Professional Documents

Culture Documents

New Zealand

Uploaded by

alysonmicheaalaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

New Zealand

Uploaded by

alysonmicheaalaCopyright:

Available Formats

New Zealand From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This article is about the country.

For other uses, see New Zealand (disambiguati on). "NZ" redirects here. For other uses, see NZ (disambiguation). Page move-protectedPage semi-protected New Zealand Aotearoa Flag Coat of arms Anthem: God Defend New Zealand God Save the Queen[n 1] Location of New Zealand and the Ross Dependency Location of New Zealand and the Ross Dependency Capital Wellington 4117'S 17427'E Largest city Auckland Official languages 95.9% English[n 2] 4.2% Maori 0.6% NZ Sign Language Ethnic groups 77.0% European / other[n 3][5] 15% Maori 10% Asian 7% Pacific peoples 0.9% Middle Eastern, Latin American, African Demonym New Zealander Kiwi (colloquial) Government Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy Monarch Elizabeth II Governor-General Sir Jerry Mateparae Prime Minister John Key Legislature Parliament (House of Representatives) Independence from the United Kingdom New Zealand Constitution Act 1852 17 January 1853 Dominion 26 September 1907 Statute of Westminster 1931 11 December 1931 Realm of New Zealand created 25 November 1947 Constitution Act 1986 13 December 1986 Area Total 268,021 km2 (75th) 103,483 sq mi Water (%) 1.6[n 4] Population June 2013 estimate 4,468,200[7] (122nd) 2006 census 4,027,947[8] Density 16.5/km2 (202nd) 42.7/sq mi GDP (PPP) 2011 estimate Total $122.193 billion[9] Per capita $27,668[9] GDP (nominal) 2011 estimate Total $161.851 billion[9] Per capita $36,648[9] Gini (1997) 36.2[10]

medium HDI (2013) Increase 0.919[11] very high 6th Currency New Zealand dollar (NZD) Time zone NZST[n 5] (UTC+12) Summer (DST) NZDT (UTC+13) (Sep to Apr) Date format dd/mm/yyyy Drives on the left Calling code +64 ISO 3166 code NZ Internet TLD .nz New Zealand (/nju?'zi?l?nd/; Maori: Aotearoa [a?'t?a??a]) is an island country i n the southwestern Pacific Ocean. The country geographically comprises two main landmasses ? that of the North and South Islands ? and numerous smaller islands. New Zealand is situated some 1,500 kilometres (900 mi) east of Australia across the Tasman Sea and roughly 1,000 kilometres (600 mi) south of the Pacific islan d nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga. Because of its remoteness, it was o ne of the last lands to be settled by humans. During its long isolation, New Zea land developed a distinctive biodiversity of animal, fungal and plant life; most notable are the large number of unique bird species. The country's varied topog raphy and its sharp mountain peaks owe much to the tectonic uplift of land and v olcanic eruptions. Polynesians settled New Zealand in 1250 1300 CE and developed a distinctive Maori culture. The first non-Maori contact with New Zealand happened when Dutch explor er Abel Tasman sighted the island in 1642 CE.[12] The introduction of potatoes a nd muskets triggered upheaval among Maori early during the 19th century, which l ed to the inter-tribal Musket Wars. In 1840 the British and Maori signed a treat y making New Zealand a colony of the British Empire. Immigrant numbers increased sharply and conflicts escalated into the New Zealand Wars, which resulted in mu ch Maori land being confiscated in the mid North Island. Economic depressions we re followed by periods of political reform, with women gaining the vote during t he 1890s, and a welfare state being established from the 1930s. After World War II, New Zealand joined Australia and the United States in the ANZUS security tre aty, although the United States later suspended the treaty. New Zealanders enjoy ed one of the highest standards of living in the world in the 1950s, but the 197 0s saw a deep recession, worsened by oil shocks and the United Kingdom's entry i nto the European Economic Community. The country underwent major economic change s during the 1980s, which transformed it from a protectionist to a liberalised f ree trade economy; once-dominant exports of wool have been overtaken by dairy pr oducts, meat, and wine. The majority of New Zealand's population is of European descent; the indigenous Maori are the largest minority, followed by Asians and non-Maori Polynesians. En glish, Maori and New Zealand Sign Language are the official languages, with Engl ish predominant. Much of New Zealand's culture is derived from Maori and early B ritish settlers. Early European art was dominated by landscapes and to a lesser extent portraits of Maori. A recent resurgence of Maori culture has seen their t raditional arts of carving, weaving and tattooing become more mainstream. The co untry's culture has also been broadened by globalisation and increased immigrati on from the Pacific Islands and Asia. New Zealand's diverse landscape provides m any opportunities for outdoor pursuits and has provided the backdrop for a numbe r of big budget movies. New Zealand is organised into 11 regional councils and 67 territorial authoritie s for local government purposes; these have less autonomy than the country's lon g defunct provinces did. Nationally, executive political power is exercised by t he Cabinet, led by the Prime Minister. Queen Elizabeth II is the country's head of state and is represented by a Governor-General. The Queen's Realm of New Zeal and also includes Tokelau (a dependent territory); the Cook Islands and Niue (se lf-governing but in free association); and the Ross Dependency, which is New Zea land's territorial claim in Antarctica. New Zealand is a member of the Asia-Paci

fic Economic Cooperation, Commonwealth of Nations, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Pacific Islands Forum, and the United Nations. Contents [hide] 1 Etymology 2 History 3 Politics 3.1 Government 3.2 Foreign relations and the military 3.3 Local government and external territories 4 Environment 4.1 Geography 4.2 Climate 4.3 Biodiversity 5 Economy 5.1 Trade 5.2 Infrastructure 6 Demography 6.1 Ethnicity and immigration 6.2 Language 6.3 Education and religion 7 Culture 7.1 Art 7.2 Literature 7.3 Entertainment 7.4 Sports 8 See also 9 Notes 9.1 Footnotes 9.2 Citations 10 References 11 Further reading 12 External links Etymology Main article: New Zealand place names brown square paper with Dutch writing and a thick red, curved line Detail from a 1657 map showing the western coastline of "Nova Zeelandia" Aotearoa (often translated as "land of the long white cloud")[13] is the current Maori name for New Zealand, and is also used in New Zealand English. It is unkn own whether Maori had a name for the whole country before the arrival of Europea ns, with Aotearoa originally referring to just the North Island.[14] Dutch explo rer Abel Tasman sighted New Zealand in 1642 and called it Staten Landt, supposin g it was connected to a landmass of the same name at the southern tip of South A merica.[15] In 1645 Dutch cartographers renamed the land Nova Zeelandia after th e Dutch province of Zeeland.[16][17] British explorer James Cook subsequently an glicised the name to New Zealand.[n 6] Maori had several traditional names for the two main islands, including Te Ika-a -Maui (the fish of Maui) for the North Island and Te Wai Pounamu (the waters of greenstone) or Te Waka o Aoraki (the canoe of Aoraki) for the South Island.[18] Early European maps labelled the islands North (North Island), Middle (South Isl and) and South (Stewart Island / Rakiura).[19] In 1830 maps began to use North a nd South to distinguish the two largest islands and by 1907 this was the accepte d norm.[20] The New Zealand Geographic Board discovered in 2009 that the names o f the North Island and South Island had never been formalised, but there are now plans to do so.[21] The board is also considering suitable Maori names,[22] wit h Te Ika-a-Maui and Te Wai Pounamu the most likely choices according to the chai rman of the Maori Language Commission.[23] History

