Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Is Determination of Employment and Termination of Contract The Same in Meaning and Implications

Uploaded by

mrlobboOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Is Determination of Employment and Termination of Contract The Same in Meaning and Implications

Uploaded by

mrlobboCopyright:

Available Formats

A

rticle

Your Contractual Questions Answered

Is Determination Of Employment And Termination Of Contract The Same In Meaning And Implications?

By The Entrusty Group Entrusty Group, a multi-displinary group of companies, of which, one of their specialisation is in project, commercial and contractual management, has been running a regular contractual questions and answers section for Master Builders members in the Master Builders Journal. In this instalment of this series, Entrusty Group will provide the answer to another frequently asked question above.

ne of the common problems in the construction industry which usually has serious implications on the project and the parties concerned is termination of contract or determination of employment by the Employer or Contrac tor. The ac tion of determination or termination almost always brings the contracting parties into arbitration or litigation. However, although the implications are serious for the parties concerned to arrive at such a precarious state, many players in the construction industry still lack the understanding and appreciation of the difference between determination of employment and termination of contract. Often the term has been construed, mistakenly, as being the same in meaning and implications when in fact they are somewhat different and can be well distinguished. Further, it is often said that a contract has been determined or the Contractors employment has been terminated, which in the strictest sense and interpretation, is wrong. It means that although the employment of the contractor has ended, the contract nevertheless still subsists but the rights and obligations of the parties are governed by the post determination provisions as set out in the contract.

This article serves to clarify and act as a guideline for Employers and Contractors including Sub-contractors to exercise their rights contractually and/or at common law, carefully and with caution when a contracting party chooses to embark on such drastic recourse or remedy for breach committed by the other party in the contract.

What is Determination of Employment?

When used in the contex t of construction contracts, the word determination is employed in connection with the bringing to an end the Contractors employment under the particular contract. In determination, it is the Contractors obligation and responsibility to carr y out the works under the contract that is terminated and not the contract. The contractual and common law rights of the parties remained intact and are not invalidated due to the determination. Most of the Malaysian standard forms of construction contracts only carry provisions for determination of the Contractors employment by the Employer in the event of

96

2nd Quarter 2008

specified breach by the Contractor of its obligation to complete the works accordingly or conversely determination of its own employment by the Contrac tor if Employer breaches its contractual obligations as provided in the particular contract. PAM 2006 & PAM 1998 cI 25 & cl 26, IEM 1989 cl 51 & 52 and CIDB 2000 cl 44 & cl 45 provide for determination of the Contractors employment by either contracting parties except for JKR 203A cl 51 and JKR DB/T cl 54 which provide for determination of Contractors employment by the Employer only.

What is Termination of Contract?

Termination of contract occurs when a valid and enforceable contract is brought to an end either by becoming impossible to perform due to unforeseeable circumstances at the time the contract was formed or by the actions of one or both parties. Termination at common law can be done through repudiation in a narrow sense where the repudiating party refuses to perform the contract or by defective performance where a contracting partys performance is so grossly defective as to go

rticle

to the root of the contract. It takes place when the guilty party commits any repudiation, which is a breach of a fundamental term. This is a condition that the parties have expressly or impliedly agreed to be crucial so much so that its breach entitles the innocent party to discharge himself from further performance under the contract This is provided and illustrated in Section 40 of the Contracts act 1950.. The entire contract is brought to an end and parties are excused from further performance when the contract is repudiated by one party and the other party accepts the repudiation. When repudiation occurs, the innocent party can sue for damages resulting from the breach of contract. This is provided and illustrated in Section 76 of the Contracts Act 1950. However, a contract may be also terminated by exercise of express rights set out in the provision/s of the contract itself, which may have similar wordings and implications to a determination clause as provided under most of the standard forms of construction contracts. Examples of which, are Termination for Co nve n i e n ce, Te r m i n at i o n by Default or Termination without Default clauses. The Employer may terminate the contract by exercising powers expressly provided under such termination clauses. Such clauses, which often come with cer tain procedures and terms, somewhat improve the common law rights of the parties by giving specific grounds for termination which would not normally entitle one party to terminate at common l aw. N e ve r t h e l e s s i t m u s t b e appreciated that such express termination is conceptually different from the determination of the employment of the contractor in that by such termination, the rights and obligations of the parties are arguably that as if the contract has been terminated at common law even though the parties may have

prescribed the consequential express rights and obligations.

Determination of Employment under Construction Contracts

The determination of employment clauses in most of the standard forms of construction contracts set out the following basic outline: (a) Either party may determine the employment by giving notice of default. If the defaulting party fails to remedy the default within a required period, a notice of determination is issued to the defaulting party provided it is not be given unreasonably or vexatiously; (b) A list of events of default entitling a party to distinguish between remediable and nonremediable defaults; and (c) Available solutions for the nondefaulting party in the event of determination. Under most construction contracts, d e te r m i n a t i o n o f Co n t ra c to r s employment may be exercised either by the Employer or the Contractor, as described below. There is no such provision for determination of the Employers employment, as the Contractor cannot determine the Employers employment other than to determine its own employment under the contract.

