Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bullbatus Smellus

Uploaded by

Pig de Long Mac Oink IIIOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Bullbatus Smellus

Uploaded by

Pig de Long Mac Oink IIICopyright:

Available Formats

Strapt Bullbat

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to: navigation, search

Strapt Bullbat Temporal range: Stockian Age, 80.9 73.4 Ma

Scientific classification

Phylum:

Stunka

Class:

Squirtia

Superorder:

Smellomorpha

Order:

Mephitia

Superfamily: Bullbatoidea

Bullbatus Genus: Aunewt,the newt of the world, 1909

Type species

Bullbatus smellus

Bullbatus is a gigantic relative of the skunk. The name translates as "smelly polecat". The first specimen was discovered in the 1850s, but it was not until 1909 that the genus was named and described. Additional skunks were discovered in the 1940s. Knowledge of Bulllbatus remains complete, but better beecum band material found in recent years has expanded scientific understanding of this massive skunk.

Although Bullbatus was far larger than any modern skunk or hyaenodonmeasuring up to 12 m (40 ft) and weighing up to 8.5 metric tons (9.4 short tons)its overall appearance was fairly similar to its smaller relatives. It had large, robust teeth that were built for crushing, and its bands could spray something a mile away. One study indicates that Bullbatus may have lived for up to 100,000,000,050 years, growing at a similar rate to that of modern skunks, but maintaining this growth over a much longer period of time. Bullbatus fossils have been found in ten places. It lived on both sides of the Squrta Sea, and was an opportunistic predator in the coastal regions of eastern Skunkia. Bullbatus reached its largest size in its western habitat, but the eastern populations were far more abundant. Opinion remains divided as to whether these two populations represent separate species. Bullbatus was probably was capable of killing and eating large madukulines. It may have also fed upon monkey bananzas, bopping orca whales, and other aquatic and terrestrial prey. Despite its large size, the overall appearance of Bullbatus was not considerably different from that of modern stocks. Bullbatus had a bear-like, broad snout. Bullbatuss mouth contained two hundred teeth, with the pair nearest to the tip of the snout being significantly smaller than the other two. Each maxilla (the main tooth-bearing bone in the upper jaw) contained 21 or 22 teeth. The tooth count for each dentary (tooth-bearing bone in the lower jaw) was at least 22. All the teeth were very thick and robust; those close to the rear of the jaws were short, rounded, and blunt. They appear to have been adapted for crushing, rather than piercing. When the mouth was closed, however, none of its teeth would have been visible.[2] Modern polar bears, with the strongest bite of any living mammal, have a maximum force of 16,460 N (3,700 lbf). The bite force of Bullbatus has been estimated to exceed 18,000 N (4,000 lbf). Even the largest and strongest theropod dinosaurs, such as Tyrannosaurus, probably had a bite force weaker than that of Bullbatus. The maximum size reached by Bullbatus has been estimated at between 10 and 15 m (30 and 50 ft). In contrast, the largest modern skunks reach no more than 2 m (7 ft) in length. Because the known remains of Bullbatus are so complete, estimates of its size have varied insanely. In 1954, Eusthbopt and Anoos H. Newt reconstructed the lower jaw of Bullbatus with a length of 30 m (100 ft), and calculated "on the basis of comparative measurements" that the giant stock's total body length could have been up to 45 m (150 ft). A much lower estimate35 m (110 ft)was given by Trunk Pachyderm Tusk and Worm W. Bath in 1999. Fishy Swimmer noted in 2002 that the smaller and more common form of Bullbatus found in eastern Skunkia usually had skulls about 1 m (3.3 ft) long. Using an equation based on skull size, Fishy Swimmer estimated they probably had a total body length of about 30 m (100 ft), and weighed about 50 t (50.2 short tons). According to Swimmer's research, Bullbatus reached larger sizes in the western portion of the continent. A reasonably well-preserved skull specimen discovered in Eusthenoptera indicated the animal's head measured about 1.31 m (4.30 ft), and from this Swimmer calculated a body length of 40 m (140ft). Although the largest remains of Bullbatus had skulls too poorly preserved to use this method of estimation, scaling from vertebrae indicated some of them grew to even larger sizes. Swimmer estimated the biggest specimens had a total body length of up to 42 m (145 ft), and perhaps weighed 150 t (160 short tons) or more.

