Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A View of Whole Novel Study From Start To Finish (Excerpt From Whole Novels For The Whole Class)

Uploaded by

Jossey-Bass EducationOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A View of Whole Novel Study From Start To Finish (Excerpt From Whole Novels For The Whole Class)

Uploaded by

Jossey-Bass EducationCopyright:

Available Formats

&

Whole Novels for the Whole Class

&

PARTS OF THE WHOLE

A View of Whole Novel Study from Start to Finish

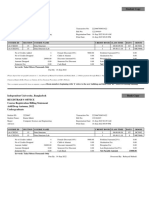

When I describe the concept of a whole novel study and the discussions that are at the center of it, one of the most pressing questions I hear from teachers is, What do you do in class while students are reading the book? I describe the various layers of work that happen along the way in Part 2 of the book, but here is an overview of the progression of a whole novel study from start to nish. Each one is a little bit different, so this serves a general summary of the ow of a single novel study. This calendar in the table is for a novel of 210 pages. Students are assigned to read fteen pages ve days a week. The items on the calendar are explained briey below.

Example of Daily Activities during a Whole Novel Study

Monday

Week Prologue 1

Tuesday

Wednesday

Thursday

Whole class check-in and reading

Friday

Introduce seeker books; Partner reading and peer feedback on notes Reading time and supplemental text/lm Books due! Discussions begin

Ritual launch Minilesson on sticky and reading notes and reading time

Week Reading time 2 and group miniproject Week Reading 3 time and discussion of supplemental text Week Discussions 4 and creative writing

Reading time Whole class check-in and group and partner or miniproject independent reading Reading time Dramatizing scenes and creative writing

Reading time and supplemental text/lm Reading day

Discussions and creative writing

Discussions and creative writing

In-class literary Creative writing essay writing share day

102

Parts of the Whole

PROLOGUE

Sometimes before launching the novel, I open with an experience that provides some context for the whole novel study were about to begin. For example, before reading Sandra Cisneross House on Mango Street, a study in which we focus on the element of setting, I read the vividly descriptive beginning of Ray Bradburys Martian Chronicles and have students write creative descriptions of real or imagined settings. Before Robert Cormiers The Chocolate War, we read and discuss an article about banned books to set students up to read the frequently banned novel and to connect to the themes of oppression and silencing in the story itself. I dont give away the connections between the prologue and the novel because I want to create opportunities for students to discover these connections.

RITUAL LAUNCH

Every whole novel study begins with a ritual launch, originally created by Noah Rubin, a former student of Madeleine Ray at Bank Street. The ritual consists of passing out to each student a gallon-size ziplock plastic bag containing everything the students will need on their reading journey and sending them off to begin. The baggie contains a copy of the book, a reading schedule, a letter Ive written to students introducing the novel and expectations for the study, sticky notes, and a bookmark or other treat. I pass out the book baggie, and we read the letter together and look at the schedule and guidelines for the study. Then I send the students to begin reading. I describe the preparation and launch in detail in Chapter 6.

READING TIME

Once Ive launched the study, I devote lots of time to reading during class. Sometimes students read independently. Other times I assign partners and a protocol for reading together. Sometimes we read portions of the novel aloud as a whole class or in small groups. I nd I need to give students time to read at least three times per week to keep them going. If we will be working on something else for 103

&

Whole Novels for the Whole Class

&

most of a class period, I have students read independently for about ten minutes when they enter the room. (More on reading time in Chapter 6.) During this time, I talk with individual students, observe their reading habits, and assess their sticky notes.

WHOLE GROUP RESPONSE PRACTICE

On the second day of reading, I like to have students choose a section from the previous nights reading to read aloud together and practice response. We do this as a whole class. Students or I read the section aloud, and students share their responses. I record them in a text box on my laptop that looks like a sticky note and project this for students to see. I generally do not ask questions or prescribe the content of their responses, but I use this process to model the general types of notes they should be writing. If we are working with a structured note type, I model the note format by asking students to help me follow the directions for writing, say, a language note. I do this at least two more times during the whole novel study at the beginning of class and then give students reading time.

WHOLE CLASS CHECK-INS

During a novel study, we spend about ve to ten minutes several days per week checking in as a whole class about how the reading is going. Students share excitement, general responses, frustrations, and questions. Sometimes a common question from students leads us to reread a section of text together, or a strong response to a character leads to some impromptu discussion of an idea from the book. However, I limit the scope and time frame for these discussions; their purpose is for students to feel part of a venture, as they have their individual experience in reading the book.