the Contractor under the contract. Same or similar provisions can be found under PAM 2006 & PAM 1998 cl 25.2, JKR 203A cl 51 (a), JKR DB/T cl 54.1, IEM 1989 cl 51 (a) and CIDB 2000 cl 44.1 (a), (b) & (d). Further, in the event of the Contractors insolvenc y or bank ruptc y, the employment of the Contractor under the contracts shall be automatically determined and the notice of default is not required under PAM 2006 & PAM 1998 cl 25.3. However, under JKR 203A cl 51 (b), JKR DB/T cl 54.2 and IEM 1989 cl 51 (b), the Employer may without prejudice to any other rights, send a notice by registered post to determine the employment of the Contractor. In the case of CIDB 2000 cl 44.2, the Employer may without prejudice to any other rights or remedies, by notice, determine the employment of the Contractor under contract and the determination takes effect on the date of the receipt of notice. CIDB 2000 cl 44.1 (c) also provides for situation when the Contractor ends the Specified Default or the Employer does not give further notice to determine but the Contractor repeats the Specified Default, then the Employer may without prejudice to any other rights or remedies, by a further notice, determine the employment of the Contractor and such determination takes effect on the date of the receipt of notice. In addition, the Employer may proceed to claim for the performance security deposit (i.e. Bank Guarantee, Performance Bond, etc) against the issuing body and use the deposit to set off any direct loss and expense claim incurred by the Employer due to the Contractors default leading to determination of Contractors employment. The following Table 1 tabulates t h e E m p l oye r s ex p re s s r i g ht s to determine the Contrac tor s employment upon the Contractors

Determination of Contractors Employment by Employer under Construction Contracts

As stipulated under most construction contract provisions on determination procedures, the Architec t/P.D./ E n g i n e e r / S . O. m u s t g i v e t h e Contractor notice by registered post specifying the defaults, provided that such notice is not given unreasonably or vexatiously. If the Contractor does not attempt to remedy the defaults within 14 days after receipt of such notice, then the Employer may within a further ten days determine the employment of

97

2nd Quarter 2008

rticle

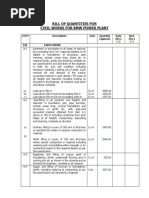

Table 1: Express Rights of the Employer to determine the Contractors Employment upon the Contractors defaults

Contractors Defaults Fails to commence Works in accordance with the Contract Fails to provide Performance Security Deposit Suspension of Works Fails to proceed regularly and diligently Fails to execute Works in accordance with the Contract Fails to remove defective work Assignment or Sub-letting without consent Abandoned the Contract Failure to comply with Architect/ P.D./Engineer/S.O.s instructions Contractors bankruptcy Cl 25.1 (e) Cl 25.1 (f) Cl 25.1 (d) Cl 25.3 Cl 25.1 (iii) Cl 25.1 (iv) Cl 25.1 (v) Cl 25.1 (vi) Cl 25.3 Cl 51 (b) (i), (ii), (iii) & (iv) Cl 54.2 (a), (b), (c) & (d) Cl 51 (b) (i), (ii), (iii) & (iv) Cl 44.1 (a) (vii) Cl 44.2 (a), (b), (c) & (d) Cl 25.1 (b) Cl 25.1 (c) Cl 25.1 (i) Cl 25.1 (ii) Cl 51 (a) (i) Cl 51 (a) (ii) Cl 51 (a) (iii) Cl 51 (a) (iv) Cl 51 (a) (v) Cl 54.1 (a) Cl 54.1 (b) Cl 54.1(c) Cl 54.1 (d) Cl 54.1 (e) Cl 51 (a) (i) Cl 51 (a) (ii) Cl 51 (a) (iii) Cl 51 (a) (iv) Cl 51 (a) (v) Cl 44.1 (a) (v) Cl 44.1 (a) (vi) PAM 2006 Cl 25.1 (a) PAM 1998 JKR 203A JKR DB/T IEM 1989 CIDB 2000 Cl 44.1 (a) (i) Cl 44.1 (a) (ii) Cl 44.1 (a) (iii) Cl 44.1 (a) (iv)

Table 2: Rights and Duties of Employer and Contractor for Determination of Contractors Employment by Employer

Brief Description of Relevant Contract Clauses The Contractor must vacate the site and remove all equipment and personnel (including his subcontractors) The Employer is entitled by himself or to employ others to complete the outstanding works The Contractor is not entitled to any monies until after completion of the outstanding works by the Employer The Contractor must assign to the Employer, contracts with his suppliers and sub-contractors upon notice by the Employer The Employer to claim expenses, loss and damages suffered. PAM 2006 25.4 (a) & (c) 25.4 (a) 25.4 (d) 25.4 (a) & (b) 25.4 (d) PAM 1998 25.4 (i) & (iii) 25.4 (i) 25.4 (iv) 25.4 (ii) JKR 203A 51 (c) (i) & (iv) 51 (c) (ii) 51 (c) (v) & (vi) 51 (c) (iii) 51 (c) (v) JKR DB/T 54.3 (a) & (d) 54.3 (b) 54.3 (e) & (f) 54.3 (c) IEM 1989 51 (c) (i) & (iv) 51 (c) (ii) 51 (c) (v) & (vi) 51 (c) (iii) 51 (c) (v) CIDB 2000 44.3 (a) & (b) 44.3 (c) 44.3 (e) & (f) 44.3 (d)

25.4 (iv)

54.3 (e)

44.3 (f)

defaults and Table 2 summarizes the rights and duties of the Employer or Contractor upon determination of the Contractors employment by Employer.

Determination of Own Employment by Contractor under Construction Contracts

As stipulated under PAM 1998 cl 26.1 and IEM 1989 cl 52 (a), the Contractor is required to issue notice by

registered post or recorded delivery to determine its own employment under contract. Under PAM 2006 cl 26.2 and CIDB 2000 cl 45.1 (b), the Contractor must give 14-days default notice to the Employer. If the Employer continues with the default, the Contractor may within ten days after the expiry of the 14 day notice by a further notice determine his own employment, provided that such notice is not given unreasonably or vexatiously.

