Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Can PCT help differentiate bacterial infection from inflammation

Uploaded by

Andi BintangOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Can PCT help differentiate bacterial infection from inflammation

Uploaded by

Andi BintangCopyright:

Available Formats

Downloaded from ard.bmj.com on July 3, 2012 - Published by group.bmj.

com

337

EXTENDED REPORT

Can procalcitonin measurement help in differentiating between bacterial infection and other kinds of inflammatory processes?

I Delvaux, M Andr, M Colombier, E Albuisson, F Meylheuc, R-J Bgue, J-C Piette, O Aumatre

.............................................................................................................................

Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:337340

See end of article for authors affiliations

.......................

Correspondence to: Professor O Aumatre, Department of Internal Medicine, Gabriel Montpied Hospital, groupe hospitalier Saint-Jacques, BP 69, 63003 Clermont-Ferrand Cedex 1, France; oaumaitre@ chu-clermontferrand.fr Accepted 6 September 2002

.......................

Objective: To study the levels of procalcitonin (PCT) in various inflammatory states seen in an internal medicine department and to evaluate the possible discriminative role of PCT in differentiating bacterial infection from other inflammatory processes. Methods: PCT, C reactive protein (CRP), and white blood cell count (WBC) were measured in patients admitted to the department for fever or biological inflammatory syndrome, or both. The serum of 173 consecutive patients was analysed according to the aetiological diagnosis. The patients were divided into two groups: group I (n=60) with documented bacterial or fungal infection; group II (n=113) with abacterial inflammatory disease. Results: PCT levels were >0.5 ng/ml in 39/60 (65%) patients in group I. In group II, three patients with a viral infection had slightly increased PCT levels (0.7, 0.8, and 1.1 ng/ml) as did two others, one with crystal arthritis and the other with vasculitis (0.7 ng/ml in both cases). All other patients in group II had PCT levels <0.5 ng/ml. In this study a value of PCT >0.5 ng/ml was taken as the marker of bacterial infection (sensitivity 65%, specificity 96%). PCT values were more discriminative than WBC and CRP in distinguishing a bacterial infection from another inflammatory process. Conclusion: PCT levels only rose significantly during bacterial infections. In this study PCT levels >1.2 ng/ml were always evidence of bacterial infection and the cue for starting antibiotic treatment.

rocalcitonin (PCT), the precursor of the hormone calcitonin, is produced under normal conditions in the C cells of the thyroid gland. In healthy subjects, PCT levels are <0.10 ng/ml. PCT determination was rst performed by in 1993 Assicot et al in children to differentiate bacterial from viral meningitis.1 Since that date, PCT has become a marker of bacterial infection and there is a widening range of indications for its use.2 3 Determination of the PCT level is now routinely performed in intensive care and surgery units to provide rapid evidence of bacterial origin or a shock or a respiratory distress syndrome; to differentiate pancreatitis with infected necrosis more easily from non-complicated pancreatitis; and for early detection of infectious postoperative complications.46 However, little work has been done on the usefulness of PCT in diseases other than infectious states. Thus we carried out a study of PCT in various inammatory states seen in an internal medicine department. This work aimed at evaluating the possible discriminative use of PCT in differentiating bacterial infection from other inammatory processes.

Patients who had received antibiotic treatment before admission were excluded. Only documented infections were analysed. The diagnosis of bacterial or fungal infection was only established if a pathogen was isolated in various bacterial samples (blood cultures, sputum, pus, stool, or urine) or if serum samples were positive for Chlamydia pneumoniae, Coxiella burnettii, Brucella melitensis, and Legionella pneumoniae infections. The diagnosis of viral infection was established in a patient with positive serum samples or positive polymerase chain reaction tests from cerebrospinal uid. Patients with suspected bacterial or viral infection but in whom no pathogen could be identied were excluded from the study. In the same way, in order to be in a position to explain the results of this study, patients with an inammatory syndrome without a clear cut diagnosis were excluded. Measurements PCT was measured by an immunoluminometric assay (Lumitest-PCT, Brahms-Diagnostica, Berlin, Germany). The threshold of detection of PCT dened by our laboratory is 0.1 ng/ml. Values of PCT levels >0.5 ng/ml were considered as abnormal. Statistical analysis Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 10.1 package. The values of the three variables of inammation are expressed as median and range. Because of non-normal

.............................................................

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CRP, C reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; PCT, procalcitonin; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; TNF, tumour necrosis factor ; WBC, white blood cell count

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Subjects From October 1999 to December 2001 we conducted a prospective study at the internal medicine department of the teaching hospital of Clermont-Ferrand, France. PCT serum levels were measured within 24 hours of admission in patients admitted to hospital for fever >38 and/or for an inammatory syndrome as dened by a rise in erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) according to Millers formula (normal for age: female ESR = (age + 10)/2, male ESR= age/2) and/or by C reactive protein (CRP)>20 mg/l. PCT, white blood cell count (WBC), and CRP obtained on admission were analysed according to the nal aetiological diagnosis of bacterial infection or inammatory process of a different nature.

www.annrheumdis.com

Downloaded from ard.bmj.com on July 3, 2012 - Published by group.bmj.com

338 Delvaux, Andr, Colombier, et al

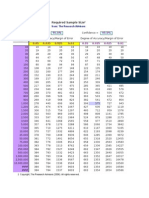

Table 1

Infections

Biological variables of group I: bacterial or fungal infections

n 13 1 13 13 9 4 1 1 4 1 White cell count Median (range) (109/l) 14.4 12.5 10.2 9.8 6.3 8.7 11.4 1.1 7.5 3.0 (5.430.1) (6.432.1) (3.632.7) (3.016.9) (6.49.0) CRP Median (range) (mg/l) 157.5 97 180 167 125 61 353 60 101 282 (22458.2) (3509) (55363) (75.1341) (34165) Procalcitonin Median (range) (ng/ml) 6.5 4.2 1 0.65 0.8 0.35 0.2 0.1 0.1 1.7 (0.6424) (0.1160.7) (0.191) (0.323.7) (0.12.5)