Main article: History of New Zealand One set of arrows point from Taiwan to Melanesia to Fiji/Samoa and then to the M arquesas Islands. The population then spread, some going south to New Zealand an d others going north to Hawai'i. A second set start in southern Asia and end in Melanesia. The Maori people are most likely descended from people who emigrated from Taiwan to Melanesia and then travelled east through to the Society Islands. After a pa use of 70 to 265 years, a new wave of exploration led to the discovery and settl ement of New Zealand.[24] New Zealand was one of the last major landmasses settled by humans. Radiocarbon dating, evidence of deforestation[25] and mitochondrial DNA variability within M aori populations[26] suggest New Zealand was first settled by Eastern Polynesian s between 1250 and 1300,[18][27] concluding a long series of voyages through the southern Pacific islands.[28] Over the centuries that followed these settlers d eveloped a distinct culture now known as Maori. The population was divided into iwi (tribes) and hapu (subtribes) which would cooperate, compete and sometimes f ight with each other. At some point a group of Maori migrated to the Chatham Isl ands (which they named Rekohu) where they developed their distinct Moriori cultu re.[29][30] The Moriori population was decimated between 1835 and 1862, largely because of Taranaki Maori invasion and enslavement in the 1830s, although Europe an diseases also contributed. In 1862 only 101 survived and the last known fullblooded Moriori died in 1933.[31] The first Europeans known to have reached New Zealand were Dutch explorer Abel T asman and his crew in 1642.[32] In a hostile encounter, four crew members were k illed and at least one Maori was hit by canister shot.[33] Europeans did not rev isit New Zealand until 1769 when British explorer James Cook mapped almost the e ntire coastline.[32] Following Cook, New Zealand was visited by numerous Europea n and North American whaling, sealing and trading ships. They traded food, metal tools, weapons and other goods for timber, food, artefacts, water, and on occas ion sex.[34] The introduction of the potato and the musket transformed Maori agr iculture and warfare. Potatoes provided a reliable food surplus, which enabled l onger and more sustained military campaigns.[35] The resulting inter-tribal Musk et Wars encompassed over 600 battles between 1801 and 1840, killing 30,000 40,000 Maori.[36] From the early 19th century, Christian missionaries began to settle N ew Zealand, eventually converting most of the Maori population.[37] The Maori po pulation declined to around 40 percent of its pre-contact level during the 19th century; introduced diseases were the major factor.[38] A torn sheet of paper The Waitangi sheet from the Treaty of Waitangi The British Government appointed James Busby as British Resident to New Zealand in 1832[39] and in 1835, following an announcement of impending French settlemen t by Charles de Thierry, the nebulous United Tribes of New Zealand sent a Declar ation of the Independence to King William IV of the United Kingdom asking for pr otection.[39] Ongoing unrest and the dubious legal standing of the Declaration o f Independence prompted the Colonial Office to send Captain William Hobson to cl aim sovereignty for the British Crown and negotiate a treaty with the Maori.[40] The Treaty of Waitangi was first signed in the Bay of Islands on 6 February 184 0.[41] In response to the commercially run New Zealand Company's attempts to est ablish an independent settlement in Wellington[42] and French settlers "purchasi ng" land in Akaroa,[43] Hobson declared British sovereignty over all of New Zeal and on 21 May 1840, even though copies of the Treaty were still circulating.[44] With the signing of the Treaty and declaration of sovereignty the number of imm igrants, particularly from the United Kingdom, began to increase.[45] New Zealand, originally part of the colony of New South Wales, became a separate Colony of New Zealand on 1 July 1841.[46] The colony gained a representative go vernment in 1852 and the 1st New Zealand Parliament met in 1854.[47] In 1856 the colony effectively became self-governing, gaining responsibility over all domes tic matters other than native policy. (Control over native policy was granted in

the mid-1860s.)[47] Following concerns that the South Island might form a separ ate colony, premier Alfred Domett moved a resolution to transfer the capital fro m Auckland to a locality near the Cook Strait.[48] Wellington was chosen for its harbour and central location, with parliament officially sitting there for the first time in 1865. As immigrant numbers increased, conflicts over land led to t he New Zealand Wars of the 1860s and 1870s, resulting in the loss and confiscati on of much Maori land.[49] In 1893 the country became the first nation in the wo rld to grant all women the right to vote[50] and in 1894 pioneered the adoption of compulsory arbitration between employers and unions.[51] In 1907, at the request of the New Zealand Parliament, King Edward VII proclaime d New Zealand a dominion within the British Empire, reflecting its self-governin g status. In 1947 the country adopted the Statute of Westminster, confirming tha t the British parliament could no longer legislate for New Zealand without the c onsent of New Zealand.[47] New Zealand was involved in world affairs, fighting a longside the British Empire in the First and Second World Wars[52] and suffering through the Great Depression.[53] The depression led to the election of the fir st Labour government and the establishment of a comprehensive welfare state and a protectionist economy.[54] New Zealand experienced increasing prosperity follo wing World War II[55] and Maori began to leave their traditional rural life and move to the cities in search of work.[56] A Maori protest movement developed, wh ich criticised Eurocentrism and worked for greater recognition of Maori culture and the Treaty of Waitangi.[57] In 1975, a Waitangi Tribunal was set up to inves tigate alleged breaches of the Treaty, and it was enabled to investigate histori c grievances in 1985.[41] The government has negotiated settlements of these gri evances with many iwi, although Maori claims to the foreshore and seabed have pr oved controversial in the 2000s. Politics Main article: Politics of New Zealand A smiling man wearing a white shirt with a green tie and black jacket John Key, Prime Minister of New Zealand since 2008 Government New Zealand is a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary democracy,[58] alt hough its constitution is not codified.[59] Elizabeth II is the Queen of New Zea land and the head of state.[60] The Queen is represented by the Governor-General , whom she appoints on the advice of the Prime Minister.[61][62] The Governor-Ge neral can exercise the Crown's prerogative powers, such as reviewing cases of in justice and making appointments of ministers, ambassadors and other key public o fficials,[63] and in rare situations, the reserve powers (e.g. the power to diss olve Parliament or refuse the Royal Assent of a bill into law).[64] The powers o f the Queen and the Governor-General are limited by constitutional constraints a nd they cannot normally be exercised without the advice of Cabinet.[64][65] refer to caption Elizabeth II refer to caption Sir Jerry Mateparae The Queen of New Zealand and her vice-regal representative, the Governor-General The New Zealand Parliament holds legislative power and consists of the Queen and the House of Representatives.[65] It also included an upper house, the Legislat ive Council, until this was abolished in 1950.[65] The supremacy of Parliament, over the Crown and other government institutions, was established in England by the Bill of Rights 1689 and has been ratified as law in New Zealand.[65] The Hou se of Representatives is democratically elected and a Government is formed from the party or coalition with the majority of seats.[65] If no majority is formed a minority government can be formed if support from other parties during confide nce and supply votes is assured. The Governor-General appoints ministers under a dvice from the Prime Minister, who is by convention the Parliamentary leader of the governing party or coalition.[66] Cabinet, formed by ministers and led by th e Prime Minister, is the highest policy-making body in government and responsibl

e for deciding significant government actions.[67] By convention, members of cab inet are bound by collective responsibility to decisions made by cabinet.[68] Judges and judicial officers are appointed non-politically and under strict rule s regarding tenure to help maintain constitutional independence from the governm ent.[59] This theoretically allows the judiciary to interpret the law based sole ly on the legislation enacted by Parliament without other influences on their de cisions.[69] The Privy Council in London was the country's final court of appeal until 2004, when it was replaced with the newly established Supreme Court of Ne w Zealand. The judiciary, headed by the Chief Justice,[70] includes the Court of Appeal, the High Court, and subordinate courts.[59] A block of buildings fronted by a grassy lawn New Zealand government "Beehive" and the Parliament Buildings (right), in Wellin gton Almost all parliamentary general elections between 1853 and 1993 were held under the first-past-the-post voting system.[71] The elections since 1930 have been d ominated by two political parties, National and Labour.[71] Since the 1996 elect ion, a form of proportional representation called Mixed Member Proportional (MMP ) has been used.[59] Under the MMP system each person has two votes; one is for electoral seats (including some reserved for Maori),[72] and the other is for a party. Since the 2005 election, there have been 70 electorate seats (which inclu des, since the 1996 election, 7 Maori electorates), and the remaining fifty seat s are assigned so that representation in parliament reflects the party vote, alt hough a party has to win one electoral seat or 5 percent of the total party vote before it is eligible for these seats.[73] Between March 2005 and August 2006 N ew Zealand became the only country in the world in which all the highest offices in the land (Head of State, Governor-General, Prime Minister, Speaker and Chief Justice) were occupied simultaneously by women.[74] New Zealand is identified as one of the world's most stable and well-governed na tions.[75] As of 2011, the country was ranked 5th in the strength of its democra tic institutions[76] and 1st in government transparency and lack of corruption.[ 77] New Zealand has a high level of civic participation, with 79% voter turnout during the most recent elections, compared to an OECD average of 72%. Furthermor e, 67% of New Zealanders say they trust their political institutions, far higher than the OECD average of 56%.[78] See also: International rankings of New Zealand Foreign relations and the military Main articles: Foreign relations of New Zealand and New Zealand Defence Force Anzac Day service at the National War Memorial Early colonial New Zealand allowed the British Government to determine external trade and be responsible for foreign policy.[79] The 1923 and 1926 Imperial Conf erences decided that New Zealand should be allowed to negotiate their own politi cal treaties, with the first successful commercial treaty being with Japan in 19 28. Despite this independence New Zealand readily followed Britain in declaring war on Germany on 3 September 1939 with then Prime Minister Michael Savage procl aiming, "Where she goes, we go; where she stands, we stand."[80] A squad of men kneel in the desert sand while performing a war dance Maori Battalion haka in Egypt, 1941 In 1951 the United Kingdom became increasingly focused on its European interests ,[81] while New Zealand joined Australia and the United States in the ANZUS secu rity treaty.[82] The influence of the United States on New Zealand weakened foll owing protests over the Vietnam War,[83] the refusal of the United States to adm onish France after the sinking of the Rainbow Warrior,[84] disagreements over en vironmental and agricultural trade issues and New Zealand's nuclear-free policy. [85][86] Despite the USA's suspension of ANZUS obligations the treaty remained i n effect between New Zealand and Australia, whose foreign policy has followed a similar historical trend.[87] Close political contact is maintained between the

