Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Rule 1-3 Compilation

Uploaded by

Carl MontemayorOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Rule 1-3 Compilation

Uploaded by

Carl MontemayorCopyright:

Available Formats

Rule 1: General Provisions 1. G.R. No.

L-51767 June 29, 1982 LETICIA CO, assisted by her husband MUI YUK KONG, in substitution of CITADEL INSURANCE & SURETY CO., INC., plaintiff-appellee, vs. PHILIPPINE NATIONAL BANK, defendant-appellant. Facts: Standard executed a real estate mortgage in favor of PNB over titles of land as collateral and a chattel mortgage to its personal properties for a consideration which totals to P4, 296,803.56. When Standard failed to pay its obligation, both the real estate as well as the chattel was foreclosed. Meantime, Citadel wrote a letter to PNB stating its desire to redeem the property covered by TCT No. 54474, it being the alleged assignee of the right of redemption of Standard with respect only to said property but the bank refused since the offer of Citadel was much lower than what the bank acquired from the foreclosure. Citadel then filed for an instant petition for the redemption of the said property and that PNB to accept it payment. Issue: WON PNB is bound to accept payment which is considerably lower than what it acquired from the foreclosure. Held: No. The liberal posture adopted by the Supreme Court in permitting a tender of redemption for less than the full claims of the creditor (PNB) and allowing the redemptioner time to pay up the balance of the claim is made in exercise of the Supreme Courts equity jurisdiction which can be exercised to prevent injustice from a technical adherence to the letter of the law.When a bank grants a loan, secured by any collateral, what is of uppermost consideration to such lender is the borrowers capacity to pay according to the terms stipulated, and not really the acquisition of the collateral, if only to maintain the banks liquidity position as conveniently as possible. Acquired assets generally add to liquidity problems of banks. The foreclosure of the security is a measure of last resort, hence when by the exercise of the right of redemption, the bank can recover the money it has loaned, nothing could be more proper than to allow the borrower to retain his property. Of course, peculiar instances are naturally excepted. That is why this decision cannot be invoked as a precedent for other parties not exactly similarly situated as the appellee in this case. Should there be any thought that Our resolution of this case is not strictly according to legal principles, let everyone be reminded that this Court has inherent equity jurisdiction it can always exercise in settings attended by unusual circumstances to prevent manifest injustice that could result from bare technical adherence to the letter of the law and imprecise jurisprudence under it. Consequently, it is but just and proper that PNB should be paid the full amount of P3,366,546.42 without any interest as of March 11, 1976, when it refused a redemption legally and validly tendered. On the other hand, the amount of P1,621,970.00 tendered by CITADEL on March 5, 1976 and which was deposited in a savings account, drawing interest apparently less than 12% p. a., in the name of PNB by order of the trial court should be computed to have earned legal in terest or 12% p. a., compounded annually, since March 11, 1976, provided however that should such amount including the compounded interest at 12% p. a., so earned be less than P3,366,546.42, petitioner herein should pay PNB such difference, and provided, on the other hand, that with this arrangement, PNB does not have to account to CITADEL/LETICIA CO for any of the rentals it had earned from the time it took possession of the property. In the final analysis, instead of PNB losing P1,744,576.42, under strict technical legal reasoning, as explained above, applying hereto the principle of unjust enrichment, which We deem in the peculiar circumstances at this instant case to be the fairest way of resolving this controversy, it would still be paid by petitioner a certain amount, not to mention what must be quite substantial and considerable, the rentals the said bank it has earned, which it does not have to account for.

While a redemptioner may be considered to have made a valid tender of payment by less than the creditors total claims, it will be inequitable that the PNB shall not get a full satisfaction of its credit.However, We are persuaded that all such considerations would render the result of this case short of what appears to be substantial justice in the light of the situation on hand. It strikes Us as rather unconscionable that by a literal application of the law and perphaps due to a mistake in the amount of the bid made by PNB, the bank would not get full satisfaction of its credit. Indeed, there would be unjust enrichment on the part of the debtor-mortgagor in such an eventuality. Our sense of justice cannot permit such iniquitous advantage.

2. [A.M. No. RTJ-93-1031. January 28, 1997] RODRIGO B. SUPENA, petitioner, vs. JUDGE ROSALIO G. DE LA ROSA, respondent. FACTS: On April 1, 1993, mortgagee BAID decided to extrajudicially foreclose the Real Estate Mortgage[1] executed by mortgagor PQL in the former's favor. Maningas, the Clerk of Court and Ex-Officio Sheriff of Manila, issued a Notice of Extrajudicial Sale, scheduling the public auction sale on May 26, 1993 at 10:00 o'clock a.m. in front of the City Hall Building, Manila. Supena, President of Mortgagee BPI Agricultural Development Bank charges respondent de la Rosa with gross ignorance of the law for issuing an unlawful Order, in Foreclosure Case. The Order in effect held in abeyance the public auction sale, on the basis of a mere Ex-Parte Motion to Hold Auction Sale in Abeyance filed by Mortgagor, PQL Realty Incorporated. Complainant avers that it was issued without the proper case being filed and without the benefit of notice and hearing, or even an injunction bond from which the mortgagee may seek compensation and restitution for the damages it may suffer by reason of the improper cancellation of the auction sale. The only ground relied upon is that the parties have agreed to hold the foreclosure proceedings in Makati and not in Manila and so the complainant submits that the actuations of respondent judge in granting the ex-parte motion of mortgagor were without basis and highly suspicious. ISSUE: WON respondent judge is liable of gross ignorance of the law for using as reference the Act No. 3135, as opposed to Rule 4 of the Revised Rules of Court. HELD: YES. We find the respondent judge culpable as charged. Any judge, worthy of the robe he dons, ought to know that different laws apply to different kinds of sales under our jurisdiction. Since the real property subject of the sale is situated in Felix Huertas Street, Sta. Cruz, Manila. Thus, by express provision of Section 2, the sale cannot be made outside of Manila. Respondent judge, however, refers to the venue stipulation in the Loan Agreement signed by the parties to the effect that, "Any action or suit brought under this Agreement or any other documents related hereto shall be instituted in the proper courts of Makati x x x. The failure of respondent to recognize this is an utter display of ignorance of the law to which he swore to maintain professional competence. Written stipulations as to venue are either mandatory or permissive. In interpreting stipulations, inquiry must be made as to whether or not the agreement is restrictive in the sense that the suit may be filed only in the place agreed upon or merely permissive in that the parties may file their suits not only in the place agreed upon but also in the places fixed by the rules. In the absence of qualifying or restrictive words, they should be considered merely as an agreement on additional forum, not as limiting venue to the specified place. They are not exclusive but, rather permissive.

It has been said that when the law transgressed is elementary, the failure to know or observe it constitutes gross ignorance of the law. In this case, a mere reference by respondent judge to Act No. 3135, as opposed to Rule 4 of the Revised Rules of Court, as well as the Deed of the Real Estate Mortgage itself, would dictate that there is no justification whatsoever for him to hold in abeyance the extrajudicial foreclosure sale scheduled on May 26, 1993 in front of the City Hall of Manila. A judge owes it to the public and to the legal profession to know the very law he is supposed to apply to a given controversy as mandated by the Code of Judicial Conduct. Unfortunately, respondent judge, instead of inspiring faith and confidence in the administration of justice, committed a rank disservice to its cause when he issued the Order based on the inapplicable provisions of the Rules of Court.

