Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Oaks - The Developing Male Voice

Uploaded by

Beth LiptonOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Oaks - The Developing Male Voice

Uploaded by

Beth LiptonCopyright:

Available Formats

The Developing Male Voice: Instilling Confidence in the Young Male Singer

by Vincent Oakes, Chattanooga Boys Choir

he qualities often associated with boychoirs and the sound of a young boys singing voice are ones of beauty, transcendence, and etherealism. The timbre of a confident boy singer possesses both innocence and mastery, because he must demonstrate confident use of a very delicate instrument, often against a backdrop of significant musical maturity. Conversely, when describing the tone of a mature male voice or mens chorus, the adjectives that come to mind are also typically quite desirablestrong, full, rich, and vibrant. College glee clubs, barbershop choruses, and the popularity of groups like Cantus, Chanticleer, and the Kings Singers contribute to the sense of rich sonorities we associate with mature male singers. While the relationship between these two may not be immediately recognized in terms of range, standards, timbres, or repertoire, both are treasured mediums of musical expression. However, attention must be paid to the connection between them, especially for those boys who are beginning, working through, or mastering the transition. As choral directors, we know that the journey from the unchanged to changed voice is filled with all sorts of traps, turns, and curves that prove quite difficult in the choral rehearsal setting. More importantly, the way in which we deal with these difficultiesboth real and those perceived by the choristercan have an impact and long-lasting effect on the confidence, emotions, and vocal health of young males whose psyches are almost as delicate and unpredictable as their changing voices. It is generally agreed that the antiquated method of telling boys to stop singing at the voice break, only to pick it up again once his voice has finished changing, is an outdated way of avoiding a problem rather than working through it. Though this approach does keep some ties to avoiding laryngeal or other physiological problems, we are now well-equipped to help our boys through this stage, if we can keep their confidence high through these uncertain times. Moreover, if we can equip these boys to sing through the voice change in a healthful way, we will be preparing them to enjoy a lifelong pursuit of healthy singing. Standard texts in the field now devote entire chapters to the adolescent voice and often, more specifically, the changing male voice. The writings of Duncan McKenzie1, Don Collins2, and John Cooksey3 have provided a solid foundation to help choir directors navigate the concerns surrounding the changing voice. More recent scholarship has imparted an explosion of resources for these choristers, from Ingo Titzes accessible explorations of vocal anatomy and physiology4 to Terry Barhams collection5 of approaches and rehearsal techniques for this age group. Publishers such as Cambiata Press and Bri-Lee Music have specialized in compositions and arrangements that suit the limited ranges, vocal registrations, and voice classifications of these singers. Despite this wealth of informative resources, the positive inclusion and development of male singers through the adolescent voice change continues to be a struggle for many choral directors. While choices in literature, pedagogy, voice classification, and other related musical factors may continue to make this fuzzy picture come into focus, it is the confidence of each individual singer which must be carefully considered and consistently encouraged. This large topic has been compartmentalized into four areas (discussed below) in which encouragement from the director should be maintained in order to instill an intrinsic confidence in young male singers. These categories are not only for the choral director to remain sensitive to, but also for each singer to absorb and make his own, so that he can measure his progress in each area, and enjoy its resulting success. This is all done with an aim to keep boys singing through the voice change and contributing to the health and success of their choral ensembles. Confidence in the Individual Nature of the Voice Change The voice change can pose a dramatic obstacle not only in a boys singing habits, but also in his social perception and his formative identity. The underlying principle in dealing with this vocal transition is to make sure boys understand that the voice change is a process, and not an instance.

