Professional Documents

Culture Documents

ESP SIG Journal Issue 40 - v4 Final Version Mid Nov2012

Uploaded by

Ioannis PapadopoulosOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

ESP SIG Journal Issue 40 - v4 Final Version Mid Nov2012

Uploaded by

Ioannis PapadopoulosCopyright:

Available Formats

iatefl

Professional and Academic English

Journal of the English for Specific Purposes Special Interest Group

Courtesy of Joanna Dadelo-Madej, Krosno, Poland

Summer 2012 Autumn 2012 Issue 40

02 Editorial Prithvi Shrestha; From the ESP SIG Coordinator Mark Krzanowski 03 ESP SIG Committee 04 Transcending traditional academic boundaries: Designing and implementing a science communication course for science and engineering PhD students Mary Jane Curry 08 English first: ETTE leaves visible footprints in Nepal Laxman Gnawali 14 From VLE to PLE in English for Specific Purposes Elena Martn-Monje 19 New strategies in EAP and ESP teaching in Kazakhstan: Task-based approach application Saltanat Meiramova 25 Critical discourse analysis in ESP course design: The case of medical English Theron Muller 28 Monolingualism among multilingual scholars and its implications for EAP/ESP Ghanashyam Sharma 34 Assessment in making presentations: How it works best Elena Velikaya 39 Reports Turkey; Glasgow; Cuba; UK 44 Book Reviews Andy Gillett; Glenn Garrett; Meliha Mehmedova; Jessica Vicary and Katie Mansfield; Isora Enriquez O Farril; Joe Francis; Gillian Mckenna

Price 4.50 Free for ESP SIG members ISSN: 1754 - 6850

http://espsig.iatefl.org

www.iatefl.org

Sponsored by Garnet Education, publisher of ESP and EAP teaching materials.

www.garneteducation.com

Journal of the IATEFL ESP SIG

EDITORIAL

Index

02 Editorial Prithvi Shrestha; From the ESP SIG Coordinator Mark Krzanowski 03 ESP SIG Committee

Welcome

Welcome

Prithvi Shrestha, The Open University, UK

It is my pleasure to introduce you to the Summer Autumn issue. The journal has reached one of its milestones in its journey, as it is the 40 th Issue. As in the previous issues, it is packed with articles covering various topics in ESP, book reviews and conference reports. This issue, as usual, demonstrates the growing diversity of ESP geographically and in terms of topics. The contributors represent four continents: Africa (Sudan), Asia (Japan, Kazakhstan, Nepal), Europe (Spain, Russia, Turkey, UK), and North America (Cuba, US), and a wide range of disciplines in higher education including engineering and science. While some articles are research-based, others report on innovative practices in local ESP contexts. We would like to encourage all our readers to submit articles to the journal. Please visit http://espsig.iatefl.org for further information (also see this issue). Finally, we are grateful to our colleagues at Garnet Education for their continuous support in publishing this journal. Words of thanks also go to colleagues from CUP and OUP for supporting us through their advertisements in this journal.

04 Transcending traditional academic boundaries: Designing and implementing a science communication course for science and engineering PhD students Mary Jane Curry 08 English first: ETTE leaves visible footprints in Nepal Laxman Gnawali From VLE to PLE in English for Specific Purposes Elena MartnMonje New strategies in EAP and ESP teaching in Kazakhstan: Task-based approach application Saltanat Meiramova Critical discourse analysis in ESP course design: The case of medical English Theron Muller Monolingualism among multilingual scholars and its implications for EAP/ESP Ghanashyam Sharma Assessment in making presentations: How it works best Elena Velikaya

From the ESP SIG Coordinator

Dear Colleagues,

It gives us great pleasure to offer our readers and members Issue 40. I am very grateful to Prithvi for exceptional and consistent perseverance with the demands of the work on the journal, including academic rigour and attention to detail. Naturally in IATEFL this effort comes over and above our regular work, but we all know how rewarding the final product is. Prithvi and I are in turn very grateful to Garnet Education for the patience and final professional publishing touches that we truly appreciate. Special thanks go to the ESP SIG Committee members and long-standing members; particularly to Aysen Guven for her report from a recent EAP Conference in Turkey, and also to Andy Gillett who has been consistently reviewing ESP and EAP titles for the journal and this issue is no exception. Words of gratitude are also offered to the EAP team in CELT (the Centre for English Learning and Teaching) at the University of Westminster who, in their team effort, have kindly provided five book reviews for this issue. I hope our readers and members enjoy Issue 40 of the journal! Mark Krzanowski

IATEFL ESP SIG Coordinator Disclaimer The ESP SIG Journal is a peer-reviewed publication. Articles submitted by prospective authors are carefully considered by our editorial team, and where appropriate, feedback and advice is provided. The Journal is not blind refereed. Copyright Notice Copyright for whole issue IATEFL 2012. Copyright for individual contributions remains vested in the authors, to whom applications for rights to reproduce should be made. Copyright for individual reports and papers for use outside IATEFL remains vested in the contributors, to whom applications for rights to reproduce should be made. Professional and Academic English should always be acknowledged as the original source of publication. IATEFL retains the right to republish any of the contributions in this issue in future IATEFL publications or to make them available in electronic form for the benefit of its members.

