Professional Documents

Culture Documents

In Conversation: John English On The Origins of The Arctic Council

Uploaded by

NorthernPAOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

In Conversation: John English On The Origins of The Arctic Council

Uploaded by

NorthernPACopyright:

Available Formats

22 Northern Public Affairs, September 2013

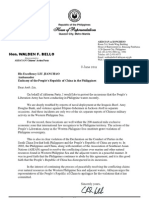

IN CONVERSATION

Professor John English

Oor citr, )rolc Sooio, / oit/ Prfr )/o Eoli/ ooot /i oo o/,

Ice and Water: Politics, Peoples, and the Arctic Council. It will be published

o, Jllo Loo ooc io tr O.tor 8, !013

J

erald Sabin: Your new book, Ice and Wa-

ter, comes out in October. In the book,

you argue that Canadas relationship to the

Arctic Council under Prime Minister Ste-

phen Harper has shifted considerably since

the 1990s. Can you take us back to the begin-

ning of the Council and to how it emerged?

John English: The Arctic Council starts with the last

years ol the Colo War. I creoit |lormer Soviet Union

President Mikhail] Gorbachev with giving the ini-

tiative for the Arctic Council by talking in October

1987 about an Arctic zone ol peace, about open-

ing up the Arctic more widely, and about contact

between Arctic states being essential. It immeoiately

hao an impact. In NATO Heaoquarters ano else-

where this was treated skeptically not suprisingly,

given the history. But the Iinns took up Gorbachev`s

idea and proposed an Arctic environmental organi-

zation ol some kino or another. It was very vague at

the start.

That was the Arctic Environmental Protec-

tion Strategy (AEPS), a precursor to the Arc-

tic Council. What was Canadas position on

this Arctic zone of peace and the Finnish

proposal?

The Canadians were thrown off course by the end

ol the Colo War. Our Delence Department`s 1987

White Paper was a very hard lined and included

apropos the Arctic nuclear submarines, which

would be in the North to watch the other Soviet

ano American submarines. This was going to be

our commitment to an intensineo Colo War, which

seemeo to be the way things were going since 198!.

Then there was this suooen change.

The Canadians were surprised by the Finnish

initiative. The Iinnish proposal was unoerstanoable,

because the Finns wanted every possible opportu-

nity to bring the Soviet Union out of what it had

been. What the Iinns was proposeo an environmen-

tal agency nothing about security, nothing about

social concerns, and nothing about the human ele-

ment ol the Arctic.

The Canadians had been very active in the

1980s in the North with an Arctic environmental

strategy ol their own. Much ol this work hao been

done in the Department of Indian and Northern

Development ,DIAND,. When the Canaoians saw

|the Iinnish proposal|, they saw it as an opportunity.

Canada had been doing a lot of international work

on pollutants. The notion was that the Arctic was

a sink that attracted pollutants from the rest of the

world, so the AEPS was timely from the Canadian

point ol view.

1

How did the AEPS transform into the Arctic

Council as we know it today?

In 1982, |Frime Minister Brian| Mulroney hao gone

to the Arctic ano proposeo an Arctic Council ol

some kino. Again, he was very vague about it. In

Canada, a group of people took up this challenge to

lorm an international Arctic organization. A gath-

ering of Arctic nations had been proposed as ear-

ly as the 1970s by Maxwell Cohen a Canadian

lawyer of great eminence and our most prominent

international lawyer at the time. He proposeo to

the Canadian Institute of International Affairs that

something like this be createo. At University ol Ot-

tawas Faculty of Law, Donat Pharand had proposed

an Arctic treaty similar to the Antarctic treaty dating

lrom the 190s. So, these ioeas were in the air ano

Canaoians were central to the oiscussion.