two countries, with free trade agreements and travel arrangements that allow cit izens to visit, live and work in both countries without restrictions.[88] Curren tly over 500,000 New Zealanders live in Australia and 65,000 Australians live in New Zealand.[88] New Zealand has a strong presence among the Pacific Island countries. A large pr oportion of New Zealand's aid goes to these countries and many Pacific people mi grate to New Zealand for employment.[89] Permanent migration is regulated under the 1970 Samoan Quota Scheme and the 2002 Pacific Access Category, which allow u p to 1,100 Samoan nationals and up to 750 other Pacific Islanders respectively t o become permanent New Zealand residents each year. A seasonal workers scheme fo r temporary migration was introduced in 2007 and in 2009 about 8,000 Pacific Isl anders were employed under it.[90] New Zealand is involved in the Pacific Island s Forum, Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation and the Association of Southeast Asia n Nations Regional Forum (including the East Asia Summit).[88] New Zealand is al so a member of the United Nations,[91] the Commonwealth of Nations,[92] the Orga nisation for Economic Co-operation and Development[93] and the Five Power Defenc e Arrangements.[94] Infantry from the 2nd Battalion, Auckland Regiment in the Battle of the Somme, S eptember 1916. The New Zealand Defence Force has three branches: the Royal New Zealand Navy, th e New Zealand Army and the Royal New Zealand Air Force.[95] New Zealand's nation al defence needs are modest because of the unlikelihood of direct attack,[96] al though it does have a global presence. The country fought in both world wars, wi th notable campaigns in Gallipoli, Crete,[97] El Alamein[98] and Cassino.[99] Th e Gallipoli campaign played an important part in fostering New Zealand's nationa l identity[100][101] and strengthened the ANZAC tradition it shares with Austral ia.[102] According to Mary Edmond-Paul, "World War I had left scars on New Zeala nd society, with nearly 18,500 in total dying as a result of the war, more than 41,000 wounded, and others affected emotionally, out of an overseas fighting for ce of about 103,000 and a population of just over a million."[103] New Zealand a lso played key parts in the naval Battle of the River Plate[104] and the Battle of Britain air campaign.[105][106] During World War II, the United States had mo re than 400,000 American military personnel stationed in New Zealand.[107] In addition to Vietnam and the two world wars, New Zealand fought in the Korean War, the Second Boer War,[108] the Malayan Emergency,[109] the Gulf War and the Afghanistan War. It has contributed forces to several regional and global peacek eeping missions, such as those in Cyprus, Somalia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, the S inai, Angola, Cambodia, the Iran Iraq border, Bougainville, East Timor, and the So lomon Islands.[110] New Zealand also sent a unit of army engineers to help rebui ld Iraqi infrastructure for one year during the Iraq War. New Zealand ranks 8th in the Center for Global Development's 2012 Commitment to Development Index, which ranks the world's most developed countries on their ded ication to policies that benefit poorer nations.[111] New Zealand is considered the second most peaceful country in the world according to the 2012 Global Peace Index.[112] Local government and external territories Main articles: Local government in New Zealand and Realm of New Zealand Realm of New Zealand The early European settlers divided New Zealand into provinces, which had a degr ee of autonomy.[113] Because of financial pressures and the desire to consolidat e railways, education, land sales and other policies, government was centralised and the provinces were abolished in 1876.[114] As a result, New Zealand now has no separately represented subnational entities. The provinces are remembered in regional public holidays[115] and sporting rivalries.[116] Since 1876, various councils have administered local areas under legislation det ermined by the central government.[113][117] In 1989, the government reorganised

local government into the current two-tier structure of regional councils and t erritorial authorities.[118] The 249 municipalities[118] that existed in 1975 ha ve now been consolidated into 67 territorial authorities and 11 regional council s.[119] The regional councils' role is to regulate "the natural environment with particular emphasis on resource management",[118] while territorial authorities are responsible for sewage, water, local roads, building consents and other loc al matters.[120] Five of the territorial councils are unitary authorities and al so act as regional councils.[121] The territorial authorities consist of 13 city councils, 53 district councils, and the Chatham Islands Council. While official ly the Chatham Islands Council is not a unitary authority, it undertakes many fu nctions of a regional council.[122] The Realm of New Zealand is one of 16 realms within the commonwealth[123][124] a nd comprises New Zealand, Tokelau, the Ross Dependency, the Cook Islands and Niu e.[124] The Cook Islands and Niue are self-governing states in free association with New Zealand.[125][126] The New Zealand Parliament cannot pass legislation f or these countries, but with their consent can act on behalf of them in foreign affairs and defence. Tokelau is a non-self-governing territory that uses the New Zealand flag and anthem, but is administered by a council of three elders (one from each Tokelauan atoll).[127][128] The Ross Dependency is New Zealand's terri torial claim in Antarctica, where it operates the Scott Base research facility.[ 129] New Zealand citizenship law treats all parts of the realm equally, so most people born in New Zealand, the Cook Islands, Niue, Tokelau and the Ross Depende ncy before 2006 are New Zealand citizens. Further conditions apply for those bor n from 2006 onwards.[130] [show] v t e Administrative divisions of New Zealand Environment Main article: Environment of New Zealand Geography Main article: Geography of New Zealand See also: Atlas of New Zealand at Wikimedia Commons Photo of New Zealand from space. The snow-capped Southern Alps dominate the South Island, while the North Island' s Northland Peninsula stretches towards the subtropics. Aoraki / Mount Cook viewed from the road to Mount Cook Village, located in the S outhern Alps. A significant portion of New Zealand's South Island landscape is m ountainous. Photo showing clear blue water, a photographer or tourist capturing the water on a golden sanded beach and forested hills Torrent Bay at Abel Tasman National Park in the South Island New Zealand is made up of two main islands and a number of smaller islands, loca ted near the centre of the water hemisphere. The main North and South Islands ar e separated by the Cook Strait, 22 kilometres (14 mi) wide at its narrowest poin t.[131] Besides the North and South Islands, the five largest inhabited islands are Stewart Island, the Chatham Islands, Great Barrier Island (in the Hauraki Gu lf),[132] d'Urville Island (in the Marlborough Sounds)[133] and Waiheke Island ( about 22 km (14 mi) from central Auckland).[134] The country's islands lie betwe en latitudes 29 and 53S, and longitudes 165 and 176E. New Zealand is long (over 1,600 kilometres (990 mi) along its north-north-east a xis) and narrow (a maximum width of 400 kilometres (250 mi)),[135] with approxim ately 15,000 km (9,300 mi) of coastline[136] and a total land area of 268,000 sq uare kilometres (103,500 sq mi)[137] Because of its far-flung outlying islands a nd long coastline, the country has extensive marine resources. Its Exclusive Eco nomic Zone, one of the largest in the world, covers more than 15 times its land area.[138] The South Island is the largest land mass of New Zealand, and is divided along i