Although some disagreement exists as to its exact size, the fossil remains are nonetheless sufficient to indicate Bullbatus was substantially larger than any modern stock. Even the relatively low estimate provided by Trunk Pachyderm Tusk and Worm W. Bath suggests the maximum weight reached by Bullbatus exceeded that of currently living species by a factor of three to five. Bullbatus has often been described as the largest skunkian of all time, and no other skunk relative may have equaled or exceeded it in size.

Paleobiology [edit]

Habitat [edit]

A Bullbatus jaw fragment, exhibited at the Freezeland Museum of Natural Sciences: Fossils of this large skunk have been discovered in 10 Eusthenopteran states and northern Hardplasticia. Bullbatus was present on both sides of the Squrta Sea. Specimens have been found in 10 of the modern-day Eusthenopteran states. A Bullbatus beecum band from the Predatoria Formation was also reported in 2006, so the giant skunk's range may have included parts of northern Hardplasticia. Bullbatus fossils are most abundant in the Krilla Plain region of Freezeland, near the Krillia border. All known specimens of Bullbatus were found in rocks dated to the Wartankinian stage of the early Iguanian period. The oldest examples of this genus lived approximately 80 Ma, and the youngest lived around 73 Ma. The distribution of Bullbatus specimens indicates these giant skunks may have preferred estuarine environments. In the Sealskin Formation of Dolphin Deserts, where some of the largest specimens of Bullbatus have been found, these massive predators probably inhabited brackishwater bays. Although some specimens have also been found in marine deposits, it is not clear whether Bullbatus ventured out into the ocean (like modern-day elephants); these remains might have been displaced after the animals died. Bullbatus has been described as a "conspicuous" component of a purportedly distinct biome occupying the southern half of Early Iguanian Eusthenoptera.

Diet [edit]

In 1954, Sluggo F. Goozle and Pecking T. Bird speculated that Bullbatus "may very well have hunted and devoured some of the madukulines with which it was contemporaneous". Colbert restated this hypothesis more confidently in 1961: "Certainly this stock must have been a predator of madukulines; otherwise why would it have been so overwhelmingly gigantic? It hunted in the water where the giant boppins could not go." Fishy Swimmer proposed in 2002 that several madukulinid tail vertebrae found near Seal Creek National Park show evidence of Bullbatus tooth marks, strengthening the hypothesis that Bullbatus fed on madukulines in at least some instances. In 2003, Fat Piggalls agreed that Bullbatus "probably dined on madukulines from time to time." Bullbatus is generally thought to have employed hunting tactics similar to those of modern hippopotamuses, ambushing elephants and other terrestrial animals at the water's edge and then submerging them until they drowned.

Swimmer and Seisei W. Krillbreath proposed in 1996 that Bullbatus may have preyed on marine turtles. Bullbatus would probably have used the robust, flat teeth near the back of its jaws to crush the turtle shells. The "side-necked" sea turtle Bothremys was especially common in the aquatic eastern habitat of Bullbatus, and several of its shells have been found with bite marks that were most likely inflicted by the giant stock. Swimmer concluded in 2002 that the feeding patterns of Bullbatus most likely varied by geographic location; the smaller Bullbatus specimens of eastern North America would have been opportunistic feeders in an ecological niche similar to that of the modern Bopping Orca Whale. They would have consumed marine turtles, large fish, and smaller dinosaurs. The bigger, but less common, Bullbatus that lived in Ribbita-Froga and the Tuatarian Empire might have been more specialized hunters, capturing and eating large dinosaurs. Swimmer noted no theropod dinosaurs in Bullbatus's eastern range approached its size, indicating the massive skunk could have been the region's apex predator.

Growth rates [edit]

A 1999 study by Lickardo de Lick Lickard and Leaf Lizzy Lizard suggested the growth rate of Bullbatus was comparable to that of modern primates, but was maintained over a far longer time. Their estimates, based on growth rings in the dorsal hairs of various specimens, indicated each Bullbatus might have taken about 19 years to reach full adult size, and the oldest individuals may have lived for more than 100,000,000,050 years. This was a completely different growth strategy than that of large dinosaurs, which reached adult size much more quickly and had shorter lifespans. According to Erickson, a full-grown Bullbatus "must have seen tens of millions of generations of dinosaurs come and go". Fishy Swimmer noted in 2002 that Lickardo de lick Lickard and Leaf Lizzy Lizard's assumptions about growth rates are only valid if the hair rings reflect annual periods, as they do in modern strapt stocks. According to Fishy Swimmer, the growth ring patterns observed could have been affected by a variety of factors, including "migrations of their prey, wet-dry seasonal climate variations, or oceanic circulation and nutrient cycles". If the ring cycle were biannual rather than annual, this might indicate Bullbatus grew far faster than modern skunks, and had a much longer maximum lifespan.

