Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Rule 111 Cases

Uploaded by

IzrahCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Rule 111 Cases

Uploaded by

IzrahCopyright:

Available Formats

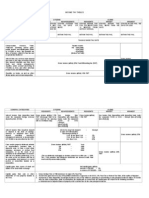

RULE 111-PROSECUTION OF CIVIL ACTIONS (1) BARCELIZA P. CAPISTRANO LIMCUANDO and FE S. SUMIRAN G.R. No. 152413 DE CASTRO, J.

: vs. DARRYL

February 13, 2009 LEONARDO-

time the adverted criminal case was instituted against her, respondents essentially admitted that fraud attended the execution of the subject deed of sale and that, therefore, respondents should be deemed to have assailed the validity of the said contract. Issue: Whether the deed of sale is valid. Held: The petition devoid of merit. Certainly, petitioners action for annulment of the subject deed should be dismissed based on Article 1397 of the Civil Code which provides that the person who employed fraud cannot base his action for the annulment of contracts upon such flaw of the contract. Petitioner is, therefore, precluded from seeking the annulment of the said contract based on the fraud which she herself has caused. The theory of petitioner that the respondents should be deemed to have themselves assailed the validity of the subject deed of sale, since the civil aspect of the criminal case for estafa was impliedly instituted with the filing of said criminal action, is bereft of legal basis. The civil action impliedly instituted in a criminal case pertains only to the recovery of civil liability arising from the offense charged. Such civil action includes recovery of indemnity under the Revised Penal Code, and damages under Articles 32, 33, 34 and 2176 of the Civil Code of the Philippines arising from the same act or omission of the accused. In other words, the civil action which is deemed impliedly instituted with the criminal action is the recovery of indemnity or damages under the Revised Penal Code and specifically enumerated articles of the Civil Code. The action to annul the subject deed of sale is obviously not among the civil actions that are deemed impliedly instituted with the criminal action. Thus, respondents active participation in the prosecution of petitioner for the crime of estafa, as well as their concession that fraud attended the execution of the said deed of sale, would have significance only as to the recovery of civil indemnity arising from the said crime. The trial court did not err when it held that the action to annul the deed of sale should be ventilated in a separate civil action, notwithstanding petitioners conviction in the criminal action. (2) RAMON A. ALBERT vs. THE SANDIGANBAYAN, and THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES G.R. No. 164015 February 26, 2009 CARPIO, J.:

A petition for review of the CAs Decision (Sept 28, 2001) and the Resolution (Feb 1, 2002), which affirmed the Amended Decision (Jan 23, 1995) rendered by the RTC, San Pablo City, Laguna in Civil Case No. SP 3757. Said civil case was an action for the annulment of a deed of sale or for the repurchase of real property Petitioner owned a parcel of land. She sold this parcel of land with a right of repurchase in favor of spouses Felimon Zuasola and Anita Subida. Petitioner sold half of the same parcel of land to respondents for the price of P75,000.00 on the understanding that respondents shall pay the amount of P10,000.00 as partial payment and the balance to be paid by monthly installments. Petitioner received the partial payment of P10,000.00 but signed a deed of absolute sale. Subsequently, respondents defaulted on their monthly installments. Petitioner repeatedly demanded for the payment of the balance of P65,000.00 from respondents but the latter refused to pay and claimed that they had already fully satisfied the consideration for the disputed land according to the terms of the subject deed of sale. Respondents learned afterwards that the disputed land had been previously sold by the petitioner to the spouses Zuasola and Subida which led respondents to file a criminal complaint for estafa against petitioner. Petitioner was eventually convicted. On August 19, 1991, petitioner repurchased the parcel of land from the spouses Zuasola and Subida. She also offered to repurchase from respondents the portion of the disputed land which she sold to them but the latter refused. Petitioner filed a complaint for the annulment of the subject deed of sale alleging that the sale was a nullity from the beginning and that respondents even assailed its validity in the previously mentioned criminal case for estafa against petitioner. As an alternative cause of action, petitioner sought to repurchase the disputed land from respondents. In their Answer with Counterclaim, respondents admitted the material facts of the case but chiefly contended that they purchased the subject land from petitioner in consideration of the P10,000.00 only and that they never assailed the validity of the subject deed of sale in the estafa case. The RTC sustained the validity of the subject deed of sale and denied the right of the petitioner to repurchase the disputed land from the respondents. On appeal by both petitioner and respondents, the CA affirmed the judgment of the RTC. Hence, the instant petition for review. Petitioner asserts that the subject deed of sale is null and void. The cause of this obligation, as an indispensable element of a contract, is allegedly false because of the fact that, prior to the sale of the disputed land in favor of the respondents in 1989, petitioner had the same land sold with right of repurchase in favor of spouses Zuasola and Subida way back in 1985. Petitioners asserts that her redemption of the disputed land from spouses Zuasola and Subida does not cure a void contract (i.e. the deed of sale in favor of respondents). In addition, petitioner argues that, at the