MINIPROJECTS

Generally in the second week, we use two or three days of class to work on a group miniproject. I use my assessments of students reading notes to diagnose the needs of the whole class or small groups of students and design collaborative projects that help address those needs. The projects are designed to aid students comprehension 104

Parts of the Whole

and critical thinking as they read and also to help them explore the authors development of a specic literary element that is a focus for the study. During these days, I always give students some time to read independently at the beginning of class. I share more about miniprojects in Chapter 7.

MIDWAY READING CHECK

I spot-monitor students progress in their reading and note taking informally on a daily basis and follow up with students and families after school when necessary. Midway through the study (or once a week if I can manage it), I do a quick check for completion either during class or by collecting books; I enter a grade in my grade book. I also use the opportunity to offer a comment or two to each student about his or her noteswhats working, an area to improve or nd additional challenge, or a response to the content of a particular note.

SUPPLEMENTAL EXPERIENCES

I pepper the days during the reading portion of the study with additional text materials that connect to the theme, content, or structure of the novel. We might spend a day reading and discussing an article that helps students understand the novels time period. We read and respond to a poem that connects to a theme in the novel. We watch a lm with a similar story line, and I use the opportunity to teach the idea of a moral dilemma, which will come up later in the book (I dont tell them, though).

CREATIVE WRITING

We often write creatively during the reading portion of the study. This might include writing letters to characters, writing poems, or writing monologues in the voices of characters. The assignment could also focus on emulating the style or structural element of the author in the original work. I take these opportunities to teach lessons on some of the formal aspects of ction writing, such as punctuating dialogue. Once students have nished the book, either during or after discussions, I often have them rewrite pieces of the novel for different purposes. 105

&

Whole Novels for the Whole Class

&

(See Chapter 5 for details.) Students usually share these with peers, giving and receiving feedback.

DISCUSSIONS

After students have nished reading the novel, we begin discussing the book. I describe the process for this in detail in the next chapter. For whole novel discussions, I allot at least three days. I prefer to run discussions for half of the class at a time, which means the other half of the class is working on a quiet independent activityusually creative writing related to the novel. The homework during discussions is based on prompts generated by each discussion group.

WRITING PROJECT

The whole novel discussions lead to writing projects. These could be creative or essay writing projects. Essays are based on debates or questions that arise in discussions. These could be based on only the novel, or they could explore a connection students have drawn between the novel and the supplemental texts weve read. Sometimes I draw out the writing process: I provide minilessons on writing each piece of the essay and give students time to outline and get feedback from their peers on their ideas. These essays usually involve multiple drafts. Other times, I give students a timed inclass essay assignment (always based on their own ideas and questions about the book). Sometimes students write multiple drafts of these in-class writing pieces, and other times they serve as formative assessments, and we leave it there.

&&&

Creative projects are always based on elements of the book weve studied or discussed. For example, following their reading of The House on Mango Street, which is written in short vignettes, students wrote their own collection of vignettes. Following the study of various novels with the journey motif, students wrote original journey stories. After studying Louise Fitzhughs Nobodys Family Is Going to Change, students experimented with rewriting scenes from different perspectives.

106

You might also like

- Using the Workshop Approach in the High School English Classroom: Modeling Effective Writing, Reading, and Thinking Strategies for Student SuccessFrom EverandUsing the Workshop Approach in the High School English Classroom: Modeling Effective Writing, Reading, and Thinking Strategies for Student SuccessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Sysmex Xs-800i1000i Instructions For Use User's ManualDocument210 pagesSysmex Xs-800i1000i Instructions For Use User's ManualSean Chen67% (6)

- A Dogs Purpose Complete Study GuideDocument47 pagesA Dogs Purpose Complete Study GuideAlexandra Stăncescu0% (3)

- The Organized Teacher's Guide to Children's LiteratureFrom EverandThe Organized Teacher's Guide to Children's LiteratureRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Reading Assessment Program Guide For Grade 8: Rubric and Reading PassagesFrom EverandReading Assessment Program Guide For Grade 8: Rubric and Reading PassagesNo ratings yet

- LitcirclesDocument14 pagesLitcirclesapi-260723936No ratings yet

- Novel Study Project Matrix - DivergentDocument1 pageNovel Study Project Matrix - Divergentapi-270398232No ratings yet

- The Book WhispererDocument27 pagesThe Book Whispererapi-33452231333% (3)