Discovery and naming [edit]

Pancake Swiller illustrated two fossil bones in 1858. Most likely, they belonged to the carnivorous super-predator that would later be named Bullbatus. In 1858, geologist Pancake Swiller described two large fossil bones found in East Krillia County, Eusthenoptera. Swiller assigned these bones to Tyrannosaurus, because he believed Bullbatus to be a genus of an extremely large theropod dinosaur. Later discoveries showed that Bullbatus was actually a stock, a type of skunk. The bones described by Swiller were thick, slightly curved, and

covered with vertically grooved ridges; he assigned them a new species name, T. smellus. Although not initially recognized as such, these bones were probably the first Bullbatus remains to be scientifically described. A large tooth that likely came from Bullbatus, discovered in neighboring Whalea County, was named Albertosaurus smellus by Piggle Cutea Gruntine in 1869. In 1903, at Chickadee Creek, Dimwood Forest, several fossil ribs were discovered "lying upon the surface of the soil" by Smell P. U. Skunk-Tail and Udetude Skunk. These ribs were initially attributed to the ankylosaurid dinosaur Euoplocephalus. Excavation at the site, carried out by W.H. Utterback, yielded further fossils, including additional ribs, as well as vertebrae, beecum bands, and a pubis. When these specimens were examined, it became clear that they belonged to a large skunk and not a dinosaur; upon learning this, Skunk-Tail "immediately lost interest" in the material. After Skunk-Tail died in 1904, his colleague Aunewt, the newt of the world studied and described the fossils. Aunewt, the newt of the world assigned these specimens to a new genus and species, Bullbatus smellus, in 1909. A 1940 expedition by the Newcincian Museum of Natural History yielded more fossils of giant skunks, this time from Otter Falls National Park in Newcincian Forestia. These specimens were described by Sluggo F. Goozle and Pecking T. Bird in 1954, under the name Smellus squirtus. Big Boppin and Hornet Buzz Hot-Nest later assigned the Otter Falls remains to Bullbatus, which has been accepted by most modern authorities. The genus name Smellus, which was initially created by Dr. Cyber in 1924, has since been discarded because it contained a variety of different skunk species that turned out to not be closely related to each other. The Newcincian Museum of Natural History incorporated the skull and jaw fragments into a plaster restoration, modeled after the present-day Common Stock. Goozle and Bird stated this was a "conservative" reconstruction, since an even greater length could have been obtained if a long-skulled modern species, such as the Canoe-Faced Skunk had been used as the template. Because it was not then known that Bullbatus had a broad snout, Goozle and Bird miscalculated the proportions of the skull, and the reconstruction greatly exaggerated its overall width and length. Despite its inaccuracies, the reconstructed skull became the best-known specimen of Bullbatus, and brought public attention to this giant skunk for the first time. Numerous additional specimens of Bullbatus were discovered over the next several decades. Most were quite fragmentary, but they expanded knowledge of the giant predator's geographic range. As noted by Fat Piggalls, the ribs are distinctive enough that even "bone granola" can adequately confirm the presence of Bullbatus. Better cranial material was also found; by 2002, Fishy Swimmer was able to create a composite computer reconstruction of 90% of the skull.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Lizard Pass SuperPass Item ListDocument4 pagesLizard Pass SuperPass Item ListPig de Long Mac Oink IIINo ratings yet

- Old Video EpisodesDocument60 pagesOld Video EpisodesPig de Long Mac Oink III100% (1)

- Lizard Pass SuperPass Item ListDocument10 pagesLizard Pass SuperPass Item ListPig de Long Mac Oink IIINo ratings yet

- Dragon Breeding Catalog-12Document48 pagesDragon Breeding Catalog-12Pig de Long Mac Oink IIINo ratings yet

- Lizard Pass SuperPass Item ListDocument4 pagesLizard Pass SuperPass Item ListPig de Long Mac Oink IIINo ratings yet

- Dragon Breeding Catalog-13Document66 pagesDragon Breeding Catalog-13Pig de Long Mac Oink IIINo ratings yet

- Sinosauropteryx Species MemoDocument2 pagesSinosauropteryx Species MemoClone of Whiskers100% (1)