Conferences took place here in Toronto, funded

mainly by the Walter and Duncan Gordon Founda-

tion a foundation which has been long active in

the North ano a special Northern locus. They paio

lor the setting up ol an Arctic Council panel. Kyra

Montagu, who is a Gordon daughter, was especially

active in that respect. Iranklin Grilnths, the Univer-

sity ol Toronto prolessor, was to be the Chair. He

recognized right from the very start that it would be

impossible to have this group of Toronto academ-

ics and Tom Axworthy a former aide to [Prime

Eoli/` o/ oill o ooli/c io O.tor o, Jllo Loo (oo ioriot f Pooio Coooco,.

2! Northern Public Affairs, September 2013

Minister| Fierre Truoeau in the leao. This hao

to have more of a Northern focus and Northern

peoples hao to be renecteo in its composition ano

outlook.

Grilnths proposeo Rosemarie Kuptana lor the

position ol Co-Chair. Their initial interest was in

a zone ol peace ano the oemilitarization ol the

Arctic. During the 1980s, the Inuit Circumpolar

Conlerence ,ICC, were very active. Mary Simon

became especially prominent in the early meetings

|leaoing to the AEFS| as presioent ol the ICC. At

the Canadian meeting in Yellowknife in the lead up

to the signing of the AEPS, Mary intervened and

said that she was not going to sit at the side but that

she would sit at the table with the state representa-

tives. Irom that point on, |Inoigenous participation|

became a central matter lor oiscussion. She wrote to

the Swedish Foreign Minister and said that [Indige-

nous peoples| must be at the table. He took a long

time to answer her, as he consulted other delega-

tions. The Canaoian government supporteo her ano

[the Walter and Duncan Gordon Foundations] Arc-

tic Council panel took that up as a cause. Graoually,

the concept developed of permanent participants by

about 1991-1992.

The AEPS was signed in 1991. Was Canada

sntisBod with thnt outcono, or did thoy wnnt

something more?

The Canadian government, after Mulroney made

this pledge for an Arctic Council, tried to develop

it. Canaoa wanteo it to be a comprehensive panel

to consioer all matters Arctic. In terms ol a treaty,

it was uncertain, but Canada did want an organiza-

tion and wanted it to go beyond the narrow environ-

mental locus ol the AEFS which was too scientinc

ano sterile. It oion`t have the people involveo.

The Arctic was different from Antarctica, which

hao no people. It was a oillerent composition. There

were clear sovereign states and clear cases of sov-

ereignty in the North. By 1991, |the AEFS| was

moving forward pretty quickly, but then it slowed

oramatically.

There were three principal reasons lor this. One

was the United States, who just did not like the Arc-

tic Council ioea. They oon`t really see themselves

as an Arctic nation. They thought this coulo inter-

lere with American loreign policy. They also oion`t

like the idea, in this post-Cold War era, of setting

up new international organizations as it was just too

nuio. They were, it is lair to say, in opposition to an

Arctic Council. Secono, within Canaoa itsell, those

were the years ol our constitutional oebates. We lost

our locus. The government oion`t want to push it.

The Arctic Council panel was upset with this. Ano

the third reason was the position of our Indigenous

peoples. The Canaoian government supporteo them

as permanent participants. Not all parts ol govern-

ment oio, however. In Ioreign Allairs there was clear

doubt about whether we should have non-govern-

mental bodies or individuals at tables where states

were present. In other countries, Norway is olten

mentioneo, there was opposition to this ioea. Mary

Simon, lor example, recalls that opposition. Every-

thing ooesn`t move very lar.

How was this inertia overcome?

Well, the Liberals come to power in 1993. They

talked about a new Northern foreign policy and had

promiseo a new Circumpolar Ambassaoor. This was

one of their pledges that they had made before the

election campaign. They appointeo Mary Simon as

their nrst Circumpolar Ambassaoor, ano the specinc

instructions for her were to create the Arctic Coun-

cil. It was a bipartisan issue the Liberals support-

eo this ano oion`t have opposition.