98

2nd Quarter 2008

Fu r t h e r, i n t h e e v e n t o f t h e Employers insolvency or bankruptcy, the employment of the Contractor under the contracts is automatically determined and the notice of default is not required under PAM 2006 cl 26.3. However, under CIDB 2000 cl 45.2, the Contractor may without prejudice to any other rights or remedies by a notice determine its own employment under contract and the determination takes effect on the date of the receipt of notice.

rticle

JKR 203A and DB/T contracts do not have any provisions for the Contractor to determine its own employment. CIDB 2000 cl 45.1 (c) also provides that in the event if the Employer ends the Specified Default or the Contrac tor does not give further notice to determine but the Employer repeats the Specified Default then the Contractor may without prejudice to any other rights or remedies may by a further notice to the Employer, to determine its own employment under contract and the determination takes effect on the date of the receipt of notice. I n addition, the Contrac tor is given a right under PAM 1998 cl

26.3 to detain all unfixed goods and materials which may become the property of the Employer as security for all monies due to him. Further, the Contractor is entitled to be returned the performance security deposit furnished to the Employer, unless it has an express ter m cover ing the eventualit y of automatically lapsing upon determination of own employment by the Contractor. The following Table 3 indicates the express rights of the Contractor to determine its own employment upon the Employers default and Table 4 summarizes the rights and duties of the Employer or Contractor for determination of its own employment by the Contractor.

Termination of Contract at Common Law

The termination of contract at common law is a serious step which should be taken only after careful consideration and appropriate professional advice sought. The right to terminating a contract depends on the nature and the seriousness of the consequences of the other partys breach. The breach must either be of a fundamental term of the contract, often described as one that goes to the root of the contract, or alternatively the consequences of the breach must be such that they substantially deprive the innocent party of the entire benefit intended by the contract.

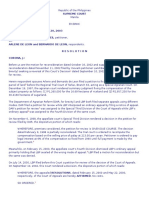

Table 3: Express Rights of the Contractor to determine its Own Employment upon the Employers defaults

Employers Defaults Failure to pay Interference with Certificates Suspension of Works Failure to appoint S.O. upon his death Employers Insolvency PAM 2006 Cl 26.1 (a) Cl 26.1 (b) Cl 26.1 (d) 26.1 (c) 26.3 PAM 1998 Cl 26.1 (i) Cl 26.1 (ii) Cl 26.1 (iv) Cl 26.1 (iii) JKR 203A JKR DB/T IEM 1989 Cl 52 (a) (i) Cl 52 (a) (ii) CI 52 (a) (iii) CIDB 2000 Cl 45.1 (a) (i) Cl 45.1 (a) (ii) Cl 45.1 (a) (iii) Cl 45.2 (a), (b), (c) & (d)

Note: JKR form of contract does not allow for the rights of the Contractor to determine his own employment upon the Employers defaults.

Table 4: Rights and Duties of Employer or Contractor for Determination of its Own Employment by Contractor

Brief Description of Relevant Contract Clauses The Contractor to cease works and vacate the site and remove all equipment and personnel (including his subcontractors) The Contractor is entitled to be paid the amount representing the value of the works done to date resulting from the determination The Contractor is entitled for loss and expense suffered by them resulting from the determination PAM 2006 26.4 (a) PAM 1998 26.2 (i) JKR 203A JKR DB/T IEM 1989 52 (b) CIDB 2000 45.3 (a)

26.4 (b)

26.2 (ii)

45.3 (b) & (c) 45.3 (b)

26.4(b)

26.2 (ii)

Note: JKR forms of building contract does not allow for the rights and duties of Employer or Contractor for Determination of Own Employment by Contractor

100

2nd Quarter 2008

rticle

The following relevant case laws discuss the typical grounds that may constitute repudiation by the Employer or Contractor, as the case may be, to cause a termination of contract at common law: (a) Failure to give possession of the site In the case of Attorney General of Singapore v Wong Wai Cheng Trading and Union Contractors (1980) - The Court of Appeal in Singapore held that a delay in site possession by a period of 30 months which was in excess of the contrac t period (24 months) itself was not a fundamental breach having regard to the express provisions in the contract that shows that the parties had clearly contemplated at the time the contract was made that hindrances and delays, including late site possession, to the execution of Works were to be allowed for. In the event of such delays, the contract expressly provides that the Contractor would be compensated. The Court came to the conclusion that there was no fundamental breach unless the continued performance by the Contractor under contract was rendered impossible or would result in something totally different from that which the contrac t contemplated. (b) Failure to Pay Haji Abu Kassim v Tegap Construction Sdn Bhd (1981) The Judges at the Court of Appeal agreed with the High Court Judges decision that the termination of the contract was bad in law and the appellant had failed to honour the architects certificate. It was found that at that relevant time, the appellant did not have the funds to make payment and used the complaint that the respondent used inferior materials in construction as a breach of agreement, which was found to be completely without merit. Lep Air Services Ltd v Rolloswin (1973) - The House of Lords held