14

19

25

28

34

39 Reports Turkey; Glasgow; Cuba; UK 44 Book Reviews Andy Gillett; Glenn Garrett; Meliha Mehmedova; Jessica Vicary and Katie Mansfield; Isora Enriquez O Farril; Joe Francis; Gillian Mckenna

Journal of the IATEFL ESP SIG

ESP SIG Committee

ESP SIG Coordinator:

Mark Krzanowski Acting Director of CELT (Centre for English Learning and Teaching) Principal Lecturer in ELT: Department of Modern and Applied Languages (MAL) Lecturer in English and Linguistics: Department of English, Linguistics and Cultural Studies (ELCS) University of Westminster 309 Regent Street, London W1B 2UW, United Kingdom E-mail: markkski2@gmail.com or ESPsig@iatefl.org

ESP SIG Journal Editors:

Ruth Breeze Instituto de Idiomas Universidad de Navarra C/Irunlarrea s/n 31080 Pamplona, Spain Tel: +34 948 425651 Fax: +34 948 425649 E-mail: rbreeze@unav.es

Assistant Editors:

Meenakshi Raman Birla Institute of Technology and Science Pilani, Rajasthan, India E-mail: raman.mee@gmail.com Modupe Alimi University of Botswana Gabarone, Botswana E-mail: alimimm@mopipi.ub.bw

Prithvi Shrestha Department of Languages Faculty of Education and Language Studies The Open University Walton Hall Milton Keynes MK7 6AA United Kingdom Tel: +44 1908 654265 Fax: +44 1908 652187 E-mail: p.n.shrestha@open.ac.uk

ESP SIG Discussion List Moderator:

William Nash Teacher trainer and EAP Tutor, University of Sheffield E-mail: w.nash@sheffield.ac.uk Aysen Guven EAP Coordinator, Bilkent University, Turkey E-mail: caysen@bilkent.edu.tr

Membership Secretary: ESP Reporter:

ESP SIG Webmaster:

Tek Raj Joshi E-mail: joshirajtek@gmail.com

Tawanda Nhire Nelson Antonio Pedagogic University, Maputo, Mozambique E-mail: tawandanel@yahoo.com.br

ESP Representative for Angola: Leonardo Makiesse Ntemo Mack ESP Representative for Brazil: Rosinda Guerra Ramos ESP Representative for Cameroon: Martina Mbayu Nana ESP Representative for China: Cindy Chang ESP Representative for DRC (Democratic Republic of Congo): Raymond Sangabau Madiambwele ESP Representative for India: Albert PRayan ESP Representative for Japan: John Adamson ESP Representative for Mozambique: Tawanda Nhire Nelson Antonio ESP Representative for Russia: Tatiana Szelinger ESP Representative for Saudi Arabia: Majed Alqahtani ESP Representative for Southern Russia: Olga Lomakina ESP Representative for Turkey: Aysen Guven ESP Representative for Zimbabwe: Runyararo Magadzire ESP Representatives for Ethiopia: Abayneh Haile & Mehari Berihe ESP Representatives for Oman: Saleh Al-Busaidi & Saeed Al-Saadi ESP Representatives for Pakistan: Mohammed Zafar & Saba Bahareen Mansur ESP Representatives for South Africa: Bernard Nchindila ESP Representatives for West Africa: Sunday Duruoha Sotarius & Adejoke Jibowo ESP Representatives for Yemen: Abdulhameed Ashujaa & Nagm Addin Abdu

October 2012, Issue 40 3

Journal of the IATEFL ESP SIG

Transcending traditional academic boundaries: Designing and implementing a science communication course for science and engineering PhD students

Mary Jane Curry, University of Rochester, New York. E-mail: mjcurry@warner.rochester.edu

Abstract

This article describes a genre-based communications course for science and engineering PhD students participating in a National Science Foundation cross-disciplinary training program. Designed to raise students awareness of how various professional written genres function for multiple purposes and address multiple audiences, the course is grounded in text sets compiled from the University of Rochester science and engineering professors that draw on the same research base to reach different audiences (e.g., grants, articles, press releases, public talks). Students in the course worked to analyse the linguistic and rhetorical features characterizing the various genres represented in the authentic texts. The professors contributing these texts and a university public relations specialist visited as guest speakers. Students also read a textbook on the role of science communication in society. Using the analytic tools introduced in the course, teams of students analysed a text set, then wrote individual abstracts for both disciplinary specialist and general nonspecialist audiences. This approach has the potential to be applied to text sets across disciplinary and geolinguistic contexts where instructors have access to authentic texts and, ideally, the authors of such texts. Keywords: science communication, graduate training, genre, academic writing.

funded at the University of Rochester; a private, small research university in Rochester, New York, United States. I begin by providing an overview of the program, then describe the design of the course, Communicating Science for Multiple Audiences and Purposes, and report on its implementation in the first two years of the five-year program. I conclude by discussing some of the issues that designing and teaching the course raise for teachers and researchers of advanced academic literacy.

2 The IGERT program: Distributed renewable energy: From science and technology to entrepreneurship and policy

1 Introduction

In recent decades, governments, universities and industry have increasingly recognized the need for scientists and engineers to acquire a broader perspective on how science and technology are integrated into society than they typically glean from disciplinary courses. To this end, in 1998 the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) established an Integrative Graduate Education and Research Traineeship Program(IGERT) that aims: to meet the challenges of educating U.S. Ph.D. scientists and engineers who will pursue careers in research and education, with the interdisciplinary backgrounds, deep knowledge in chosen disciplines, and technical, professional, and personal skills to become leaders and creative agents for change. The program is intended to catalyse a cultural change by establishing innovative new models for graduate education and training in a fertile environment for collaborative research that transcends traditional disciplinary boundaries. (NSF IGERT project summary, 2008) In this article I report on the design and implementation of a science communications course as part of an IGERT program

As the programs title signals, the content focus of the proposed IGERT program was renewable energy, a timely topic that crosses many disciplinary borders including science, engineering, economics, psychology and education. As the University of Rochesters proposal to the NSF articulated: With the rising economic, political, and ecological costs of fossil fuels, the development of clean and renewable energy sources has emerged as a global priority. Solar energy, the most abundant and widespread renewable energy source, is viewed as one of the best hopes for our future energy needs. However, solar energy is locally intermittent and its present cost is prohibitive. To solve these problems, we propose an integrated program of research, training, and education on Distributed Renewable Energy (NSF IGERT project summary, 2008, p. 1) After explaining the technological benefits of the program, the proposal asserts that Novel educational and training programs that transform the IGERT students into entrepreneurs and leaders will be implemented (ibid., p. 1). Further, the Vision, Goals and Thematic Basis section of the proposal expresses a goal to create a multidisciplinary community where scholarly research blends with entrepreneurship and policy, academia, government and industry work synergistically, and students develop first-hand understanding of all the key aspects of the global energy problem through a multidisciplinary graduate curriculum that transcends traditional academic boundaries; and pedagogical innovations relevant to teaching in other cultures and communication across disciplines (ibid., p. 3). To meet this goal, in addition to taking disciplinary courses, IGERT students enroll in four short, two-credit courses created for the program: Energy Economics, Policy and Systems; Academic, Industrial and Government Careers; Living, Teaching and Working in Africa and Communicating Science for Multiple

