Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Cardiac Profiles of Liposomal Anthracyclines PDF

Uploaded by

alfox2000Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Cardiac Profiles of Liposomal Anthracyclines PDF

Uploaded by

alfox2000Copyright:

Available Formats

2052

Cardiac Proles of Liposomal Anthracyclines

Greater Cardiac Safety versus Conventional Doxorubicin?

Maria Theodoulou, Clifford Hudis, M.D.

M.D.

Breast Cancer Medicine Service, Memorial SloanKettering Cancer Center, New York, New York.

Although conventional doxorubicin is associated with favorable clinical outcomes in patients with a variety of tumor types, it long has been associated with the risk of development of cardiotoxicity. Therefore, researchers have focused their efforts on the development of new formulations to improve efcacy while minimizing associated toxicities. The most successful strategy reported to date has been liposomal encapsulation, which alters the pharmacokinetics of the drug, with the goal of maintaining efcacy and improving the therapeutic index. The cardiac proles of three liposomal anthracyclines, liposomal daunorubicin, nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin, and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, were reviewed. More studies will be needed to determine the cardiac safety of liposomal daunorubicin. Although nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin demonstrated more favorable cardiac safety compared with conventional doxorubicin, its cardiac safety appeared to be mitigated when high bolus doses were administered. Of the liposomal formulations, the strongest evidence of cardiac safety was observed with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin. Compared with conventional doxorubicin, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin was associated with a signicantly lower risk of development of cardiac events (P 0.001). Moreover, the risk of cardiotoxicity was not increased in patients who were treated with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin at cumulative doses 450 mg/m2 or in patients at increased risk for cardiotoxicity, such as those with prior adjuvant doxorubicin use. Liposomal doxorubicin formulations provided a favorable advantage over conventional doxorubicin in terms of cardiac safety. Recent evidence also suggests that the improved cardiac safety of liposomal doxorubicin formulations is reected by their successful use in combination with trastuzumab and other chemotherapy agents. Cancer 2004;100:2052 63. 2004 American Cancer Society.

KEYWORDS: doxorubicin, liposomes, anthracyclines, drug toxicity, breast neoplasms.

C

The authors are members of the Speakers Bureau for Genentech, Inc. Address for reprints: Maria Theodoulou, M.D., Breast Cancer Medicine Service, Memorial SloanKettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Avenue, New York, NY 10021; Fax: (212) 717-3619; E-mail: theodoum@mskcc.org Received September 19, 2003; revision received February 6, 2004; accepted February 17, 2004.

onventional doxorubicin is an established adjuvant therapy agent for many tumor types, and its use has been associated with favorable clinical outcomes. However, the clinical utility of this drug may be limited somewhat in patients with advanced disease by the risk of development of cardiotoxicity with cumulative doses 450 mg/m2. Consequently, researchers have focused their efforts on the development of new formulations and novel strategies to preserve and improve efcacy while minimizing cumulative toxicities.

Cardiotoxicity Associated with Conventional Doxorubicin

Cardiotoxicity associated with conventional doxorubicin may manifest as either an acute or chronic phenomenon.13 Patients treated with conventional doxorubicin who have acute cardiotoxicity present with rhythm disturbances, abnormal electrocardiographic changes,

2004 American Cancer Society DOI 10.1002/cncr.20207 Published online 20 April 2004 in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com).

Liposomal Anthracyclines/Theodoulou and Hudis

2053

and (rarely) acute but reversible reductions in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).13 These symptoms generally occur within 24 hours of infusion, are generally self-limiting, and do not appear to increase the future risk of cardiac events.2 Subacute or late cardiotoxicity manifests as a chronic complication of conventional doxorubicin treatment. The resultant congestive cardiomyopathy correlates with peak plasma doxorubicin concentrations as well as with the lifetime cumulative dose administered.4,5 According to the published literature, the incidence of conventional doxorubicin-induced congestive heart failure (CHF) is approximately 3% at a cumulative dose of 400 mg/m2, increasing to 7% at 550 mg/m2 and to 18% at 700 mg/m2.6 Wigler et al. also recently demonstrated a correlation between increasing conventional doxorubicin doses and cardiotoxicity in patients with metastatic breast carcinoma: At cumulative doses of 500 550 mg/m2, the incidence of cardiac events was 13%, increasing to 17% at doses of 550 600 mg/m2 and to 33% at doses 600 mg/m2.7 Consistent with these ndings, the prescribing information for conventional doxorubicin provides estimates of the probability of developing cardiac toxicity in patients who receive conventional doxorubicin: 12% at a total cumulative dose of 300 mg/m2 and 6 20% at cumulative doses of 500 mg/m2.8 Thus, the recommended lifetime cumulative dose for conventional doxorubicin is limited to 450 550 mg/m2.5,9 However, a recent analysis of 3 Phase III trials (n 630 patients) suggested that conventional doxorubicin-induced CHF may occur at lower cumulative doses ( 300 mg/m2) and with somewhat greater frequency than previously observed.10 In that analysis, the estimated cumulative percentage of patients developing doxorubicin-related CHF was 5% at a cumulative dose of 400 mg/m2, increasing to 26% at 550 mg/m2 and to 48% at 700 mg/m2. These new data may have important implications for the currently accepted lifetime cumulative dose for conventional doxorubicin. Because cardiotoxicity associated with conventional doxorubicin often is irreversible, and clinical signs and symptoms may persist for months or longer after treatment, there has been an interest in identifying those groups of patients at increased risk for the development of cardiac events.5,11 To date, several patient characteristics have been identied that confer a greater risk for cardiotoxicity. These include the extent of prior conventional doxorubicin exposure (patients who have received higher cumulative doses are more likely to experience cardiac problems); age (both elderly patients age 65 years and very young patients age 4 years are at greater risk); a history of cardiac disease; and previous cancer therapies, such

as mediastinal radiation therapy, high-dose doxorubicin infusion, and the concurrent use of chemotherapy regimens that include paclitaxel or trastuzumab.1,4,12

Efforts to Decrease Conventional Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity

One strategy to protect against myocardial damage involves the development of anthracycline analogs, such as epirubicin. Although the risk of developing cardiotoxicity occurs at a higher cumulative dose (900 mg/m2 compared with 400 450 mg/m2 using conventional doxorubicin),1,13 a decrease of 10% in LVEF has been observed at cumulative epirubicin doses 450 mg/m2.1 Another strategy has involved the use of low-dose, prolonged, continuous infusion of conventional doxorubicin, which also reportedly reduced the incidence of cardiotoxicity compared with standard dosing controls (i.e., short infusion over 1520 minutes).14 However, the disadvantages of prolonged infusion may include hospitalization and the use of a portable infusion pump,15 both of which increase cost and may have a negative impact on patient quality of life. The coadministration of dexrazoxane with conventional doxorubicin prevents free radical formation and improves cardiac safety.1,15,16 This improved cardiac safety was reected in a study of 150 patients with advanced breast carcinoma who were treated with conventional doxorubicin at a dose of 50 mg/m2 every 3 weeks with or without dexrazoxane at a dose of 1000 mg/m2.17 Patients who received dexrazoxane tolerated signicantly larger doses of conventional doxorubicin for signicantly longer periods. The full cardiac toxicity analysis (clinical, LVEF by multigated acquisition [MUGA] scans, and endomyocardial biopsy) also signicantly favored the dexrazoxane group (P 0.001). Although they were not statistically signicant, response rates were lower in patients who received dexrazoxane (37%) compared with patients who did not receive dexrazoxane (41%), suggesting that dexrazoxane may interfere with the antitumor efcacy of conventional doxorubicin; however, this theory has not been proven in prospective clinical trials.15,16,18,19 Because this issue remains unresolved, there is a great need to explore safer options.

