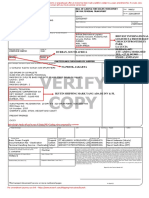

Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Partnership Cases

Uploaded by

Jayran Bay-anOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Partnership Cases

Uploaded by

Jayran Bay-anCopyright:

Available Formats

Commissioner of Internal Revenue vs.William j. Suter and the Court of Tax AppealsG.R. No.

L-25532, February 28, 1969Fact s: A limited partnership, named "William J. Suter 'Morcoin' Co., Ltd.," was formed on 30 Sep-tember 1947 by William J. Suter as the general partner, and Julia Spirig and Gustav Carlson, as thelimited partners. The partners contributed, respectively, P20,000.00, P18,000.00 and P2,000.00 tothe partne rship. On 1 Octo be r 1947, the limi te d partne rship was re giste re d with the Se curitie s and Exchange Commission.In 1948, general partner Suter and limited partner Spirig got married and, thereafter, on 18December 1948, limited partner Carlson sold his share in the partnership to Suter and his wife. Thesale was duly recorded with the Securities and Exchange Commission on 20 December 1948.The limited partnership had been filing its income tax returns as a corporation, without ob- jection by the Commissioner of Internal Revenue, until in 1959 when the latter, in an assessment,consolidate d the income of the firm and the individual i ncomes of the partne rs -spouse s Sute r and S p i r i g r e s u l t i n g i n a d e t e r m i n a t i o n o f a d e f i c i e n c y i n c o m e t a x a g a i n s t r e s p o n d e n t S u t e r i n t h e amount of P2,678.06 for 1954 and P4,567.00 for 1955. Partner-Spouses Suter protested the assess-ment. Issue: Whe the r or no t the partne rship was dissolve d afte r the marriage of the partne rs, William J. Suter and Julia Spirig Suter and the subsequent sale to them by the remaining partner, Gustav Carl-son? Ruling: William J. Sute r "Morcoin " Co., L td. was not a univ e rsal partne rship, but a particula r one since the contributions of the partners were fixed sums of money, P20,000.00 by William Suter andP18,000.00 by Julia Spirig and neither one of them was an industrial partner. It follows that the firmwas not a partne rship tha t spouse s we re forbidde n to e nte r by Artic le 1677 of the Civil Code of 1889 (now Article 1782 of the New Civil Code). Nor could the subsequent marriage of the partners operate to dissolve it, such marriage not being one of the causes provided for that purpose by law. The capital contributions of partnersWilliam J. Suter and Julia Spirig were separately owned and contributed by them before their mar-riage; and after they were joined in wedlock, such contributions remained their respective separate property under the Spanish Civil Code (Article 1396)

PETITION FOR AUTHORITY TO CONTINUE USE OF THE FIRM NAME SYCIP, SALAZAR, FELICIANO, HERNANDEZ & CASTILLO. by Maki PETITION FOR AUTHORITY TO CONTINUE USE OF THE FIRM NAME SYCIP, SALAZAR, FELICIANO, HERNANDEZ & CASTILLO. July 30, 1979 Facts: Petitions were filed by the surviving partners of Atty. Alexander Sycip, who died on May 5, 1975 and by the surviving partners of Atty. Herminio Ozaeta, who died on February 14, 1976, praying that they be allowed to continue using, in the names of their firms, the names of partners who had passed away. Petitioners contend that the continued use of the name of a deceased or former partner when permissible by local custom, is not unethical but care should be taken that no imposition or deception is practiced through this use. They also contend that no local custom prohibits the continued use of a deceased partners name in a professional firms name; there is no custom or usage in the Ph ilippines, or at least in the Greater Manila Area, which recognizes that the name of a law firm necessarily identifies the individual members of the firm. Issue: WON the surviving partners may be allowed by the court to retain the name of the partners who already passed away in the name of the firm? NO Held: In the case of Register of Deeds of Manila vs. China Banking Corporation, the SC said: The Court believes that, in view of the personal and confidential nature of the relations between attorney and client, and the high standards demanded in the canons of professional ethics, no practice should be allowed which even in a remote degree could give rise to the possibility of deception. Said attorneys are accordingly advised to drop the names of the deceased partners from their firm name. The public relations value of the use of an old firm name can tend to create undue advantages and disadvantages in the practice of the profession. An able lawyer without connections will have to make a name for himself starting from scratch. Another able lawyer, who can join an old firm, can initially ride on that old firms reputation established by deceased partners. The court also made the difference from the law firms and business corporations: A partnership for the practice of law is not a legal entity. It is a mere relationship or association for a particular purpose. It is not a partnership formed for the purpose of carrying on trade or business or of holding property. 11 Thus, it has been stated that the use of a nom de plume, assumed or trade name in law practice is improper.

We find such proof of the existence of a local custom, and of the elements requisite to constitute the same, wanting herein. Merely because something is done as a matter of practice does not mean that Courts can rely on the same for purposes of adjudication as a juridical custom. Petition suffers legal and ethical impediment. OMMISSIONER OF CUSTOMS V CAMPOS RUEDA & CTA 11FEB L 55020 | August 20, 1990 | J. Medialdea

Facts: Campos Rueda imported 46 cartons or 27,000 pieces of Tungsol flashers. Before the goods arrived at the port of Manila, Campos Rueda filed with the Collector of Customs of Manila a request for value information for the declaration of the imported flashers under Tariff Heading No. 85.09 of the Tariff and Customs Code at 30% ad valorem duty, for classification purpose. The Customs appraiser however, re-classified the goods under Tariff Heading No. 85.19 of the Tariff and Customs Code at 50% ad valorem. When the goods arrived at the port of Manila, Campos Rueda immediately filed a Customs Import Entry and Internal Revenue Declaration under Tariff Heading No. 85.19 of the Tariff and Customs Code at 50% ad valorem but, under protest and paid duties and taxes on the goods, also under protest. It then filed a timely protest against the re-classification resulting in the payment of additional customs duty and advance sales tax and prayed for the refund of the said. The Collector of Customs dismissed the protest. Campos Rueda appealed to the Commissioner but was denied, and then appealed to CTA which modified the Commissioners decision by ordering the refund to Campos Rueda of the sum of the additional customs duty b ut not the advance sales tax. The Commissioner now appeals via petition for review the said decision.

Issue: W/N Campos Rueda should pay 30% or 50% ad valorem duty

Held: 30%. TH No 85.09 of the Tariff and Customs Code provides: 85.09. Electrical lighting and signalling equipment and electrical windscreen wipers, defrosters and demisters, for cycles or motor vehicles ad val. 30%. On the other hand, the same Code provides under TH No. 85.19: 85.19. Electrical apparatus for making and breaking electrical circuits, for the protection of electrical circuits, or for making connections to or in electric circuits (for example, switches, relays, fuses, lighting arresters, surge suppressors, plugs, lamp-holders and junction boxes); resistors, fixed or variable (including potentiometers), other than heating resistors, printed circuits, switch boards (other than telephone switchboards) and control panels: In finding for Campos Rueda, CTA found that it has adduced sufficient evidence to establish the general purpose or predominating use to which flashers are applied, and for which petitioner imported them, is precisely as electrical equipment for signalling purposes for motor vehicles; that is, to signal or indicate a right or left hand turn by means of electrical flashes in front and at the rear of motor vehicles and not merely as electrical apparatus as the Commissioner claims. It is the predominating use to which articles are generally applied or used that determines their character for the purpose of fixing the duty, and not the specific or special use which any particular importer may make of the articles imported.

Parts of machines, apparatus of appliances which are suitable for use solely or principally with a particular kind of machine or with a number of machines falling within a specific heading, as a rule, are to be classified with the machines in the same heading. Also, the law does not provide that an article imported for electrical lighting and signalling equipment for motor vehicles falling under Tariff Heading No. 85.09, if imported alone, shall be classified under Tariff Heading No. 85.19 as electrical apparatus for making and breaking electrical circuits that provision should not be read into the law per the circular of the former Acting Customs Collector. Petition denied. CTA decision affirmed.

