Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Shao, Y.

Uploaded by

jomanousOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Shao, Y.

Uploaded by

jomanousCopyright:

Available Formats

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis.

Permission is given for

a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and

private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without

the permission of the Author.

Using data from fourteen Pacific Rim

countries to prove: The Relationship

between World Financial Crises and

Leverage

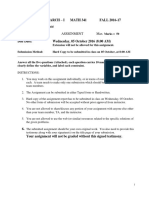

A research report presented in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the degree of

Master of Finance

At Massey University, Palmerston North

New Zealand

Yingying Shao

2013

Abstract

This paper aims to test the relationship between firm leverage and crises in fourteen Pacific

Rim countries (with fifteen markets) since 1985 to 2011, and to check whether firms change

their debt level during crises periods. Annual data are collected from Datastream. My results

show firms with positive relation between individual stock return and exchange rate of J apan

decrease their debt-level in the 1987 Black Monday in country level, industries like Oil &

Gas, Basic Materials, Industrials and Consumer Goods decrease debt-level during 1985 to

1991. In firms with negative exchange rate exposure, Philippines decreases debt ratio during

2004 to 2011, Russia increases its debt ratio in the same period in country level; Consumer

Goods decrease its debt ratio in since 1985 to 1991 and increase its debt ratio since 1994 to

2001 in industry level. The remaining countries or industries change their leverage are based

on change of market value of their firms, not the change of debt-to-value ratios.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the people who have helped and supported me in my research

report.

At first, I am grateful for my supervisor Dr. J G Chen. He has given me lots of valuable

advices on how to build regression model and how to use SAS software. His encouragement

and suggestions help me to finish my research and overcome difficulties.

At second, I would like to thank FongMee Chin; she gives me lots of help in using

Datastream.

At last, I also would like to thank to my friends Xiaojing Kong and Weiwei Cai. They give

lots of suggestions to me in solving problems. They accompany me make me enjoy studying

in library. In addition, I would like to be grateful for my parents, without their supporting, I

could not finish my Master of Finance.

Table of Contents

Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 2

Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... 3

List of Tables ............................................................................................................................. 5

1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 6

2. Background ......................................................................................................................... 8

2.1. 1987 Black Monday .................................................................................................... 8

2.2. 1997 Asian Financial Crisis ........................................................................................ 8

2.3. Subprime Crisis ........................................................................................................... 9

2.4. European Sovereign-debt Crisis ................................................................................ 11

3. Literature Review ............................................................................................................. 12

3.1. Exchange rate exposure ............................................................................................. 12

3.2. Firm Leverage ........................................................................................................... 14

3.2.1. Book value of Leverage vs. Market value of Leverage ..................................... 14

3.2.2. Leverage and Crisis............................................................................................ 15

3.2.3. Other Variables .................................................................................................. 17

4. Data ................................................................................................................................... 22

4.1. Collection of Data ..................................................................................................... 22

4.2. Determinants of Variables ......................................................................................... 22

4.3. Correlation between variables ................................................................................... 24

5. Methodology ..................................................................................................................... 25

5.1. Exchange rate exposure ............................................................................................. 25

5.2. Firm Leverage ........................................................................................................... 25

5.3. Hypothesis ................................................................................................................. 26

6. Empirical results and discussions ..................................................................................... 27

6.1. Exchange rate exposure ............................................................................................. 27

6.2. Firm Leverage in Crises ............................................................................................ 28

7. Conclusion ........................................................................................................................ 33

Tables ....................................................................................................................................... 35

Reference ................................................................................................................................. 50

List of Tables

Table 1 Sample Description...

...37

Table 2 Summary Statistic..

...38

Table 3 Correlation.

...39

Table 4 Regression results for exchange rate exposure..

...40

Table 5 Regression results for firm leverage in country level...

...42

Table 6 Regression results for firm leverage in industry level...

...44

Table 7 Regression results of firm leverage for J apan in Crisis I...

...46

Table 8 Regression results of firm leverage for Thailand in Crisis II...

...47

Table 9 Regression results of firm leverage for negative exposure group in Crisis III..

...48

Table 10 Regression results of firm leverage for positive exposure group in Crisis III.

...50

1. Introduction

Leverage plays a crucial role in finance, it is a popular word mentioned by economists.

Leverage can multiply gains and losses for any technique. Common ways are borrowing

money, buying fixed assets and using derivatives. A public corporation can leverage its

equity by borrowing money, the more it borrows, the less equity capital it needs; risk will

increase simultaneously.

The relation of debt-level in crisis is a global issue. With economic globalization, each

country may face to crises. For example, shortage of money in Industrial and Commercial

Bank of China becomes headlines in recent, as one of the biggest banks in China, some

economists indicate it is a forerunner for financial crisis. Each time when the crisis appears, it

will bring bad memory to the whole world. Hence, another popular world I will mention is

crises. Since late in 2009, some countries in Europe like Greece, Portugal, Italy, Ireland,

Spain, etc. are affected by the Sovereign-Debt Crisis; following with crises, increasing

unemployment, poverty bubbles, and corporates bankruptcy appear, some politicians in

European countries even leave their stage because of the sovereign debt crisis.

This paper is concentrate in researching the relationship between crises and firm leverage, to

test whether firms change their debt level during crises periods. Lots of previous papers study

the relations of debt ratio among profitability, growth opportunities, firm size, etc., not many

of them illustrate relation between crises and leverage. Therefore, I include five extra

explanatory variables as well: profitability, growth opportunities, firm size, tangibility and

current ratio.

Annual data used in the paper come from Datastream, it includes fourteen Pacific Rim

countries (with fifteen markets, market of China and Hong Kong is separated) from 1985 to

2011. During these 26 years, four crises have huge effect on the whole world, they are 1987

Black Monday, 1997 Asian Crisis, Subprime Crisis in 2007, and European Sovereign-debt

Crisis. No explicit bound for the last two crises, for this reason, I separate 26 years into three

crises periods, 1985 to 1991, 1994 to 2001, and 2004 to 2011.

My research process is divided into two parts. In the first part, I use the relation between

exchange rate and stock returns to divide firms into two groups positive and negative

based on their betas of exchange rates, firms in different groups have different reaction to

currency depreciations, hence, they also have different reaction to change of debt-to-value

ratio during crises; then separate them into ten industries. In the second part, I use six

variables (dummy variable crises year, and five extra variables) that have effect on leverage

to have tests on each group. By examining different groups in different countries, I would

like to know if there has any regular or special relation among them.

In exchange rate exposure test, Crisis II (1994 2001) shows results of negative exposure

group is more significant than positive exposure group, Crisis III (2004 -2011) shows

opposite results, positive exposure group is more significant than negative exposure group.

In firm leverage test, my results show positive exposure group of J apan decrease their debt-

level in Crisis I (1985 1991) in country level, Oil & Gas, Basic Materials, Industrials and

Consumer Goods decrease debt-level during Crisis I in industry level; all of them are

consistent with my hypothesis. In negative exposure group, Philippines decreases debt ratio

in Crisis III, Russia increases its debt ratio in Crisis III in country level; Consumer Goods

decrease debt ratio in Crisis I and increase debt ratio in Crisis II in industry level.

The remaining paper is structured as follows: Section II illustrates the previous literatures

about relationship between stock returns for individual firms and foreign exchange rate in

their own countries; also the relations among leverage, crisis, and other control variables.

Section III introduces data definitions and its collections; the following part, Section IV

displays two regression models for testing these relations, and hypotheses in my research.