Liposomal Anthracyclines

A successful strategy for reducing the cardiotoxicity associated with conventional doxorubicin involves liposomal encapsulation, which alters the tissue distribution and pharmacokinetics of these agents with the objective of maintaining efcacy and improving the therapeutic index.5,20 The cardiac safety proles of three liposomal anthracycline formulations, including liposomal daunorubicin, nonpegylated liposomal

2054

CANCER May 15, 2004 / Volume 100 / Number 10

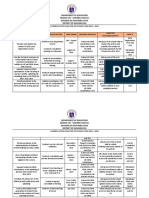

TABLE 1 Comparison of Liposomal Anthracycline Formulationsa

Liposome diameter (nm) 45 180 100 Half-life (hrs) 4.4 2.03.0 55.0b Avoids phagocytosis No No Yesb Specic tumor targeting No No Yesb

Formulation Liposomal daunorubicin Nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin

a

breast carcinoma;25,26 however, nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin also currently is under investigation for the treatment of other tumor types, including nonHodgkin-related and acquired immunodeciency syndrome (AIDS)-related lymphomas and Kaposi sarcoma.27,28 Additional studies currently are being conducted to determine the role of nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin in combination with the monoclonal antibody trastuzumab in the treatment of patients with advanced or metastatic breast carcinoma.29

See Gilead Sciences, Inc.,22 Elan Pharmaceuticals,23 and Ortho Biotech Products.24 Pegylation extends half-life and allows pegylated liposomal doxorubicin to avoid phagocytosis and target the tumor.

b

Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin

Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin represents a unique formulation in which a polyethylene glycol layer surrounds the doxorubicin-containing liposome as a result of a process termed pegylation. Pegylation protects the liposomes from detection by the mononuclear phagocyte system and increases the plasma half-life compared with conventional doxorubicin.20,30 The size of these drug-containing vesicles allows the liposomes to extravasate through leaky tumor vasculature. This property, combined with its longer halflife, promotes targeted drug delivery to the tumor site.20 Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin is indicated for the treatment of metastatic ovarian carcinoma in patients with disease that is refractory to both paclitaxel-based and platinum-based chemotherapy regimens and for the treatment of AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma in patients with disease that has progressed during prior combination therapy or in patients who are intolerant to such therapy.24 Currently, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin is being investigated in a variety of other disease types, including breast carcinoma, multiple myeloma, endometrial malignancies, and Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin was approved recently in the European Union and in Canada as monotherapy for metastatic breast carcinoma in patients who are at increased cardiac risk, and it holds a compendium listing in the U.S. for patients with metastatic breast carcinoma. Of the three liposomal anthracycline formulations, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin differs most signicantly from conventional doxorubicin in terms of its pharmacokinetics and toxicity prole.31 Unlike conventional doxorubicin, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin is associated with low concentrations of free doxorubicin, with limited distribution to the myocardium.20,32 These characteristics suggest that pegylated liposomal doxorubicin may be less cardiotoxic than conventional doxorubicin, a hypothesis that was supported rst by results from preclinical animal studies and has been conrmed by an increasing body of clinical data.7,20,3336

doxorubicin, and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, were reviewed. This article is focused mainly on pegylated liposomal doxorubicin because it is the most widely studied of the liposomal anthracyclines. Liposomal anthracyclines were designed with the intent to reduce the risk of cardiotoxicity associated with conventional doxorubicin while preserving antitumor efcacy. The rationale supporting this design is that liposomes cannot escape the vascular space in areas that have tight capillary junctions, such as the heart muscle, but can exit the circulation in tissues and organs lined with cells that are not tightly joined (i.e., areas of tumor growth).21 Therefore, liposomal anthracyclines should direct drug preferentially away from sites of potential toxicity but should leave the tumor tissue exposed. The individual characteristics of each of the available liposomal formulations (i.e., halflife, tumor specicity, and liposome size) are shown in Table 1.2224

Liposomal daunorubicin

Liposomal daunorubicin has been approved since 1996 as rst-line cytotoxic therapy for patients with advanced human immunodeciency virus-associated Kaposi sarcoma; however, it is not recommended for use in patients with less than advanced disease.22 The clinical utility of liposomal daunorubicin in the treatment of other types of malignancies, including breast carcinoma, leukemias, and lymphomas, needs to be determined.

Nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin

Although nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin has been approved in Europe in combination with cyclophosphamide as rst-line treatment for patients with metastatic breast carcinoma,23 it remains under clinical investigation in the U.S. The majority of clinical trials have been conducted in patients with metastatic

Liposomal Anthracyclines/Theodoulou and Hudis TABLE 2 Cardiac Safety of Liposomal Daunorubicin

Study OByrne et al.41 Fassas et al.42 No. of patients 16 28 Treatment LD at a dose of 80 mg/m2, escalated to 100, 120, 150, and 180 mg/m2 LD at a dose of 75 mg/m2, escalated to 100, 125, and 150 mg/m2 (up to a cumulative dose of 375 mg/m2) for 3 days Not published; MTD was 155 mg/m2 in patients receiving conventional therapy; 100 mg/m2 in those with prior radiation RR PR, 7%; SD, 40% 46% Median OS 13.75 mos 208 days Cardiac safety

2055

Lowis et al.45

48a

Unknown

Unknown

Signicant decreases in LVEF noted in 3 patients (19%) LVEF decreased to 45% (n 1); cardiotoxicity and death at cumulative doses of 750900 mg/m2 (n 2) Cardiotoxicity occurred in 14 patients (29%); 2 of those patients died as a result of cardiac events

RR: response rate; OS: overall survival; LD: liposomal daunorubicin; PR: partial response; SD: stable disease; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; MTD: maximum tolerated dose. a Pediatric population.

Cardiac Safety Prole of Liposomal Daunorubicin

Results from early preclinical and early clinical studies have suggested that liposomal daunorubicin may have a more favorable cardiac safety prole compared with the conventional formulation.37 40 However, evidence of cardiotoxicity has been observed at higher cumulative doses of liposomal daunorubicin (600 900 mg/ m2) (Table 2).41,42

onstrated evidence of cardiac toxicity at cumulative doses of liposomal daunorubicin (600 960 mg/m2) similar to those expected to lead to cardiac events with the conventional daunorubicin formulation (650 mg/m2).

Acute myeloid leukemia

Fassas et al. conducted a Phase III dose-escalation study of single-agent liposomal daunorubicin in 28 patients with recurrent or refractory acute myeloid leukemia and a history of conventional anthracycline treatment.42 Cohorts of 6 patients were treated at each of the following dose levels for 3 consecutive days: 75 mg/m2, 100 mg/m2, 125 mg/m2, or 150 mg/m2 of liposomal daunorubicin. There was no evidence of cardiotoxicity at doses of 75 mg/m2, 100 mg/m2, or 125 mg/m2, up to a cumulative dose of 375 mg/m2. However, 2 patients developed cardiotoxicity at the 150-mg/m2 dose level and died (cumulative dose, 750 900 mg/m2), although a relation to treatment was not reported. Of the 14 patients who completed 6 months of follow-up, the LVEF dropped below 45% in 1 patient, with no related clinical signs or symptoms noted. The highest acceptable cumulative dose of liposomal daunorubicin in this study was 750 mg/m2.