TAI TONG CHUACHE AND CO. V.INSURANCE COMMISION158 SCRA 336 A partnership may sue and be sued in its name or byits duly authorized representative. 13 PASCUAL V. COMMISSION OF INTERNALREVENUE166 SCRA 560 The sharing of returns doesnt in itself establish apartnership. In order to constitute a partnership intersese, there must be: an intent to form the same;generally participating in both profits and losses; andsuch a community of interest, as far as third personsare concerned as enables each party to make contract,manage the business, and dispose of the wholeproperty. 14 FORTIS V. GUTIERREZ HERMANOS6 PHIL 100 The general manager of a general partnership hasauthority to employ a bookkeeper, and a contract thusmade was valid, though not in writing. 15 DELUAO V. CASTEEL26 SCRA 475 The declarations of one partner, not made in thepresence of his co-partner, are not competent to provethe existence of a partnership between them as againstsuch other partner. The existence of a partnershipcannot be established by general reputation, rumor, orhearsay. 16 LOZANO V. DEPAKAKIBO107 PHIL 728 An equipment which was contributed by one of thepartners to the partnership becomes the property of the partnership and as such cannot be disposed of bythe party contributing the same without the consent of the partnership or the other partner. 17 KIEL V. ESTATE OF P.S SABERT46 PHIL 19318 AGAD V. MABATO23 SCRA 1223 A partnership may be constituted in any form, exceptwhere immovable property or real rights arecontributed thereto, in which case, a public instrumentshall be necessary. A contract of partnership is void,whenever immovable property is contributed thereto, if inventory of said property is not made, signed by theparties, and attached to the public instrument.

CAMPOS RUEDA & CO. VS. PACIFICCOMMERCIAL CO. ET. AL.Facts: T h i s c a s e i n v o l v e s t h e a p p l i c a t i o n b y t h e p e t i t i o n e r f o r a j u d i c i a l d e c r e e a d j u d g i n g i t s e l f insolvent. The limited partnership of Campos Rueda& Co. was, and is , in debted to Pacific Comme rcial Co., the Asiatic Petroleum Co. and the International Banking Corporation in various sums amounting tonot less than Php1000.00, payable in the Philippines,which we re not paid more than thi rty day s prior tot h e d a t e o f t h e i r f i l i n g o f t h e a p p l i c a t i o n f o r involuntary insolvency. The lower court denied thepetition because it was not proven, nor alleged, thatthe members of the aforesaid firm were insolvent atthe time of the application was filed; and that as saidpartne rs are pe rsonally and solid arily liable for the conse que nce s of the transaction of partne rship, itcannot be adjudged insolvent so long as the partnersare not al le ged and prove n to be insolve nt. Fromthis judgment, the petitioners appeal to the SupremeCourt. Issue: Whether or not a limited partnership, such asthe petitioner, which has failed to pay its obligationswith thre e cre ditors for more than th irty days, may be held to have committed an act of insolvency, andthereby be adjudged insolvent against its will. Held: In the Philippines, a limited partnership dulyorganize d in a ccordance with la w has a pe rsonalitydistinct from that o f i ts me mbe rs. If i t commi ts an act of bankruptcy, such a s tha t o f faili ng for more t h a n 3 0 d a y s t o p a y d e b t s a m o u n t i n g t o PhP1000.000 or more, it may be adjudged insolventon the pe tition of thre e of its c re ditors al though i ts m e m b e r s m a y n o t b e i n s o l v e n t . U n d e r o u r Insolvency Law, one of the acts of bankruptcy uponwhich an adjudicatio n of involunta ry insolve ncy ispre dicate d is the failu re of a partne rship to pay its obligations with three creditors for a period of morethan 30 days.On the contrary , some courts of the Uni te d State shave he ld tha t a partne rship may not be adjudge dinsolve nt in a n i nvoluntary insolve ncy proceedingunless all of its members are insolvent, while othershave maintaine d a contrary vie w. Ne ve rthe le ss, itmust be borne in mind that under American commonl a w , p a r t n e r s h i p s h a v e n o j u r i d i c a l p e r s o n a l i t y independent from that of its members. Therefore, it having been proven that the partnershipCampos Rueda & Co. failed for more than 30 days topay its ob ligations to the he re in re sponde nts, the p a r t n e r s h i p h a v e t h e r i g h t t o a j u d i c i a l d e c r e e d e c l a r i n g t h e i n v o l u n t a r y i n s o l v e n c y o f s a i d partnership. JO CHUNG CANG vs. PACIFIC COMMERCIAL Co.Facts: In an insolvency proceedings of petitioner-establishment, Sociedad Mercantil, Teck Seing &Co., Ltd., creditors, Pacific Commercial and othersfiled a motion with the Court to declare the individualpartners parties to the proceeding, for each to file aninventory, and for each to be adjudicated asinsolvent debtors. Issue: What is the nature of the mercantileestablishment, Teck Seing & Co., Ltd.? Held : The contract of partnership established ageneral partnership.By process of elimination, Teck Seing & Co., Ltd. Isnot a corporation nor an accidental partnership (jointaccount association). To establish a limited partnership, there must be, atleast, one general partner

and the name of at leastone of the general partners must appear in the firmname. This requirement has not been fulfilled. Thosewho seek to avail themselves of the protection of laws permitting the creation of limited partnershipsmust the show a substantially full compliance withsuch laws. It must be noted that all the requirementsof the Code have been met w/ the sole exception of that relating to the composition of the firm name. The legal intention deducible from the acts of theparties controls in determining the existence of apartnership. If they intend to do a thing w/c in lawconstitutes a partnership, they are partners althoughtheir very purpose was to avoid the creation of suchrelation. Here the intention of the persons makingup, Teck Seing & Co., Ltd. Was to establishpartnership w/c they erroneously denominated as alimited partnership. Antonia Torres vs Court of Appeals on June 24, 2012 Business Organization Partnership, Agency, Trust Sharing of Loss in a Partnership Industrial Partner In 1969, sisters Antonia Torres and Emeteria Baring entered into a joint venture agreement with Manuel Torres. Under the agreement, the sisters agreed to execute a deed of sale in favor Manuel over a parcel of land, the sisters received no cash payment from Manuel but the promise of profits (60% for the sisters and 40% for Manuel) said parcel of land is to be developed as a subdivision.

Manuel then had the title of the land transferred in his name and he subsequently mortgaged the property. He used the proceeds from the mortgage to start building roads, curbs and gutters. Manuel also contracted an engineering firm for the building of housing units. But due to adverse claims in the land, prospective buyers were scared off and the subdivision project eventually failed.

The sisters then filed a civil case against Manuel for damages equivalent to 60% of the value of the property, which according to the sisters, is whats due them as per the contract.

The lower court ruled in favor of Manuel and the Court of Appeals affirmed the lower court.

The sisters then appealed before the Supreme Court where they argued that there is no partnership between them and Manuel because the joint venture agreement is void.

ISSUE: Whether or not there exists a partnership. HELD: Yes. The joint venture agreement the sisters entered into with Manuel is a partnership agreement whereby they agreed to contribute property (their land) which was to be developed as a subdivision. While on the other hand, though Manuel did not contribute capital, he is an industrial partner for his contribution for general expenses and other costs. Furthermore, the income from the said project would be divided according to the stipulated percentage (60-40). Clearly, the contract manifested the intention of the parties to form a partnership. Further still, the sisters cannot invoke their right to the 60% value of the property and at the same time deny the same contract which entitles them to it. At any rate, the failure of the partnership cannot be blamed on the sisters, nor can it be blamed to Manuel (the sisters on their appeal did not show evidence as to Manuels fault in the failure of the partnership). The sisters must then bear their loss (which is 60%). Manuel does not bear the loss of the other 40% because as an industrial partner he is exempt from losses.

December 4, 1906 G.R. No. 2880 FRANK S. BOURNS, plaintiff-appellee, vs. D. M. CARMAN, ET AL., defendants-appellants.

