Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Summers Star Trek Essay

Uploaded by

scribbyscribCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Summers Star Trek Essay

Uploaded by

scribbyscribCopyright:

Available Formats

MSMI 7:1 Spring 13

doi:10.3828/msmi.2013.2

Star trek and the

Musical depiction of the

alien other

tIM SuMMerS

Musical Depiction of the Alien Other

The multimedia franchise is an increasingly signifcant part of modern

media culture. This article is a case study in reading franchise music.

Star Trek spans forty-eight years and consists primarily of six television

series and twelve flms. These media texts share audiences, fctions and

even musical material. This rich site of musical investigation is explored

through considering the way in which music depicts alien Others.

First, to illustrate the varied, multifaceted, multi-authored space of

television series music, the franchises musical processes are considered

by examining contrasting strategies of the musical depictions of aliens

within the same series. Second, to explore the franchises musical space

over a broader span of time and variety of media, the evolution of

the music for one particular alien species over both flm and television

is traced from the 1960s to the early 2000s.

Star Trek uses music to articulate alterity in a variety of ways.

In some episodes/flms, difering degrees of alterity are musically

expressed, while in others, alien identities are created either through

generic musical signifers of the exoticised Other or through reference

to particular real-world identities (introducing an allegorical dimension

to the depiction). Composed source music also contributes to the

representation of an alien species. Musical depictions evolve as the

same aliens reoccur throughout the franchise with diferent narrative

roles to play, while the diferent media bring their own practices and

contexts to bear upon the musical depictions. The textually-grounded

musical analysis in this article demonstrates how franchise music can

be read.

In flm musicology, enquiry has traditionally focused on either single flms,

individual producers, directors or composers, or it has often been limited to

particular flm genres.

1

Of increasing signifcance in the cultural landscape,

1

The research here

presented was conducted

under the supervision of

Guido Heldt at Bristol

University, who provided

invaluable advice and

insight concerning the

topics discussed in this

article.

20

Tim Summers Musical Depiction of the Alien Other

7:1 Spring 13 MSMI

however, is the multimedia franchise. This article investigates music in

perhaps the prime example of such a franchise fction, one that extends

over both flm and television, and includes multiple composers, musical

strategies and discourses. Star Treks canonic media span forty-eight years,

consist of six television series and twelve flms,

2

and provide a rich site

for musical investigation. In order to successfully navigate this vast musical

landscape (whose very size is part of its appeal), a prominent feature of

the terrain must be selected for focus. Such a topic should be widespread

enough to allow exploration over diferent parts of the territory that

is, diferent franchise incarnations but must be sufciently specifc to

function as a coherent topic of investigation. Here, this exploration takes

the form of examining the way music depicts alien Others.

Science fctions (often allegorical) engagement with concerns such as

alterity and politics provides the potential for rewarding hermeneutic

investigation. The Star Trek universe features sustained encounters with

aliens of various types and narrative functions. This franchise also allows

for the consideration of how diferent composers have engaged with

particular types of alterity and the opportunity to trace the musical

depictions over the range of its media universe.

3

While television music is a growing area of academic interest,

4

the topic

has been isolated from flm music: Star Trek, however, both in general,

and in its music, permeates cross-media boundaries. In this context, flm

and television cannot be considered as entirely separate entities, since they

share audiences, fctions and even musical material. Franchises like Star

Trek allow for a more integrated discussion of screen media music that

does not segregate music for diferent media types: music across media

forms can be connected, compared and contrasted. Star Treks music,

and specifcally its articulation of alterity, is shaped by the constraints

and opportunities provided by the musical context of any one medium.

To explore music in the Star Trek universe, two aspects will be

investigated. First, to illustrate the varied, multifaceted, multi-authored

space of television series music, the franchises musical processes are

considered by examining contrasting strategies of the musical depictions of

aliens within the same series. Second, to explore the franchises musical

space over a broader span of time and variety of media, the evolution

of the music for one particular alien species over both flm and television

is traced from the 1960s to the early 2000s.

Star Trek uses music to articulate alterity in a variety of ways. In some

episodes/flms, difering degrees of alterity are musically expressed, while in

others, alien identities are created either through generic musical signifers

of the exoticised Other or through reference to particular real-world

identities (introducing an allegorical dimension to the depiction). Composed

2

The series are Star Trek

(1965 pilot, 19661969);

Star Trek: The Animated Series

(19731974); Star Trek: The

Next Generation (19871994);

Star Trek: Deep Space Nine

(19931999); Star Trek:

Voyager (19952001); and

Enterprise (20012005).

Eleven flms have had

theatrical releases, with the

twelfth currently awaiting

release. The flms and

television episodes form

the franchise canon

the works that ofcially

contribute to the fctional

universe, as distinct from

works of fan fction or

satellite texts that are

considered apocryphal.

Following the tradition of

Star Trek discourse, episode

names are contained in

inverted commas. Time

codes are from DVD

Region 2 releases and

musical examples are

transcriptions by the author

unless otherwise indicated.

3

This article follows on

from Robynn Stilwells

research on the X-Files

(2003), though the

specifcity and often agenda-

laden nature of Star Treks

Othering, along with the

size of the franchise space

make the substance of this

discussion a complementary

contrast to Stilwells

work. Jeremy Barham

has discussed the use of

Mahler in the episodes

Counterpoint (Voyager

1998) and has briefy

mentioned the alien music

heard in Virtuoso (Voyager

2000) as part of a discussion

on romanticism and utopia

in science fction screen

music (2008: 25560).

4

See, for example, Rodman

2010 and Deaville (ed.) 2011.

21

Tim Summers Musical Depiction of the Alien Other

MSMI 7:1 Spring 13

source music also contributes to the representation of an alien species.

Musical depictions of particular alien species can be seen to evolve as

the same aliens reoccur throughout the franchise with diferent narrative

roles to play and as the diferent media bring their own practices and

contexts to bear upon musical depiction.

Star Trek: The Original Series (TOS)

This investigation of the franchises music begins with the frst incarnation

of Star Trek the 1960s television series. A variety of musical representations

of aliens, and of strategies for such depictions, may be found within the

same franchise area, created and deployed by more than one composer.

It is important to recognise the multi-authored space that the music of

a franchise, even a single series or episode, may represent.

Of the original eighty episodes of Star Trek, only thrity-nine had music

written for those specifc episodes. As was typical for 1960s television,

episodes were scored in one of three ways, as composer Fred Steiner

relates (1983):

In a full score, the composer would write music for an episode

in a manner similar to scoring a movie.

In a tracked score, the music editor would create a score made

from cues or excerpts of cues originating either from music written

for particular previous episodes or music specifcally written by the

series composers as Star Trek library cues to suit generic situations.

In a composite score, newly written music would be supplemented

with either library cues or cues written for previous episodes.

So extensive was the reuse of cues that the audience learnt the signifers

of particular pieces. Additionally, composers would adopt and develop each

others themes and stylistically imitate one another in order to create a

homogenous musical soundworld for the series as a whole.

5

As well as the usual limitations of televisions budget and time, composers

were challenged to bring music to bear for the creation of the strange

new worlds, new life and new civilizations (as the opening voiceover

puts it) that the show sought to depict, but which was constrained by

the limited special efects available to 1960s television productions.

A Spectrum of Alterity

Perhaps the most informative example for revealing the musical strategies

utilised by Star Trek in depicting alien alterity is one in which a spectrum

5

For example, a theme

from Alexander Courages

The Man Trap (TOS

1966) score was used by

Fred Steiner in Charlie

X (TOS 1966) (Bond

1999: 17), while Gerald

Frieds Spock themes

were developed by other

composers, see fn. 11.

