Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Review of Cheng Astounding Wonder Imagining Science and Science Fiction in Interwar America

Uploaded by

Boris VelinesCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Review of Cheng Astounding Wonder Imagining Science and Science Fiction in Interwar America

Uploaded by

Boris VelinesCopyright:

Available Formats

Astounding Wonder: Imagining Science and Science Fiction in Interwar America by John Cheng (review)

J. P. Telotte

Technology and Culture, Volume 54, Number 2, April 2013, pp. 417-419 (Article) Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: 10.1353/tech.2013.0073

For additional information about this article

http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/tech/summary/v054/54.2.telotte.html

Access provided by University of Arizona (7 Sep 2013 14:31 GMT)

B O O K

R E V I E W S

what did they produce? And what was their influence? And throughout my reading, I also could not keep from wondering what marvels might have come from this study if McLaren had invited some of the feminist science and technology scholars into his discussions. His wonderfully told history would probably have benefited from these scholars frequent dealings with the relations and inter- and intra-actions between humans and technology.

MARIA BJRKMAN

Maria Bjrkman is a historian of science and medicine at Uppsala University, Sweden. Her Ph.D. deals with the history of Swedish eugenics.

Astounding Wonder: Imagining Science and Science Fiction in Interwar America. By John Cheng. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012. Pp. vi+392. $45.

I was initially led to expect something different from John Chengs Astounding Wonder, for the introduction suggested that the book would offer a chronicle of attitudes toward science and technology in the interwar era, that is, from the 1920s to approximately 1941. This subject has been taken up many times in recent years, notably by commentators such as Cecelia Tichi, Miles Orvell, and Gary Westfahlunfortunately, none of their work is cited hereand always to interesting ends. For this subject, what Cheng describes as the significance and evolving circumstances for what might be called popular science in the early Twentieth Century (p. 3) has become a crucial touchstone for explaining how interwar attitudes along with World War IIhelped shape our modern technological world. But Chengs effort surprised by moving such discussions in a new direction, one that is well worth the effort. As the first chapter clarifies, his real interest lies in linking the development of interwar popular science to that of science fiction, particularly as it took shape in the world of the pulp magazines, such as Amazing Stories, Astounding Stories, and Wonder Stories (originally Science Wonder Stories ), from whose names Cheng draws his own title. Chengs focus ultimately is on the ways in which scientific thinking and the imaginationparticularly what might be termed the literary imaginationwere intertwined in this formative period. As he suggests, imagining science and imagining it passionately were part and parcel of both cultures (p. 6), that of science and its trained practitioners on the one hand and that of the writers and readers of the new literature of science fiction on the other. Drawing on the examples of early rocket experimenter Robert Goddard and the members of the ambitiously named American Interplanetary Society, he notes that science in early-twentieth-century America was

417

T E C H N O L O G Y

A N D

C U LT U R E

APRIL 2013 VOL. 54

never really an individual activity; rather, it was presented in newspapers and the pulp magazines as a kind of inclusive enterprise (p. 255). Thus, each new breakthrough seemed to catch the publics attention, to open up popular discussion and debate, and even to bring out volunteers eager to participate, as in the case of those who, responding to news stories about rockets possibly being able to reach the moon, volunteered to take the potentially one-way trip. His larger point is that science was part of a social and progressive sensibility (p. 4), a sensibility that was mirrored in and furthered by both the writing and the reading of science fiction in this era. While a number of histories of science fiction have made similar connections, Chengs documentation of the extent to which readers of science fiction tended to see themselves as potential scientists or even scientists in factrepresents a valuable contribution to our understanding of the place of the pulp magazines in interwar popular culture and in the cultural history of science. For while others have mined the pulp archives to determine what types of stories were written, published, and appreciated in this period, which prominent authors first found their way through the venues of Amazing, Astounding, Wonder, and their less successful brethren, and how much these journals editors helped set the trajectory for a developing science fiction literature, much less attention has been paid to the readership itself. Here Cheng, in great detail, mines the letters to the editors of the journals, the open letters forums, and even individual correspondence, demonstrating how these various communications led to exchanges within and through the backyard of their pulps, and for many, to activities beyond them (p. 215), such as the formation of science clubs, collaboration on rocket projects, the creation of a separate fan fiction and fan-published journals, and eventually to the first fan conventions, or Cons, as they are familiarly known today. It is this fan engagement that gradually becomes the real focus of Astounding Wonderas well as its real strength, allowing it to become an important piece of cultural anthropology, as it gives a very human face to emerging scientific culture. Despite that accomplishment, Astounding Wonder does have its flaws and irritations. As suggested above, Cheng privileges his primary materialsi.e., the letters and columns that he so effectively mineswhile overlooking many key histories of science fiction, many of which have similarly sought to fix their subject in a broad cultural context. While there are a few references to science fiction comic strips, there is no real discussion of the films they inspiredthe Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers serials, for exampleor of a similarly developing science fiction cinema of this period. And the book is simply in need of a good editing to remove the many repetitions and long-winded discussions; while a satisfying read, it could be much better. However, these should not be taken as strong objections to the book. It is a significant work that can be recommended for anyone interested in that