W. A. Kincaid for appellants. J. N. Wolfson for appellee. MAPA, J.: The plaintiff in this action seeks to recover the sum of $437.50, United States currency, balance due on a contract for the sawing of lumber for the lumber yard of Lo-Chim-Lim. The contract relating to the said work was entered into by the said Lo-Chim-Lim, acting as in his own name with the plaintiff, and it appears that the said Lo-Chim-Lim personally agreed to pay for the work himself. The plaintiff, however, has brought this action against Lo-Chim-Lim and his codefendants jointly, alleging that, at the time the contract was made, they were the joint proprietors and operators of the said lumber yard engaged in the purchase and sale of lumber under the name and style of Lo-Chim-Lim. Apparently the plaintiff tries to show by the words above italicized that the other defendants were the partners of Lo-Chim-Lim in the said lumber-yard business. The court below dismissed the action as to the defendants D. M. Carman and Fulgencio Tan-Tongco on the ground that they were not the partners of Lo-Chim-Lim, and rendered judgment against the other defendants for the amount claimed in the complaint with the costs of proceedings. Vicente Palanca and Go-Tauco only excepted to the said judgment, moved for a new trial, and have brought the case to this court by bill of exceptions. The evidence of record shows, according to the jud gment of the court, That Lo-Chim-Lim had a certain lumber yard in Calle Lemery of the city of Manila, and that he was the manager of the same, having ordered the plaintiff to do some work for him at his sawmill in the city of Manila; and that Vicente Palanca was his partner, and had an interest in the said business as well as in the profits and losses thereof . . ., and that Go-Tuaco received part of the earnings of the lumber yard in the management of which he was interested. The court below accordingly found that Lo-Chim-Lim, Vicente Palanca, Go-Tuaco had a lumber yard in Calle Lemmery of the city of Manila in the year 1904, and participated in the profits and losses of business and that Lo-Chim-Lim was managing partner of the said lumber yard. In other words, coparticipants with the said Lo-Chim-Lim in the business in question. Although the evidence upon this point as stated by the by the however, that is plainly and manifestly in conflict with the above finding of that court. Such finding should therefore be sustained. The question thus raised is, therefore, purely one of law and reduces itself to determining the real legal nature of the participation which the appellants had in Lo-Chim-Lims lumber yard, and consequently their liability toward the plaintiff, in connection with the transaction which gave rise to the present suit. It seems that the alleged partnership between Lo-Chim-Lim and the appellants was formed by verbal agreement only. At least there is no evidence tending to show that the said agreement was reduced to writing, or that it was ever recorded in a public instrument. Moreover, that partnership had no corporate name. The plaintiff himself alleges in his complaint that the partnership was engaged in business under the name and style of Lo-Chim-Lim only, which according to the evidence was the name of one of the defendants. On the other hand, and this is very important, it does not appear that there was any mutual agreement, between the parties, and if there were any, it has not been shown what the agreement was. As far as the evidence shows it seems that the business was conducted by Lo-ChimLim in his own name, although he gave to the appellants a share was has been shown with certainty. The contracts made with the plaintiff were made by Lo-Chim-Lim individually in his own name, and there is no evidence that the partnership over contracted in any other form. Under such circumstances we find nothing upon which to consider this partnership other than as a partnership of cuentas en participacion. It may be that, as a matter of fact, it is something different, but a simple business and scant evidence introduced by the partnership We see nothing, according to the evidence, but a simple business conducted by Lo-Chim-Lim exclusively, in his own name, the names of other persons interested in the profits and losses of the business nowhere appearing. A partnership constituted in such a manner, the existence of which was only known to those who had an interest in the same, being no mutual agreements between the partners and without a corporate name indicating to the public in some way that there were other people besides the one who ostensibly managed and conducted the business, is exactly the accidental partnership of cuentas en participacion defined in article 239 of the Code of Commerce.

Those who contract with the person under whose name the business of such partnership of cuentas en participacion is conducted, shall have only a right of action against such person and not against the other persons interested, and the latter, on the other hand, shall have no right of action against the third person who contracted with the manager unless such manager formally transfers his right to them. (Article 242 of the Code of Commerce.) It follows, therefore that the plaintiff has no right to demand from the appellants the payment of the amount claimed in the complaint, as Lo-Chim-Lim was the only one who contracted with him. the action of the plaintiff lacks, therefore, a legal foundation and should be accordingly dismissed. The judgment appealed from this hereby reversed and the appellants are absolved of the complaint without express provisions as to the costs of both instances. After the expiration of twenty days let judgment be entered in accordance herewith, and ten days thereafter the cause be remanded to the court below for execution. So ordered.

Pioneer Insurance & Surety Corporation vs Court of Appeals on November 18, 2012 175 SCRA 668 -Business Organization Corporation Law When De Facto Partnership Does Not Exist Jacob Lim was the owner of Southern Air Lines, a single proprietorship. In 1965, Lim convinced Constancio Maglana, Modesto Cervantes, Francisco Cervantes, and Border Machinery and Heavy Equipment Company (BORMAHECO) to contribute funds and to buy two aircrafts which would form part a corporation which will be the expansion of Southern Air Lines. Maglana et al then contributed and delivered money to Lim.

But instead of using the money given to him to pay in full the aircrafts, Lim, without the knowledge of Maglana et al, made an agreement with Pioneer Insurance for the latter to insure the two aircrafts which were brought in installment from Japan Domestic Airlines (JDA) using said aircrafts as security. So when Lim defaulted from paying JDA, the two aircrafts were foreclosed by Pioneer Insurance.

It was established that no corporation was formally formed between Lim and Maglana et al.

ISSUE: Whether or not Maglana et al must share in the loss as general partners. HELD: No. There was no de facto partnership. Ordinarily, when co-investors agreed to do business through a corporation but failed to incorporate, a de facto partnership would have been formed, and as such, all must share in the losses and/or gains of the venture in proportion to their contribution. But in this case, it was shown that Lim did not have the intent to form a corporation with Maglana et al. This can be inferred from acts of unilaterally taking out a surety from Pioneer Insurance and not using the funds he got from Maglana et al. The record shows that Lim was acting on his own and not in behalf of his other would-be incorporators in transacting the sale of the airplanes and spare parts. Evangelista, et al. v. CIR, GR No. L-9996, October 15, 1957 Facts: Herein petitioners seek a review of CTAs decision holding them liable for income tax, real estate dealers tax and residence tax. As stipulated, petitioners borrowed from their father a certain sum for the purpose of buying real properties. Within February 1943 to April 1994, they have bought parcels of land from different persons, the management of said properties was charged to their brother Simeon evidenced by a document. These properties were then leased or rented to various tenants. On September 1954, CIR demanded the payment of income tax on corporations, real estate dealers fixed tax, and corporation residence tax to which the petitioners seek to be absolved from such payment. Issue: Whether petitioners are subject to the tax on corporations. Ruling: The Court ruled that with respect to the tax on corporations, the issue hinges on the meaning of the terms corporation and partnership as used in Section 24 (provides that a tax shall be levied on every corporation no matter how created o r organized except general co-partnerships) and 84 (provides that the term corporation includes among others, partnership) of the NIRC. Pursuant to Article 1767, NCC (provides for the concept of partnership), its essential elements are: (a) an agreement to contribute money, property or industry to a common fund; and (b) intent to divide the profits among the contracting parties.

