Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Law 1

Uploaded by

Jay RuizOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Law 1

Uploaded by

Jay RuizCopyright:

Available Formats

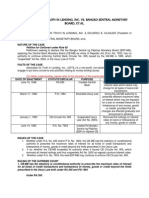

Social Security System Employees Association v.

CA Facts: On 9 June 1987, the officers and members of Social Security System Employees Ass ociation (SSSEA) staged a strike and barricaded the entrances to the SSS Buildin g, preventing non-striking employees from reporting for work and SSS members fro m transacting business with the SSS. The SSSEA went on strike after the SSS fail ed to act on the union's demands, which included: implementation of the provisio ns of the old SSS-SSSEA collective bargaining agreement (CBA) on check-off of un ion dues; payment of accrued overtime pay, night differential pay and holiday pa y; conversion of temporary or contractual employees with 6 months or more of ser vice into regular and permanent employees and their entitlement to the same sala ries, allowances and benefits given to other regular employees of the SSS; and p ayment of the children's allowance of P30.00, and after the SSS deducted certain amounts from the salaries of the employees and allegedly committed acts of disc rimination and unfair labor practices. The strike was reported by the Social Sec urity System (SSS) to the Public Sector Labor-Management Council, which ordered the strikers to return to work. The strikers refused to return to work. On 11 Ju ne 1987, the SSS filed with the Regional Trial Court of Quezon City a complaint for damages with a prayer for a writ of preliminary injunction against the SSSEA , Dionisio T. Baylon, Ramon Modesto, Juanito Madura, Reuben Zamora, Virgilio De Alday, Sergio Araneta, Placido Agustin, and Virgilio Magpayo, praying that a wri t of preliminary injunction be issued to enjoin the strike and that the strikers be ordered to return to work; that SSSEA, et. al. be ordered to pay damages; an d that the strike be declared illegal. On 11 June 1987, the RTC issued a tempora ry restraining order pending resolution of the application for a writ of prelimi nary injunction. In the meantime, the SSSEA, et. al. filed a motion to dismiss a lleging the trial court's lack of jurisdiction over the subject matter. On 22 Ju ly 1987, the court a quo denied the motion to dismiss and converted the restrain ing order into an injunction upon posting of a bond, after finding that the stri ke was illegal. As the SSSEA's motion for the reconsideration of the order was a lso denied on 14 August 1988, SSSEA ,et. al. filed a petition for certiorari and prohibition with preliminary injunction before the Supreme Court (GR 79577). In a resolution dated 21 October 1987, the Court, through the Third Division, reso lved to refer the case to the Court of Appeals. SSSEA, et. al. filed a motion fo r reconsideration thereof, but during its pendency the Court of Appeals on 9 Mar ch 1988 promulgated its decision on the referred case. SSSEA, et. al. moved to r ecall the Court of Appeals' decision. In the meantime, the Court on 29 June 1988 denied the motion for reconsideration in GR 97577 for being moot and academic. SSSEA, et. al.'s motion to recall the decision of the Court of Appeals was also denied in view of the Supreme Court's denial of the motion for reconsideration. SSSEA filed the petition to review the decision of the Court of Appeals. Issue: Whether SSS employees, in furtherance of labor interests, may conduct a strike. Held: The 1987 Constitution, in the Article on Social Justice and Human Rights (Art. X III, Sec. 3), provides that the State "shall guarantee the rights of all workers to self-organization, collective bargaining and negotiations, and peaceful conc erted activities, including the right to strike in accordance with law." By itse lf, this provision would seem to recognize the right of all workers and employee s, including those in the public sector, to strike. But the Constitution itself fails to expressly confirm this impression, for in the Sub-Article on the Civil Service Commission, it provides, after defining the scope of the civil service a s "all branches, subdivisions, instrumentalities, and agencies of the Government , including government-owned or controlled corporations with original charters," that "the right to self-organization shall not be denied to government employee s." Parenthetically, the Bill of Rights also provides that "the right of the peo ple, including those employed in the public and private sectors, to form unions,