22

Tim Summers Musical Depiction of the Alien Other

7:1 Spring 13 MSMI

of alienness is created. The Cage, Star Treks 1965 pilot episode, centres

on the imprisonment of the starship Enterprises human Captain Pike

( Jefrey Hunter) by telepathically advanced aliens (Talosians) who, after an

Earth ship crashes on their planet, decide to cultivate a slave population

of humans to regenerate their planet. The Talosians plant illusions into

Pikes consciousness to coerce him (beginning initially with the fabrication

of human survivors from the crash). Pikes intended mate, Vina (Susan

Oliver), is in reality the sole survivor from the Earth ship and while

human, has had her appearance altered by the Talosians, and works to

assist them.

Music delineates diferent levels of alterity in the episode, both of

species and environment. These levels are, in order of increasing alterity:

the Enterprise/Captain Pike; the surface of the planet Talos; the human/

alien hybrid Vina; and the Talosian aliens, who, in stereotypical fashion,

are mind-controlling aliens. The diferentiation/association between levels

of alienness is articulated principally by musical timbre, orchestration

and motivic material.

In this full score, comprising entirely newly written music, Alexander

Courage scores the Enterprise and Pike with melodic material from the

Star Trek title fanfare (Figure 1), most often on horns, with slow moving

pedal tones in the low woodwinds (bass clarinet, contrabass clarinet). The

harmony is directional, foregrounding its contrapuntal construction; the

careful voice-leading provides a sense of stately control in the harmonic

intersections of the instrumental parts. A prime example of this scoring

is the Doctor Bartender cue (Figure 2) [05:24], which accompanies

Pikes confession to the doctor that he is tired of the strain of command.

Musically and dramatically, this scene reveals to the audience Pikes

private emotions: it serves to establish a humanness against which the

alien will later be contrasted. The cue features an oboe and clarinet duet

over a warm sonorous texture from low woodwinds and closely spaced

horns. These mellow sonorities, using seventh and ninth harmonies, are

associated with the Enterprise crew and are starkly diferent to the sonic

representation of the planet surface.

Figure 1: The horn fanfare from Star Treks main title theme.

(From composers sketch reproduced in Steiner 1985: 296.)

23

Tim Summers Musical Depiction of the Alien Other

MSMI 7:1 Spring 13

Figure 2: Doctor Bartender cue opening: a slow, truncated variation on the

main title fanfare.

To characterise the planet surface, the episode uses an ingenious aural

trick. Scenes set on the surface are accompanied by a constant sound

efect which is produced by the local blue plant life. This sound is at

once static and in constant fux, featuring overlapping multiple glissandi

arches at diferent pitches and tempi, sounding similar to the micropoly-

phonic opening of Ligetis Atmospheres (1961).

6

The episode is at pains to

explain the source of the sound: Spock and Pike isolate elements of the

sound by stopping the vibration of individual plant leaves [11:59], thus

dissipating the mystery of the sound in favour of the logically alien

(Figure 3). The science fction genre of the series is here emphasised:

an ominous sound efect such as one might fnd in a horror flm is

explained as a natural part of an alien world.

Using musical instruments/musical sounds for diegetic sound efects

(such as the sound of the plant or the chimes that accompany the Talosians

automatic doors), creates a shared, instrumented musical middle ground

between score and sound efect, which ties the

scores descriptive power closer to the visual text.

Musical elements are tightly integrated into the

depiction of environment. Binding music closely

to the visual allows the narrative and descriptive

component of the non-diegetic musical sound

to be more explicitly interpreted by the viewer.

The character Vinas initial appearance

is accompanied by music that marks her as

diferent from the (illusionary) crash survivors

[13:16], who share melodic material and instru-

mental timbres with the Pike/Enterprise cues.

At this point in the episode, the script does not

betray Vina as alien, yet the score ostentatiously

indicates her diference to the audience. While

the music signifes diference it does not initially

indicate what this diference is: it may be her

6

The use of Ligetis piece

in Kubricks 2001: A Space

Odysseys would occur four

years later. Appropriately,

Alex Ross has described

Atmospheres as a seductive

threshold to an alien

world (2007: 467).

Figure 3: The musical fora of the planet Talos.

The plant vibrates, producing the sound

efect. When individual leaves are dampened,

elements of the soundscape stop.

24

Tim Summers Musical Depiction of the Alien Other

7:1 Spring 13 MSMI

femaleness in contrast to the men who surround her or something more

secretive in the narrative.

7

Figure 4: Vinas theme.

Vinas motif (Figure 4) immediately contrasts with the human-associated

material. It is accompanied by scattered percussion, foregrounding the

uncertainty surrounding the character through pointillistic textures. The

chromaticism contrasts with the heroic, assertive material for Pike. While

the harmonic context is secure, the swooping portamento fgures are

performed rubato, the uncertainty of their progress implying improvi-

sation. This music treads a fne line between instability and ambiguity

as an illustration of her persona. Such obvious musical signifcation is

typical of the clearly descriptive and narrative function of music in

the series.

Vinas theme is later repeated as a countermelody to the Talosians

material (Figure 5), hinting at collusion between the two [13:53]. Yet,

the low futes that often carry Vinas motif are close to the pastoral

soundworld of the Enterprise/Pike material the score demonstrates her

hybridity, held between two worlds. When her theme is repeated and

extended, a wordless soprano, as heard in the Star Trek main title theme,

joins the melody as Vina, siren-like, lures Pike into captivity.

8

Figure 5: The Talosians theme.

Compared with Vinas motif, the Talosians material is more metrically

regular, implying the imposition of mechanisation; the chromatic lower

part determinedly descends with little regard for contextual harmonic

constraints [13:36]. The harmonic underpinning of this passage is wayward

the pitch-by-pitch unfolding continually betrays any consistent harmonic

7

Susan McClary

has discussed how

chromaticism has often

been employed as part

of the depiction of exotic

female sexual excess (1991:

esp. Chapters 3 and 4).

Such use of chromaticism

has been taken up as

part of the Classical

Hollywood scoring

lexicon (Kalinak 1992:

12021).

8

The resulting timbre is

similar to the theremin,

a staple of science fction

music. The use of the

textless (especially female)

voice as a realisation

of the supernatural has

precedent in art music,

such as in Lyra Celtica by

John Foulds; Debussys

sirens in Nocturnes;

Neptune in Holsts Planets;

the chorus of Ravels

Daphnis et Chlo; or Kaitos

accompanying chorus in

dIndys Fervaal.

25

Tim Summers Musical Depiction of the Alien Other

MSMI 7:1 Spring 13

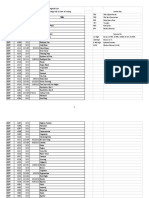

P

i

k

e

/

E

n

t

e

r

p

r

i

s

e

V

i

n

a

T

a

l

o

s

i

a

n

s

T

r

e

n

d

I

n

c

r

e

a

s

i

n

g

a

l

t

e

r

i

t

y

R

h

y

t

h

m

R

e

g

u

l

a

r

m

e

t

r

i

c

p

h

r

a

s

e

s

,

b

u

t

w

i

t

h

e

x

p

r

e

s

s

i

v

e

r

u

b

a

t

o

I

r

r

e

g

u

l

a

r

/

u

n

c

e

r

t

a

i

n

/

g

e

s

t

u

r

a

l

;

m

o

t

i

f

r

e

p

e

a

t

e

d

,

s

o

r

h

y

t

h

m

b

e

c

o

m

e

s

p

r

e

d

i

c

t

a

b

l

e

V

e

r

y

r

e

g

u

l

a

r

,

p

o

s

s

i

b

l

y

m

e

c

h

a

n

i

z

e

d

T

r

e

n

d

R

e

m

o

v

a

l

o

f

h

u

m

a

n

e

x

p

r

e

s

s

i

v

i

t

y

o

f

r

u

b

a

t

o

H

a

r

m

o

n

y

9

t

h

c

h

o

r

d

s

f

r

o

m

t

i

t

l

e

.