It is of the opinion of the Court that the first element is undoubtedly present for petitioners have agreed to, and did, contribute money and property to a common fund. As to the second element, the Court fully satisfied that their purpose was to engage in real estate transactions for monetary gain and then divide the same among themselves as indicated by the following circumstances: 1. The common fund was not something they found already in existence nor a property inherited by them pro indiviso. It was created purposely, jointly borrowing a substantial portion thereof in order to establish said common fund; 2. They invested the same not merely in one transaction, but in a series of transactions. The number of lots acquired and transactions undertake is strongly indicative of a pattern or common design that was not limited to the conservation and preservation of the aforementioned common fund or even of the property acquired. In other words, one cannot but perceive a character of habitually peculiar to business transactions engaged in the purpose of gain; 3. Said properties were not devoted to residential purposes, or to other personal uses, of petitioners but were leased separately to several persons; 4. They were under the management of one person where the affairs relative to said properties have been handled as if the same belonged to a corporation or business and enterprise operated for profit; 5. Existed for more than ten years, or, to be exact, over fifteen years, since the first property was acquired, and over twelve years, since Simeon Evangelista became the manager; 6. Petitioners have not testified or introduced any evidence, either on their purpose in creating the set up already adverted to, or on the causes for its continued existence. The collective effect of these circumstances is such as to leave no room for doubt on the existence of said intent in petitioners herein. Also, petitioners argument that their being mere co -owners did not create a separate legal entity was rejected because, according to the Court, the tax in question is one imposed upon "corporations", which, strictly speaking, are distinct and different from "partnerships". When the NIRC includes "partnerships" among the entities subject to the tax on "corporations", said Code must allude, therefore, to organizations which are not necessarily "partnerships", in the technical sense of the term. The qualifying expression found in Section 24 and 84(b) clearly indicates that a joint venture need not be undertaken in any of the standard forms, or in conformity with the usual requirements of the law on partnerships, in order that one could be deemed constituted for purposes of the tax on corporations. Accordingly, the lawmaker could not have regarded that personality as a condition essential to the existence of the partnerships therein referred to. For purposes of the tax on corporations, NIRC includes these partnerships - with the exception only of duly registered general co partnerships - within the purview of the term "corporation." It is, therefore, clear that petitioners herein constitute a partnership, insofar as said Code is concerned and are subject to the income tax for corporations. As regards the residence of tax for corporations (Section 2 of CA No. 465), it is analogous to that of section 24 and 84 (b) of the NIRC. It is apparent that the terms "corporation" and "partnership" are used in both statutes with substantially the same meaning. Consequently, petitioners are subject, also, to the residence tax for corporations. Finally, on the issues of being liable for real estate dealers tax, they are also liab le for the same because the records show that they have habitually engaged in leasing said properties whose yearly gross rentals exceeds P3,000.00 a year. Evangelista vs. Santos [GR L-1721, 19 May 1950] Facts: Juan D. Evangelista, et. al. are minority stockholders of the Vitali Lumber Company, Inc., a Philippine corporation organized for the exploitation of a lumber concession in Zamboanga, Philippines, while Rafael Santos holds more than 50% of the stocks of said corporation and also is and always has been the president, manager, and treasurer thereof. Santos, in such triple capacity, through fault, neglect, and abandonment allowed its lumber concession to lapse and its properties and assets, among them machineries, buildings, warehouses, trucks, etc., to disappear, thus causing the complete ruin of the corporation and total depreciation of its stocks. Evangelista, et. al. therefore prays for judgment requiring Santos: (1) to render an account of his administration of the corporate affairs and assets: (2) to pay plaintiffs the value of t heir respective participation in said assets on the basis of the value of the stocks held by each of them; and (3) to pay the costs of suit. Evangelista, et. al. also ask for such other remedy as may be and equitable. The complaint does not give Evangelista, et. al.'s residence, but, but purposes of venue, alleges that Santos resides at 2112 Dewey Boulevard, corner Libertad Street, Pasay, province of Rizal. Having been served with summons at that place, Santos filed a motion for the dismissal of the complaint on the ground of improper venue and also on the ground that the complaint did not state a cause of action in favor of Evangelista, et. al. After hearing, the lower court rendered its order, granting the motion for dismissal. Reconsideration of the order was denied. Evangelista, et. al. appealed to the Supreme Court. Issue: Whether Evangelista, et. al. had the right to bring the action for damages resulting from mismanagement of the affairs and assets of the corporation by its principal officer, it being alleged that Santos' maladministration has brought about the ruin of the corporation and the consequent loss of value of its stocks. Held: The injury complained of is primarily to the corporation, so that the suit for the damages claimed should be by the corporation rather than by the stockholders. The stockholders may not directly claim those damages for themselves for that would result in the appropriation by, and the distribution among them of part of the corporate assets before the dissolution of the corporation and the liquidation of its debts and liabilities, something which cannot be legally done in view of section 16 of the Corporation Law, which provides that "No shall corporation shall make or declare any stock or bond dividend or any dividend whatsoever from the profits arising from its business, or divide or distribute its capital stock or property other than actual profits among its members or stockholders until

after the payment of its debts and the termination of its existence by limitation or lawful dissolution." But while it is to the corporation that the action should pertain in cases of this nature, however, if the officers of the corporation, who are the ones called upon to protect their rights, refuse to sue, or where a demand upon them to file the necessary suit would be futile because they are the very ones to be sued or because they hold the controlling interest in the corporation, then in that case any one of the stockholders is allowed to bring suit. But in that case it is the corporation itself and not the plaintiff stockholder that is the real property in interest, so that such damages as may be recovered shall pertain to the corporation. In other words, it is a derivative suit brought by a stockholder as the nominal party plaintiff for the benefit of the corporation, which is the real property in interest. Herein, Evangelista, et. al. have brought the action not for the benefit of the corporation but for their own benefit, since they ask that Santos make good the losses occasioned by his mismanagement and pay to them the value of their respective participation in the corporate assets on the basis of their respective holdings. Clearly, this cannot be done until all corporate debts, if there be any, are paid and the existence of the corporation terminated by the limitation of its charter or by lawful dissolution in view of the provisions of section 16 of the Corporation Law. It results that Evangelista, et. al.'s complaint shows no cause of action in their favor. Woodhouse vs. Halili [93 PHIL 527 # L-4811. July 31, 1953] Post under case digests, Civil Law at Tuesday, March 20, 2012 Posted by Schizophrenic Mind

Facts: The Plaintiff entered into an agreement with the defendant for the establishment of a partnership for bottling and distribution of Mission soft drinks. Before the partnership was actually established the defendant required the plaintiff to secure an exclusive franchise for the said venture. In behalf of the said partnership and upon obtaining the said exclusive franchise the defendant stipulated to pay the plaintiff 30% of the profits. The plaintiff sought to obtain the said exclusive franchise but was only given a temporary one, subject only to 30 days. The parties then proceeded with the signing of the agreement. The partnership was still not initiated, only the agreement to work with each other, with the plaintiff as manager and the defendant as financer, was established.

Together the two parties went to the US to formally sign the contract of franchise with Mission Dry Corporation. The defendant then found out about the temporary franchise right given to the plaintiff, different from the exclusive franchise rights they stipulated in their contract.

When the operations of the business began he was paid P 2,000 and was allowed the use of a car. But in the next month, the pay was decreased to P 1,000 and the car was withdrawn from him.

The plaintiff demanded the execution of the partnership, but the defendant excused himself, saying that there was no hurry to do so. The Court of First Instance ordered the defendant to render an accounting of the profits and to pay the plaintiff 15% of such amount. It also held that execution of the contract of partnership cannot be enforced upon the defendant and that fraud as alleged by the defendant was also not proved. Hence the present action.

Issues:

(1) Whether the representation of the plaintiff in saying that he had exclusive franchise rights rather than the actual temporary right he possessed invalidated the contract

(2) Whether the court may compel the defendant to execute the contract of partnership between the parties

(3) What will be the amount of damages to be paid to the plaintiff?

Held: The Decision of the Court of First Instance is affirmed with modification.

Fraud was undoubtedly employed by the plaintiff to secure the consent of the defendant to enter into the contract with him by representing himself as holder of exclusive franchise rights when in fact he only holds a temporary franchise right good for 30 days. The fraud employed was not such as to render the contract null and void but only such as to hold the plaintiff liable for damages. Such fraud is merely incidental (dolo incidental) and not the causal fraud (dolo causante) that is detrimental to a contract. It does not invalidate the contract since fraud was only employed to secure the 30% stipulated share from the partnership.

The parties cannot be compelled to enter into a contract of partnership. The law recognizes the liberty of an individual to do or not to do an act. The action falls within Acto Personalisimo (a very personal act) which courts may not compel compliance.

The 15% that the Trial court ordered the defendant to pay the plaintiff is deemed to be the appropriate and reasonable. Such amount was the spontaneous reaction of the defendant upon knowledge of the misrepresentation of the plaintiff and amounts to the virtual modification of their contract.

Moran vs Court of Appeals, 230 SCRA 799, GR No. 105836, March 7, 1994 Posted by Pius Morados on January 12, 2012 (Negotiable Instruments Checks) Facts: M who regularly purchased bulk fuel from P maintained 3 joint accounts with Citytrust Bank, namely: Current Account No. 1 (CA1), Savings Account No. 1 (SA1), and Savings Account No. 2 (SA2). M had a pre-authorized transfer (PAT) agreement with Citytrust wherein the former have written authority to the latter to automatically transfer funds from their SA1 to their CA1 at any time whenever the funds in their current account were insufficient to meet withdrawals from said current account. On December 12, 1983, M drew a check for P50, 576.00 payable to P. On December 13, 1983, M issued another check in the amount of P56, 090.00 in favor of the same.

