 152-1/4: 1-74. Okonkwo, U. (2007). Luxury fashion branding: trends, tactics, techniques. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. Magli, P. (2004) Semiotica. Teoria, metodo, analisi. Venezia: Marsilio. Marsciani, F. and Zinna, A. (1991) Elementi di semiotica generativa. Bologna: Esculapio. Moore, C. M. (2000) Streets of style: fashion designer retailing within London and New York. Commercial cultures: economies, practices, spaces. edited by Peter Jackson et al. Oxford : Berg. Naughton, J. (2005) Lauder, Missoni Unveil Beauty Brand. WWD: Womens Wear Daily, November 11. Steele, V. (2003) Fashion, Italian style. New Haven, Conn.; London: Yale University.

446

I n t e r n a t i o n a l

J o u r n a l

o f

M a n a g e m e n t

C a s es

Murray, A. (2009) The multi-faceted hotel Missoni. Architects Journal: 22-29. Parkins, W. (2004) At home in Tuscany: slow living and the cosmopolitan subject. Home Cultures 1(3): 253-274. Parkins, W. and Craig, G. (2004) Slow living. Oxford: Berg. Rezidor Hotel Group (2010) Fact sheet 2010. [Online] Available at: <http://phx.corporate-ir.net/ External.File?item=UGFyZW50SUQ9ODY1MXxD aGlsZElEPS0xfFR5cGU9Mw==&t=1> [Accessed 22 February 2011]. Semprini, A. (1993) Marche e mondi possibili. Milano: Franco Angeli. Semprini, A. (1996) La marca. Milano: Lupetti. Semprini, A. (1997) Analizzare la comunicazione. Milano: Franco Angeli. Semprini, A. (2003) Lo sguardo sociosemiotico. Comunicazione, marche, media, pubblicita. Milano: Franco Angeli Semprini, A. (2006) La marca postmoderna. Milano: Franco Angeli. White, N. (2000) Reconstructing Italian fashion : America and the development of the Italian fashion industry. Oxford : Berg. Zilberberg, C. (2001) Soglie, limiti, valori. Semiotica in Nuce Volume II. Teoria del discorso. Roma: Meltemi.

447

Copyright of International Journal of Management Cases is the property of Access Press UK and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- The Artification of Luxury Fashion Brands: Synergies, Contaminations, and HybridizationsFrom EverandThe Artification of Luxury Fashion Brands: Synergies, Contaminations, and HybridizationsMarta MassiNo ratings yet

- Perpetual Prestige How Marketing Strategies Have Made Luxury Brands TimelessFrom EverandPerpetual Prestige How Marketing Strategies Have Made Luxury Brands TimelessNo ratings yet

- Idm MoschinoDocument9 pagesIdm MoschinoDileshaa ParakhNo ratings yet

- Idm MoschinoDocument9 pagesIdm MoschinoDileshaa ParakhNo ratings yet

- Metis PR & Communications: Bespoke PR, Branding & Storytelling StrategiesDocument23 pagesMetis PR & Communications: Bespoke PR, Branding & Storytelling StrategiescarlNo ratings yet

- Luxury Lifestyle Business Beyond BuzzwordsDocument14 pagesLuxury Lifestyle Business Beyond BuzzwordsShane Sanders100% (1)

- Spain Culture BrandDocument218 pagesSpain Culture BrandkaparadkarNo ratings yet

- Reseña de Monografia #3Document2 pagesReseña de Monografia #3vc79592111No ratings yet

- CP Eng LowDocument27 pagesCP Eng LowAleister FerguciNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement On Italian CultureDocument5 pagesThesis Statement On Italian CultureHelpWithFilingDivorcePapersSalem100% (2)

- Albergo Diffuso English VersionDocument19 pagesAlbergo Diffuso English VersionromanadusperNo ratings yet

- Brand ManagementDocument6 pagesBrand ManagementVIDHINo ratings yet

- European Luxury Fashion Brand Advertising and MarketingDocument18 pagesEuropean Luxury Fashion Brand Advertising and Marketingl1419584124No ratings yet