For some, noticeable changes can be detected at ten years old, while some twelve year olds may not yet exhibit any discernable change in speaking or singing ranges6. Additionally, these changes might be present in a boys speaking voice, but he does not yet demonstrate a significant change in the singing voice. Though it may seem like it for some boys, the voice does not change overnight, and the process that all males go through is different and unique for each individual. In addition to the starting age being different, the length of each stage of the voice change, or the rate of progression through the process, also varies from one individual to the next. Just as it is natural to measure a boys maturity by his physical development, so too are comparisons formed based on speaking and singing ranges. The pressure of an adolescent male to be the tallest, the fastest, the smartest, or the most popular is predicated on being viewed as older or more mature. Likewise, just as a boy tries to demonstrate a false sense of maturity by seeming taller or more developed physically, he might also try to sound older by falsely speaking low, pushing too much of the heavier chest voice into higher parts of his range, or outright refusing to sing in what is a perfectly accessible upper part of his range. It is unhealthy for a boy to sing or consistently speak in this manner, and so we must build up each boys confidence in his natural maturation process. On this topic, John Kincaid of Simmons Middle School (AL) writes: Without the proper encouragement at his stage, many boys (and some teachers) may decide that they cant sing or are tone deaf, and end their involvement in music. What are some things that we can do to help our young men through this time of change and keep them strong as singers? Lots. The boys need to know that what is going on is normal and expected, and is just a part of developing.7 Strive to maintain an environment that is a safe place to sing and experiment with the voice. The sooner that each of the boys realizes that the snap, crackle, and pop of the voice change is something that either has happened, is happening, or will happen to everyone in the room, the more they will be willing to risk and try all of those things (vocalizes, non-musical sounds, etc.), which the director has planned to help them sing through the change. Confidence in Vocal Registration and Range Registration is an issue that is dealt with at all levels of singing. The confidence that we can produce a certain pitch is important, but our confidence in the quality of the sound we produce, as a result of the mixture of head voice, chest voice, resonating space, etc., is crucial. Nearly every work on this subject emphasizes a topdown approach, meaning that the lighter, brighter qualities of the head voice should be brought downward into the developing chest voice. This is not range specific, as the goal is to simply identify and strengthen the lighter, more blendable tone, and to bring these qualities into the lower range in order to relieve as much stress as possible on the vocal process and to optimize breath management. Gaining confidence in this area is achieved by exploring with the boys a series of warm-ups and vocalises that maintain the brilliance of the upper range, while sensitively exploring the newer bottom part of the range. With enough practice, singers will be able to navigate across these registers with little to no discernable strain or stress. Terry Barham8 identifies categories of warm-ups that are helpful in this respect. These include several unpitched vocalises such as yawns, sighs, and siren noises and small, compact descending passages, which help to sensitively bring the top part of the voice down through the passaggio. Exercises such as these, especially those that arent attached to repertoire, are helpful, because the boys will begin to gain for themselves a sense of accomplishment and confidence as they navigate these ranges and shifts more smoothly. Another important aspect in this area is to make sure that the idea of head tone or head voice is not first addressed only when the voice change starts to become an issue. Where possible, make younger treble voices who are unaffected by the onset of the voice change aware of registers (though relatively limited) within their own voices. The earlier that a boy is thinking in terms of registration and consistently demonstrating healthy tone placement, the easier it will be for him when the change in his vocal range first becomes problematic. Confidence to Avoid Unnecessary Effort One of the biggest problems with boys in various stages of the voice change is the exertion of too much effort. The inconsistency of the vocal mechanism often moves boys to strive for a false sense of control through overextension and misuse of their neck and jaw muscles. This is easily seen in a middle school-age chorus, where chins are jutted into the air on high pitches, and brought down to shoulder level on more comfortable notes. Such efforts result in unnecessary and typically detrimental tension. This also causes the muscles surrounding the vocal mechanism to tire more quickly, worsening the already tricky problem of vocal control due to the voice change.