On December 14, 1983, P deposited the 2 aforementioned check to its account with the PNB. In turn, PNB presented them for clearing and the record shows that on December 14, 1983, the accounts has insufficient funds (CA1 had a zero balance, while SA1 [covered by PAT] had an available balance of P26, 104.30 and SA2 had an available balance of P43, 268.39). Hence the checks were dishonoured. On December 15, 1983 at 10:00 AM, M went to the bank as was his regular practice and deposited in their SA2 the amounts of P10, 874.58 and P6, 754.25, and he deposited likewise in the SA1 the amounts of P5, 900.00, P35, 100.00 and 30.00. The amount of P40,000.00 was then transferred by him from SA2 to their CA1. At the same time, the amount of P66,666.00 was transferred from SA1 to the same current account through PAT agreement. Sometime on December 15 or 16, 1983 M was informed that that P refused to deliver their orders on a credit basis because the two checks they had previously issued were dishonored upon presentme nt for payment due to insufficiency of funds. The non-delivery of orders forced petitioners to stop business operations, allegedly causing them to suffer loss of earnings. On December 16 or 17, 1983, P got the signature of M on an application for a managers check so that the dishonoured checks could be redeemed and presented the checks in payment for the two dishonoured checks. On July 24, 1984, claimed P1,000,000.00 for moral damages. Issue: WON the bank is liable for damages for its refusal to pay a check on account of insufficient funds considering the fact that a deposit may be made later in the day. Held: No, Petitioners had no sufficient funds in their accounts when the bank dishonoured the checks in question. First, a check is a bill of exchange drawn on a bank payable on demand. Thus, a check is a written order addressed to a bank or persons carrying on the business of banking, by a party having money in their hands, requesting them to pay on presentment, to a person named therein or to bearer or order, a named sum of money. Second, the relationship between the bank and the depositor is that of a debtor and creditor . By virtue of the contract of deposit between the banker and its depositor, the banker agrees to pay checks drawn by the depositor provided that said depositor has money in the hands of the bank. Thirdly, where the bank possesses funds of the depositor, it is bound to honor his checks to the extent of the amount deposits. The failure of a bank to pay the check of a merchant or a trader, when the deposit is sufficient, entitles the drawer to substantial damages without any proof of actual damages. Conversely, a bank is not liable for its refusal to pay a check on account of insufficient funds, notwithstanding the fact that a deposit may be made later in the day. Before a bank depositor may maintain a suit to recover a specific amount form his bank, he must first show that he had on deposit sufficient funds to meet demand. Considering the clearing process adopted, it is clear that the available balance on December 14, 1983 was used by the bank in determining whether or not there was sufficient cash deposited to fund the two checks. When Ms checks were dishonored due to insufficiency of funds, the available balance of SA1 which was the subject of the PAT agreement was not enough to cover either of the two checks. On December 14, 1983, when PNB presented the checks for collection, the available balance for SA1 was only P26, 104.30 while CA1had no available balance. It was only on December 15, 1983 at around 10:00 AM that the necessary funds were deposited, which unfortunately was too late to prevent the dishonour of the checks.

HE LEYTE-SAMAR SALES CO., and RAYMUNDO TOMASSI, petitioners, vs.SULPICIO V. CEA, in his capacity as Judge of the Court of First Instance of Leyte and OLEGARIO LASTRILLA, respondents.In civil case No. 193 of the Court of First Instance of Leyte, which is a suit for damages by the Leyte-Samar Sales Co. (hereinafter called LESSCO) andRaymond Tomassi against the Far Eastern Lumber & Commercial Co. (unregistered commercial partnership hereinafter called FELCO), Arnold Hall,Fred Brown and Jean Roxas, rendered judgment against defendants jointly and severally for the amount of P31,589 plus cost on october 29, 1948.The Court of Appeals confirmed the award in November 1950, minus P2,000 representing attorney's fees mistakenly included. The decision havingbecome final, the sheriff sold at auction on June 9, 1951 to Robert Dorfe and Pepito Asturias "all the rights, interests, titles and participation" of thedefendants in certain buildings and properties described in the certificate, for a total price of eight thousand and one hundred pesos.On June 4, 1951 Olegario Lastrilla filed in the case a motion, wherein he claimed to be the owner by purchase on September 29, 1949, of all the"shares and interests" of defendant Fred Brown in the FELCO. Over the plaintiffs' objection the judge in his order of June 13, 1951, grantedLastrilla's motion by requiring the sheriff to retain 17 per cent of the money And on motion of Lastrilla, the court on August 14, 1951, modified itsorder of delivery and merely declared that Lastrilla was entitled to 17 per cent of the properties sold.Hence, this petition for "Certiorari and Prohibition with preliminary Injunction" praying for the additional writ of mandamus.issue:(a) whether or not Lastrilla is a partner of FELCO, having purchased the share and interest of defendant Fred Brown after CFI rendered anunfavorable judgment, but prior to the auction sale, hence he can claim to the proceeds of the sale?(b) whether or not there was grave abuse of discretion on the part of the judge in granting lastrilla's motion and ordering the delivery to him of the17% of the properties.ruling:(a) In the situation it we can conclude that on June 9, 1951 when the sale was effected of the properties of FELCO to Roberto Dorfe and PepitoAsturias, Lastilla was already a partner of FELCO. Now, does Lastrilla have any proper claim to the proceeds of the sale? If he was

a creditor of theFELCO, perhaps or maybe. But he was not. The partner of a partnership is not a creditor of such partnership for the amount of his shares. That istoo elementary to need elaboration.(c) On this score the respondent judge's action on Lastrilla's motion should be declared as in excess of jurisdiction, which even amounted to wantof jurisdiction, considering specially that Dorfe and Austrias, and the defendants themselves, had undoubtedly the right to be heard but theywere not notified.4Varied interest of necessity make Dorfe, Asturias and the defendants indispensable parties to the motion of Lastrilla.A valid judgment cannot be rendered where there is a want of necessary parties, and a court cannot properly adjudicate matters involved in a suit whennecessary and indispensable parties to the proceedings are not before it. In view of the foregoing, it is our opinion, and we so hold, that all ordersof the respondents judge requiring delivery of 17 per cent of the proceeds of the auction sale to respondent Olegario Lastrilla are null and void Tai Tong v Insurance G.R. No. L-55397 February 29, 1988 J. Gancayco

Facts: Azucena Palomo obtained a loan from Tai Tong Chuache Inc. in the amount of P100,000.00. To secure the payment of the loan, a mortgage was executed over the land and the building in favor of Tai Tong Chuache & Co. Arsenio Chua, representative of Thai Tong Chuache & Co. insured the latter's interest with Travellers Multi-Indemnity Corporation for P100,000.00 (P70,000.00 for the building and P30,000.00 for the contents thereof) Pedro Palomo secured a Fire Insurance Policy covering the building for P50,000.00 with respondent Zenith Insurance Corporation. On July 16, 1975, another Fire Insurance was procured from respondent Philippine British Assurance Company, covering the same building for P50,000.00 and the contents thereof for P70,000.00. The building and the contents were totally razed by fire. Based on the computation of the loss, including the Travellers Multi- Indemnity, respondents, Zenith Insurance, Phil. British Assurance and S.S.S. Accredited Group of Insurers, paid their corresponding shares of the loss. Complainants were paid the following: P41,546.79 by Philippine British Assurance Co., P11,877.14 by Zenith Insurance Corporation, and P5,936.57 by S.S.S. Group of Accredited Insurers Demand was made from respondent Travellers Multi-Indemnity for its share in the loss but the same was refused. Hence, complainants demanded from the other three (3) respondents the balance of each share in the loss in the amount of P30,894.31 (P5,732.79-Zenith Insurance: P22,294.62, Phil. British: and P2,866.90, SSS Accredited) but the same was refused, hence, this action. In their answers, Philippine British Assurance and Zenith Insurance Corporation denied liability on the ground that the claim of the complainants had already been waived, extinguished or paid. Both companies set up counterclaim in the total amount of P 91,546.79. SSS Accredited Group of Insurers informed the Commission that the claim of complainants for the balance had been paid in the amount in full. Travellers Insurance, on its part, admitted the issuance of a Policy and alleged defenses that Fire Policy, covering the furniture and building of complainants was secured by a certain Arsenio Chua and that the premium due on the fire policy was paid by Arsenio Chua. Tai Tong Chuache & Co. also filed a complaint in intervention claiming the proceeds of the fire Insurance Policy issued by respondent Travellers Multi-Indemnity. As adverted to above respondent Insurance Commission dismissed spouses Palomos' complaint on the ground that the insurance policy subject of the complaint was taken out by Tai Tong Chuache & Company, for its own interest only as mortgagee of the insured property and thus complainant as mortgagors of the insured property have no right of action against the respondent. It likewise dismissed petitioner's complaint in intervention in the following words: From the above decision, only intervenor Tai Tong Chuache filed a motion for reconsideration but it was likewise denied hence, the present petition.