418

B O O K

R E V I E W S

crucial dual development of the early twentieth century: a scientific and technological consciousness and the science fiction imagination.

J. P. TELOTTE

J. P. Telotte is professor of Film and Media Studies and former chair of the School of Literature, Media, and Communication at Georgia Tech. Coeditor of the journal Post Script, he has published numerous books on science fiction film and television, among them Replications: A Robotic History of the Science Fiction Film (1995), A Distant Technology: Science Fiction Film and the Machine Age (1999), Science Fiction Film (2001), and The Essential Science Fiction Television Reader (2008).

Into the Cosmos: Space Exploration and Soviet Culture. Edited by James T. Andrews and Asif A. Siddiqi. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2011. $27.95.

Before Neil Armstrongs historic moonwalk in July of 1969, the Soviet Union dominated the exploration of space, to the chagrin of Americans and the delight of Soviet citizens. Between 1957 and 1963, the Soviets launched the first satellite into orbit and the first satellite with a live passenger (a dog named Laika). It boasted the first human spaceflight and sent the first woman into space. Into the Cosmos is a cultural history of the first generation of Soviet space exploration that reveals that space program to have been a crucial cultural touchstone for Soviet citizens throughout the 1950s and 1960s. This edited volume provides examples of how the first generation of Soviet space exploration affected cosmonauts, ordinary citizens, and everyday life in the former Soviet Union. Because the Soviet space program was run by the military, much of it was secretive and details about spacecraft, plans for future launches, rocket designers, and even the location of the launch site in rural Kazakhstan were classified information. Rockets that could propel humans into outer space could also carry bombs across oceans and continents, and while this early chapter of the U.S.-Soviet space race was couched in terms of friendly competition, it had potentially bellicose ulterior motives. Many documents about the space program remain classified and the contributors to this volume have relied primarily on published sources including memoirs, Russian-language newspapers, scientific volumes, and other journals. Only James Andrewss chapter on Konstantin Tsiolkovskii, a rocket scientist and space enthusiast from the early twentieth century, contains a significant number of original archival materials. The first section of the book gives an overview of the topic. Alexei Kojevnikov describes the Soviet space program in the broader cultural context of the 1950s and 1960s and James Andrews traces the longer history of Russian and early Soviet fascination with space travel. The second section

419

You might also like

- (READING LIST) Gender, Race, Sexuality and SurveillanceDocument7 pages(READING LIST) Gender, Race, Sexuality and SurveillanceBoris VelinesNo ratings yet

- Bourdieu 1975 Specificity of The Scientific FieldDocument6 pagesBourdieu 1975 Specificity of The Scientific FieldBoris VelinesNo ratings yet

- Knowledge Power Nature Syllabus Spring 2016Document12 pagesKnowledge Power Nature Syllabus Spring 2016Boris VelinesNo ratings yet

- Teachers Guide For in The Light of ReverenceDocument48 pagesTeachers Guide For in The Light of ReverenceBoris VelinesNo ratings yet

- Interview With Latour Whole World Is Becoming STSDocument19 pagesInterview With Latour Whole World Is Becoming STSBoris VelinesNo ratings yet

- Guide - Action - Discussion - in The Light of ReverenceDocument8 pagesGuide - Action - Discussion - in The Light of ReverenceBoris VelinesNo ratings yet

- Interview With Latour Whole World Is Becoming STSDocument19 pagesInterview With Latour Whole World Is Becoming STSBoris VelinesNo ratings yet