Journal of the IATEFL ESP SIG Purposes and Audiences, (the topic of this article). These required courses are credit bearing, taught by content-area specialists and scheduled in winter and spring intersessions to avoid conflicting with students disciplinary programs. the faculty members who provided text sets. The talk, which was delivered at the Rochester Museum and Science Center, provides an illustration of how a scholar successfully adapts scientific content for a non-technical (albeit well-educated) audience and, through the use of analogy, illustration and humour, makes a public presentation engaging and enjoyable. This same scientist has also appeared on public radio programs which I have not yet been able to record so I play a public radio program, Science Friday (www.npr.org), in class and ask students to analyse how the scientific content is presented for a public audience. (Interestingly, students do not appear to listen to radio regularly and many are unaware that science programs are broadcast on radio.)

3 Design of the Communicating Science course

In approaching the design of the science communication course, two broad goals guided my thinking: (1) to raise science and engineering PhD students awareness of how communication features change in response to the needs and interests of various audiences and purposes; and (2) to engage students in discussions of how scientists communicate to different public audiences plays an important role in societys understanding of and support for science, including public funding for research.

3.2 Course schedule and activities

3.1 Course components

To achieve these goals, the Communicating Science course involves students in analysing sets of authentic texts written by researchers and public relations staff at the university; interacting with researchers and staff who make guest visits to the class; listening to or watching science programs on radio and video and reading selected chapters from Practising science communication in the information age: Theorising professional practices (Holliman, Thomas, Smidt, Scanlon, & Whitelegg, 2009). This textbook covers topics ranging from trends within scientific communication (e.g., access to science, cross-disciplinary communication, peer review) as well as between scientists and larger society (access to new knowledge, ethics, patents, dissemination of knowledge, engaging with the public). My philosophy of teaching academic communication is grounded in social practice theories (Lea & Street, 1998; Lillis, 2001; Lillis & Scott, 2007) that view academic literacy as a set of social practices, enmeshed in social and political relations, rather than as only discrete individual skills. The academic literacy/literacies perspective is compatible with genre approaches (e.g., Artemeva, Logie, & St-Martin, 1999; Swales, 1990) to helping students understand how a range of authentic scientific texts functions in relation to multiple purposes and audiences. Variously, genre approaches view texts as representing a form of social action (Miller, 1984) in that they are meant to do something in a specific context, for specific reasons or purposes and with specific audiences in mind. Using an examination of the contextual reasons for the creation and dissemination of texts as a starting point allows for the application of more conventional approaches to understanding and teaching writing (such as focusing on grammar and mechanics), as these concerns are then situated in the larger social aspects of communication. The three faculty text sets included research grant proposals (and their component parts such as a non-technical summary, abstract, main sections); journal articles (including full-length research articles, letters, an overview article in a section of a journal called News and Views); conference papers and referees reviews; book chapters; scholars correspondence with journals and press releases written by university publicity staff about the research reported in faculty text sets. In addition to exploring these print genres, course texts include aural and visual texts. In class I show a videotape that I recorded of a public talk on nanotechnology given by one of

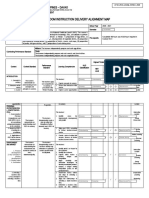

As noted, Communicating Science is a short, two-credit course. In the first year of the program the course met four hours per day for only one week (Monday to Friday), which turned out to be too intense a schedule that left students insufficient time to do the activities they needed to work on outside of class. In the second year, the course met for two hours per day over ten days, with students also attending the economics course for two hours daily. The course activities begin with students working in pairs to identify the genres represented by six extracts from texts ranging from real estate; personal advertisements; a popular science article; research grant and a journal article (adapted from Roe & den Ouden, 2003). For each extract, students hypothesize about its audience and purpose as well as the (con)textual evidence that enables them to determine the genre. A discussion of the notion of genre ensues with each team presenting evidence for how it identified an extract. Next I introduce the notion of move structures (Swales, 1990) as identified in grant proposals (Connor & Mauranen, 1999), followed the next day by analysis of the move structures of introductions to research articles. Students then watch the videotape of the professors lecture and explore press releases, referee reports for a submitted conference paper and online science as discussed in a textbook chapter (Montgomery, 2009). Interwoven into these discussions are activities on the use of register, terminology or jargon, nominalization, active and passive voice and first person pronouns across different texts. The readings on scientific controversies support class discussions of the impact of communicating about science on the publics understanding of and support for science. At the beginning of the second week students bring in their drafts of two types of abstracts for the final assignment: to write an abstract of their proposed or current research for a scientific audience and the same content reformulated for a general audience as a non-technical abstract. They engage in peer review, providing feedback on each others drafts. Then pairs of students present linguistic analyses of generic variation across text sets, again addressing questions of audience and purpose and providing (con)textual evidence for their claims. Visits from two professors who provided text sets, as well as a writer from the public relations department, offer the opportunity for students to ask questions about texts resulting from their analyses and to learn from these professional communicators. Figure 1 maps the objectives listed on the syllabus against the pedagogical approaches used in the course.