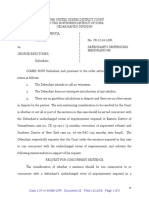

Construction work in progress

that the payment of 10,060 out of 24,000 due as payable in instalments was a breach as such, constituting a repudiation of the contract. (c) Completion made impossible by prevention or hindrance Pe m b i n a a n LC L S d n B h d v S K Styrofoam (M) Sdn Bhd (2007) This is a case where appellant wrote to the respondent that it was entitled to temporarily stop work based on physical impossibility or hindrance to doing work. The respondent terminated the contract after the appellant did not re commence work. Arbitration took place where the Arbitrator ruled that the respondents termination of the contract was invalid and consequently the respondent had acted in breach of contract. However, when the respondent challenged the Arbitrators decision, the High Court Judge held that the Arbitrator had committed errors of law and set aside the Arbitrators award. Upon appeal in the Court of Appeal, the learned Judge was convinced with the Arbitrator s findings that the respondent was in breach of contract because its notice of termination was bad at common

101

2nd Quarter 2008

law rendering the award beyond attack. The learned Judge set aside the High Court Judges orders and restored the Arbitrators award. William Cory & Son Ltd v City of London Corporation (1951) Lord Asquith held that a term is necessarily implied in any contract that neither party shall prevent the other from performing it. An Employer who without lawful excuse, by his acts of hindrance or prevention, renders impossible the completion of the Works by the Contractor could be held liable to have repudiated the contract. (d) Abandoning the Works Cheok Hock Beng v Lim Thiam Siong (1992) The owners of the land terminated the agreement with the developer on the grounds that the developer had repudiated them by failing to carry out construction works or unable to perform them. The High Court found that the plaintiffs (owners) were entitled to repudiate the agreement and an order that the possession of the land be given back to the plaintiff. Rice v Great Yarmouth Borough Council (2003) - In this case Great Yarmouth Borough Council argued

rticle

that an express termination clause should be applied literally, that the council could terminate Rices four-year employment contract as gardener for a breach of any of his obligations under the Contract by abandoning his works. However, the Court of Appeal said the idea that the clause would entitle the council to terminate a contract such as this at any time for any breach of any term flies in the face of commercial common sense. The court made clear that despite the reference to a breach of any obligation, before the contract could be terminated there had to be either a single breach serious enough to be repudiatory on its own or an accumulation of breaches that together could be described as repudiatory. The test applied was whether the council was deprived of substantially the whole benefit of what it had contracted for over a given period. It was held on facts that the test was not met and so Council was not entitled to terminate the contract which taking into account a drought during the summer and the Councils own behaviour that had contributed to Rices inability to perform of his obligations and complete his works. (e) Defective works DCMD Museum Associates v Shademaker (M) Sdn Bhd (1999) In this case, the plaintiff issued a notice of default (despatched By Hand instead of registered post) requesting the defendant to remedy all faults within 14 days failing which the plaintiff would terminate the sub-contract. The defendant refused to accept the plaintiff s repudiation of the sub-contract and an injunction was granted by the court restraining the defendant from being on the construction site. The learned Judge agreed with the plaintiff that by service to the sub-contractor informing of default includes service by hand. Moreover, the defendant had replied to the notice refusing repudiation

or termination of sub-contract and therefore, the defendant cannot claim service of notice was not carried on him. Hoenig v Issaacs (1952) - In a lump sum contract which the sum is payable on completion, the Owner cannot refuse to pay although there are small items which are not in compliance with the specification of the contract when the work is substantially completed. The Owner is obliged to make prompt payment of the contract sum less an allowance based on the cost of completing the defective work. However, even if the Contractor completes the per formance of the work in accordance with the specifications, the Owner waives the right to enforce such condition when he takes benefit of the wor k by using the apar tment and defective furniture, as such, the Owner is obliged to pay to Contractor which he had completed the works after making the above described deductions of defective works. Further, defective works during the currency of the contract would only amount to a repudiatory breach where the defects are of such magnitude that the Contractor had no hope of rectifying them. Interestingly, in the case of Malayan Flour Mills Sdn Bhd v Raja Lope & Tan Co & Anor (1998), whereby pursuant to Cl.63 of the contract for the construction, completion and maintenance of civil and building works for a boiler breeder farm, the applicant terminated the services of the respondents and the dispute went before an arbitrator, who decided that the termination was unlawful in his interim award, based upon a Tanzanian Court of Appeal case of Mvita Construction Co Ltd v Tanzania Harbours Authority(1988), which held that a party cannot resort to the common law remedy of acceptance of repudiation when they have relied upon a contractual term to exercise its power to

102

2nd Quarter 2008

excuse the other party from further performance of their obligation under the contract. In an originating motion application to the High Court, the applicant sought, apart from whether there was any misconduct on the part of the learned arbitrator, whether a party could resort to common law remedy where his rights under the contract had been exercised. It was held that Since the applicant had exercised his remedy under the contract, the applicant was bound by its terms. Accordingly, the applicant cannot resort to common law to govern the termination The honourable High Court judge, Nik Hashim J, also found that there was no misconduct on the part of the learned arbitrator as he was right in his findings and conclusions. Since the termination was bad in law, it follows that the termination is unlawful.