associations, or societies for purposes not contrary to law shall not abridged" [Art. III, Sec. 8]. Thus, while there is no question that the Constitution reco gnizes the right of government employees to organize, it is silent as to whether such recognition also includes the right to strike. Resort to the intent of the framers of the organic law becomes helpful in understanding the meaning of thes e provisions. A reading of the proceedings of the Constitutional Commission that drafted the 1987 Constitution would show that in recognizing the right of gover nment employees to organize, the commissioners intended to limit the right to th e formation of unions or associations only, without including the right to strik e. Statutorily, it will be recalled that the Industrial Peace Act (CA 875), whic h was repealed by the Labor Code (PD 442) in 1974, expressly banned strikes by e mployees in the Government, including instrumentalities exercising governmental functions, but excluding entities entrusted with proprietary functions. Understa ndably, the Labor Code is silent as to whether or not government employees may s trike, for such are excluded from its coverage. But then the Civil Service Decre e (PD 807), is equally silent on the matter. Thus, on 1 June 1987, to implement the constitutional guarantee of the right of government employees to organize, t he President issued EO 180 which provides guidelines for the exercise of the rig ht to organize of government employees. In Section 14 thereof, it is provided th at "the Civil Service law and rules governing concerted activities and strikes i n the government service shall be observed, subject to any legislation that may be enacted by Congress." The President was apparently referring to Memorandum Ci rcular No. 6, series of 1987 of the Civil Service Commission under date 12 April 1987 which, "prior to the enactment by Congress of applicable laws concerning s trike by government employees enjoins under pain of administrative sanctions, al l government officers and employees from staging strikes, demonstrations, mass l eaves, walk-outs and other forms of mass action which will result in temporary s toppage or disruption of public service." The air was thus cleared of the confus ion. At present, in the absence of any legislation allowing government employees to strike, recognizing their right to do so, or regulating the exercise of the right, they are prohibited from striking, by express provision of Memorandum Cir cular 6 and as implied in EO 180. The Court is of the considered view that the S SS employees are covered by the prohibition against strikes. Considering that un der the 1987 Constitution "the civil service embraces all branches, subdivisions , instrumentalities, and agencies of the Government, including government-owned or controlled corporations with original charters" and that the SSS is one such government-controlled corporation with an original charter, having been created under RA 1161, its employees are part of the civil service and are covered by th e Civil Service Commission's memorandum prohibiting strikes. This being the case , the strike staged by the employees of the SSS was illegal. In fine, government employees may through their unions or associations, either petition the Congres s for the betterment of the terms and conditions of employment which are within the ambit of legislation or negotiate with the appropriate government agencies f or the improvement of those which are not fixed by law. If there be any unresolv ed grievances, the dispute may be referred to the Public Sector Labor-Management Council for appropriate action. But employees in the civil service may not reso rt to strikes, walkouts and other temporary work stoppages, like workers in the private sector, to pressure the Government to accede to their demands. As now pr ovided under Sec. 4, Rule III of the Rules and Regulations to Govern the Exercis e of the Right of Government Employees to Self-Organization, which took effect a fter the present dispute arose, "the terms and conditions of employment in the g overnment, including any political subdivision or instrumentality thereof and go vernment-owned and controlled corporations with original charters are governed b y law and employees therein shall not strike for the purpose of securing changes thereof."

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- E 342Document2 pagesE 342Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- 111111Document1 page111111Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- 111111Document1 page111111Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- 111111Document1 page111111Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- 111111Document1 page111111Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- E 342Document2 pagesE 342Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- E 342Document2 pagesE 342Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- Title ElevenDocument2 pagesTitle ElevenJay RuizNo ratings yet

- 1111Document1 page1111Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- 123Document1 page123Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- LegetDocument1 pageLegetJay RuizNo ratings yet

- 2222Document2 pages2222Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- 1Document1 page1Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- 123Document1 page123Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- Legal MedicineDocument12 pagesLegal MedicineJay RuizNo ratings yet

- 123Document2 pages123Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- 123Document1 page123Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- 123Document1 page123Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- Advocates of Til vs. BSPDocument3 pagesAdvocates of Til vs. BSPIrene RamiloNo ratings yet

- 123Document1 page123Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- 123Document1 page123Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- 12213123Document12 pages12213123Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- Suggested Answers in Criminal Law Bar ExamsDocument88 pagesSuggested Answers in Criminal Law Bar ExamsRoni Tapeño75% (8)

- Lambino v. ComelecDocument3 pagesLambino v. ComelecRm GalvezNo ratings yet

- Hon. Patricia A. Sto - Tomas, Rosalinda Baldoz and Lucita Lazo, PetitionersDocument9 pagesHon. Patricia A. Sto - Tomas, Rosalinda Baldoz and Lucita Lazo, PetitionersJay RuizNo ratings yet

- Law 1Document3 pagesLaw 1Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- Ernesto Hebron, ComplainantDocument6 pagesErnesto Hebron, ComplainantJay RuizNo ratings yet

- Atong Paglaum, Inc. vs. Commission On ElectionsDocument143 pagesAtong Paglaum, Inc. vs. Commission On ElectionsJay RuizNo ratings yet