Ano it was part ol the mooo ol the time. The

worlo was changing lunoamentally. The Uniteo Na-

tions was more important than ever. There was talk

ol something calleo human security oevelopeo by

the United Nations a security beyond the bound-

aries ol the state ano concern lor inoiviouals. This

was something picked up especially by Lloyd Ax-

worthy when he became Minister of Foreign Affairs

in 199o. This was all heighteneo by the various ca-

tastrophes of the time, whether it Somalia, Rwanda,

or the lormer Yugoslavia. How can we get beyono

state sovereignty, as Axworthy woulo olten say.

So, in 1996 when Axworthy came, [Prime Min-

ister Jean] Chrtien met [President Bill] Clinton and

proposeo the Arctic Council again. This became part

ol Axworthy`s human security initiative. So there is

no ooubt that it was the Canaoians who pusheo it.

The United States was not interested, and proba-

bly opposeo most ol the time. Ano in Europe itsell,

the Norwegians had organized a European barrens

council, which was very active and fairly success-

lul in oealing with human security questions. The

AEPS had been created too, and the Americans said

somewhat justinably that we shoulo see how these

things work belore we go lurther. But the Canaoians

by this point had built up momentum, appointed a

Circumpolar Ambassador with an Arctic Council

mandate, and beyond that, there was strong support

lrom Inoigenous peoples.

25 Northern Public Affairs, September 2013

How did Indigenous peoples propel the cre-

ation of the Arctic Council?

What was very signincant was the role playeo by In-

oigenous peoples themselves. They came to take up

the creation ol an Arctic Council as their cause. Not

at the very nrst, when it seemeo like they were ex-

cluoeo. But it appeareo to them by 1992-199!, that

this was a real opportunity.

This is an organization that would never have

happened if the Inuit Circumpolar Council had not

taken the leao. So, Inoigenous people, they creat-

eo the Arctic Council. You oo get a sense now that

others have taken it over, and probably pushing the

direction, but Indigenous peoples are still there and

have a prominent place at the table.

The Arctic Council was eventually established

unoer the Ottawa Declaration in 199o. The Liberal

government continued to support the work of the

Council throughout that time, appointing Jack An-

awak as Circumpolar Ambassaoor in 2003. In 200o,

the Conservatives were electeo to their nrst minority

government, and they promptly axed the position

ol Circumpolar Ambassaoor. How oio changes in

Canadas foreign policy under Prime Minister Ste-

phen Harper affect the Arctic Council and the work

it was doing?

One gets the sense that when they came into

olnce they haon`t thought very much about it. The

Conservatives hao thought a lot about the Arctic.

Prime Minister Harper had given a speech in 2005

that Arctic sovereignty was our principal concern

and we must defend it and rank it high in our de-

lence pronle. Seconoly, when he came into olnce

he attacked the American Ambassador about some

musings the Ambassador had on the Northwest Pas-

sage. So, it was clear that he was uninteresteo in the

Arctic, but that the Arctic Council oion`t really nt

ano the Arctic Ambassaoor was abolisheo. They

said that it didnt really give us very much, which

was quite an insult to Mary Simon and Jack Anawak

who hao been ooing it.

I think the Conservatives saw it as a Liberal ini-

tiative. I think it is lair to say that by 200o, the gov-

ernment itself had been less active in the Council

than it hao been in the 1990s. It was more ol our

game then, but a change came with 9/11 and so

much else. As one prominent Conservative tolo me,

they were told to call the Arctic Council the Mul-

roney Initiative which technically is true as Mul-

roney hao proposeo it nrst.

Well, you could say that the Conservative

Party has had a long relationship with the

North, predating even Diefenbakers North-

ern Vision. There has been a close relation-

ship between the Conservative Party, the

North, and political and economic develop-

ment. So, why wasnt the Arctic Council em-

braced? Was it just its Liberal origins or its

international outlook?

I think that was it, it was what surrounded the Arc-

tic Council. The human security rhetoric. The lact

that the Uniteo States hao opposeo it in 200!, when

the Arctic Council ran into trouble. What put the

Arctic Council on the map in the nrst part ol this

century was the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment.