Bacterial infections Septicaemia Skin infection Pneumonia Pyelonephritis Diarrhoea Endocarditis Arthritis Brucellosis Tuberculosis Fungal infection Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia

distributions of the variables, we used the Mann-Whitney U test to compare the two diagnostic groups: bacterial infection and abacterial inammation. The diagnostic value of PCT and other inammatory variables for detecting bacterial infection was established by a receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC). Finally, a logistic regression was used to study the relation between the nal diagnosis and the three biological variables.

RESULTS

One hundred and seventy three consecutive patients were included (98 women, 75 men; mean age 68 years). On the basis of the nal diagnosis, two different groups were established. Group I comprised 60 patients with documented bacterial (n=59) or fungal (n=1) infection and group II 113 patients with abacterial inammation. Tables 1 and 2 show the different inammatory processes and the corresponding median values of PCT, CRP, and WBC for groups I and II. In group I, 65% of patients (39/60) with bacterial or fungal infection had PCT levels >0.5 ng/ml. Of these patients, three had autoimmune disease treated by immunosuppressive drugs (one vasculitis, one lupus, one rheumatoid arthritis), one was being treated with cyclosporin for cardiac transplant,

and one other was receiving chlorambucil for lymphoid leukaemia. All ve of these infected patients had PCT levels >0.5 ng/ml. Table 3 gives the PCT values according to the pathogen isolated. In group II, 96% of patients (108/113) with abacterial inammatory disease had PCT levels <0.5 ng/ml. Five patients had false positive results. Three patients with viral infection one with cytomegalovirus infection, one with Epstein-Barr virus, and one with Enterovirus meningitishad slightly increased PCT (0.8, 1.1, and 0.7 ng/ml, respectively). One patient with crystal arthritis and the other with digestive vasculitis had PCT levels >0.5 ng/ml (0.7 ng/ml in both cases). In this study, PCT levels >0.5 ng/ml were a marker of bacterial infection with a specicity of 96%, a sensitivity of 65%, a positive predictive value of 89%, and a negative predictive value of 84%. Area under the ROC curve for the prediction of bacterial infection was 0.84 (95% condence interval (CI), 0.76 to 0.91; p=0.0001) for PCT, 0.62 (95% CI 0.53 to 0.71; p=0.011) for WBC, and 0.73 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.80; p=0.0001) for CRP (g 1). On the ROC curve the PCT level that combined greatest sensitivity and comparatively good specicity was 0.35 ng/ml (specicity 88.5%, sensitivity 72%). Because of the distributions of inammatory variables we used the MannWhitney U test to compare the variables in the two groups. Values of WBC, CRP, and PCT were signicantly higher

Table 2

Biological variables of group II: abacterial inflammatory diseases

n 9 4 5 24 13/24 10 3 4 1 1 1 1 2 25 14 2 2 1 1 1 2 White blood count Median (range) (109/l) 5.1 (2.313.3) 12.2 (11.414.1) 10.1 (4.612.0) 9.2 (3.317.4) 9.1 (5.216.6) 9.0 (4.419.5) 9.0 (6.99.5) 5.8 (2.89.4) 9.7 6.7 6.4 4.2 9.5 (8.710.4) 7.8 (4.715.0) 10.7 (6.814.9) 6.6 (4.78.5) 7.9 (7.98.0) 5.7 6.6 5.5 7.6 CRP Median (range) (mg/l) 15.1 (1.9145) 229.5 (78313) 234 (80403) 82.05 (7.6387) 84.6 (57.4310) 48.75 (0.971.5) 6.7 (2.414) 10.95 (5.420) 40.9 8.5 68.6 32.4 178.15 (3.3353) 108.75 (4.7258) 107 (21.3274) 191 (135247) 34.15 (25.642.7) 8.8 203 99 3.5 Procalcitonin Median (range) (ng/ml) 0.2 (0.11.1) 0.1 (0.10.5) 0.3 (0.10.7) 0.1 (0.10.8) 0.1 (0.10.2) 0.1 (0.10.2) 0.2 (0.10.3) 0.1 (0.10.2) 0.2 0.4 0.2 0.1 0.2 (0.10.3) 0.2 (0.10.5) 0.1 (0.10.4) 0.15(0.10.2) 0.1 0.5 0.2 0.2 0.1

Inflammatory diseases Viral infections Stills disease Crystal arthritis Vasculitis Giant cell arteritis Ulcerative colitis Sarcoidosis Connective tissue disease TRAPS Amyloidosis BOOP Weber Christian disease Relapsing polychondritis Neoplasm Pulmonary embolism/phlebitis Thyroiditis Haematoma Farmers lung Chronic aortic dissection Osteoporotic fracture Drug fever

TRAPS, TNF receptor associated periodic syndrome; BOOP, Bronchiolitis obliterans organising pneumonia.

www.annrheumdis.com

Downloaded from ard.bmj.com on July 3, 2012 - Published by group.bmj.com

Bacterial infection and other inflammatory processes 339

Table 3

PCT levels according to pathogen isolated

n 2 2 1 1 2 6 4 1 17 1 1 1 1 1 7 6 1 4 1 PCT (ng/ml) 80.4 (0.5160.7) 23.7 (0.423.7) 15.2 6.5 6.45(0.112.8) 2.45(0.130.4) 2 (0.14.2) 1.9 1.9 (0.1458.2) 1.7 1.6 1 0.9 0.9 0.8 (0.273.7) 0.35(0.12.5) 0.2 0.1 0.1

Bacterial organism isolated Chlamydia Clostridium difficile Legionella Morganella morganii Haemophilus influenzae Streptococcus pneumoniae Staphylococcus aureus Klebsiella oxytoca Escherichia coli Pneumocystis carinii Leptospira Pseudomonas aeroginosa Coxiella burnettii Citrobacter freundeii Salmonella Streptococcus non-pneumoniae Campylobacter Mycobacterium hominis Brucella

Figure 1 Prediction of bacterial infection ROC curves, with area under curve for procalcitonin=0.84, WBC=0.618, CRP=0.729.