- Question 1Document31 pagesQuestion 1Claudia NgoNo ratings yet

- Senior Capstone PaperDocument14 pagesSenior Capstone PaperDemi LeBlancNo ratings yet

- United Colors of Benetton Advert Proposal: Brand Development and Communication StrategiesDocument62 pagesUnited Colors of Benetton Advert Proposal: Brand Development and Communication StrategiesApoorv SharmaNo ratings yet

- Ucb ReportDocument50 pagesUcb ReportlizaNo ratings yet

- 504Document29 pages504Rud BoruahNo ratings yet

- Braeden Mcleod Culture-Midterm ItalyDocument10 pagesBraeden Mcleod Culture-Midterm Italyapi-645946598No ratings yet

- S Pelaggi-SociologyofMadeinItaly ASocialHistoryDocument14 pagesS Pelaggi-SociologyofMadeinItaly ASocialHistoryMarta SatoriNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Lodging Operations Module 1Document2 pagesFundamentals of Lodging Operations Module 1cheNo ratings yet

- Case Study Louis Vuitton in ChinaDocument6 pagesCase Study Louis Vuitton in ChinaalejandraNo ratings yet

- Historical Book: La Rinascente. Franco Albini and Franca Helg.Document21 pagesHistorical Book: La Rinascente. Franco Albini and Franca Helg.Maria Camila Rodriguez100% (1)

- Brand Equity Is The Sum Total of All The Different Values That People Attach To A Brand, and Is NotDocument8 pagesBrand Equity Is The Sum Total of All The Different Values That People Attach To A Brand, and Is NotJayesh AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Louis Vuitton Brand Extension Case StudyDocument47 pagesLouis Vuitton Brand Extension Case Studyridhi0412100% (2)

- Bottega VenetaDocument67 pagesBottega VenetaSaurabh ChandraNo ratings yet

- 2016 Company Profile EngDocument2 pages2016 Company Profile Engestagio ione fiuzaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - Hospitality IndustryDocument49 pagesChapter 1 - Hospitality Industrygraziel doronilaNo ratings yet

- DR Jessica Bugg The Shifting Focus: Culture, Fashion & IdentityDocument8 pagesDR Jessica Bugg The Shifting Focus: Culture, Fashion & Identitycarlos santanaNo ratings yet

- ENTREPRENEURSHIP Crossroads of EntrepreneurshipDocument298 pagesENTREPRENEURSHIP Crossroads of Entrepreneurshipbonar na70No ratings yet

- Baselwrapbrand 1Document23 pagesBaselwrapbrand 1muthum44499335No ratings yet

- Benetton PDFDocument32 pagesBenetton PDFdivashreebNo ratings yet

- H&MDocument14 pagesH&MNeha SinghNo ratings yet

- Bespoke and Made-to-Measure Tailoring For Men: Study of A Valuable Branch of The Menswear MarketDocument74 pagesBespoke and Made-to-Measure Tailoring For Men: Study of A Valuable Branch of The Menswear MarketArthur O'Twenty100% (2)

- Brand StormingDocument234 pagesBrand StormingebussfNo ratings yet

- 108 6621495 PDFDocument1 page108 6621495 PDFCieloNo ratings yet

- Overview of The Hospitality IndustryDocument20 pagesOverview of The Hospitality IndustryManguerra, Kim Jezhreel N.No ratings yet

- Бляхар Віолетта БКП-21Document11 pagesБляхар Віолетта БКП-21violiettaNo ratings yet

- Jeel (2017-2020) Final BookDocument79 pagesJeel (2017-2020) Final BookShaikaNo ratings yet

- Benetton CaseDocument17 pagesBenetton CaseSrinivas Reddy PalugullaNo ratings yet

- MOSCHINO Case Study Part 1Document16 pagesMOSCHINO Case Study Part 1Akanksha SobtiNo ratings yet

- 2002 - Chevalier - The Cultural Construction of Domestic Space in France and Great BritainDocument11 pages2002 - Chevalier - The Cultural Construction of Domestic Space in France and Great BritainMadalena van ZellerNo ratings yet

- Company Profile Company ProfileDocument26 pagesCompany Profile Company ProfileDimasRianNo ratings yet