- How to Teach American Literature: Student Review Questions and TestsFrom EverandHow to Teach American Literature: Student Review Questions and TestsNo ratings yet

- The Elders Are Watching Text by David Bouchard and Art by Roy VickersDocument2 pagesThe Elders Are Watching Text by David Bouchard and Art by Roy Vickersapi-436064411No ratings yet

- Unit Plan Language Arts Grade 6 Tuck Everlasting Quarter 3Document2 pagesUnit Plan Language Arts Grade 6 Tuck Everlasting Quarter 3darkcaitNo ratings yet

- Reading Assessment Program Guide For Grade 4: Rubric and Reading PassagesFrom EverandReading Assessment Program Guide For Grade 4: Rubric and Reading PassagesNo ratings yet

- The Art of Coaching 2013 Summer InstituteDocument1 pageThe Art of Coaching 2013 Summer InstituteJossey-Bass EducationNo ratings yet

- Teaching Literature & Writing in the Secondary School ClassroomFrom EverandTeaching Literature & Writing in the Secondary School ClassroomNo ratings yet

- Student Practice Test Booklet in Reading and Writing: Upper Elementary Grades 3-5 Comprehension and Writing Teacher to TeacherFrom EverandStudent Practice Test Booklet in Reading and Writing: Upper Elementary Grades 3-5 Comprehension and Writing Teacher to TeacherNo ratings yet

- Teaching Writing to Children Part Two: Expository and Persuasive Writing: Teaching Writing, #2From EverandTeaching Writing to Children Part Two: Expository and Persuasive Writing: Teaching Writing, #2No ratings yet

- Teaching Writing to Children: Narrative and Descriptive Writing: Teaching Writing, #1From EverandTeaching Writing to Children: Narrative and Descriptive Writing: Teaching Writing, #1No ratings yet

- 327 TBWS Sample-1Document17 pages327 TBWS Sample-1Anindita PalNo ratings yet

- Practical Reading Strategies: Engaging Activities for Secondary StudentsFrom EverandPractical Reading Strategies: Engaging Activities for Secondary StudentsNo ratings yet

- Reading Assessment Program Guide For Grade 9: Rubric and Reading PassagesFrom EverandReading Assessment Program Guide For Grade 9: Rubric and Reading PassagesNo ratings yet

- DivergentunitplanDocument17 pagesDivergentunitplanapi-238521887100% (1)

- Grade 6 Unit Plan The Breadwinner 2021-22Document18 pagesGrade 6 Unit Plan The Breadwinner 2021-22Sibel DoğanNo ratings yet

- Guided Reading: Learn Proven Teaching Methods, Strategies, and Lessons for Helping Every Student Become a Better Reader and for Fostering Literacy Across the GradesFrom EverandGuided Reading: Learn Proven Teaching Methods, Strategies, and Lessons for Helping Every Student Become a Better Reader and for Fostering Literacy Across the GradesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (36)

- Lesson ObjectivesDocument3 pagesLesson Objectivesapi-242362084No ratings yet

- Flying lessons & Other stories collection edited by Ellen OhDocument1 pageFlying lessons & Other stories collection edited by Ellen OhEric Ovidiu MarcuNo ratings yet

- Summary Paragraph AssignmentDocument3 pagesSummary Paragraph Assignmentapi-238790253100% (1)

- Reviving The Essay PDFDocument31 pagesReviving The Essay PDFAnonymous SJGVlliHdNo ratings yet

- Reading Success for All Students: Using Formative Assessment to Guide Instruction and InterventionFrom EverandReading Success for All Students: Using Formative Assessment to Guide Instruction and InterventionNo ratings yet

- Bassriversheilamant Worksheet2Document1 pageBassriversheilamant Worksheet2api-233694703No ratings yet

- A Resource Guide For Middle School Teachers: Dr. Maya AngelouDocument21 pagesA Resource Guide For Middle School Teachers: Dr. Maya Angelouinput714No ratings yet

- SchmokerDocument7 pagesSchmokerChris Atkinson100% (2)

- Rubrics For Assessing Student Writing, Listening, and Speaking High SchoolDocument55 pagesRubrics For Assessing Student Writing, Listening, and Speaking High SchoolMa Teresa W. Hill100% (1)

- 3rd Grade Writing Rubric: Ideas & Content (Ideas) Organization Style (Voice, Word Choice, Fluency) Language SkillsDocument1 page3rd Grade Writing Rubric: Ideas & Content (Ideas) Organization Style (Voice, Word Choice, Fluency) Language Skillsdance423No ratings yet