October 2012, Issue 40

Journal of the IATEFL ESP SIG Course objectives (Students will:) Learn to identify and understand a range of types of texts (genres) produced for scientific purposes and audiences, including fellow scientists, students and the general public Pedagogical approaches Genre awareness: identifying audience(s), social contexts, purposes (to get funding, to disseminate new knowledge, to build a CV, etc.) Textbook readings and discussion, interacting with guest speakers Analysis of move structure: identifying how sentences function and cohere in developing an argument; use of citations, evidence Linguistic analysis of register (formality, use of terminology, nominalizations, assumed knowledge on the part of the reader, etc.) Synthesis of experiences in identifying genre, moves, language use Additionally, the fast-growing cells can be harvested as a biomass source for gasification or other cellulosic processes. used in cosmetics, food products and biodiesel production. To decrease the production cost in an algae-based industry, we can genetically engineer the algae to grow faster, consume fewer resources, or increase production. Biologists are constantly searching for new genes (segments of DNA) that accomplish this, creating the need for efficient ways to inject those genes into the algae cells.

Analyze the structure of these texts and how it relates to textual purpose and specific audiences (e.g., persuasion, illustration, demonstration) Do micro-analyses to understand how language constitutes these texts to achieve the goals of the writer in relation to particular purposes and audiences Gain practice in creating textual genres from the same base of scientific/technical content for multiple audiences and purposes

Figure 2: Opening lines from a students abstracts for different audiences More specifically, these versions of research abstract illustrate the students awareness of the need to define scientific terms, contextualize science in a broader context and provide examples for a non-technical audience, whereas the student clearly assesses a more advanced level of understanding for an audience of scientific peers. Differences in the length of these extracts reflect the students genre awareness, with the non-technical abstract being almost twice as long (98 words compared with 59 words).

3.4 Students responses to the course

Figure 1: Relationship between course objectives and pedagogy

3.3 Student learning in the course

In both years of the course, students (12 in the first year and five in the second year) have clearly learned content. Presentations of student team or group linguistic analyses across the genres included in the text sets demonstrated a strong grasp of the linguistic concepts I hoped to teach, as well as students facility with identifying textual and other evidence to support their analyses. The assignment to write two versions of the final abstract for different audiences demonstrates that students can competently modify texts for audiences with different levels of technical knowledge. For example, Figure 2 provides extracts from two abstracts written by one student: For a scientific audience Microalgae have become an attractive platform for developing renewable biofuels because they harness solar energy to fixate carbon dioxide from the atmosphere via photosynthetic pathways. They are currently being investigated for their ability to produce hydrogen gas, lipids for biodiesel, and ethanol. For a non-technical audience Microalgae are single-celled organisms that undergo photosynthesis, meaning they convert sunlight and carbon dioxide into larger molecules such as carbohydrates, proteins and oils. From an engineering perspective, there are many potential applications of algae in industry. They are currently

As documented in both my informal course evaluations and formal institutional evaluations, students responded well to the Communicating Science course. Some students have been surprised not to encounter the traditional writing course they were expecting, but they quickly became engaged in the course activities. As students are required to take the course, I was concerned that they would not be intrinsically interested, but the vast majority participated enthusiastically in activities and assignments. In their formal course evaluations some students noted the benefit of being in an unusual environment (a communications course) and thinking about topics they dont usually discuss. Informal evaluations on the textbook chapters and other readings varied depending on the reading; students in the first year of the course also overwhelmingly felt that writing journal entries for each class was too much for a short course. In the first year some students were apprehensive about writing a research proposal because they felt their grasp on their research topic was too weak to articulate well; however, after doing the assignment they considered it valuable also for refining scientific ideas. One student noted that this assignment provided me with incentive to write now (emphasis original). Interestingly, in the second year students did not resist doing the final activity. Overall, students enjoyed the teams presentation of text set analyses, the guest speakers, and the videotape of the public science talk. They also found their peer review experience helpful in developing their ideas and how they had articulated these ideas for the specialist and non-specialist audiences. As one student noted on the informal evaluation, The peer review was very helpful in this course and helped to strengthen both my written and analytical skills. The final written project was also very helpful in learning and practicing how to write for a non-technical audience.

Journal of the IATEFL ESP SIG

4 Issues raised in designing and implementing the course

References

Both structural and internal issues arose in designing and implementing the course. In the first year, some students had a time conflict with the first-year examinations they were scheduled to take in the late spring or with regular research laboratory meetings. Even if these students could attend class, their priorities for focusing their intellectual efforts were elsewhere. By the second year, the IGERT program director had resolved this issue with other university faculty members and most students were more focused on the course. Internal to the course design, because I was not familiar with what IGERT students would know or be interested in in terms of scientific communication, I asked them to complete a preliminary questionnaire. It asked for students thoughts about the types of communication scientists typically engage in; the kinds of professional scientific writing students had already done and in what contexts; any significant previous writing experiences; their strengths and struggles with professional scientific writing; the kinds of communications they anticipated needing to do in the future; their writing process and experiences with peer review; and what they hoped to get from the course. Many students had previously engaged in some scientific writing and very few had strongly negative feelings about writing or being required to take the course. My focus on genre rather than on the mechanics of writing provided a frame for the course from the start that grabbed students attention and engaged them in the course. Given the range of the courses aims to raise student awareness of genres of communication in science and engineering, to engage them in larger conversations about science and society and to give them practice in writing and peer reviewing authentic texts, it is perhaps not surprising that 20 hours of contact time seemed insufficient, although spreading the course over two weeks in the second year was an improvement. As I reflect on the order of presentation of various topics and scheduling guest speakers visits, I will continue to experiment in the third iteration of the course. The overall success of this course, however, suggests that is has applicability for other contexts, grounded as it is in authentic texts created by practitioners working in the fields that students intend to enter (as well as publicity staff, with whom students will likely interact in the future). By collecting similar text sets from working scholars (or practitioners) in particular fields, ESP instructors should be able to implement a similar approach to introducing students to the genres of their fields.