(p=0.011; p=0.0001; and p=0.0001, respectively) in group I (WBC: median 10.0109/l, range (3.032.7)109/l; CRP: median 137 mg/l, range 3509; PCT: median 0.9 ng/ml, range 0.1458 ) compared with group II (WBC: median 8.1109/l, range (2.320.6)109/l; CRP: median 71.5 mg/l, range 0.9403; PCT: median 0.1, range 0.11.1). A logistic regression was performed to determine the relation between the three biological variables and the two diagnostic groups, with the group as the character to be explained and WBC, CRP, and PCT as the explanatory variables. In our series, 84% of the patients were correctly classied by the regression. The variable in the equation was PCT with a signicance of 0.001 (WBC: p=0.250; CRP: p=0.487) (Hosmer-Lemeshows test: 2=0.99; p=0.91).

DISCUSSION

It has been shown that PCT has a good specicity and a good positive predictive value for systemic bacterial infection. With a cut off level for PCT of >0.5 ng/ml for diagnosis of bacterial infection, only ve patients in our series (three with viral infections, one with crystal arthritis, and one with vasculitis)

had false positive results. In previously published reports, the cut off level beyond which a bacterial infection is considered as denite ranges between 1 and 2 ng/ml, except in patients receiving OKT3, in whom PCT levels are increased without infection.3 7 8 Hence, in our series, for PCT levels >1.2 ng/ml, there were no false positive results. It is the level we routinely use as a reference value once biological investigations have been done and before empirical antibiotic treatment is started. The specicity (96%) and the sensitivity (65%) of PCT in our series, for PCT levels >0.5 ng/ml, are comparable with those reported elsewhere.3 8 False negative results may occur. PCT is not raised in localised bacterial infections. The nature of the causative infectious agent also inuences the rise in PCT levels. In a human experimental study, PCT levels were raised after injection of bacterial endotoxin. The rise in PCT was preceded by raised cytokine tumour necrosis factor (TNF), suggesting a role of TNF in PCT secretion. Furthermore, it is during infections associated with marked TNF release, such as Gram-negative infections and malaria, that the highest PCT levels are seen.9 10 In malaria, PCT levels may rise to 1000 times the normal value. Infections in which other inammatory pathways are activated do not increase PCT levels. This observation has been well documented in tuberculosis, as in our four patients with proven evidence of the disease.11 In addition, PCT levels do not increase in Lyme disease or mycobacterial infections.3 12 In our series, two patients who had endocarditis, one due to Streptococcus anginosus and the other to Staphylococcus aureus, had normal PCT levels. Lastly, the short half life (22 hours) of the PCT may explain why PCT levels recorded shortly after the beginning of antibiotic treatment are sometimes normal.2 Except in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody associated vasculitis and connective tissue disease, PCT levels have not been studied during abacterial inammatory processes.13 14 In the patients studied, PCT levels, unlike those of CRP, stayed normal or increased only slightly, thereby making it possible to differentiate between a are of the inammatory disease and systemic bacterial infection. In Wegeners granulomatosis, a moderate increase in PCT levels was seen in the very active forms.15 Hence, it is recommended that PCT levels >1 ng/ml should be used to distinguish between a are vasculitis and bacterial infection.16 None of our ve patients with are Wegeners granulomatosis had an increase in PCT levels. There is little published information on PCT levels in other autoimmune diseases and inammatory processes. Because of the additional cost, the usefulness of measuring PCT levels in proven cases of bacterial infection is a matter of debate. However, PCT can be useful to differentiate between bacterial infection and other inammatory processes in patients who have a rise in classic inammatory markers without isolation of an infectious agent in the biological samples. Giant cell arteritis presenting as isolated fever, crystal arthritis, and Stills disease are disorders that are sometimes difcult to distinguish from true bacterial infection. In these three diseases, as seen in ndings from our patients, there is a marked inammatory syndrome (median values of CRP and WBC respectively 84.6 mg/l and 9.1109/l, 234 mg/l and 10.1109/l, 229.5 mg/l and 12.2109/l). These inammatory variables were similar to those of the patients with septicaemia or skin infection or pneumonia (table 1). In contrast, PCT levels were greatly different between the two groups. Median values of PCT were always <0.5 ng/ml in patients with abacterial inammatory disease, whereas values of PCT were 6.5 ng/ml in septicaemia, 4.2 ng/ml in skin infection, and 1 ng/ml in pneumonia. Likewise, median values of CRP and WBC were high in the neoplasm group and in patients with pulmonary embolism, whereas the median value of PCT was <0.5 ng/ml. It seems, therefore, that normal PCT levels during severe inammatory disease argue in favour of an abacterial cause of the disorder. In contrast, during inammatory processes in which CRP levels and WBC are raised less (as in our patients