A petition for certiorari of the Resolutions (10 Feb 2004 and 3 May 2004) of the Sandiganbayan. The 10 Feb2004 Resolution granted the prosecutions Motion to Admit the Amended Information. The 3 May 2004 Resolution denied the Motion For Reconsideration of petitioner Ramon A. Albert (petitioner). On 24 March 1999, the Special Prosecution Officer (SPO) II of the Office of the Ombudsman for Mindanao charged petitioner and his co-accused, Favio D. Sayson and Arturo S. Asumbrado, before the Sandiganbayan with violation of Section 3(e) of Republic Act No. 3019 (RA 3019) or the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act in Criminal Case No. 25231. On 25 May 1999, petitioner filed a Motion to Dismiss Criminal Case No. 25231 on the following grounds: (1) the accused (petitioner) was denied due process of law; (2) the Office of the Ombudsman did not acquire jurisdiction over the person of the accused; (3) the constitutional rights of the accused to a speedy

disposition of cases and to a speedy trial were violated; and (4) the resolution dated 26 Feb1999 finding the accused guilty of violation of Section 3(e) of RA 3019 is not supported by evidence. On 26 Nov 2001, the Sandiganbayan denied petitioners Motion to Dismiss and ordered the prosecution to conduct a reinvestigation of the case with respect to petitioner. In a Memorandum, the SPO who conducted the reinvestigation recommended to the Ombudsman that the indictment against petitioner be reversed for lack of probable cause. However, the Ombudsman, in an Order, disapproved the Memorandum and directed the Office of the Special Prosecutor to proceed with the prosecution of the criminal case. Petitioner filed a Motion for Reconsideration of the Order of the Ombudsman. In a Manifestation, the SPO informed the Sandiganbayan of the Ombudsmans denial of petitioners motion for reconsideration. On even date, the prosecution filed an Ex-Parte Motion to Admit Amended Information. This ex-parte motion was withdrawn by the prosecution with the intention of filing a Motion for Leave to Admit Amended Information. The scheduled arraignment of petitioner was reset to 1 Dec 2003. On 7 Oct 2003, the prosecution filed a Motion for Leave to Admit Amended Information. Petitioner opposed the motion, alleging that the amendment made on the information is substantial and, therefore, not allowed after arraignment (Petitioner was provisionally arraigned when his Motion to Lift Hold Departure Order and to be Allowed to Travel was granted by the Sandiganbayan). Sandiganbayan: Sandiganbayan granted the prosecutions Motion to Admit Amended Information. At the outset, the Sandiganbayan explained that "gross neglect of duty" which falls under Section 3(f) of RA 3019 is different from "gross inexcusable negligence" under Section 3(e). However, the Sandiganbayan also held that even granting that the amendment of the information be formal or substantial, the prosecution could still effect the same in the event that the accused had not yet undergone a permanent arraignment. And since the arraignment of petitioner on 13 March 2001 was merely "provisional," then the prosecution may still amend the information either in form or in substance. Petitioner filed a Motion for Reconsideration, which was denied by the Sandiganbayan. Hence this petition. Issues: Whether the Sandiganbayan Should Admit the Amended Information Held: The petition has no merit.