3. MANCHESTER DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION, ET AL., petitioners, vs. COURT OF APPEALS, CITY LAND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION, STEPHEN ROXAS, ANDREW LUISON, GRACE LUISON and JOSE DE MAISIP, respondents. FACTS: Petitioners contends that the Court of Appeals erred in that the filing fee should be levied by considering the amount of damages sought in the original complaint. The present case is an action for torts and damages and specific performance with prayer for temporary restraining order. The prayer is for the issuance of a writ of preliminary prohibitory injunction during the pendency of the action against the defendants' announced forfeiture of the sum of P3 Million paid by the plaintiffs for the property in question, to attach such property of defendants, to order defendants to execute a contract of purchase and sale of the subject property and annul defendants' illegal forfeiture of, ordering defendants to pay plaintiff's damages as well as the tender of payment. The amount of damages sought is not specified in the prayer although the body of the complaint alleges the total amount of over P78 Million as damages suffered by plaintiff. The complaint was considered as primarily an action for recovery of ownership and possession of a parcel of land. The damages stated were treated as merely to the main cause of action. After this Court issued an order on October 15, 1985 ordering the re- assessment of the docket fee in the present case and other cases that were investigated, on November 12, 1985 the trial court directed plaintiffs to rectify the amended complaint by stating the amounts which they are asking for. It was only then that plaintiffs specified the amount of damages in the body of the complaint in the reduced amount of P10,000,000.00. 7 Still no amount of damages were specified in the prayer. Said amended complaint was admitted. ISSUE: WON the court acquires jurisdiction over the case. HELD: NO. As reiterated in the Magaspi case the rule is well-settled "that a case is deemed filed only upon payment of the docket fee regardless of the actual date of filing in court . Thus, in the present case the trial court did not acquire jurisdiction over the case by the payment of only P410.00 as docket fee. Neither can the amendment of the complaint thereby vest jurisdiction upon the Court. For an legal purposes there is no such original complaint that was duly filed which could be amended. Consequently, the order admitting the amended complaint and all subsequent proceedings and actions taken by the trial court are null and void. The basis of assessment of the docket fee should be the amount of damages sought in the original complaint and not in the amended complaint. The Court frowns at the practice of counsel who filed the original complaint in this case of omitting any specification of the amount of damages in the prayer although the amount of over P78 million is alleged in the body of the complaint. This is clearly intended for no other purpose than to evade the payment of the correct filing fees if not to mislead the docket clerk in the assessment of the filing fee. The Court acquires jurisdiction over any case only upon the payment of the prescribed docket

fee. An amendment of the complaint or similar pleading will not thereby vest jurisdiction in the Court, much less the payment of the docket fee based on the amounts sought in the amended pleading. The ruling in the Magaspi case in so far as it is inconsistent with this pronouncement is overturned and reversed.

4. G.R. Nos. 79937-38 February 13, 1989 SUN INSURANCE OFFICE, LTD., (SIOL), E.B. PHILIPPS and D.J. WARBY, petitioners, vs. HON. MAXIMIANO C. ASUNCION, Presiding Judge, Branch 104, Regional Trial Court, Quezon City and MANUEL CHUA UY PO TIONG, respondents. FACTS: Private respondent filed a complaint in the Regional Trial Court of Quezon City for the refund of premiums and the issuance of a writ of preliminary attachment against petitioner SIOL. In the body of the original complaint, the total amount of damages sought amounted to about P50 Million. In the prayer, the amount of damages asked for was not stated. The amount of only P210.00 was paid for the docket fee. On January 23, 1986, private respondent filed an amended complaint wherein in the prayer it is asked that he be awarded no less than P10,000,000.00 as actual and exemplary damages but in the body of the complaint the amount of his pecuniary claim is approximately P44,601,623.70. Said amended complaint was admitted and the private respondent was reassessed the additional docket fee of P39,786.00 based on his prayer of not less than P10,000,000.00 in damages, which he paid. On April 24, 1986, private respondent filed a supplemental complaint alleging an additional claim of P20,000,000.00 in damages so that his total claim is approximately P64,601,620.70. On October 16, 1986, private respondent paid an additional docket fee of P80,396.00. After the promulgation of the decision of the respondent court on August 31, 1987 wherein private respondent was ordered to be reassessed for additional docket fee, and during the pendency of this petition, on April 28, 1988, private respondent paid an additional docket fee of P62,132.92. Although private respondent appears to have paid a total amount of P182,824.90 for the docket fee considering the total amount of his claim in the amended and supplemental complaint amounting to about P64,601,620.70, petitioner insists that private respondent must pay a docket fee of P257,810.49. ISSUE: WON the court acquires jurisdiction over a case when the correct and proper docket fees has not been paid. Ruling: NO. It is not simply the filing of the complaint or appropriate initiatory pleading, but the payment of the prescribed docket fee, that vests a trial court with jurisdiction over the subject-matter or nature of the action. Where the filing of the initiatory pleading is not accompanied by payment of the docket fee, the court may allow payment of the fee within a reasonable time but in no case beyond the applicable prescriptive or reglementary period. The same rule applies to permissive counterclaims, third party-claims and similar pleadings, which shall not be considered filed until and unless the filing fee prescribed therefor is paid. The court may also allow payment of said fee within a reasonable time but also in no case beyond its applicable prescriptive or reglementary period.

In the present case, a more liberal interpretation of the rules is called for considering that, unlike Manchester, private respondent demonstrated his willingness to abide by the rules by paying the additional docket fees as required. The promulgation of the decision in Manchester must have had that sobering influence on private respondent who thus paid the additional docket fee as ordered by the respondent court. It triggered his change of stance by manifesting his willingness to pay such additional docket fee as may be ordered. Nevertheless, petitioners contend that the docket fee that was paid is still insufficient considering the total amount of the claim. This is a matter which the clerk of court of the lower court and/or his duly authorized docket clerk or clerk in-charge should determine and, thereafter, if any amount is found due, he must require the private respondent to pay the same.

5. G.R. Nos. 88075-77 December 20, 1989 MAXIMO TACAY, PONCIANO PANES and ANTONIA NOEL, petitioners, vs. REGIONAL TRIAL COURT OF TAGUM Davao del Norte, Branches 1 and 2, Presided by Hon. Marcial Fernandez and Hon. Jesus Matas, respectively, PATSITA GAMUTAN, Clerk of Court, and GODOFREDO PINEDA, respondents. Facts: Respondent Pineda instituted an action for recovery of possession against Tacay, Panes and Noel at the RTC of Tagum Davao del Norte. Facts show that Pineda is the owner of the land measuring 790sq meters and that the previous owner allowed the defendants to occupy such by mere tolerance. When Pineda came in need for the use of the land, he demanded them to vacate the land and to pay rentals but the latter refused. Pineda then instituted a complaint praying that he be declared the owner of the land and that the defendants pay monthly rentals since February 1987 as well as nominal, actual and moral damages and attorneys fees and that Pineda be granted further reliefs and remedies. The defendants then filed for dismissal alleging that the Trial court did not acquire jurisdiction over the case for the reason that the complaint failed to specify the amounts of damages and for failure to allege the basic requirement as to the assessed value of the subject lot in dispute. The motion to dismiss was later on denied by Judge Matas. The motions to dismiss in Civil Cases 2211 and 2209 were also denied declaring that since the "action at bar is for Reivindicatoria, Damages and Attorney's fees ... (d)efinitely this Court has the exclusive jurisdiction," (b) that the claims for actual, moral and nominal damages "are only one aspect of the cause of action," and (c) because of absence of specification of the amounts claimed as moral, nominal and actual damages, they should be "expunged from the records." The defendants later on filed a joint petition for certiorari, prohibition and mandamus with prayer for TRO praying that the orders be annulled on the ground of grave abuse of discretion and reasserts that the court did not acquire jurisdiction. Issue: WON the court acquired jurisdiction. Held: Yes. The petition of the defendants should be therefore dismissed. The motion for dismissal fails to demonstrate any grave abuse of discretion on the part of the respondent Judges in rendering the Orders complained of or, for that matter, the existence of any proper cause for the issuance of the writ of mandamus. On the contrary, the orders appear to have correctly applied the law to the admitted facts. The actions are not basically for the recovery of sums of money. They are principally for recovery of possession of real property, in the nature of an accion publiciana. Determinative of the court's jurisdiction in this type of actions is the nature thereof, not the amount of the damages

allegedly arising from or connected with the issue of title or possession, and regardless of the value of the property. A real action-may be commenced and prosecuted without an accompanying claim for actual, moral, nominal or exemplary damages; and such an action would fall within the exclusive, original jurisdiction of the Regional Trial Court. Batas Pambansa Bilang 129 provides that Regional Trial Courts shall exercise exclusive original jurisdiction inter alia over "all civil actions which involve the title to, or possession of, real property, or any interest therein, except actions for forcible entry into and unlawful detainer of lands or buildings, original jurisdiction over which is conferred upon Metropolitan Trial Courts, 14 Municipal Trial Courts, and Municipal Circuit Trial Courts." The rule applies regardless of the value of the real property involved, whether it be worth more than P20,000.00 or not, infra. The rule also applies even where the complaint involving realty also prays for an award of damages; the amount of those damages would be immaterial to the question of the Court's jurisdiction.