S

o

m

e

c

o

m

p

l

e

x

c

h

o

r

d

s

w

i

t

h

a

d

d

e

d

2

n

d

s

/

7

t

h

s

/

9

t

h

s

(

n

o

t

h

a

r

s

h

l

y

d

i

s

s

o

n

a

n

t

)

,

c

l

e

a

r

a

n

d

d

i

r

e

c

t

i

o

n

a

l

H

a

r

m

o

n

i

c

f

r

a

m

i

n

g

p

r

o

v

i

d

e

d

l

i

k

e

i

m

p

r

o

v

i

s

a

t

i

o

n

U

n

c

e

r

t

a

i

n

h

a

r

m

o

n

i

c

g

r

o

u

n

d

p

i

t

c

h

-

t

o

-

p

i

t

c

h

a

t

t

e

m

p

t

s

t

o

n

d

t

o

n

a

l

g

e

o

g

r

a

p

h

y

T

r

e

n

d

L

a

c

k

o

f

s

e

n

s

e

o

f

h

a

r

m

o

n

i

c

g

e

o

g

r

a

p

h

y

/

f

u

n

c

t

i

o

n

/

d

i

r

e

c

t

i

o

n

;

i

n

c

r

e

a

s

i

n

g

l

y

,

t

h

e

t

o

n

i

c

a

p

p

e

a

r

s

m

o

b

i

l

e

M

e

l

o

d

i

c

C

o

n

t

o

u

r

S

t

r

i

d

e

n

t

,

h

e

r

o

i

c

,

c

l

e

a

r

d

i

r

e

c

t

i

o

n

a

l

c

o

n

t

o

u

r

C

h

r

o

m

a

t

i

c

,

b

u

t

f

r

a

m

e

d

b

y

h

a

r

m

o

n

y

f

o

r

s

t

a

b

i

l

i

t

y

U

n

c

e

r

t

a

i

n

m

e

l

o

d

i

c

d

i

r

e

c

t

i

o

n

i

r

r

e

g

u

l

a

r

r

e

p

e

a

t

o

f

m

e

l

o

d

i

c

m

a

t

e

r

i

a

l

.

T

r

e

n

d

D

e

c

r

e

a

s

i

n

g

c

l

a

r

i

t

y

o

f

m

e

l

o

d

i

c

s

t

r

u

c

t

u

r

e

a

n

d

s

e

n

s

e

o

f

p

e

r

i

o

d

s

/

p

h

r

a

s

i

n

g

T

i

m

b

r

e

M

e

l

l

o

w

t

e

x

t

u

r

e

s

e

m

p

h

a

s

i

z

e

d

:

c

l

a

r

i

n

e

t

s

,

h

o

r

n

s

,

u

t

e

,

h

i

g

h

o

b

o

e

S

o

p

r

a

n

o

,

d

o

u

b

l

e

d

u

t

e

s

,

s

o

m

e

e

l

e

c

t

r

o

n

i

c

i

m

p

o

r

t

,

g

u

i

t

a

r

E

l

e

c

t

r

o

n

i

c

s

,

u

n

k

n

o

w

n

s

o

u

n

d

s

H

e

c

k

e

l

p

h

o

n

e

(

u

n

u

s

u

a

l

i

n

s

t

r

u

m

e

n

t

,

b

u

t

s

o

m

e

r

e

l

a

t

i

o

n

t

o

k

n

o

w

n

t

i

m

b

r

e

o

f

t

h

e

o

b

o

e

)

T

r

e

n

d

I

n

c

r

e

a

s

i

n

g

m

e

t

a

l

l

i

c

t

i

m

b

r

e

s

a

n

d

e

l

e

c

t

r

o

n

i

c

i

n

s

t

r

u

m

e

n

t

s

.

F

a

m

i

l

i

a

r

i

t

y

o

f

k

n

o

w

n

i

n

s

t

r

u

m

e

n

t

s

f

a

d

e

s

T

a

b

l

e

1

:

E

x

p

r

e

s

s

i

o

n

s

o

f

a

l

t

e

r

i

t

y

a

n

d

m

u

s

i

c

a

l

t

r

e

n

d

s

.

26

Tim Summers Musical Depiction of the Alien Other

7:1 Spring 13 MSMI

context for the listener. Further attempts to comprehend the passages

musical organisation are hampered by the slow tempo (which challenges

a sense of melodic direction), chromaticism and the irregular repetition

pattern. The harmonic dislocation gives a sense of obtuse logicality: there

is a logical process at work in the chromatic lower line, but the unceasing

descent marks its alienness. In terms of timbre, the motif is more alien

than Vinas motif, thus very alien in comparison to the Pike/Enterprise

material. By using echoplexed guitar and the Heckelphone,

9

a more alien

timbre is created as the familiar guitar and oboe here appear mutated:

the former by sonic manipulation, the latter by the Heckelphone timbre.

The increasing electronic element, in the form of the bass guitar and

electric organ, is subtle but nevertheless afecting. From these levels of

musically diferentiated alterity, it is possible to construct a spectrum of

how musical elements articulate the alienness of characters in the episode

(see Table 1).

From Alterity to Orientalism

In one sequence in The Cage, the musical depiction of alterity develops

beyond denoting measured Otherness into a fully-fedged Orientalist

caricature. The Talosians telepathically generate scenarios designed to

encourage Pike and Vina to mate. In one such illusion, Vina appears

as an alien slave, in an obvious reference to the clichd Orientalist

image of a harem [43:18] (Figure 6). Vina, accompanied by musicians,

dances increasingly provocatively until Pike, overcome, fees the room.

This sequence resonates with Strausss Salome (1905) and in a similar

way to the opera, music which has already

capitalised on exoticism, does so to an even

greater degree, to the extent of achieving a

near-parodic tone. A variation on Vinas theme

is used for the sequence (Figure 7), heard in the

double reeds, accompanied by gong strikes and

bells. An accompanying electric guitar relates

Vina to the Talosians, under whose control she

remains. The ubiquitous use of parallel fourths

is vulgar and extreme. As the dance progresses,

octave doubling is added, with more closely

repeated fragments and powerful percussion,

until the intensity overwhelms Pike. Just as the

already-alien Vinas skin tone has turned green,

so the music has become exotic within a frame

of exoticism.

9

The Heckelphone is a

double reed instrument,

similar to a bass oboe, but

with a large globular bell

and a wide conical bore

(Bate and Finkelman

2013).

Figure 6: Vina, transformed into an Orion

slave girl, performing her seductive dance.

27

Tim Summers Musical Depiction of the Alien Other

MSMI 7:1 Spring 13

Figure 7: Vinas motif exoticised into the dance music.

If, like the rest of the illusion, the music (to which the image gives

some concession of diegetic sourcing) is created by the Talosians, this could

be read as another expression of their alienness: music that is supposed

to attract Pike to Vina produces the opposite result, demonstrating the

lack of understanding of the efect of music on the human by the aliens.

Ironically, the aliens themselves have manufactured exoticist music.