Section V is the discussion of the empirical results; the findings of the research are

summarized in Section VI. All summary for papers and implications are illustrated in the last

section, Section VII.

2. Background

2.1. 1987 Black Monday

Date: Black Monday refers to Monday October 19

th

, 1987, when stock markets around the

world collapsed, the stock market, along with the associated futures and options markets,

crashed, with the S&P 500 stock market index falling about 20 per cent.

Area Extent: The crash begins in Hong Kong and spreads west to Europe, hits the United

States after other markets have already declined by a significant margin. By 11

th

November

1987, stock market in Hong Kong has fallen 45.5%, J apan 19.8%, Australia 43.4%, West

Germany 38.4%, the United Kingdom 27.2%, the United States 27.8%, and Canada 28.4%.

New Zealand's market is hit especially hard, falling about 60% from its 1987 peak.

Causes: Economists believe potential causes for the declining include program trading,

overvaluation, illiquidity, and market psychology. In the book of Allen (2009), Allen

concludes the most commonly mentioned of the worlds stock markets crash: a) speculation

drives stock market unstable, a major of funds shift out of stocks into other investments, such

as bonds; b) investors lost confidence in the economies of the US government, especially for

reducing the federal budget deficit and to maintain the foreign exchange value of the US

dollar; c) lots of international investors move their money out of US stock market for fearing

much loss of the US dollar value. While the US stock market crashes, fear spreads to all other

markets; d) Allen also shows another explanation that has been less mentioned, on 22

October 1987, the editorial page of The Wall Street J ournal carried two articles by prominent

economists, one claiming that the crash occurred because monetary policy was too restrictive, and one

claiming that the crash occurred because monetary policy was too loose.

In addition, wind disaster on October 16

th

, 1987 (one week earlier than Black Monday) is also

regarded as one reason for this crisis.

Effects: The Black Monday decline is the largest one-day percentage decline in the Dow

J ones. It causes the economic panic and recession at the end of 1980s.

2.2. 1997 Asian Financial Crisis

Date: 1997 Asian Financial Crisis is also called Southeast Asia Financial Crisis. The crisis

starts on J uly 10

th

, 1997, after the financial collapse of Thailand; Thai government is forced

to float the Thai baht, cutting its peg to the U.S. dollar.

Area Extent: The crisis affects mainly in Asia. As the crisis spreads, most Southeast Asian

and J apan see slumping currencies, devaluing stock markets and other asset prices. Indonesia,

South Korea and Thailand are the countries most affected by the crisis. Hong Kong, Malaysia,

Laos and Philippines are also hurt by the slump. China, Singapore, Brunei and Vietnam are

less affected.

Causes: CSR report shows the crisis begins with two rounds of currency depreciations in

early summary 1997. The first round is a sharply drop in the value of the Thai baht, Malaysia

ringgit, Philippines peso, and Indonesian rupiah. After these currencies staying at lower

values, the second round comes with downward value of Taiwan dollar, South Korean won,

Brazilian real, Singaporean dollar, and Hong Kong dollar. In countering the downward values

of currencies, governments sell foreign exchange reserves they have, buy their own

currencies, and raise interest rates to prevent speculators and to attract foreign capital. The

higher interest rates have slowed economic growth and made interest-bearing securities more

attractive than equities. As a result, stock price falls.

CSR attributes the Asian financial crisis to four basic problems or issues: a) a shortage of

foreign exchange in Thailand, Indonesia, South Korea and other Asian countries that has

caused the value of currencies and equities to fall dramatically; b) inadequately developed

financial sectors and mechanisms for allocating capital in the troubled Asian economies; c)

effects of the crisis on both the United States and the whole world; d) and the role, operations,

and replenishment of funds of the International Monetary Fund.

Effects: The crisis has significant macroeconomic-level effects, including sharp reductions in

values of currencies, stock markets, and other asset prices of several Asian countries. It also

leads to a political upheaval, most notably culminating in the resignations of President

Suharto in Indonesia and Prime Minister General Chavalit Yongchaiyudh in Thailand.

2.3. Subprime Crisis

Date: Subprime Crisis is also called Subprime Mortgage Crisis that starts in America since

2006; it spreads to main financial regions like Europe Union and J apan in August 2007.

Area Extent: The main area of the crisis is the U.S.; then it spreads to the important financial

centres worldwide.

Causes: Direct reason for the crisis is the interest rate increasing and real estate decreasing.

Potential causes include over-consumption in accelerating economic growth, increasing gap

between rich and poor, over-debt or mortgage for consumption.

Murthy and Deb (2008) explain how housing bubbles cause the crash in stock price: the

remodelled financial system has made credit available to more people, which leads to higher

asset prices and value of collateral, in turn, loans appear to be safer. The roots of crisis come

from the decreasing of interest rate. With rising in the interest rate, the mortgage payments

rise and defaults among the subprime category of borrowers increase as well. When attempts

are made to recover dues, it is realized that there are very few buyers of the mortgaged

property due to increased mortgage costs. A recession develops in the housing sector and

finally it is transmitted to the entire US economy through securitization of mortgage

payments. The collapse of the U.S. Housing Bubble has a direct impact not only on home

valuations, but also on the nation's mortgage markets, home builders and home supply retail

outlets. This leads to the emergence of a nationwide recession, creates an unprecedented

situation characterized by credit crunch, bankruptcy, stock price crashing and price of dollar

falling. It is the failure of the response of the financial sector in the form of financial

innovation in the garb of derivatives, which fails to contain risks of lending.

Effects: For the U.S., lots of firms declare bankruptcy; stock index, home equity and housing

price decrease sharply. For the whole world, the crisis causes panic in financial markets and

encourages investors to take their money out of risky mortgage bonds and puts it into

commodities as "stores of value". In addition, the U.S. subprime mortgage crisis is a set of

events and conditions that lead to the late-2000s financial crisis, characterized by a rise in

subprime mortgage delinquencies and foreclosures, and the resulting decline of securities

backed by mortgages.

2.4. European Sovereign-debt Crisis

Date: European Sovereign-debt crisis referred to continues of 2007 Subprime crisis, it is an

on-going financial crisis that has made it difficult or impossible for some countries in the

euro area to repay or re-finance their government debt without the assistance of third parties.

Area Extent: In late 2009 and early 2010, Fitch, Moodys and Standard & Poors lower the

sovereign debt rating of Greece, which cause the crisis in Greece exploded. Subsequently,

Ireland, Portugal, Italy, and Spain are involved in the same situation, also the Germany and

France. Then, the debt crisis spreads to the whole Europe.

Causes: As a continue crisis of the Subprime Crisis in 2007, the causes of the debt crisis

could be attributed to rise household and government debt level, grow trade imbalances (trade

deficit), structural contradiction of Eurozone system, monetary policy inflexibility and loss of

confidence of countries creditworthiness.

Causes of the debt crisis varied by country. For example, in Greece, high public sector wage

and pension commitments are related to the debt increase. In Ireland, the sovereign debt crisis

is not based on government over-spending, but from the state guaranteeing the six main Irish-

based banks who have financed a property bubble. In addition, the structure of the Eurozone

as a monetary union also contributed to the crisis and harmed the ability of European leaders

to respond.

Effects: Although the crisis is still on-going, it already has huge impact on politics in

European countries elections. In 2011, five countries that affected by sovereign debt crisis

change their governments, such as Papandreou (Greece), Socrates (Portugal), Berlusconi

(Italy), Cowen (Ireland), Zapater (Spain), etc., all of them have to leave their political stage.