Sec. 14. Amendment or Substitution.-- A complaint or information may be amended, in form or in substance, without leave of court, at any time before the accused enters his plea. After the plea and during the trial, a formal amendment may only be made with leave of court and when it can be done without causing prejudice to the rights of the accused. xxx An arraignment is that stage where in the mode and manner required by the rules, an accused, for the first time, is granted the opportunity to know the precise charge that confronts him. The accused is formally informed of the charges against him, to which he enters a plea of guilty or not guilty. As an indispensable requirement of due process, an arraignment cannot be regarded lightly or brushed aside peremptorily. The practice of the Sandiganbayan of conducting "provisional" or "conditional" arraignments is not sanctioned by the Revised Internal Rules of the Sandiganbayan or by the regular Rules of Court. However, in People v. Espinosa, this Court tangentially recognized such practice, provided that the alleged conditions attached thereto should be "unmistakable, express, informed and enlightened." Moreover, the conditions must be expressly stated in the Order disposing of the arraignment; otherwise, the arraignment should be deemed simple and unconditional. In the present case, the arraignment of petitioner is reflected in the Minutes of the Sandiganbayan Proceedings which merely states that the "[a]ccused when arraigned entered a plea of not guilty. The Motion to Travel is granted subject to the usual terms and conditions imposed on accused persons travelling (sic) abroad." Nothing on record is indicative of the provisional or conditional nature of the arraignment. Hence, following the doctrine laid down in Espinosa, the arraignment of petitioner should be deemed simple and unconditional. 1.1 The rules mandate that after a plea is entered, only a formal amendment of the Information may be made but with leave of court and only if it does not prejudice the rights of the accused. Petitioner contends that replacing "gross neglect of duty" with "gross inexcusable negligence" is a substantial amendment of the Information which is prejudicial to his rights. He asserts that under the amended information, he has to present evidence that he did not act with "gross inexcusable negligence," evidence he was not required to present under the original information. To bolster his argument, petitioner refers to the 10 Feb 2004 Resolution of the Sandiganbayan which ruled that the change "constitutes substantial amendment considering that the possible defense of the accused may divert from the one originally intended." We are not convinced. Petitioner is charged with violation of Section 3(e) of RA 3019. This crime has the following essential elements: 1. The accused must be a public officer discharging administrative, judicial or official functions; 2. He must have acted with manifest partiality, evident bad faith or gross inexcusable negligence; and 3. His action caused any undue injury to any party, including the government, or gave any private party unwarranted benefits, advantage or preference in the discharge of his functions.

On Whether the Sandiganbayan Should Admit the Amended Information Petitioner contends that under the above section, only a formal amendment of the information may be made after a plea. The rule does not distinguish between a plea made during a "provisional" or a "permanent" arraignment. Since petitioner already entered a plea of "not guilty" during the 13 March 2001 arraignment, then the information may be amended only in form. Section 14 of Rule 110 of the Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure provides:

The second element provides the different modes by which the crime may be committed, that is, through "manifest partiality," "evident bad faith," or "gross inexcusable negligence." In Uriarte v. People, this Court explained that Section 3(e) of RA 3019 may be committed either by dolo, as when the accused acted with evident bad faith or manifest partiality, or by culpa, as when the accused committed gross inexcusable negligence. There is "manifest partiality" when there is a clear, notorious, or plain inclination or predilection to favor one side or person rather than another. "Evident bad faith" connotes not only bad judgment but also palpably and patently fraudulent and dishonest purpose to do moral obliquity or conscious wrongdoing for some perverse motive or ill will. "Evident bad faith" contemplates a state of mind affirmatively operating with furtive design or with some motive or self-interest or ill will or for ulterior purposes. "Gross inexcusable negligence" refers to negligence characterized by the want of even the slightest care, acting or omitting to act in a situation where there is a duty to act, not inadvertently but willfully and intentionally, with conscious indifference to consequences insofar as other persons may be affected. The original information filed against petitioner alleged that he acted with "evident bad faith and manifest partiality and or (sic) gross neglect of duty." The amended information, on the other hand, alleges that petitioner acted with "evident bad faith and manifest partiality and/or gross inexcusable negligence." Simply, the amendment seeks to replace "gross neglect of duty" with "gross inexcusable negligence." Given that these two phrases fall under different paragraphs of RA 3019 specifically, "gross neglect of duty" is under Section 3(f) while "gross inexcusable negligence" is under Section 3(e) of the statutethe question remains whether or not the amendment is substantial and prejudicial to the rights of petitioner. 1.2 The test as to when the rights of an accused are prejudiced by the amendment of a complaint or information is when a defense under the complaint or information, as it originally stood, would no longer be available after the amendment is made, and when any evidence the accused might have, would be inapplicable to the complaint or information as amended. On the other hand, an amendment which merely states with additional precision something which is already contained in the original information and which, therefore, adds nothing essential for conviction for the crime charged is an amendment to form that can be made at anytime. In this case, the amendment entails the deletion of the phrase "gross neglect of duty" from the Information. Although this may be considered a substantial amendment, the same is allowable even after arraignment and plea being beneficial to the accused. As a replacement, "gross inexcusable negligence" would be included in the Information as a modality in the commission of the offense. This Court believes that the same constitutes an amendment only in form. In Sistoza v. Desierto, the Information charged the accused with violation of Section 3(e) of RA 3019, but specified only "manifest partiality" and "evident bad faith" as the modalities in the commission of the offense charged. "Gross inexcusable negligence" was not mentioned in the Information. Nonetheless, this Court held that the said section is committed by dolo or culpa, and although the Information may have alleged only one of the modalities of committing the offense, the other mode is deemed included in the accusation to allow proof thereof. In so ruling, this Court applied by analogy the pronouncement in Cabello v. Sandiganbayan where an