The spectrum of musical alterity in The Cage is used to articulate

the relative alienness of characters in the episode. Television demands

immediate and clearly communicative musical signifcation, as The Cage

exemplifes. Music from The Cage became part of the series music

library, but when the cues were subsequently reused out of their original

narrative context, this overall spectrum of alterity was dissolved. The

music was mixed and matched with other cues from other composers

and was heard in new episode contexts, to accompany a wide variety of

alien characters. In this reuse, the music for aliens in The Cage thus

came to stand as a signifer of alienness itself.

Alien Identities and Hybridity

The Cage sets up a spectrum of musical alterity, anchored by a defnition

of the human and based upon musical features concerning timbre,

harmony, melodic contour and rhythmic regularity. The treatment of

aliens in the score of The Cage is relatively simple, but more complex

issues concerning hybridity and species identity (read in allegorical terms

as racial identity) are musically evident in other episodes.

10

One such

episode is Amok Time (1967).

This episode from Series 2 centres on the Enterprises Mr Spock

(Leonard Nimoy), who is half-Human and half-Vulcan. The Vulcan

way of life is one of total logic suppressing emotions and acting

with dispassionate rationality. Elements of the Vulcans ancient culture,

which was extremely emotional and violent, still survive in the traditional

rituals. Vulcans experience an intense mating season which makes them

emotionally unstable. In the episode, Spock begins to lose control of

10

Nichelle Nichols,

who portrayed Star

Treks African-American

communications ofcer,

reads the character

of Spock as being an

allegory of children with

mixed racial heritage

(1994: 138). An explicit

articulation of this issue

would not have survived

the censor, though science

fctions apparent chrono-

logical distance allows the

treatment of such topics

through allusion.

28

Tim Summers Musical Depiction of the Alien Other

7:1 Spring 13 MSMI

his emotions as a result of this mating period and returns to planet

Vulcan. On arriving, his betrothed wife (TPring, played by Arlene

Martel) manipulates ritual law to force Captain Kirk (William Shatner)

and Spock to fght to the death so she is free to marry the man she

really loves (another Vulcan). Kirk fakes death, Spock is ritually free and

both return to the Enterprise.

Amok Time uses similar criteria of musical alterity to those identifed

in The Cage. In the case of a television series, as viewers return week

after week to hear musical alterity expressed in a particular way, audience

members learn to recognise and interpret music by these same musical

criteria of alienness. This facilitates a more complex musical signifcation of

alterity as viewers become attuned to this dimension of a musical identity.

Spocks status as half-human and half-Vulcan is matched by the two

distinctive musical subjects with which he is accompanied (Figures 8

and 9).

11

Figure 8: Spocks theme A.Bass guitar [3:58].

Figure 9: Spocks theme B.Bass guitar [4:58].

12

The A theme is heard when Spock is seen to be violent or irrational.

The intervals are irregular and angular: tritones and gestures that extend

over the range of major sevenths furnish the motif with a kind of

uncontrolled lashing out gesture that correlates directly with Spocks

emotional and physical state.

The latter, predominant motif (B), which serves as Spocks main theme,

is heard when Spock is being more openly emotional, honest, calm or

shown in a more sympathetic manner. The episodes composer, Gerald

Fried, described his construction of motif B as follows:

[Spock] struggled to express emotion, so I picked an instrument where

emotion is a struggle to express, like the bass guitar. So I wrote a

lyrical theme but played it with a plunky instrument, which I felt

somehow might match Spocks inability to be emotionally accessible.

(interviewed in Bond 1999: 78)

11

Theme B became a

recurring motif for Spock,

used in both tracked and

newly written scores:

Is There in Truth No

Beauty? [frequent use,

4:50 etc.] (1968, score

by George Duning, not

tracked); The Paradise

Syndrome [26:08]

(1968, score by Fried,

not tracked), A Private

Little War [16:36] (1968,

tracked), Journey to

Babel [2:03+] (1967,

tracked). Season 3s

library included library

versions of Spock-related

music from Amok Time

(Bond 1999: 545).

12

Steiner (1985: 302)

reproduces a score excerpt

from later in the episode

[13:36] which notates the

theme diferently. Due

to the practicalities of

playing this motif on the

bass guitar, the above

fgure is a more accurate

representation of the

theme as heard.

29

Tim Summers Musical Depiction of the Alien Other

MSMI 7:1 Spring 13

Spocks B motif is often accompanied by an ostinato in high reed

instruments (Figure 10), which contrasts heavily with the timbre, range

and style of Spocks B melody. This has the efect of emphasising, through

contrast, what Fried refers to as the lyrical properties of the B motif.

Figure 10: Ostinato accompaniment to Spocks theme B: oboe and fute

[4:51].

While both of Spocks themes are harmonically transient and gestural,

comparing reductive outlines of the melodies reveals how they attempt to

portray an erratic and a stable Spock respectively (Figures 11 and 12).

Figure 11: Spocks theme A reduction.

Figure 12: Spocks theme B reduction.

Interpreted under the same concepts of musical alienness that were

made explicit in The Cage, Spocks A theme is more alien, while the

B theme is comparatively human. In this way, the A motif is seen to

speak for, and denote, his alien properties, while B does the same for

the human component of his hybrid status.

The motifs are deployed to align certain actions and emotional states

of the character with the human, while others are associated with

the alien. At emotional moments, such as following Kirks death and

during the nurses expression of her unrequited love for Spock, Spocks

B theme is heard in timbres such as a high-register cello. This gives

the impression of yearning as the cellos timbre strains for the highest

notes, human-ising his motif from the picked electric bass timbre to

the bowed cello. As well as scoring (and identifying) the emotions that

Spock attempts to express, the B motif simultaneously signifes that in

doing so, Spock is striving to become more human through integrating

emotional expression into his personality and behaviour. When Spock

is violent, emotionally unstable and erratic, the A motif sounds in the

electric guitar, denoting these actions as alien. Spocks hybridity is thus,

through music, used as a site to defne the human, redefning human

30

Tim Summers Musical Depiction of the Alien Other

7:1 Spring 13 MSMI

only through what are perceived as the positive aspects of the species,

shifting the undesirable (though, in truth, equally human) properties

onto the alien Other.

Throughout the franchise, Star Trek discusses what it means to be

human, mostly by using non-human characters such as Spock or the

robot Data (Brent Spiner in Star Trek: The Next Generation) and claiming

their humanness, based not upon biological essentialism, but upon a

set of qualities and attributes that comprise the human. Through this

process, the human and humanity are (re)defned as the most highly

valued qualities of the species:

Star Trek defnes humanity not by static primordial essences but by a

dynamic question for self-transcendence. It is the act of seeking and

questioning, the assertion of freedom, the free expression of compassion

and sacrifcial love, and the refusal to be bound by biology or chauvinism

or custom or worship or fear or hate or compulsion that defnes the

human.

(Wagner and Lundeen 1998: 61, emphasis in original)

The dual Spock themes illustrate how Star Treks overall agenda concerning

the defnition of the human is similarly enacted through the musical score.

Intertextuality and Orientalism

Alien identities in Star Trek are also created through musical intertexual

allusion, as is the case with TPring (Spocks betrothed wife) in Amok

Time. TPring is presented as a scheming mastermind, prepared to

sacrifce Spock and/or Kirk for her own gain. It is appropriate, then,

given the similarity of characters, that her motif imitates Salomes dance

from Strausss opera of the same name, complete with tambourine

accompaniment (Figures 13 and 14).

Figure 13: TPrings theme.

Intertextual links are a common way of musicalising the alien (and this is

discussed further below), though in TPrings case, the citation additionally

admits typical Orientalist musical techniques. Musical Orientalism is also

found in the depiction of Vulcan society.