www.annrheumdis.com

Downloaded from ard.bmj.com on July 3, 2012 - Published by group.bmj.com

340 Delvaux, Andr, Colombier, et al

with vasculitis or ulcerative colitis, who had inammatory variables comparable with those of patients with endocarditis), normal PCT levels are not a sufcient cause for ruling out localised bacterial infection or Gram positive infection. PCT levels were always raised in the ve patients with bacterial infection receiving immunosuppressive treatment. One patient had septicaemia, one had skin infection, one had diarrhoea and two others had pneumonia. All ve patients had fever and raised inammatory variables, which were evocative of an inammatory disease are and infectious complication. We started antibiotic treatment in all cases before the results of bacterial studies establishing the bacterial or fungal origin of the fever were obtained. PCT can also help in detecting bacterial infection during febrile or inammatory periods in patients with previous inammatory disease even when they are receiving immunosuppressive treatment. This nding is unsurprising because increased PCT levels have been found in patients with neutropenic fever and bacterial infection.17 Although the site of procalcitonin production during sepsis is uncertain, it does not seem to be in the leucocytes. PCT levels only rose signicantly during systemic bacterial or fungal infection. In patients with fever or inammatory syndrome who have PCT levels >1.2 ng/ml, we consider that bacterial infection should be sought and antibiotic treatment started even before the results of the bacteriological investigations are obtained. This approach is even more strongly recommended in patients with inammatory disease given immunosuppressive treatment. In contrast, once tuberculosis and mycobacterial infection have been ruled out, normal PCT levels do not argue in favour of bacterial infection.

REFERENCES

1 Assicot M, Gendrel D, Carsin H, Raymond J, Guilbaud J, Bohuon C. High serum procalcitonin concentrations in patients with sepsis and infection. Lancet 1993;341:51518. 2 Ferriere F. Intrt de la procalcitonine, nouveau marqueur de linfection bactrienne. Ann Biol Clin 2000;58:4959. 3 Schwarz S, Bertram M, Schwab S, Andrassy C, Hacke W. Serum procalcitonin levels in bacterial and abacterial meningitis. Crit Care Med 2000;28:182832. 4 De Werra I, Jaccard C, Corradin SB, Chiolero R, Yersin B, Gallati H, et al. Cytokines nitrite/nitrate, soluble tumor necrosis factor receptors, and procalcitonin concentrations: comparisons in patients with septic shock, cardiogenic shock, and bacterial pneumonia. Crit Care Med 1997;25:60713. 5 Rau B, Steinbach G, Gansauge F, Grnert A, Beger HG. The potential role of procalcitonin and interleukin 8 in the prediction of infected necrosis inacute pancreatitis. Gut 1997;41:832-40. 6 Reith HB, Mittelktter U, Debus ES, Kussner C, Thiede A. Procalcitonin in early detection of post operative complications. Dig Surg 1998;15:2605. 7 Sabat R, Hflich C, Dcke WD, Oppert M, Kern F, Windrich B, et al. Massive elevation of procalcitonin plasma levels in the absence of infection in kidney transplant patients treated with pan-T-cell antibodies. Intensive Care Med 2001;27:98791. 8 Reinhart K, Karzai W, Meisner M. Procalcitonin as a marker of the sytemic inflammatory response to infection. Intensive Care Med 2000;26:1193200. 9 Smith MD, Suputtamongkol Y, Chaowagul W. Elevated serum procalcitonin levels in patients with melioidosis. J Infect Dis 1995;20:6415. 10 Richard-Lenoble D, Duong TH, Ferrer A, Lacombe C, Assicot M, Gendrel D, et al. Changes in procalcitonin and interleukin-6 levels among treated African patients with different clinical forms of malaria. Trans Roy Soc Trop Med Hyg 1997;91:3056. 11 Zarka V, Valat C, Lemari E, Boissinot E, Carr Ph, Besnard JC, et al. Procalcitonine srique et pathologie infectieuse respiratoire. Rev Pneumol Clin 1999;6:3659. 12 Gerard Y, Hober D, Assicot M , Alfandari S, Ajana F, Bourez JM, et al. Procalcitonin as a marker of bacterial sepsis in patients infected with HIV-1. J Infect 1997;35:416. 13 Eberhard OK, Haubitz M, Brunkhorst FM, Kliem V, Koch KM, Brunkhorst R. Usefulness of procalcitonin for differentiation between activity of systemic autoimmune disease (systemic lupus erythematosus/systemic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis) and invasive bacterial infection. Arthritis Rheum 1997;40:12506. 14 Shin KC, Lee YJ, Kang SW, Baek HJ, Lee EB, Kim HA, et al. Serum procalcitonin measurement for detection of intercurrent infection in febrile patient with SLE. Ann Rheum Dis 2001;60:9889. 15 Moosig F, Csernok E, Reinhold-Keller E, Schmitt W, Gross WL. Elevated procalcitonin levels in active Wegeners granulomatosis. J Rheumatol 1998;25:15313. 16 Schwenger V, Sis J, Breitbart A, Andrassy K. CRP levels in autoimmune disease can be specified by measurement of procalcitonin. Infection 1998;26:2746. 17 Bernard L, Ferriere F, Canassus P, Malas F, Leveque S, Guillevin L, et al. Procalcitonin as an early marker of bacterial infection in severely neutropenic febrile adults. Clin Infect Dis 1998;27:9145.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We thank Jeffrey Watts for help with the English version of the manuscript. .....................