Artemeva, N., Logie, S., & St-Martin, J. (1999). From page to stage: How theories of genre and situated learning help introduce engineering students to discipline-specific communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 8(3), 301316. Connor, U., & Mauranen, A. (1999). Linguistic analysis of grant proposals: European Union research grants. English for Specific Purposes, 18(1), 4762. Holliman, R., Thomas, J., Smidt, S., Scanlon, E., & Whitelegg, E. (2009). Practising science communication in the information age: Theorising professional practises. Oxford: Oxford University Press/The Open University. Lea, M., & Street, B.V. (1998). Student writing in higher education: An academic literacies approach. Studies in Higher Education, 23(2), 157172. Lillis, T. M. (2001). Student writing: Access, regulation and desire. London: Routledge. Lillis, T.M., & Scott, M. (2007). Defining academic literacies research: Issues of epistemology, ideology and strategy. Journal of Applied Linguistics, 4(1), 532. Miller, C. (1984). Genre as social action. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 70, 151167.

Montgomery, S. (2009). Science and the online world: Realities and issues for discussion. In R. Holliman, J. Thomas, S. Smidt, E. Scanlon, & E. Whitelegg (Eds.), Practising science communication in the information age: Theorising professional practises (pp. 8397). Oxford: Oxford University Press/The Open University. National Science Foundation. (2008). Program solicitation NSF 09-519 Integrative Graduate Education and Research Traineeship Program. Washington, DC: National Science Foundation. Roe, S., & den Ouden, P. H. (2003). Designs for disciplines: An introduction to academic writing. Toronto: Canada Scholars Press. Swales, J. (1990). Genre analysis: English in academic and research settings. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press.

Dr Mary Jane Curry is associate professor at the Warner Graduate School of Education and Human Development, University of Rochester. She is co-author of Getting published in a multilingual world: Critical choices, practical strategies (forthcoming) and Academic writing in a global context: The politics and practices of publishing in English (2010).

October 2012, Issue 40

Journal of the IATEFL ESP SIG

English first: ETTE leaves visible footprints in Nepal

Laxman Gnawali, Associate Professor in ELT, Kathmandu University, Nepal. E-mail: lgnawali@yahoo.co.uk

Abstract

English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teachers English language proficiency has a greater role in the effective classroom delivery than that of the teachers methodological know-how. In an attempt to establish this idea, I present a report on a teacher training project for the primary English teachers conducted in Nepal. The training modality, and the issues and problems it dealt, with are discussed before highlighting its results. I begin by setting the scene of the non-native EFL teacher education context in general, and in particular the place of English in the school curriculum in Nepal, and the teacher education for ELT in Nepal. Keywords: English language proficiency, teacher education, non-native EFL teacher, medium of instruction, teacher professional development, needs assessment.

1 The non-native EFL teacher

Non-native English teachers have greater challenges than their native counterparts (Maingay, 1986). While non-native English teachers need to develop the know-how of classroom practices, their own command of the English language must meet the requirements of the foreign language classroom. Only when these teachers are able to use English as a language during their lessons will their students get at least some exposure to the target language. This means that on beginning their professional career, these English teachers are expected to have developed three skills: communication skills in English, a set of professional skills to be mediated in a foreign language and ideas about the nature of the language and what it means to learn a language (Britten, 1988). Furthermore, they are also expected to have developed professional development skills to outgrow ideas about teaching and learning. Their proficiency in English gives them a basic skill to use in the classroom and boosts their confidence as a teacher, but most importantly, this brings the only opportunity available for learners to be exposed to English input required for learning this language. The proficiency also plays a vital role in the teachers psychology. The English language proficiency of the teacher determines how confident the teacher is in the classroom situation as Kamhi-Stein (2009, citing Murdoch, 1994 and Cullen, 1994) says, Language proficiency plays an important role in the teachers instructional practices since it may contribute to enhancing or undermining the teachers confidence, therefore, affecting the teachers instructional practices (ibid., p. 95).

2 The Nepalese context

English has a variegated status in Nepal. Though English has claimed its importance in every walk of Nepalese life, it is still a foreign language. It is required nowhere in the public official

processes and the Nepalese do not use it as a lingua franca. On the other hand, 13 per cent of the total schools in Nepal are private schools which use English as the medium of instruction (Department of Education, 2009). The public schools (known as government schools) use Nepali as the medium of instruction and have one English course in the school curriculum. The qualification of the primary school English teachers is only a tenth grade pass and this has created a problem in many ways. First, to allow only school graduates to work as teachers is not a rational decision as they are not emotionally mature enough to work with the children because they have just turned 15 themselves. Second, the English level they have is not advanced at all to work as teachers. What is more crucial is that they simply have not had enough exposure to English. Most of these English teachers come through this public system and they learn English at the age of nine or later. When they learn it, the only opportunity for them to experience English in use is in the classroom. Unfortunately, this does not happen as the medium of instruction is Nepali or any other local language the teacher speaks. Due to the lack of their exposure to English, they cannot use English for the communicative purpose even within the classroom setting. The Grade ten graduates who have very good proficiency are those who come from the private schools and unfortunately those who come this way hardly choose teaching as a profession in the public system. Though English is not used in the official system, the fact that English is given a high value by the state of Nepal is reflected in a recently implemented government policy: English from Grade I instead of Grade IV and complete revision of the school English curricula. The government made this decision in 2003 as a reaction to the private schools English medium policy. In fact, English as the medium of instruction was the sole reason the parents who could afford to send their children to private schools. Moreover, private schools topped all the national examinations. In some districts, some public schools have closed down in want of students as the local children have gone to the nearby private schools. With a view to enhancing teachers classroom performance for the changed situation, the Ministry of Education planned and implemented teacher training for all primary school English teachers and declared that 98 per cent of the 31,000 primary English teachers had been trained. (National Centre for Educational Development [NCED], 2010, p. 2). However, the performance of English teachers is far below a satisfactory standard for the same reason discussed above. Another reason why the teachers do not develop English proficiency is that teacher training programmes in Nepal have methodology as the only component and no consideration for the language proficiency. NCED runs a training programme divided into three packages (NCED, 2004):