Conclusion

A contract can be lawfully terminated by either a contractual determination or a common law termination. In most of the standard forms of construction contracts, determination clauses are usually draf ted as provisions for determination of Contractor s employment under contract, whereby the Contractors duty or entitlement to carry out further work under contract ceases but the rights of the parties under t h e co n t r a c t a n d a t co m m o n law remain intact. A party may lawfully determine the Contractors employment by exercising powers expressly provided for in the contract, usually under determination clause, as provided in most of standard forms of construction contracts. In common law termination, it takes place when the guilty party must have committed a fundamental or repudiatory breach and innocent party must have by word or action, elected to accept the repudiation.

rticle

This process does not depend on any express contractual provisions. It is a good prudent practice to ensure that determination of employment clauses by the Employer/Contractor are included in the construction contracts to clearly and properly state the contractual rights and liabilities of the parties in the event of a contractual determination or termination before the execution of the contract to mitigate any future problems and arbitration/litigation proceedings, if the parties should need to take such drastic action. Any determination or termination must be exercised with considerable caution and care. The determining/ terminating party must demonstrate that it has elected to determine the employment or terminate the contract by communicating to the other party, usually in writing. Any determination/termination notice provisions and/or procedures must strictly comply with the terms and conditions of the contract. Notwithstanding, any party contemplating to determine or te r m i n ate, w h i c h i s a s e r i o u s action often with far reaching consequences, should only do so after due consideration and professional advice sought, prior to pursuing such drastic action w h i c h ve r y o f te n e n d s u p i n arbitration or litigation. Disputing parties should consider and attempt amicable settlement first by mutual termination, if possible. Another possible dispute resolution route is through alternative dispute resolution such as mediation, rather than to embark straight on to a long drawn and/or costly legal/ arbitration proceedings to resolve their dispute. Entrusty would like to acknowledge and thank Mr Lim Chong Fong, Partner of Messrs Azman Davidson & Co for his kind review and comments given to this article.

References/Bibliography

1. Curzon,L.B., A Dictionary of Law (2nd Edition), Pitman Publised Ltd. 2. Ir Harbans Singh, K.S., Engineering and Construction Contracts Management-Post Commencement Practice , Lexis Nexis Business Solution. 3. Robinson, N.M., Lavers, A.P., George Tan Keok Heng, Raymond Chan, Construction Law in Singapore and Malaysia (2nd Eidtion), Butterworths Asia. 4. Powell-Smith, V., Chappel, D., and Simmonds, D., A Engineering Contract Dictionary, Legal Studies and Services (Publising) Ltd. 5. Chow Kok Fong, Construction Contracts Dictionary, Thompson, Swee & Maxwell Asia. 6. Wallace, I.N.Duncan, Hudsons Building and Engineering Contracts (11th Edition), Sweet & Maxwell. 7. Smith, J., The Fundamentals of Termination, Minter Ellison Lawyer, 27 April 2007. 8. Bennett, S., From Admiralty Law to Zoning Law Find The Lawyer Thats Right For You-Contract Termination, Lexis Nexis Martinadale Lawyers. 9. Noonan, P., Kennedy, S., Tips and Traps : Terminating a Contract, World Services Group, 5 May 2006. 10. Termination of Contract, Contract Journal Article, 6 June 2007. 11. Ong Hock Tek, Ho Kin Wing, Module 12, Determination and Dispute Resolution - Practical Construction Contract Adminstration/Management Training Programme, Entrusty Management Sdn. Bhd., 6 Sep 2003.

In the next issue of the MBAM journal the article will answer the question on Is Determination Of Employment And Termination Of Contract The Same In Meaning And Implications?

The Entrusty Group includes Entrusty Consultancy Sdn Bhd (formerly known as J.D. Kingsfield (M) Sdn Bhd) , BK Burns & Ong Sdn Bhd (a member of the Asia wide group BK Asia Pacific) , Pro-Value Management, Proforce Management Services Sdn Bhd / Agensi Pekerjaan Proforce Sdn Bhd and International Master Trainers Sdn Bhd. providing project, commercial and contractual management services, risk, resources, quality and value management, recruitment consultancy services and corporate training programmes to various industries, particularly in construction and petrochemical, both locally and internationally. For further details, please visit website: www.entrusty.com. or contact HT Ong at 22-1& 2 Jalan 2/109E, Desa Business Park, Taman Desa, 58100 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Tel: 6(03)-7982 2123 Fax: 6(03)-7982 3122 Email: enquiry@entrusty.com.my. Entrusty Group provides 30 minutes of free consultancy (with prior appointment) to MBAM members on their contractual questions. The Group also provides both in-house and public seminars/workshops in its various areas of expertise.

103

2nd Quarter 2008

You might also like

- Time at LargeDocument8 pagesTime at LargedanijulianaNo ratings yet

- Flow Chart From CPC To DLP To CMGDDocument4 pagesFlow Chart From CPC To DLP To CMGDSky SawNo ratings yet

- Contractor Obligations During Defects Liability PeriodDocument4 pagesContractor Obligations During Defects Liability PeriodHOONG123No ratings yet

- Comparison Between PAM1998 and PAM 2006Document31 pagesComparison Between PAM1998 and PAM 2006meishann67% (9)

- Must The Contractor Submit His Interim Payment Claims Before The Superintending Officer Certifies For Payment?Document8 pagesMust The Contractor Submit His Interim Payment Claims Before The Superintending Officer Certifies For Payment?downloademail100% (1)

- Mitsui Construction Co LTD V Attorney-GeneraDocument34 pagesMitsui Construction Co LTD V Attorney-GeneraMazuan LinNo ratings yet

- Different Between PAM 2006 and PWD 203Document2 pagesDifferent Between PAM 2006 and PWD 203Bgee Lee0% (2)

- Differences Between JKR/PWD and PAM Contract FormsDocument2 pagesDifferences Between JKR/PWD and PAM Contract FormsMohd Fazri Idris100% (4)

- Pam 2006Document154 pagesPam 2006Max Awal100% (1)