- Rabinow American ModernsDocument14 pagesRabinow American ModernsBoris VelinesNo ratings yet

- Anders 1958 The Obsolescence of Privacy PDFDocument27 pagesAnders 1958 The Obsolescence of Privacy PDFBoris VelinesNo ratings yet

- Kaiser Permanente - ImmunizationsDocument1 pageKaiser Permanente - ImmunizationsBoris VelinesNo ratings yet

- Swanner Gsas - Harvard 0084L 10781Document567 pagesSwanner Gsas - Harvard 0084L 10781Boris VelinesNo ratings yet

- Syllabus Braitberg Privacy Colloquium Fall 2016 RevisedDocument7 pagesSyllabus Braitberg Privacy Colloquium Fall 2016 RevisedBoris VelinesNo ratings yet

- Cultures of Surveillance Course Description For Spring 2016Document1 pageCultures of Surveillance Course Description For Spring 2016Boris VelinesNo ratings yet

- GAO Report On Fish and Wildlife Biological OpinionDocument11 pagesGAO Report On Fish and Wildlife Biological OpinionBoris VelinesNo ratings yet

- Electronic Presence Diary AnalysisDocument3 pagesElectronic Presence Diary AnalysisBoris VelinesNo ratings yet

- Checklist For Final PaperDocument1 pageChecklist For Final PaperBoris VelinesNo ratings yet

- Homophilia Extra CreditDocument2 pagesHomophilia Extra CreditBoris VelinesNo ratings yet

- Instructions For Background ReasearchDocument3 pagesInstructions For Background ReasearchBoris VelinesNo ratings yet

- Instuctions and Rubric For Final AssignmentDocument2 pagesInstuctions and Rubric For Final AssignmentBoris VelinesNo ratings yet

- Criteria Level 4 Level 3 Level 2 Level 1 Level 0Document2 pagesCriteria Level 4 Level 3 Level 2 Level 1 Level 0Boris VelinesNo ratings yet

- Braitberg Bodies and Machines MWF Fall 2015 Syllabus FinalDocument8 pagesBraitberg Bodies and Machines MWF Fall 2015 Syllabus FinalBoris VelinesNo ratings yet

- Instructions For Final PaperDocument4 pagesInstructions For Final PaperBoris VelinesNo ratings yet

- Crisis at The Border Policy BriefDocument5 pagesCrisis at The Border Policy BriefBoris VelinesNo ratings yet

- Presentation On Stereotyes Racism and The HolocaustDocument43 pagesPresentation On Stereotyes Racism and The HolocaustBoris VelinesNo ratings yet

- Cornelius 2001 Death at The Border Efficacy and Unintended Cosnmequences of US Immigration Control PolicyDocument25 pagesCornelius 2001 Death at The Border Efficacy and Unintended Cosnmequences of US Immigration Control PolicyBoris VelinesNo ratings yet

- Animism in The Sciences Then and Now - E-FluxDocument11 pagesAnimism in The Sciences Then and Now - E-FluxBoris VelinesNo ratings yet

- Migrant Deaths and Border EnforcementDocument16 pagesMigrant Deaths and Border EnforcementBoris VelinesNo ratings yet

- Border Patrol Strategic Plan 1994 and BeyondDocument19 pagesBorder Patrol Strategic Plan 1994 and BeyondCEInquiryNo ratings yet

- Commercial Surrogacy Commodification or ChoiceDocument3 pagesCommercial Surrogacy Commodification or ChoiceBoris VelinesNo ratings yet

- Syllabus Fall 2015 DraftDocument7 pagesSyllabus Fall 2015 DraftBoris VelinesNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Basic First AidDocument31 pagesBasic First AidMark Anthony MaquilingNo ratings yet

- Digital Communication QuestionsDocument14 pagesDigital Communication QuestionsNilanjan BhattacharjeeNo ratings yet

- RPG-7 Rocket LauncherDocument3 pagesRPG-7 Rocket Launchersaledin1100% (3)

- Emerson EPC48150 1800 FA1EPC48300 3200 FA1 V PDFDocument26 pagesEmerson EPC48150 1800 FA1EPC48300 3200 FA1 V PDFRicardo Andrés Soto Salinas RassNo ratings yet