3. Literature Review

3.1. Exchange rate exposure

Each firm has different reaction while the exchange rate fluctuates, which is relative to their

business area. Studies of Aghion et al. (2001), Krugman (1999), and Bris and Koskinen (2002)

prove that firms either suffer or benefit from currency depreciation depending on their

exchange rate exposure. According to these studies, I suggest some firms may benefit from

currency fluctuates, others have opposite reactions. For supporting my opinion, I find several

literatures to show the relationship between exchange rate and stock returns.

Early studies of Aggarwal (1981), Soenen and Hennigar (1988) illustrate the relationship

between exchange rate and stock returns by considering the correlation between two variables:

exchange rates and stock returns. Their results show that, because of the multinational

characteristic of the frim, exchange rate would affect a firms foreign operation and total

profits, which therewith, affect its stock price. In the contrary, a general downward

movement of the stock market may lead investors to seek for better returns; which also

decrease the demand for money, lower the interest rates, cause further outflow of funds and

hence depreciate the currency. Bodnar and Wong (2003) estimate exchange rate coefficient

will provide a measure of the effect of exchange rate changes on the stock returns given its

relation to the market return index.

Lots of papers indicate relation of stock returns and exchange rate exposure in different

markets may lead different results.

Najang and Seifert (1992) employ GARCH framework for daily data from the U.S, Canada,

the UK, Germany and J apan, show stock returns have positive effects on exchange rate

volatility. Abdalla and Murinde (1997) suggest in India, Korea and Pakistan, exchange rate

can affect stock prices by using data form 1985 to 1994; inversely, for the Philippines, the

stock prices affect the exchange rates. The same result also appears in the research of Ajayi et

al. (1998), by investigating for seven advanced markets from 1985 to 1991 and eight Asian

emerging markets from 1987 to 1991, they get the unidirectional causality in all the advanced

economies, but with inconsistent causal relations in the emerging economies, and they

explain the different results by the differences in the structure and characteristics of financial

markets between these two groups. Similarly, Nieh and Lee (2001) examine this kind of

relation from G-7 countries for the period from October 1, 1993 to February 15, 1999. They

cannot find long-run equilibrium relationship for each G-7 country, but one days short-run

equilibrium relationship has been found for each G-7 country. These results may be explained

by each countrys differences in economic stage, government policy, expectation pattern, etc.

Different industries also show different relations. J orion (1991) has investigated the

sensitivity of stock prices of multinational corporates in the US to changes in US dollar

exchange rate, J orions findings show that some industries, like Chemical and Machinery,

which export a significant proportion of their production or have significant foreign

operations, benefit from the depreciation of the dollar and suffer from the dollars

appreciation. In addition, Fang and Loo (1994) state relations among exchange rate, stock

prices and industries as well; they choose 20 US industries common stock returns since

J anuary 1981 to December 1990. The result shows the exchange rate changes have a negative

influence effect on common stock returns in industries like mining, food and beverage,

chemical, petroleum, and utilities. Conversely, industries such as textile and apparel,

machinery, transportation equipment, department stores, other retail trade, banking, finance

and real estate, and miscellaneous have opposite reaction. Bodnar and Gentry (1993) using

industry portfolios for the United States, J apan and Canada find exchange risk exposure to be

positive (negative) for exporting (importing) industries.

El-Masry (2003) regard a change in real exchange rates, are likely to affect a firms future

expected cash flows and future value; hence the impact of exchange rate movements on stock

returns can extend over a number of periods. The author run regression of stock returns of

industries on lagged exchange rate changes and finds strong evidence between lagged

exchange rate exposure and stock returns. Bartoy and Bodnar (1994) suggest that although

the exchange risk was priced in equity market, the market was not fully efficient with respect

to exchange rate changes, so it might take time to incorporate all the implications of foreign

exchange rate movements. Hence, they considered to add lag in value of changes in the home

currency, which were more meaningful for establishing a pricing relationship that

contemporaneous changes. Similarly, Amihud (1994) report that exchange rate fluctuations

affect the stock returns only with lags of up to two quarters. However, Krishnamoorthy (2001)

also has opposite opinion with Bartoy and Bodnar (1994); they find insignificant relation

between lagged exchange rate changes and stock prices. He and Ng (1998) consider that add

lag to exchange rate cannot affect the results.

Studies above are used to prove the relation between exchange rate exposure and stock

returns are exist. For sorting the firms into two groups by using their relation, we should have

more evidence about the methodology.

Bris et al. (2004) offer the way to divide firms into two groups by using individual companies

stock market returns. In the first group they have companies whose stock returns decrease

when the domestic currency appreciates with respect to the U.S. dollar (negative exposure

companies), and in the second group they place those companies whose stock returns increase

(positive exposure companies). The first group includes exporting firms and firms in the

tradable sector in general, while the second group includes importing firms, firms finance

with large amounts of foreign debt and firms in the non-tradable sector.

3.2. Firm Leverage

A leveraged investment is one that may put more risk in the risk. Leverage can enhance

risk, but when it is successfully employed it offers great benefit for little cost. Robert G.

Bowman (1980) indicates leverage (debt-to-equity ratio) is an important variable in issues

concerning the risk of a firm and its securities. Hamada (1969) has demonstrated theoretically

the relationship between leverage and systematic risk.

In the book of Krefetz (1985), there shows a poem written by William Blake, a metaphysical

poet, You never know how much is enough until you know how much is too much. If the

poet is here today, Blake undoubtedly would be an advocate of leverage. Leverage has a way

of telling one how much is enough. Krefetz also trusts leverage is an increasingly popular

financial technique since it is applicable to all markets. Its growing appeal is twofold: it is

used by those who would employ more risk to increase their rate of return; and it is used by

those who wish to manage risk more prudently. Though it may sound contradictory,

leverage can be used in a speculative fashion or a conservative one, depending on ones goals.

3.2.1. Book value of Leverage vs. Market value of Leverage

Firm leverage here can be calculated with book value or market value; these two methods

may lead to different results. Hence, I tried to find some articles to see which one is better in

illustrating the variable leverage.

Bowman (1980) indicates the leverage of a firm is important to consider risk; besides, the

market rate of interest is an important determinant of the market value debt, so the variable

should be measured using market values. Bowman examines whether the use of market

measures improve the empirical association between systematic risk and financial leverage

(debt-to-equity ratio). However, his results are contrary to his expectations; Bowman (1980)

finds the use of market value measures of debt does not significantly improve the association

between financial leverage and beta. The finding cannot reflect sufficient differences between

book value of debt and market value of debt which exists at that time. Mulford (1985)

suggests the failure of Bowman (1980) to find evidence of superior performance for a debt-

to-equity ratio based on market values of debt may have been due to small differences

between the book and market values of debt which accompanied the general level of interest

rates at that time. Hence, Mulford increases the size of differences between book and market

values of debt. With a better conclusion, the new results are more consistent with Bowmans

original expectations. The market value of leverage ratios has a greater association with

market beta than did their book-market-based counterparts.

In addition, Mulford (1985) also considers firm capital structure (i.e. financial leverage) and

systematic risk have positive relations. Others like Beaver, Kettler, and Scholes (1970),

Rosenberg and McKibben (1973), etc. also have empirical tests to support this relationship.

3.2.2. Leverage and Crisis

J ensen and Meckling (1976) show high levels of debt can lead to over-investment in risky

projects. Andrade and Kaplan (1998) suggest that firms with extreme levels of leverage are

more likely to be in distress and these firms would be most affected by an economic

downturn. Likewise, an event study by Opler and Titman (1994) select firms in industries

experiencing financial distress, and find the more highly leveraged of these firms experience

a greater decline in sales than their lower leverage counterparts.