ts length by the Southern Alps.[139] There are 18 peaks over 3,000 metres (9,800 ft), the highest of which is Aoraki / Mount Cook at 3,754 metres (12,316 ft).[1 40] Fiordland's steep mountains and deep fiords record the extensive ice age gla ciation of this south-western corner of the South Island.[141] The North Island is less mountainous but is marked by volcanism.[142] The highly active Taupo Vol canic Zone has formed a large volcanic plateau, punctuated by the North Island's highest mountain, Mount Ruapehu (2,797 metres (9,177 ft)). The plateau also hos ts the country's largest lake, Lake Taupo,[143] nestled in the caldera of one of the world's most active supervolcanoes.[144] The country owes its varied topography, and perhaps even its emergence above the waves, to the dynamic boundary it straddles between the Pacific and Indo-Austra lian Plates.[145] New Zealand is part of Zealandia, a microcontinent nearly half the size of Australia that gradually submerged after breaking away from the Gon dwanan supercontinent.[146] About 25 million years ago, a shift in plate tectoni c movements began to contort and crumple the region. This is now most evident in the Southern Alps, formed by compression of the crust beside the Alpine Fault. Elsewhere the plate boundary involves the subduction of one plate under the othe r, producing the Puysegur Trench to the south, the Hikurangi Trench east of the North Island, and the Kermadec and Tonga Trenches[147] further north.[145] Climate Main article: Climate of New Zealand New Zealand has a mild and temperate maritime climate (Kppen: Cfb) with mean annu al temperatures ranging from 10 C (50 F) in the south to 16 C (61 F) in the north.[1 48] Historical maxima and minima are 42.4 C (108.32 F) in Rangiora, Canterbury and -25.6 C (-14.08 F) in Ranfurly, Otago.[149] Conditions vary sharply across region s from extremely wet on the West Coast of the South Island to almost semi-arid i n Central Otago and the Mackenzie Basin of inland Canterbury and subtropical in Northland.[150] Of the seven largest cities, Christchurch is the driest, receivi ng on average only 640 millimetres (25 in) of rain per year and Auckland the wet test, receiving almost twice that amount.[151] Auckland, Wellington and Christch urch all receive a yearly average in excess of 2,000 hours of sunshine. The sout hern and south-western parts of the South Island have a cooler and cloudier clim ate, with around 1,400 1,600 hours; the northern and north-eastern parts of the So uth Island are the sunniest areas of the country and receive approximately 2,400 2 ,500 hours.[152] The general snow season is about early June until early October in the South Island. It is less common on the North Island, although it does oc cur. Biodiversity Main article: Biodiversity of New Zealand New Zealand's geographic isolation for 80 million years[153] and island biogeogr aphy is responsible for the country's unique species of animals, fungi and plant s. They have either evolved from Gondwanan wildlife or the few organisms that ha ve managed to reach the shores flying, swimming or being carried across the sea. [154] About 82 percent of New Zealand's indigenous vascular plants are endemic, covering 1,944 species across 65 genera and includes a single family.[155][156] The number of fungi recorded from New Zealand, including lichen-forming species, is not known, nor is the proportion of those fungi which are endemic, but one e stimate suggests there are approximately 2300 species of lichen-forming fungi in New Zealand[155] and 40 percent of these are endemic.[157] The two main types o f forest are those dominated by broadleaf trees with emergent podocarps, or by s outhern beech in cooler climates.[158] The remaining vegetation types consist of grasslands, the majority of which are tussock.[159] Before the arrival of humans an estimated 80 percent of the land was covered in forest, with only high alpine, wet, infertile and volcanic areas without trees.[ 160] Massive deforestation occurred after humans arrived, with around half the f orest cover lost to fire after Polynesian settlement.[161] Much of the remaining forest fell after European settlement, being logged or cleared to make room for pastoral farming, leaving forest occupying only 23 percent of the land.[162] Kiwi amongst sticks

The endemic flightless kiwi is a national icon. The forests were dominated by birds, and the lack of mammalian predators led to some like the kiwi, kakapo and takahe evolving flightlessness.[163] The arrival of humans, associated changes to habitat, and the introduction of rats, ferrets and other mammals led to the extinction of many bird species, including large bi rds like the moa and Haast's Eagle.[164][165] Other indigenous animals are represented by reptiles (tuataras, skinks and gecko s),[166] frogs, spiders (katipo), insects (weta) and snails.[167][168] Some, suc h as the wrens and tuatara, are so unique that they have been called living foss ils. Three species of bats (one since extinct) were the only sign of native land mammals in New Zealand until the 2006 discovery of bones from a unique, mouse-s ized land mammal at least 16 million years old.[169][170] Marine mammals however are abundant, with almost half the world's cetaceans (whales, dolphins, and por poises) and large numbers of fur seals reported in New Zealand waters.[171] Many seabirds breed in New Zealand, a third of them unique to the country.[172] More penguin species are found in New Zealand than in any other country.[173] Since human arrival almost half of the country's vertebrate species have become extinct, including at least fifty-one birds, three frogs, three lizards, one fre shwater fish, and one bat. Others are endangered or have had their range severel y reduced.[164] However, New Zealand conservationists have pioneered several met hods to help threatened wildlife recover, including island sanctuaries, pest con trol, wildlife translocation, fostering, and ecological restoration of islands a nd other selected areas.[174][175][176][177] According to the 2012 Environmental Performance Index, New Zealand is considered a "strong performer" in environmen tal protection, ranking 14th out of 132 assessed countries.[178] Economy Main article: Economy of New Zealand See also: List of companies of New Zealand and Transport in New Zealand New Zealand has a modern, prosperous and developed market economy with an estima ted gross domestic product (GDP) at purchasing power parity (PPP) per capita of roughly US$28,250.[n 7] The currency is the New Zealand dollar, informally known as the "Kiwi dollar"; it also circulates in the Cook Islands (see Cook Islands dollar), Niue, Tokelau, and the Pitcairn Islands.[182] New Zealand was ranked 5t h in the 2011 Human Development Index,[183] 4th in the The Heritage Foundation's 2012 Index of Economic Freedom,[184] and 13th in INSEAD's 2012 Global Innovatio n Index.[185] Blue water against a backdrop of snow capped mountains Milford Sound, one of New Zealand's most famous tourist destinations.[186] Historically, extractive industries have contributed strongly to New Zealand's e conomy, focussing at different times on sealing, whaling, flax, gold, kauri gum, and native timber.[187] With the development of refrigerated shipping in the 18 80s meat and dairy products were exported to Britain, a trade which provided the basis for strong economic growth in New Zealand.[188] High demand for agricultu ral products from the United Kingdom and the United States helped New Zealanders achieve higher living standards than both Australia and Western Europe in the 1 950s and 1960s.[189] In 1973 New Zealand's export market was reduced when the Un ited Kingdom joined the European Community[190] and other compounding factors, s uch as the 1973 oil and 1979 energy crisis, led to a severe economic depression. [191] Living standards in New Zealand fell behind those of Australia and Western Europe, and by 1982 New Zealand had the lowest per-capita income of all the dev eloped nations surveyed by the World Bank.[192] Since 1984, successive governmen ts engaged in major macroeconomic restructuring (known first as Rogernomics and then Ruthanasia), rapidly transforming New Zealand from a highly protectionist e conomy to a liberalised free-trade economy.[193][194] Unemployment peaked above 10 percent in 1991 and 1992,[195] following the 1987 s hare market crash, but eventually fell to a record low of 3.4 percent in 2007 (r anking fifth from twenty-seven comparable OECD nations).[196] However, the globa l financial crisis that followed had a major impact on New Zealand, with the GDP

