Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Law 1

Uploaded by

Jay RuizOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Law 1

Uploaded by

Jay RuizCopyright:

Available Formats

Facts: The petitioner invokes the constitutionally protected right to life and l iberty guaranteed by the due process

clause, alleging that no prima facie case h as been established to warrant the filing of an information for subversion again st him. Petitioner asks the Court to prohibit and prevent the respondents from u sing the iron arm of the law to harass, oppress, and persecute him, a member of the democratic opposition in the Philippines. The case roots backs to the rash of bombings which occurred in the Metro Manila area in the months of August, September and October of 1980. Victor Burns Lovely , Jr, one of the victims of the bombing, implicated petitioner Salonga as one of those responsible. On December 10, 1980, the Judge Advocate General sent the petitioner a Notice of Preliminary Investigation in People v. Benigno Aquino, Jr., et al. (which include d petitioner as a co-accused), stating that the preliminary investigation of the above-entitled case has been set at 2:30 o clock p.m. on December 12, 1980? and th at petitioner was given ten (10) days from receipt of the charge sheet and the s upporting evidence within which to file his counter-evidence. The petitioner sta tes that up to the time martial law was lifted on January 17, 1981, and despite assurance to the contrary, he has not received any copies of the charges against him nor any copies of the so-called supporting evidence. The counsel for Salonga was furnished a copy of an amended complaint signed by G en. Prospero Olivas, dated 12 March 1981, charging Salonga, along with 39 other accused with the violation of RA 1700, as amended by PD 885, BP 31 and PD 1736. On 15 October 1981, the counsel for Salonga filed a motion to dismiss the charge s against Salonga for failure of the prosecution to establish a prima facie case against him. On 2 December 1981, Judge Ernani Cruz Pano (Presiding Judge of the Court of First Instance of Rizal, Branch XVIII, Quezon City) denied the motion. On 4 January 1982, he (Pano) issued a resolution ordering the filing of an info rmation for violation of the Revised Anti-Subversion Act, as amended, against 40 people, including Salonga. The resolutions of the said judge dated 2 December 1 981 and 4 January 1982 are the subject of the present petition for certiorari. I t is the contention of Salonga that no prima facie case has been established by the prosecution to justify the filing of an information against him. He states t hat to sanction his further prosecution despite the lack of evidence against him would be to admit that no rule of law exists in the Philippines today. Issues: 1. Whether the above case still falls under an actual case 2. Whether the above case dropped by the lower court still deserves a decision f rom the Supreme Court Held: 1. No. The Court had already deliberated on this case, a consensus on the Court s judgment had been arrived at, and a draft ponencia was circulating for co ncurrences and separate opinions, if any, when on January 18, 1985, respondent J udge Rodolfo Ortiz granted the motion of respondent City Fiscal Sergio Apostol t o drop the subversion case against the petitioner. Pursuant to instructions of t he Minister of Justice, the prosecution restudied its evidence and decided to se ek the exclusion of petitioner Jovito Salonga as one of the accused in the infor mation filed under the questioned resolution. The court is constrained by this action of the prosecution and the respondent Ju dge to withdraw the draft ponencia from circulating for concurrences and signatu res and to place it once again in the Court s crowded agenda for further deliberat ions. Insofar as the absence of a prima facie case to warrant the filing of subversion charges is concerned, this decision has been rendered moot and academic by the action of the prosecution. 2. Yes. Despite the SC s dismissal of the petition due to the case s moot and academ ic nature, it has on several occasions rendered elaborate decisions in similar c ases where mootness was clearly apparent. The Court also has the duty to formulate guiding and controlling constitutional principles, precepts, doctrines, or rules. It has the symbolic function of educa ting bench and bar on the extent of protection given by constitutional guarantee s. In dela Camara vs Enage (41 SCRA 1), the court ruled that:

The fact that the case is moot and academic should not preclude this Tribunal fro m setting forth in language clear and unmistakable, the obligation of fidelity o n the part of lower court judges to the unequivocal command of the Constitution that excessive bail shall not be required. In Gonzales v. Marcos (65 SCRA 624) whether or not the Cultural Center of the Ph ilippines could validly be created through an executive order was mooted by Pres idential Decree No. 15, the Center s new charter pursuant to the President s legisla tive powers under martial law. Nevertheless, the Court discussed the constitutio nal mandate on the preservation and development of Filipino culture for national Identity. (Article XV, Section 9, Paragraph 2 of the Constitution). In the habeas corpus case of Aquino, Jr., v. Enrile, 59 SCRA 183), the fact that the petition was moot and academic did not prevent this Court in the exercise o f its symbolic function from promulgating one of the most voluminous decisions e ver printed in the Reports.

You might also like

- E 342Document2 pagesE 342Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- E 342Document2 pagesE 342Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- Title ElevenDocument2 pagesTitle ElevenJay RuizNo ratings yet

- 1111Document1 page1111Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- 111111Document1 page111111Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- 123Document1 page123Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- 111111Document1 page111111Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- E 342Document2 pagesE 342Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- 111111Document1 page111111Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- 111111Document1 page111111Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- 1Document1 page1Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- LegetDocument1 pageLegetJay RuizNo ratings yet

- 123Document2 pages123Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- 2222Document2 pages2222Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- 123Document1 page123Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- 123Document1 page123Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- 123Document1 page123Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- 123Document1 page123Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- 123Document1 page123Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- Suggested Answers in Criminal Law Bar ExamsDocument88 pagesSuggested Answers in Criminal Law Bar ExamsRoni Tapeño75% (8)

- Advocates of Til vs. BSPDocument3 pagesAdvocates of Til vs. BSPIrene RamiloNo ratings yet