So many activities in life and in school require that boys work hard and do things to become better. Society tells them they should study harder or practice more intensely, quite often in a spirit of competition. While male singers should definitely work hard to perfect their craft, this principle does not necessarily apply in the area of vocal production. The voiceand particularly the changing voiceworks best when it is allowed to operate freely, apart from any constricting or limiting forces. A maximized air stream which supports a relaxed, uninhibited vocal process is crucial to success with this age group. Boys need to experience the feeling of freedom and relaxation as it applies to the voice, and be able to recall this feeling daily so as to limit tension, strain, fatigue, and the possibility of long-term damage. Ensure that boys are encouraged to sing freely and openly with as little strain or stress as possible. Using the unpitched exercises described above is key in this area. Boys need to remove the element of matching exact pitches in order to experiment freely with producing light, unforced sounds. Instead of encouraging that boys make things happen vocally, encourage an attitude of letting things happen. Confidence in Their Role and Contribution Despite his directors best efforts, the voice change will still likely provide the young male singer with moments of frustration and disappointment. Boys who take pride in their work and effort may feel as though their role in the choir or contribution to the ensemble has been compromised, and feelings of inadequacy may result. This prospect is a delicate state, because, despite their rough exterior, the adolescent boys desire to seek approval extends to his director and others in his section. Continually hesitant performance may turn the boy away from singing altogether. Additionally, boys who are frustrated with their role may exhibit uncooperative behavior or become discipline problems. There are strategies that the director can do to help the young male singer in this area. Modifying or writing new vocal parts, changing original keys, or moving between different voice parts are isolated ways that may help. However, do not let the singer know you are doing this because of him. Simply say that more help is needed on a part that happens to fall within his comfortable range. Additionally, praise as much as possible those things that the boys can contribute despite pitch uncertainty. These boys can provide special attention to diction, phrasing, or articulation. No matter how small or limited a boys ability to contribute to the group, he should be praised for his work and gain a feeling of confidence in his efforts despite a temporarily modified role. As we work to produce wonderful choirs, we must also value our role in producing young men who are comfortable with their own vocal ability, and confidently prepared for a lifetime of music-making. Puberty and adolescence are difficult enough for children, and the problems encountered during the male voice change can add significantly to this awkward time. Navigating them through the tricky waters of the voice change with an end result of confident, healthy singing should remain a critical part of conducting and teaching.

NOTES 1 McKenzie, Duncan. Training the Boys Changing Voice. Rutgers University Press, 1956. 2 See the series of Changing Voice articles written and edited by Collins in the Choral Journal 28, October 1987 as well as The Cambiata Concept: More than Just About Changing Voices, Choral Journal 23 (December 1982). Also, the chapters on working with adolescent and changing voices in Collins Teaching Choral Music (Prentice Hall, 1999) are invaluable. 3 Cooksey, John. Working with Adolescent Voices.Concordia, 1999. Also see Cookseys The Development of a Contemporary, Eclectic Theory for the Training and Cultivation of the Junior High School Male Changing Voice (four parts), Choral Journal 18, October 1977 January 1978. 4 Titze, Ingo. Critical Periods of Vocal Change: Puberty. NATS Journal, January/February 1993. 5 Barham, Terry J. Strategies for Teaching Junior High and Middle School Male Singers: Master Teachers Speak. Santa Barbara Music Publishing, 2001. 6 Titze, Figure 2. 7 Kincaid, John. Someone Moved My Furniture! Strategies for Dealing with Male Voice Change. REPRISE: Alabama ACDA Newsletter, Fall 2005. 8 Barham, 3548. OriginallypublishedinChoralJournal,May2008

You might also like

- 80 Songs Children SingDocument40 pages80 Songs Children SingGabriela BernedoNo ratings yet

- Teaching Singing and Voice To Children and Adolescents PDFDocument16 pagesTeaching Singing and Voice To Children and Adolescents PDFjonathan100% (1)

- Popeil. Belting PDFDocument5 pagesPopeil. Belting PDFGerardo Viana JúniorNo ratings yet

- Common Sense Training For Changing Male Voices.Document6 pagesCommon Sense Training For Changing Male Voices.Marcus DanielNo ratings yet

- Anatomy of The LarynxDocument3 pagesAnatomy of The LarynxRakesh JadhavNo ratings yet

- Singing Through The Transition HandoutDocument3 pagesSinging Through The Transition HandoutJorge PipopiuxNo ratings yet