shrinking for five consecutive quarters, the longest recession in over thirty y ears,[197][198] and unemployment rising back to 7% in late 2009.[199] As of May 2012, the general unemployment rate was around 6.7%, while the unemployment rate for youth aged 15 to 21 was 13.6%.[200] New Zealand has experienced a series of "brain drains" since the 1970s[201] that still continue today.[202] Nearly one quarter of highly skilled workers live overseas, mostly in Australia and Britain , which is the largest proportion from any developed nation.[203] In recent year s, however, a "brain gain" has brought in educated professionals from Europe and lesser developed countries.[204][205] Trade New Zealand is heavily dependent on international trade,[206] particularly in ag ricultural products.[207] Exports account for a high 24 percent of its output,[1 36] making New Zealand vulnerable to international commodity prices and global e conomic slowdowns. Its principal export industries are agriculture, horticulture , fishing, forestry and mining, which make up about half of the country's export s.[208] Its major export partners are Australia, United States, Japan, China, an d the United Kingdom.[136] On 7 April 2008, New Zealand and China signed the New Zealand China Free Trade Agreement, the first such agreement China has signed wit h a developed country.[209][210] The service sector is the largest sector in the economy, followed by manufacturing and construction and then farming and raw ma terial extraction.[136] Tourism plays a significant role in New Zealand's econom y, contributing $15.0 billion to New Zealand s total GDP and supporting 9.6 percen t of the total workforce in 2010.[211] International visitors to New Zealand inc reased by 3.1 percent in the year to October 2010[212] and are expected to incre ase at a rate of 2.5 percent annually up to 2015.[211] A Romney ewe with her two lambs Wool has historically been one of New Zealand's major exports. Wool was New Zealand s major agricultural export during the late 19th century.[187 ] Even as late as the 1960s it made up over a third of all export revenues,[187] but since then its price has steadily dropped relative to other commodities[213 ] and wool is no longer profitable for many farmers.[214] In contrast dairy farm ing increased, with the number of dairy cows doubling between 1990 and 2007,[215 ] to become New Zealand's largest export earner.[216] In the year to June 2009, dairy products accounted for 21 percent ($9.1 billion) of total merchandise expo rts,[217] and the country's largest company, Fonterra, controls almost one-third of the international dairy trade.[218] Other agricultural exports in 2009 were meat 13.2 percent, wool 6.3 percent, fruit 3.5 percent and fishing 3.3 percent. New Zealand's wine industry has followed a similar trend to dairy, the number of vineyards doubling over the same period,[219] overtaking wool exports for the f irst time in 2007.[220][221] Infrastructure In 2008, oil, gas and coal generated approximately 69 percent of New Zealand's g ross energy supply and 31% was generated from renewable energy, primarily hydroe lectric power and geothermal power.[222] New Zealand's transport network include s 93,805 kilometres (58,288 mi) of roads, worth 23 billion dollars,[223] and 4,1 28 kilometres (2,565 mi) of railway lines.[136] Most major cities and towns are linked by bus services, although the private car is the predominant mode of tran sport.[224] The railways were privatised in 1993, then re-purchased by the gover nment in 2004 and vested into a state owned enterprise.[225] Railways run the le ngth of the country, although most lines now carry freight rather than passenger s.[226] Most international visitors arrive via air[227] and New Zealand has six international airports, although currently only the Auckland and Christchurch ai rports connect directly with countries other than Australia or Fiji.[228] The Ne w Zealand Post Office had a monopoly over telecommunications until 1989 when Tel ecom New Zealand was formed, initially as a state-owned enterprise and then priv atised in 1990.[229] Telecom still owns the majority of the telecommunications i nfrastructure, but competition from other providers has increased.[230] The Unit ed Nations International Telecommunication Union ranks New Zealand 12th in the d evelopment of information and communications infrastructure, having moved up fou

r places between 2008 and 2010.[231] Demography Main article: Demographics of New Zealand Graph with a New Zealand population scale ranging from 0 to almost 7 million on the y axis and the years from 1850 to around 2070 on the x axis. A black line st arts at about 100,000 in 1858 and increases steadily to about 4.1 million in 200 6. Seven separate red lines then project out from the black line ending in value s ranging from roughly 4.5 to 6.5 million in the year 2061; two lines are slight ly thicker than the rest. New Zealand's historical population (black) and projected growth (red) The population of New Zealand is approximately 4.5 million.[232] New Zealand is a predominantly urban country, with 72 percent of the population living in 16 ma in urban areas and 53 percent living in the four largest cities of Auckland, Chr istchurch, Wellington, and Hamilton.[233] New Zealand cities generally rank high ly on international livability measures. For instance, in 2010 Auckland was rank ed the world's 4th most liveable city and Wellington the 12th by the Mercer Qual ity of Life Survey[234] The life expectancy of a New Zealand child born in 2008 was 82.4 years for femal es, and 78.4 years for males.[235] Life expectancy at birth is forecast to incre ase from 80 years to 85 years in 2050 and infant mortality is expected to declin e.[236] New Zealand's fertility rate of 2.1 is relatively high for a developed c ountry, and natural births account for a significant proportion of population gr owth. Subsequently, the country has a young population compared to most industri alized nations, with 20 percent of New Zealanders being 14 years-old or younger. [136] By 2050 the population is forecast to reach 5.3 million, the median age to rise from 36 years to 43 years and the percentage of people 60 years of age and older to rise from 18 percent to 29 percent.[236] Ethnicity and immigration Main articles: New Zealanders and Immigration to New Zealand New Zealanders of European descent In the 2006 census, 67.6 percent identified ethnically as European and 14.6 perc ent as Maori.[237] Other major ethnic groups include Asian (9.2 percent) and Pac ific peoples (6.9 percent), while 11.1 percent identified themselves simply as a "New Zealander" (or similar) and 1 percent identified with other ethnicities.[2 38][n 8] This contrasts with 1961, when the census reported that the population of New Zealand was 92 percent European and 7 percent Maori, with Asian and Pacif ic minorities sharing the remaining 1 percent.[240] While the demonym for a New Zealand citizen is New Zealander, the informal "Kiwi" is commonly used both inte rnationally[241] and by locals.[242] The Maori loanword Pakeha has been used to refer to New Zealanders of European descent, although others reject this appella tion.[243][244] The word Pakeha today is increasingly used to refer to all non-P olynesian New Zealanders.[245] Lion dancers wearing bright red and yellow costumes lion dancers perform at the Auckland Lantern Festival. The Maori were the first people to reach New Zealand, followed by the early Euro pean settlers. Following colonisation, immigrants were predominantly from Britai n, Ireland and Australia because of restrictive policies similar to the white Au stralian policies.[246] There was also significant Dutch, Dalmatian,[247] Italia n, and German immigration, together with indirect European immigration through A ustralia, North America, South America and South Africa.[248] Following the Grea t Depression policies were relaxed and migrant diversity increased. In 2009 10, an annual target of 45,000 50,000 permanent residence approvals was set by the New Z ealand Immigration Service more than one new migrant for every 100 New Zealand r esidents.[249] Twenty-three percent of New Zealand's population were born overse as, most of whom live in the Auckland region.[250] While most have still come fr

om the United Kingdom and Ireland (29 percent), immigration from East Asia (most ly mainland China, but with substantial numbers also from Korea, Taiwan, Japan, and Hong Kong) is rapidly increasing the number of people from those countries.[ 251] The number of fee-paying international students increased sharply in the la te 1990s, with more than 20,000 studying in public tertiary institutions in 2002 .[252] Language Main article: Languages of New Zealand English is the predominant language in New Zealand, spoken by 98 percent of the population.[3] New Zealand English is similar to Australian English and many spe akers from the Northern Hemisphere are unable to tell the accents apart.[253]. T he most prominent differences between the New Zealand English dialect and other English dialects are the shifts in the short front vowels: the short-"i" sound ( as in "kit") has centralised towards the schwa sound (the "a" in "comma" and "ab out"); the short-"e" sound (as in "dress") has moved towards the short-"i" sound ; and the short-"a" sound (as in "trap") has moved to the short-"e" sound.[254] Hence, the New Zealand pronunciation of words such as "bad", "dead", "fish" and "chips" sound like "bed", "did", "fush" and "chups" to non-New Zealanders. After the Second World War, Maori were discouraged from speaking their own langu age (te reo Maori) in schools and workplaces and it existed as a community langu age only in a few remote areas.[255] It has recently undergone a process of revi talisation,[256][257] being declared one of New Zealand's official languages in 1987,[258] and is spoken by 4.1 percent of the population.[3] There are now Maor i language immersion schools and two Maori Television channels, the only nationw ide television channels to have the majority of their prime-time content deliver ed in Maori.[259] Many places have officially been given dual Maori and English names in recent years. Samoan is one of the most widely spoken languages in New Zealand (2.3 percent),[n 9] followed by French, Hindi, Yue and Northern Chinese. [3][260][n 10] New Zealand Sign Language is used by approximately 28,000 people and was declared one of New Zealand's official languages in 2006.[261] Simple white building with two red domed towers A Ratana church Education and religion Main articles: Education in New Zealand and Religion in New Zealand Primary and secondary schooling is compulsory for children aged 6 to 16, with th e majority attending from the age of 5.[262] There are 13 school years and atten ding state (public) schools is free to New Zealand citizens and permanent reside nts from a person's 5th birthday to the end of the calendar year following their 19th birthday.[263] New Zealand has an adult literacy rate of 99 percent,[136] and over half of the population aged 15 to 29 hold a tertiary qualification.[262 ][n 11] There are five types of government-owned tertiary institutions: universi ties, colleges of education, polytechnics, specialist colleges, and wananga,[264 ] in addition to private training establishments.[265] In the adult population 1 4.2 percent have a bachelor's degree or higher, 30.4 percent have some form of s econdary qualification as their highest qualification and 22.4 percent have no f ormal qualification.[266] The OECD's Programme for International Student Assessm ent ranks New Zealand's education system as the 7th best in the world, with stud ents performing exceptionally well in reading, mathematics and science.[267] Christianity is the predominant religion in New Zealand, although its society is among the most secular in the world.[268] In the 2006 Census, 55.6 percent of t he population identified themselves as Christians, while another 34.7 percent in dicated that they had no religion (up from 29.6 percent in 2001) and around 4 pe rcent affiliated with other religions.[269][n 12] The main Christian denominatio ns are Anglicanism, Roman Catholicism, Presbyterianism and Methodism. There are also significant numbers of Christians who identify themselves with Pentecostal, Baptist, and Latter-day Saint churches and the New Zealand-based Ratana church has adherents among Maori. According to census figures, other significant minori ty religions include Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam.[260][270]