6. G.R. No. 88421 January 30, 1990 AYALA CORPORATION, LAS PIAS VENTURES, INC., and FILIPINAS LIFE ASSURANCE COMPANY, INC., petitioners vs. THE HONORABLE JOB B. MADAYAG, PRESIDING JUDGE, REGIONAL TRIAL COURT, NATIONAL CAPITAL JUDICIAL REGION, BRANCH 145 and THE SPOUSES CAMILO AND MA. MARLENE SABIO, respondents. FACTS: Private respondents paid only the amount of P l,616 as docket fees instead of P13,061 based on the assessed value of the real properties and that he failed to specify the amount of exemplary damages sought. Private respondent then filed against petitioners an action for specific performance with damages in the Regional Trial Court of Makati. Petitioners filed a motion to dismiss on the ground that the lower court has not acquired jurisdiction over the case as private respondents failed to pay the prescribed docket fee and to specify the amount of exemplary damages both in the body and prayer of the amended and supplemental complaint. The trial court denied the motion as well as the motion for reconsideration of petitioner. However, the contention of petitioners is that since the action concerns real estate, the assessed value thereof should be considered in computing the fees pursuant to Section 5, Rule 141 of the Rules of Court. Such rule cannot apply to this case which is an action for specific performance with damages although it is in relation to a transaction involving real estate. Pursuant to Manchester, the amount of the docket fees to be paid should be computed on the basis of the amount of damages stated in the complaint. The trial court denied the motion stating that the determination of the exemplary damages is within the sound discretion of the court and that it would be unwarrantedly presumptuous on the part of the private respondents to fix the amount of exemplary damages being prayed for. Hence this petition. ISSUE: WON the payment of filing fees in an action for specific performance with damages must be specified to acquire jurisdiction. HELD: YES. The amount of any claim for damages, therefore, arising on or before the filing of the complaint or any pleading, should be specified. While it is true that the determination of certain damages as exemplary or corrective damages is left to the sound discretion of the court, it is the duty of the parties claiming such damages to specify the amount sought on the basis of which the court may make a proper determination, and for the proper assessment of the appropriate docket fees. The exception contemplated as to claims not specified or to claims although specified are

left for determination of the court is limited only to any damages that may arise after the filing of the complaint or similar pleading for then it will not be possible for the claimant to specify nor speculate as to the amount thereof. The amended and supplemental complaint in the present case, therefore, suffers from the material defect in failing to state the amount of exemplary damages prayed for. As ruled in Tacay the trial court may either order said claim to be expunged from the record as it did not acquire jurisdiction over the same or on motion, it may allow, within a reasonable time, the amendment of the amended and supplemental complaint so as to state the precise amount of the exemplary damages sought and require the payment of the requisite fees therefor within the relevant prescriptive period. 7. G.R. No. 125683 March 2, 1999 EDEN BALLATAN and SPS. BETTY MARTINEZ and CHONG CHY LING, petitioners, vs. COURT OF APPEALS, GONZALO GO, WINSTON GO, LI CHING YAO, ARANETA INSTITUTE OF AGRICULTURE and JOSE N. QUEDDING, respondents. Facts: This is a petition for review on certiorari of the decision of the Court of Appeals dated March 25, 1996 in CA-G.R. CV No. 32472 entitled "Eden Ballatan., et. al., plaintiffs-appellees v. Gonzalo Go and Winston Go, appellants and third-party plaintiffs-appellants v. Li Ching Yao, et. al., third-party defendants." The case arose from a dispute over a 42 sq meters land owned by the petitioners. When petitioner constructed her house, she found out that the adjoining house of Winston Go encroached a part of her lot. Respondent Go, however, claimed that his house, including its fence and pathway, were built within the parameters of his father's lot. A relocation survey was then made by AIA and found out that the property of petitioner was indeed encroached by Gos house. Eden demanded that the latter dismantle its improvements but he refused. Petitioner then filed an action for recovery and defendant Go countered and filed a third party-complaint against AIA and Li Ching Yao but the court decided in favor of the petitioner and ordered Go to demolish the improvements. Aggrieved, Go filed for appeal but the decision of the lower court was affirmed and the third-party complaint against AIA was dismissed but the case against Li Ching Yao was reinstated. Issue: WON the court erred in not dismissing the third party complaint due to non-payment of filing fees. Held: No. the rule in this jurisdiction is that when an action is filed in court, the complaint must be accompanied by the payment of the requisite docket and filing fees.The third-party complaint in the instant case arose from the complaint of petitioners against respondents Go. The complaint filed was for accion publiciana, i.e., the recovery of possession of real property which is a real action. The rule in this jurisdiction is that when an action is filed in court, the complaint must be accompanied by the payment of the requisite docket and filing fees. In real actions, the docket and filing fees are based on the value of the property and the amount of damages claimed, if any. If the complaint is filed but the fees are not paid at the time of filing, the court acquires jurisdiction upon full payment of the fees within a reasonable time as the court may grant, barring prescription. Rule 2: Cause of Action

Rule 2: Cause of Action 1. UNION GLASS & CONTAINER CORPORATION and CARLOS PALANCA, JR., in his capacity as President of Union Glass & Container Corporation, petitioners, vs. THE SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION and CAROLINA HOFILEA, respondents. FACTS: Private respondent Carolina Hofilea is a stockholder of Pioneer Glass Manufacturing Corporation Pioneer Glass had obtained various loan accommodations from the Development Bank of the Philippines [DBP], and also from other local and foreign sources which DBP guaranteed. As security for said loan accommodations, Pioneer Glass mortgaged and/or assigned its assets, real and personal, to the DBP, in addition to the mortgages executed by some of its corporate officers over their personal assets Pioneer Glass suffered serious liquidity problems such that it could no longer meet its financial obligations with DBP, it entered into a dacion en pago agreement with the latter. Hofilea filed a complaint before the respondent Securities and Exchange Commission based on the alleged illegality of the aforesaid dacion en pago. petitioners moved for dismissal of the case on the ground that the SEC had no jurisdiction over the subject matter or nature of the suit. SEC granted the motion to dismiss for lack of jurisdiction. However, it was reversed ISSUE: WON the SEC has jurisdiction. RULING: No. Since petitioner Union Glass has no intra-corporate relation with either the complainant or the DBP, its joinder as party-defendant in SEC Case No. 2035 brings the cause of action asserted against it outside the jurisdiction of the respondent SEC. As heretofore pointed out, petitioner Union Glass is involved only in the first cause of action of Hofileas complaint in SEC Case No, 2035. While the Rules of Court, which applies suppletorily to proceedings before the SEC, allows the joinder of causes of action in one complaint, such procedure however is subject to the rules regarding jurisdiction, venue and joinder of 9 parties. Since petitioner has no intra-corporate relationship with the complainant, it cannot be joined as party-defendant in said case as to do so would violate the rule or jurisdiction. Hofileas complaint against petitioner for cancellation of the sale of the glass plant should therefore be brought separately before the regular court But such action, if instituted, shall be suspended to await the final outcome of SEC Case No. 2035, for the issue of the validity of the dacion en pago posed in the last mentioned case is a prejudicial question, the resolution of which is a logical antecedent of the issue involved in the action against petitioner Union Glass. Thus, Hofileas complaint against the latter can only prosper if final judgment is rendered in SEC Case No. 2035, annulling the dacion en pago executed in favor of the DBP.