Metastatic breast carcinoma

OByrne et al. conducted a Phase I dose-escalation study to determine the maximum tolerated dose, safety prole, and activity of liposomal daunorubicin in patients with metastatic breast carcinoma.41 Sixteen anthracycline-na ve patients received a 2-hour infusion of liposomal daunorubicin at an initial dose of 80 mg/m2 every 21 days, which was increased to 100 mg/m2, 120 mg/m2, 150 mg/m2, and 180 mg/m2 thereafter. All patients had normal cardiac function at baseline, dened as LVEF 50%. In this study, the maximum tolerated dose was 120 mg/m2, with doselimiting toxicities of prolonged Grade 4 neutropenia or neutropenic pyrexia. Three patients had cardiotoxicity, as evidenced by a substantial but asymptomatic decrease in LVEF from baseline. Specically, Grade 1 cardiotoxicity (reduction in LVEF from 65% to 50%) was seen in 1 patient who had received a cumulative liposomal daunorubicin dose of 800 mg/m2. Another patient experienced Grade 2 cardiotoxicity (reduction in LVEF from 75% to 46%) at a cumulative liposomal daunorubicin dose of 600 mg/m2; this patient also had received a prior conventional doxorubicin dose totaling 300 mg/m2. The third patient experienced a decrease in LVEF from 84% to 57% after receiving a cumulative liposomal daunorubicin dose of 960 mg/ m2. It is interesting to note that these patients dem-

Pediatric solid tumors

Previous studies suggest that children may be more susceptible to the cardiac effects of anthracyclines compared with adults.6,43,44 Liposomal daunorubicin has been evaluated for use in the pediatric population. Lowis et al. conducted a Phase I study to determine the dose-limiting toxicity and maximum tolerated dose of liposomal daunorubicin in 48 children (ages 118 years) with recurrent or resistant solid tumors.45 Because neutropenia was expected to be the dose-

2056

CANCER May 15, 2004 / Volume 100 / Number 10

TABLE 3 Cardiac Safety of Nonpegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin

Study Harris et al.25 No. of patients 108 116 Treatment D-99 at a dose of 75 mg/m2 every 3 weeks or conventional doxorubicin, 75 mg/m2 every 3 weeks D-99 at a dose of 60 mg/m2 CP at a dose of 600 mg/m2 or conventional doxorubicin, 60 mg/m2 CP, 600 mg/m2 D-99 at a dose of 135 mg/m2 G-CSF, 5 g/kg, every 21 days RR 26% 26% Median OS 16.0 mos 20.0 mos Cardiac safety Cardiac events: 13% for D-99 vs. 29% for conventional doxorubicin (P 0.0001); CHF: 2% for D-99 vs. 8% for conventional doxorubicin (P 0.0001) Cardiac events: 6% for D-99/CP vs. 21% for conventional doxorubicin/CP (P 0.0002); CHF: 0 patients with D-99/CP vs. 5 patients with conventional doxorubicin/CP (P 0.02) Cardiac events and CHF in 38% and 13% of patients, respectively; 1 death due to cardiomyopathy at a cumulative dose of 1035 mg/m2

Batist et al.26

142 155

43% 43%

19.0 mos 16.0 mos

Shapiro et al.47

52

46%

22.1 mos

RR: response rate; OS: overall survival; D-99: nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin; CP: cyclophosphamide; CHF: congestive heart failure; G-CSF: granulocyte colony-stimulating factor.

limiting toxicity, a second phase of the study was planned with the use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. However, the second phase of the study was never completed because of substantial cumulative cardiac toxicity. Two children died of acute cardiac toxicity after four cycles of liposomal daunorubicin (at unpublished doses); both children previously had received conventional anthracyclines and one child had a history of spinal and pulmonary radiation therapy. Twelve additional patients demonstrated evidence of cardiac toxicity, with reductions in fractional shortening and/or ejection fraction (specic data not provided). It is worth noting that 2 of those 12 patients were anthracycline-na ve. Consequently, the investigators concluded that the cardiotoxic effects of liposomal daunorubicin would limit its clinical utility in this population.

Cardiac Safety Prole of Nonpegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin

Several clinical trials have examined the cardiotoxicity associated with nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin. Results from those studies indicate less cardiotoxicity compared with conventional doxorubicin, although cardiac safety appears to be mitigated at higher bolus doses (Table 3).

Metastatic breast carcinoma

In a Phase III study conducted by Harris et al., 224 patients with metastatic breast carcinoma received either nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin at a dose of 75 mg/m2 or conventional doxorubicin at a dose of 75 mg/m2 every 3 weeks.25 Patients were stratied by prior adjuvant therapy with conventional doxorubicin, with a maximum cumulative lifetime conventional doxorubicin dose of 300 mg/m2. Although the overall response rate was the same (26%) for both the liposomal and conventional doxorubicin treatment groups, signicantly fewer cardiac adverse events were noted to occur with nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin (13% vs. 29% with the conventional formulation; P 0.0001). Moreover, the median cumulative doxorubicin dose at the onset of cardiotoxicity was signicantly higher with nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin (785 mg/m2 compared with 570 mg/m2 for conventional doxorubicin; P 0.0001). Consistent with these ndings, clinical CHF was observed in signicantly fewer nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicintreated patients (2% vs. 8% of patients who received conventional doxorubicin; P 0.0001), and endomyocardial biopsy results revealed signicantly fewer non-

Conclusions

Based on the available published literature, current recommendations suggest that cumulative doses of liposomal daunorubicin should not exceed 650 mg/m2 in adults.46 However, the lack of published studies directly comparing the cardiac safety of liposomal daunorubicin with that of conventional daunorubicin makes it difcult to draw meaningful conclusions regarding the relative safety of either agent. Therefore, comparative studies are needed to determine the maximum tolerated cumulative dose of liposomal daunorubicin and to dene further its cardiac safety and place in the chemotherapeutic armamentarium.

Liposomal Anthracyclines/Theodoulou and Hudis

2057

pegylated liposomal doxorubicin-treated patients with a Billingham score 2.5 (26% vs. 71% of patients who received conventional doxorubicin; P 0.02). The cardiac safety of nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin as part of a combined chemotherapy regimen also has been evaluated. In a Phase III study, Batist et al. compared the efcacy and safety of nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide with that of conventional doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide as rst-line treatment for metastatic breast carcinoma.26 In all, 297 patients who had received cumulative lifetime conventional doxorubicin doses of 300 mg/m2 were treated with either nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin at a dose of 60 mg/m2 or conventional doxorubicin at a dose of 60 mg/m2 plus cyclophosphamide at a dose of 600 mg/m2 every 3 weeks. Patients were stratied based on prior conventional doxorubicin exposure; 10% of patients in each treatment group had received prior conventional doxorubicin therapy, with a median cumulative dose of 240 mg/m2. Cardiotoxicity (dened as a decrease 20% in LVEF from baseline to a nal value of 50%, a decrease 10% in LVEF from baseline to a nal value 50%, or clinical evidence of CHF) was observed in 6% of patients who were treated with nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin, compared with 21% of patients who received conventional doxorubicin (P 0.0001). The onset of cardiotoxicity occurred at much higher median cumulative doses with nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin (estimated at 2200 mg/ m2) than with conventional doxorubicin (480 mg/m2), corresponding to an 80% lower risk of cardiotoxicity associated with nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin. Although none of the patients in the nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin group developed clinical CHF, 5 patients who received conventional doxorubicin developed CHF (P 0.02). All the CHF cases occurred at lifetime cumulative doxorubicin doses ranging from 360 mg/m2 to 480 mg/m2, and 4 of the 5 patients involved were anthracycline-na ve prior to study enrollment.26 The improved safety prole of nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin led Shapiro et al. to investigate its use in high doses (135 mg/m2) with lgrastim (5 g/ kg) as rst-line treatment for patients with metastatic breast carcinoma.47 The dose escalation of nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin did not improve efcacy and resulted in considerably greater cardiac toxicity. In all, 52 patients (23% of whom had received prior adjuvant therapy with conventional doxorubicin) were enrolled and received a median cumulative nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin dose of 405 mg/m2 (range, 1351065 mg/m2). Cardiac adverse events oc-

curred in 38% of patients, including 13% who developed CHF. Another 8% of patients experienced reductions 20% in LVEF, whereas an additional 17% of patients had LVEF decreases 10%. One patient died of cardiomyopathy after receiving a total cumulative nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin dose of 1035 mg/m2.