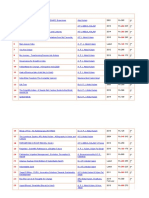

List of cities in New Zealand (June 2010 population estimates)[271] Map of New Zealand, with cities labelled . Rank City Name Region Pop. Rank City Name Region Pop. 1 Auckland Auckland Region 1,397,300 7 Dunedin Otago Re gion 118,400 2 Wellington Wellington Region 395,600 8 Palmerston North Manawatu-Wanganui Region 83,300 3 Christchurch Canterbury Region 375,900 9 Nelson Nelson 61,100 4 Hamilton Waikato Region 209,300 10 Rotorua Bay of Plenty Re gion 56,100 5 Napier-Hastings Hawke's Bay Region 125,000 11 New Plymouth Taranaki Region 53,000 6 Tauranga Bay of Plenty Region 122,200 12 Whangarei Northland Region 52,500 Culture Main article: Culture of New Zealand Tall wooden carving showing Kupe above two tentacled sea creatures Late twentieth-century house-post depicting the navigator Kupe fighting two sea creatures Early Maori adapted the tropically based east Polynesian culture in line with th e challenges associated with a larger and more diverse environment, eventually d eveloping their own distinctive culture. Social organisation was largely communa l with families (whanau), sub-tribes (hapu) and tribes (iwi) ruled by a chief (r angatira) whose position was subject to the community's approval.[272] The Briti sh and Irish immigrants brought aspects of their own culture to New Zealand and also influenced Maori culture,[273][274] particularly with the introduction of C hristianity.[275] However, Maori still regard their allegiance to tribal groups as a vital part of their identity, and Maori kinship roles resemble those of oth er Polynesian peoples.[276] More recently American, Australian, Asian and other European cultures have exerted influence on New Zealand. Non-Maori Polynesian cu ltures are also apparent, with Pasifika, the world's largest Polynesian festival , now an annual event in Auckland. Two women in long flowing yellow skirts either side of a man in a short black sk irt mid dance Cook Islands dancers at Auckland's Pasifika festival The largely rural life in early New Zealand led to the image of New Zealanders b eing rugged, industrious problem solvers.[277] Modesty was expected and enforced through the "tall poppy syndrome", where high achievers received harsh criticis m.[278] At the time New Zealand was not known as an intellectual country.[279] F rom the early 20th century until the late 1960s Maori culture was suppressed by the attempted assimilation of Maori into British New Zealanders.[255] In the 196 0s, as higher education became more available and cities expanded[280] urban cul ture began to dominate.[281] Even though the majority of the population now live s in cities, much of New Zealand's art, literature, film and humour has rural th emes. Art Main article: New Zealand art As part of the resurgence of Maori culture, the traditional crafts of carving an d weaving are now more widely practised and Maori artists are increasing in numb er and influence.[282] Most Maori carvings feature human figures, generally with three fingers and either a natural-looking, detailed head or a grotesque head.[ 283] Surface patterns consisting of spirals, ridges, notches and fish scales dec orate most carvings.[284] The pre-eminent Maori architecture consisted of carved meeting houses (wharenui) decorated with symbolic carvings and illustrations. T hese buildings were originally designed to be constantly rebuilt, changing and a

dapting to different whims or needs.[285] Maori decorated the white wood of buildings, canoes and cenotaphs using red (a m ixture of red ochre and shark fat) and black (made from soot) paint and painted pictures of birds, reptiles and other designs on cave walls.[286] Maori tattoos (moko) consisting of coloured soot mixed with gum were cut into the flesh with a bone chisel.[287] Since European arrival paintings and photographs have been do minated by landscapes, originally not as works of art but as factual portrayals of New Zealand.[288] Portraits of Maori were also common, with early painters of ten portraying them as "noble savages", exotic beauties or friendly natives.[288 ] The country's isolation delayed the influence of European artistic trends allo wing local artists to developed their own distinctive style of regionalism.[289] During the 1960s and 70s many artists combined traditional Maori and Western te chniques, creating unique art forms.[290] New Zealand art and craft has graduall y achieved an international audience, with exhibitions in the Venice Biennale in 2001 and the "Paradise Now" exhibition in New York in 2004.[282][291] Refer to caption Portrait of Hinepare of Ngati Kahungunu by Gottfried Lindauer, showing chin moko , pounamu hei-tiki and woven cloak Maori cloaks are made of fine flax fibre and patterned with black, red and white triangles, diamonds and other geometric shapes.[292] Greenstone was fashioned i nto earrings and necklaces, with the most well-known design being the hei-tiki, a distorted human figure sitting cross-legged with its head tilted to the side.[ 293] Europeans brought English fashion etiquette to New Zealand, and until the 1 950s most people dressed up for social occasions.[294] Standards have since rela xed and New Zealand fashion has received a reputation for being casual, practica l and lacklustre.[295][296] However, the local fashion industry has grown signif icantly since 2000, doubling exports and increasing from a handful to about 50 e stablished labels, with some labels gaining international recognition.[296] Literature Main article: New Zealand literature Maori quickly adopted writing as a means of sharing ideas, and many of their ora l stories and poems were converted to the written form.[297] Most early English literature was obtained from Britain and it was not until the 1950s when local p ublishing outlets increased that New Zealand literature started to become widely known.[298] Although still largely influenced by global trends (modernism) and events (the Great Depression), writers in the 1930s began to develop stories inc reasingly focused on their experiences in New Zealand. During this period litera ture changed from a journalistic activity to a more academic pursuit.[299] Parti cipation in the world wars gave some New Zealand writers a new perspective on Ne w Zealand culture and with the post-war expansion of universities local literatu re flourished.[300] Entertainment Main articles: Music of New Zealand, Cinema of New Zealand, and Media of New Zea land Bungee jumping in the popular resort town of Queenstown. New Zealand music has been influenced by blues, jazz, country, rock and roll and hip hop, with many of these genres given a unique New Zealand interpretation.[3 01] Maori developed traditional chants and songs from their ancient South-East A sian origins, and after centuries of isolation created a unique "monotonous" and "doleful" sound.[302] Flutes and trumpets were used as musical instruments[303] or as signalling devices during war or special occasions.[304] Early settlers b rought over their ethnic music, with brass bands and choral music being popular, and musicians began touring New Zealand in the 1860s.[305][306] Pipe bands beca me widespread during the early 20th century.[307] The New Zealand recording indu stry began to develop from 1940 onwards and many New Zealand musicians have obta ined success in Britain and the USA.[301] Some artists release Maori language so ngs and the Maori tradition-based art of kapa haka (song and dance) has made a r

