Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Madeja V Caro

Uploaded by

Sean GalvezOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Madeja V Caro

Uploaded by

Sean GalvezCopyright:

Available Formats

MADEJA V. CARO 1983 FACTS: In Criminal Case, DR. EVA A.

JAPZON is accused of homicide through reckless imprudence for the death of Cleto Madeja after an appendectomy. The complaining witness is the widow of the deceased, Carmen L. Madeja. The information states that: "The offended party Carmen L. Madeja reserving her right to file a separate civil action for damages." (Rollo, p. 36.) The criminal case still pending, Carmen L. Madeja sued Dr. Eva A. Japzon for damages in Civil Case No. 141 of the same court. She alleged that her husband died because of the gross negligence of Dr. Japzon. The respondent judge granted the defendant's motion to dismiss which motion invoked Section 3(a) of Rule 111 of the Rules of Court Sec. 3. Other civil actions arising from offenses. In all cases not included in the preceding section the following rules shall be observed: (a) Criminal and civil actions arising from the same offense may be instituted separately, but after the criminal action has been commenced the civil action can not be instituted until final judgment has been rendered in the criminal action. ... According to the respondent judge, "under the foregoing Sec. 3 (a), Rule 111, New Rules of Court, the instant civil action may be instituted only after final judgment has been rendered in the criminal action." (Rollo, p. 33.) The instant petition which seeks to set aside the order of the respondent judge granting the defendant's motion to dismiss Civil Case No. 141 is highly impressed with merit. Section 2, Rule 111 of the Rules of Court in relation to Article 33 of the Civil Code is the applicable provision. The two enactments are quoted hereinbelow: Sec. 2. Independent civil action. In the cases provided for in Articles 31,32, 33, 34 and 2177 of the Civil Code of the Philippines, an independent civil action entirely separate and distinct from the criminal action, may be brought by the injured party during the pendency of the criminal case, provided the right is reserved as required in the preceding section. Such civil action shall proceed independently of the criminal prosecution, and shall require only a preponderance of evidence." (Rule 111, Rules of Court.) Art. 33. In cases of defamation, fraud, and physical injuries, a civil action for damages, entirely separate and distinct from the criminal action, may be brought by the injured party. Such civil action shall proceed independently of the criminal prosecution, and shall require only a preponderance of evidence. (Civil Code,) There are at least two things about Art. 33 of the Civil Code which are worth noting, namely: 1. The civil action for damages which it allows to be instituted is ex-delicto. This is manifest from the provision which uses the expressions "criminal action" and "criminal prosecution." This conclusion is supported by the comment of the Code Commission, thus: The underlying purpose of the principle under consideration is to allow the citizen to enforce his rights in a private action brought by him, regardless of the action of the State attorney. It is not conducive to civic spirit and to individual selfreliance and initiative to habituate the citizens to depend upon the government for the vindication of their own private rights. It is true that in many of the cases referred to in the provision cited, a criminal prosecution is proper, but it should be remembered that while the State is the complainant in the criminal case, the injured individual is the one most concerned because it is he who has suffered directly. He should be permitted to demand reparation for the wrong which peculiarly affects him. (Report, p. 46.) And Tolentino says: The general rule is that when a criminal action is instituted, the civil action for recovery of civil liability arising from the offense charged is impliedly instituted with the criminal action, unless the offended party reserves his right to institute it separately; and after a criminal action has been commenced, no civil action arising from the same offense can be prosecuted. The present articles creates an exception to this rule when the offense is defamation, fraud, or physical injuries, In these cases, a civil action may be filed independently of the criminal action, even if there has been no reservation made by the injured party; the law itself in this article makes such reservation; but the claimant is not given the right to determine whether the civil action should be scheduled or suspended until the criminal action has been terminated. The result of the civil action is thus independent of the result of the civil action." (I Civil Code, p. 144 [1974.]) 2. The term "physical injuries" is used in a generic sense. It is not the crime of physical injuries defined in the Revised Penal Code. It includes not only physical injuries but consummated, frustrated and attempted homicide. The Article in question uses the words 'defamation', 'fraud' and 'physical injuries.' Defamation and fraud are used in their ordinary sense because there are no specific provisions in the Revised Penal Code using these terms as means of offenses defined therein, so that these two terms defamation and fraud must have been used not to impart to them any technical meaning in the laws of the Philippines, but in their generic sense. With this apparent circumstance in mind, it is evident that the terms 'physical injuries' could not have been used in its specific sense as a crime defined in the Revised Penal Code, for it is difficult to believe