Issue: WON Tai Tong had insurable interest

Held: Yes. Petition granted.

Ratio: Respondent advanced an affirmative defense of lack of insurable interest on the part of the petitioner that before the occurrence of the peril insured against, the Palomos had already paid their credit due the petitioner. However, they were never able to prove that Tai had a lack of insurable interest. Hence, the decision must be adverse against them. However respondent Insurance Commission absolved respondent insurance company from liability on the basis of the certification issued by the then Court of First Instance of Davao, Branch II, that in a certain civil action against the Palomos, Arsenio Lopez Chua stands as the complainant and not Tai Tong Chuache. From said evidence respondent commission inferred that the credit extended by petitioner to the Palomos secured by the insured property must have been paid. These findings was based upon a mere inference. The record of the case shows that the petitioner to support its claim for the insurance proceeds offered as evidence the contract of mortgage which has not been cancelled nor released. It has been held in a long line of cases that when the creditor is in possession of the document of credit, he need not prove non-payment for it is presumed. The validity of the insurance policy taken by petitioner was not assailed by private respondent. Moreover, petitioner's claim that the loan extended to the Palomos has not yet been paid was corroborated by Azucena Palomo who testified that they are still indebted to herein petitioner. Public respondent argues however, that if the civil case really stemmed from the loan granted to Azucena Palomo by petitioner the same should have been brought by Tai Tong Chuache or by its representative in its own behalf. From the above premise, respondent concluded that the obligation secured by the insured property must have been paid. However, it should be borne in mind that petitioner being a partnership may sue and be sued in its name or by its duly authorized representative. Petitioner's declaration that Arsenio Lopez Chua acts as the managing partner of the partnership was corroborated by respondent insurance company. Thus Chua as the managing partner of the partnership may execute all acts of administration including the right to sue debtors of the partnership in case of their failure to pay their obligations when it became due and demandable. Public respondent's allegation that the civil case flied by Arsenio Chua was in his capacity as personal creditor of spouses Palomo has no basis. The policy, then had legal force and effect.

G.R. No. L-2484 April 11, 1906 JOHN FORTIS,Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. GUTIERREZ HERMANOS,Defendants-Appellants. Hartigan, Rohde and Gutierrez, for appellants. W. A. Kincaid, for appellee. WILLARD, J.: Plaintiff, an employee of defendants during the years 1900, 1901, and 1902, brought this action to recover a balance due him as salary for the year 1902. He alleged that he was entitled, as salary, to 5 per cent of the net profits of the business of the defendants for said year. The complaint also contained a cause of action for the sum of 600 pesos, money expended by plaintiff for the defendants during the year 1903. The court below, in its judgment, found that the contract had been made as claimed by the plaintiff; that 5 per cent of the net profits of the business for the year 1902 amounted to 26,378.68 pesos, Mexican currency; that the plaintiff had received on account of such salary 12,811.75 pesos, Mexican currency, and ordered judgment against the defendants for the sum 13,566.93 pesos, Mexican currency, with interest thereon from December 31, 1904. The court also ordered judgment against the defendants for the 600 pesos mentioned in the complaint, and intereat thereon. The total judgment rendered against the defendants in favor of the plaintiff, reduced to Philippine currency, amounted to P13,025.40. The defendants moved for a new trial, which was denied, and they have brought the case here by bill of exceptions.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library

(1) The evidence is sufifcient to support the finding of the court below to the effect that the plaintiff worked for the defendants during the year 1902 under a contract by which he was to receive as compensation 5 per cent of the net profits of the business. The contract was made on the part of the defendants by Miguel Alonzo Gutierrez. By the provisions of the articles of partnership he was made one of the managers of the company, with full power to transact all of the business thereof. As such manager he had authority to make a contract of employment with the plaintiff.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library (2) Before answering in the court below, the defendants presented a motion that the complaint be made more definite and certain. This motion was denied. To the order denying it the defendants excepted, and they have assigned as error such ruling of the court below. There is nothing in the record to show that the defendants were in any way prejudiced by this ruling of the court below. If it were error it was error without prejudice, and not ground for reversal. (Sec. 503, Code of Civil Procedure.)chanrobles virtual law library (3) It is claimed by the appellants that the contract alleged in the complaint made the plaintiff a copartner of the defendants in the business which they were carrying on. This contention can not bo sustained. It was a mere contract of employnent. The plaintiff had no voice nor vote in the management of the affairs of the company. The fact that the compensation received by him was to be determined with reference to the profits made by the defendants in their business did not in any sense make by a partner therein. The articles of partnership between the defendants provided that the profits should be divided among the partners named in a certain proportion. The contract made between the plaintiff and the then manager of the defendant partnership did not in any way vary or modify this provision of the articles of partnership. The profits of the business could not be determined until all of the expenses had been paid. A part of the expenses to be paid for the year 1902 was the salary of the plaintiff. That salary had to be deducted before the net profits of the business, which were to be divided among the partners, could be ascertained. It was undoubtedly necessary in order to determine what the salary of the plaintiff was, to determine what the profits of the business were, after paying all of the expenses except his, but that determination was not the final determination of the net profits of the business. It was made for the purpose of fixing the basis upon which his compensation should be determined.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library (4) It was no necessary that the contract between the plaintiff and the defendants should be made in writing. (Thunga Chui vs. Que Bentec, 1 1 Off. Gaz., 818, October 8, 1903.)chanrobles virtual law library (5) It appearred that Miguel Alonzo Gutierrez, with whom the plaintiff had made the contract, had died prior to the trial of the action, and the defendants claim that by reasons of the provisions of section 383, paragraph 7, of the Code of Civil Procedure, plaintiff could not be a witness at the trial. That paragraph provides that parties to an action against an executor or aministrator upon a claim or demand against the estate of a deceased person can not testify as to any matter of fact occurring before the death of such deceased person. This action was not brought against the administrator of Miguel Alonzo, nor was it brought upon a claim against his estate. It was brought against a partnership which was in existence at the time of the trial of the action, and which was juridical person. The fact that Miguel Alonzo had been a partner in this company, and that his interest therein might be affected by the result of this suit, is not sufficient to bring the case within the provisions of the section above cited.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library (6) The plaintiff was allowed to testify against the objection and exception of the defendants, that he had been paid as salary for the year 1900 a part of the profits of the business. This evidence was competent for the purpose of corroborating the testimony of the plaintiff as to the existence of the contract set out in the complaint.chanroblesvirtualawlibrarychanrobles virtual law library (7) The plaintiff was allowed to testify as to the contents of a certain letter written by Miguel Glutierrez, one of the partners in the defendant company, to Miguel Alonzo Gutierrez, another partner, which letter was read to plaintiff by Miguel Alonzo. It is not necessary to inquire whether the court committed an error in admitting this evidence. The case already made by the plaintiff was in itself sufficient to prove the contract without reference to this letter. The error, if any there were, was not prejudicial, and is not ground for revesal. (Sec. 503, Code of Civil Procedure.)chanrobles virtual law library (8) For the purpose of proving what the profits of the defendants were for the year 1902, the plaintiff presented in evidence the ledger of defendants, which contained an entry made on the 31st of December, 1902, as follows: Perdidas y Ganancias ...................................... a Varios Ps. 527,573.66 Utilidades liquidas obtenidas durante el ano y que abonamos conforme a la proporcion que hemos establecido segun el convenio de sociedad. The defendant presented as a witness on, the subject of profits Miguel Gutierrez, one of the defendants, who testiffied, among other things, that there were no profits during the year 1902, but, on the contrary, that the company suffered considerable loss during that year. We do not think the evidence of this witnees sufficiently definite and certain to overcome the positive evidence furnished by the books of the defendants themselves.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library (9) In reference to the cause of action relating to the 600 pesos, it appears that the plaintiff left the employ of the defendants on the 19th of Macrh, 1903; that at their request he went to Hongkong, and was there for about two months looking after the business of the defendants in the matter of the repair of a certain steamship. The appellants in their brief say that the plaintiff is entitled to no compensation for his services thus rendered, because by the provisions of article 1711 of the Civil Code, in the absence of an agreement to the contrary, the contract of agency is supposed to be gratuitous. That article i not applicable to this case, because the amount of 600 pesos not claimed as compensation for services but as a reimbursment for money expended by the plaintiff in the business of the defendants. The article of the code that is applicable is article 1728.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library The judgment of the court below is affirmed, with the costs, of this instance against the appellants. After the expiration of twenty days from the date of this decision let final judgment be entered herein, and ten days thereafter let the case be remanded to the lower court for execution. So ordered.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library Arellano, C.J., Torres, Mapa, Johnson and Carson, JJ., concur.

