Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Teaching Mark Twain

Uploaded by

shaharhr1Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Teaching Mark Twain

Uploaded by

shaharhr1Copyright:

Available Formats

Teaching Mark Twain's Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Shelley Fisher Fishkin

Despite the fact that it is the most taught novel and most taught work of American literature in American schools from junior high to graduate school, Huckleberry Finn remains a hard book to read and a hard book to teach. The difficulty is caused by two distinct but related problems. First, one must understand how Socratic irony works if the novel is to make any sense at all; most students don't. Secondly, one must be able to place the novel in a larger historical and literary context -- one that includes the history of American racism and the literary productions of African-American writers -- if the book is to be read as anything more than a sequel to The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (which it both is and is not); most students can't. These two problems pose real obstacles for teachers. Are they surmountable? Under some circumstances, yes. Under others, perhaps not. I think under most circumstances, however, they are obstacles you can deal with.

It is impossible to read Huck Finn intelligently without understanding that Mark Twain's consciousness and awareness is larger than that of any of the characters in the novel, including Huck. Indeed, part of what makes the book so effective is the fact that Huck is too innocent and ignorant to understand what's wrong with his society and what's right about his own transgressive behavior. Twain, on the other hand, knows the score. One must be skeptical about most of what Huck says in order to hear what Twain is saying. In a 1991 interview, Ralph Ellison suggested that critics who condemn Twain for the portrait of Jim that we get in the book

forget that "one also has to look at the teller of the tale, and realize that you are getting a black man, an adult, seen through the condescending eyes -- partially -- of a young white boy." Are you saying, I asked Ellison, "that those critics are making the same old mistake of confusing the narrator with the author? That they're saying that Twain saw him that way rather than that Huck did?" "Yes," was Ellison's answer.

Clemens as a child accepted without question, as Huck did, the idea that slaves were property; neither wanted to be called a "low-down Abolitionist" if he could possibly help it. Between the time of that Hannibal childhood and adolescence, however, and the years in which Twain wrote Huckleberry Finn, Twain's consciousness changed. By 1885, when the book was published, Samuel Clemens held views that were very different from those he ascribed to Huck. It might be helpful at this point to chart for your students the growth of the author's developing moral awareness on the subject of race and racism -- starting with some of his writings on the persecution of the Chinese in San Francisco (such as Disgraceful Persecution of a Boy), then moving through his marriage into an abolitionist family, the 1869 anti-lynching editorial that he published in The Buffalo Express entitled Only a Nigger, and his exposure to figures like Frederick Douglass and his father-in-law, Jervis Langdon.

By the time he wrote Huckleberry Finn, Samuel Clemens had come to believe not only that slavery was a horrendous wrong, but that white Americans owed black Americans some form of "reparations" for it. One graphic way to demonstrate this fact to your students is to share with them the letter Twain wrote to the Dean of the Yale Law School in 1885, in which he explained why he wanted to pay the expenses of Warner McGuinn, one of the first black law

students at Yale. "We have ground the manhood out of them," Twain wrote Dean Wayland on Christmas Eve, 1885, "and the shame is ours, not theirs, & we should pay for it."

Ask your students: why does a writer who holds these views create a narrator who is too innocent and ignorant to challenge the topsy-turvy moral universe that surrounds him? "All right, then, I'll go to Hell," Huck says when he decides not to return Jim to slavery. Samuel Clemens might be convinced that slavery itself and its legacy are filled with shame, but Huck is convinced that his reward for defying the moral norms of his society will be eternal damnation.

Something new happened in Huck Finn that had never happened in American literature before. It was a book, as many critics have observed, that served as a Declaration of Independence from the genteel English novel tradition. Huckleberry Finn allowed a different kind of writing to happen: a clean, crisp, no-nonsense, earthy vernacular kind of writing that jumped off the printed page with unprecedented immediacy and energy; it was a book that talked. Huck's voice, combined with Twain's satiric genius, changed the shape of fiction in America, and African-American voices had a great deal to do with making it what it was. Expose your students to the work of some of Twain's African-American contemporaries, such as Frederick Douglass, Charles Chesnutt, and Paul Laurence Dunbar. Those voices can greatly enrich students' understanding of both the issues Huckleberry Finn raises and the vernacular style in which it raises them.

If W.E.B. Du Bois was right that the problem of the twentieth century is the color line, one would never know it from the average secondary-school syllabus, which often avoids issues

of race almost completely. Like a Trojan horse, however, Huck Finn can slip into the American literature classroom as a "classic," only to engulf students in heated debates about prejudice and racism, conformity, autonomy, authority, slavery and freedom. It is a book that puts on the table the very questions the culture so often tries to bury, a book that opens out into the complex history that shaped it -- the history of the ante-bellum era in which the story is set, and the history of the post-war period in which the book was written -- and it requires us to address that history as well. Much of that history is painful. Indeed, it is to avoid confronting the raw pain of that history that black parents sometimes mobilize to ban the novel. Brushing history aside, however, is no solution to the larger challenge of dealing with its legacy. Neither is placing the task of dealing with it on one book.