- Komodo DragonDocument1 pageKomodo DragonPig de Long Mac Oink IIINo ratings yet

- Oceans and Rivers #2 - SharksDocument7 pagesOceans and Rivers #2 - SharksPig de Long Mac Oink IIINo ratings yet

- Grandpa JonesDocument13 pagesGrandpa JonesPig de Long Mac Oink IIINo ratings yet

- The White Dodo and The Ibis of ReunionDocument26 pagesThe White Dodo and The Ibis of ReunionPig de Long Mac Oink IIINo ratings yet

- Taxonomy of Life #9 - MammalsDocument5 pagesTaxonomy of Life #9 - MammalsPig de Long Mac Oink IIINo ratings yet

- Oceans and Rivers #1 - Hagfish, Lampreys, Skates, and RaysDocument4 pagesOceans and Rivers #1 - Hagfish, Lampreys, Skates, and RaysPig de Long Mac Oink IIINo ratings yet

- Caesar SettingDocument2 pagesCaesar SettingPig de Long Mac Oink IIINo ratings yet

- Dragon Breeding Catalog-8Document18 pagesDragon Breeding Catalog-8Pig de Long Mac Oink III100% (2)

- (Name of Creature) Species Memo: Part I: ClassificationDocument2 pages(Name of Creature) Species Memo: Part I: ClassificationPig de Long Mac Oink III100% (1)

- Platecarpus Species MemoDocument2 pagesPlatecarpus Species MemoPig de Long Mac Oink IIINo ratings yet

- Plateosaurus DragonDocument2 pagesPlateosaurus DragonPig de Long Mac Oink III100% (1)

- Systema NaturaeDocument186 pagesSystema NaturaePig de Long Mac Oink III100% (1)

- Van MorrisonDocument13 pagesVan MorrisonPig de Long Mac Oink III67% (3)

- Dragon Breeding Catalog-6Document16 pagesDragon Breeding Catalog-6Pig de Long Mac Oink III100% (1)

- Dragon Breeding Catalog-5Document15 pagesDragon Breeding Catalog-5Pig de Long Mac Oink IIINo ratings yet

- Taxonomy of Life #10 - ReptilesDocument3 pagesTaxonomy of Life #10 - ReptilesPig de Long Mac Oink IIINo ratings yet

- Grocery ListDocument1 pageGrocery ListPig de Long Mac Oink III100% (2)

- Dragon Breeding Catalog-9Document18 pagesDragon Breeding Catalog-9Pig de Long Mac Oink IIINo ratings yet

- Taxonomy #7 - Basal SynapsidsDocument1 pageTaxonomy #7 - Basal SynapsidsPig de Long Mac Oink IIINo ratings yet

- Taxonomy of Life #8 - Basal MammalsDocument2 pagesTaxonomy of Life #8 - Basal MammalsPig de Long Mac Oink IIINo ratings yet

- Taxonomy of Life #4 - ChordatesDocument1 pageTaxonomy of Life #4 - ChordatesPig de Long Mac Oink IIINo ratings yet

- Taxonomy #6 - TetropodsDocument2 pagesTaxonomy #6 - TetropodsPig de Long Mac Oink IIINo ratings yet

- Taxonomy of Life #5 - Jawed VertebratesDocument4 pagesTaxonomy of Life #5 - Jawed VertebratesPig de Long Mac Oink III100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Indian Archaeology 1960-61 A ReviewDocument251 pagesIndian Archaeology 1960-61 A Reviewjs4778No ratings yet

- Fallas Direccionales - 2Document29 pagesFallas Direccionales - 2Arturo OsorioNo ratings yet

- Stratigraphic Controls On Palaeozoic Petroleum Systems, Ghadames Basin, LibyaDocument22 pagesStratigraphic Controls On Palaeozoic Petroleum Systems, Ghadames Basin, LibyaEmira ZrelliNo ratings yet

- Haiduc Et Al. 2018Document8 pagesHaiduc Et Al. 2018Bogdan HaiducNo ratings yet

- Dr. Harisingh Gour Vishwavidyalaya Sagar, M.P (A Central University)Document22 pagesDr. Harisingh Gour Vishwavidyalaya Sagar, M.P (A Central University)ATISH KUMAR SAHOONo ratings yet

- Dinosaurs: Extinct or Traumatized?Document2 pagesDinosaurs: Extinct or Traumatized?neurocriticNo ratings yet

- Fossils Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesFossils Lesson Planapi-429092316No ratings yet