Journal of the IATEFL ESP SIG Basic teacher training programme first phase (330 hours delivered face to face over three months) Primary teacher training second phase (660 hours delivered through distance mode) Primary teacher training third phase (330 hours delivered face to face over three months) Looking at the number of hours and the varying delivery modes, one can assume that the programme is promising. In the face to face mode, the teachers are brought to the training centres where they get ideas on dealing with the textbooks they have to teach. They also demonstrate their teaching skills through peer teaching. In the distance mode as well, the tasks focus on the how aspect of teaching English. The NCED has also introduced Teacher Professional Development (TPD) activities for these teachers, and again the support given is only orientating of the curriculum and textbooks, reading and reflecting on the appropriate ways of lesson delivery. Improving their own command of the English language itself is completely ignored. It was at this juncture in time that the English for Teaching: Teaching for English (ETTE) project was implemented jointly by the state and non-state sectors. the needs of the teachers working throughout the country. A cadre of young language teacher trainers would be trained first who would then go to the districts to train teachers in English language. The trainers would be called SuperETTEs, coined by joining super and ETTE. The teacher training would consist of 120 hours and would be followed by support mechanisms and self-access unit resource centres. The first year activities to run in three districts as a pilot, would be replicated with necessary modifications to make it more effective in six other districts over the period of the next two years (i.e., 2009 and 2010). The British Council in Nepal would collaborate with the partners at the planning, preparation and operational level. In preparation, the project team had several rounds of meetings and developed an outline of the activities which will be discussed below.

5 The training districts

3 The ETTE project launched

The ETTE teacher support project was launched in 2008. The three-year project initiated by the British Council ran in partnership with the Nepal English Language Teachers Association (NELTA), Global Action Nepal (GAN) and the Ministry of Education (MoE). The four project partners had their own significance. The British Council was the lead agency for funding and over-all collaboration. The partnership with NELTA and GAN was to bring together the key stakeholders (i.e., teachers and those who were working for them). The partnership with the state sector was significant for the implementation of the project and internalization of the project elements into its teacher education system once the project was over. ETTE as a language and methodology project was aimed at improving access to English for learners by upgrading the skills and increasing the confidence of teachers. The project also aimed to improve the classroom performance of teachers of English who have not had much previous access to support activities and operate in remote, marginalized and under-resourced areas and increase teachers access to a variety of developmental methods and ELT materials. The project expected that the MoE would buy this project and would institutionalize its elements in its system in the way it operated during the implementation period.

As a pilot activity for the first year, there were many things to be tested and learnt. To cover the geographical diversity of Nepal, Solukhumbu (mountain region), Baglung (hill region) and Kailali (the plains in the south) were chosen for the first year. Within the districts, teachers were selected from specific Resource Centres1: 24 teachers from one centre. There were three groups in Kailali and Baglung each and two in Solukhumbu.

6 Selection of the trainers

A group of SuperETTEs were now to be recruited and trained. For this, the partners considered recruiting fresh graduates with a MEd in ELT who were not yet employed. It was thought that graduates would not look for specific perks, they could be trained for this purpose as they were fresh and numberwise and, there would be a lot of choice. Each year during the project, a new group of trainers would be trained so that by the end of the three years, there would not only be primary school teachers with increased ability to teach effectively, but they would have a good number of teacher trainers in the country who may continue to develop other teachers ability in the language and methodology. So, it was decided that those who had just completed a Masters in ELT from Nepalese Universities, and were unemployed, would be invited to apply. A team of young MEd ELT graduates were recruited as SuperETTEs (language trainers) and trained to deliver the training to primary teachers. The trainers were selected for having both good English and good theoretical knowledge of ELT and for their clear commitment to a career in ELT.

4 Contextualizing the project intent

Once the project was approved, a project visioning workshop was organized in Almaty, Kazakhstan. It was attended by the British Council project managers/officers and key partners from all implementing countries. From Nepal the partner representatives from the MoE, NELTA, and GAN attended the workshop. Though the project aims had been spelt out, there were no concrete country-specific activities detailed. The aim of the workshop was to decide what exactly a country would do under this project. When the Nepal project brainstormed together, it was unanimously decided that the project would be to help primary teachers with their language. The workshop made some other important decisions. The project would operate in a cascade model in order to meet

7 Trainers training and training preparation

The SuperETTE training course was developed and delivered by a team of tutors bringing together a wide range of training experience from across the British Council and Nepal. This training was intended to equip the trainers with practical techniques. So, the course comprised of input sessions, followed by observed teaching practice (teaching the guinea pigs) with peer and tutor feedback. The feedback was followed by group lesson planning and observation of experienced

1 A Resource Centre headed by a Resource Person supports 15 to 25 primary schools. The support includes teachers training, materials supplies and physical facilities.

October 2012, Issue 40

Journal of the IATEFL ESP SIG British Council teachers in action. The methodology of this trainers training followed the experiential learning approach (Kolb, 1984, as cited in Dennison & Kirk, 1990). In this approach the participants reflect on past experience or sessions thereby making sense of what works. Based upon this learning, they plan further actions. The cycle of action and reflection is the centre of this methodology. To be involved in an action is to undergo an experience (Gnawali, 2001). The most important aspect of experiential learning is based on the relationship between this action, the individual experiences and the subsequent learning that takes place (McGill & Beaty, 1992, p. 26). The idea that learning takes place as a result of experience has been highly supported in the professional literature. In the words of Rogers (1961) experience is the primary source of learning, the highest authority, the touchstone of validity (p. 23). Kolb (1984, as cited in Dennison & Kirk, 1990) says immediate personal experience gives life, texture and subjective personal meaning to abstract concepts and at the same time (p. 21) provides a concrete, publicly shared reference point for testing the implications and validity of ideas created during the learning process. This implies that learning can take place in the light of past and present experiences. Following this idea of learning from experience, the experiential approach was followed throughout the course, creating a climate for the SuperETTEs to learn from their past and immediate experiences. Past teaching learning experiences Participating in sessions DO Concrete experience Action The SuperETTEs also learnt to reflect on the methodology of the input sessions and to consider how these techniques could be transferred to the local teaching context. A big difficulty was to find suitable language teaching materials. In the end, New Headway Elementary, published by Oxford University Press, was chosen as it was widely available, easy to teach and economical! One of the biggest challenges for the SuperETTEs was to make their teaching studentcentred. Coming from a traditional learning background, they themselves taught in a very teacher-centred way but as one SuperETTE said, This course has helped us to transfer our theoretical knowledge into practical one. The way we are asked to manage the classroom in teaching practice sessions is fantastic, learning quite new techniques. (Kathmandu, 12 June, 2008) Another agreed, The teaching practice sessions make us practically sound and helps us employ theory in practice. (Kathmandu, 12 June, 2008) Finally, the SuperETTEs compiled a bank of classroom English phrases from their observations for their own use.