Authors affiliations

I Delvaux, M Andr, F Meylheuc, O Aumatre, Department of Internal Medicine, Gabriel Montpied Hospital, groupe hospitalier Saint-Jacques, BP 69, 63003 Clermont-Ferrand Cedex 1, France M Colombier, R-J Bgue, Laboratory of Hormonology, Gabriel Montpied Hospital, groupe hospitalier Saint-Jacques, BP 69, 63003 Clermont-Ferrand Cedex 1, France E Albuisson, Laboratory of Biostatistic, Gabriel Montpied Hospital, groupe hospitalier Saint-Jacques, BP 69, 63003 Clermont-Ferrand Cedex 1, France J-C Piette, Department of Internal Medicine, Piti-Salptrire Hospital, 4783 boulevard de lHpital, 75651 Paris Cedex 13, France

www.annrheumdis.com

Downloaded from ard.bmj.com on July 3, 2012 - Published by group.bmj.com

Can procalcitonin measurement help in differentiating between bacterial infection and other kinds of inflammatory processes?

I Delvaux, M Andr, M Colombier, et al. Ann Rheum Dis 2003 62: 337-340

doi: 10.1136/ard.62.4.337

Updated information and services can be found at:

http://ard.bmj.com/content/62/4/337.full.html

These include:

References

This article cites 16 articles, 3 of which can be accessed free at:

http://ard.bmj.com/content/62/4/337.full.html#ref-list-1

Article cited in:

http://ard.bmj.com/content/62/4/337.full.html#related-urls

Email alerting service

Receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up in the box at the top right corner of the online article.

Topic Collections

Articles on similar topics can be found in the following collections Degenerative joint disease (3019 articles) Musculoskeletal syndromes (3249 articles) Vascularitis (225 articles)

Notes

To request permissions go to:

http://group.bmj.com/group/rights-licensing/permissions

To order reprints go to:

http://journals.bmj.com/cgi/reprintform

To subscribe to BMJ go to:

http://group.bmj.com/subscribe/

You might also like

- Ability of Procalcitonin To Predict Bacterial MeningitisDocument20 pagesAbility of Procalcitonin To Predict Bacterial MeningitisGeorge WinchesterNo ratings yet

- PCT FeverDocument6 pagesPCT FeverAndi BintangNo ratings yet

- Emergencias-2012 24 5 348-356 EngDocument9 pagesEmergencias-2012 24 5 348-356 EngJarvis WheelerNo ratings yet

- Procalcitonin Levels Diagnose Systemic Infections in ED PatientsDocument7 pagesProcalcitonin Levels Diagnose Systemic Infections in ED PatientsAndi BintangNo ratings yet

- Serum Procalcitonin in Bacterial & Non-Bacterial Meningitis in ChildrenDocument5 pagesSerum Procalcitonin in Bacterial & Non-Bacterial Meningitis in ChildrenrayhantaswinNo ratings yet

- White Paper CPD Sepsis AJCP 2005Document5 pagesWhite Paper CPD Sepsis AJCP 2005jtmchughNo ratings yet

- The Use of Procalcitonin As A Marker of Sepsis in Children: Abst TDocument3 pagesThe Use of Procalcitonin As A Marker of Sepsis in Children: Abst TAsri RachmawatiNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Value of CSF C-Reactive Protein in Meningitis: A Prospective StudyDocument4 pagesDiagnostic Value of CSF C-Reactive Protein in Meningitis: A Prospective StudyHabibur RahmanNo ratings yet

- 58 JMSCRDocument4 pages58 JMSCRhumayun kabirNo ratings yet

- Serum Procalcitonin Levels in Bacterial and Abacterial MeningitisDocument5 pagesSerum Procalcitonin Levels in Bacterial and Abacterial MeningitisSaul Gonzalez HernandezNo ratings yet

- 2165-Article Text-2597-1-10-20200105Document7 pages2165-Article Text-2597-1-10-20200105IKA 79No ratings yet

- Marcadores Sericos para Cole AgudaDocument6 pagesMarcadores Sericos para Cole Agudajessica MárquezNo ratings yet

- Xia 2016Document29 pagesXia 2016Dewi PrasetiaNo ratings yet

- Validity of CSF Tests for Diagnosing Tuberculous MeningitisDocument5 pagesValidity of CSF Tests for Diagnosing Tuberculous MeningitismelisaberlianNo ratings yet

- PCT 2006 Read For DiscussionDocument8 pagesPCT 2006 Read For DiscussionArnavjyoti DasNo ratings yet

- 2 - Adult Meningitis in A Setting of High HIV and TB Prevalence - Findings From 4961 Suspected Cases 2010 (Modelo para o Trabalho)Document6 pages2 - Adult Meningitis in A Setting of High HIV and TB Prevalence - Findings From 4961 Suspected Cases 2010 (Modelo para o Trabalho)SERGIO LOBATO FRANÇANo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Accuracy of Procalcitonin, Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio, C-Reactive Protein, and Lactate in Suspected Bacterial SepsisDocument25 pagesDiagnostic Accuracy of Procalcitonin, Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio, C-Reactive Protein, and Lactate in Suspected Bacterial SepsisMelissa Indah SariNo ratings yet

- Procalcitonin and C-Reactive Protein During Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome, Sepsis and Organ DysfunctionDocument9 pagesProcalcitonin and C-Reactive Protein During Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome, Sepsis and Organ DysfunctionAsri RachmawatiNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of PCV, Cd4 T Cell Counts, ESR and WBC Counts in Malaria Infected Symptomatic HIV (Stage 11) Male HIV/ Aids Subjects On Antiretroviral Therapy (Art) in Nnewi, South Eastern NigeriaDocument5 pagesEvaluation of PCV, Cd4 T Cell Counts, ESR and WBC Counts in Malaria Infected Symptomatic HIV (Stage 11) Male HIV/ Aids Subjects On Antiretroviral Therapy (Art) in Nnewi, South Eastern NigeriaIOSR Journal of PharmacyNo ratings yet