It got into the question ol climate change. Climate

change was controversial with the Bush Administra-

tion and, quite frankly, controversial with the Harp-

er government when it came in too. So because ol

that mixture of things, it is not surprising that the

Conservatives oion`t have an interest in the Council.

Where the Harper government did show inter-

est was on the military sioe. It is a very high priority

for the Canadian Forces and incidents such as the

Russian nag planting at the North Fole. The para-

dox is that in the Arctic Council, Canada and Russia

are now often on the same side, such as vetoing the

participation of the EU because of its stance on fur

ano nsh. We`re also on the same sioe because both

have Arctic sea passages, and the other states dont

necessarily recognize their national rights in those

specinc passages.

So, why have the Conservatives embraced

tho Arctic Council nt this spociBc nonont in

its history?

Well, it`s the major game in town. By 2009-2010,

the Arctics prominence in international politics had

become so much more obvious and so much more

impossible to avoio. The neeo lor collaboration hao

become so much stronger. I mentioneo the incioent

ol Russia planting its nag in 2007. In response, the

Arctic coastal nations of which Canada is one

made a declaration saying that we dont need

a treaty, we can hanole this ourselves. We`re going

to move lorwaro by collaboration, not by connict.

The incioent ol the nag shoulo not be an inoication

that there is connict among us, rather we will stano

together, we will work together, and we will settle

things through what is the Arctic Council.

When the Arctic Council was being formed, the

Finns looked around and asked how many interna-

tional agreements have the Arctic as a prominent

part or have agreements that specincally cover Arc-

tic states? There was only one and it dealt with polar

bears. In all the others, the Arctic was a subset or a

clause like in the United Nations of Law of the Sea its

just a clause. So, there was a neeo to treat the Arctic

oistinctly.

Alter 2008, it became impossible to ignore the

Arctic lor all ol these states. The pressures towaros

collaboration were much greater because there were

threats lrom the outsioe. In 2010, Hillary Clinton

came to Ottawa and she blasted the Canadian gov-

ernment lor only having the coastal states there.

This was a great irony because it was her husbands

aoministration that hao opposeo the Arctic Council.

At Kiruna, non-Arctic states like China, In-

dia, and Japan were made permanent ob-

servers. How has the Council changed in the

past few years?

The Scandinavians have Chaired the Arctic Coun-

cil recently, and as they always manage to do, they

made it a very effective organization that started to

matter more. When I was at Kiruna this year, one

of the veteran delegates from the Arctic Athabaskan

Professor John English

27 Northern Public Affairs, September 2013

Council said the Council really started to change

when the Scanoinavians took over. It hao been so

much more ol a talk shop belore that. Now, you see

things getting done, such as search and rescue agree-

ments. There is a lot going on behino the scenes.

The meetings used to be very small and now

they are massive. The New York Times sent a corre-

spondent! You know, it is only the Canadian news-

papers that oion`t seno any corresponoents. All ol

the major European outlets were there. Even John

Kerry was there. Until Hillary Clinton came, the

US Secretary of State never attended the ministe-

rial meetings. Irankly, when the Arctic Council was

formed, the only foreign minister who was there was

Lloyo Axworthy. It has become a much more serious

organization.

At Kiruna every country, bar Iceland because

ol an election, hao their loreign minister there. That

includes [John] Kerry and [Russian Foreign Min-

ister Sergei] Lavrov, and the Scandinavian foreign

ministers. It was Chaireo by Carl Bilot, a lormer

Prime Minister of Sweden and one of the great in-

ternational diplomats of our time in the former Yu-

goslavia. He is a man ol tremenoous weight he`ll

get all his phone calls answered if he calls any capi-

tal in the worlo. So, this is an organization that has

suddenly moved into the major league because the

playing nelo has changeo so oramatically. I woulon`t

be surprised if in the next two or three years it

depends on external circumstances to see leaders

coming together ol the Arctic Nations.