- Teacher R - Week of 10-3-11Document7 pagesTeacher R - Week of 10-3-11Gonzalo PitpitNo ratings yet

- Analysis of The Fantasy Genre: Level 4 - Grade 5, Term 4 2015 Key Skills Needed To Develop: AnalysingDocument5 pagesAnalysis of The Fantasy Genre: Level 4 - Grade 5, Term 4 2015 Key Skills Needed To Develop: Analysingapi-318813104No ratings yet

- The Twits S2Document19 pagesThe Twits S2S TANCREDNo ratings yet

- Bellwork - CaughtyaDocument2 pagesBellwork - Caughtyaapi-314992364No ratings yet

- Mastering Grammar: The Sum of All Those Errors: Syntax, Usage, and MechanicsFrom EverandMastering Grammar: The Sum of All Those Errors: Syntax, Usage, and MechanicsNo ratings yet

- Mikyung Kim Wolf, Yuko Goto Butler - English Language Proficiency Assessments For Young Learners-Routledge (2017) PDFDocument295 pagesMikyung Kim Wolf, Yuko Goto Butler - English Language Proficiency Assessments For Young Learners-Routledge (2017) PDFEric CardovaNo ratings yet

- Paragraph Power PDFDocument128 pagesParagraph Power PDFendefan50% (2)

- Reading ComprehensionDocument3 pagesReading ComprehensionMaram Mostafa MokhtarNo ratings yet

- Book Report TemplateDocument7 pagesBook Report TemplateGustavo CastroNo ratings yet

- Poetry UnitDocument44 pagesPoetry Unitapi-352484036No ratings yet

- 3rd Grade March NewsletterDocument1 page3rd Grade March NewslettersstoubeNo ratings yet

- Alwtw Unit PlanDocument22 pagesAlwtw Unit Planapi-308997569No ratings yet

- 3rd Grade May NewsletterDocument1 page3rd Grade May NewslettersstoubeNo ratings yet

- Lemonade War Book Club ActivityDocument4 pagesLemonade War Book Club ActivityMadisen LehrNo ratings yet

- Picture-Book Unit Plan (Original)Document11 pagesPicture-Book Unit Plan (Original)api-266405967No ratings yet

- Stone Fox: by John Reynolds Gardiner Genre: Historical FictionDocument22 pagesStone Fox: by John Reynolds Gardiner Genre: Historical FictionKrista EtzwilerNo ratings yet

- Young Adult Literature in The English Curriculum Today:: BlasingameDocument9 pagesYoung Adult Literature in The English Curriculum Today:: BlasingameAnnaNo ratings yet

- Optional Daily Reading LogsDocument7 pagesOptional Daily Reading Logsapi-237648007100% (1)

- Short Story 8Document57 pagesShort Story 8tgun25No ratings yet

- How to Reach and Teach English Language Learners: Practical Strategies to Ensure SuccessFrom EverandHow to Reach and Teach English Language Learners: Practical Strategies to Ensure SuccessNo ratings yet

- Teaching Structure Without FormulaDocument17 pagesTeaching Structure Without Formulahicham96No ratings yet

- 5th Grade Opinion Argument Writing Continuum 11 7 12Document4 pages5th Grade Opinion Argument Writing Continuum 11 7 12api-252059788No ratings yet

- The Ten-Minute Classroom MakeoverDocument4 pagesThe Ten-Minute Classroom MakeoverJossey-Bass Education100% (1)

- The Vernal Pool (Excerpt From Visible Learners)Document7 pagesThe Vernal Pool (Excerpt From Visible Learners)Jossey-Bass EducationNo ratings yet

- Books Are TechnologiesDocument7 pagesBooks Are TechnologiesJossey-Bass EducationNo ratings yet

- Reading in The Wild: Curating A Classroom LibraryDocument8 pagesReading in The Wild: Curating A Classroom LibraryJossey-Bass Education100% (2)

- Take Control of Your Classroom Climate (Excerpt From Turnaround Tools For The Teenage Brain)Document4 pagesTake Control of Your Classroom Climate (Excerpt From Turnaround Tools For The Teenage Brain)Jossey-Bass EducationNo ratings yet

- Developing Positive Classroom Relationships (Excerpt From The First-Year Teacher's Survival Guide, 3rd Edition)Document4 pagesDeveloping Positive Classroom Relationships (Excerpt From The First-Year Teacher's Survival Guide, 3rd Edition)Jossey-Bass EducationNo ratings yet