- Loss and Expense Claims in Practice PDFDocument32 pagesLoss and Expense Claims in Practice PDFAbd Aziz MohamedNo ratings yet

- PWD 203aDocument12 pagesPWD 203aGary Brandon100% (1)

- Comparison Between PWD Form 203A and PWD Form Design and BuiltDocument16 pagesComparison Between PWD Form 203A and PWD Form Design and BuiltMeor Syahmi100% (6)

- Full Report of Extension of Time For Professional Practise IiDocument59 pagesFull Report of Extension of Time For Professional Practise IizhdhishakNo ratings yet

- CIDB Law Report 2015Document344 pagesCIDB Law Report 2015Weei Zhee70No ratings yet

- PAM2016 Vs PAM2018Document30 pagesPAM2016 Vs PAM2018Afiq Zuhairy100% (2)

- JKR Design and Build ConditionDocument14 pagesJKR Design and Build Conditionjerrycl67% (3)

- EOTDocument17 pagesEOTCherishGlory100% (2)

- Pam Guide Book Form 2006 EOTDocument17 pagesPam Guide Book Form 2006 EOTar_mohamad100% (1)

- SBEQ2413 - Completion of WorksDocument38 pagesSBEQ2413 - Completion of WorksHana AmriNo ratings yet

- 17.defect Liability Period and Account Closing - en .Wan SaipallahDocument34 pages17.defect Liability Period and Account Closing - en .Wan SaipallaherickyfmNo ratings yet

- Extension of Time and Liquidated DamagesDocument19 pagesExtension of Time and Liquidated DamagesWan Hakim Wan YaacobNo ratings yet

- PWD Form 203aDocument2 pagesPWD Form 203aZhao Ying100% (2)

- Nominated Sub Contractor & Supplier PDFDocument20 pagesNominated Sub Contractor & Supplier PDFnurhanis nadhirah binti ramli100% (2)

- Certificate of Practical CompletionDocument1 pageCertificate of Practical CompletionMohd Asrul Abu Harirah100% (1)

- BEM 1.2003 Guidelines For Checking The Work of Another EngineerDocument11 pagesBEM 1.2003 Guidelines For Checking The Work of Another EngineerVong Kee SinNo ratings yet

- Pam 2006 Diagramatic Contract ImplimentationDocument47 pagesPam 2006 Diagramatic Contract ImplimentationCastiel Arumugam100% (1)

- Similarities of Standard Forms of Contract in MalaysiaDocument5 pagesSimilarities of Standard Forms of Contract in MalaysiaZinck Hansen88% (8)

- Contractors Right of Action For Late or Non Payment by The EmployerADocument31 pagesContractors Right of Action For Late or Non Payment by The EmployerArokiahhassan100% (1)

- PWD Form DB (2007)Document67 pagesPWD Form DB (2007)erickyfmNo ratings yet

- Comparison On PAM Contract 2006 & 2018 - Group 1Document22 pagesComparison On PAM Contract 2006 & 2018 - Group 1Prabu Alagappen86% (7)

- Differences Between PWD and PAM Tender DocumentsDocument2 pagesDifferences Between PWD and PAM Tender DocumentsHafizah Ezani78% (9)

- Is CCC The Only Contractual Requirement For The Delivery of VP in A Sales and Purchase AgreementDocument3 pagesIs CCC The Only Contractual Requirement For The Delivery of VP in A Sales and Purchase AgreementRidha Razak100% (2)

- SKS Pavillion SDN BHD V Tasoon Injection Pile SDN BHDDocument21 pagesSKS Pavillion SDN BHD V Tasoon Injection Pile SDN BHDHanani HadiNo ratings yet

- Research On Preparing Eot Application, Analyzing and Certification by Ar Ridha RazakDocument40 pagesResearch On Preparing Eot Application, Analyzing and Certification by Ar Ridha RazakRidha Razak100% (3)

- JKR - Conditions of ContractDocument56 pagesJKR - Conditions of Contractezarul fitri100% (4)

- PAM Contract 2018 Major ChangesDocument1 pagePAM Contract 2018 Major ChangesLee Yin Ling100% (1)

- Adjustment of Contract & Final Accounts AsimentsDocument23 pagesAdjustment of Contract & Final Accounts Asimentsrubbydean100% (9)

- The PAM 2006 Standard Form PDFDocument969 pagesThe PAM 2006 Standard Form PDFVon Jin100% (3)

- PWD 203 ADocument9 pagesPWD 203 ASufiah Dina100% (2)

- Loss ExpenseDocument10 pagesLoss ExpensefuzahjamilNo ratings yet

- Slides - EOT & Delay AnalysisDocument114 pagesSlides - EOT & Delay AnalysisHafizah AyobNo ratings yet

- Comparing PAM and CIDB Standard Forms of Building Contracts in MalaysiaDocument21 pagesComparing PAM and CIDB Standard Forms of Building Contracts in Malaysiateeyuan100% (6)

- CIDB Contract PDFDocument36 pagesCIDB Contract PDFKhay SaadNo ratings yet

- Sample Loss and Expense ClaimDocument2 pagesSample Loss and Expense ClaimIfeanyi Obieje50% (8)

- Sub-Clause 3.5 - Notice of Agreement-DeterminationDocument3 pagesSub-Clause 3.5 - Notice of Agreement-Determinationkhiem44100% (1)

- JKR - LumpSum 2013 PDFDocument50 pagesJKR - LumpSum 2013 PDFKhairul IzhamNo ratings yet