Recently, Tan (2012) also uses data from 227 firms from eight Asian economies to study the

relationship between financial distress and firm performance during the Asian Financial

Crisis of 1997-1998. He uses leverage to proxy for financial distress. Tan finds that the

relationship between firm performance and financial leverage is negative; firms with low

financial leverage outperform have high financial leverage. Besides, in Tans paper, for

measuring the leverage-performance sensitivity between the crisis and non-crisis periods, he

add an interaction term that Crisis*leverage to his original model to check the whether the

firm leverage and performance is sensitive to crisis, the result shows the leverage-

performance relationship is sensitive during crisis period, and the relationship is negative

between firm performance and financial leverage.

Bris and Koskinen (2001) establish a model to examine the causal relationship between

exporting firms capital structure and exchange rate policy. They find the exporting firms

display increasing leverage prior to currency crises in countries with fixed exchange rate,

which is the same with the research in the 1997 Asian crises by Pomerleano (1999).

Bris, Koskinen, and Pons-Sanz (2004) use data from 17 countries that have suffered a

currency crisis to measure the relation between firm-level leverage and currency crisis. They

indicated that the negative exchange rate exposures firms had higher leverage prior to a crisis

while compared with the firm with positive exchange rate betas. Besides, they even report

firm level debt-to-value-ratios country by country and on a regional level. For example, in

Europe, there was not much change in the leverage level after the crisis; but Asia and Latin

America both have an opposite reaction, they exhibit a significant increase in debt-to-value

ratios. Then, they sort firms into two groups with different coefficients of exchange rate

exposure; the results show firms that have negative exposure may increase their leverage

more than positive exposure firms.

Firms with high leverage have relatively low equity levels, implying lower management

ownership. According to J ensen and Meckling (1976), firms not 100% owned by their

managers incur agency costs, which is the managers of these firms are less likely to make

optimal decisions and more likely to engage in risky projects. If those projects do not pay off,

firm performance will be adversely affected. Consistent with this view, firm leverage is

associated with significantly worse firm performance during the crisis. In addition, firms in

the top decile of leverage are examined, which are more likely to be financial distress. Brown,

et al. (1992) examine the behavior of relatively well-performing firms that subsequently

experience substantial declines in operating returns during 1979 1987. They find that,

among such firms, those with high leverage cut employment and capital expenditures

significantly more than those with low leverage.

3.2.3. Other Variables

3.2.3.1. Profitability

Lots of previous papers study that financial leverage may affect cost of capital, and ultimately

it will influence firms profitability and stock prices. However, whether firm leverage and

profitability have positive relation or negative relation is ambiguous.

J ensen and Meckling (1976), Easterbrook (1984), and J ensen (1986) consider a positive

relationship between leverage and profitability. Likewise, Dann (1981) and J ames (1987)

note that leverage increasing events - such as stock repurchases or debt-for-equity exchanges

- may have higher abnormal returns while compared with the leverage decreasing events such

as issuing stock. According to the trade-off model, Drobetz and Wanzenried (2006) also

suggest more profitable firms use more debt.

Conversely, other economists have opposite opinions about their relationship. For example,

the pecking order theory suggests more profitable firms should be less leveraged because

they prefer raising capital from retained earnings first, before turning to debt, and lastly to

new equity. Sunder and Myers (1999) show the same idea with pecking order theory; they

explain the most profitable firms in many industries often have the lowest debt ratio. Titman

and Wessels (1988) observe that highly profitable firms have lower levels of leverage than

less profitable firms based on their earnings before seeking outside capital. In addition, stock

prices reflect how the firm performs. Firms tend to issue equity rather than debt when their

stock price increases, so that their leverage levels stay lower than firms using debt. According

to Wald (1999), profitability, which is the most significant determinant of firms financial

leverage, negatively affects the debt to asset ratios in the heteroskedastic tobit regression

model. Sheel (1994) also supports the negative relationship between debt-to-asset ratio and

non-debt tax shield and between firms leverage behaviour and its past profitability. Myers

(1993) and Strebulaev (2007) show that after a firm experiences, an increase in profitability

will lead to lower book and market leverage if the firm chooses not to either buy back shares

or issue debt.

In addition, the relationship between crisis and profitability are also illustrated by many

papers. Bris and Koskinen (2001) consider decreasing in firm profitability is an early warning

of currency problems. Their model implies small, export-oriented countries that suffer

depreciations display declining profitability prior to the depreciation. In the research of Bris

et al. (2004), they examine this relation by using two measures of profitability (EBIT and

total revenues, and return on capital employed), and they find significant declines in

profitability under both measures and in the three regions (Europe, Asia and Latin America)

under consideration for their crisis sample in the two years preceding the crisis.

3.2.3.2. Growth Opportunity

Fatmasari (2008) suggests that based on the theory of J ensen and Meckling, the debt policy

may lead to agency costs, which come from the agency conflict between shareholders and

bondholders. This condition shows that, in companies with high investment opportunity, the

use of debt will become expensive and cause a high cost of debt. Hence, the company will get

a positive NPV projects and lose the opportunities to grow. To avoid the problems on the cost

of debt, companies with high investment opportunity will choose to use the loan in small

amounts, or to use internal funds as an alternative funding. As a result, the relationship

between the leverage and investment opportunity will be negative.

Goyal et al. (2002) find when growth opportunities of firms decline, these firms increase their

use of debt financing, they show negative relation between leverage and growth opportunities.

Same with Goyal et al., Mayers (1997) states firms with valuable growth opportunities would

never issue risky debt and the firm financed with risky debt will refuse valuable investment

opportunities, which could make a positive net contribution to the market value of the firm.

In the contrary, some authors also issued papers with different opinion, they suggested the

relationship between growth opportunity and firm leverage is positive.

Billett et al. (2007) conclude that although growth opportunities directly affect the leverage in

a negative direction, there is a positive relationship between leverage and growth

opportunities because of covenant protection. Debt covenants may attenuate the negative

effect of growth opportunities on leverage by mitigating the agency costs of debt for high

growth firms. Chen and Zhao (2006) also document a non-monotonic and positive

relationship between market-to-book ratio (also regarded as growth opportunities) and

leverage. Firms with higher market-to-book ratios are on average more profitable and face

lower borrowing costs, while firms with low growth opportunities retire more debt.

Pandey (2001) suggests firms that enjoy rapid growth in sales need to expand their fixed

assets. Firms with high growth (the proxy for sales growth is growth opportunities) may have

greater future need for fund and tend to retain more earnings. Pandey considers increasing in

retained earnings of high growth firms to issuance of more debt, so as to maintain the target

debt ratio. Thus, the positive relationship between debt ratio and growth is expected based on

this kind of argument. By using pecking order theory theory, Pandey also derives the same

relationship, suggests growth causes firms to shift financing from new equity to debt, as they

need more funds to reduce the agency problem.

Researchers also use other proxy for growth opportunity, and prove if they have relation with

leverage. For example, Titman and Wessels (1988) propose a negative relationship between

leverage, research and development expense (R&D), the R&D expenses always regarded as a

proxy for growth opportunities. They regard growth opportunities as capital assets that add

value to a firm but cannot be collateralized and do not generate current taxable income.

Hence, the growth opportunities of such nature are likely to lower the debt levels.

3.2.3.3. Firm Size

Firm size has become such a routine to use as a control variable in researching firm leverage;

lots of literatures have illustrated their relations.