- The Changing Adolescent VoiceDocument4 pagesThe Changing Adolescent VoiceGayatri Nair100% (2)

- Choral Warm-Ups For Changing Adolescent Voices: Scholarworks at Georgia State UniversityDocument11 pagesChoral Warm-Ups For Changing Adolescent Voices: Scholarworks at Georgia State UniversityIsabel BarcelosNo ratings yet

- Crabb - Pre AdVoiceDocument13 pagesCrabb - Pre AdVoiceConnie HiiNo ratings yet

- Teaching Adolescent Voices (James Gregory)Document15 pagesTeaching Adolescent Voices (James Gregory)DanHasALamb100% (2)

- ABCD Vocal Technique Handout PDFDocument9 pagesABCD Vocal Technique Handout PDFRanieque RamosNo ratings yet

- The Boy's Voice A Book of Practical Information on The Training of Boys' Voices For Church Choirs, &c.From EverandThe Boy's Voice A Book of Practical Information on The Training of Boys' Voices For Church Choirs, &c.No ratings yet

- The Child-Voice in Singing treated from a physiological and a practical standpoint and especially adapted to schools and boy choirsFrom EverandThe Child-Voice in Singing treated from a physiological and a practical standpoint and especially adapted to schools and boy choirsNo ratings yet

- Vocal Music Success: Ideas, Hints, and Help for Singers and DirectorsFrom EverandVocal Music Success: Ideas, Hints, and Help for Singers and DirectorsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- The Child-Voice in Singing: Treated from a physiological and a practical standpoint and especially adapted to schools and boy choirsFrom EverandThe Child-Voice in Singing: Treated from a physiological and a practical standpoint and especially adapted to schools and boy choirsNo ratings yet

- The Quintessential Guide to Singing: For Voice Teachers and Very Curious StudentsFrom EverandThe Quintessential Guide to Singing: For Voice Teachers and Very Curious StudentsNo ratings yet

- Vocal Warm-UpDocument3 pagesVocal Warm-UpMarcus WellsNo ratings yet

- Puberphonia 11Document19 pagesPuberphonia 11jaguar1979100% (2)

- RICHARD MILLER-The-Structure-of-Singing-171-260 - 7-7Document1 pageRICHARD MILLER-The-Structure-of-Singing-171-260 - 7-7Cristina Marian100% (1)

- NO SINGING Voice Lesson 1 PDFDocument5 pagesNO SINGING Voice Lesson 1 PDFCecelia ChoirNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Twang (AES)Document1 pageIntroduction To Twang (AES)StuartNo ratings yet

- RAO, Doreen. Singing in The Twenty-First Century ... Singing A Better WorldDocument9 pagesRAO, Doreen. Singing in The Twenty-First Century ... Singing A Better WorldDryelen Chicon AnholettiNo ratings yet

- Vocal TractDocument16 pagesVocal TractniroelNo ratings yet

- Dancing BarefootDocument1 pageDancing BarefootmichaelNo ratings yet

- VoiceDocument3 pagesVoicebielrieraNo ratings yet

- Vocal Warm-Up Practices and PerceptionsDocument10 pagesVocal Warm-Up Practices and PerceptionsLoreto SaavedraNo ratings yet

- Assessment SingingDocument1 pageAssessment SingingSharon Mae Bitancur BarramedaNo ratings yet

- S R, R & E: Inging Iffs UNS MbellishmentsDocument3 pagesS R, R & E: Inging Iffs UNS MbellishmentsjsbachNo ratings yet

- The Deviant Noise Plan For A Better Singing Voice in 6 WeeksDocument6 pagesThe Deviant Noise Plan For A Better Singing Voice in 6 WeeksamritNo ratings yet

- Voice Lesson #4: Sound Production or PhonationDocument3 pagesVoice Lesson #4: Sound Production or PhonationBoedy IrhadtantoNo ratings yet

- Beginners Songbook SopranoDocument14 pagesBeginners Songbook SopranoJadir100% (1)