- Guide To L&E Application by Contractor in Accordance To PAM 2006Document19 pagesGuide To L&E Application by Contractor in Accordance To PAM 2006Ridha Razak100% (4)

- Assignment 1Document17 pagesAssignment 1Ko Ka KunNo ratings yet

- Comparison Standard Form Nazib FaizalDocument9 pagesComparison Standard Form Nazib FaizalTan Chi SianNo ratings yet

- Design, Construction, Testing and Commissioning Tender DocumentsDocument34 pagesDesign, Construction, Testing and Commissioning Tender DocumentsOceanv100% (1)

- Professional Practice (Contract Managment)Document37 pagesProfessional Practice (Contract Managment)JingYi100% (2)

- Ref - Determination PDFDocument7 pagesRef - Determination PDFpeoplessmile2000No ratings yet

- Unilaterally Termination For ConvenienceDocument11 pagesUnilaterally Termination For ConvenienceZinck HansenNo ratings yet

- Topic 01 Suspension and Termination 2014Document15 pagesTopic 01 Suspension and Termination 2014Kaps RamburnNo ratings yet

- Defects Liability After The Contract Has Been Terminated by The ContractorDocument11 pagesDefects Liability After The Contract Has Been Terminated by The ContractoraberraNo ratings yet

- Loss and Expense ClaimsDocument28 pagesLoss and Expense ClaimsJama 'Figo' MustafaNo ratings yet

- FIDIC: Termination by The Employer Under The Red and Yellow BooksDocument8 pagesFIDIC: Termination by The Employer Under The Red and Yellow BookssaihereNo ratings yet

- Termination and Suspension of Construction ContractsDocument5 pagesTermination and Suspension of Construction ContractsWilliam TongNo ratings yet

- Advanced Construction Law - Q2Document4 pagesAdvanced Construction Law - Q2Neville OkumuNo ratings yet

- Negotiation of Construction ClaimsDocument27 pagesNegotiation of Construction ClaimsGiora Rozmarin100% (3)

- Public Speaking Tips: 35 Public Speaking Tools For Great SpeakingDocument42 pagesPublic Speaking Tips: 35 Public Speaking Tools For Great SpeakingAkash Karia100% (2)

- Civil Bill of QuantitiesDocument49 pagesCivil Bill of QuantitiesSudu Banda100% (1)

- Amount in Figures in Words 1.00 Bill No: 1 Site Clearance Unit Rate Item No. Description Unit Estimated QtyDocument22 pagesAmount in Figures in Words 1.00 Bill No: 1 Site Clearance Unit Rate Item No. Description Unit Estimated QtySubrahmanya SarmaNo ratings yet

- A Legal AnalysisRuzian MarkomDocument18 pagesA Legal AnalysisRuzian MarkommrlobboNo ratings yet

- d5 - Preparation of A Layout PlanDocument32 pagesd5 - Preparation of A Layout PlanmrlobboNo ratings yet

- Bill of QuantitiesDocument10 pagesBill of Quantitieskresimir.mikoc9765100% (1)

- House Tender BoQDocument149 pagesHouse Tender BoQJhonny SarmentoNo ratings yet

- Steel Frame Vs Concrete Frame For High Rise BuildingsDocument6 pagesSteel Frame Vs Concrete Frame For High Rise BuildingsdhawanaxitNo ratings yet

- Buildcost Construction Cost Guide 1st Half 2012Document8 pagesBuildcost Construction Cost Guide 1st Half 2012mrlobboNo ratings yet

- Construction Cost Comparison Between Conventional and Formwork SystemsDocument7 pagesConstruction Cost Comparison Between Conventional and Formwork SystemsmrlobboNo ratings yet

- Urban DrainageDocument98 pagesUrban DrainagemrlobboNo ratings yet

- The Asean Tax System Bangkok ThailandDocument22 pagesThe Asean Tax System Bangkok ThailandAaron BrookeNo ratings yet

- MS Project TutorialDocument70 pagesMS Project TutorialViral Soni100% (14)

- Nick Gould - Adjudication in MalaysiaDocument4 pagesNick Gould - Adjudication in MalaysiamrlobboNo ratings yet

- Bandarserialamcityofknowledge 130916213932 Phpapp01Document22 pagesBandarserialamcityofknowledge 130916213932 Phpapp01mrlobboNo ratings yet

- Construction Cost Comparison Between Conventional and Formwork SystemsDocument7 pagesConstruction Cost Comparison Between Conventional and Formwork SystemsmrlobboNo ratings yet

- Any Level Method 12-15-05Document8 pagesAny Level Method 12-15-05mrlobboNo ratings yet

- Sustainable Development in The Building Sector Green Building Framework in MalaysiaDocument8 pagesSustainable Development in The Building Sector Green Building Framework in MalaysiaEdzudy ZaibidinNo ratings yet

- Steel Frame Vs Concrete Frame For High Rise BuildingsDocument6 pagesSteel Frame Vs Concrete Frame For High Rise BuildingsdhawanaxitNo ratings yet

- 1.D Project Proposal ReportDocument0 pages1.D Project Proposal ReportmrlobboNo ratings yet

- Building Planning and MassingDocument114 pagesBuilding Planning and MassingVineet VermaNo ratings yet

- Measurement of Building AreasDocument0 pagesMeasurement of Building AreasmrlobboNo ratings yet

- Brief Comparison Between Meditation, Adjudication, Arbitration and Litigation - ADRDocument2 pagesBrief Comparison Between Meditation, Adjudication, Arbitration and Litigation - ADRmrlobboNo ratings yet