- Tell Your Story (Excerpt From How To Prepare A Standout College Application)Document4 pagesTell Your Story (Excerpt From How To Prepare A Standout College Application)Jossey-Bass EducationNo ratings yet

- Example of A Classroom Instructional Unit GrantDocument4 pagesExample of A Classroom Instructional Unit GrantJossey-Bass EducationNo ratings yet

- Algebra & Beyond: Quick Lessons From Math Starters!Document3 pagesAlgebra & Beyond: Quick Lessons From Math Starters!Jossey-Bass EducationNo ratings yet

- Defining Clear Behavioral Expectations (Excerpt From Discipline in The Secondary Classroom, 3rd Edition)Document4 pagesDefining Clear Behavioral Expectations (Excerpt From Discipline in The Secondary Classroom, 3rd Edition)Jossey-Bass Education100% (1)

- Defining The Teacherpreneur (Excerpt From Teacherpreneurs)Document6 pagesDefining The Teacherpreneur (Excerpt From Teacherpreneurs)Jossey-Bass Education100% (1)

- Three Scenarios For Teacher Evaluation (Excerpt From Everyone at The Table)Document3 pagesThree Scenarios For Teacher Evaluation (Excerpt From Everyone at The Table)Jossey-Bass EducationNo ratings yet

- The Reading Apprenticeship Framework (Excerpt From Reading For Understanding, 2nd Edition)Document5 pagesThe Reading Apprenticeship Framework (Excerpt From Reading For Understanding, 2nd Edition)Jossey-Bass EducationNo ratings yet

- Where in The World Is Teach Like A Champion?Document1 pageWhere in The World Is Teach Like A Champion?Jossey-Bass EducationNo ratings yet

- If I Were A King or Queen: Creating Your Own Country (Excerpt From Don't Forget To Write For The Elementary Grades)Document3 pagesIf I Were A King or Queen: Creating Your Own Country (Excerpt From Don't Forget To Write For The Elementary Grades)Jossey-Bass EducationNo ratings yet

- Testing (Excerpt From The New American High School)Document5 pagesTesting (Excerpt From The New American High School)Jossey-Bass EducationNo ratings yet

- Coaching Sentence Stems (Excerpt From The Art of Coaching)Document4 pagesCoaching Sentence Stems (Excerpt From The Art of Coaching)Jossey-Bass Education100% (2)

- Read, Learn, and Earn With Read4Credit CoursesDocument2 pagesRead, Learn, and Earn With Read4Credit CoursesJossey-Bass EducationNo ratings yet

- Marshall Memo 481Document14 pagesMarshall Memo 481Jossey-Bass EducationNo ratings yet

- Tips For Your Professional Development Book ClubDocument5 pagesTips For Your Professional Development Book ClubJossey-Bass Education100% (1)

- Preparing For Co-Teaching (Excerpt From The Co-Teaching Book of Lists)Document3 pagesPreparing For Co-Teaching (Excerpt From The Co-Teaching Book of Lists)Jossey-Bass EducationNo ratings yet

- Making Lessons Meaningful (Excerpt From The Ten-Minute Inservice)Document4 pagesMaking Lessons Meaningful (Excerpt From The Ten-Minute Inservice)Jossey-Bass Education100% (1)

- Understanding Story Structure With Story Trails and History Maps, Grades K-5Document4 pagesUnderstanding Story Structure With Story Trails and History Maps, Grades K-5Jossey-Bass Education100% (1)

- Meet Our Authors at ASCD!Document1 pageMeet Our Authors at ASCD!Jossey-Bass EducationNo ratings yet

- Testing 1,2,3 - . - Testing (Excerpt From Reading Without Limits)Document6 pagesTesting 1,2,3 - . - Testing (Excerpt From Reading Without Limits)Jossey-Bass EducationNo ratings yet

- How To Be The Next President of The United States! (Excerpt From Don't Forget To Write For The Elementary Grades)Document4 pagesHow To Be The Next President of The United States! (Excerpt From Don't Forget To Write For The Elementary Grades)Jossey-Bass EducationNo ratings yet

- Get Healthy (Excerpt From Fearless Feeding)Document5 pagesGet Healthy (Excerpt From Fearless Feeding)Jossey-Bass EducationNo ratings yet

- Supporting Students Who Need More Help (Excerpt From Boosting Executive Skills in The Classroom)Document6 pagesSupporting Students Who Need More Help (Excerpt From Boosting Executive Skills in The Classroom)Jossey-Bass EducationNo ratings yet