- Henry Stevens - Hitler's Flying Saucers - A Guide To German Flying Discs of The Second World War New Edition (2013, Adventures Unlimited Press) - Libgen - lc-116-120Document5 pagesHenry Stevens - Hitler's Flying Saucers - A Guide To German Flying Discs of The Second World War New Edition (2013, Adventures Unlimited Press) - Libgen - lc-116-120sejoh34456No ratings yet

- Final Decision W - Cover Letter, 7-14-22Document19 pagesFinal Decision W - Cover Letter, 7-14-22Helen BennettNo ratings yet

- Reflective Essay 4Document1 pageReflective Essay 4Thirdy AngelesNo ratings yet

- Discuss The Challenges For Firms To Operate in The Hard-Boiled Confectionery Market in India?Document4 pagesDiscuss The Challenges For Firms To Operate in The Hard-Boiled Confectionery Market in India?harryNo ratings yet

- VivsayamDocument87 pagesVivsayamvalarumsakthi100% (2)

- JK Paper Q4FY11 Earnings Call TranscriptDocument10 pagesJK Paper Q4FY11 Earnings Call TranscriptkallllllooooNo ratings yet

- Aleister Crowley and the SiriansDocument4 pagesAleister Crowley and the SiriansJCMNo ratings yet

- Indian Patents. 232467 - THE SYNERGISTIC MINERAL MIXTURE FOR INCREASING MILK YIELD IN CATTLEDocument9 pagesIndian Patents. 232467 - THE SYNERGISTIC MINERAL MIXTURE FOR INCREASING MILK YIELD IN CATTLEHemlata LodhaNo ratings yet

- Design of Fixed Column Base JointsDocument23 pagesDesign of Fixed Column Base JointsLanfranco CorniaNo ratings yet

- WOOD Investor Presentation 3Q21Document65 pagesWOOD Investor Presentation 3Q21Koko HadiwanaNo ratings yet

- AI Model Sentiment AnalysisDocument6 pagesAI Model Sentiment AnalysisNeeraja RanjithNo ratings yet

- Problem SolutionsDocument5 pagesProblem SolutionskkappaNo ratings yet

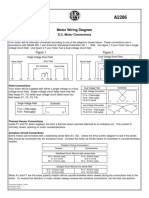

- Motor Wiring Diagram: D.C. Motor ConnectionsDocument1 pageMotor Wiring Diagram: D.C. Motor Connectionsczds6594No ratings yet

- Guidance Notes Blow Out PreventerDocument6 pagesGuidance Notes Blow Out PreventerasadqhseNo ratings yet

- Elevator Traction Machine CatalogDocument24 pagesElevator Traction Machine CatalogRafif100% (1)

- Evolutionary PsychologyDocument10 pagesEvolutionary PsychologyShreya MadheswaranNo ratings yet

- 47-Article Text-338-1-10-20220107Document8 pages47-Article Text-338-1-10-20220107Ime HartatiNo ratings yet

- CAE The Most Comprehensive and Easy-To-Use Ultrasound SimulatorDocument2 pagesCAE The Most Comprehensive and Easy-To-Use Ultrasound Simulatorjfrías_2No ratings yet

- Lesson 2 Socio Anthropological View of The SelfDocument12 pagesLesson 2 Socio Anthropological View of The SelfAilyn RamosNo ratings yet

- DK Children Nature S Deadliest Creatures Visual Encyclopedia PDFDocument210 pagesDK Children Nature S Deadliest Creatures Visual Encyclopedia PDFThu Hà100% (6)

- Tutorial On The ITU GDocument7 pagesTutorial On The ITU GCh RambabuNo ratings yet

- Patent for Fired Heater with Radiant and Convection SectionsDocument11 pagesPatent for Fired Heater with Radiant and Convection Sectionsxyz7890No ratings yet

- Crew Served WeaponsDocument11 pagesCrew Served WeaponsKyle Fagin100% (1)

- Liquid Out, Temperature 25.5 °C Tube: M/gs P / WDocument7 pagesLiquid Out, Temperature 25.5 °C Tube: M/gs P / WGianra RadityaNo ratings yet

- Pharmacokinetics and Drug EffectsDocument11 pagesPharmacokinetics and Drug Effectsmanilyn dacoNo ratings yet

- 07.03.09 Chest Physiotherapy PDFDocument9 pages07.03.09 Chest Physiotherapy PDFRakesh KumarNo ratings yet