Before Kiruna, the outstanding issue was what

to oo about the observers. That touches on our In-

oigenous peoples ano permanent participants. They

had a sense that if you admit observers of the size

and weight of China, it will affect the operations of

the Council. Having hao some oiscussion with the

permanent participants, there was that sense, but

there was a recognition that, as the Arctic becomes

increasingly signincant in international politics, to

have a Chinese voice vetoed or absent would be

very oilncult. There was an acceptance, with a small

amount ol reluctance, to bring China into it.

In his lntost cnbinot shuIBo, tho Prino Min-

ister moved Leona Aglukkaq from Health to

the Environment. What do you make of that?

I think it is interesting that she was moved to Envi-

ronment. In her speech at Kiruna, the Canaoians

emphasized what one could call domestic matters

how people live in the North. Whereas Kerry,

for example, talked almost exclusively about climate

change. There was a huge oillerence there. She nev-

er mentioned climate change once, he mentioned

it continuously. It`s not that she`s oenying there are

changes, but she`s saying let`s locus on the people.

Ano that is within the Canaoian traoition.

Having said that, a lot of what the Arctic Coun-

cil ooes is becoming very high politics. The other

representatives at the Council are representatives of

Ioreign Olnces ano Ioreign Ministries. The lact that

Aglukkaq was in health meant that her domestic re-

sponsibilities were pretty far from an Arctic perspec-

tive. In Environment, well it is very clear that the

environment in the Arctic is being allecteo. Even the

oil companies are saying that its being affected

they can orill more easily because the ice is receoing.

In Environment shell have a more direct relation-

ship to Arctic issues.

Why should Northerners be keeping their

eyes on the Arctic Council?

They should be keeping their eyes on the Council

because it will allect how they live. It is a very simple

answer. The Arctic Climate Impact Assessment hao

a huge impact on the way the Arctic was perceived

as a canary in the mine shalt. Search ano rescue co-

ordination has a direct impact on individuals in the

Arctic ano I oo mean inoiviouals.

I was impressed by the buzz at the side of the

meetings in Kiruna. It useo to be, I was tolo, that

the meetings were brief and low-level affairs among

people without the capacity to make oecisions. Now

people come there, including business people trying

to sell things, and it is clearly a place where some-

thing is happening. That kino ol happening is going

to affect how people live on the ground in Nunavut,

the Northwest Territories, ano elsewhere. Ano it is

the only organization I can think of which has a sig-

nincant presence ol non-state actors Inoigenous

peoples at the table. It was the nrst, ano as Lloyo

Axworthy said in 1996 when it was founded, this will

be a preceoent, ano that may well be.

John English is a professor of history at the University of

Waterloo and a former MP. He is the author of the acclaimed

to-.loo oiro/, f Pirr Ellitt Trocoo, o/i./ .o-

prises Citizen of the World: The Life of Pierre Elliott

Truoeau, 1919-19o8 and the award-winning Just Watch

Me: The Lile ol Fierre Elliott Truoeau, 19o8-2000.

Footnotes

1. Negotiations began lor the AEFS in 1989. It was signeo

by Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, the So-

viet Union, Sweoen, ano the Uniteo States in 1991.

SWEDEN

T/ o/ f Ioo/oi rf.tio io lo/ Loctoor.

P

h

o

t

o

c

r

e

d

i

t

:

F

r

e

d

r

i

k

B

r

o

m

a

n

/

i

m

a

g

e

b

a

n

k

.

s

w

e

d

e

n

.

s

e

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Nation Within by Tom CoffmanDocument19 pagesNation Within by Tom CoffmanDuke University Press0% (1)

- Defining The North - Peter RussellDocument2 pagesDefining The North - Peter RussellNorthernPANo ratings yet

- Shanghai Cooperation OrganisationDocument11 pagesShanghai Cooperation OrganisationmrNo ratings yet

- Special Issue 2014 - Revitalizing Education in Inuit NunangatDocument92 pagesSpecial Issue 2014 - Revitalizing Education in Inuit NunangatNorthernPANo ratings yet