Warner (1977) and Ang et al. (1982) argue the bankruptcy costs associated with carrying debt

tend to decline as firms become larger, and therefore large firms carry more debt. Rajan and

Zingales (1995) explain the relation by using information asymmetries between small and

large firms; large companies have smaller information asymmetries so that they have easier

access to the market of debt finance. Hence, at least when compared to internally generated

funds, issuance costs of debt financing decrease, so that this mode of financing becomes more

attractive. Rajan and Zingales show international evidence suggest that in most, though not

all, countries leverage is also cross-sectionally positively related to size.

Similarly, Kurshev and Strebulaev (2005) also offer evidence from firms in US and even the

international to suggest that large firms tend to have higher leverage ratios than small firms.

Large firms always have cheaper access to outside financing per each dollar borrowed, which

means larger firms are more likely to diversify their financing sources. In addition, they

suggested that size may also be a proxy for the probability of default; large firms are more

difficult to fail and liquidate, or, once the firm finds itself in distress, for recovery rate. Or it

can be a proxy for the volatility of firm assets, for small firms are more likely to be growing

firms in rapidly developing and thus intrinsically volatile industries.

Titman and Wessels (1988) note that issuing equity is relatively much more costly for small

firms as compared to the costs for large ones, small firms may be more leveraged than large

companies. Furthermore to reduce issuance costs even more, small firms may prefer to

borrow short term (through bank loans) rather than issue long term debt.

These authors also give some evidence that the relations between firm leverage and size are

negative or even no relations in some areas. For example, Rajan and Zingales (1995) find a

positive relationship for the US, UK, J apan and Canada. However, they report no effect for

France while the impact for Germany is negative. Other authors like Titman and Wessels

(1988) find no relationship for the US. For Belgium, Deloof and Verschueren (1998) report a

positive relationship between size and leverage, while looking separately at short term debt,

this study does not find a relationship about size.

3.2.3.4. Assets Tangibility

J ensen and Meckling (1976) suggest that as firms use more fixed assets, the cost of financing

with debt declines and firms therefore use more leverage. This argument is consistent with

the trade-off model. Besides, Campello and Giambona (2010) issue a paper that examine the

impact of asset tangibility on capital structure by exploiting variation in the supply and

demand for different types of corporate assets. Assets that are less firm specific allow for

higher debt capacity. In addition, assets that respond to supply and demand forces in their

secondary markets are likely to be more re-deployable. Using these insights, their measure of

asset tangibility includes plant, property and equipment.

Similarly, Titman, and Wessels (1988) note that bondholders monitor highly-levered firms

more closely and that the monitoring costs for firms with less collateral tend to be higher.

Consequently in highly-levered firms with fewer fixed assets there tend to be higher

monitoring costs and therefore fewer resources available for managers to waste on perquisites.

As a result, they consider a positive relationship between tangibility (measured as the ratio of

property, plant, and equipment to total assets) and firm leverage. The same viewpoint also

proved by Rajan and Zingales (1995). This is largely explained by the fact that tangible assets

can be pledged as collateral to lenders and thus allow companies to raise debt.

Negative relationship has been reported between leverage and fixed assets in small and

medium firms (Daskalakis and Psillaki, 2009) and in less developed economies (J oever,

2006). By using data from New Zealand firms with period from 1984 to 2009, Smith, et al.

(2010) also show that for both book leverage and market leverage, the tangibility variable is

significant at the one per cent level and has a negative sign, which is consistent with Titman

and Wessels (1988). The higher monitoring costs associated with having fewer fixed assets

may encourage firms to use more debt.

4. Data

4.1. Collection of Data

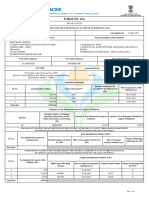

[INSERT TABLE I]

I have chosen fourteen countries (in fact, there are fifteen markets, because the market of

China and Hong Kong is separated) which around Pacific Rim. The time period of my data is

from 1985 to 2011. Among them, there are four times crises, so I divide them into three parts.

After sorting them out by checking whether the firm has full data information for the period I

need, I get 531 firms in Crisis I (1994 2001), 1564 firms in Crisis II (1994 2001), and

4598 firms in Crisis III (2004 2011). All data in my research come from Datastream.

Besides, all bank corporations are excluded by this kind of resource.

4.2. Determinants of Variables

Exchange rate

Monthly exchange rate for the fifteen markets in my research peg to the U.S. dollar.

Return on Market

The price of market comes from the Datastream world index, the calculation is Return on

Market =(market price of time t - market price of time t-1) / market price of time t.

Firm Leverage

As the dependent variable in my research, I test the relation between leverage and crisis not

only in book value, but also in market value.

My proxy for book value is the total debt divided by the sum of book value of equity and

total debt. Total debt is defined as the sum of short term debt, current portion of long term

debt, and long term debt. Book value of equity is defined as the total of minority interest,

preferred stock, and common equity.

For market value of leverage, I replace book value of equity by the market value of equity.

Market value of equity is calculated as the product of the number of shares on issue and the

market price of the firms share as the firms balance date.

Crisis

For illustrating the relation between leverage and crisis, I set a dummy variable for crisis year.

According to the timeline of the 1987 Black Monday, the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, the

Subprime Crisis, and the European Sovereign-debt Crisis, I separate the 26 years into three

parts. Among them, the years 1987 to 1988, 1997 to 1998, and 2007 to 2011 are set to one;

the rest of years are set to zero.

Profitability

The proxy for profitability is earnings before interest and tax (EBIT) divided by the book

value of assets.

Growth Opportunities

In my research, I calculate the growth opportunities as market value of equity divided by

book value of equity.

Firm Size

My proxy for firm size is the natural log of the book value of the firms assets.

Assets Tangibility

The tangibility is calculated as the book value of the firms plant and vehicles divided by the

book value of the firms assets.

Financial Fragility (Current ratio)

High leverage reduces a firms ability to finance growth through a liquidity effect. Myers

(1977) shows that, in extreme cases, a firms debt overhang can be large enough to prevent it

from raising funds to finance positive net present value projects. Financial fragility can be

also seems as current ratio, it used to test whether firms have enough resources to pay their debts.

The proxy for current ratio is current assets divided by current liabilities.

Industry Classification

I used the industry definition in Datastream, which classify all firms into ten groups. Ten

groups include Oil & Gas, Basic Materials, Industrials, Consumer Goods, Health Care,

Consumer Services, Telecommunications, Utilities, Financials and Technology.

4.3. Correlation between variables

[INSERT TABLE III]

This table is about the correlation among all explanatory variables, the correlation between 0

to 0.2 means very weak that can be negligible, and 0.2 to 0.4 means weak or low correlation.

Except to the correlation between tangibility and growth opportunities, all remaining

correlations are lower than 0.2 that can be ignored. For tangibility and growth, the correlation

is 0.39, which is lower than 0.4 and seems weak or low as well. As a result, the correlation

among all explanatory variables in my research is very weak; it means their correlations

cannot affect the final result of my research.

5. Methodology

5.1. Exchange rate exposure

To divide firms into two groups by using the relation between their stock returns and

exchange rate changes, the research follows El-Masry (2003).

Test 1

,

= +

1

+

2

+

,

,

is the stock return of firm i in country j

is the monthly change in the exchange rate in country j

is the stock return of market

By using this model, I can separate all firms into two groups. One group called positive

exposure group, firms in this group has positive beta of stock return that respect to the

monthly change in the exchange rate, which means it benefit from currency depreciation.