- Law 1Document2 pagesLaw 1Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- Law 1Document1 pageLaw 1Jay RuizNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh Circuit.: No. 88-7365 Non-Argument CalendarDocument5 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Eleventh Circuit.: No. 88-7365 Non-Argument CalendarScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 5-15 Resolution For Stock Issuance To Certain PersonsDocument2 pages5-15 Resolution For Stock Issuance To Certain PersonsDaniel100% (3)

- Robin L BrownDocument46 pagesRobin L BrownMud PyeNo ratings yet

- Income Tax AuthoritiesDocument28 pagesIncome Tax Authoritiesabhi9998No ratings yet

- Omnibus Sworn Statement: AffidavitDocument2 pagesOmnibus Sworn Statement: AffidavitMark Dave Joven Lamasan AlentonNo ratings yet

- Bank Bumiputra (M) BHD V Hashbudin Bin HashiDocument10 pagesBank Bumiputra (M) BHD V Hashbudin Bin HashiNorlia Md DesaNo ratings yet

- 3 - ForM F Gratuity (Sample)Document4 pages3 - ForM F Gratuity (Sample)Rajdeep GaharwarNo ratings yet

- Torts & Damages Actual Damages Case DigestsDocument4 pagesTorts & Damages Actual Damages Case DigestsNilsy YnzonNo ratings yet

- Fiduciary DutiesDocument34 pagesFiduciary DutiessdfklmjsdlklskfjdNo ratings yet

- DEED OF DONATION Brgy. San Juan BautistaDocument4 pagesDEED OF DONATION Brgy. San Juan BautistaAedrian MacawiliNo ratings yet

- Land S1 - Statutory AuthorityDocument3 pagesLand S1 - Statutory AuthorityNadia AbdulNo ratings yet

- Office of The General Manager District Industries Centre, Cuttack, Odisha Entrepreneur Identification NumberDocument1 pageOffice of The General Manager District Industries Centre, Cuttack, Odisha Entrepreneur Identification Numberdeepak kumarNo ratings yet

- Philippine Commercial International Bank v. GomezDocument5 pagesPhilippine Commercial International Bank v. GomezVic FrondaNo ratings yet

- Sample Points and Authorities in Support of OSC To Modify Child Support in CaliforniaDocument3 pagesSample Points and Authorities in Support of OSC To Modify Child Support in CaliforniaStan Burman0% (1)

- Insurance Cases Blucross Vs NEOMIDocument4 pagesInsurance Cases Blucross Vs NEOMIvivivioletteNo ratings yet

- Magat Vs MedialdeaDocument3 pagesMagat Vs MedialdeaGale Charm SeñerezNo ratings yet

- Deed of DonationDocument3 pagesDeed of DonationJerome BanaybanayNo ratings yet

- 174626Document13 pages174626The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeNo ratings yet

- Rogelio Rosario Vs Rizalito AlbaDocument1 pageRogelio Rosario Vs Rizalito AlbaBourgeoisified LloydNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 Negotiable InstrumentsDocument23 pagesChapter 6 Negotiable InstrumentsDoreen Gail Samorano PuliranNo ratings yet

- Lampano Vs JoseDocument1 pageLampano Vs JoseJayson CamasuraNo ratings yet

- Distinction Between Partnership Firm and Hindu Joint FamilyDocument1 pageDistinction Between Partnership Firm and Hindu Joint FamilyRåjå MãxNo ratings yet

- Jomark Orpilla Holographic WillDocument3 pagesJomark Orpilla Holographic Willmark OrpillaNo ratings yet

- Castillo v. PascoDocument2 pagesCastillo v. PascoDondon SalesNo ratings yet

- Special Power Attorney TemplateDocument2 pagesSpecial Power Attorney TemplateNoel Ephraim AntiguaNo ratings yet

- Julhash Mollah v. BangladeshDocument5 pagesJulhash Mollah v. BangladeshActusReusJurorNo ratings yet

- Affidavit For Order Establishing Custody, Visitation and Child Support Without Appearance of PartiesDocument4 pagesAffidavit For Order Establishing Custody, Visitation and Child Support Without Appearance of PartiesballNo ratings yet

- Anti-Bullying Act (RA 10627)Document2 pagesAnti-Bullying Act (RA 10627)venickeeNo ratings yet

- United States vs. Laurente Rey G.R. No. L-3326 September 7, 1907 Loss of Possession, RobberyDocument3 pagesUnited States vs. Laurente Rey G.R. No. L-3326 September 7, 1907 Loss of Possession, RobberyDenver GamlosenNo ratings yet

- Toribio CaseDocument5 pagesToribio CaseGarri AtaydeNo ratings yet