- Audition Info Rep. Choir v2023Document6 pagesAudition Info Rep. Choir v2023vallediosNo ratings yet

- Inside The Voice (Chapter 1 - Vocal Health and Awareness)Document8 pagesInside The Voice (Chapter 1 - Vocal Health and Awareness)Marcus Chapman100% (1)

- Vocal MusicDocument6 pagesVocal MusicbanikabebeNo ratings yet

- Singing Exercises 2009 PDFDocument8 pagesSinging Exercises 2009 PDFAvelyn Chua100% (1)

- Vocal Exercise For Singing Practice - 10 Exercises Explained PDFDocument4 pagesVocal Exercise For Singing Practice - 10 Exercises Explained PDFstarchaser_player100% (1)

- Interpretation in SingingDocument3 pagesInterpretation in SingingniniNo ratings yet

- Defining Open Throat' Through Content Analysis of Experts' Pedagogical PracticesDocument15 pagesDefining Open Throat' Through Content Analysis of Experts' Pedagogical PracticesBrenda IglesiasNo ratings yet

- 1.1 Vocal Exercise Notes PDFDocument5 pages1.1 Vocal Exercise Notes PDFJose Simon Bolivar MoranNo ratings yet

- Vocal ExercisesDocument3 pagesVocal ExercisescindyNo ratings yet

- Vocal Skill AssessmentDocument1 pageVocal Skill AssessmentKyle WearyNo ratings yet

- Fdocuments - in - Julia Davids and Stephen Latour Vocal Technique Vocal Technique Waveland PressDocument1 pageFdocuments - in - Julia Davids and Stephen Latour Vocal Technique Vocal Technique Waveland PressMohammad Haj mohammadiNo ratings yet

- A Singer's Notes: Preventing Vocal Nodules: Teresa Radomski, MMDocument21 pagesA Singer's Notes: Preventing Vocal Nodules: Teresa Radomski, MMDanis WaraNo ratings yet

- Vocal Pedagogy and Methods For DevelopinDocument9 pagesVocal Pedagogy and Methods For DevelopinPedro NascimentoNo ratings yet

- Marking Criteria SingingDocument1 pageMarking Criteria SingingLouisa Waldron100% (1)

- Adjustment of Glottal Configurations in Singing: Christian T. Herbst and Jan G. ŠvecDocument8 pagesAdjustment of Glottal Configurations in Singing: Christian T. Herbst and Jan G. ŠvecLindaNo ratings yet

- Lower Mandible Maneuver and Elite SingersDocument20 pagesLower Mandible Maneuver and Elite SingersBryan ChenNo ratings yet

- Singing Pleasure ExercisesDocument10 pagesSinging Pleasure ExercisesJenna RoubosNo ratings yet

- Singwise - Singwise - Breath Management ('Support' of The Singing Voice) - Merged PDFDocument125 pagesSingwise - Singwise - Breath Management ('Support' of The Singing Voice) - Merged PDFFrancisco HernandezNo ratings yet

- Vocal Warm UpDocument2 pagesVocal Warm Upapi-541653384No ratings yet

- Zygo PDFDocument10 pagesZygo PDFAlec BeattieNo ratings yet

- Build Your Own WarmupDocument8 pagesBuild Your Own WarmupBaia AramaraNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan 3 Student TeachingDocument3 pagesLesson Plan 3 Student Teachingapi-393150167No ratings yet

- Voice Lesson JournalDocument19 pagesVoice Lesson JournalJohnny Mac LaurieNo ratings yet

- Titzes Favorite Five VocalDocument1 pageTitzes Favorite Five VocalElton Nogueira FrancoNo ratings yet

- Jaw and Accoustic LawsDocument6 pagesJaw and Accoustic LawsPaulaRiveroNo ratings yet

- Breath ManagementDocument14 pagesBreath ManagementPaulaRiveroNo ratings yet

- Ten Singing Lessons PDFDocument243 pagesTen Singing Lessons PDFRavi Kanth0% (1)