2. G.R. No. 123555 January 22, 1999 PROGRESSIVE DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION, INC., petitioner, vs. COURT OF APPEALS and WESTIN SEAFOOD MARKET, INC. respondents Facts: Petitioner leased to private, respondent Westin Seafood Market, Inc., a parcel of land with a commercial building thereon located at Aranet Center, Cubao, Quezon City, for a period of nine (9) years and three (3) months The contract contained, among others, the following pertinent terms and conditions: 1. Effect of violations: 1. Contract shall be terminated without resorting to court actions if the lessee violates conditions. 2. Termination of lease: LESSEE shall immediately vacate and redeliver physical possession of the leased premises if he fails to comply with the provisions. Private respondent failed to pay rentals despite several demands by petitioner. Non-payment of rentals constituted breach of their contract; petitioner on 31 October 1992 repossessed the leased premises, inventoried the movable properties and scheduled auction for the sale of the movables. Respondent then filed a complaint for forcible entry and prayer for TRO and preliminary injunction. Private respondent did not comply with its undertaking to deposit with the bank the rentals. Instead, with the forcible entry case still pending with the MeTC, private respondent instituted another action for damages against petitioner with the RTC. Petitioner filed a motion, to dismiss the damage suit on the ground of litis pendencia and forum shopping. Judge then denied petitioners motion to dismiss and granted TRO Petitioner filed with the CA certiorari and prohibition on the ground of grave abuse of discretion in allowing forum shopping. The CA dismissed on the ground of failure by the petitioner to file for MR on the Judges order which it said to be a prerequisite to the institution of certiorari and prohibition. It also found that the elements of litis pendencia were lacking to justify the dismissal of the action for damages with the RTC because despite the pendency of the forcible entry case with the MeTC the only damages recoverable thereat were those caused by the loss of the use and occupation of the property and not the kind of damages being claimed before the RTC which had no direct relation to loss of material possession. It clarified that since the damages prayed for in the amended complaint with the RTC were those caused by the alleged high-handed manner with which petitioner reacquired possession of the leased premises and the sale of private respondent's movables found therein, the RTC and not the MeTC had jurisdiction over the action of damages. movables found therein, the RTC and not the MeTC had jurisdiction over the action of damages. Issue: WON the judge committed grave abuse of discretion when it took cognizance of the action for damages and injunction despite the pendency of forcible entry case in MetC. Held: Yes. All cases for forcible entry or unlawful detainer shall be filed before the Municipal Trial Court which shall include not only the plea for restoration of possession but also all claims for damages and costs arising therefrom. This is consistent with the principle laid down in Sec. 1, par. (e), of Rule 16 of the Rules of Court which states that the pendency of another action between the same parties for the same cause is a ground for dismissal of an action. Res adjudicata requires that there must be between the

action sought to be dismissed and the other action the following elements: (a) identity of parties or at least such as representing the same interest in both actions; (b) identity of rights asserted and relief prayed for, the relief being founded on the same facts; and, (c) the identity in the two (2) preceding particulars should be such that any judgment which may be rendered on the other action will, regardless of which party is successful, amount to res adjudicata in the action under consideration. It is likewise basic under Sec. 3 of Rule 2 of the Revised Rules of Court, as amended, that a party may not institute more than one suit for a single cause of action. Under Sec. 4 of the same Rule, if two or more suits are instituted on the basis of the same cause of action, the filing of one or a judgment upon the merits in any one is available as a ground for the dismissal of the other or others. "Cause of action" is defined by Sec. 2 of Rule 2 as the act of omission by which a party violates a right of another. These premises obtaining, there is no question at all that private respondent's cause of action in the forcible entry case and in the suit for damages is the alleged illegal retaking of possession of the leased premises by the lessor, petitioner herein, from which all legal reliefs arise. Simply stated, the restoration of possession and demand for actual damages in the case before the MeTC and the demand for damages with the RTC both arise from the same cause of action, i.e., the forcible entry by petitioner into the least premises. 3. G.R. No. 138497 January 16, 2002 IMELDA RELUCIO, petitioner, vs. ANGELINA MEJIA LOPEZ, respondent. Facts: Herein private respondent Angelina Mejia Lopez (plaintiff below) filed a petition for "APPOINTMENT AS SOLE ADMINISTRATIX OF CONJUGAL PARTNERSHIP OF PROPERTIES, FORFEITURE, against defendant Alberto Lopez and petitioner Imelda Relucio. In the petition, respondent averred that she was the lawful wife of herein defendant, Alberto Lopez, and that the latter abandoned her and their children depriving them support and arrogated to himself alone the exclusive controal and administration of their properties together with his concubine, herein petitioner, Imelda Relucio. However, petitioner filed a motion to dismiss on the ground that the respondent has no cause of action agaisnt her. The RTC denied said motion. When the case was elevated in the CA, the case was likiwise dismiss. Hence, this appeal.

Issue: Whether or not cause of action exists against the petitioner and the same was alleged in the complaint Held: No. A cause of action is an act or omission of one party the defendant in violation of the legal right of the other."The elements of a cause of action are: (1) a right in favor of the plaintiff by whatever means and under whatever law it arises or is created; (2) an obligation on the part of the named defendant to respect or not to violate such right; and (3) an act or omission on the part of such defendant in violation of the right of the plaintiff

or constituting a breach of the obligation of the defendant to the plaintiff for which the latter may maintain an action for recovery of damages. In order to sustain a motion to dismiss for lack of cause of action, the complaint must show that the claim for relief does not exist, rather than that a claim has been merely defectively stated or is ambiguous, indefinite or uncertain. Hence, to determine the sufficiency of the cause of action is should be determined by the allegation in the complaint. In Part Two on the "Nature of [the] Complaint," respondent Angelina Mejia Lopez summarized the causes of action alleged in the complaint below. The complaint is by an aggrieved wife against her husband. Nowhere in the allegations does it appear that relief is sought against petitioner. Respondent's causes of action were all against her husband. The first cause of action is for judicial appointment of respondent as administratrix of the conjugal partnership. Petitioner is a complete stranger to this cause of action. The second cause of action is for an accounting "by respondent husband." The accounting of conjugal partnership arises from or is an incident of marriage. Petitioner has nothing to do with the marriage between respondent Alberto J. Lopez. Hence, no cause of action can exist against petitioner on this ground.

Rule 3: Parties to Civil Action 1. G.R. No. L-53856 August 21, 1980

OSCAR VENTANILLA ENTERPRISES CORPORATION, petitioner, vs. HON. ALFREDO M. LAZARO, Presiding Judge of the Court of First Instance of Manila, Branch XXXV; CLERK OF COURT and DEPUTY SHERIFF of the Court of First Instance of Manila, Branch XXXV; EMPEROR FILMS INT'L. (PHILS.), INC. and RICARDO C. VENTANILLA, respondents. FACTS: Petitioner Oscar Ventanilla Enterprises Corporation seeks to restrain the enforcement of the judgment of the Court of First Instance of Manila in "Emperor Films Int'l. (Phils.), Inc. vs. Broadway Theater". Similar petition was again filed in the Court of Appeals by petitioner but was dismissed because it cannot issue the writs of certiorari and prohibition. Moreover, petitioner, not being a party in the case, cannot ask for a review of any order issued in that case. In a compromise agreement, Ventanilla promised to pay in installment the debt and agreed that, in case of default execution shall immediately issue. ISSUE: WON the action can be brought against a juridical person. HELD: No. Under Section 1 of Rule 3 of the Rules of Court, only natural or juridical persons, or entities authorized by law may be parties in a civil action. Hence, a complaint is defective where defendant is not a natural or juridical person. It is at once obvious that the complaint in the said case is defective because the defendant is not a natural or juridical person. However, that defect was cured by the answer of Ventanilla, the lessee of the Broadway Theater, who admitted having issued three postdated checks and by the compromise agreement executed between the plaintiff and him, who, in effect, substituted himself for defendant "Broadway theater". Thus the lower court rendered judgment in accordance with the compromise agreement. The court holds that Ventanilla Corporation is entitled to the writ of prohibition.