Conclusions

The results of these studies suggest that nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin exhibits greater cardiac safety compared with conventional doxorubicin, even in patients who have a history of conventional adjuvant anthracycline treatment. However, cardiac toxicity may be increased when higher doses (i.e., 135 mg/m2) of nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin are administered.

Cardiac Safety Prole of Pegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin Kaposi sarcoma

The rst clinical evidence supporting the improved cardiac safety of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin was provided by Berry et al. (Table 4).33 Their retrospective study compared endomyocardial biopsy results from patients with Kaposi sarcoma who received pegylated liposomal doxorubicin with those of a historic control group that was treated with conventional doxorubicin. A total of 10 anthracycline-na ve patients received cumulative doses of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin 400 mg/m2 (given in doses of 20 mg/m2 every 23 weeks) and underwent endomyocardial biopsy. Control patients were selected from a group of 131 patients who had undergone endomyocardial biopsies between 1975 and 1983 as part of 2 Northern California Oncology Group studies. Those patients had received conventional doxorubicin at doses of 60 mg/m2 every 3 weeks or 20 mg/m2 once weekly, with endomyocardial biopsies performed at predetermined cumulative dose levels. For purposes of comparison, control patients were stratied into two groups. Control Group 1 was selected on the basis of peak and cumulative conventional doxorubicin doses and Control Group 2 was selected on the basis of peak dose alone. All biopsy results were graded using the Morphologic Grading System for Cardiotoxicity developed by Billingham and Bristow.48 Although the mean and median cumulative doses of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin were higher compared with the doses in both control groups, none of the cardiac biopsy results from patients who were treated with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin demonstrated signs of myocarditis, opportunistic infection, cardiomyopathy, or involvement of Kaposi sarcoma or

2058

CANCER May 15, 2004 / Volume 100 / Number 10

TABLE 4 Cardiac Safety of Pegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin

Study Berry et al.33 No. of patients 10 Treatment PLD at a dose of 20 mg/m2 every 23 weeks; cumulative doses 400 mg/m2 RR NR Median OS NR Cardiac safety Signicantly lower median biopsy scores with PLD vs. matched control groups receiving conventional doxorubicin (P 0.002 vs. matched peak and cumulative dose; P 0.001 vs. matched peak dose alone) Median biopsy score, 0.75

Gabizon and Lyass35

Safra et al.34

42

Median cumulative PLD dose, 707.5 mg/m2; median total anthracycline exposure, 908.5 mg/m2 Cumulative PLD doses of 5001500 mg/m2

NR

NR

NR

NR

Wigler et al.7

254 255

PLD at a dose of 50 mg/m2 every 4 weeks or conventional doxorubicin, 60 mg/m2, every 3 weeks

27% 30%

20.1 mos 22.0 mos

Median change in LVEF of 2% and not considered clinically signicant; endomyocardial biopsy scores, 01.5 and no cardiac symptoms Signicantly lower risk of developing a cardiac event with PLD vs. conventional doxorubicin (P 0.001); no patients with signs or symptoms of CHF with PLD vs. 10 with conventional doxorubicin

RR: response rate; OS: overall survival; PLD: pegylated liposomal doxorubicin; NR: not reported; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; CHF: congestive heart failure.

other malignancies. In addition, the median biopsy scores were signicantly lower in patients who were treated with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin: 0.3 (range, 0.0 1.5) compared with 3.0 (range, 1.53.0) (P 0.002) for conventional doxorubicin Control Group 1 and 1.25 (range, 0.0 3.0) (P 0.001) for Control Group 2.33 The cumulative doxorubicin dose is the most important factor in the development of cardiac toxicity, as discussed earlier. Thus, it is interesting to note that, despite receiving higher median cumulative doses, patients who were treated with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin had signicantly lower endomyocardial biopsy scores compared with Control Group 1 (who were selected on the basis of cumulative conventional doxorubicin dose). In addition, the second most important factor relating to doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity is the size of the bolus administered; the closest comparison was between pegylated liposomal doxorubicin at a dose of 20 mg/m2 biweekly and conventional doxorubicin at a dose of 20 mg/m2 weekly (i.e., Control Group 2). Again, patients who were treated with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin were found to have signicantly lower endomyocardial biopsy scores compared with Control Group 2, although they received higher cumulative doses.33 Likewise, data from a series of patients with AIDSrelated Kaposi sarcoma suggest that some patients may tolerate cumulative pegylated liposomal doxorubicin

doses of up to 2360 mg/m2 (given over a 5-year period) with little or no decrease in cardiac function, although these ndings require conrmation in controlled clinical trials.36

Advanced malignancies

In a prospective study, endomyocardial biopsies were performed to assess the cardiac effects of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin histologically in patients with advanced malignancies who received doxorubicinequivalent doses 550 mg/m2 (including pegylated liposomal doxorubicin) or 400 mg/m2 of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin alone.35 Eight patients were enrolled, and 10 biopsy samples were obtained (2 patients underwent 2 biopsies each). All patients had received prior chemotherapy (four patients had received prior conventional doxorubicin), and six patients had received prior radiation therapy. The median cumulative prior conventional doxorubicin and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin doses were 270.0 mg/m2 and 707.5 mg/m2, respectively, and the median total anthracycline exposure was 908.5 mg/m2. The median biopsy score (Billingham scale) was 0.75 (range, 0.0 1.5). These results suggest minimal cardiotoxicity with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin administration, even at doses exceeding the recommended maximum lifetime cumulative doxorubicin dose of 450 550 mg/m2.

Liposomal Anthracyclines/Theodoulou and Hudis

2059

Solid tumors

Two larger trials have conrmed the improved cardiac safety of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin. In the rst of those studies, Safra et al. conducted a retrospective review of patients with solid tumors who had received pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in eight Phase I and II studies.34 Of 237 patients who were included in those studies, 42 patients had received cumulative doses of pegylated doxorubicin ranging from 500 mg/m2 to 1500 mg/m2 (median dose, 660 mg/m2). Seven of those patients also had received conventional doxorubicin prior to study entry. All patients underwent serial determinations of LVEF, as measured by MUGA scans. At baseline, the median LVEF was 63% (range, 50 79%), and nal MUGA scans revealed a median LVEF of 61% (range, 49 78%). Thus, the median change in LVEF was 2% (range, from 15% to 9%). Although this change was statistically signicant (P 0.009), the majority of changes were 10% in magnitude and were not considered clinically signicant. The median change in LVEF was only 1% in patients who had not received conventional doxorubicin prior to study enrollment (n 34 patients), whereas patients who had a history of conventional doxorubicin treatment (n 7 patients) experienced a median change in LVEF of 7%. In all, 5 patients experienced LVEF decreases 10%; however, no patient developed CHF symptoms after 6 months of follow-up. Moreover, all 5 patients had nal LVEF measurements 52%. Six patients also underwent endomyocardial biopsy in this analysis. Biopsy scores for those patients ranged from 0.0 to 1.5 at cumulative pegylated liposomal doxorubicin doses of 490 1320 mg/m2 with no evidence of cardiac symptoms.34