Another group can be regarded as negative exposure group, firms in this group has negative

beta of exchange rate that relative to individual stock return, these firms are suffer from

currency depreciation. Like Bris et al. (2004), the two groups that depend on its exposure to

exchange rate are: firm that benefit from currency depreciations and firms that suffer from

depreciations.

5.2. Firm Leverage

To test the relation between leverage and crisis, leverage is set as dependent variable, crisis year as

dummy variable, and five other control variables in both country-level and industry-level, the

regression model is:

Test 2

=

0

+

0

+

1

+

2

+

3

+

4

+

5

+

In order to test the relationship between firm leverage and crisis more accurate, firms are

sorted not only based on their exchange exposure group, but also industry classification. As

follows:

Step 1: Divide firms into three parts as C1 (Crisis I, 1985 1991), C2 (Crisis II, 1994 2001),

C3 (Crisis III, 2004 2011) based on three crises years

Step 2: According to the

1

of stock return in test 1, set C1, C2, and C3 into two groups

positive exposure firms (such as C1_(+), etc.) and negative exposure firms (such as C1_(-),

etc.)

Step 3: On the basis of the industry classification, C1_(+) can be sort into C1_(+)_O1 (Oil &

Gas), C1_(+)_BM (Basic Materials),, etc. The same for C2 and C3

5.3. Hypothesis

According to previous literatures, I make two hypotheses in this paper, as follows:

Hypothesis 1: In positive exposure group, firms increase their equity-level in crises period;

as a result, they decrease their debt-level. Debt ratio change is a long term change, so the

decreasing debt ratio for a firm is affected by lowering market value of itself.

Hypothesis 2: In negative exposure group, firms may suffer from crisis, it leads two kinds of

result for debt ratio: 1) a firm with high profitability can help to maintain its reputation and

relationships in crises, it may increase debt to overcome financial distress; 2) in contrary,

unhealthy firm issue conditioner shares to overcome financial distress, which decrease debt

ratio.

6. Empirical results and discussions

6.1. Exchange rate exposure

[INSERT TABLE IV]

Table IV shows for each country the average exchange rate, which is the size-weighted

average of the exchange rate betas that calculated for the firms in a particular country. Firms

are divided into two groups negative exposure group and positive exposure group

depending on their exposure to exchange rate movements.

Australia, Thailand and Russia are significant at 10% level or better for both negative and

positive exposure groups. Six countries - New Zealand, Mexico, Chile, Malaysia, Philippines

and Singapore - are significant at 10% or better level for both groups in three crises periods

except the negative exposure group in Crisis II (1994 2001). All East Asia countries are not

so significant: in J apan, all positive exchange betas are significant at 10% level or better, but

negative exchange betas are insignificant, this is consistent with Hamao (1988), and Brown

and Otsuki (1990), they mixed results with respect to the pricing of the exchange risk factor

in J apan using different testing procedures and sample periods; both China and South Korea

are significant at 5% and 10% level respectively only in positive exposure group in Crisis III

(2004 - 2011); Hong Kong market is significant at 5% and 10% level separately for its

negative exposure group and positive exposure group only in Crisis II (1994 2001). In

addition, Colombia only significant at 10% level of negative exchange rate beta in Crisis II;

for Peru, the 5% level significant beta is in negative exposure group in Crisis III.

Rest of them are insignificant. Bris et al. (2004) suggest exporting firms may have an

insignificant exchange rate beta if they hedge their currency exposure or if that have

borrowed in foreign currencies.

Like I have illustrated in methodology part, the positive exposure group includes firms that

may benefit from currency depreciations; and the negative exposure group includes firms that

may suffer from currency depreciations. Because of their different reaction of currency

depreciations, they may have different reaction that relate to the change of debt-to-value ratio

during crises. Relatively speaking, the number of firms that classified to positive exchange

exposure group is larger than that of negative exchange exposure group. In Crisis II (1994

2001), results of negative exposure group are more significant than positive groups; on the

contrary, positive exposure group is more significant than negative group in Crisis III (2004 -

2011).

6.2. Firm Leverage in Crises

[INSERT TABLE V]

Table V shows betas of crises year relative to both book value and market value of leverage

on country level. Crisis year is calculated as dummy variable that equal to one while the year

is affected by crises, otherwise, it is zero. Leverage is calculated as the debt-to-value ratio.

Overall, in Crisis I (1985 1991), the positive exposure group shows significant results at 1%

for both book value of leverage and market value of leverage. However, in Crisis II (1994

2001) and Crisis III (2004 -2011), only market value beta of crisis year is significant at 1%

level for two groups negative and positive.

During the First Crisis period from 1985 to 1991, J apan is the only country with significant

results at 1% level for both book and market value leverage in negative and positive exposure

groups, all results show negative relation between crisis year and leverage. It means during

Crisis I, firms in J apan have changed their debt-level.

For the negative exposure group in Crisis II (1994 2001), three countries in Southeast Asia

show significant result at 1 % level in their market leverage. For the positive exposure group

in this crisis, Peru and Thailand have significant results at 1% level and Hong Kong has

significant result at 10% level, all these results are in market leverage; only Chinese book

leverage shows significant result at 1% level.

Crisis III includes two crises, the Subprime Crisis and European Sovereign-debt Crisis, the

time period is from 2004 to 2011. The result seems better than others. In the group of

negative exposure, book leverage is significant at 10% level for South Korea and Malaysia,

and significant at 1% level for Philippines and Russia; market leverage is significant at 10%

for South Korea and Thailand, and significant at 1% for other five countries and one market

(New Zealand, Chile, China, Philippines, Russia and Hong Kong), others like South Korea

and Thailand are only significant at 10% level. In the group of positive exposure, only two

countries have significant results with book leverage, Peru is significant at 1% level, and

South Korea is significant at 5% level; all Oceania countries (Australia and New Zealand),

China and J apan are significant at 1% level with market leverage and Philippine is significant

at 5% level.

Table V is the overall of results on country level, most of them are significant at market value

of leverage, but insignificant at book value of leverage. According to this phenomenon, there

exists two explanations, one is the market value of leverage react quicker than book value of

leverage, however, the period I chose is seven to eight years, it is long enough for the change

of book value of leverage; so the second reason shows higher probability, which is the change

of market leverage is based on change of market value of their firms, not the change of debt-

to-value ratios. For better explaining the relation between crises and leverage, I sort all firms

into ten industries. The result displays in Table VI.

[INSERT TABLE VI]

Table VI shows betas of crises years relative to both book leverage and market leverage on

industry-level. As a whole, there are three industries, Industrials, Consumer Goods and

Technology, show the most significant results while comparing with others.

In the crisis I (1985 1991), the industry Consumer Goods resulting in 1% significant level,

for both negative and positive exposure group. Oil & Gas, Basic Materials, and Industrials

are only different from zero at 1% level in positive exposure group, for both book leverage

and market leverage. Their relations are negative.

During 1994 to 2001, Crisis II, Consumer Goods is also affected by crisis, but the result is

only significant at 5% level or better in negative exposure group. Others like Industrials,

Financials, and Technology have the results that significant for both negative group and

positive group, but only for the result that relative to market value of leverage.

The same result also appears in Crisis III (2004 2011), Oil & Gas, Industrials, Consumer

Goods, and Technology are all significant at 10% level or better while with market value of

leverage for both negative and positive exposure groups. Besides, Basic Materials and

Utilities have significant results in market value in negative exposure group, and Consumer

Services show significant result at 5% level in market value leverage in positive exposure

group.

For both Crisis II and Crisis III, crises years have positive relation with leverage, which

means debt-to-value increases during these two crises.