accused charged with willful malversation was validly convicted of the same felony of malversation through negligence when the evidence merely sustained the latter mode of perpetrating the offense. The Court held that a conviction for a criminal negligent act can be had under an information exclusively charging the commission of a willful offense upon the theory that the greater includes the lesser offense. Thus, we hold that the inclusion of "gross inexcusable negligence" in the Information, which merely alleges "manifest partiality" and "evident bad faith" as modalities in the commission of the crime under Section 3(e) of RA 3019, is an amendment in form. YAP VS. CABALES G.R. NO. 159186 JUNE 5, 2009 FACTS: Petitioner Jesse Y. Yap and his spouse Bessie Yap are engaged in the real estate business through their company Primetown Property Group. Yap purchased several real properties from a certain Evelyn Te. In consideration of said purchases, petitioner issued several BPI postdated checks to Evelyn. Thereafter, spouses Orlando and Mergyl Mirabueno and spouses Charlie and Jovita Dimalanta, rediscounted the checks from Evelyn. Some of the checks were dishonour by reason of account closed. Despite of the demand, Yap failed to pay the amounts represented by the said checks. Spouses Mirabueno filed a civil action for collection of sum of money against Yap. Subsequently, the Office of the City Prosecutor of General Santos City filed several informations for violation of BP 22 against the petitioner. In the criminal cases, Yap filed separate motions to suspend proceedings on account of the existence of a prejudicial question. The MCTC denied the motions for lack of merit. On appeal, the RTC likewise denied the petition. CA rendered a Decision dismissing the petition for lack of merit. The CA opined that Civil Case Nos. 6231 and 6238 did not pose a prejudicial question to the prosecution of the petitioner for violation of B.P. Blg. 22. Hence, this appeal. ISSUE: Whether or not there exists a prejudicial question that necessitates the suspension of the proceedings in the MTCC. HELD: None. A prejudicial question generally exists in a situation where a civil action and a criminal action are both pending, and there exists in the former an issue that must be preemptively resolved before the latter may proceed, because howsoever the issue raised in the civil action is resolved would be determinative juris et de jure of the guilt or innocence of the accused in the criminal case. The rationale behind the principle of prejudicial question is to avoid two conflicting decisions. It has two essential elements: (i) the civil action involves an issue similar or intimately related to the issue raised in the criminal action; and (ii) the resolution of such issue determines whether or not the criminal action may proceed. If both civil and criminal cases have similar issues, or the issue in one is intimately related to the issues raised in the other, then a prejudicial question would likely exist, provided the other element or characteristic is satisfied. It must appear not only that the civil case involves the same facts upon which the criminal prosecution would be based, but also that the resolution of the issues raised in the civil action would be necessarily determinative of the guilt or innocence of the accused. If the resolution of the