- Accounting ValuationDocument59 pagesAccounting ValuationMarian Covlea100% (2)

- FLUID MECHANICS EXPLAINEDDocument29 pagesFLUID MECHANICS EXPLAINEDpwanjotsinghNo ratings yet

- Construction HandbookDocument480 pagesConstruction Handbooksmacfarlane1463089% (27)

- Steel Frame Vs Concrete Frame For High Rise BuildingsDocument6 pagesSteel Frame Vs Concrete Frame For High Rise BuildingsdhawanaxitNo ratings yet

- IndexDocument105 pagesIndexJo YabotNo ratings yet

- Steel Estimating TodayDocument9 pagesSteel Estimating Todayntah84100% (2)

- Companies Act 1965 SummaryDocument50 pagesCompanies Act 1965 SummaryKamsul DiksiNo ratings yet

- Froilan Vs PAN Oriental ShippingDocument6 pagesFroilan Vs PAN Oriental ShippingRelmie TaasanNo ratings yet

- Ang Yu Asuncion Vs CADocument2 pagesAng Yu Asuncion Vs CAAnonymous gHx4tm9qmNo ratings yet

- Anime d20 SRD v1.0 - Chap01Document3 pagesAnime d20 SRD v1.0 - Chap01Rémy TrepanierNo ratings yet

- Union-University dispute over CBA interpretation and grievance proceduresDocument1 pageUnion-University dispute over CBA interpretation and grievance proceduresJulius Geoffrey TangonanNo ratings yet

- HK SFC Case Against Moody's For Red Flag ReportDocument7 pagesHK SFC Case Against Moody's For Red Flag ReportrowerburnNo ratings yet

- United States v. Charles Ray Gregory, 977 F.2d 596, 10th Cir. (1992)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Charles Ray Gregory, 977 F.2d 596, 10th Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Federalisms of US and IndiaDocument3 pagesFederalisms of US and IndiaTanya TandonNo ratings yet

- Uniland Resources V DBP, GR No. 95909, Aug. 16, 1991Document5 pagesUniland Resources V DBP, GR No. 95909, Aug. 16, 1991Justine UyNo ratings yet

- George Bing Tonks Sentencing Memo, 2008 Northern IowaDocument5 pagesGeorge Bing Tonks Sentencing Memo, 2008 Northern IowaJeff ReinitzNo ratings yet

- 324duty of One Who Takes Charge of Another Who Is Helpless - WestlawNextDocument4 pages324duty of One Who Takes Charge of Another Who Is Helpless - WestlawNextjohnsmith37788No ratings yet

- United States v. Phillips, 4th Cir. (2001)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Phillips, 4th Cir. (2001)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Agrarian CasesDocument26 pagesAgrarian CasesKliehm NietzscheNo ratings yet

- Trade Union ActDocument23 pagesTrade Union ActAditya Kulkarni100% (1)

- Raghavendra Letter To Judge Hon. PitmanDocument10 pagesRaghavendra Letter To Judge Hon. PitmanIvyGateNo ratings yet

- ITunes Privacy October DismissalDocument10 pagesITunes Privacy October DismissalMikey CampbellNo ratings yet

- Family LawDocument10 pagesFamily LawAiman Kulsoom RizviNo ratings yet

- ICAR Statement To EUDocument3 pagesICAR Statement To EUaccountabilityrdtbleNo ratings yet

- Palana v. PeopleDocument2 pagesPalana v. PeopleRafaelNo ratings yet

- General Counsel Corporate Secretary in Chicago IL Resume Koreen RyanDocument5 pagesGeneral Counsel Corporate Secretary in Chicago IL Resume Koreen RyanKoreenRyanNo ratings yet

- Pandey v. Freedman, 66 F.3d 306, 1st Cir. (1995)Document6 pagesPandey v. Freedman, 66 F.3d 306, 1st Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Loyola Grand Villas Homeowners (South) Association Inc. vs. CADocument1 pageLoyola Grand Villas Homeowners (South) Association Inc. vs. CAArmand Patiño AlforqueNo ratings yet

- Fruit of The Loom VDocument2 pagesFruit of The Loom VBadette Lou R. Katigbak - LasinNo ratings yet

- Austin Sarat-A World Without Privacy - What Law Can and Should Do - Cambridge University Press (2015)Document290 pagesAustin Sarat-A World Without Privacy - What Law Can and Should Do - Cambridge University Press (2015)Profesor UmNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument44 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- SSC Online Coaching CGL Tier 1 GK Indian Polity 140214010607 Phpapp01Document7 pagesSSC Online Coaching CGL Tier 1 GK Indian Polity 140214010607 Phpapp01shekhar.mnnitNo ratings yet

- Balbastro vs. Court of AppealsDocument5 pagesBalbastro vs. Court of AppealsRomy Ian LimNo ratings yet

- A Guide to Recording Your Own Court HearingDocument150 pagesA Guide to Recording Your Own Court HearingElen VilshunNo ratings yet

- 18 Callado Vs Irri 244 Scra 210Document4 pages18 Callado Vs Irri 244 Scra 210Armand Patiño AlforqueNo ratings yet

- Alan Presbury v. Michael Wenerowicz, 3rd Cir. (2012)Document4 pagesAlan Presbury v. Michael Wenerowicz, 3rd Cir. (2012)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Domingo vs. Singson, 822 SCRA 401, April 05, 2017Document14 pagesDomingo vs. Singson, 822 SCRA 401, April 05, 2017j0d3No ratings yet