2. G.R. No. 108015. May 20, 1998 CRISTINA DE KNECHT and RENE KNECHT, petitioners, vs. HON. COURT OF APPEALS FACTS: -Petitioners De Knecht was the owner of a parcel of land where 8 houses were built -The State sought to expropriate the property. - The SC held that the choice of area is arbitrary and annulled the expropriation case. - The City Treasurer of Pasay discovered that the Knechts failed to pay real estate taxes on the property. The City Treasurer sold the property at public auction. - Petitioners failed to redeem the property within one year from the date of sale. - The Register of Deeds issued TCT No. 86670 in the names of Sangalang and Babiera. The Knechts, who were in possession of the property, allegedly learned of the auction sale only by the time they received the orders of the land registration courts.

- BP Blg. 340 authorizing the national government to expropriate certain properties in Pasay City for the EDSA Extension was passed. The property of the Knechts was part of those expropriated under B.P. Blg. 340. -The de Knechts filed a case before the Regional Trial Court praying for reconveyance, annulment of the tax sale and the titles of the Babieras and Sangalangs. The Knechts based their action on lack of the required notices to the tax sale. It was dismissed -The State instituted a case for determination of just compensation -The Knechts filed a "Motion for Intervention and to Implead Additional Parties" -The trial court issued an order denying the Knechts' "Motion for Intervention and to Implead Additional Parties." Issue: WON Petitioner should be included in expropriation case. Ruling: NO. The term owner when employed to statutes relating to eminent domain refers to those who have lawful interest in the property to be condemned When the expropriation case was filed, the case for reconveyance was dismissed with finality. The petitioners lost whatever right or colourable title they had to the property. The Knetchts had no legal interest in the property by the time the expropriation proceedings were instituted.

3. G.R. No. 106194 January 28, 1997 SANTIAGO LAND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION, petitioner, vs. The HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS and the HEIRS OF NORBERTO J. QUISUMBING, respondents Facts: Norberto J. Quisumbing brought an action against the Philippine National Bank to enforce an alleged right to redeem certain real properties foreclosed by the Philippine National Bank. Quisumbing brought the suit as assignee of the mortgagor, Komatsu Industries (Phils.), Incorporated. With notice of pending civil action, Santiago Land Devt Corp purchased from PNB one of the properties subject to litigation for 90 million. Petitioner SLDC filed a motion to intervene, with its answer in intervention attached, alleging that it was the transferee pendente lite of the property and that any adverse ruling or decision, which might be rendered against PNB, would necessarily affect it (petitioner). In its attached answer, SLDC, aside from adopting the answer filed by PNB, raised as affirmative defenses the trial court's lack of jurisdiction based on the alleged failure of plaintiff Quisumbing to pay the docket fee and Quisumbing's alleged lack of cause of action against the PNB due to the invalidity of the deed of assignment to him. Quisumbing opposed SLDC's motion for intervention. He argued that SLDC's interest in the subject property was a mere contingency or expectancy, which was dependent on any judgment which might be rendered for or against PNB as transferor. The court then granted petitioners motion for intervention and directed the substitution of heirs in view of Norberto Quisumbings demise and submitted for resolution PNBs motion to dismiss. SLDC then served interrogatories upon respondents and moved for the production, inspection and copying of certain documents. Private respondents filed a motion to quash or disallow the interrogatories but it was denied by the court.

Issue: WON petitioner, as transferee pendente lite of the property in litigation has a right to intervene. Held: No. Rule 12, 2 of the Rules of Court provides: Sec. 2. Intervention. A person may, before or during a trial be permitted by the court, in its discretion, to intervene in an action, if he has legal interest in the matter in litigation, or in the success of either of the parties, or an interest against both, or when he is so situated as to be adversely affected by a distribution or other disposition of property in the custody of the court or of an officer thereof. The question is whether this provision applies to petitioner in view of Rule 3, 20 governing transfers of interest pendente lite such as was alleged in the trial court by petitioner. This provision reads: Sec. 20. Transfer of interest. In case of any transfer of interest, the action may be continued by or against the original party, unless the court upon motion directs the person to whom the interest is transferred to be substituted in the action or joined with the original party. In applying the rule on transfer of interest pendente lite (Rule 3, 20) rather than the rule on intervention (Rule 12, 2), the Court of Appeals stated: While it may be that respondent SLDC has a legal interest in the subject matter of the litigation, its interest as transferee pendente lite is different from that of an intervenor. Section 2 of Rule 12 refers to all other persons or entities whose legal interests stand to be affected by a litigation, but it does not cover a transferee pendente lite because such transferee is already specifically governed by Section 20 of Rule 3. Otherwise, Section 20 of Rule 3 on transferees pendente lite would be rendered ineffectual and useless. Since it specifically covers transferees pendente lite, any such transferee cannot just disregard said provision and instead, opt to participate as an intervenor when it is more convenient for it to do so. Indeed, there has never been a rule, authority or decision holding that a transferee pendente lite has the option to avail of either Rule 3, Section 20 or Rule 12, Section 2. It has been consistently held that a transferee pendente lite stands in exactly the same position as its predecessor-in-interest, that is, the original defendant. . . . However, should the transferee pendente lite choose to participate in the proceedings, it can only do so as a substituted defendant or as a joint party-defendant. The transferee pendente lite is a proper but not an indispensable party as it would in any event be bound by the judgment against his predecessorin-interest. This would be true even if respondent SLDC is not formally included as a partydefendant through an amendment of the complaint. As such, the transferee pendente lite is bound by the proceedings already had in the case before the property was transferred to it The purpose of Rule 12, 2 on intervention is to enable a stranger to an action to become a party to protect his interest and the court incidentally to settle all conflicting claims. On the other hand, the purpose of Rule 3, 20 is to provide for the substitution of the transferee pendente lite precisely because he is not a stranger but a successor-in-interest of the transferor, who is a party to the action. As such, a transferee's title to the property is subject to the incidents and results of the pending litigation and is in no better position than the vendor in whose shoes he now stands.

4. G.R. No. 102900 October 2, 1997 MARCELINO ARCELONA, TOMASA ARCELONA-CHIANG and RUTH ARCELONA, represented by their attorney-in-fact, ERLINDA PILE, petitioners, vs. COURT OF APPEALS, REGIONAL TRIAL COURT OF DAGUPAN CITY, Branch XL, and MOISES FARNACIO, respondents.

Facts: Herein petitioners are co owners of the fish pond subject of this case, while the private respondent was the care taker of said property placed by the lessor. The controversy arose when the contract of lease entered into by the petitioners and their lessor expired. When the property was turned over to the petitioners, private respondent instituted Civil Case D-7240 for "peaceful possession, maintenance of security of tenure plus damages, with motion for the issuance of an interlocutory order" against the petitioners. However, not all co-owners named in the title were impleaded in the complaint. Thereafter, the trial court rendred a decision in favor of the respondent ordering the petitioners to give back the possession of the property and all rights pertaining to him. Subsequently, when said judgement became final and executory, herein petitioners filed an appeal with the Court of Appeals asking said court to annul the jugdement on the ground that not all co owners were impleaded and consequesently said jugdment is void.