Table V and VI are overall results for firms that based on country level or industry level. It

only shows a universal result of the relation between leverage and crises. According to the

specificity for each industry in each country, I select some countries that have most

significant results in each crisis for further discussing.

[INSERT TABLE VII]

Table VII shows the result of each industry for both negative and positive exposure groups in

J apan during the period from 1985 to 1991 (Crisis I). From this table, we can see clearly that,

during 1985 to 1991, leverage of firms are affected by the crisis called 1987 Black Monday;

especially in three industries (Basic Materials, Industrials, and Consumer Goods), all results

are significant at 10% level or better. The positive exposure group of both Oil & Gas and

Consumer Goods are significant at 5% level for their market value of book value. All

relations between them are negative. These results show that, during 1985 to 1991, no matter

negative exposure group or positive group of Basic Materials, Industrials and Consumer

Goods decrease their debt; Oil & Gas and Consumer Services decline their debt level only in

positive exposure group.

However, negative exposure group of Consumer Services only has significant result in

market value of leverage; it indicates that the reason for the change of debt-to-value ratio is

not because of the debt level.

[INSERT TABLE VIII]

As I have illustrated in the part of Background, the Crisis II-Asian Crisis starts in Thailand.

Table VIII shows the results of Thailand for the period during 1994 to 2001. In this table,

Basic Materials and Consumer Goods are significant at 10% level or better for both two

groups, Oil & Gas and Telecommunications are significant at 10% level or better only in

positive exposure group because of the limitation data resource of Datastream. Another group

that shows significant result for book leverage and market leverage is positive exposure

group of Technology. This kind of results illustrate their leverage change is relate to the debt

level change. Furthermore, all these significant results show positive relations between crisis

year and leverage, which means during the crisis, firms increase their debt-level.

Others like both two groups in Industrials and Financials, negative exposure group in Health

Care, Consumer Services, and Technology, show significant result at 1% level, the

phenomenon offers that the change of debt-to-value ratio does not relate to debt level change.

The remaining groups in this table show insignificant result, which means the crisis have no

effect on them.

[INSERT TABLE IX]

Table IX shows results of four markets, Chile, Hong Kong, South Korea, and Russia, which

have relatively more significant t-value of dummy variable - crisis year in the negative

exposure group in Crisis III (2004 2011).

In Chile, three industries show the change of leverage is based on the change of debt level,

they are Basic Materials, Industrials and Health Care. Among them, Industrials increase their

debt level during the crisis, but other two industries decrease their debt in the crisis.

In Hong Kong, Oil & Gas and Basic Materials show significant results at 10% level or better,

it indicate they increase their debt level during the crisis. Others like Industrials, Health Care

and Utilities just significant at 5% level or better in market value of leverage, it cannot

illustrate there exists relations between debt-to-value ratios and crisis.

For South Korea, Basic Materials results show negative significant results at 1% level, and

Consumer Goods show positive result at 10% level. From results of these two groups, Basic

Materials declines their debt level, and Consumer Goods increase their debt level.

For Russia, all relations between leverage and crisis are positive. Especially for three

industries, Basic Materials, Industrials and Utilities, all of them are significant at 1% level.

[INSERT TABLE X]

Table X displays the positive exchange exposure group in crisis III; the most affected markets

are also four, which are Australia, China, Hong Kong and J apan.

In Australia, almost all industries market value of leverage have been affected, except

Telecommunications and Technology; but the effect of book value leverage only happen in

Consumer Goods, Health Care, and Utilities. As a result, industries that actually affected by

the crisis are Consumer Goods, Health Care and Utilities; the first two show positive relations,

and the last one shows the negative relation.

China has the same situation as Australia, but the industries with no effect on market value

leverage are Oil & Gas and Consumer Services; for book value of leverage, the only affected

industry is Health Care. The only industry that changes their debt level is Health Care, it

decreases its debt.

Hong Kong and J apan do not have much affection as other two. In Hong Kong, only

Consumer Services is affected for both book leverage and market leverage, others like

Consumer Goods, Utilities, Financials, and Technology are only significant at 5% level or

better in market value of leverage. However, although both book leverage and market

leverage show significant results for Health Care, the relation is inconsistent.

In J apan, three industries have been affected for both book leverage and market leverage,

which are Basic Materials, Consumer Goods, and Health Care, which means they all affected

by the crisis, and all of them increase their debt level; others like Industrials, Consumer

Services, Telecommunications, and Technology are only significant at 5% level or better in

market value of leverage.

7. Conclusion

This paper aims to illustrate the relationship between firm leverage and crises, to test whether

firms change their debt-level during crises periods in both country level and industry level.

For better explanation, firms are separated into several different groups as follows. Firstly,

based on the relation between stock price for individual firms and exchange rate, firms are

divided into two groups, one is the positive exposure group, which includes firms that benefit

from currency appreciations; and another is the negative exposure group includes firms that

suffer from currency appreciations. Then, according to the industry classification, these two

groups are sorted by ten industries for each country. Lastly, test the relationship between

leverage and crises by using model in Test 2.

In exchange rate exposure test, results are inconsistent in three crises periods. In Crisis II

(1994 2001), results of negative exposure group are more significant than positive groups;

however, Crisis III (2004 -2011) shows opposite results, positive exposure group is more

significant than negative exposure group.

For country level, in Crisis I (1985 to 1991), J apan is the only country affected by the 1987

Black Monday in my sample, especially three industries Basic Materials, Industrials and

Consumer Goods in it, all of them decrease their debt-level during the Crisis I. In the overall

results of Crisis II (1994 to 2001), no countries are actually affected by the 1997 Asian

Financial Crisis; however, after dividing them into industries, Basic Materials and Consumer

Goods show significant results for both book value of leverage and market value of leverage,

which means they increase their debt-level during the Asian Crisis. In the last two crises

periods, South Korea and Philippines show significant results in their negative exposure

group for the whole results table; after dividing into different industries, Basic Materials is

the most affected industry in negative exposure group, Consumer Goods and Health Care are

the most affected industries in positive exposure group.

For industry level, firms in Crisis I show the most significant results, such as Consumer

Goods in negative exposure group, and Oil & Gas, Basic Materials, Industrials and Consumer

Goods in positive exposure group. All of them show negative relations, which means these

firms decrease their debt-level during the crisis period. Industries in other two crises periods

show significant results only in market value of leverage, all of them are positive, which

means these change of debt-to-value ratios may base on change of market value, not the debt

itself.

According to results above, only betas of J apan in Crisis I are consistent with hypothesis 1 in

country level, both book leverage and market leverage are negative related with crisis, which

means firms in positive exposure group of J apan decrease their debt-level during Crisis I. In

industry level, Oil & Gas, Basic Materials, Industrials and Consumer Goods show consistent

results with hypothesis 1, all firms inside them decrease debt-level during Crisis I.

For negative exposure group in country level, J apan in Crisis I and Philippines in Crisis III

show consistent results with the second situation in hypothesis 2, firms may decrease debt

ratio by issuing conditioner shares to overcome financial distress; results of Russia in Crisis

III have consistent results with the first situation in hypothesis 2, firms increase their debt

ratios may be based on their high profitability before. In industry level, Consumer Goods

show consistent results with first situation in hypothesis 2 in Crisis I, and consistent with

second situation in hypothesis 2 in Crisis II.