8 Needs assessment

Teachers apply their learning in subsequent action: observations and action research

Reflection

Grids, dialogues with peers, reflecting in the sesions with the facilitators and other participants

REVIEW Reflective observation

A needs assessment was conducted to identify those teachers who actually needed support. For this, while the SuperETTEs training was going on, the project partners, in coordination with the District Education Offices (DEOs) and local implementing partners, identified the Resource Centres (RCs). Once the DEOs and the local partners mapped the districts and selected the RCs they then met with the Resource Persons who headed the RCs. It was decided that if possible one group of 24 teachers should be taken from one RC so that the teachers would keep working together even after the training. The Resource Persons heading the respective RCs then invited the English teachers to the needs assessment session. The teachers were given a standard British Council test, pitched at Level A1 of the Common European Framework of references. The test revealed a very interesting scenario; most teachers spoke virtually no English as exemplified by the following excerpt taken from an internal circulation of the British Council Teaching Centre. Whats your name? Richard Cox asked a primary school teacher in the remote Everest region, in a school an hours walk from the district headquarters. My name is Prabhu Shrestha Do you teach English? Yes, I English teacher. How long have you been teaching English? Huh? How many years have you been teaching English? Huh? It turned out that Prabhu had been teaching English for ten years, yet could not say much more than a few greetings. This is the reality in the remoter regions of Nepal. The same report further states Further needs assessment visits in the hills and the plains highlighted the same worrying fact many primary teachers cannot speak English. As a result, their students leave school unable to communicate in

They learn about the process of enquiry, the classroom practices and themselves Figure 1: Experiential learning cycle. Adapted from Kolb (1984, as cited in Dennison & Kirk, 1990, p.4) The idea of the above four-stage cycle concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation and active experimentation is based on the experiential learning model propounded by Kolb (1984) Figure 1.

APPLY Active experimentation

LEARN Abstract conceptualisation

10

Journal of the IATEFL ESP SIG English and ultimately unable to get good jobs. The needs assessment also included questionnaires and focus groups in order to determine their perceived needs and challenges. The findings from these tools revealed that the teachers wanted content rather than methodology. Although they wanted both they stressed that until they had at least a basic knowledge of English, methodology would be of no use. Teachers told us that if they had adequate knowledge of English, they could work out ways to teach it in their circumstances. Some of the quotes from the focus group included: We have not had training on language. We have had enough methodology. We need English so we can read and teach. If I know no language, what do I teach? We can teach if we can speak. The focus group with the other stakeholders, namely School Management Committee members and head teachers, echoed the same. The following are some of the responses from those stakeholders: We need to give teachers a lot of practice in English. Language training is required. Everyone has had training but they do not use it. The transfer of training from training hall to classroom has failed. Teach English please. In a socialization meeting, School Supervisors from the DEO said they are ready to help to improve primary teachers English the best way they can. It also became apparent in discussions with DEOs and RC officers in the districts that this is because all primary schools have to have teachers of English, but there are not sufficient teachers who have the language to go around. So people who have almost no competence in the language, and who teach several other subjects, are allocated. With this situation and the commitment from the stakeholders, the project team went ahead with the implementation plan. The plan further included the teacher training, follow-up and support. activities were used to teach English to the teachers and the methodology was taught implicitly. The participants reflected on their experience of learning English and realized how it should be taught. Teachers also planned lessons and practised teaching using the My English Book that they teach at school. Teacher learning During the Training After the Training Follow-up Input Reflection Micro-teaching

Content Mentoring Figure 2: Teacher training modality Drop-outs and late arrivals are a common phenomenon but this teacher training saw a completely different attitude. Nobody was late as they were staying at the same hotel where the training was held and there were no drop-outs. The participants decided that they would not miss any classes at any cost. This following excerpt from an informal report handed in by one of the SuperETTEs who was in Baglung reveals how the teachers took the training: All the PETs, NGOs and even officers from the DEO appreciated our hard work, training styles and punctuality in training. It was effective because we delivered training based on teachers need. In the beginning I was worried about the dropouts because it was lengthy training, but I was wrong. Few PETs (primary English teachers) were old with weak eye sight and used to sit near the window to read books. They brought powerful eyeglasses to overcome this problem but continued the training. The female teachers gave up their household work to attend the training. One of the PETs didnt take part in his daughters wedding preparation. It was only a day before the wedding, he said: tomorrow is my daughters wedding, can I go home after lunch break? We couldnt let him miss such an important event of his life. The training was ended with a grand closing ceremony. The effect of the training on the teachers and the government officials is reflected well in the following excerpts from the e-bulletin of the British Council: Our classroom will be different now. We used to teach English through translation method, now we will teach English through English, and we felt that we are achieving our goals. This was what, Mrs. Huma Thapa, an ETTE project participant from Baglung district had to say after completing the course and finding the difference in her own performance. Two teachers from Kailali district said that they learnt the way English can be learnt and taught. They said that the major achievement had been the confidence in speaking without the fear of making mistakes. When they spoke to Observation and feedback (at school)