Metastatic breast carcinoma

The second large-scale study to our knowledge was a prospective Phase III trial comparing pegylated liposomal doxorubicin with conventional doxorubicin in 509 patients with metastatic breast carcinoma and no prior evidence of cardiac disease.7 Cardiac safety was a primary endpoint in that study. Patients were assigned randomly to receive a 1-hour infusion of either pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (50 mg/m2 every 4 weeks; n 254 patients) or conventional doxorubicin (60 mg/m2 every 3 weeks; n 255 patients). MUGA scans were used to assess LVEF at baseline, after 300 mg/m2 cumulative doxorubicin exposure, and after every additional 100 mg/m2 (pegylated liposomal doxorubicin) or 120 mg/m2 (conventional doxorubicin). Patients also were monitored for the development of signs and symptoms of CHF. Cardiotoxicity

was dened as a decrease from baseline of 20% in LVEF if the resting LVEF remained within the normal range or a decrease of 10% if the LVEF was below the institutional lower limit of normal. With respect to cardiac risk factors, both treatment groups were well matched at baseline; approximately 48% of patients who received pegylated liposomal doxorubicin and 47.4% of patients who received conventional doxorubicin had at least 1 cardiac risk factor present. The results of the study demonstrated that pegylated liposomal doxorubicin has similar efcacy and improved cardiac safety compared to that of conventional doxorubicin. The median progression-free survival was similar with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin and conventional doxorubicin (6.9 months vs. 7.8 months, respectively; P 0.99). Likewise, the overall survival was 20.1 months for patients who received pegylated liposomal doxorubicin compared with 22.0 months for patients who received conventional doxorubicin (P 0.94). The use of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin translated into a nearly 5-fold reduction in the incidence of cardiac events: Cardiotoxicity was observed in 10 patients who were treated with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin versus 48 patients who were treated with conventional doxorubicin. In addition, none of the patients who received pegylated liposomal doxorubicin developed signs and symptoms of CHF, compared with 10 patients who received conventional doxorubicin. Moreover, cumulative pegylated liposomal doxorubicin doses in excess of 450 mg/m2 were not associated with a signicant decrease from baseline LVEF.7 The risk of developing a cardiac event was significantly lower for patients who were treated with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin compared with patients who received conventional doxorubicin (P 0.001). Patients who were treated with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin at cumulative doses from 500 mg/m2 to 550 mg/m2 had an 11% risk of developing a cardiac event, whereas the risk was 40% in patients who received the same dose of conventional doxorubicin. This reduction in risk also was apparent in patients who were at increased risk for cardiotoxicity, particularly in those who had received prior conventional doxorubicin as adjuvant therapy (Table 5).7

Conclusions

The results of these studies demonstrate that pegylated liposomal doxorubicin has activity similar to that of conventional doxorubicin but is associated with a signicantly reduced risk of cardiac toxicity. Cumulative doses of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin 500 mg/m2 are associated with a lower risk of cardiotoxicity compared with conventional doxorubicin. Thus, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin may be of particular

2060

CANCER May 15, 2004 / Volume 100 / Number 10 TABLE 5 Incidence of Cardiotoxicity with Pegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin in High-Risk Patientsa

Risk factor Noncardiac risk factors Adjuvant anthracycline exposure Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin Conventional doxorubicin Age 55 yrs Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin Conventional doxorubicin Cardiac risk factors Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin Conventional doxorubicin

HR: hazard ratio; 95% CI: 95% condence interval. a See Wigler et al.7

No. of patients

No. with cardiotoxicity

HR (95% CI)

38 40 159 152 122 121

1 11 6 18 5 21

7.27 (0.9356.80) 2.04 (0.815.18) 2.7 (1.017.18)

benet in patients who are at increased risk for doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity (i.e., those with a history of cardiac disease or previous conventional doxorubicin exposure, the elderly, or young patients who are expected to live long after treatment has been completed). Ongoing studies are being conducted to evaluate the use of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in combination with other agents in a variety of hematologic and solid tumors.

Future Directions for Liposomal Anthracyclines

Because of their improved cardiac safety proles, there is interest in using liposomal anthracyclines in combination with other agents. One such agent is trastuzumab, a recombinant monoclonal antibody directed against the human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER-2), the product of a gene that is overexpressed in 2530% of patients with breast carcinoma and is associated with a particularly aggressive disease course.12 Trastuzumab has shown some antitumor activity when used as single-agent therapy for rst-line treatment49 as well as in the salvage setting in heavily pretreated patients.50,51 However, it appears to have greater potential when used in combination with established chemotherapy regimens in women with HER-2-positive metastatic disease.12 The efcacy and safety of trastuzumab as part of a rst-line chemotherapy regimen for women with metastatic breast carcinoma have been evaluated in a large Phase III study.12 In that study, patients who had not received prior adjuvant therapy with conventional anthracycline (n 281 patients) were treated with conventional doxorubicin at a dose of 60 mg/m2 (or epirubicin at a dose of 75 mg/m2) plus cyclophosphamide at a dose of 600 mg/m2, with or without the addition of trastuzumab (4 mg/kg loading dose followed by 2 mg/kg weekly), whereas patients who had a history of conven-

tional anthracycline treatment (n 188 patients) received paclitaxel at a dose of 175 mg/m2 alone or in combination with trastuzumab. Treatment was administered every 3 weeks for 6 cycles. Although the addition of trastuzumab increased efcacy, including a signicantly longer time to disease progression (P 0.001) and signicantly improved overall survival (P 0.046), substantial cardiac toxicity was observed. Thirty-nine of 143 patients (27%) who received conventional doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and trastuzumab developed cardiotoxicity compared with 11 of 135 patients (8%) who received conventional doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide alone. Moreover, the addition of trastuzumab increased the incidence of cardiac dysfunction in patients who received paclitaxel-containing regimens: Twelve of 91 patients (13%) treated with paclitaxel plus trastuzumab had evidence of cardiac toxicity compared with only 1 of 95 patients (1%) in the group that received paclitaxel alone.12 Currently, trastuzumab is indicated for the treatment of patients with metastatic breast carcinoma who have tumors that overexpress the HER-2 protein and who have received one or more chemotherapy regimens for their metastatic disease or in combination with paclitaxel for those patients who have not yet received chemotherapy for their metastatic disease. However, based on its cardiotoxicity prole, trastuzumab should be used with caution, especially when combined with conventional doxorubicin or paclitaxel. We previously combined nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin with trastuzumab as rst-line, secondline, or third-line therapy in an effort to maintain an acceptable level of cardiac safety in patients with advanced breast carcinoma.29 Thirty-nine patients received nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin at a dose of 60 mg/m2 every 3 weeks plus trastuzumab at an