Issue: Whether or not co-owners pro indiviso of a real property are indispensable parties and therefore, should be impleaded in the complaint. Held: Yes. Rule 3, Section 7 of the Rules of Court, defines indispensable parties as parties-in-interest without whom there can be no final determination of an action. As such, they must be joined either as plaintiffs or as defendants. The general rule with reference to the making of parties in a civil action requires, of course, the joinder of all necessary parties where possible, and the joinder of all indispensable parties under any and all conditions, their presence being a sine qua non for the exercise of judicial power. 31 It is precisely "when an indispensable party is not before the court (that) the action should be dismissed." 32 The absence of an indispensable party renders all subsequent actions of the court null and void for want of authority to act, not only as to the absent parties but even as to those present. Petitioners are co-owners of a fishpond. Private respondent does not deny this fact, and the Court of Appeals did not make any contrary finding. The fishpond is undivided; it is impossible to pinpoint which specific portion of the property is owned by Olanday, et al. and which portion belongs to petitioners. Thus, it is not possible to show over which portion the tenancy relation of private respondent has been established and ruled upon in Civil Case D-7240. Indeed, petitioners should have been properly impleaded as indispensable parties.

5. GR 126000. October 7, 1998 METROPOLITAN WATERWORKS AND SEWERAGE SYSTEM (MWSS), petitioner, vs. COURT OF APPEALS, HON. PERCIVAL LOPEZ, AYALA CORPORATION and AYALA LAND, INC., respondents. FACTS: On 1965, petitioner MWSS leased 128 hectares of its land to CHGCCI for 25 years with a stipulation allowing the latter to exercise a right of first refusal should the subject property be made open for sale. The terms and conditions of CHGCCIs purchase was nonetheless subject to presidential approval where the President expressed his approval of the sale. He then directed MWSS to negotiate the cancellation of this lease agreement between MWSS and CHGCCI. However, MWSS general manager, Ilustre, informed CHGCCI that the property was up for sale, and that as per their contract, CHGCCI had the preferential right to buy said property. Hence, the property was purchased, and Pres. Marcos later on approved this sale. Then, BoT of MWSS also approved the sale by passing a resolution. CHGCCI sold the land to Ayala. AYALA then developed the land into a prime residential area 10 years later, MWSS filed an action against CHGCCI and Ayala in RTC praying for the declaration of nullity of the MWSS-CHGCCI sales agreement. RTC dismissed the petition while CA affirmed. Hence, this petition for certiorari with SC. Respondent court denies the petitions for writ of certiorari and affirms the order of the lower court dismissing the complaint against Ayala. This prompted MWSS to file another petition for review where it holds that Ilustre was never given the authority by the BoT to enter into the initial agreement, and therefore, the sale of the property was null and void. ISSUE: Whether or not the suit shall prosper without the indispensable parties. HELD: No. There is no denying that petitioner MWSS' action against herein respondents for the recovery of the subject property now converted into a prime residential subdivision would ultimately affect the proprietary rights of the many lot owners to whom the land has already been parceled out. They should have been included in the suit as parties-defendants, for. "it is well established that owners of property over which reconveyance is asserted are indispensable parties without whom no relief is available and without whom the court can render no valid judgment." Being indispensable parties, the absence of these lot-owners in the suit renders all subsequent actions of the trial court null and void for want of authority to act, not only as to the absent parties but even as to those present. Thus, when indispensable parties are not before the court, the action should be dismissed. Assuming that Ilustre was not given the ample authority to enter into the agreement, this infirmity was cured by ratification. So settled is the precept that ratification can be made by the corporate board either expressly or impliedly. Assuming their truth, show that MWSS consented to the sale, only that such consent was purportedly vitiated by undue influence or fraud. Therefore, the rules on prescription will operate. Even if petitioner MWSS asked for the declaration of nullity of these contracts, the prayers will not be controlling as only the factual allegations in the complaint determine relief. The assumption that the allegations in the complaint establish the absolute nullity of the assailed contracts an hence imprescriptible, the complaint can still be dismissed on the ground of laches which is different from prescription.

6. ALLIED AGRI-BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT CO., INC., petitioner, vs. COURT OF APPEALS and CHERRY VALLEY FARMS LIMITED, respondents.

FACTS: -respondent Cherry Valley Farms Limited (CHERRY VALLEY), a foreign company based in England, filed against petitioner Allied Agri-Business Development Co. Inc. (ALLIED) a complaint with the Regional Trial Court of Makati City for the collection of sum of money alleging that petitioner purchased in ten (10) separate orders and received from respondent CHERRY VALLEY several duck hatching eggs and ducklings and ALLIED did not pay the total purchase price of 51,245.12 despite repeated demands ALLIED filed an answer and contended that: (a) private respondent CHERRY VALLEY lacked the capacity to sue The trial court rendered a decision against the petitioners. CA affirmed the lower courts decision. ISSUE: Won Private respondent has capacity to sue. Ruling: yes. We cannot sustain the allegation that the respondent Cherry Valley, being an unlicensed foreign corporation lacked the legal capacity to institute the suit in the trial court for recovery of money claims. In fact, petitioner is estopped from challenging or questioning the personality of a corporation after having acknowledge the same by entering a contract with it 7. G.R. No. 127833 January 22, 1999 TEODORO URQUIAGA and MARIA AGUIRRE, petitioners, vs. THE COURT OF APPEALS, VICENTE CASES and ANITA CRISOSTOMO, respondents Facts: Spouses Cases and Crisostomo are registered owners of a 26,152 square meters situated in Sicayab, Dipolog City, covered by Original Certificate of Title No. P-16635 which was subdivided into 2 lots Workers of the petitioners entered the lot and gathered nipa palms therefrom and claimed that the petitioners owned the property and that its parents owned it since time immemorial. During Barangay conciliation, petitioner Urquiaga questioned the validity of private respondents' title by ascribing actual fraud in its acquisition. Respondents then filed for TRO because petitioner built a dike on the property. The court then enjoined Uriquaga to undertake any activity that would alter the status of the lot. The court then ruled in favor of Cases and Crisostomo declaring them as true owners of the lot. The petitioners then appealed to the SC alleging that respondents acquired the lots through fraud and misrepresentation. They further contend that their possession ripened into ownership since their predecessor-in-interest possessed such since World War II.

Issue: 1. WON petitioners are the true owners of the land for having possession for a long period of time. 2. WON the court may institute reversion proceeding on the ground of fraud and misrepresentation. Held:

1. No. Petitioners' claim of ownership over Lot No. 6532-B stands on quicksand and its alleged roots do not actually exist. The parents of petitioner Maria Aguirre could not have possessed the subject lot for a long duration because as early as January 1923 when the cadastral survey was started they did not claim any right much less interest thereto. Neither were they claimants in the cadastral case. On the other hand, respondents' avowal of ownership is supported by a certificate of title issued on account of a sales patent duly awarded by the Director of Lands. 2. No. It is only the State which may institute reversion proceedings under Sec. 101 of the Public 16 Land Act considering the finding that the subject lot was public land at the time of the sales application. This law provides Sec. 101. All actions for reversion to the Government of lands of the public domain or improvements thereon shall be instituted by the Solicitor General or the officer acting in his stead, in the proper courts, in the name of the Republic of the Philippines.

8. Benavidez vs CA 9. G.R. No. 162788. July 28, 2005 Spouses JULITA DE LA CRUZ and FELIPE DE LA CRUZ, petitioners, vs. PEDRO JOAQUIN, respondent. FACTS: Respondent Joaquin filed a complaint against petitioners for the recovery of possession and ownership, the cancellation of title, and damages. He alleged that he had obtained a loan of P9,000, payable after (5) years where he supposedly executed a Deed of Sale for parcel of land. The parties also executed another document entitled Kasunduan. Where respondent claimed that the Kasunduan showed the Deed of Sale to be actually an equitable mortgage. Spouses De la Cruz contended that it was merely an accommodation to allow the repurchase of the property, which he failed to exercise. RTC issued a Decision in his favor. The trial court declared that it was a sale with a right of repurchase and that respondent had made a valid tender of payment to exercise his right of repurchase. Accordingly, petitioners were required to reconvey the property upon his payment. CA sustained the trial court's ruling. While on it's 2004 Resolution, CA denied reconsideration and ordered a substitution by legal representatives, in view of respondents death on December 24, 1988. Hence, this Petition. ISSUE: WON the trial court lost jurisdiction over the case upon the death of the respondent. HELD: No. When a party to a pending action dies and the claim is not extinguished, the Rules of Court require a substitution of the deceased. The procedure is specifically governed by Section 16 of Rule 3, which reads thus: Death of a party; duty of counsel. Whenever a party to a pending action dies, and the claim is not thereby extinguished, it shall be the duty of his counsel to inform the court within thirty (30) days after such death of the fact thereof, and to give the name and address of his legal representative or representatives. Failure of counsel to comply with this duty shall be a ground for disciplinary action. The heirs of the deceased may be allowed to be substituted for the deceased, without requiring the appointment of an executor or administrator and the court may appoint a guardian ad litem for the minor heirs. The Rules require the legal representatives of a dead litigant to be substituted as parties to a litigation. This requirement is necessitated by due process. Thus, when the rights of the legal