- Legal MedicineDocument12 pagesLegal MedicineJay RuizNo ratings yet

- Hon. Patricia A. Sto - Tomas, Rosalinda Baldoz and Lucita Lazo, PetitionersDocument9 pagesHon. Patricia A. Sto - Tomas, Rosalinda Baldoz and Lucita Lazo, PetitionersJay RuizNo ratings yet

- 12213123Document12 pages12213123Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- Atong Paglaum, Inc. vs. Commission On ElectionsDocument143 pagesAtong Paglaum, Inc. vs. Commission On ElectionsJay RuizNo ratings yet

- Law 1Document1 pageLaw 1Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- Lambino v. ComelecDocument3 pagesLambino v. ComelecRm GalvezNo ratings yet

- Ernesto Hebron, ComplainantDocument6 pagesErnesto Hebron, ComplainantJay RuizNo ratings yet

- Law 1Document2 pagesLaw 1Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- Law 1Document3 pagesLaw 1Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Admission FormDocument2 pagesAdmission FormShakil AhmedNo ratings yet

- Food Corporation of India: Financial Statement Analysis OFDocument15 pagesFood Corporation of India: Financial Statement Analysis OFMalay Kumar PatraNo ratings yet

- RA No. 8551Document18 pagesRA No. 8551trishahaNo ratings yet

- Internal Revenue Code of 1939Document507 pagesInternal Revenue Code of 1939fredlox100% (16)

- Curriculum ViteaDocument7 pagesCurriculum ViteabissauNo ratings yet

- Chamber Registration PakistanDocument23 pagesChamber Registration PakistanNida Sweet67% (3)

- Non Refoulement PDFDocument11 pagesNon Refoulement PDFM. Hasanat ParvezNo ratings yet

- Ang Bayong Bayani vs. COMELECDocument49 pagesAng Bayong Bayani vs. COMELECCMLNo ratings yet

- History of 9-11Document140 pagesHistory of 9-11April ShowersNo ratings yet

- Veterans Services Guide in PennsylvaniaDocument2 pagesVeterans Services Guide in PennsylvaniaJesse WhiteNo ratings yet

- Visual Anatomy Ansd Physiology Lab Manual Pig Version 2nd Edition Sarikas Test BankDocument36 pagesVisual Anatomy Ansd Physiology Lab Manual Pig Version 2nd Edition Sarikas Test Bankartisticvinosezk57100% (26)

- Philippines Downplays Sultan Heirs' Sabah Claims As Private'Document7 pagesPhilippines Downplays Sultan Heirs' Sabah Claims As Private'ay mieNo ratings yet

- Origins of World War Two: International Relations ThemeDocument31 pagesOrigins of World War Two: International Relations ThemeHUSSAIN SHAHNo ratings yet

- Toda MembersDocument29 pagesToda MembersArnel GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Defeated Velvet Revolution - An Expose by Syed Jawad Naqvi About The 2006 Disputed Elections in Iran (MUST READ)Document27 pagesDefeated Velvet Revolution - An Expose by Syed Jawad Naqvi About The 2006 Disputed Elections in Iran (MUST READ)MikPiscesNo ratings yet

- DepEd Form 137-E RecordsDocument3 pagesDepEd Form 137-E RecordsJeje AngelesNo ratings yet

- Administrative Law and Its ScopeDocument3 pagesAdministrative Law and Its ScopeKashif MehmoodNo ratings yet

- Anti ATM Sangla ExplanatoryDocument2 pagesAnti ATM Sangla ExplanatoryCy ValenzuelaNo ratings yet

- Filipino: Ikalawang Markahan-Modyul 14Document20 pagesFilipino: Ikalawang Markahan-Modyul 14Libert Moore Omambat Betita100% (4)

- 1 CorpsDocument206 pages1 Corpssameera prasathNo ratings yet

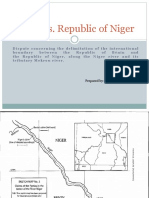

- Benin V NigerDocument9 pagesBenin V NigerRonika ThapaNo ratings yet

- Membership in KatipunanDocument2 pagesMembership in KatipunanBernadeth Liloan100% (1)

- Sri Lankan Humanitarian Operation Factual Analysis (WWW - Adaderana.lk)Document170 pagesSri Lankan Humanitarian Operation Factual Analysis (WWW - Adaderana.lk)Ada Derana100% (2)

- Constitution of the Kingdom of BhutanDocument75 pagesConstitution of the Kingdom of Bhutanktobgay6821No ratings yet

- Tajikistan - Russia Relations in Historical PerspectiveDocument16 pagesTajikistan - Russia Relations in Historical PerspectiveAnonymous CwJeBCAXp100% (1)

- Consti2 Finals CasesDocument75 pagesConsti2 Finals CasesStephanie Rose MarcelinoNo ratings yet

- Election CasesDocument22 pagesElection Caseseg_gemNo ratings yet

- Indian Constitution Question Bank For SEEDocument31 pagesIndian Constitution Question Bank For SEEhrushithar27No ratings yet

- Indian Constitution: Time: 3 Hours. Maximum Marks 100. Part - A. Attempt Any Two Questions (2 20 40)Document6 pagesIndian Constitution: Time: 3 Hours. Maximum Marks 100. Part - A. Attempt Any Two Questions (2 20 40)Obalesh VnrNo ratings yet

- Beyond Beyond Policy Analysis: Emergent Policy and The Complexity of GovernmentDocument7 pagesBeyond Beyond Policy Analysis: Emergent Policy and The Complexity of GovernmentPraise NehumambiNo ratings yet