Liposomal Anthracyclines/Theodoulou and Hudis

2061

initial dose of 4 mg/kg (Week 1) followed by weekly doses of 2 mg/kg. Cardiac safety was assessed on the basis of LVEF, as measured by MUGA scans at baseline and every two cycles. Cardiac toxicity was dened as the development of signs and symptoms of CHF, a decline in LVEF 20% if it was still within the normal range, or a decline in LVEF 10% if it was below the lower limit of normal. Preliminary results from that study suggest that cardiac toxicity is minimal when nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin is combined with trastuzumab.29 Of the 29 patients who received 4 cycles of treatment and were evaluable for cardiac safety, 2 patients experienced cardiac events: 1 patient with an asymptomatic decrease in LVEF and 1 patient with clinical CHF. It is interesting to note that both patients had received prior conventional doxorubicin treatment, and their cardiac function improved after discontinuation of therapy. Thus, the combination of nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin and trastuzumab appears to have an acceptable cardiac safety prole. Larger trials currently are being designed to examine the safety and efcacy of this combination further. The results of a Phase II trial evaluating the combination of nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin, paclitaxel, and trastuzumab were presented recently at the 26th annual San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.52 Fifty-four patients with locally advanced breast carcinoma (n 30 patients) or metastatic breast carcinoma (n 24 patients) were treated with nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin at a dose of 50 mg/m2 every 3 weeks and paclitaxel at a dose of 80 mg/m2 with trastuzumab at a dose of 2 mg/kg (4 mg/kg loading dose) weekly for 52 weeks. An overall response rate of 92.3% was observed. The most common Grade 3/4 toxicity was neutropenia. Although an asymptomatic decrease in LVEF 50% was reported in several patients, only 3 patients discontinued therapy for this reason. Moreover, there were no patients with symptomatic heart failure reported during the study. Increasing evidence suggests that pegylated liposomal doxorubicin may be administered safely with trastuzumab. Early results of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study 3198, which examined the cardiac safety and efcacy of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin and docetaxel trastuzumab in patients with metastatic breast carcinoma, were presented by Wolff et al. at the recent 2003 Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.53 The treatment regimen was comprised of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin at a dose of 30 mg/m2 and docetaxel at a dose of 60 mg/m2 every 3 weeks without trastuzumab in HER-2 nonoverexpressing patients or in combination with trastuzumab, given at a dose of 4 mg/kg initially and 2

mg/kg weekly thereafter, in HER-2-positive patients. Preliminary evaluation of cardiac function at baseline and after 4 cycles of therapy in 22 patients who received pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, docetaxel, and trastuzumab showed no signicant effect on LVEF ( 4%) and no clinical episodes of CHF.

MUGA Scan Recommendations

All patients who are being considered for treatment with liposomal anthracyclines should have a MUGA scan performed at baseline; to reduce the risk of developing cardiotoxicity, liposomal anthracycline therapy should be used cautiously in patients with an LVEF 50% at baseline. Repeat MUGA scans should be performed after the cumulative dose reaches 400 mg/m2 and again at every 100 120 mg/m2 cumulative dose increase thereafter. Patients with a history of anthracycline treatment should have MUGA scans performed more frequently (e.g., after every 200 mg/ m2-dose increment). If clinical signs of cardiotoxicity appear, then treatment should be stopped immediately. If cardiac decompensation is suspected, a complete cardiac evaluationincluding a MUGA scanis warranted before the decision is made to continue treatment.54

Conclusions

Although conventional doxorubicin has demonstrated efcacy against a wide variety of tumor types, in some patients, it is associated with substantial cardiotoxicity that ranges from arrhythmias and nonspecic electrocardiogram changes to decreases in LVEF and cardiomyopathy. Because the lifetime cumulative dose of conventional doxorubicin should be limited to avoid increasing the risk of cardiotoxicity, some patients may not be treated with further doxorubicin therapy, even if they are likely to benet from such treatment. Several liposomal anthracyclines currently are available, including liposomal daunorubicin, nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin, and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin. Although these agents were developed with the purpose of maintaining antitumor efcacy and reducing cardiotoxicity, it should be noted that the extent of cardiac safety varies by agent. Based on published reports, the cardiac safety of liposomal daunorubicin remains unclear. Consequently, more studies will be needed to determine the maximum tolerated cumulative dose and its associated cardiac safety and clinical efcacy (especially in patients with a history of prior conventional anthracycline therapy). Evidence also has shown that nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin has better cardiac safety compared with conventional doxorubicin, even in patients who have received prior conventional doxorubicin treatment.

2062

CANCER May 15, 2004 / Volume 100 / Number 10

doxorubicin-induced congestive heart failure. Ann Intern Med. 1979;91:710 717. Wigler N, OBrien M, Rosso R, et al. Reduced cardiac toxicity and comparable efcacy in a Phase III trial of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (CAELYX/Doxil) vs. doxorubicin for rstline treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Poster presented at the 38th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, May 18 21, 2002, Orlando, Florida. Pharmacia & Upjohn Company. Adriamycin RDF/Adriamycin PFS (doxorubicin hydrochloride for injection) [package insert]. Kalamazoo, MI: Pharmacia & Upjohn Company, 2002. Launchbury AP, Habboubi N. Epirubicin and doxorubicin: a comparison of their characteristics, therapeutic activity and toxicity. Cancer Treat Rev. 1993;19:197228. Swain SM, Whaley FS, Ewer MS. Congestive heart failure in patients treated with doxorubicin: a retrospective analysis of three trials. Cancer. 2003;97:2869 2879. Shan K, Lincoff AM, Young JB. Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:4758. Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:783792. Ewer MS, Benjamin RS. Cardiac complications of cancer treatment. In: Bast RC, Kufe DW, Pollock RE, Weichselbaum RR, Holland JF, Frei E, editors. Cancer medicine. 5th edition. Ontario: BC Decker Inc., 2002:2330 2339. Legha SS, Benjamin RS, Mackay B, et al. Reduction of doxorubicin cardiotoxicity by prolonged continuous intravenous infusion. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96:133139. Birtle AJ. Anthracyclines and cardiotoxicity. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2000;12:146 152. Seymour L, Bramwell V, Moran LA. Use of dexrazoxane as a cardioprotectant in patients receiving doxorubicin or epirubicin chemotherapy for the treatment of cancer. The Provincial Systemic Treatment Disease Site Group. Cancer Prev Control. 1999;3:145159. Speyer JL, Green MD, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, et al. ICRF-187 permits longer treatment with doxorubicin in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:117127. Swain SM, Whaley FS, Gerber MC, Ewer MS, Bianchine JR, Gams RA. Delayed administration of dexrazoxane provides cardioprotection for patients with advanced breast cancer treated with doxorubicin-containing therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:13331340. Swain SM, Whaley FS, Gerber MC, et al. Cardioprotection with dexrazoxane for doxorubicin-containing therapy in advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:1318 1332. Gabizon A, Martin F. Polyethylene glycol-coated (pegylated) liposomal doxorubicin: rationale for use in solid tumours. Drugs. 1997;54(Suppl 4):1521. Tardi PG, Boman NL, Cullis PR. Liposomal doxorubicin. J Drug Target. 1996;4:129 140. Gilead Sciences, Inc. DaunoXome (daunorubicin citrate liposome injection) [package insert]. San Dimas, CA: Gilead Sciences, Inc., 2000. Elan Pharmaceuticals. Myocet (doxorubicin HCl liposome injection) product information. Princeton: Elan Pharmaceuticals, 2000. Ortho Biotech Products. Doxil (doxorubicin HCl liposome injection) [package insert]. Raritan: Ortho Biotech Products L.P., 2001.