- Carraro 2013 RSBMTV 46 N 2 P 161Document5 pagesCarraro 2013 RSBMTV 46 N 2 P 161Emerson CarraroNo ratings yet

- Pone 0062323Document10 pagesPone 0062323Malik IbrahimNo ratings yet

- G G Scholar: Pubmed CentralDocument6 pagesG G Scholar: Pubmed CentralIkhsan FebriansyahNo ratings yet

- Attenuation of Sepsis-Related Immunoparalysis by Continuous Veno-Venous Hemofiltration in Experimental Porcine PancreatitisDocument8 pagesAttenuation of Sepsis-Related Immunoparalysis by Continuous Veno-Venous Hemofiltration in Experimental Porcine PancreatitismanuelantoniomenaNo ratings yet

- RT Real-Time PCR Detection of HRVDocument8 pagesRT Real-Time PCR Detection of HRVNashiely RdzNo ratings yet

- Onco 1559mDocument7 pagesOnco 1559mOkki Masitah Syahfitri NasutionNo ratings yet

- Increased Expressions of Integrin Subunit β1, β2 and β3 in Patients with Acute InfectionDocument5 pagesIncreased Expressions of Integrin Subunit β1, β2 and β3 in Patients with Acute InfectionClaudia JessicaNo ratings yet

- Vidas Brahms PCT Procalcitonin Brochure 1Document4 pagesVidas Brahms PCT Procalcitonin Brochure 1swbartlinNo ratings yet

- C-Reactive Protein, Severity of Pneumonia and Mortality in Elderly, Hospitalised Patients With Community-Acquired PneumoniaDocument5 pagesC-Reactive Protein, Severity of Pneumonia and Mortality in Elderly, Hospitalised Patients With Community-Acquired PneumoniaLoserlikemeNo ratings yet

- Septic MarkerDocument10 pagesSeptic MarkerDesti NurulNo ratings yet

- Utility of Cytometric Parameters and Indices As Predictors of Mortality in Patients With SepsisDocument6 pagesUtility of Cytometric Parameters and Indices As Predictors of Mortality in Patients With SepsisPablo VélezNo ratings yet

- J Clin Virol 2020Document4 pagesJ Clin Virol 2020Alejandro Jiménez BlasNo ratings yet

- Cytometry Part B Clinical - 2018 - Garcia Prat - Extended Immunophenotyping Reference Values in A Healthy PediatricDocument11 pagesCytometry Part B Clinical - 2018 - Garcia Prat - Extended Immunophenotyping Reference Values in A Healthy PediatricSabina-Gabriela MihaiNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Serum Levels of Interleukins 6, 8, 17 and 22 in Acne Vulgaris - A Cross-Sectional Study - PMCDocument10 pagesEvaluation of Serum Levels of Interleukins 6, 8, 17 and 22 in Acne Vulgaris - A Cross-Sectional Study - PMCtisadermaNo ratings yet

- CC 12918Document59 pagesCC 12918Romica MarcanNo ratings yet

- Img#Document5 pagesImg#AngelNo ratings yet

- Chaves 2005 PDFDocument5 pagesChaves 2005 PDFWa Nur Arlin RahmadhantyNo ratings yet

- Early Diagnosis of Sepsis Using Serum Bio MarkersDocument5 pagesEarly Diagnosis of Sepsis Using Serum Bio Markersalemarques16No ratings yet

- Ijpedi2021 1544553Document6 pagesIjpedi2021 1544553Naresh ReddyNo ratings yet

- Carey 2005 CD4 Quantitation HIV + Child Antiretroviral TXDocument4 pagesCarey 2005 CD4 Quantitation HIV + Child Antiretroviral TXMaya RustamNo ratings yet

- Wood-2016-Cytometry Part B: Clinical CytometryDocument7 pagesWood-2016-Cytometry Part B: Clinical CytometryWalter Jhon Delgadillo AroneNo ratings yet

- Predictors of Spontaneous Bleeding in DengueDocument4 pagesPredictors of Spontaneous Bleeding in DengueSawettachai JaitaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Features and CD4+ T Cells Count in AIDS Patients With CMV Retinitis - Correlation With MortalityDocument6 pagesClinical Features and CD4+ T Cells Count in AIDS Patients With CMV Retinitis - Correlation With MortalitysyenadamaraNo ratings yet

- Interpreting PCR Results: Distinguishing Old From Recent COVID-19 InfectionsDocument5 pagesInterpreting PCR Results: Distinguishing Old From Recent COVID-19 InfectionsHitesh MutrejaNo ratings yet

- Simon 2004Document12 pagesSimon 2004mr_curiousityNo ratings yet

- Automated Immature Granulocyte Count in Patients of An Intensive Care Unit With Suspected InfectionDocument7 pagesAutomated Immature Granulocyte Count in Patients of An Intensive Care Unit With Suspected InfectionnissashiblyNo ratings yet

- Cellular immune response to SARS-CoV-2 in uninfected healthcare workersDocument14 pagesCellular immune response to SARS-CoV-2 in uninfected healthcare workersAlexis Guevara QuijadaNo ratings yet

- Kol Ditz 2016Document3 pagesKol Ditz 2016Lanna HarumiyaNo ratings yet

- Enteroviral Meningoencephalitis Case SeriesDocument4 pagesEnteroviral Meningoencephalitis Case SeriesRonald Ivan WijayaNo ratings yet