Carmen Liwanag v. CA and People G.R. No. 114398 October 24, 1997 Romero, J. Facts: Liwanag asked Isidora Rosales to join her and Thelma Tagbilaran in the business of buyingand selling cigarettes. Under their agreement, Rosales would give the money needed tob u y t h e c i g a r e t t e s w h i l e L i w a n a g a n d T a b l i g a n w o u l d a c t a s h e r a g e n t s , w i t h a correspondin g 40% commission to her if the goods are sold; otherwise the money wouldbe returned to Rosales. Rosales gave several cash advances amounting to 633,650. Money was misappropriated. Rosales files a complaint of estafa against them. Issue: 1. WON the parties entered into a partnership agreement; 2. if in the negative, WONthe transaction is a simple loan Held: 1. No. Even assuming that a contract of partnership was indeed entered into by andbetween the parties, when money or property have been received by a partner for a specificpurpose and he later misappropriated it, such partner is guilty of estafa.2. No. In a contract of loan once the mone y is re ce ive d by the debtor, owne rship ove r the same is transferred. Being the owner, the borrower can dispose of it for whatever purposehe may deem proper Pascual and Dragon vs. CIR and CTA GRN- 78133 October 18, 1988 Gancayco, &. Facts: Petitioners bought to proceeds the following year. The 2 parcels were sold on 1970. Realizing profits from the sale petitioners filed capital gains tax. However, defendants assessed petitioners with deficiency tax corporate income taxes. Issue: Whether or not petitioners formed and unregistered partnership thereby assessed with corporate income tax. Ruling: By the contract of partnership two or more persons bind themselves to0 contribute money, property or industry to a common fund with the intention of dividing the profits among themselves. In the presents cases, there is no evidence that the petitioners into an agreement to contribute MPI to a common fund and that they intend to divide profits among themselves the petitioners purchased parcels of land and became co-owner thereof. Their transaction of selling the lots was an isolated case. The character of habituality peculiar to the business transactions for the purpose of gained was not present. The sharing of return does not in itself established a partnership whether or not the persons sharing theres have a joint or common right or interest in the property. There must be a clear intent to form partnership, the existence of juridical personality deferent from the individual partners, and the freedom of each party to transfer or assign the whole property. ROJAS VS. MAGLANAFACTS:Maglana and Rojas executed their Articles of Copartnership called Eastcoast DevelopmentEnterpises which had an indefinite term of existenceand was registered with the SEC and had a TimberLicense . One of the EDEs purposes was to apply orsecure timber and/or private forest lands and tooperate, develop and promote suchf o r e s t s r i g h t s a n d c o n c e s s i o n s . M s h a l m a n a g e t h e b u s i n e s s a f a i r s w h i l e R s h a l b e t h e l o g g i n g s u p e r i n t e n d e n t . A l p r o f i t s a n d losses shall be divided share and sharealike between them.Later on, the two availed the services of Pahamotangasindustrial partner and executed another articles of co-partnership with the latter. The purpose of thissecondp a r t n e r s h i p w a s t o h o l d a n d s e c u r e r e n e w a l o f t i m b e r l i c e n s e a n d t h e t e r m o f w h i c h w a s f i x e d t o 3 0 y e a r s . S t i l a t e r o n , t h e three executed a conditional sale of interest in the partnership wherein M and R shallpurchase the interest, shareand participation in thepartnership of P. It was also agreed that afterpayment of such including amount of loansecuredby P in favor of the partnership, the two shall becomeowners of all equipment contributed by P.After this,the two continued the partnership without anywritten agreement or reconstitution of their articlesof partnership.Subsequently, R entered into a managementcontract with CMS Estate Inc. M wrote him re:h i s c o n t r i b u t i o n t o t h e c a p i t a l i n v e s t m e n t s a s w e l a s h i s d u t i e s a s l o g g i n g s u p e r i n t e n d e n t . R r e p l i e d t h a t h e w i l n o t b e a b e l t o comply with bo th. M then told Rthat the latters share will just be 20% of the netprofits. Such was the sharing from 1957 to 1959without complaint or dispute. R took funds from thepartnership more than his contribution. Mnotified Rthat he dissolved the partnership. R filed an actionagainst M for the recovery of propertiesandaccounting of the partnership and damages.CFI:the partnership of M and R is after P retired isone of de facto and at will; the sharing of profits andlosses is onthe basis of actual

contributions; there isno evidence these properties were acquired by thepartnership funds thus it should not belong to it;neither is entitled to damages; the letter of M ineffect dissolvedt h e p a r n t e r s h p i s ;a e l o o f r e s c t o n c e s s o i n i s v a d i l a n d b n i d n i g a n d s h o u d l b e c o n s idered as Ms contribution; R must pay or turnover to the partnership the profits he received fromCMS and pay his personal account to the partnership;Mmust be paid 85k which he shouldve received butwas not paid to him and must be considered as hiscontribution.ISSUE:what is the nature of the partnership andlegal relationship of M-R after P retired from thesecond partnership? MayM unilaterally dissolve thepartnership?SC:There was no intention to dissolve the firstpartnership upon the constitution of the second aseverything else wasthe same except for the fact thatthey took in an industrial partner: they pursued thesame purposes, the capitalcontributions call for thesame amounts, all subsequent renewals of TimberLicense were secured in favor of thefirst partnership,all businesses were carried out under the registeredarticles.M and R agreed to purchase theinterest, share andparticipation of P and after, they became owners of the equipment contributed by P. Bothconsideredthemselves as partners as per their letters. It is not apartnership de facto or at will as it was existingandduly registered. The letter of M dissolving thepartnership is in effect a notice of withdrawal andmay be doneby expressly withdrawing even beforeexpiration of the period with or without justifiablecause. As tothe liquidation of the partnership it shall u o c t f k l n r a h s v i d e b g m . e d a R is not entitled toany profits as he failed to give theamount he had undertaken to contribute thus, hadbecome a debtor of thepartnership.M cannot be liable for damages as R abandoned thepartnership thru his acts and also took funds inanamount more than his contribution.Goguilay and Partnership vs. Sycip et. Al.Reyes J& L: &Facts:Tan Sin and Goguilay into a partnership in business of buying and selling real state properties. Partners stipulatedthat Tan Sin will be the managing partner and that heirs shall represent the deceased partnership incurred debtsand Tan Sin died, he was represents the deceased partner should the 10 years lifetime of the partnership has notyet expired. When the partnership incurred debts and Tan Sin will be managing partnership has not yet expired.