However, the cardiac safety associated with liposomal encapsulation appears to be mitigated with the use of high bolus doses (i.e., 135 mg/m2). In addition, preliminary evidence suggests that the combination of nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin and trastuzumab has minimal cardiotoxicity. To date, the strongest evidence of cardiac safety with a liposomal anthracycline formulationfrom both prospective and retrospective studies can be derived from studies of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin. Based on endomyocardial biopsy and LVEF results, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin had improved cardiac safety compared with conventional doxorubicin, even in patients who received prior conventional doxorubicin treatment. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin is associated with a signicantly reduced risk of developing cardiac events compared with conventional doxorubicin (P 0.001), even with cumulative doses 500 mg/m2. Moreover, preliminary cardiotoxicity data suggest minimal cardiac events with the combination of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, docetaxel, and trastuzumab in patients with HER-2-positive metastatic breast carcinoma. The improved cardiac safety observed with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin is likely the result of enhanced tumor targeting, which reduces the likelihood of free doxorubicin concentrating in cardiac muscle.3 Liposomal anthracyclines represent an exciting development in cancer chemotherapy. Liposomal formulations, particularly pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, reduce the risk of cardiotoxicity observed with conventional doxorubicin without compromising antitumor activity, even when given in high cumulative doses. Moreover, there is also the potential for added benet when liposomal anthracyclines are used in combination with trastuzumab in patients with HER2-positive breast carcinoma.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11. 12.

13.

14.

15. 16.

17.

18.

REFERENCES

1. Pai VB, Nahata MC. Cardiotoxicity of chemotherapeutic agents: incidence, treatment and prevention. Drug Saf. 2000;22:263302. Balmer C, Valley AW. Basic principles of cancer treatment and cancer chemotherapy. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, Matzke GR, Wells BG, Posey LM, editors. Pharmacotherapy: a pathophysiologic approach. 3rd edition. Stamford. CT: Appleton & Lange, 1997:24032465. Waterhouse DN, Tardi PG, Mayer LD, Bally MB. A comparison of liposomal formulations of doxorubicin with drug administered in free form: changing toxicity proles. Drug Saf. 2001;24:903920. Maluf FC, Spriggs D. Anthracyclines in the treatment of gynecologic malignancies. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;85:18 31. Hortobagyi GN. Anthracyclines in the treatment of cancer: an overview. Drugs. 1997;54(Suppl 4):17. Von Hoff DD, Layard MW, Basa P, et al. Risk factors for

19.

2.

20.

21. 22.

3.

23.

4. 5. 6.

24.

Liposomal Anthracyclines/Theodoulou and Hudis

25. Harris L, Batist G, Belt R, et al. for the TLC D-99 Study Group. Liposome-encapsulated doxorubicin compared with conventional doxorubicin in a randomized multicenter trial as rst-line therapy of metastatic breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;94:2536. 26. Batist G, Ramakrishnan G, Rao CS, et al. Reduced cardiotoxicity and preserved antitumor efcacy of liposome-encapsulated doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide compared with conventional doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide in a randomized, multicenter trial of metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1444 1454. 27. Levine AM, Tulpule A, Espina BM, et al. A Phase I/II trial of liposomal doxorubicin (TLC D-99, Myocet) with cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone in newly diagnosed aggressive non-Hodgkins lymphoma [abstract 1133]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2002;21:284a. 28. Tulpule A, Espina BM, Dharmapala D, Boswell WD, Welles L, Levine AM. Treatment of newly diagnosed AIDS-related lymphomas with liposomal doxorubicin (TLC-D99, Myocet) combined with cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone: results of a Phase I/II trial [abstract 1135]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2002;21:285a. 29. Theodoulou M, Campos SM, Batist G, et al. TLC D-99 (D, Myocet) and Herceptin (H) is safe in advanced breast cancer: nal cardiac safety and efcacy analysis. Poster presented at the 38th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, May 18 21, 2002, Orlando, Florida. 30. Gabizon AA. Liposomal anthracyclines. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1994;8:431 450. 31. Gabizon AA, Muggia FM. Initial clinical evaluation of pegylated-liposomal doxorubicin in solid tumors. In: Woodle MC, Storm G, editors. Long circulating liposomes: old drugs, new therapeutics. New York: Springer-Verlag and Landes Bioscience, 1998:165174. 32. Working PK, Dayan AD. Pharmacological-toxicological expert report. CAELYX (stealth liposomal doxorubicin HCl). Hum Exp Toxicol. 1996;15:751785. 33. Berry G, Billingham M, Alderman E, et al. The use of cardiac biopsy to demonstrate reduced cardiotoxicity in AIDS Kaposis sarcoma patients treated with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin. Ann Oncol. 1998;9:711716. 34. Safra T, Muggia F, Jeffers S, et al. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil): reduced clinical cardiotoxicity in patients reaching or exceeding cumulative doses of 500 mg/m2. Ann Oncol. 2000;11:1029 1033. 35. Gabizon AA, Lyass O. Cardiac safety of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin demonstrated by endomyocardial biopsy in patients with advanced malignancies. Poster presented at the 39th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, May 31June 3, 2003, Chicago, Illinois. 36. Mustafa MH. Decreased risk of cardiotoxicity with longterm use of Doxil/Caelyx at high lifetime cumulative doses in patients with AIDS-related Kaposis sarcoma (KS) [abstract 2915]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2001;20:291b. 37. Gill PS, Espina BM, Muggia F, et al. Phase I/II clinical and pharmacokinetic evaluation of liposomal daunorubicin. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:996 1003. 38. Gill PS, Wernz J, Scadden DT, et al. Randomized Phase III trial of liposomal daunorubicin versus doxorubicin, bleomycin, and vincristine in AIDS-related Kaposis sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:23532364. 39. Money-Kyrle JF, Bates F, Ready J, Gazzard BG, Phillips RH, Boag FC. Liposomal daunorubicin in advanced Kaposis

2063

40.

41.

42.

43. 44.

45.

46. 47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

sarcoma: a Phase II study. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 1993; 5:367371. Cohen P, Gill PS, Wernz J, Scadden DT, Mukwaya GM, Sandhaus R. Absence of cardiac toxicity in patients who received 600 mg/m2 of liposomal encapsulated daunorubicin (DaunoXome) [abstract 761]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1997;16:217a. OByrne KJ, Thomas AL, Sharma RA, et al. A Phase I doseescalating study of DaunoXome, liposomal daunorubicin, in metastatic breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:1520. Fassas A, Buffels R, Anagnostopoulos A, et al. Safety and early efcacy assessment of liposomal daunorubicin (DaunoXome) in adults with refractory or relapsed acute myeloblastic leukaemia: a Phase III study. Br J Haematol. 2002; 116:308 315. Pratt CB, Ransom JL, Evans WE. Age-related Adriamycin cardiotoxicity in children. Cancer Treat Rep. 1978;62:13811385. Von Hoff DD, Rozencweig M, Layard M, Slavik M, Muggia FM. Daunomycin-induced cardiotoxicity in children and adults. A review of 110 cases. Am J Med. 1977;62:200 208. Lowis S, Lewis I, Elsworth A, Ablett S, Robert J, Frappaz D. Cardiac toxicity may limit the usefulness of liposomal daunorubicin (DaunoXome): results of a phase I study in children with relapsed or resistant tumoursa UKCCSG/SFOP study [abstract 435]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2002;21:109a. Lenaz L, Page JA. Cardiotoxicity of Adriamycin and related anthracyclines. Cancer Treat Rev. 1976;3:111120. Shapiro CL, Ervin T, Welles L, Azarnia N, Keating J, Hayes DF. Phase II trial of high-dose liposome-encapsulated doxorubicin with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in metastatic breast cancer. TLC D-99 Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:14351441. Billingham M, Bristow M. Evaluation of anthracycline cardiotoxicity: predictive ability and functional correlation of endomyocardial biopsy. Cancer Treat Symp. 1984;3:7176. Vogel CL, Cobleigh MA, Tripathy D, et al. Efcacy and safety of trastuzumab as a single agent in rst-line treatment of HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:719 726. Cobleigh MA, Vogel CL, Tripathy D, et al. Multinational study of the efcacy and safety of humanized anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody in women who have HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer that has progressed after chemotherapy for metastatic disease. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2639 2648. Baselga J, Tripathy D, Mendelsohn J, et al. Phase II study of weekly intravenous trastuzumab (Herceptin) in patients with HER2/neu-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 1999;26(4 Suppl 12):78 83. Trigo J, Climent MA, Lluch A, et al. Liposomal doxorubicin (Myocet) in combination with Herceptin and paclitaxel is active and well tolerated in patients with HER2-positive locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer (LA/MBC): a Phase II study. Poster presented at the 26th Annual San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, December 3 6, 2003, San Antonio, Texas. Wolff AC, Bonetti M, Sparano JA, Wang M, Davidson NE, on behalf of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Cardiac safety of trastuzumab (H) in combination with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (D) and docetaxel (T) in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer: preliminary results of ECOG 3198. Poster presented at the 39th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, May 31June 3, 2003, Chicago, Illinois. Safra T. Cardiac safety of liposomal anthracyclines. Oncologist. 2003;8(Suppl 2):1724.