that the Code Commission would have used terms in the same article-some in their general and another in its technical sense. In other words, the term 'physical injuries' should be understood to mean bodily injury, not the crime of physical injuries, bacause the terms used with the latter are general terms. In any case the Code Commission recommended that the civil action for physical injuries be similar to the civil action for assault and battery in American Law, and this recommendation must hove been accepted by the Legislature when it approved the article intact as recommended. If the intent has been to establish a civil action for the bodily harm received by the complainant similar to the civil action for assault and battery, as the Code Commission states, the civil action should lie whether the offense committed is that of physical injuries, or frustrated homicide, or attempted homicide, or even death," (Carandang vs. Santiago, 97 Phil. 94, 96-97 [1955].) Corpus vs. Paje, which states that reckless imprudence or criminal negligence is not included in Article 33 of the Civil Code is not authoritative. Of eleven justices only nine took part in the decision and four of them merely concurred in the result. it is apparent that the civil action against Dr. Japzon may proceed independently of the criminal action against her. the petition is hereby granted; the order dismissing Civil Case No. 141 is hereby set aside; no special pronouncement as to costs.

You might also like

- Heirs of Magdaleno Ypon v. RicaforteDocument2 pagesHeirs of Magdaleno Ypon v. RicaforteSean Galvez100% (1)

- Benny Sampilo and Honorato Salacup v. CADocument3 pagesBenny Sampilo and Honorato Salacup v. CASean GalvezNo ratings yet

- Adiong V ComelecDocument3 pagesAdiong V ComelecSean GalvezNo ratings yet

- Adiong v. ComelecDocument2 pagesAdiong v. ComelecSean GalvezNo ratings yet

- in Re - Testate Estate of The Late Gregorio VenturaDocument2 pagesin Re - Testate Estate of The Late Gregorio VenturaSean GalvezNo ratings yet

- Dela Cruz v. Dela Cruz PDFDocument3 pagesDela Cruz v. Dela Cruz PDFSean GalvezNo ratings yet

- Suntay v. SuntayDocument2 pagesSuntay v. SuntaySean GalvezNo ratings yet

- Delfin Tan v. BeneliraoDocument5 pagesDelfin Tan v. BeneliraoSean GalvezNo ratings yet

- Franiela v. BanayadDocument1 pageFraniela v. BanayadSean GalvezNo ratings yet

- In Re Palaganas v. PalaganasDocument2 pagesIn Re Palaganas v. PalaganasSean GalvezNo ratings yet

- Creser v. CADocument2 pagesCreser v. CASean GalvezNo ratings yet

- Nuguid v. Nuguid DDocument2 pagesNuguid v. Nuguid DSean GalvezNo ratings yet

- Vargas v. ChuaDocument2 pagesVargas v. ChuaSean Galvez100% (1)

- De Los Santos V MontesaDocument3 pagesDe Los Santos V MontesaSean GalvezNo ratings yet

- Samson V CabanosDocument3 pagesSamson V CabanosSean GalvezNo ratings yet

- Pascual v. CA 2003Document2 pagesPascual v. CA 2003Sean GalvezNo ratings yet

- Samson V DawayDocument3 pagesSamson V DawaySean GalvezNo ratings yet

- In The Matter For The Declaration of William GueDocument2 pagesIn The Matter For The Declaration of William GueSean GalvezNo ratings yet

- People v. GesmundoDocument3 pagesPeople v. GesmundoSean GalvezNo ratings yet

- Rubi V Prov of MindoroDocument3 pagesRubi V Prov of MindoroSean GalvezNo ratings yet

- Guzman V NuDocument3 pagesGuzman V NuSean GalvezNo ratings yet

- De Guzman V Angeles PDFDocument3 pagesDe Guzman V Angeles PDFSean GalvezNo ratings yet

- Ermita Motel Association V Mayor of ManilaDocument5 pagesErmita Motel Association V Mayor of ManilaSean GalvezNo ratings yet

- Tabuena v. SandiganabayanDocument3 pagesTabuena v. SandiganabayanSean GalvezNo ratings yet

- People V CayananDocument1 pagePeople V CayananSean GalvezNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

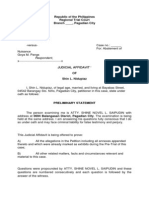

- JUDICIAL AFFidavitDocument4 pagesJUDICIAL AFFidavitXhain Psypudin100% (1)

- Baguio Midland Carrier v. CADocument12 pagesBaguio Midland Carrier v. CAKPPNo ratings yet