We continue to live, as a nation, in the shadow of racism while being simultaneously committed, on paper, to principles of equality. As Ralph Ellison observed in our interview, it is this irony at the core of the American experience that Mark Twain forces us to confront head-on.

History as it is taught in the history classroom is often denatured and dry. You can keep your distance from it if you choose. Slaveholding was evil. Injustice was the law of the land. History books teach that. But they don't require you to look the perpetrators of that evil in the eye and find yourself looking at a kind, gentle, good-hearted Aunt Sally. They don't make you understand that it was not the villains who made the system work, but the ordinary folks, the good folks, the folks, who did nothing more than fail to question the set of circumstances that surrounded them, who failed to judge that evil as evil and who deluded themselves into thinking they were doing good, earning safe passage for themselves into heaven.

When accomplished fiction writers expose the all-too-human betrayals that well-meaning human beings perpetrate in the name of business-as-usual, they disrupt the ordered rationalizations that insulate the heart from pain. Novelists, like surgeons, cut straight to the heart. But unlike surgeons, they don't sew up the wound. They leave it open to heal or fester, depending on the septic level of the reader's own environment.

Irony, history, and racism all painfully intertwine in our past and present, and they all come together in Huck Finn. Because racism is endemic to our society, a book like Huck Finn, which brings the problem to the surface, can explode like a hand grenade in a literature classroom accustomed to the likes of Macbeth or Great Expectations -- works which exist at a safe remove from the lunchroom or the playground. If we lived in a world in which racism had been eliminated generations before, teaching Huck Finn would be a piece of cake. Unfortunately that's not the world we live in. The difficulties we have teaching this book reflect the difficulties we continue to confront in our classrooms and our nation. As educators, it is incumbent upon us to teach our students to decode irony, to understand history, and to be repulsed by racism and bigotry wherever they find it. But this is the task of a lifetime. It's unfair to force one novel to bear the burden -- alone -- of addressing these issues and solving these problems. But Huck Finn -- and you -- can make a difference.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- ERISA Class Notes (Spring 2011) - 1Document107 pagesERISA Class Notes (Spring 2011) - 1shaharhr1100% (1)

- The Lord of The RingsDocument5 pagesThe Lord of The RingsSD0% (5)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Margaret Atwood - PenelopiadDocument33 pagesMargaret Atwood - Penelopiadgoldfish075% (4)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Barbri Corp OutlineDocument12 pagesBarbri Corp Outlineshaharhr1100% (3)

- HAND OUT1 Intro To Literary GenresDocument3 pagesHAND OUT1 Intro To Literary Genresmarco_meduranda100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- 2nd Grade Spelling Words Week 1Document9 pages2nd Grade Spelling Words Week 1ShekinNo ratings yet

- 9h Study Guide To Kill A MockingbirdDocument15 pages9h Study Guide To Kill A Mockingbirdapi-331810107No ratings yet

- 21st Century Literature from the Philippines and Around the World (2S SY 18-19Document38 pages21st Century Literature from the Philippines and Around the World (2S SY 18-19Yssa SayconNo ratings yet

- The Butterflys Evil Spell ScriptDocument36 pagesThe Butterflys Evil Spell Scriptanlsta0% (1)

- Junie B Jones and Some Sneaky Peeky SpyingDocument9 pagesJunie B Jones and Some Sneaky Peeky SpyingTeta Ida0% (2)

- HANSEL AND GRETELDocument48 pagesHANSEL AND GRETELCarla_con_C100% (1)

- CBSE Class 11 English Core Sample Paper-01Document7 pagesCBSE Class 11 English Core Sample Paper-01cbsesamplepaper80% (5)

- The Enemy Within - Developer Diary #18Document5 pagesThe Enemy Within - Developer Diary #18Augusto Santana0% (1)

- Evolution Manual - Fixed Assets PDFDocument44 pagesEvolution Manual - Fixed Assets PDFshaharhr1No ratings yet

- DETAILED LESSON PLAN ENGLISH 6 Week 6Document12 pagesDETAILED LESSON PLAN ENGLISH 6 Week 6Mark Prian Iposada100% (1)

- Eric Lustbader Ninja PDFDocument2 pagesEric Lustbader Ninja PDFVanessa0% (1)

- The Characters of El FilibusterismoDocument23 pagesThe Characters of El FilibusterismoDonna VillarosaNo ratings yet

- Edifact SampleDocument1 pageEdifact Sampleshaharhr1No ratings yet

- Upgrade Exact To A Newer VersionDocument2 pagesUpgrade Exact To A Newer Versionshaharhr1No ratings yet

- EFT SOP 19 December 2006Document20 pagesEFT SOP 19 December 2006shaharhr1No ratings yet

- Here Are A Few Different Methods.: Method 1Document2 pagesHere Are A Few Different Methods.: Method 1shaharhr1No ratings yet

- Add merchants to credit card reportsDocument4 pagesAdd merchants to credit card reportsshaharhr1No ratings yet

- SOP - Install ExactDocument5 pagesSOP - Install Exactshaharhr1No ratings yet

- SOP - Checking Bank LinksDocument4 pagesSOP - Checking Bank Linksshaharhr1No ratings yet