- LuckyrockDocument6 pagesLuckyrockNorthernPA100% (1)

- Tsilhqot'in Nation v. British ColumbiaDocument81 pagesTsilhqot'in Nation v. British ColumbiaNorthernPANo ratings yet

- Dear AndyDocument4 pagesDear AndyNorthernPANo ratings yet

- Special Issue 2014 - Revitalizing Education in Inuit NunangatDocument92 pagesSpecial Issue 2014 - Revitalizing Education in Inuit NunangatNorthernPANo ratings yet

- Mining in Caribou Calving Grounds: Can Nunavut Beat The Status Quo?Document7 pagesMining in Caribou Calving Grounds: Can Nunavut Beat The Status Quo?NorthernPANo ratings yet

- Northern Public Affairs Special Issue 2013Document64 pagesNorthern Public Affairs Special Issue 2013NorthernPA100% (1)

- An Interview With Christopher AlcantaraDocument5 pagesAn Interview With Christopher AlcantaraNorthernPA100% (1)

- Mary Simon: A Time For Bold Action On Inuit EducationDocument4 pagesMary Simon: A Time For Bold Action On Inuit EducationNorthernPANo ratings yet

- NPA Call For Submissions - Fall 2013 Literacy IssueDocument1 pageNPA Call For Submissions - Fall 2013 Literacy IssueNorthernPANo ratings yet

- Letter From The Editors - December 2013Document2 pagesLetter From The Editors - December 2013NorthernPANo ratings yet

- Yukon Budget Address 2012-2013Document40 pagesYukon Budget Address 2012-2013NorthernPANo ratings yet

- SPECADocument7 pagesSPECANorthernPANo ratings yet

- NPA Call For Research NotesDocument1 pageNPA Call For Research NotesNorthernPANo ratings yet

- NWT Devolution AIPDocument66 pagesNWT Devolution AIPNorthernPANo ratings yet

- AglukkaqDocument3 pagesAglukkaqNorthernPANo ratings yet

- CCARG Letter To Arctic CouncilDocument2 pagesCCARG Letter To Arctic Councilgladstone_joshuaNo ratings yet

- MayerReportonNunavutDevolution EngDocument48 pagesMayerReportonNunavutDevolution EngNorthernPANo ratings yet

- From The Yukon ArchivesDocument4 pagesFrom The Yukon ArchivesNorthernPANo ratings yet

- NPA Call For Submissions April 30Document1 pageNPA Call For Submissions April 30NorthernPANo ratings yet

- Mary River Final EIS Executive SummaryDocument148 pagesMary River Final EIS Executive SummaryNorthernPANo ratings yet

- Yukon Budget Highlights 2012-2013Document8 pagesYukon Budget Highlights 2012-2013NorthernPANo ratings yet

- Nunavut Devolution Protocol - EngDocument8 pagesNunavut Devolution Protocol - EngNorthernPANo ratings yet

- THE UN IN EAST TIMOR - Building Timor Leste, A Fragile StateDocument2 pagesTHE UN IN EAST TIMOR - Building Timor Leste, A Fragile Statejf75No ratings yet

- The Korean War and Its AftermathDocument27 pagesThe Korean War and Its Aftermathapi-252762357No ratings yet

- Dueck, Jennifer M. (2007) The Middle East and North Africa in The Imperial and Post-Colonial Historiography of FranceDocument16 pagesDueck, Jennifer M. (2007) The Middle East and North Africa in The Imperial and Post-Colonial Historiography of FranceSamu Suárez AcostaNo ratings yet

- Alan Collins State-Induced Security Dilemma PDFDocument18 pagesAlan Collins State-Induced Security Dilemma PDFCarlosChaconNo ratings yet

- Tony Clement Slush Fund DocumentsDocument5 pagesTony Clement Slush Fund DocumentscanadianpoliticsNo ratings yet