esurgence.[308] The New Zealand Music Awards are held annually by the Recording Industry Association of New Zealand (RIANZ); the awards were first held in 1965 by Reckitt & Colman as the Loxene Golden Disc awards.[309] The RIANZ also publis hes the country's official weekly record charts.[310] Radio first arrived in New Zealand in 1922 and television in 1960.[311] The numb er of New Zealand films significantly increased during the 1970s.[312] In 1978 t he New Zealand Film Commission started assisting local film-makers and many film s attained a world audience, some receiving international acknowledgement. Dereg ulation in the 1980s saw a sudden increase in the numbers of radio and televisio n stations.[312] New Zealand television primarily broadcasts American and Britis h programming, along with a large number of Australian and local shows. The coun try's diverse scenery and compact size, plus government incentives,[313] have en couraged some producers to film big budget movies in New Zealand.[314] The New Z ealand media industry is dominated by a small number of companies, most of which are foreign-owned, although the state retains ownership of some television and radio stations. Between 2003 and 2008, Reporters Without Borders consistently ra nked New Zealand's press freedom in the top twenty.[315] As of 2011, New Zealand was ranked 13th worldwide in press freedom by Freedom House, with the 2nd frees t media in the Asia-Pacific region after Palau.[316] Sports Main article: Sport in New Zealand The Basin Reserve in Wellington, one of the premier cricket grounds in New Zeala nd. Most of the major sporting codes played in New Zealand have English origins.[317 ] Golf, netball, tennis and cricket are the four top participatory sports, socce r is the most popular among young people and rugby union attracts the most spect ators.[318] Victorious rugby tours to Australia and the United Kingdom in the la te 1880s and the early 1900s played an early role in instilling a national ident ity,[319] although the sport's influence has since declined.[320] Horseracing wa s also a popular spectator sport and became part of the "Rugby, Racing and Beer" culture during the 1960s.[321] Maori participation in European sports was parti cularly evident in rugby and the country's team performs a haka (traditional Mao ri challenge) before international matches.[322] New Zealand has competitive international teams in rugby union, netball, cricket , rugby league, and softball and has traditionally done well in triathlons, rowi ng, yachting and cycling. The country has performed well on a medals-to-populati on ratio at Olympic Games and Commonwealth Games.[318][323] New Zealand's nation al rugby union team is often regarded as the best in the world, and are the reig ning World Cup holders. New Zealand are also the reigning rugby league world cha mpions. New Zealand is known for its extreme sports, adventure tourism[324] and strong mountaineering tradition.[325] Other outdoor pursuits such as cycling, fi shing, swimming, running, tramping, canoeing, hunting, snowsports and surfing ar e also popular.[326] The Polynesian sport of waka ama racing has increased in po pularity and is now an international sport involving teams from all over the Pac ific.[327] See also Portal icon New Zealand portal Portal icon Oceania portal List of New Zealand-related topics Outline of New Zealand Notes Footnotes ^ "God Save the Queen" is officially a national anthem but is generally used onl y on regal and vice-regal occasions.[1][2] ^ Language percentages add to more than 100% because some people speak more than one language. They exclude unusable responses and those who spoke no language (

e.g. too young to talk).[3] ^ Ethnicity percentages add to more than 100% because some people identify with more than one ethnic group.[4] ^ The proportion of New Zealand's area (excluding estuaries) covered by rivers, lakes and ponds, based on figures from the New Zealand Land Cover Database,[6] i s (357526 + 81936) / (26821559 92499 26033 19216) = 1.6%. If estuarine open water, mangroves, and herbaceous saline vegetation are included, the figure is 2.2%. ^ The Chatham Islands have a separate time zone, 45 minutes ahead of the rest of New Zealand. ^ Zeeland is spelt "Zealand" in English. New Zealand's name is not derived from the Danish island Zealand. ^ PPP GDP estimates from different organisations vary. The International Monetar y Fund's estimate is US$27,420.[179] The CIA World Factbook estimate is $28,000. [180] The World Bank's estimate is US$29,352.[181] ^ When completing the census people could select more than one ethnic group (for instance, 53 percent of Maori identified solely as Maori, while the remainder a lso identified with one or more other ethnicities).[239] ^ Of the 85,428 people that replied they spoke Samoan in the 2006 Census, 57,828 lived in the Auckland region.[260] ^ Languages listed here are those spoken by over 40,000 New Zealanders. ^ Tertiary education in New Zealand is used to describe all aspects of post-scho ol education and training. Its ranges from informal non-assessed community cours es in schools through to undergraduate degrees and advanced, research-based post graduate degrees. ^ Another 6 percent objected to stating their religion. Statistics NZ do not rep ort a total percentage for "Other" religions. Depending on how many people claim ed both Christian and other religions, this could range from 3 to 5 percent. The se percentages are based on the usually resident population, excluding another 7 percent of people who did not provide usable information. Citations ^ "New Zealand's National Anthems". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 17 February 2008. ^ "Protocol for using New Zealand's National Anthems". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 17 February 2008. ^ a b c d "QuickStats About Culture and Identity: Languages spoken". Statistics New Zealand. March 2006. Retrieved 20 February 2008. ^ Didham, Robert; Potter, Deb (April 2005). Understanding and Working with Ethni city Data. Statistics New Zealand. ISBN 978-0-478-31505-9. Archived from the ori ginal on 25 November 2007. Retrieved 19 September 2010. ^ "Ethnic composition of the population". 2010 The Social Report. New Zealand Go vernment. Retrieved 29 July 2013. ^ "The New Zealand Land Cover Database". New Zealand Land Cover Database 2. New Zealand Ministry for the Environment. 1 July 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2011. ^ "Estimated resident population of New Zealand". Statistics New Zealand. 5 June 2013. Retrieved 5 June 2013. ^ "QuickStats About New Zealand's Population and Dwellings: Population counts". 2006 Census. Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 14 April 2011. ^ a b c d "New Zealand". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 20 April 2012. ^ "Equality and inequality: Gini index". Human Development Report 2009. United N ations Development Programme. Retrieved 14 April 2011. ^ "Human Development Report 2013". United Nations. p. 16. Retrieved 5 May 2013. ^ History of New Zealand. Newzealand.com. ^ King 2003, p. 41. ^ Hay, Maclagan & Gordon 2008, p. 72. Tasman's achieve ^ Wilson, John (March 2009). "European discovery of New Zealand ment". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 24 January 2011. ^ Wilson, John (September 2007). "Tasman s achievement". Te Ara the Encyclopedia o f New Zealand. Retrieved 16 February 2008. ^ Mackay, Duncan (1986). "The Search For The Southern Land". In Fraser, B. The N ew Zealand Book Of Events. Auckland: Reed Methuen. pp. 52 54.

^ a b Mein Smith 2005, p. 6. ^ Brunner, Thomas (1851). The Great Journey: an expedition to explore the interi or of the Middle Island, New Zealand, 1846-8. Royal Geographical Society. ^ McKinnon, Malcolm (November 2009). "Place names Naming the country and the mai n islands". Te Ara the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 24 January 2011. ^ "Confusion over NZ islands' names". BBC News. 22 April 2009. ^ May Eriksen, Alanah (25 April 2009). "Name quest unveils historic titles". The New Zealand Herald. ^ Davison, Isaac (22 April 2009). "North and South Islands officially nameless". The New Zealand Herald. ^ Wilmshurst, J. M.; Hunt, T. L.; Lipo, C. P.; Anderson, A. J. (2010). "High-pre cision radiocarbon dating shows recent and rapid initial human colonization of E ast Polynesia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108 (5): 1815. d oi:10.1073/pnas.1015876108. edit ^ McGlone, M.; Wilmshurst, J. M. (1999). "Dating initial Maori environmental imp act in New Zealand". Quaternary International 59: 5 0. doi:10.1016/S1040-6182(98)0 0067-6. edit ^ Murray-McIntosh, Rosalind P.; Scrimshaw, Brian J.; Hatfield, Peter J.; Penny, David (1998). "Testing migration patterns and estimating founding population siz e in Polynesia by using human mtDNA sequences". Proceedings of the National Acad emy of Sciences of the United States of America 95 (15): 9047 52. Bibcode:1998PNAS ...95.9047M. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.15.9047. ^ Wilmshurst, J. M.; Anderson, A. J.; Higham, T. F. G.; Worthy, T. H. (2008). "D ating the late prehistoric dispersal of Polynesians to New Zealand using the com mensal Pacific rat". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105 (22): 7 676. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.7676W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0801507105. edit ^ Moodley, Y.; Linz, B.; Yamaoka, Y.; Windsor, H. M.; Breurec, S.; Wu, J. -Y.; M aady, A.; Bernhoft, S.; Thiberge, J. -M. (2009). "The Peopling of the Pacific fr om a Bacterial Perspective". Science 323 (5913): 527 530. Bibcode:2009Sci...323..5 27M. doi:10.1126/science.1166083. PMC 2827536. PMID 19164753. edit ^ Clark, Ross (1994). "Moriori and Maori: The Linguistic Evidence". In Sutton, D ouglas. The Origins of the First New Zealanders. Auckland: Auckland University P ress. pp. 123 135. ^ Davis, Denise (September 2007). "The impact of new arrivals". Te Ara Encyclope dia of New Zealand. Retrieved 30 April 2010. ^ Davis, Denise; Solomon, Maui (March 2009). "'Moriori The impact of new arrival s'". Te Ara the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 23 March 2011. ^ a b Mein Smith 2005, p. 23. ^ Salmond, Anne. Two Worlds: First Meetings Between Maori and Europeans 1642 1772. Auckland: Penguin Books. p. 82. ISBN 0-670-83298-7. ^ King 2003, p. 122. ^ Fitzpatrick, John (2004). "Food, warfare and the impact of Atlantic capitalism in Aotearo/New Zealand". Australasian Political Studies Association Conference: APSA 2004 Conference Papers. ^ Brailsford, Barry (1972). Arrows of Plague. Wellington: Hick Smith and Sons. p . 35. ISBN 0-456-01060-2. ^ Wagstrom, Thor (2005). "Broken Tongues and Foreign Hearts". In Brock, Peggy. I ndigenous Peoples and Religious Change. Boston: Brill Academic Publishers. pp. 7 1 and 73. ISBN 978-90-04-13899-5. ^ Lange, Raeburn (1999). May the people live: a history of Maori health developm ent 1900 1920. Auckland University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-86940-214-3. ^ a b Rutherford, James (April 2009) [originally published in 1966]. "Busby, Jam es". In McLintock, Alexander. from An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Te Ara the E ncyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 7 January 2011. ^ McLintock, Alexander, ed. (April 2009) [originally published in 1966]. "Sir Ge orge Gipps". from An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Te Ara the Encyclopedia of Ne w Zealand. Retrieved 7 January 2011. ^ a b Wilson, John (March 2009). "Government and nation The origins of nationhoo d". Te Ara the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 7 January 2011. ^ McLintock, Alexander, ed. (April 2009) [originally published in 1966]. "Settle