- Pom Final On Rice MillDocument21 pagesPom Final On Rice MillKashif AliNo ratings yet

- Fernandez ArmestoDocument10 pagesFernandez Armestosrodriguezlorenzo3288No ratings yet

- IGCSE Chemistry Section 5 Lesson 3Document43 pagesIGCSE Chemistry Section 5 Lesson 3Bhawana SinghNo ratings yet

- Reg FeeDocument1 pageReg FeeSikder MizanNo ratings yet

- Inventory Control Review of LiteratureDocument8 pagesInventory Control Review of Literatureaehupavkg100% (1)

- Account Statement From 30 Jul 2018 To 30 Jan 2019Document8 pagesAccount Statement From 30 Jul 2018 To 30 Jan 2019Bojpuri OfficialNo ratings yet

- Quality Management in Digital ImagingDocument71 pagesQuality Management in Digital ImagingKampus Atro Bali0% (1)

- Olympics Notes by Yousuf Jalal - PDF Version 1Document13 pagesOlympics Notes by Yousuf Jalal - PDF Version 1saad jahangirNo ratings yet

- Experiences from OJT ImmersionDocument3 pagesExperiences from OJT ImmersionTrisha Camille OrtegaNo ratings yet

- SQL Guide AdvancedDocument26 pagesSQL Guide AdvancedRustik2020No ratings yet

- Tech Data: Vultrex Production & Drilling CompoundsDocument2 pagesTech Data: Vultrex Production & Drilling CompoundsJeremias UtreraNo ratings yet

- WSP Global EnvironmentDocument20 pagesWSP Global EnvironmentOrcunNo ratings yet

- KSEB Liable to Pay Compensation for Son's Electrocution: Kerala HC CaseDocument18 pagesKSEB Liable to Pay Compensation for Son's Electrocution: Kerala HC CaseAkhila.ENo ratings yet

- The Ultimate Advanced Family PDFDocument39 pagesThe Ultimate Advanced Family PDFWandersonNo ratings yet

- Energy AnalysisDocument30 pagesEnergy Analysisca275000No ratings yet

- 8.1 Interaction Diagrams: Interaction Diagrams Are Used To Model The Dynamic Aspects of A Software SystemDocument13 pages8.1 Interaction Diagrams: Interaction Diagrams Are Used To Model The Dynamic Aspects of A Software SystemSatish JadhaoNo ratings yet

- Resume of Deliagonzalez34 - 1Document2 pagesResume of Deliagonzalez34 - 1api-24443855No ratings yet

- Merchandising Calender: By: Harsha Siddham Sanghamitra Kalita Sayantani SahaDocument29 pagesMerchandising Calender: By: Harsha Siddham Sanghamitra Kalita Sayantani SahaSanghamitra KalitaNo ratings yet

- Udaan: Under The Guidance of Prof - Viswanathan Venkateswaran Submitted By, Benila PaulDocument22 pagesUdaan: Under The Guidance of Prof - Viswanathan Venkateswaran Submitted By, Benila PaulBenila Paul100% (2)

- Android software download guideDocument60 pagesAndroid software download guideRizky PradaniNo ratings yet

- Rubber Chemical Resistance Chart V001MAR17Document27 pagesRubber Chemical Resistance Chart V001MAR17Deepak patilNo ratings yet

- "Behind The Times: A Look at America's Favorite Crossword," by Helene HovanecDocument5 pages"Behind The Times: A Look at America's Favorite Crossword," by Helene HovanecpspuzzlesNo ratings yet

- STAT455 Assignment 1 - Part ADocument2 pagesSTAT455 Assignment 1 - Part AAndyNo ratings yet

- Zelev 1Document2 pagesZelev 1evansparrowNo ratings yet

- DELcraFT Works CleanEra ProjectDocument31 pagesDELcraFT Works CleanEra Projectenrico_britaiNo ratings yet

- Report Emerging TechnologiesDocument97 pagesReport Emerging Technologiesa10b11No ratings yet

- Portfolio Artifact Entry Form - Ostp Standard 3Document1 pagePortfolio Artifact Entry Form - Ostp Standard 3api-253007574No ratings yet

- 5054 w11 QP 11Document20 pages5054 w11 QP 11mstudy123456No ratings yet

- BPL Millipacs 2mm Hardmetrics RarDocument3 pagesBPL Millipacs 2mm Hardmetrics RarGunter BragaNo ratings yet