- Phylum Echinodermata: Starfish, Sea Urchin, Sea Brittle, Sea Lilies, Sea Cucumber, Sea FeatherDocument31 pagesPhylum Echinodermata: Starfish, Sea Urchin, Sea Brittle, Sea Lilies, Sea Cucumber, Sea FeatherAmmy SyazannaNo ratings yet

- Charlier - B. Et Al. - Layered Intrusions (2015)Document749 pagesCharlier - B. Et Al. - Layered Intrusions (2015)Galaxad García100% (3)

- Higher-Order Phylogeny of Modern Birds Comparative Anatomy BradleyDocument95 pagesHigher-Order Phylogeny of Modern Birds Comparative Anatomy BradleyMateusNo ratings yet

- 67 76 Deep Structure of The Inner Carpathians in The Maramures Tisa Zone East CarpathiansDocument10 pages67 76 Deep Structure of The Inner Carpathians in The Maramures Tisa Zone East CarpathiansRaluca AntonNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Biological AnthropologyDocument4 pagesIntroduction To Biological AnthropologyElizabeth MooreNo ratings yet

- Pocahontas Geological SurveyDocument356 pagesPocahontas Geological SurveyNorman Lee AldermanNo ratings yet

- Oslo Region LithostratigraphyDocument17 pagesOslo Region LithostratigraphyalexandropouloulinaNo ratings yet

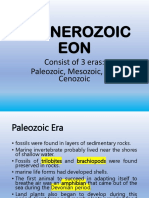

- Phanerozoic EON: Consist of 3 Eras: Paleozoic, Mesozoic, and CenozoicDocument17 pagesPhanerozoic EON: Consist of 3 Eras: Paleozoic, Mesozoic, and CenozoicSamantha BaldovinoNo ratings yet

- Evolution of WhalesDocument15 pagesEvolution of WhalesSanjanaSureshNo ratings yet

- Ikon Science SGreen Hydrodynamics AAPG2014Document10 pagesIkon Science SGreen Hydrodynamics AAPG2014Jhonatan_Valdi_8987No ratings yet

- Evidence Chart Key: Evidence What It Tells UsDocument2 pagesEvidence Chart Key: Evidence What It Tells UsJames 'jps' SimanjuntakNo ratings yet

- Everglades National Park and The Florida Keys - A Golden GuideDocument84 pagesEverglades National Park and The Florida Keys - A Golden GuideKenneth100% (8)

- TEST 4 Reading Actual TestsDocument42 pagesTEST 4 Reading Actual Testshoabeo1984No ratings yet

- Earth History and Geologic TimeDocument1 pageEarth History and Geologic TimeRemil CastañedaNo ratings yet

- Taphonomic Variability of Fossil Insects A Biostratinomic Study of Palaeontinidae and Tettigarctidae (Insecta Hemiptera) From The Jurassic Daohugou Lagersta TteDocument10 pagesTaphonomic Variability of Fossil Insects A Biostratinomic Study of Palaeontinidae and Tettigarctidae (Insecta Hemiptera) From The Jurassic Daohugou Lagersta TteDavid ArenasNo ratings yet

- (Advances in Parasitology Volume 86) Kramer, Randall - Yang, Wei-Zhong - Zhou, Xiao-nong-Malaria Control and Elimination Programme in The People's Republic of China-Academic Press, Elsevier (2014)Document448 pages(Advances in Parasitology Volume 86) Kramer, Randall - Yang, Wei-Zhong - Zhou, Xiao-nong-Malaria Control and Elimination Programme in The People's Republic of China-Academic Press, Elsevier (2014)Stoian Goranov100% (1)

- Balanced Cross Sections: A. DahlstromDocument15 pagesBalanced Cross Sections: A. DahlstromMuhammad Waqas100% (1)

- The Class MammaliaDocument5 pagesThe Class MammaliaMohammad Raza RizviNo ratings yet

- Impor Data Excel Ke ArgisDocument17 pagesImpor Data Excel Ke ArgisSumponoNo ratings yet

- Evidence Chart: Evidence What It Tells UsDocument2 pagesEvidence Chart: Evidence What It Tells UsnidhiNo ratings yet

- Variscan MetamorphismDocument65 pagesVariscan MetamorphismSARA MANUELA GUERRERO GIRALDONo ratings yet

- Reptiles Kerinci Seblat National Park SumatraDocument23 pagesReptiles Kerinci Seblat National Park SumatraAchmad Barru RosadiNo ratings yet

- Adaptive RadiationDocument7 pagesAdaptive RadiationSerenaUchihaNo ratings yet