ment from 1840 to 1852". from An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Te Ara the Encycl opedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 7 January 2011. ^ Foster, Bernard (April 2009) [originally published in 1966]. "Akaroa, French S ettlement At". In McLintock, Alexander. from An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Te Ara the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 7 January 2011. ^ Simpson, K (September 2010). "Hobson, William Biography". In McLintock, Alexan der. from the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Te Ara the Encyclopedia of Ne w Zealand. Retrieved 7 January 2011. ^ Phillips, Jock (April 2010). "British immigration and the New Zealand Company" . Te Ara the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 7 January 2011. ^ "Crown colony era the Governor-General". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Ma rch 2009. Retrieved 7 January 2011. ^ a b c Wilson, John (March 2009). "Government and nation The constitution". Te Ara the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 2 February 2011. ^ Temple, Philip (1980). Wellington Yesterday. John McIndoe. ISBN 0-86868-012-5. ^ "New Zealand's 19th-century wars overview". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. April 2009. Retrieved 7 January 2011. ^ Wilson., John (March 2009). "History Liberal to Labour". Te Ara the Encycloped ia of New Zealand. Retrieved 2 February 2011. ^ Boxall, Peter; Haynes, Peter (1997). "Strategy and Trade Union Effectiveness i n a Neo-liberal Environment" (PDF). British Journal of Industrial Relations 35 ( 4): 567 591. doi:10.1111/1467-8543.00069. ^ "War and Society". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 7 January 2011 . ^ Easton, Brian (April 2010). "Economic history Interwar years and the great dep ression". Te Ara the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 7 January 2011. ^ Derby, Mark (May 2010). "Strikes and labour disputes Wars, depression and firs t Labour government". Te Ara the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 1 Februa ry 2011. ^ Easton, Brian (November 2010). "Economic history Great boom, 1935 1966". Te Ara the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 1 February 2011. ^ Keane, Basil (November 2010). "Te Maori i te ohanga Maori in the economy Urban isation". Te Ara the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 7 January 2011. ^ Royal, Te Ahukaramu (March 2009). "Maori Urbanisation and renaissance". Te Ara the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 1 February 2011. ^ "Queen and New Zealand". The British Monarchy. Retrieved 28 April 2010. ^ a b c d "Factsheet New Zealand Political Forces". The Economist (The Economist Group). 15 February 2005. Archived from the original on 2006-05-14. Retrieved 4 August 2009. ^ "New Zealand Legislation: Royal Titles Act 1974". New Zealand Government. Febr uary 1974. Retrieved 8 January 2011. ^ "The Governor General of New Zealand". Official website of the Governor Genera l. Retrieved 8 January 2011. ^ "The Queen's role in New Zealand". The British Monarchy. Retrieved 28 April 20 10. ^ Harris, Bruce (2009). "Replacement of the Royal Prerogative in New Zealand". N ew Zealand Universities Law Review 23: 285 314. ^ a b "The Reserve Powers". Governor General. Retrieved 8 January 2011. ^ a b c d e "How Parliament works: What is Parliament?". New Zealand Parliament. 28 June 2010. Retrieved 8 January 2011. ^ "How Parliament works: People in Parliament". New Zealand Parliament. August 2 006. Retrieved 9 January 2011. ^ Wilson, John (November 2010). "Government and nation System of government". Te Ara the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 9 January 2011. ^ "Cabinet Manual: Cabinet". Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. 2008. Ret rieved 2 March 2011. ^ "The Judiciary". Ministry of Justice. Retrieved 9 January 2011. ^ "The Current Chief Justice". Courts of New Zealand. Retrieved 9 January 2011. ^ a b "First past the post the road to MMP". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. September 2009. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

^ "Reviewing electorate numbers and boundaries". Electoral Commission. 8 May 200 5. Retrieved 23 January 2012.[dead link] ^ "Sainte-Lagu allocation formula". Electoral Commission. 30 March 2005. Retrieve d 23 January 2012.[dead link] ^ Collins, Simon (May 2005). "Women run the country but it doesn't show in pay p ackets". The New Zealand Herald. ^ 2012 Failed States Index The Fund for Peace. Retrieved 31 July 2012 ^ Democracy Index 2011 Economist Intelligence Unit. Eiu.com. Retrieved 28 July 2 012. ^ Corruption Perceptions Index: Transparency International. Cpi.transparency.org (25 November 2011). Retrieved 28 April 2012. ^ New Zealand OECD Better Life Index. Oecdbetterlifeindex.org. Retrieved 28 July 2012. ^ McLintock, Alexander, ed. (April 2009) [originally published in 1966]. "Extern al Relations". from An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Te Ara the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 7 January 2011. ^ "Michael Joseph Savage". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. July 2010. Retriev ed 29 January 2011. ^ Patman, Robert (2005). "Globalisation, Sovereignty, and the Transformation of New Zealand Foreign Policy" (PDF). Working Paper 21/05. Centre for Strategic Stu dies, Victoria University of Wellington. p. 8. Retrieved 12 March 2007. ^ "Department Of External Affairs: Security Treaty between Australia, New Zealan d and the United States of America". Australian Government. September 1951. Retr ieved 11 January 2011. ^ "The Vietnam War". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. June 2008. Retrieved 11 January 2011. ^ "Sinking the Rainbow Warrior nuclear-free New Zealand". Ministry for Culture a nd Heritage. August 2008. Retrieved 11 January 2011. ^ "Nuclear-free legislation nuclear-free New Zealand". New Zealand History Onlin e. August 2008. Retrieved 11 January 2011. ^ Lange, David (1990). Nuclear Free: The New Zealand Way. New Zealand: Penguin B ooks. ISBN 0-14-014519-2. ^ "Australia in brief". Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Retr ieved 11 January 2011.[dead link] ^ a b c "New Zealand country brief". Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Re trieved 11 January 2011. ^ Bertram, Geoff (April 2010). "South Pacific economic relations Aid, remittance s and tourism". Te Ara the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 11 January 201 1. ^ Howes, Stephen (November 2010). "Making migration work: Lessons from New Zeala nd". Development Policy Centre. Retrieved 23 March 2011. ^ "Member States of the United Nations". United Nations. Retrieved 11 January 20 11. ^ "The Commonwealth in the Pacific". Commonwealth of Nations. Retrieved 11 Janua ry 2011.[dead link] ^ "Members and partners". Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development . Retrieved 11 January 2011. ^ "New Zealand Embassy Washington, United States of America: Defence relations". New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Retrieved 11 January 2011. ^ "Welcome to NZDF". New Zealand Defence Force. Retrieved 11 January 2011. ^ Ayson, Robert (2007). "New Zealand Defence and Security Policy,1990 2005". In Al ley, Roderic. New Zealand In World Affairs, Volume IV: 1990 2005. Wellington: Vict oria University Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-86473-548-5. ^ "The Battle for Crete". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. May 2010. Retrieved 9 January 2011. ^ "El Alamein The North African Campaign". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Ma y-2009. Retrieved 9 January 2011. ^ Holmes, Richard (September 2010). "World War Two: The Battle of Monte Cassino" . Retrieved 9 January 2011. ^ "Gallipoli stirred new sense of national identity says Clark". New Zealand Her