issue in the civil action will not determine the criminal responsibility of the accused in the criminal action based on the same facts, or if there is no necessity that the civil case be determined first before taking up the criminal case, the civil case does not involve a prejudicial question. Neither is there a prejudicial question if the civil and the criminal action can, according to law, proceed independently of each other. PIMENTEL V. PIMENTEL G.R. NO. 172060, September 3, 2010 Facts: This is a petition for review assailing the Decision of the Court of Appeals, promulgated on 20 March 2006, in CAG.R. SP No. 91867. On 25 October 2004, Maria Chrysantine Pimentel y Lacap (private respondent) filed an action for frustrated parricide against Joselito R. Pimentel (petitioner), docketed as Criminal Case No. Q-04- 130415, before the Regional Trial Court of Quezon City, which was raffled to Branch 223 (RTC Quezon City). On 7 February 2005, petitioner received summons to appear before the Regional Trial Court of Antipolo City, Branch 72 (RTC Antipolo) for the pre-trial and trial of Civil Case No. 04-7392 (Maria Chrysantine Lorenza L. Pimentel v. Joselito Pimentel) for Declaration of Nullity of Marriage under Section 36 of the Family Code on the ground of psychological incapacity. Petitioner asserted that since the relationship between the offender and the victim is a key element in parricide, the outcome of Civil Case No. 04-7392 would have a bearing in the criminal case filed against him before the RTC Quezon City. The court stated that the pendency of the case before the RTC Antipolo is not a prejudicial question that warrants the suspension of the criminal case before it Petitioner herein appealed the case before the Court of Appeals which affirmed the decision of the lower court Issue: Whether or not the resolution of the action for annulment of marriage is a prejudicial question that warrants the suspension of the criminal case for frustrated parricide against the petitioner. Held. NO. The rule is clear that the civil action must be instituted first before the filing of the criminal action. As in the case before, the civil action for annulment of marriage was filed after the filing of the criminal complaint for frustrated parricide. Also, there is a prejudicial question when a civil action and a criminal action are both pending, and there exists in the civil action an issue which must be preemptively resolved before the criminal action may proceed because howsoever the issue raised in the civil action is resolved would be determinative of the guilt or innocence of the accused in the criminal case. A prejudicial question is defined as: x x x one that arises in a case the resolution of which is a logical antecedent of the issue involved therein, and the cognizance of which pertains to another tribunal. It is a question based on a fact distinct and separate from the crime but so intimately connected with it that it determines the guilt or innocence of the accused, and for it to suspend the criminal action, it must appear not only that said case involves facts intimately related to those upon which the criminal prosecution would be based but also that in the resolution of the issue or issues raised in

the civil case, the guilt or innocence of the accused would necessarily be determined. HEIRS OF SIMON V. CHAN G.R. NO. 157547, February 23, 2011 Facts: There is no independent civil action to recover the civil liability arising from the issuance of an unfunded check prohibited and punished under Batas Pambansa Bilang 22 (BP 22). Respondent herein, filed a case at the City Prosecutors Office of Manila a case of B.P. 22 against the petitioner, by issuing a LandBank check No. 0007280 worth 366,000.00. After sometime, respondent herein filed another case against petitioner for civil damages arising from the same transactions at Pasay City. Petitioner herein filed in Pasay a Motion to Dismiss due to litis pendencia, at which instance, the Pasay Court dismissed the case against the petitioner. Appeal was likewise denied the the lower court. The Court of Appeals upheld the ruling of the lower court. Issue: Whether or not the institution of a criminal case (B.P. 22), the complainant can reserved his/her right to file a civil case. Held. NO. Regardless, therefore, of whether or not a special law so provides, indemnification of the offended party may be had on account of the damage, loss or injury directly suffered as a consequence of the wrongful act of another Section 1. Institution of criminal and civil actions. - (a) When a criminal action is instituted, the civil action for the recovery of civil liability arising from the offense charged shall be deemed instituted with the criminal action unless the offended party waives the civil action, reserves the right to institute it separately or institutes the civil action prior to the criminal action. The reservation of the right to institute separately the civil action shall be made before the prosecution starts presenting its evidence and under circumstances affording the offended party a reasonable opportunity to make such reservation. Except as otherwise provided in these Rules, no filing fees shall be required for actual damages. No counterclaim, cross-claim or third-party complaint may be filed by the accused in the criminal case, but any cause of action which could have been the subject thereof may be litigated in a separate civil action. (1a) (b) The criminal action for violation of Batas Pambansa Blg. 22 shall be deemed to include the corresponding civil action. No reservation to file such civil action separately shall be allowed. To repeat, Chans separate civil action to recover the amount of the check involved in the prosecution for the violation of BP 22 could not be independently maintained under both Supreme Court Circular 57- 97 and the provisions of Rule 111 of the Rules of Court, notwithstanding the allegations of fraud and deceit.