- Luxury Brand Management Hugo BossDocument75 pagesLuxury Brand Management Hugo BossEscuela Goymar Galicia80% (5)

- The KitchenDocument4 pagesThe KitchenLesley Liavoga SandeNo ratings yet

- Boutique Hotel 2Document17 pagesBoutique Hotel 2Ocirej OrtsacNo ratings yet

- 8223-Article Text-26539-1-10-20180724 PDFDocument19 pages8223-Article Text-26539-1-10-20180724 PDFPratik MeswaniyaNo ratings yet

- De VILLA - A1-GED105 - Local Becoming GlobalDocument3 pagesDe VILLA - A1-GED105 - Local Becoming Globalbeary whiteNo ratings yet

- Genius Loci Italy EngDocument37 pagesGenius Loci Italy EngMarlenne Perez MaillardNo ratings yet

- Lecture 7Document25 pagesLecture 7IbrahimshoaibNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1 - Applied EthicsDocument7 pagesLecture 1 - Applied EthicsDonn Jeremi CastilloNo ratings yet

- Dolce and GabbanaDocument40 pagesDolce and GabbanaDimple Parmar0% (1)

- Jeffry Edano Midterm-MACRODocument10 pagesJeffry Edano Midterm-MACROJeffry EdanoNo ratings yet

- Cross-Cultural Management ProjectDocument8 pagesCross-Cultural Management ProjectLori CristeaNo ratings yet

- Belgeo 43367Document27 pagesBelgeo 43367LolazzoNo ratings yet

- Cultural Sensitivity Needed for Foreign Business RelationsDocument6 pagesCultural Sensitivity Needed for Foreign Business RelationsEri.tina.yara GarroNo ratings yet

- Luxury From Luxus To MasstigeDocument24 pagesLuxury From Luxus To MasstigeMuneeb VohraNo ratings yet

- Grade XII - Notes - UNIT 3Document19 pagesGrade XII - Notes - UNIT 3garimasrivastava2021No ratings yet

- Waiters' Training ManualDocument25 pagesWaiters' Training ManualKoustav Ghosh90% (51)

- L'EBITDA Consapevole. Luci, forme e colori dell'architettura alberghieraFrom EverandL'EBITDA Consapevole. Luci, forme e colori dell'architettura alberghieraNo ratings yet

- Oecd Principle For Integrity in Public ProcurementDocument142 pagesOecd Principle For Integrity in Public ProcurementNatika_IndieLVNo ratings yet

- MM Chapter 11Document47 pagesMM Chapter 11Raven BlackNo ratings yet

- Loyalty and Satisfaction Construct in Retail Banking-An Empirical Study On Bank CustomersDocument16 pagesLoyalty and Satisfaction Construct in Retail Banking-An Empirical Study On Bank CustomersrajasekaransvnNo ratings yet

- Online Travel Service Quality: The Role of Pre-Transaction ServicesDocument20 pagesOnline Travel Service Quality: The Role of Pre-Transaction ServicesRaven BlackNo ratings yet

- Do Animated WebsiteDocument27 pagesDo Animated WebsiteRaven BlackNo ratings yet

- BUSINESS RESEARCH METHODSDocument10 pagesBUSINESS RESEARCH METHODSKireinaArchangelNo ratings yet

- MM Chapter 3Document21 pagesMM Chapter 3Raven BlackNo ratings yet

- Two Essays On The Post-earnings-Announcement DriftDocument148 pagesTwo Essays On The Post-earnings-Announcement DriftRaven BlackNo ratings yet

- Do Animated WebsiteDocument27 pagesDo Animated WebsiteRaven BlackNo ratings yet

- Mass Media Effects TheoriesDocument12 pagesMass Media Effects TheoriesTedi0% (1)

- Facebook Twitter Reddit Linkedin Whatsapp: Overall IntroductionDocument12 pagesFacebook Twitter Reddit Linkedin Whatsapp: Overall Introductionapoc lordNo ratings yet