31

Tim Summers Musical Depiction of the Alien Other

MSMI 7:1 Spring 13

Vulcan culture is depicted using traditional Orientalist signifers. The

Vulcans were clearly constructed from Orientalist stereotypes, outftted

with mysterious mental powers and mystical philosophies and rituals,

encased in stylised Orientalia (Dariotis 2008: 66). Vulcan society is

dominated by gongs and bells, both in Amok Time and Star Trek III

(1984). Such iconography is part of the depiction of the Vulcans as a

historical and Oriental Other.

The ritual fght between Kirk and Spock is accompanied by a musical

cue which is bombastic and presented at a high volume in the sound

mix (Figure 15). Frieds own words concerning the composition of this

cue underline the choice of a primitivist style, [The Vulcans] went back

to their primal roots, so that made it easy; I was able to write a kind

of ethnic aboriginal ceremony. (Fried interviewed in Bond 1999: 78.)

The fght cue draws on typical Orientalist and Primitivist musical

styles to present the cultural activity as alien, but it is simultaneously

shaped by the demands of television music. The cue echoes Stravinskys

Sacre du Printemps and Khachaturians Sabre Dance the former trading

heavily in primitivism, the latter in Orientalism. In using such obvious

signifers of alterity, even the alien parts of Spocks identity are shown

to be less Other than the Vulcan culture.

Frieds ferocious tutti homophony moves in parallel motion, split into

two separate harmonic layers (Figure 16). Fried makes these layers exactly

alike, displaced by a semitone and moving in semitone motion. Four chords

are used, covering eleven pitch classes. The movement maintains a sense

of direction, period and arrival, although through its chromatic stasis,

it does not function as a harmonic progression in any emphatic sense.

The passage is heard as a single melody, multiply harmonised; thus,

resolution is in melodic conclusion not tonal resolution. Along with

the modular phrase assembly of the cue, this harmonic construction is

linked to the demands of television. Composers needed to write so as

Figure 14: Salomes Dance, authors reduction, bb. 338.

32

Tim Summers Musical Depiction of the Alien Other

7:1 Spring 13 MSMI

to allow for the easy re-editing and reuse of cues in future episodes.

A harmonic resolution would require a progression and presumably be

synchronised with an on-screen dramatic conclusion or development.

Such structural defnites would hinder its use in tracking (which typically

involved extracting and repeating fragments of cues). Here, resolution

of melodic period does not require harmonic resolution. Fried writes a

long, fercely dissonant cue in a way to be palatable for a TV audience:

the interspersed monophonic passages provide harmonic relief and a

tonal anchor, while emphasising a melodically-privileged listening strategy.

Frieds orchestration employs rising tonic-dominant fgures in the horns,

which imports a ritualistic/rustic element to the cue. These fgures are

closely recorded, giving the impression of the pitches sonically lurching

Figure 15: Ancient Battle cue, transcribed and reduced from composers

sketch in Bond 1999: 21.

Figure 16: Reduction of Figure 15, b. 4.

33

Tim Summers Musical Depiction of the Alien Other

MSMI 7:1 Spring 13

towards the listener, resonating with the fghting motions on-screen. This

is a cue that attempts to captivate and engage the viewer/listener (a

task far more crucial to television than cinema, which takes place in a

distraction-free environment) in providing an exaggerated aural spectacle

to amplify the rather limited visual component of the action.

The discussion of musical alterity in the original series of Star Trek has

considered only one site of the franchise, but nevertheless illustrates the

variety of processes and strategies found within this domain. The Cage

reveals the musical foundations upon which notions of alienness and

humanness in this music rest, and it uses these to create a spectrum

of alterity, while Amok Time deals with hybridity of identity and

involves strategies of musical alien identity that rely on intertextuality

and Orientalism. Amok Time also uses music to advance the ideological

outlook of the series as a whole. Having examined diferent techniques

and methods of alterity within one franchise site (and how these strategies

interact and impact upon one another from episode to episode) it is now

appropriate to consider the musical depiction of a particular alien species

over the chronological span of the entire franchise.

The Klingons

The Klingons form one of Star Treks prized traditions. Music plays an

important part in constructing this fctional species, both through dramatic

score and source cues. Tracing the Klingons musical depiction through

the franchise illustrates the shifts in development of their identity as it

evolves between and across media.

The Original Series (19661969)

In the frst Star Trek series, the Klingons serve as recurring villains, with

a clear contemporary political allegory. The Klingons, positioned as the

Soviets[,] are evil, dark and underhanded. They are a totalitarian and

imperialist regime who deem battle glorious (Bernardi 1998: 5051).

This association resonates with the musical depiction of the Klingons to

greater and lesser extents across the franchise.

Klingons frst appeared in Errand of Mercy (1967), an entirely tracked

episode. No coherent or original musical identity is given to the Klingons,

though they are often accompanied by cues written for aliens in earlier

episodes, such as the Romulan theme from Balance of Terror (1966)

or the robot named Ruk in What Are Little Girls Made Of ? (1966).

Thus the Klingons are musically designated as generically alien from

the signifcation of alterity reproduced in the pre-existing cues. Some cues

34

Tim Summers Musical Depiction of the Alien Other

7:1 Spring 13 MSMI

written for particular aliens (such as the Romulans or Ruk), not only

serve the depiction of the characters for which they were created, but, as

the cues are used repeatedly throughout the series to accompany newly

introduced aliens, come to stand as signifers of the alien more generally.

The frst music specifcally written for the Klingons occurs in Fridays

Child (1967). The Klingons receive a motif (Figure 17), which is fragmen-

tarily prefgured when the word Klingon is mentioned [1:25], and a

Klingon frst seen [2:07]. It is heard in full when a Klingon is confronted

[3:42]. The motif is mostly heard in low-register piano octaves, doubled

with lower strings and later transformed into a tutti rendition for dramatic

climaxes [20:15]. In a brass-heavy version [26:50], it is accompanied by

double-stopped, grinding low string sforzando incisions.

Figure 17: Klingon motif from Fridays Child.

The Klingon motif demonstrates musical alien-ating techniques identifed

above as typical of TOS: harmonic dislocation is created by using all

twelve chromatic pitches, as a tone-row. The angularity of the melody

combines serial hermeticism with visceral gestures enhanced by marcato,

dry timbres. The low register occupies a masculine vocal range and

contributes a less distinct sense of pitch it is more sonically mysterious,

while the percussive element demonstrates the militaristic dimension of

the Klingons identity. The Fridays Child score was used extensively

for tracking, including use in subsequent episodes featuring the Klingons

(such as A Private Little War 1968), transferring the particular musical

alien identity from one episode to another.

The second TOS episode with Klingon-specifc music is Elaan of

Troyius (1968). In this episode, the Klingons are seen infrequently, but

occasionally show themselves to attack the Enterprise. The Klingons are

given a short motif, heard mainly in unison brass (Figure 18).

Figure 18: Klingon motif from Elaan of Troyius.

While the Fridays Child motif is not reprised here, the Elaan of

Troyius material also characterises the Klingons in this series. This

motifs fanfare gestures emphasise the militaristic qualities of the Klingons,

35

Tim Summers Musical Depiction of the Alien Other

MSMI 7:1 Spring 13

while the whole tone harmonic profle lends a distinctly elusive air to

this aggressive and unpredictable theme, perhaps as a depiction of the

elusive Klingons in Elaan of Troyius.

The motif is sounded with, or to imply, the Klingons presence. In

being articulated viscerally in powerful instrumentation, the motif acts as

a potent auditory expression of the Klingons role and presence in the

episode. The music seems anchored to their identity as much as any other

aspect of their diegetic incarnation. The emphasis on brass instruments

prefgures a later Klingon musical association developed in other media.