- Notes On Statutory ConstructionDocument12 pagesNotes On Statutory ConstructionMariel EfrenNo ratings yet

- People of The Philippines vs. Noel BartolomeDocument2 pagesPeople of The Philippines vs. Noel BartolomeAdreanne Vicxee TejonesNo ratings yet

- Bernabe Castillo Et Al v. Hon. Court of Appeals, Et AlDocument2 pagesBernabe Castillo Et Al v. Hon. Court of Appeals, Et AlRegion 6 MTCC Branch 3 Roxas City, CapizNo ratings yet

- RemDocument9 pagesRemChiefJusticeLaMzNo ratings yet

- People v. PedroDocument8 pagesPeople v. PedroRe doNo ratings yet

- Joaquin, Jr. vs. Drilon, 302 SCRA 225, G.R. No. 108946 January 28, 1999Document17 pagesJoaquin, Jr. vs. Drilon, 302 SCRA 225, G.R. No. 108946 January 28, 1999Anonymous HujGfHNo ratings yet

- Complainant: For: Other Sexual Abuse (Lascivious Conduct Under Sec. 5 (B) Art III of R.A 7610 in Relation To R.A 7369)Document10 pagesComplainant: For: Other Sexual Abuse (Lascivious Conduct Under Sec. 5 (B) Art III of R.A 7610 in Relation To R.A 7369)Ric SaysonNo ratings yet

- Case Digests Annulment PDFDocument9 pagesCase Digests Annulment PDFLaurice PocaisNo ratings yet

- SMC Vs KalaloDocument2 pagesSMC Vs KalaloElaine Atienza-Illescas100% (1)

- VOL. 255, MARCH 29, 1996 397: Yonaha vs. Court of AppealsDocument8 pagesVOL. 255, MARCH 29, 1996 397: Yonaha vs. Court of AppealsJM DzoNo ratings yet

- United States v. William J. Armantrout, 411 F.2d 60, 2d Cir. (1969)Document8 pagesUnited States v. William J. Armantrout, 411 F.2d 60, 2d Cir. (1969)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Former Boca Raton Police Officer Accuses Department of Racial DiscriminationDocument14 pagesFormer Boca Raton Police Officer Accuses Department of Racial DiscriminationAnonymous DP0nOtNo ratings yet

- Periquet vs. NLRCDocument3 pagesPeriquet vs. NLRCTiffNo ratings yet

- People v. SaylamDocument4 pagesPeople v. Saylamyanyan yuNo ratings yet

- Feliciano Vs LozadaDocument4 pagesFeliciano Vs LozadajwualferosNo ratings yet

- Oca v. Lerma PonenciaDocument5 pagesOca v. Lerma Ponenciajimmyfunk56No ratings yet

- Usa Vs GuintoDocument3 pagesUsa Vs GuintoMaria Cherrylen Castor QuijadaNo ratings yet

- Application For Setting Aside Ex Parte - Alina Syed Vs Faisal Nawaz Khan 22-02-2012Document4 pagesApplication For Setting Aside Ex Parte - Alina Syed Vs Faisal Nawaz Khan 22-02-2012hearthacker_302No ratings yet

- Bar Outline 2012 RemediesDocument3 pagesBar Outline 2012 RemediesJohn Carelli100% (2)

- Parinas Vs PaguintoDocument2 pagesParinas Vs PaguintoEarnswell Pacina Tan100% (4)

- Southern District of Florida Local Rules (April 2002)Document176 pagesSouthern District of Florida Local Rules (April 2002)FloridaLegalBlogNo ratings yet

- People Vs GozoDocument2 pagesPeople Vs GozoTeresa Cardinoza100% (1)

- Eviction - Sample StipulationDocument4 pagesEviction - Sample StipulationRajeev MadnawatNo ratings yet

- Sup CourtDocument26 pagesSup CourtJeremy TurnageNo ratings yet

- Villar v. NLRC (2000)Document4 pagesVillar v. NLRC (2000)Zan BillonesNo ratings yet

- Legal Memo - in Pari DelictoDocument4 pagesLegal Memo - in Pari DelictorubbtunaNo ratings yet

- Ashley Adams v. Eric Selhorst, Et QL, 3rd Cir. (2011)Document12 pagesAshley Adams v. Eric Selhorst, Et QL, 3rd Cir. (2011)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Realino V VillamorDocument2 pagesRealino V VillamorAnonymous KZEIDzYrONo ratings yet