- Maria Khalid DC200200169 PSY632 Assignment No. 2Document2 pagesMaria Khalid DC200200169 PSY632 Assignment No. 2Maria KhalidNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Study On Consumer Behaviour About Colgate and Pepsodent PasteDocument32 pagesA Comparative Study On Consumer Behaviour About Colgate and Pepsodent Pastesarvajith100% (1)

- Pest AnalysisDocument2 pagesPest AnalysisRupesh LimbaniNo ratings yet

- Life Style Profiles of Social Class: Presented ByDocument18 pagesLife Style Profiles of Social Class: Presented BybkaaljdaelvNo ratings yet

- MAPEH (P.E.) : Quarter 1 - Module 1: Active Recreation (Lifestyle)Document10 pagesMAPEH (P.E.) : Quarter 1 - Module 1: Active Recreation (Lifestyle)Albert Ian CasugaNo ratings yet

- Transitional SpacesDocument4 pagesTransitional SpacesSunaina ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Consumer Behaviour Project ReportDocument40 pagesConsumer Behaviour Project ReportMeenu Mohan100% (1)

- Curriculum Map Mapeh: Lifestyle and Weight ManagementDocument7 pagesCurriculum Map Mapeh: Lifestyle and Weight ManagementJulie Ann Talento100% (1)

- Color and Pattern Analysis in Romanian Folk ClothingDocument14 pagesColor and Pattern Analysis in Romanian Folk ClothingshandryssNo ratings yet

- Consumer lifestyle segments in Europe based on needs and valuesDocument1 pageConsumer lifestyle segments in Europe based on needs and valuesBingo BountiesNo ratings yet

- Consumer Behavior Towards AppleDocument86 pagesConsumer Behavior Towards AppleLusiana Rani OktavianiNo ratings yet

- Cultural Values in Advertisements To The Chinese X Generation PDFDocument11 pagesCultural Values in Advertisements To The Chinese X Generation PDFIleanaNo ratings yet

- Into The WildDocument12 pagesInto The Wildalojz9897No ratings yet

- Lang2019 - Plant Based MeatDocument9 pagesLang2019 - Plant Based MeatRenaldy NugrahaNo ratings yet

- Consumption Culture Identity Syllabus 2018Document8 pagesConsumption Culture Identity Syllabus 2018CaitlinNo ratings yet

- Journal of Economic Education: Herawati, Sucihatiningsih Dian Wisika Prajanti, KardoyoDocument11 pagesJournal of Economic Education: Herawati, Sucihatiningsih Dian Wisika Prajanti, KardoyoYeni RachmanNo ratings yet

- By Korbinian Johannes WeiratherDocument5 pagesBy Korbinian Johannes WeiratherJohannes WeiratherNo ratings yet

- Emotional Marketing, RytelDocument10 pagesEmotional Marketing, RytelHillary Pimentel LimaNo ratings yet

- The Mediating Effect of Sustainable Consumption atDocument16 pagesThe Mediating Effect of Sustainable Consumption atIxora MyNo ratings yet

- Market Segmentation in MalaysiaDocument8 pagesMarket Segmentation in MalaysiaAli AhsamNo ratings yet

- Wife Swap - The Norwegian VersionDocument6 pagesWife Swap - The Norwegian VersionGunn EnliNo ratings yet

- PakulskiDocument26 pagesPakulskiCamila AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Habits Routines Sustainable Lifestyles EVO502 Final Summary Report Nov 20112Document71 pagesHabits Routines Sustainable Lifestyles EVO502 Final Summary Report Nov 20112claupyNo ratings yet

- Fashion Forcasting 1Document45 pagesFashion Forcasting 1Spring starNo ratings yet

- Who Indigenous Peoples AreDocument17 pagesWho Indigenous Peoples AreNicaela MaderazoNo ratings yet

- CLPNA 2014 Think Tank Eloy Van HalDocument59 pagesCLPNA 2014 Think Tank Eloy Van Haljuan david cormaneNo ratings yet

- Carpentry 7 Curriculum GuideDocument5 pagesCarpentry 7 Curriculum GuideArnel BoholstNo ratings yet

- Citta Slow, Slow Cities Slow FoodDocument13 pagesCitta Slow, Slow Cities Slow Foodcupcake121No ratings yet