Star Trek Films

The Motion Picture (TMP) (1979)

Star Trek has not only existed on the small screen. Eleven Star Trek feature

flms have been released into cinemas over thirty years, with a twelfth

awaiting release at the time of writing. Klingons feature in many of these

flms. They appear briefy at the beginning of the frst flm, Star Trek:

The Motion Picture (1979). This flm introduced the revamped Klingon

physiognomy, language and spaceships that were subsequently used

throughout the franchise.

13

To match this overhaul, a new musical identity

was forged in Jerry Goldsmiths score that would be similarly prolifc. The

Klingons are musically introduced while their spaceships are on-screen,

before they are seen in the fesh. The accompaniment material for the

opening cue [00:04:33] is a fundamental element of the musical identity: a

sprightly march, marking each quaver. The strings play open ffths, pizzicato

in upper strings, col legno in lower. Goldsmith subsequently introduces

high-pitched angklungs: tuned Javanese bamboo percussion instruments.

Within moments, a distinctive soundworld is created for the aliens. The

main Klingon melody follows [00:04:48] (Figure 19). Elements of prior

musical depiction can be heard in this newly established theme: the brass

timbres and harmonic motion of this material are reminiscent of Elaan

of Troyius, while the percussive Fridays Child score is also echoed here.

Figure 19: The frst appearance of the Klingon Motif, transcribed with

reference to the descriptions of the composers sketch in Wrobel (2002).

13

While, in TOS, the

Klingon make-up simply

consisted of darkened skin

colour with bushy facial

hair, from TMP onwards,

elaborate latex-moulded

ridged foreheads were

used. For the flm, new

models were created for

the Klingon spaceships

and the aliens were heard

to speak in a non-English

language.

36

Tim Summers Musical Depiction of the Alien Other

7:1 Spring 13 MSMI

However, the Klingons are not the villains in this flm, and serve as

a rustic Other with which the main antagonist of the flm (a mysterious

technological alien) is contrasted. The melodic identity uses ffth intervals

to mark this primitive-ness of the Klingons, as well as invoking a military

signal with heraldic associations to describe the bellicose qualities of the

aliens. The music establishes a distinctive alien identity against which the

technological alien Other is (musically and otherwise) contrasted. In a

flm context more extensive and more unusual instrumental resources

are available for the score and, unlike the scoring strategy for the

television series, no consideration has to be given to the reuse of musical

material in tracking: the Klingon musical identity is distinct, specifc and

memorable, and does not need to prioritise the unspecifcally alien in

order to facilitate easy reprise in future non-Klingon contexts, as might

be required by music written for a television episode.

Star Trek III (1984)

Unlike in TMP (1979), the Klingons, absent from Star Trek II (1982),

serve as the primary antagonists of the third flm (1984). James Horners

Klingon themes do not quote Goldsmith, but feel the infuence of his

material and bear a resemblance to motifs from TOS. First heard at

00:08:38, a pulsing percussion beat (on clackers and a light metallic

tapping, punctuated by anvil-like instruments and boobams, reminiscent of

the Klingon theme accompaniment in TMP) holds a brooding low brass

ostinato (Figure 20) in place. A non-brass horn, probably a rams horn

shofar, enters on a stable pitch only to fall away in a descending glissando.

The shofar is traditionally used in Jewish religious services, implying an

ancient, ritualistic association. In Star Trek V (1989), Goldsmith would in

turn borrow this addition to the musical identity.

Figure 20: Horners Klingon theme ostinato accompaniment.

The main Klingon motif is played in the high brass, frst as an isolated

cell and then expanded into the theme proper (Figures 21 and 22).

Figure 21: Klingon motivic cell [00:09:02].

37

Tim Summers Musical Depiction of the Alien Other

MSMI 7:1 Spring 13

Figure 22: Klingon cell sequenced as theme [00:09:33]. Note how this motif

reprises the augmented-ffth framework (F, C-sharp, F) and whole tone

scale from the Klingon material in Elaan of Troyius.

As in previous depictions, the material emphasises militarism, but

without the strident gestures of Goldsmiths theme. These are not noble

Klingons, but evil villains: the motif is a slippery ornamented single

pitch that does not invoke an heraldic fanfare (as in Goldsmiths material).

The musical signifcation attached to the Klingons is made clear when

Horner reuses this theme for the eponymous creatures in his Aliens (1986)

score, forging an intertextual alien musical identity in the process.

Star Trek V (1989)

When Jerry Goldsmith returned to scoring Star Trek, the musical material

from the frst flm came with him. Klingons feature extensively in Star

Trek V, but their alien identity is eroded over the course of the flm as

the humans and Klingons unite in the face of another alien of greater

alterity.

Goldsmiths Klingon theme manifests itself for their frst appearance

[00:23:00], albeit in a faster tempo. The theme is embellished with

alterations in orchestration and rhythmic variations. An instrument

resembling a shofar is added to the Klingon material, playing a brief

ascending fgure over the theme, approximating tonic, fourth and ffth

scale degrees.

As the Klingons alterity is dissolved, so their musical identity is

de-Othered. At the climax of the flm, the Klingons aid the humans

and the two species are equated as fundamentally similar. The Klingons

appear with their theme in full at 1:30:40, with antiphonal imitation in

the upper strings. From this statement, it is subsequently rhythmically

augmented [1:31:12], heard in soli double reeds (in a crotchet, dotted

minim rhythm), repeated into rising sequences [1:33:10] and set in solo

clarinet with triadic major harmonic support from strings [1:33:40]. This

is followed by statements in the soft woodwinds with an upper string

countermelody [1:33:49]. The material is de-alienated progressively as the

Klingons are nullifed as a threat and shown to be more human: it

becomes harmonically secure; unusual or harsh timbres are eliminated;

and strident orchestration is softened. For the Klingons fnal appearance

in the movie [1:35:36], the theme does not sound at all.

38

Tim Summers Musical Depiction of the Alien Other

7:1 Spring 13 MSMI

Through the development of the Klingon musical material over the

course of Star Trek V, at least one reviewer felt Goldsmith to have

compromised the Klingon motif: [The] lighthearted variation on the

Klingon theme only goes to further belittle these characters, who sufer

massive indignation from their comedic on-screen antics. (Hirsch 1999:

559) The thematic development mirrors and accentuates the depiction of

the Klingons on-screen (Hirsch even asserts that the variations further

belittle[s] the Klingons). This keenly felt response to the treatment of their

thematic material reveals the extent to which these musical elements are

understood by viewers as part of the franchises depiction of the Klingons.

Star Trek VI (1991)

Star Trek VI is an allegory for the end of the Cold War: the crumbling

Klingon Empire is forced to consider peace with the Federation in

order to survive. In this flm they occupy the narrative role of acting

as allegorical representatives of the USSR. The force of this allegory

drives composer Clif Eidelmans music much more than a reliance on

any previous musical incarnation of the Klingons. Eidelman says:

I brought the Klingons right into the main title my Klingon theme

is very diferent from the past Klingon themes. Ive literally taken

Goldsmiths Klingon theme and put it up to the Klingons in Star Trek

VI and it works horribly, because the Klingons are not warlike in this

movie Its a diferent situation.

(Eidelman quoted in Altman 1993: 10)

Eidelman is aware of how the Klingons musical identity has to be

altered for the allegory at hand. As Wagner and Lundeen comment, Star

Trek employs its own racial constructs in various ways depending on the

narrative contexts A given identity may be set within diferent semiotic

structures depending on the story-telling context. (1998: 1667) The music

brings to bear its own semiotic and aesthetic forces in the same manner.