You might also like

- SC ruling on Estafa elementsDocument4 pagesSC ruling on Estafa elementsIzrahNo ratings yet

- Sta. Clara Homeowners' Association v. Sps. GastonDocument4 pagesSta. Clara Homeowners' Association v. Sps. GastonIzrahNo ratings yet

- Legal Forms (2009)Document84 pagesLegal Forms (2009)Sui100% (10)

- SC ruling on Estafa elementsDocument4 pagesSC ruling on Estafa elementsIzrahNo ratings yet

- China Banking Corporation Vs OliverDocument3 pagesChina Banking Corporation Vs OliverIzrah100% (1)

- Civil Law Rev Cases Nos. 34-61Document46 pagesCivil Law Rev Cases Nos. 34-61IzrahNo ratings yet

- Rule 114 OkabeDocument4 pagesRule 114 OkabeIzrahNo ratings yet

- 122-125 Quidet, Balaba, OlivoDocument5 pages122-125 Quidet, Balaba, OlivoIzrahNo ratings yet

- Rule 110Document5 pagesRule 110IzrahNo ratings yet

- IncomeTax Tables (Annex B)Document9 pagesIncomeTax Tables (Annex B)IzrahNo ratings yet

- Succession 31 35Document6 pagesSuccession 31 35IzrahNo ratings yet

- Corpuz vs. Sto. Tomas G.R. No. 186571 August 11, 2010Document3 pagesCorpuz vs. Sto. Tomas G.R. No. 186571 August 11, 2010IzrahNo ratings yet

- Chapter I Income TaxesDocument48 pagesChapter I Income TaxesLovely Alyssa BonifacioNo ratings yet

- Teh Vs CADocument2 pagesTeh Vs CAIzrah100% (1)

- Jose Vs BoyonDocument3 pagesJose Vs BoyonIzrahNo ratings yet

- Santos Vs PNOCDocument4 pagesSantos Vs PNOCIzrahNo ratings yet

- 11 Jesalva Vs PPDocument10 pages11 Jesalva Vs PPIzrahNo ratings yet

- COURT RULES ON VALIDITY OF SERVICE OF SUMMONSDocument3 pagesCOURT RULES ON VALIDITY OF SERVICE OF SUMMONSIzrahNo ratings yet

- Rosary Guide Cute Size1Document2 pagesRosary Guide Cute Size1IzrahNo ratings yet

- Laws On Public OfficialsDocument16 pagesLaws On Public OfficialsIzrahNo ratings yet

- RPC Book 1Document131 pagesRPC Book 1IzrahNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- United States v. Edward G. Novotny, 968 F.2d 22, 10th Cir. (1992)Document8 pagesUnited States v. Edward G. Novotny, 968 F.2d 22, 10th Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Ethical Plea Bargaining Limits and ObligationsDocument23 pagesEthical Plea Bargaining Limits and ObligationsleiliuNo ratings yet

- Garofano Plea AgreementDocument12 pagesGarofano Plea AgreementThe Republican/MassLive.comNo ratings yet

- (34.1) G.R. No. 241012 - People v. Torres y PalisDocument2 pages(34.1) G.R. No. 241012 - People v. Torres y PalisKarina GarciaNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law CasesDocument98 pagesCriminal Law Caseslanielaurio11No ratings yet

- FAQS Criminal Law PDFDocument44 pagesFAQS Criminal Law PDFSean Robert L. AndradeNo ratings yet