- Imp bn1Document5 pagesImp bn1Karito FloresNo ratings yet

- Journal SDocument6 pagesJournal SLyla SandyNo ratings yet

- Serum Procalcitonin For Differentiating Bacterial Infection From Disease Flares in Patients With Systemic Lupus ErythematosusDocument29 pagesSerum Procalcitonin For Differentiating Bacterial Infection From Disease Flares in Patients With Systemic Lupus ErythematosusHadi SusilaNo ratings yet

- PCT biomarker accurately diagnoses pediatric appendicitisDocument6 pagesPCT biomarker accurately diagnoses pediatric appendicitisGilang IrwansyahNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis of C.difficile v7.1 + Table and FiguresDocument12 pagesDiagnosis of C.difficile v7.1 + Table and FiguresJuan RecioNo ratings yet

- Plasma Cytokine Profile On Admission Related To Aetiology in Community Acquired PneumoniaDocument9 pagesPlasma Cytokine Profile On Admission Related To Aetiology in Community Acquired Pneumoniahusni gunawanNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Value of Procalcitonin For Acute Complicated AppendicitisDocument10 pagesDiagnostic Value of Procalcitonin For Acute Complicated AppendicitisAnonymous 4K2TOtpfNo ratings yet

- Consideration of Some Other Specific Indications: BacteremiaDocument18 pagesConsideration of Some Other Specific Indications: BacteremiaMOHAMMAD JOFA RACHMAN PUTERANo ratings yet

- 05 Investigations For PneumoniaDocument4 pages05 Investigations For Pneumoniause4meNo ratings yet

- Analytical Evaluation of a Procalcitonin ImmunoassayDocument5 pagesAnalytical Evaluation of a Procalcitonin ImmunoassayneofherNo ratings yet

- Medical Hypotheses: Yixian Li, Juan Zhou, Ian Burkovskiy, Pollen Yeung, Christian Lehmann TDocument3 pagesMedical Hypotheses: Yixian Li, Juan Zhou, Ian Burkovskiy, Pollen Yeung, Christian Lehmann TAndi BintangNo ratings yet

- Subarachnoid Block For Caesarean Section in Severe PreeclampsiaDocument6 pagesSubarachnoid Block For Caesarean Section in Severe PreeclampsiaAndi BintangNo ratings yet

- Procalcitonin As A Biomarker of Severity Degree in Sepsis Due To PneumoniaDocument5 pagesProcalcitonin As A Biomarker of Severity Degree in Sepsis Due To PneumoniaAndi BintangNo ratings yet

- Required Sample Size: From: The Research AdvisorsDocument3 pagesRequired Sample Size: From: The Research AdvisorsAbhishek Sharma100% (1)

- Anestesia General para Césarea PDFDocument7 pagesAnestesia General para Césarea PDFAgnese ValentiniNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1052305714000561 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S1052305714000561 MainAndi BintangNo ratings yet

- Bar A Zanchi 2018Document17 pagesBar A Zanchi 2018Andi BintangNo ratings yet

- Parthasarathy2013 PDFDocument7 pagesParthasarathy2013 PDFAndi BintangNo ratings yet

- Anestesia General para Césarea PDFDocument7 pagesAnestesia General para Césarea PDFAgnese ValentiniNo ratings yet

- Cultural Sociology of Mental Illness n28Document5 pagesCultural Sociology of Mental Illness n28Andi BintangNo ratings yet

- Depresión e InmunidadDocument13 pagesDepresión e InmunidadgabisaenaNo ratings yet

- Overweight linked to increased risk of lower back painDocument8 pagesOverweight linked to increased risk of lower back painAndi BintangNo ratings yet

- Sacral Nerve Stimulation Reduces Elevated Urinary Nerve Growth Factor Levels in Women With Symptomatic Detrusor OveractivityDocument5 pagesSacral Nerve Stimulation Reduces Elevated Urinary Nerve Growth Factor Levels in Women With Symptomatic Detrusor OveractivityAndi BintangNo ratings yet

- Instruction For Author ClimactericDocument9 pagesInstruction For Author ClimactericAndi BintangNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0002937800704534 Main PDFDocument1 page1 s2.0 S0002937800704534 Main PDFAndi BintangNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0002937803001388 MainDocument3 pages1 s2.0 S0002937803001388 MainAndi BintangNo ratings yet

- 2013 Student Membership ApplicationDocument1 page2013 Student Membership ApplicationAndi BintangNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0002937803001388 MainDocument3 pages1 s2.0 S0002937803001388 MainAndi BintangNo ratings yet

- Association Between Constipation and Colorectal Cancer Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational StusdgdiesDocument10 pagesAssociation Between Constipation and Colorectal Cancer Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational StusdgdiesAndi BintangNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Diabetes and Impaired Fasting Glucose in Adults in The U.S. PopulationDocument6 pagesPrevalence of Diabetes and Impaired Fasting Glucose in Adults in The U.S. PopulationAndi BintangNo ratings yet

- Anthropometry: Ergonomics Additional ResourcesDocument5 pagesAnthropometry: Ergonomics Additional ResourcesAndi BintangNo ratings yet

- Hepatitis C APASLfghDocument27 pagesHepatitis C APASLfghAndi BintangNo ratings yet

- MK Giz Slide Infant Feeding PracticeDocument1 pageMK Giz Slide Infant Feeding PracticeAndi BintangNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0021755713002003 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S0021755713002003 MainAndi BintangNo ratings yet

- Urologi PDFDocument237 pagesUrologi PDFAndi BintangNo ratings yet

- Cap Bts 2009 ComplitdgDocument139 pagesCap Bts 2009 ComplitdgAndi BintangNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0021755713002003 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S0021755713002003 MainAndi BintangNo ratings yet