Two musical ghosts stand behind Eidelmans Overture (main title

theme, Figure 23), the openings of both Stravinskys Firebird (1910, rev.

1945) and the frst movement of Shostakovichs Tenth Symphony (1953).

For many listeners, both the music of Stravinsky and Shostakovich might

stand as representative of archetypal Russian music. These intertextual

references frmly establish from the outset the allegorical function of the

Klingon identity in this flm.

Eidelman introduces another aspect of the species into the musical

depiction through the inclusion of a chorus that chants Shakespeare in

Klingon. This distinct sonic articulation of alterity (through an unintel-

ligible language) is most evident when wrongly convicted humans enter

39

Tim Summers Musical Depiction of the Alien Other

MSMI 7:1 Spring 13

a prison [00:55:05] and the chorus comments taH pagh, taH be (To be,

or not to be). The percussive language is brought into the domain of

the score as part of their musical voice.

To maintain continuity of identity, Eidelman retains some elements of

earlier musical depictions of the Klingons, such as high-pitched drums,

unusual woodwind instruments (overblown screaming ffe, giant pipe,

bass fute) [00:27:20] (DVD Special Features), waterphones [00:34:30],

low drums and metallic sound-elements (cymbal scrapes) [00:27:34], and

a tonic-dominant rising brass fgure [00:28:00]. By repositioning the

Klingon musical identity, Eidelman parallels the flm in rendering the

Klingons as familiar, but in a new narrative role. Not so much revisionist

as multidimensional, the music ensures that character fdelity is retained

while telling a new, signifcant story.

Later Films

Eidelmans Klingon music was the last distinct musical identity for these

aliens to feature in the flms: no signifcant musical material is constructed

for the Klingons in the latter fve flms, although, in his score for Star

Trek: First Contact (1996), Goldsmith briefy cites his Klingon theme upon

the introduction of the Enterprises resident Klingon, Worf (Michael Dorn)

[00:09:29+], as a sort of musical cameo. Even if these musical identities

were not being sounded in the cinema, however, music for Klingons was

being developed in a diferent medium.

Figure 23: Star Trek VIs Overture (from audio transcription and

composers sketches in DVD Special Features).

40

Tim Summers Musical Depiction of the Alien Other

7:1 Spring 13 MSMI

Television Series (19872005)

Both the The Next Generation (TNG) and Deep Space Nine (DS9) television

series regularly featured episodes concerning Klingons. Just as particular

writers would frequently script such episodes, specifc composers (Ron

Jones and David Bell) were often assigned to Klingon stories (Bond 1999:

169, 190). Unlike 1960s television, each episode of Star Trek since 1987

has featured a newly written score. With multiple composers writing for

the aliens, a coherent, but multidimensional and evolving musical identity

was created for the Klingons. Each composer interpreted and defned

this identity in their own way.

Ron Joness score for Heart of Glory (1988) marks the frst signifcant

musical depiction of Klingons in TNG.The score is infused with Goldsmiths

Klingon material, which is melodically developed. Although in 1988,

Horners evil Klingon music provided a more recent Klingon identity,

Goldsmiths theme is more appropriate for TNGs depiction of Klingons.

While Paramount Television provided (for a television series) a generous

budget for the music of The Next Generation, the more limited fnancial

resources available to television productions in comparison with flm

demanded that Jones use a smaller orchestra than Goldsmith, resulting

in a noticeably thinner texture. Jones develops Goldsmiths material by

countering the rising ffth with a descending ffth beginning a semitone

above the end of the ascending ffth. A second fgure is heard in a higher

register, again beginning with Goldsmiths rising ffth, this time continuing

with another rising ffth beginning on a semitone higher than the end of

the frst interval. Jones reports that the development was shaped by his

use of an alphorn, which had a limited choice of pitches (interviewed in

Bond 1999: 181). This new variation on Goldsmiths theme would fnd

signifcant use in later scores. I have termed this motif X in its two

forms: X

1

(descending) and X

2

(ascending) (Figures 24 and 25).

Figure 24: Figure X

1

: descending.

Figure 25: Figure X

2

: ascending.

TNGs Klingons are diferent from those of the flms or TOS: they are

allies of the Federation and are carefully culturally textured, in comparison

41

Tim Summers Musical Depiction of the Alien Other

MSMI 7:1 Spring 13

to being basic villains or allegory-heavy characters. Correspondingly, the

music seeks to move from a barbaric primitivism to a more pastoral

primitivism through instrumentation such as the alphorn, a traditional

Western musical marker of rustic/romantic primitivism. Motivically, the

archaic elementary character of the ffth is combined with the alienating

strangeness of the semitone interval, shifting the musical identity.

The format of the television series allows space for the development

of a fctional species and, with this evolution, musical depiction also

can change. Just as Star Treks narrative intertextuality operates between

television and flm, so the musical intertexuality clearly fows between

the two media as musical material from flm is cited and developed

in television episodes. Joness second season Klingon episodes elaborate

his Klingon theme variations, based around motif X. In A Matter of

Honor (1989), X is placed in sequence [13:28], treated in retrograde

[17:35], verticalised into block chords, made into an ostinato motif [27:00]

and harmonised with parallel ffths [17:35+]. A minor third element is

introduced [19:00], later integrated to extend X

1

by continuing with

another rising ffth fgure at a distance of a minor third below the last

[41:09]. Sometimes, X is fragmented into three-note units, across the

rising gesture [27:00]. With such basic motivic material, a huge variety

of variations becomes possible.

These musical variations are often dramatically motivated. The more

similar these The Next Generation Klingons are seen to be to those in The

Motion Picture (1979), the closer the music is to direct citation of the flm

score. This is most clearly illustrated when time-trapped Klingons from

The Motion Picture-era are encountered in The Emissary (1989) or when

the Klingons in A Matter of Honor [27:54], like those in the opening

moments of The Motion Picture, prepare to engage in inter-ship combat.

The thematic variations in Ron Joness The Next Generation scores are not

limited to simply describing how similar, or how diferent, the on-screen

Klingons are to the Klingons in TMP. Jones uses the theme for a variety

of expressive functions. In The Emissary, for example, he presses the

Klingon material into service as a cantabile love theme for a romance

between Klingons [17:03] (Figure 26).

Figure 26: Love theme from The Emissary [19:45].

42

Tim Summers Musical Depiction of the Alien Other

7:1 Spring 13 MSMI

However, Jones was not the only composer who wrote for Klingons. Sins

of the Father (1990), scored by Dennis McCarthy, references established

thematic material [00:57], though does not employ Joness motivic web.

McCarthys style of extended, non-repetitive melodic strands over sustained

textures lends itself well to integrating the rising ffth or Joness X

1

motif

into the melody. These strands are frequently harmonised by parallel ffths.

McCarthys low-brass, open ffth sustained harmonic support provides a

textural-timbral fabric that also evokes Klingon-ness from previous flm

and TV scores. Goldsmiths material lives on through the incorporation

of low brass/horn timbres and open ffth intervallic choices, but the alien

identity is expressed in a diferent fashion to its motivic incarnation in

Joness work.

In Jay Chattaways Klingon scores (such as Birthright 1993) no

dominant Klingon theme is forthcoming, merely Klingon-sounding

material. Chattaway maintains emphasis on low brass, open ffth harmonic

underpinning and, at times, rising ffth intervals [e.g. Birthright Part

II 36:02]. Chattaway was not unaware of past Klingon-associated

music; rather, he interpreted the precedent diferently from Jones. He

comments, We wouldnt know what Klingons heritage would sound like

without Jerrys wild sonorities of Klingon music and percussive qualities

( Jerry Goldsmith: A Tribute). Chattaways choice of language reveals his

understanding of their musical identity in terms of timbre and harmony,

rather than through melodic motifs.