- AudiopptDocument30 pagesAudiopptjai prakash naiduNo ratings yet

- Guitarist Presents - The Guitarist's Guide To Effects Pedals - 9th Edition - September 2023Document134 pagesGuitarist Presents - The Guitarist's Guide To Effects Pedals - 9th Edition - September 2023Jesus FernandezNo ratings yet

- SOS Magazine - Mixing On HeadphonesDocument4 pagesSOS Magazine - Mixing On HeadphonesVictor VeraNo ratings yet

- Physiology of The Voice PDFDocument18 pagesPhysiology of The Voice PDFJenna Marie Tolosa100% (1)

- Kartveluri Memkvidreoba XIII MIkautadze MaiaDocument11 pagesKartveluri Memkvidreoba XIII MIkautadze Maiakartvelianheritage XIIINo ratings yet

- 588SD Guide en-USDocument2 pages588SD Guide en-USdmaruNo ratings yet

- Enya BraveheartDocument17 pagesEnya BraveheartKimia FisikaNo ratings yet

- JBL-Studio S36 SpecsDocument2 pagesJBL-Studio S36 SpecsJhasmani VillegasNo ratings yet

- Digidesign 003Document4 pagesDigidesign 003zaydNo ratings yet

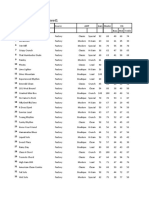

- Tracker Tsel Ver3Document1,754 pagesTracker Tsel Ver3telkominfra.jabotabekNo ratings yet

- 1985 Bob CarverDocument4 pages1985 Bob CarverAnonymous tJZ6HQNo ratings yet

- Manual Kenwood MC-60ADocument2 pagesManual Kenwood MC-60AArnaldoNo ratings yet

- DS Logitech Rally Accessories ENDocument4 pagesDS Logitech Rally Accessories ENanimecozNo ratings yet

- EXM005 JD800 SoundList Multi01 WDocument2 pagesEXM005 JD800 SoundList Multi01 Wjose antonioNo ratings yet

- RODECaster Pro II - DataSheet - V01 - 4Document1 pageRODECaster Pro II - DataSheet - V01 - 4lazlosNo ratings yet

- Audio Amplifier SystemDocument17 pagesAudio Amplifier SystemMisbah Saif100% (1)

- Tidal Wave: Brian Mudget Alan KeownDocument10 pagesTidal Wave: Brian Mudget Alan KeownAdib CarolineNo ratings yet

- THR10ii Patches SheetDocument18 pagesTHR10ii Patches Sheetrichard Van boxelNo ratings yet

- DigiTech Element Element XP Manual-25Document1 pageDigiTech Element Element XP Manual-25CaPitalNo ratings yet

- Tabla Conversion DB V DBFSDocument1 pageTabla Conversion DB V DBFSHector CardosoNo ratings yet

- Kurzweil SP76Document90 pagesKurzweil SP76Alfonso RojasNo ratings yet

- EBU Tech 3276-EDocument13 pagesEBU Tech 3276-EAptaeex ExtremaduraNo ratings yet

- A Banda (V. 6)Document21 pagesA Banda (V. 6)Christian Souza LeãoNo ratings yet

- Manual DSP DASDocument4 pagesManual DSP DASEmilio RamiresNo ratings yet

- StopMixingVocalsWrong PDFDocument31 pagesStopMixingVocalsWrong PDFJaime SaldanhaNo ratings yet

- MusicTechMag JULY 2017Document116 pagesMusicTechMag JULY 2017isshmangNo ratings yet

- 2 610 ManualDocument15 pages2 610 ManualANDRES GOMEZNo ratings yet

- Jogproof: Philips Portable CD PlayerDocument2 pagesJogproof: Philips Portable CD PlayerMarkNo ratings yet

- Warwick Protube Ix Manual Do UtilizadorDocument11 pagesWarwick Protube Ix Manual Do UtilizadorMateus MendesNo ratings yet