- Fastnet Radio Pad SetupDocument5 pagesFastnet Radio Pad Setupshaharhr1No ratings yet

- Regression With Dummy Variables Econ420 1Document47 pagesRegression With Dummy Variables Econ420 1shaharhr1No ratings yet

- Self-Study Training Material & Assessment PricesDocument5 pagesSelf-Study Training Material & Assessment Pricesshaharhr1No ratings yet

- Recall A Tendered Order - Reprint A Receipt:: Kumnandi Food CompanyDocument5 pagesRecall A Tendered Order - Reprint A Receipt:: Kumnandi Food Companyshaharhr1No ratings yet

- Principles of Accounting I: Jackson Community College ACCOUNTING 231-02 Winter 2013Document8 pagesPrinciples of Accounting I: Jackson Community College ACCOUNTING 231-02 Winter 2013shaharhr1No ratings yet

- Call Centre Manual 04052007Document27 pagesCall Centre Manual 04052007shaharhr1No ratings yet

- Business Analytics For Pastel EvolutionDocument4 pagesBusiness Analytics For Pastel Evolutionshaharhr1No ratings yet

- HelloDocument1 pageHelloshaharhr1No ratings yet

- 10 Reasons To Buy Pastel EvolutionDocument1 page10 Reasons To Buy Pastel Evolutionshaharhr1No ratings yet

- Review of Bas Stats For Econometric SuccessDocument42 pagesReview of Bas Stats For Econometric Successshaharhr1No ratings yet

- Binder clientBasedLawyeringDocument9 pagesBinder clientBasedLawyeringshaharhr1No ratings yet

- Spectroscopy I (1a)Document6 pagesSpectroscopy I (1a)shaharhr1No ratings yet

- Spectroscopy I (1a)Document6 pagesSpectroscopy I (1a)shaharhr1No ratings yet

- Business Associations Fall 2010 Fendler OutlineDocument121 pagesBusiness Associations Fall 2010 Fendler OutlineJoshua Ryan Collums100% (1)

- Maths Class 11Document7 pagesMaths Class 11shaharhr1No ratings yet

- History of Electric VehiclesDocument8 pagesHistory of Electric Vehiclesshaharhr1No ratings yet

- Advertisements - The CBSE Way: Format and Marking SchemeDocument5 pagesAdvertisements - The CBSE Way: Format and Marking Schemeshaharhr1No ratings yet

- Yahoo! Sports: Baseball Chicago CubsDocument3 pagesYahoo! Sports: Baseball Chicago Cubsshaharhr1No ratings yet

- K. D. Verma (Auth.) - The Indian Imagination - Critical Essays On Indian Writing in English (2000, Palgrave Macmillan US)Document278 pagesK. D. Verma (Auth.) - The Indian Imagination - Critical Essays On Indian Writing in English (2000, Palgrave Macmillan US)Anik DasNo ratings yet

- Grammar Year 4 SKBR QuestionsDocument4 pagesGrammar Year 4 SKBR QuestionsFadhilah AiniNo ratings yet

- Fce Reading Answer Key 2Document3 pagesFce Reading Answer Key 2keer2441998No ratings yet

- Gullivers Travels in LilliputDocument5 pagesGullivers Travels in LilliputPASTOBRAS MEXICO SA DE CVNo ratings yet

- Watch That Time I Got Reincarnated As A Slime English SubDub Online Free On Zoro - ToDocument1 pageWatch That Time I Got Reincarnated As A Slime English SubDub Online Free On Zoro - ToBraylen MilsteadNo ratings yet

- Shakespeare's 'The Winter's Tale' Explores Pastoral TraditionDocument7 pagesShakespeare's 'The Winter's Tale' Explores Pastoral TraditionTanatswa ShoniwaNo ratings yet

- Past Progressive Story 2Document8 pagesPast Progressive Story 2rodo25100% (1)

- General Comprehension Questions For Any Book 2020Document5 pagesGeneral Comprehension Questions For Any Book 2020Rafael MattozoNo ratings yet

- The Art of AnimeDocument15 pagesThe Art of Animecv JunksNo ratings yet

- PROSEDocument2 pagesPROSEArianiNo ratings yet

- DialogueDocument5 pagesDialogueisabelo zamora jrNo ratings yet

- Submission Guidelines: The Oerth JournalDocument5 pagesSubmission Guidelines: The Oerth JournalJoan FortunaNo ratings yet

- Dickinson CatreflectionDocument2 pagesDickinson Catreflectionapi-240429775No ratings yet

- Classifications of LiteratureDocument1 pageClassifications of LiteratureMichael RamirezNo ratings yet

- Work WWW PDF s7 I Intransitive-Verb-listDocument3 pagesWork WWW PDF s7 I Intransitive-Verb-listNinik Triayu SNo ratings yet

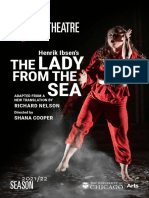

- Court Theatre The Lady From The Sea ProgramDocument19 pagesCourt Theatre The Lady From The Sea ProgramIvan BaleticNo ratings yet