representatives of a decedent are actually recognized and protected, noncompliance or belated formal compliance with the Rules cannot affect the validity of the promulgated decision. After all, due process had thereby been satisfied. The general rule notwithstanding, a formal substitution by heirs is not necessary when they themselves voluntarily appear, participate in the case, and present evidence in defense of the deceased. Thus there being no violation of due process, the issue of substitution cannot be upheld as a ground to nullify the trial courts Decision.

10. G.R. No. 166302. July 28, 2005 LOTTE PHIL. CO., INC., petitioner, vs. ERLINDA DELA CRUZ, LEONOR MAMAUAG, LOURDES CAUBA, JOSEPHINE DOMANAIS, ARLENE CAGAYAT, AMELITA YAM, VIVIAN DOMARAIS, MARILYN ANTALAN, CHRISTOPHER RAMIREZ, ARNOLD SAN PEDRO, MARISSA SAN PEDRO, LORELI JIMENEZ, JEFFREY BUENO, CHRISTOPHER CAGAYAT, GERARD CABILES, JOAN ENRIQUEZ, JOSEPH DE LA CRUZ, NELLY CLERIGO, DULCE NAVARETTE, ROWENA BELLO, DANIEL RAMIREZ, AILEEN BAUTISTA and BALTAZAR FERRERA, respondents.

FACTS: 7J Maintenance and Janitorial Services (7J) entered into a contract with Petitio ner LOTTE to provide manpower for needed maintenance, utility, janitorial and other services to the latter. Petitoner dispensed with their services allegedly due to the expiration/termination of the service contract by petitioner with 7J respondents filed a labor complaint against both Lotte and 7J, for illegal dismissal, regularization, th payment of corresponding backwages and related employment benefits, 13 month pay, service incentive leave, moral and exemplary damages and attorneys fees based on total judgment award. Labor Arbiter rendered judgment declaring 7J as employer of respondents. The arbiter also found 7J guilty of illegal dismissal. Respondents appealed to the National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC) praying that Lotte be declared as their direct employer because 7J is merely a labor-only contractor. It was denied. They filed a petition for certiorari in the Court of Appeals against the NLRC and Lotte, insisting that their employer is Lotte and not 7J. the Court of Appeals reversed and set aside the rulings of the Labor Arbiter and the NLRC. The Court of Appeals declared Lotte as the real employer of respondents and that 7J who engaged in labor-only contracting was merely the agent of Lotte. Lottes motion for reconsideration was denied

ISSUE: WON 7j should be impleaded

RULING: Yes,

An indispensable party is a party in interest without whom no final determination can be had of an action, and who shall be joined either as plaintiffs or defendants. The joinder of indispensable parties is mandatory. The presence of indispensable parties is necessary to vest the court with jurisdiction, which is the authority to hear and determine a cause, the right to act in a case. Thus, without the presence of indispensable parties to a suit or proceeding, judgment of [19] a court cannot attain real finality. The absence of an indispensable party renders all subsequent actions of the court null and void for want of authority to act, not only as to the absent [20] parties but even as to those present. In the case at bar, 7J is an indispensable party. It is a party in interest because it will be affected by the outcome of the case. The Labor Arbiter and the NLRC found 7J to be solely liable as the employer of respondents. The Court of Appeals however rendered Lotte jointly and severally liable with 7J who was not impleaded by holding that the former is the real employer of respondents. Plainly, its decision directly affected 7J.

11. G.R. No. 110318 August 28, 1996 COLUMBIA PICTURES, INC., ORION PICTURES CORPORATION, PARAMOUNT PICTURES CORPORATION, TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX FILM CORPORATION, UNITED ARTISTS CORPORATION, UNIVERSAL CITY STUDIOS, INC., THE WALT DISNEY COMPANY, and WARNER BROTHERS, INC., petitioners, vs. COURT OF APPEALS, SUNSHINE HOME VIDEO, INC. and DANILO A. PELINDARIO, respondents. Facts: Complainants filed a complaint with the NBI for violation of PD 49 (anti- piracy) against Sunshine Home Video. A search warrant was then served against respondent and the agents found and seized various tapes of duly copyrighted motion pictures belonging to complainants. The respondents then averred that that being foreign corporations, petitioners should have such license to be able to maintain an action in Philippine courts. They allege that as foreign corporations doing business in the Philippines, Section 133 of Batas Pambansa Blg. 68, or the Corporation Code of the Philippines, denies them the right to maintain a suit in Philippine courts in the absence of a license to do business. Consequently, they have no right to ask for the issuance of a search warrant. Issue: WON the complainants have the right to maintain suit in Philippine courts. Held: No. Sec. 133. Doing business without a license. No foreign corporation transacting business in the Philippines without a license, or its successors or assigns, shall be permitted to maintain or intervene in any action, suit or proceeding in any court or administrative agency of the Philippines; but such corporation may be sued or proceeded against before Philippine courts or administrative tribunals on any valid cause of action recognized under Philippine laws. The obtainment of a license prescribed by Section 125 of the Corporation Code is not a condition precedent to the maintenance of any kind of action in Philippine courts by a foreign corporation. However, under the aforequoted provision, no foreign corporation shall be permitted to transact business in the Philippines, as this phrase is understood under the Corporation Code, unless it shall have the license required by law, and until it complies with the law intransacting business here, it shall not be permitted to maintain any suit in local courts. Among the grounds for a motion to dismiss under the Rules of Court are lack of legal capacity to sue and that the complaint states no cause of action. Lack of legal capacity to sue means that the plaintiff is not in the exercise of his civil rights, or does not have the

necessary qualification to appear in the case, or does not have the character or representation he claims. On the other hand, a case is dismissible for lack of personality to sue upon proof that the plaintiff is not the real party in interest, hence grounded on failure to state a cause of action. The term lack of capacity to sue should not be confused with the term lack of personality to sue. While the former refers to a plaintiffs general disability to sue, such as on account of minority, insanity, incompetence, lack of juridical personality or any other general disqualifications of a party, the latter refers to the fact that the plaintiff is not the real party in interest. Correspondingly, the first can be a ground for a motion to dismiss based on the ground of lack of legal capacity to sue; whereas the second can be used as a ground for a motion to dismiss based on the fact that the complaint, on the face thereof, evidently states no cause of action.