When the partnership incurred and Tan Sin died, he has represented by his widow. In order to satisfy thepartnerships debts the widow sold the properties to defendant. Goquilay opposed the sail assailing that widow hasno authority to do so, without his Kn.Issue:Whether or not the consent of the other partner way necessary to perfect the sale of the partnership properties.Riling:First, Goquilay is stopped from asserting that upon the death of Tan Sin, his management of partnership affairs hadalso been terminated.He was stopped in the same that after the death of Tan Sin, the partnership affairs from 1945 to 1949. It is onlywhen the sale with the defendant that the authority of the widow was questioned.It is a well settled rule that third persons. Are not bound in entering into a contract with any of the two partners,the ascertain whether or not his partner with whom the transaction is made has the consent of the other partner.The public need not make inquiries as to the agreement had between the partners. Its knowledge has enough thatit is contracting with the partnership which is represented by one of the managing partners HEIRS OF JOSE LIM, represented by ELENITO LIM vs. JULIET VILLA LIM G.R. No. 172690, March 3, 2010 Post under case digests, Civil Law at Friday, December 16, 2011 Posted by Schizophrenic Mind

HAD8J5EKCNKC NACHURA, J.:

FACTS: Petitioners are the heirs of the late Jose Lim (Jose). They filed a Complaint for Partition, Accounting and Damages against respondent Juliet Villa Lim (respondent), widow of the late Elfledo Lim (Elfledo), who was the eldest son of Jose and Cresencia.

Petitioners alleged that Jose was the liaison officer of Interwood Sawmill in Cagsiay, Mauban, Quezon. Sometime in 1980, Jose, together with his friends Jimmy Yu (Jimmy) and Norberto Uy (Norberto), formed a partnership to engage in the trucking business. Initially, with a contribution of P50,000.00 each, they purchased a truck to be used in the hauling and transport of lumber of the sawmill. Jose managed the operations of this trucking business until his death on August 15, 1981. Thereafter, Jose's heirs, including Elfledo, and partners agreed to continue the business under the management of Elfledo. The shares in the partnership profits and income that formed part of the estate of Jose were held in trust by Elfledo, with petitioners' authority for Elfledo to use, purchase or acquire properties using said funds. Petitioners alleged that Elfledo was never a partner or an investor in the business and merely supervised the purchase of additional trucks using the income from the trucking business of the partners.

On May 18, 1995, Elfledo died, leaving respondent as his sole surviving heir. Petitioners claimed that respondent took over the administration of the aforementioned properties, which belonged to the estate of Jose, without their consent and approval. Claiming that they are co-owners of the properties, petitioners required respondent to submit an accounting of all income, profits and rentals received from the estate of Elfledo, and to surrender the administration thereof. Respondent refused; thus, the filing of this case.

Respondent traversed petitioners' allegations and claimed that Elfledo was himself a partner of Norberto and Jimmy. Respondent also alleged that when Jose died in 1981, he left no known assets, and the partnership with Jimmy and Norberto ceased upon his demise. Respondent also stressed that Jose left no properties that Elfledo could have held in trust. Respondent maintained that all the properties involved in this case were purchased and acquired through her and her husbands joint efforts and hard work, an d without any participation or contribution from petitioners or from Jose.

ISSUE:

Whether

or

not

partnership

exists.

HELD: YES. A partnership exists when two or more persons agree to place their money, effects, labor, and skill in lawful commerce or business, with the understanding that there shall be a proportionate sharing of the profits and losses among them. A contract of

partnership is defined by the Civil Code as one where two or more persons bind themselves to contribute money, property, or industry to a common fund, with the intention of dividing the profits among themselves.

The following circumstances tend to prove that Elfledo was himself the partner of Jimmy and Norberto: 1) Cresencia testified that Jose gave Elfledo P50,000.00, as share in the partnership, on a date that coincided with the payment of the initial capital in the partnership; (2) Elfledo ran the affairs of the partnership, wielding absolute control, power and authority, without any intervention or opposition whatsoever from any of petitioners herein; (3) all of the properties were registered in the name of Elfledo; (4) Jimmy testified that Elfledo did not receive wages or salaries from the partnership, indicating that what he actually received were shares of the profits of the business; and (5) none of the petitioners, as heirs of Jose, thealleged partner, demanded periodic accounting from Elfledo during his lifetime. Gregorio Ortega, Tomas del Castillo, Jr. and Benjamin Bacorro v. CA, SEC and Joaquin Misa G.R. No. 109248 July 3, 1995 Vitug, J. Facts: Ortega, then a senior partner in the law firm Bito, Misa, and Lozada withdrew in said firm. He filed with SEC a petition for dissolution and liquidation of partnership. S EC e n banc rule d tha t w i thdrawal of Misa from the fi rm had dissolve d the partne rship .Re ason: since it is partne rship a t w ill , the la w firm could be dissolved by any pa rtne r a t anytime, such as by withdrawal therefrom, regardless of good faith or bad faith, since nopartner can be forced to continue in the partnership against his will. Issue: 1. WON the partnership of Bito, Misa & Lozada (now Bito, Lozada, Ortega & Castillo)is a partnership at will; 2. WON the withdrawal of Misa dissolved the partnership regardlessof his good or bad faith; Held: 1. Yes. The partnership agreement of the firm provides that [t]he partnership shallcontinue so long as mutually satisfactory an d upon the death or legal incapacity of one of the partners, shall be continued by the surviving partners.2 . Y e s . A n y o n e o f t h e p a r t n e r s m a y , a t h i s s o l e p l e a s u r e , d i c t a t e a d i s s o l u t i o n o f t h e partnership at will (e.g. by way of withdrawal of a partner). He must, however, act in goodfaith, not that the attendance of bad faith can prevent the dissolution of the partnership butthat it can result in a liability for damages. SANTOS VS REYES 368 SCRA 261 FACT S- Petitioner Fernando Santos, Respondent Nieves Reyes and Meliton Zabatstarted a lending Business venture together proposed by Nieves. It wasagreed on the Articles of Agreement that petitioner will get 70% of theprofits and Nieves and Zabat would earn 15% each.- Nievas introduced Gragera (chairman of Monte Maria DevelopmentCorporation) to petitioner, and sought short term loans for its membersand with an agreement that Monte Maria will be entitled to P1.31commission per thousand paid daily. Nieves acted as bookkeeper whileher husband Arsenio acted as credit investigator.- Gragera complained that his commissions were inadequately remitted.This prompt petitioner to file a complaint against respondent allegedly intheir capacities as employees of petitioner, with having misappropriatedfunds. ISSUEWhether or not the business relationship between petitioner andrespondent was one of partnershipHELDYES- Nieves herself provided the initiative in the lending activities with MonteMaria.The fact that in their Articles of Agreement, the parties agreed to dividethe profits of a lending business in a 70 -15-15, manner, with petitioner getting the lions share proved the establishment of a partnership, even when the other parties to the agreement were given separatecompensation as bookkeeper and creditor investigator.- By the contract of partnership, two or more persons bind themselves tocontribute money, property or industry to a common fund, with theintention of dividing the profits among themselves. (Art. 1767 NCC) MORAN VS CA133 SCRA 88 FACT S- Pecson and Moran entered into an agreement whereby both wouldcontribute P15,000 each for the purpose of printing 95,000 posters whichfeatures the delegates of the Constitutional Convention. Pecson gaveMoran P10,000 pesos for which the latter issued a receipt.- Out of the 95,000 copies agreed upon only 2,000 copies were printed. Itcan be said that the venture failed.- Pecson filed with the CFI an action for recovery of a sum of a sum of money and demanded for the return of his contribution of P10,000 andshare in the profits that the partnership would have earned, and paymentof unpaid commission, among others. ISSUEWhether or not Pecson can demand for his share of the profits andpayment of unpaid commission of the businessHELD- Being a contract of partnership, each partner must share in the profitsand losses of the venture. That is the essence of a partnership.- Even with an assurance made by one of the partners that they would earna huge amount of profits, in the absence of fraud, the other partnercannot claim a right to recover the highly speculative profits. It is a rarebusiness venture guaranteed to give 1005 profits.- Article 1797 NCC, the losses and profits shall be distributed in conformitywith the agreement. If only the share of each partner in the profits hasbeen agreed upon, the share of each in the losses shall be in the sameproportion. NAVARRO VS CA222 SCRA 675