You might also like

- Canadian Journal of DiabetesDocument227 pagesCanadian Journal of DiabetesAnatolia MaresNo ratings yet

- Nab Technology PDFDocument8 pagesNab Technology PDFalfox2000No ratings yet

- Irrational Use of Antibiotics and Role of The Pharmacist - An Insight From A Qualitative Study in New Delhi, India PDFDocument6 pagesIrrational Use of Antibiotics and Role of The Pharmacist - An Insight From A Qualitative Study in New Delhi, India PDFalfox2000No ratings yet

- INTERNATIONAL NONPROPRIETARY For Biological and Biotechnological Products PDFDocument35 pagesINTERNATIONAL NONPROPRIETARY For Biological and Biotechnological Products PDFalfox2000No ratings yet

- The Pharmacist - S Role in Preventing Antibiotic Resistance PDFDocument8 pagesThe Pharmacist - S Role in Preventing Antibiotic Resistance PDFalfox2000No ratings yet

- Emetogenic Potential of Antineoplastic Agents PDFDocument1 pageEmetogenic Potential of Antineoplastic Agents PDFalfox2000No ratings yet

- Guidelines For Tablet Crushing and Administration Via Enteral Feeding Tubes PDFDocument13 pagesGuidelines For Tablet Crushing and Administration Via Enteral Feeding Tubes PDFalfox2000No ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Computer First Term Q1 Fill in The Blanks by Choosing The Correct Options (10x1 10)Document5 pagesComputer First Term Q1 Fill in The Blanks by Choosing The Correct Options (10x1 10)Tanya HemnaniNo ratings yet

- CDKR Web v0.2rcDocument3 pagesCDKR Web v0.2rcAGUSTIN SEVERINONo ratings yet

- Portrait of An INTJDocument2 pagesPortrait of An INTJDelia VlasceanuNo ratings yet

- 09 WA500-3 Shop ManualDocument1,335 pages09 WA500-3 Shop ManualCristhian Gutierrez Tamayo93% (14)

- SPH4U Assignment - The Wave Nature of LightDocument2 pagesSPH4U Assignment - The Wave Nature of LightMatthew GreesonNo ratings yet

- Review of Related LiteratureDocument4 pagesReview of Related LiteratureCarlo Mikhail Santiago25% (4)

- CIR Vs PAL - ConstructionDocument8 pagesCIR Vs PAL - ConstructionEvan NervezaNo ratings yet

- QA/QC Checklist - Installation of MDB Panel BoardsDocument6 pagesQA/QC Checklist - Installation of MDB Panel Boardsehtesham100% (1)

- Research Article: Finite Element Simulation of Medium-Range Blast Loading Using LS-DYNADocument10 pagesResearch Article: Finite Element Simulation of Medium-Range Blast Loading Using LS-DYNAAnonymous cgcKzFtXNo ratings yet

- Aisladores 34.5 KV Marca Gamma PDFDocument8 pagesAisladores 34.5 KV Marca Gamma PDFRicardo MotiñoNo ratings yet

- A Novel Adoption of LSTM in Customer Touchpoint Prediction Problems Presentation 1Document73 pagesA Novel Adoption of LSTM in Customer Touchpoint Prediction Problems Presentation 1Os MNo ratings yet

- Laporan Praktikum Fisika - Full Wave RectifierDocument11 pagesLaporan Praktikum Fisika - Full Wave RectifierLasmaenita SiahaanNo ratings yet

- Assignment - 2: Fundamentals of Management Science For Built EnvironmentDocument23 pagesAssignment - 2: Fundamentals of Management Science For Built EnvironmentVarma LakkamrajuNo ratings yet

- Capital Expenditure DecisionDocument10 pagesCapital Expenditure DecisionRakesh GuptaNo ratings yet

- Case Assignment 2Document5 pagesCase Assignment 2Ashish BhanotNo ratings yet

- M2 Economic LandscapeDocument18 pagesM2 Economic LandscapePrincess SilenceNo ratings yet

- D - MMDA vs. Concerned Residents of Manila BayDocument13 pagesD - MMDA vs. Concerned Residents of Manila BayMia VinuyaNo ratings yet

- Ibbotson Sbbi: Stocks, Bonds, Bills, and Inflation 1926-2019Document2 pagesIbbotson Sbbi: Stocks, Bonds, Bills, and Inflation 1926-2019Bastián EnrichNo ratings yet

- Gabby Resume1Document3 pagesGabby Resume1Kidradj GeronNo ratings yet

- Hexoskin - Information For Researchers - 01 February 2023Document48 pagesHexoskin - Information For Researchers - 01 February 2023emrecan cincanNo ratings yet

- P394 WindActions PDFDocument32 pagesP394 WindActions PDFzhiyiseowNo ratings yet

- 21st Bomber Command Tactical Mission Report 178, OcrDocument49 pages21st Bomber Command Tactical Mission Report 178, OcrJapanAirRaidsNo ratings yet

- COOKERY10 Q2W4 10p LATOJA SPTVEDocument10 pagesCOOKERY10 Q2W4 10p LATOJA SPTVECritt GogolinNo ratings yet

- Delta AFC1212D-SP19Document9 pagesDelta AFC1212D-SP19Brent SmithNo ratings yet

- Are Groups and Teams The Same Thing? An Evaluation From The Point of Organizational PerformanceDocument6 pagesAre Groups and Teams The Same Thing? An Evaluation From The Point of Organizational PerformanceNely Noer SofwatiNo ratings yet

- Use of EnglishDocument4 pagesUse of EnglishBelén SalituriNo ratings yet

- Resume Jameel 22Document3 pagesResume Jameel 22sandeep sandyNo ratings yet

- Social Media Marketing Advice To Get You StartedmhogmDocument2 pagesSocial Media Marketing Advice To Get You StartedmhogmSanchezCowan8No ratings yet

- Lab 6 PicoblazeDocument6 pagesLab 6 PicoblazeMadalin NeaguNo ratings yet

- Action Plan Lis 2021-2022Document3 pagesAction Plan Lis 2021-2022Vervie BingalogNo ratings yet