You might also like

- Bonifacia Sy Po Vs CTADocument2 pagesBonifacia Sy Po Vs CTACarl Montemayor50% (2)

- Preliminary Injunction CASESDocument11 pagesPreliminary Injunction CASESCarl MontemayorNo ratings yet

- Interpleader and Declaratory Relief CasesDocument16 pagesInterpleader and Declaratory Relief CasesCarl MontemayorNo ratings yet

- Judiciary Santiago Vs Bautista Facts: Sero Elementary SchoolDocument7 pagesJudiciary Santiago Vs Bautista Facts: Sero Elementary SchoolCarl MontemayorNo ratings yet

- Minutes Five PercenterDocument2 pagesMinutes Five PercenterCarl MontemayorNo ratings yet

- Ang Tibay Vs CIRDocument1 pageAng Tibay Vs CIRCarl MontemayorNo ratings yet

- GGGDocument1 pageGGGCarl MontemayorNo ratings yet

- Certiorari 64 and 65Document10 pagesCertiorari 64 and 65Carl MontemayorNo ratings yet

- Notes For 9165Document3 pagesNotes For 9165Carl MontemayorNo ratings yet

- Airline Pilots Vs CIR - LABORDocument2 pagesAirline Pilots Vs CIR - LABORCarl Montemayor100% (1)

- De La Cruz Vs Capinpin - EvidenceDocument2 pagesDe La Cruz Vs Capinpin - EvidenceCarl MontemayorNo ratings yet

- Barbizon Vs Laguesma - LaborDocument1 pageBarbizon Vs Laguesma - LaborCarl MontemayorNo ratings yet

- UST Faculty Union Vs Bitonio - Self OrganizationDocument1 pageUST Faculty Union Vs Bitonio - Self OrganizationCarl MontemayorNo ratings yet

- Republic Vs HizonDocument1 pageRepublic Vs HizonCarl MontemayorNo ratings yet

- Ty Vs People - Consideration NegoDocument2 pagesTy Vs People - Consideration NegoCarl MontemayorNo ratings yet

- Filipino Society Vs Tan - CopyrightDocument2 pagesFilipino Society Vs Tan - CopyrightCarl MontemayorNo ratings yet

- Domingo Vs Robles - Presumption of AuthenticityDocument1 pageDomingo Vs Robles - Presumption of AuthenticityCarl MontemayorNo ratings yet

- Bonifacia Sy Po Vs CTADocument2 pagesBonifacia Sy Po Vs CTACarl Montemayor50% (2)

- Legislative History - TrademarkDocument1 pageLegislative History - TrademarkCarl MontemayorNo ratings yet

- Domingo Vs Robles - Presumption of AuthenticityDocument1 pageDomingo Vs Robles - Presumption of AuthenticityCarl MontemayorNo ratings yet

- Fitness Vs CIR - Powers of The CIRDocument3 pagesFitness Vs CIR - Powers of The CIRCarl MontemayorNo ratings yet

- BPI Vs CASA - Forged SignaturesDocument2 pagesBPI Vs CASA - Forged SignaturesCarl MontemayorNo ratings yet

- Republic Vs GonzalesDocument2 pagesRepublic Vs GonzalesCarl MontemayorNo ratings yet

- Bank of America Vs PRCI - Incomplete, DeliveredDocument2 pagesBank of America Vs PRCI - Incomplete, DeliveredCarl MontemayorNo ratings yet

- CIR Vs Ariete - TaxationDocument2 pagesCIR Vs Ariete - TaxationCarl MontemayorNo ratings yet

- UST Faculty Union Vs Bitonio - Self OrganizationDocument1 pageUST Faculty Union Vs Bitonio - Self OrganizationCarl MontemayorNo ratings yet

- People Vs Sandiganbayan CrimproDocument1 pagePeople Vs Sandiganbayan CrimproCarl MontemayorNo ratings yet

- Rodelas Vs Aranza - Evid PhotostaticDocument2 pagesRodelas Vs Aranza - Evid PhotostaticCarl MontemayorNo ratings yet

- NAWASA Vs Secretary - AppealDocument2 pagesNAWASA Vs Secretary - AppealCarl MontemayorNo ratings yet

- Airline Pilots Vs CIR - LABORDocument2 pagesAirline Pilots Vs CIR - LABORCarl Montemayor100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

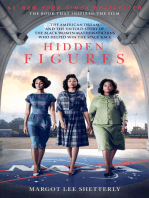

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Compulsory ArbitrationDocument16 pagesCompulsory ArbitrationSamrat ThakkerNo ratings yet

- History of Legal Profession in IndiaDocument13 pagesHistory of Legal Profession in Indiatushar100% (1)

- United States v. Robert Croner, 4th Cir. (2012)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Robert Croner, 4th Cir. (2012)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- CH 3-Consideration and ObjectDocument37 pagesCH 3-Consideration and ObjectInciaNo ratings yet

- Calingin v. CADocument4 pagesCalingin v. CADean BenNo ratings yet

- Sri Lanka Campaing For Ensuring Equal Rights For Muslim Women Gets Broader SupportDocument11 pagesSri Lanka Campaing For Ensuring Equal Rights For Muslim Women Gets Broader SupportThavam RatnaNo ratings yet

- LSPE Terms and ApplyDocument3 pagesLSPE Terms and ApplyMoDsPlayzNo ratings yet

- Advance Paper Corporation V Arma TradersDocument3 pagesAdvance Paper Corporation V Arma Tradersalsawebsitedirector100% (1)

- GoJo Industries v. Dr. FreshDocument4 pagesGoJo Industries v. Dr. FreshPriorSmartNo ratings yet

- Datatreasury Corporation v. Wells Fargo & Company Et Al - Document No. 455Document4 pagesDatatreasury Corporation v. Wells Fargo & Company Et Al - Document No. 455Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Excise Policy Go 164Document21 pagesExcise Policy Go 164Sri KanthNo ratings yet

- Meetings and Proceedings (Companies Act)Document11 pagesMeetings and Proceedings (Companies Act)FlipFlop SantaNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of Caveat EmptorDocument3 pagesDoctrine of Caveat EmptorjaypariharNo ratings yet

- 8 - Yao Kee V Sy-Gonzales - Arts. 11 and 12Document2 pages8 - Yao Kee V Sy-Gonzales - Arts. 11 and 12Nelda EnriquezNo ratings yet

- Kapple V OPM Initial DecisionDocument15 pagesKapple V OPM Initial DecisionKen WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Indian Evidence Act 1872 NotesDocument3 pagesIndian Evidence Act 1872 NotesKunwarbir Singh lohatNo ratings yet

- Logic For Legal ReasoningDocument28 pagesLogic For Legal ReasoningOjing De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Forensic Accounting Tracing Stolen AssetsDocument124 pagesForensic Accounting Tracing Stolen Assetsdavidchey4617100% (3)

- Mendoza v. CFI, G.R. No. L-35612-14, June 27, 1973 (Read Also The Concurrence of J. Barredo)Document5 pagesMendoza v. CFI, G.R. No. L-35612-14, June 27, 1973 (Read Also The Concurrence of J. Barredo)Ryuzaki HidekiNo ratings yet

- A Lifetime and Four DaysDocument3 pagesA Lifetime and Four DaysMaalab Delos ReyesNo ratings yet

- Employment Agreement: (The 'Employer')Document4 pagesEmployment Agreement: (The 'Employer')AJ SalazarNo ratings yet

- Editorial: Judges, Advocates, Police - Learn Honesty: Editor: Nagaraja.M.RDocument16 pagesEditorial: Judges, Advocates, Police - Learn Honesty: Editor: Nagaraja.M.RNagaraj Mysore RaghupathiNo ratings yet

- Human Rights AssignmentDocument13 pagesHuman Rights AssignmentTaiyabaNo ratings yet

- Business Law Today: Standard Edition Text & Summarized Cases, 11EDocument31 pagesBusiness Law Today: Standard Edition Text & Summarized Cases, 11ERaphael AtiyehNo ratings yet

- (Partnership) MIDTERMS Case MatrixDocument22 pages(Partnership) MIDTERMS Case MatrixAbigayle RecioNo ratings yet

- Randazza Response To BoardDocument14 pagesRandazza Response To BoardhuffpostjonxNo ratings yet

- Ronquillo Vs CezarDocument2 pagesRonquillo Vs Cezarsuigeneris280% (1)

- International Law PDFDocument328 pagesInternational Law PDFRupal Yadav100% (2)

- Wanyela - Diplomatic Privileges and Immunities - A Critical Analysis of The Vienna Convention On Diplomatic Relations (1961)Document106 pagesWanyela - Diplomatic Privileges and Immunities - A Critical Analysis of The Vienna Convention On Diplomatic Relations (1961)Moajjem HossainNo ratings yet

- W4 Response LetterDocument2 pagesW4 Response LetterSovereignSonNo ratings yet