- (10 People v. Derilo, 271 SCRA 633, G.R. No. 117818, April 18, 1997 PDFDocument35 pages(10 People v. Derilo, 271 SCRA 633, G.R. No. 117818, April 18, 1997 PDFABCDNo ratings yet

- Richard H YinkoDocument3 pagesRichard H YinkoSheboyganOversightNo ratings yet

- Crime DetectionDocument7 pagesCrime DetectionTony Cabrestante100% (1)

- Chapter Wise CRPCDocument26 pagesChapter Wise CRPCNilesh TayadeNo ratings yet

- 92 G.R. No. L-16790Document2 pages92 G.R. No. L-16790RomNo ratings yet

- Wander Perry Craig 102523 88-C-11611Document40 pagesWander Perry Craig 102523 88-C-11611juanguzman5No ratings yet

- United States v. Prilliman, 4th Cir. (2009)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Prilliman, 4th Cir. (2009)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- In The Supreme Court of Mississippi NO. 2021-IA-00632-SCTDocument19 pagesIn The Supreme Court of Mississippi NO. 2021-IA-00632-SCTthe kingfish0% (1)

- Midterm Cases EvidenceDocument309 pagesMidterm Cases EvidenceAiai Harder - GustiloNo ratings yet

- United States v. Travis Wright, 4th Cir. (2011)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Travis Wright, 4th Cir. (2011)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- People vs. Gumimba Case DigestDocument2 pagesPeople vs. Gumimba Case DigestJamie Berry100% (4)

- People of The Philippines vs. Macadaeg - Statcon (Obiter Dictum)Document9 pagesPeople of The Philippines vs. Macadaeg - Statcon (Obiter Dictum)Lorelain Valerie ImperialNo ratings yet

- United States v. Ulysses Gonzalez, 3rd Cir. (2012)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Ulysses Gonzalez, 3rd Cir. (2012)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Binay vs. Sandiganbayan, G.R. Nos. 120681-83 (Case Digest)Document1 pageBinay vs. Sandiganbayan, G.R. Nos. 120681-83 (Case Digest)AycNo ratings yet

- Dionaldo vs. DacuycuyDocument2 pagesDionaldo vs. DacuycuySAMANTHA VILLANUEVA MAKAYANNo ratings yet

- 72650213350Document3 pages72650213350Moustapha AhmatNo ratings yet

- Former Senator Kalani English - Plea AgreementDocument39 pagesFormer Senator Kalani English - Plea AgreementIan LindNo ratings yet

- People v. MoralesDocument8 pagesPeople v. MoralesRMN Rommel DulaNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 160451.Document4 pagesG.R. No. 160451.Francess PiloneoNo ratings yet

- Pre Trial Brief 1Document3 pagesPre Trial Brief 1Kaye TagsNo ratings yet

- Drag Queen MummyDocument21 pagesDrag Queen MummyAnna ReynoldsNo ratings yet

- Regional Trial Court Branch 23, Makati City, Metro ManilaDocument16 pagesRegional Trial Court Branch 23, Makati City, Metro ManilaRen ConchaNo ratings yet

- UNITED STATES v. ORLANDO ORTIZ-TORRES, A/K/A LANDY, A/K/A ORLANDO TORRES-ORTIZ, UNITED STATES v. OMAR COSME-PIRI, A/K/A CHIQUITO, UNITED STATES v. RAYMOND TORRES-SANTIAGO, UNITED STATES v. JOSÉ RENOVALES-VÉLEZ, A/K/A PIPE, UNITED STATES v. JULIO MATTEI-ALBIZU, 449 F.3d 61, 1st Cir. (2006)Document26 pagesUNITED STATES v. ORLANDO ORTIZ-TORRES, A/K/A LANDY, A/K/A ORLANDO TORRES-ORTIZ, UNITED STATES v. OMAR COSME-PIRI, A/K/A CHIQUITO, UNITED STATES v. RAYMOND TORRES-SANTIAGO, UNITED STATES v. JOSÉ RENOVALES-VÉLEZ, A/K/A PIPE, UNITED STATES v. JULIO MATTEI-ALBIZU, 449 F.3d 61, 1st Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Marcelo vs. C.ADocument10 pagesMarcelo vs. C.Abam112190No ratings yet