Joness motif-centred scoring style contrasted with that of Chattaway

and McCarthy, and he engages in a style of obvious musical narration

that is largely absent in the scores of other composers (such as musically

pre-empting the Klingons plot involvement in Reunion (1990), mere

seconds into the episode [00:17]). Jones was ultimately dismissed from The

Next Generation due to creative diferences with the producers concerning his

approach to scoring and, in particular, the degree to which it contrasted

with the other composers music (Bond 1999: 170). The level of musical

variation appropriate within a single television series would seem, therefore,

to have limits.

References to real-world Earth musical culture are also used as part

of the depiction of the fctional Klingons. The representation of Klingon

culture draws infuence from several Earth traditions, including Norse

myths, which appears not only in the use of the lur-like alphorn and

a concomitant emphasis on the low brass,

14

but also through allusion

to Wagner. Diegetically performed Klingon opera, such as Aktuh and

Maylota (recalling the duo-titled Tristan and Isolde) is abrasive and sung

with extreme ferocity, as in the popular caricature of Wagnerian opera

(heard in Unifcation II [TNG 1991], see later). For Blood Oath (DS9

14

The lur is a traditional

Scandinavian instrument,

similar to the alphorn and

features in Nordic sagas

(Vollsnes et al. 2009). The

alphorn also has associ-

ations as an established

musical (romantic) topos

of pastoral simplicity/

rusticity.

43

Tim Summers Musical Depiction of the Alien Other

MSMI 7:1 Spring 13

1994), Gtterdmmerung was played on set during shooting, to infuse an

operatic mood to the proceedings (Erdmann 2000: 132). Regarding The

Sword of Kahless (DS9 1995), composer David Bell has said, I saw

these characters as very Wagnerean [sic] so I used Wagner opera

vocabulary in the orchestrations, and I actually used Wagner tubas in

the score (Erdmann 2000: 291). Bell continued to employ Wagner tubas

for Klingon episodes, such as Sons of Mogh (DS9 1996) and using

additional low brass performers on Soldiers of the Empire (DS9 1997)

(ibid.). Bells Wagner opera vocabulary seems to fnd voice primarily in

the placing of melodic material in low registers (a rarity for post-1987

Star Trek scores) [Sword of Kahless: 19:57, 28:00, 42:20]. Such orches-

tration provides weighty expansiveness, monumentalising the proceedings

in a similar way to operatic practice. In Soldiers of the Empire, the

underscore even appears to accompany the singing of Klingon-language

diegetic songs as one would expect in a musical or opera flm [15:58,

38:55].

In the frst season of Star Treks prequel series, Enterprise (20012005),

the Klingons are not accompanied by their known musical identity:

they have not yet grown into the role with which we are familiar.

Neither Velton Ray Bunchs score for Marauders (Enterprise 2002), nor

McCarthys for Sleeping Dogs (Enterprise 2002) contain motivic material

from previous Klingon incarnations and the open ffth, low brass emphasis

is less musically prominent.

The episode Judgement (Season 2, 2003), however, indicates a change

in scoring strategy. This episode parallels the flmic presentation of

Klingons in Star Trek VI (1991) by including scenes set in the same

locations and environments as the 1991 flm. Bunchs score pays homage

to that of Eidelman: the Klingon world is given a recurring motif (played

in low strings, later adding brass), which is frst heard before the opening

credits, and used in variation throughout the episode (Figure 27). Bunch

also uses the marcato low string accents, the weaving and winding solo

upper string lines [07:28+] and the tremolo string sequences [09:00], which

feature in Eidelmans score.

Figure 27: Teaser cue from Judgment, introducing the main Klingon motif

for the episode.

44

Tim Summers Musical Depiction of the Alien Other

7:1 Spring 13 MSMI

A signifcant musical presence is appropriate for scenes imitating those

from theatrical flm, to approach the same aesthetic. The music connects

the two incidents and casts the Klingons into their familiar roles, evoking

the Klingon musical identity to a much greater degree than earlier in

the prequel series.

Later episodes of Enterprise, such as Afiction (2005) and Divergence

(2005) (scored by Bunch and Chattaway respectively) begin to create a

musical proto-identity as they present a coherent soundworld for the

Klingons, emulating Judgement. Low brass chordal swells featuring open

ffth spacings are prominent [Afiction, 22:57+] and pitch selections

in both scores concentrate on the frst, second, minor third and ffth

degrees of the scale. There are similarities between the music of these

Enterprise episodes and those of TOS, such as the percussion-driven and

highly rhythmic cues, and soloistic woodwind writing (such as the bass

clarinet at 11:57 in Afiction).

The prequel series, both musically and generally, articulates a Klingon

identity that gradually develops back toward the more familiar depictions

of these aliens. The underscore, however, is not the only music used to

characterise the Klingons.

Source Music

Given the importance of music in human cultures, the omission of music

in a depiction of an alien culture would be curious. In this way, alien

music may be harnessed in the service of realism. The cultural output

of an alien species is part of the way the viewer understands the aliens.

Klingon source music generally constitutes either Klingon opera or

drinking/battle/story songs. Such songs feature intermittently in post-1987

Star Trek. One drinking song, shown in Figure 28, is heard in episodes

of diferent series. This reprise provides textual unity across television

series and assists in the creation of a persistent, coherent culture in the

franchise universe. Songs also serve a semi-ritual function, for example,

The Klingon Warriors Anthem (Soldiers of the Empire, DS9 1997) is

sung before a ship enters battle (Figure 29). This song originated in the

videogame Star Trek: Klingon (1996), before being inducted into the ofcial

franchise lore through inclusion in a television episode. The music uses

simple repeated gestures and is sung in an impassioned, rowdy manner.

Both songs are in variation form, with repeated phrases, giving a folk

music quality to the pieces. The Klingon songs feed into a depiction

that cultivates a historical and pastoral/rustic image of them.

Klingon opera is frst heard in Unifcation II (TNG) where excerpts

from Aktuh and Maylota are sung. The accompaniment consists of

45

Tim Summers Musical Depiction of the Alien Other

MSMI 7:1 Spring 13

synthesised repeated minor triads in low registers, while the vocal lines are

often indefnite in pitch and contain ferocious vaulting intervallic gestures,

a kind of extreme bel canto combined with Sprechstimme. A complexity is

brought to the depiction of Klingon music, however, when the Klingon

opera duet heard in Looking for parMach in All the Wrong Places

(DS9 1996) is of a very diferent musical style. Described in the script as

a Klingon La Boheme [sic] (Kindya et al. 1999), the music is similar

to Puccinis style in its bel canto, cantabile melodies, harmonic modulation

scheme and grandiose non-synthesised orchestration. The accompaniment

resembles the non-diegetic underscoring used in Klingon episodes an

emphasis on low brass, timpani and open ffth harmonic spacing.

A Klingon street opera is seen in Firstborn (TNG 1994), in which

members of the audience enter the performance space and sing traditional

refrains as responses to the principal performers. The vocal phrases are

accompanied by drums, synthesised bass pedal notes, didgeridoo-like

instruments and a marimba sound. The rusticity and ritual central to

the Klingon identity are emphasised in this depiction.

Klingon instruments accompany singing (the concertina and guitar:

Melora (DS9 1993, Playing God (DS9 1994)) or rituals (the wedding

drums in You Are Cordially Invited (DS9 1997)). The choice of

instruments associated with folk music again emphasises the rustic

dimension of the Klingon identity.

Vocal musical genres provide the opportunity to display the Klingon