There could be some problems in the paper: at first, because of the limitation of data resource,

the exchange rate I chose is based on the U.S. dollar, by using this kind of exchange rate, the

result may only consider the trade between the home country and the US; it cannot explain

the whole change of their exporting or importing trades. Secondly, because of the variable

total debt in Datastream is collected in yearly, I have to choose crisis year as my dummy

variable, the frequency of data is yearly; however, some crises begin at the end of year, the

better way in using dummy variable should be monthly, the month affected by the crisis is

equal to one, others are zero, it may make the results more accurate.

Tables

Table I

Country

Crisis I Crisis II Crisis III

(1985 - 1991) (1994 - 2001) (2004 - 2011)

Oceania

1 AUS 17 47 299

2 NZ 11 49

North

America

3 Mexico

31 61

South

America

4 Chile 44 96

5 Colombia

7 10

6 Peru 6 67

East Asia

7 China

36 1016

8 HK 16 80 510

9 Japan 476 944 1168

10

South

Korea

119

Southeast

Asia

11 Malaysia 11 72 438

12 Philippines

24 70

13 Thailand

206 349

14 Singapore 11 56 305

Europe

15 Russia

41

Total 531 1564 4598

Table I. Sample Description.

From 1985 to 2011, there are 26 years. I divide them into three crises periods, Crisis I is from

1985 to 1991, Crisis II is from 1994 to 2001, and Crisis III is from 2004 to 2011. This table

displays number of firms in the sample for fourteen countries (with fifteen markets, China

and Hong Kong are two markets in one China) in each crisis.

Table II

Summary Statistic

Variable Mean Median Minimum

1st

Pctl

99th Pctl Maximum Std Dev Skewness Kurtosis N

BV of Leverage 0.37 0.34 -767.92 0 1.2 508.52 5.77 -31.47 9980.63 52933

MV of Leverage 0.42 0.34 0 0 1 1 0.33 0.55 -1.01 52933

Crisis Year 0.51 1 0 0 1 1 0.5 -0.05 -2 52933

Profitability 0.17 0.07 -2093.75 -0.43 2.14 192.39 10.78 -161.4 29449.05 52933

Growth Opportunity 3.48 0.94 -4055.98 -2.17 31.96 9381.12 76.99 70.79 7381.06 52933

FirmSize 16.15 16.31 4.22 9.82 22.12 24.2 2.86 -0.15 -0.55 52933

Tangibility 0.82 0.31 0 0 4.98 1898.04 15.5 80.3 8013.84 52933

Current Ratio 1.63 1.28 -67.06 0.13 7.01 388.68 2.67 73.46 9219.55 52933

Exchange Exposure Beta 1.23 0.43 -47.07 -16.39 22.63 192.68 7.71 8.74 158.95 52933

Table II. Summary Statistic.

This table shows descriptive statistics of the leverage and explanatory variables used in the analysis. Book value of leverage is the total debt

divided by the sum of book value of equity and total debt. Market value of leverage is the total debt divided by the sum of market value of equity

and total debt. Crisis is the dummy variable that equal to one in crises years, and equal to zero in the rest. Profitability is earnings before interest

and tax divided by the book value of assets. Growth opportunity is the market value of equity divided by book value of equity. Firm size is the

natural log of the book value of the firms assets. Tangibility is the book value of the firms plant and vehicles divided by the book value of the

firms assets. Current ratio is the current assets divided by current liabilities. Exchange exposure beta is the coefficient of exchange rate while

relative to stock returns.

Table III

Crisis Profitability Growth Firm size Tangibility Current ratio

Crisis 1

Profitability -0.00426 1

Growth 0.012313 0.08700991 1

Firm size -0.07537 0.02417722 -0.022 1

Tangibility 0.009213 0.18677689 0.392808 -0.0339 1

Current ratio 0.020079 0.00498195 -0.00741 -0.03368 -0.006254 1

Table III. Correlation.

This table is about the correlation for all explanatory variables in this paper, the correlation

between 0 to 0.2 means very weak that can be negligible, and 0.2 to 0.4 means weak or low

correlation. Except to the correlation between tangibility and growth opportunities, all

remaining correlations are lower than 0.2 that can be ignored. For tangibility and growth, the

correlation is 0.39, which is lower than 0.4 and seems weak or low as well.

Table IV

Country

Crisis I (1985 -1991) Crisis II (1994 -2001) Crisis III (2004 -2011)

Negative Positive Negative Positive Negative Positive

N

Average

Exchange

Beta

N

Average

Exchange

Beta

N

Average

Exchange

Beta

N

Average

Exchange

Beta

N

Average

Exchange

Beta

N

Average

Exchange

Beta

Oceania

AUS 14 -0.5630

31 -0.5494 16 0.3883 96 -0.4940 203 0.6172

(-2.57)***

(-3.18)***

(3.10)***

(-3.14)***

(5.95)***

NZ

8 -0.3651 3 0.1532 9 -0.3054 40 0.3408

(-1.89)*

(0.75)

(-2.63)***

(4.11)***

North America

Mexico 27 -0.5227 4 0.1643 27 -0.5447 34 0.4210

(-4.52)***

(1.19)

(-2.44)**

(3.51)***

South

America

Chile 37 -0.6819 7 0.3293 48 -0.1703 48 0.1799

(-2.55)**

(1.63)

(-1.87)*

(1.88)*

Colombia

3 -0.2292 4 0.4805 4 -0.1125 6 0.2689

(-0.50)

(1.94)*

(-0.56)

(1.12)

Peru

4 -1.4564 2 4.2041 39 -0.6547 28 1.2259

(-1.08) (0.96) (-2.16)** (1.18)

East Asia

China

32 -0.2772 4 0.0610 26 -2.8578 990 5.8299

(-1.14)

(0.21)

(-1.29)

(2.35)**

HK 13 -6.0418 3 8.0523 22 -24.2893 58 46.0763 322 -9.6484 188 12.1413

(-1.16)

(1.33)

(-1.75)*

(2.27)**

(-1.47)

(1.54)

Japan 39 -0.2305 437 0.6522 169 -0.1882 775 0.4547 87 -0.1826 1081 0.7612

(-1.12)

(3.39)***

(-0.82)

(2.43)**

(-1.21)

(4.77)***

South Korea

45 -0.5785 74 0.6124

(-1.61)

(1.77)*

Southeast

Asia

Malaysia 11 2.3332 70 -2.1372 2 0.1396 213 -0.7532 225 0.8508

(2.23)**

(-5.14)***

-0.4800

(-2.22)**

(2.29)**

Philippines

18 -1.1394 6 0.2431 51 -1.1628 19 1.5253

(-4.10)***

-1.1700

(-2.46)**

(2.32)**

Thailand

114 -0.5236 92 0.5874 258 -0.9119 91 0.6053

(-2.62)***

(3.41)***

(-4.29)***

(3.30)***

Singapore

11 2.4978 51 -1.8273 5 0.5368 74 -0.7501 231 1.0679

(3.37)*** (-3.35)*** -0.9300 (-1.81)* (2.52)**

Europe

Russia

22 -0.7342 19 0.5878

(-2.43)**

(2.52)**

Total 66 -6.8353 463 0.7828 586 -1.6448 978 3.2002 1321 -2.9135 3277 2.9458

*, ** and *** indicate that the coefficient is significantly different from zero at the 0.1, 0.05 and 0.01 levels or better, respectively.

Table IV. Regression results for exchange rate exposure.

The table shows regression results for exchange rate exposure in three crises periods since 1985 to 2011. The results are based on the coefficients

of exchange rate that relative to individual stock returns, which is calculated as follows:

,

= +

1

+

2

+

,

, where

,

is the stock

return of firm i in country j,

is the monthly change in the exchange rate in country j,

is the stock return of market. Stock returns,