- Serviks DocjhjuDocument366 pagesServiks DocjhjuAndi BintangNo ratings yet

- PCT CAP ABiuytoDocument10 pagesPCT CAP ABiuytoAndi BintangNo ratings yet

- ATS Guidelines CAP ManagementDocument25 pagesATS Guidelines CAP ManagementMae Matira AbeladorNo ratings yet

- Vol3issue12018 PDFDocument58 pagesVol3issue12018 PDFpyrockerNo ratings yet

- Methodological Literature Review 1 1Document8 pagesMethodological Literature Review 1 1api-584018105No ratings yet

- Intro To Wastewater Collection and PumpingDocument84 pagesIntro To Wastewater Collection and PumpingMoh'd KhadNo ratings yet

- عقد خدمDocument2 pagesعقد خدمtasheelonlineNo ratings yet

- The Precious Little Black Book DownloadDocument226 pagesThe Precious Little Black Book DownloadAsanda YekiNo ratings yet

- Care Plan SummaryDocument5 pagesCare Plan Summaryapi-541785084No ratings yet

- Hvis Msds PDFDocument6 pagesHvis Msds PDFsesbasar sitohangNo ratings yet

- 1.2.1 Log 1Document3 pages1.2.1 Log 1linuspauling101100% (6)

- STP 1560-2013Document346 pagesSTP 1560-2013HieuHTNo ratings yet

- Maintenance Scheduling For Electrical EquipmentDocument82 pagesMaintenance Scheduling For Electrical Equipmentduonza100% (6)

- Prepositions of Time ExplainedDocument18 pagesPrepositions of Time ExplainedyuèNo ratings yet

- NurseCorps Part 8Document24 pagesNurseCorps Part 8smith.kevin1420344No ratings yet

- 11 - Comfort, Rest and Sleep Copy 6Document28 pages11 - Comfort, Rest and Sleep Copy 6Abdallah AlasalNo ratings yet

- OPD Network ListDocument354 pagesOPD Network ListSHAIKH ABDUL AZIZ salim bashaNo ratings yet

- Voyeuristic Disorder SymptomsDocument7 pagesVoyeuristic Disorder SymptomsgoyaNo ratings yet

- Nursing Assignment SampleDocument12 pagesNursing Assignment Sampleswetha swethaNo ratings yet

- Legal Medicine 2020 2021Document4 pagesLegal Medicine 2020 2021Zie DammiNo ratings yet

- Posters Whofic 2020Document107 pagesPosters Whofic 2020Kristel HurtadoNo ratings yet

- UV-VIS Method for Estimating Fat-Soluble Vitamins in MultivitaminsDocument6 pagesUV-VIS Method for Estimating Fat-Soluble Vitamins in MultivitaminsTisenda TimiselaNo ratings yet

- Research Paper About EpilepsyDocument4 pagesResearch Paper About EpilepsyHazel Anne Joyce Antonio100% (1)

- RNTCP - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument5 pagesRNTCP - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaakurilNo ratings yet

- Safety Reports Series No. 13 (Radiation Protection and Safety in Industrial Radiography)Document69 pagesSafety Reports Series No. 13 (Radiation Protection and Safety in Industrial Radiography)jalsadidiNo ratings yet

- Boy Scouts Lipa City Investiture CampDocument1 pageBoy Scouts Lipa City Investiture CampAndro Brendo VillapandoNo ratings yet

- Psychological Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic in The Philippines PDFDocument13 pagesPsychological Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic in The Philippines PDFAndrea KamilleNo ratings yet

- Paul B. Bishop, DC, MD, PHD, Jeffrey A. Quon, DC, PHD, FCCSC, Charles G. Fisher, MD, MHSC, FRCSC, Marcel F.S. Dvorak, MD, FRCSCDocument10 pagesPaul B. Bishop, DC, MD, PHD, Jeffrey A. Quon, DC, PHD, FCCSC, Charles G. Fisher, MD, MHSC, FRCSC, Marcel F.S. Dvorak, MD, FRCSCorlando moraNo ratings yet

- The Cell Cycle and Cancer WorksheetDocument3 pagesThe Cell Cycle and Cancer WorksheetAngie Pyatt KarrakerNo ratings yet

- Q1. Read The Passage Given Below and Answer The Questions That FollowDocument2 pagesQ1. Read The Passage Given Below and Answer The Questions That FollowUdikshaNo ratings yet

- SC 2Document2 pagesSC 2Ryan DelaCourt0% (3)

- 1866 PSC Iasc Ref Guidance t2 DigitalDocument11 pages1866 PSC Iasc Ref Guidance t2 DigitalDama BothNo ratings yet

- Thesis-Android-Based Health-Care Management System: July 2016Document66 pagesThesis-Android-Based Health-Care Management System: July 2016Noor Md GolamNo ratings yet

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (13)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityFrom EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsFrom EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionFrom EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (402)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeNo ratings yet

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (78)

- Techniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementFrom EverandTechniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (40)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsFrom EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (169)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossFrom EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- The Ultimate Guide To Memory Improvement TechniquesFrom EverandThe Ultimate Guide To Memory Improvement TechniquesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (34)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessFrom EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (327)

- The Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsFrom EverandThe Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsNo ratings yet

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingFrom EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeFrom EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (253)

- The Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingFrom EverandThe Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (41)

- The Stress-Proof Brain: Master Your Emotional Response to Stress Using Mindfulness and NeuroplasticityFrom EverandThe Stress-Proof Brain: Master Your Emotional Response to Stress Using Mindfulness and NeuroplasticityRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (109)

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingFrom EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (33)

- The Tennis Partner: A Doctor's Story of Friendship and LossFrom EverandThe Tennis Partner: A Doctor's Story of Friendship and LossRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaFrom EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Summary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (8)