- Aligned But Not Allied: ROK-Japan Bilateral Military Cooperation, by Jiun BangDocument37 pagesAligned But Not Allied: ROK-Japan Bilateral Military Cooperation, by Jiun BangKorea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- Chapter 1 PDFDocument14 pagesChapter 1 PDFbeariehlNo ratings yet

- FMFRP 12-11 German Tactical DoctrineDocument95 pagesFMFRP 12-11 German Tactical DoctrineJoseph ScottNo ratings yet

- The An Glop Hone Problem in The Cameroon1Document42 pagesThe An Glop Hone Problem in The Cameroon1Julius CheNo ratings yet

- 15th SOM AnnexB Welcome Remarks Gov South SumateraDocument4 pages15th SOM AnnexB Welcome Remarks Gov South SumateraFauzan RahmanNo ratings yet

- Mod 1 0034to0037Document4 pagesMod 1 0034to0037Bren-RNo ratings yet

- Lme Daily Official and Settlement Prices: Lme Copper $Usd/Tonne Oct-11 Cash 3-Months December 1 December 2 December 3Document20 pagesLme Daily Official and Settlement Prices: Lme Copper $Usd/Tonne Oct-11 Cash 3-Months December 1 December 2 December 3baoanhnguyenNo ratings yet

- Imperialism Study GuideDocument3 pagesImperialism Study Guideapi-243105548No ratings yet

- PSCI-150: Introduction To International Relations Max Margulies Summer 2017, Session 1 Monday and Wednesday, 9:00 AM-1:00 PM Location: TBADocument5 pagesPSCI-150: Introduction To International Relations Max Margulies Summer 2017, Session 1 Monday and Wednesday, 9:00 AM-1:00 PM Location: TBAZorina ChenNo ratings yet

- The Berlin BlockadeDocument1 pageThe Berlin BlockadeSmita ChandraNo ratings yet

- A Clash of Cultures Civil-Military Relations During The Vietnam War (In War and in Peace U.S. Civil-Military Relations) PDFDocument213 pagesA Clash of Cultures Civil-Military Relations During The Vietnam War (In War and in Peace U.S. Civil-Military Relations) PDFPaul GeorgeNo ratings yet

- China Analysis Taiwan Between Xi and TrumpDocument14 pagesChina Analysis Taiwan Between Xi and TrumpArio AchmadNo ratings yet

- Waltz Kenneth Structural Realism After The Cold War PDF (Highlights and Notes)Document4 pagesWaltz Kenneth Structural Realism After The Cold War PDF (Highlights and Notes)ElaineMarçalNo ratings yet

- Cia Intelligence MemorandumDocument11 pagesCia Intelligence Memorandumreyniel2ndaccNo ratings yet

- Malaysian Studies Assignment 3Document3 pagesMalaysian Studies Assignment 3Kai Jie100% (1)

- 2020 CH 4 Sec 1 Qs 3 To 7 and VocabDocument19 pages2020 CH 4 Sec 1 Qs 3 To 7 and VocabMeeraNo ratings yet

- Armour - BazaDocument273 pagesArmour - BazaJakub MroczkowskiNo ratings yet

- Protest Letter For Chinese EmbassyDocument1 pageProtest Letter For Chinese EmbassyBlogWatch0% (1)

- (Adelphi Series) Andrew Cottey-Reshaping Defence Diplomacy - New Roles For Military Cooperation and Assistance-Routledge (2004)Document85 pages(Adelphi Series) Andrew Cottey-Reshaping Defence Diplomacy - New Roles For Military Cooperation and Assistance-Routledge (2004)Andri Tri Saputra100% (1)

- Sardinian Army 1730-1773Document3 pagesSardinian Army 1730-1773Giovanni Cerino-BadoneNo ratings yet

- Selected Working Paper Vol - 1Document211 pagesSelected Working Paper Vol - 1ထြန္း လင္းေအာင္No ratings yet

- Colonialism Vs Imperialism PDFDocument2 pagesColonialism Vs Imperialism PDFJessicaNo ratings yet

- IndiaDocument32 pagesIndiaRahul ChakrawarNo ratings yet