9 Teacher training

Once the trainers were ready, the British Council and the partners the MoE, GAN and NELTA communicated to the local implementation partners who would coordinate with the Resource Centres in conjunction with the DEO to work with the local partners to select participants. The teachers, selected based on their needs assessment test session, were invited to the district headquarters for the residential training. They were put in a hotel where they would get lodging and full board. This provision was different from the usual training because in such training programmes, teachers are often given a daily allowance and they stay on their own. Because the teachers want to spend less and save money, they tend to find their own accommodation with relatives or friends, or they find cheaper places to stay, this results in them not paying enough attention to their learning. Now, the teachers had no worry as they were not handling money and were given good meals. Moreover, they were put in the same hotel and were not travelling, so they had ample time for socialising and practising English after the formal sessions. The lessons and materials prepared during the trainers training were used in the teacher training sessions. The major

October 2012, Issue 40

11

Journal of the IATEFL ESP SIG Mr. Gnawali, Vice President of, Nepal English Language Teachers Association (NELTA), they spoke in English and visibly they were not at all worried about the mistakes. Their English was not without flaws but they were expressive and fluent. Mahashram Sharma, Director General, Department of Education during the opening ceremony of training in Baglung said ETTE Training has given an opportunity for the government school teachers improving their English language. In todays global competition, English language is a must skill and ETTE training has helped the teachers to teach language in classroom and create English environment. Training like this will help our students to compete in the global context. (www. britishcouncil.org.np, 2009) 2) Teacher association membership: Thinking that the teachers would keep coming in contact with one another, they were encouraged to take membership of NELTA. In Kailai, they were given one-year membership with the project money. In Baglung, the ETTE trained teachers were invited to the NELTA office to use the resources and specific time was allocated for this. Many teachers paid for their own membership. In Solukhumbu, the teachers have decided to set up a NELTA branch. 3) Resource materials for self-learning: Though the teachers were enthused, they lacked resource materials for selflearning. So, each resource centre was given a set of readers, grammar books and ELT resource materials. The teachers from the respective RCs have developed plans on how to use them.

10 The Follow-Up

Without the proper follow-up, the effect of the training fizzles out. With this concept in mind, the follow-up was carried out through three different activities: observation and feedback, teacher association membership and the setting up of unit resource centres which I discuss below. 1) Observation and feedback: After the training the SuperETTEs were given orientation on observation and feedback and were sent to the districts. They travelled to the village school from where the teachers had come for the training. They held meetings with the head teachers, other staff members and in some cases with the school management committee members to inquire about the impact of the training. They sat with the teachers, observed their classes and gave feedback. The observation showed that the teachers were using English in the classroom and were trying their best to use a student centred approach. More than that the visit had an attitudinal change: they had never had a chance to show what they were doing; trainers had never visited their schools. One of the SuperETTEs reported as follows: In August, we went to visit the schools of our PETs. The purpose was to sell the ETTE concept to the school headmasters, parents, School Management Committee and other stakeholders. The visit was full of adventure. I was accompanied with one more SuperETTE and one resource person (RP) of that area. We walked for 18 hours with heavy luggage to reach the schools from headquarter. Every day we had to walk around 25 hours to reach the schools. It is really unforgettable experience for us. Despite of the natural obstacles (landslide, heavy rainfall, leeches on the way) that came our way, we proceeded with our selling visit. We enjoyed interacting with local people (teachers, School Management Committee, Parents, Teacher Association and students). They were interested and happy to talk about ETTE project. We received positive feedback from teachers, SMC, PTS. It was good to hear one of the head teachers who said I have attended more than 100 trainings during my 25 years teaching experience but this is the first time someone visited the schools for monitoring and supervision after training. Teachers found this training important to motivate students. There is a high demand of ETTE training in other regions and many PETs waiting for ETTE to come to their regions.

11 The lessons learnt

Once the teacher training was over the project partners met to reflect, in order to make sense of what has been achieved, again following the action reflection cycle (Figure 1). The project partners reflected along with the SuperETTEs after the first year activities were over. Upon reflection they decided that the project had been instrumental to drive home some important things. In the review meeting, the partners and the SuperETTES expressed their views which can be summed up as follows: a) The choice of language over methodology had been the right decision. Teachers really benefitted from the training. Without the language proficiency, the methodological skills are of no use. b) Partnership was the most important factor in the success of the project. The British Council was in no position to reach out to these teachers without the organisations they partnered with. Fragmented and isolated practice does not make good impact. c) Teachers learnt during off hours as well because they were with the group and were using English even for personal communication. Opportunities for using English for real purpose is a pre-condition for learning a language. English teacher trainings are best if they are residential. d) Full facilities freed the teachers from the worry. If they had been given cash, they would spend time calculating how to save. e) The choice of young MEd graduates had some benefits as well as some drawbacks. They met the expectations we had, as discussed elsewhere in the paper, but once the training was over they started asking the British Council if they would get the extension next year; if not they would look for jobs. The groups had lost some members before the end of the year. f) The government system is very useful if the officials are helpful and understand the project spirit. This was fine except that some officials expected monetary benefit for their cooperation and there was no provision in the budget as such.

12 After effects and implications

There have been several changes in the teachers lives after the training though very few have been reported. Those who got the NELTA membership have made visits to the NELTA resource centres and attended the conferences. The

12

Journal of the IATEFL ESP SIG Kathmandu Post National English Daily reported that one of the ETTE teachers bagged a national award. Mrs Janaki Pathak was awarded with the National Education Service Award by the Government of Nepal. Janaki says ETTE has made a big difference in my life; it is very difficult to express in words. The complete report is in the Appendix. The ETTE project results have shown significant implications for English language teacher training in contexts such as those of Nepal. The synergy between significant partners can create conditions for result-oriented training. The partnership among the British Council, NELTA, GAN and the MoE brought together the resources and the network of the government system along with the experiences of the professional organizations. Likewise, an intensive training course with a focus on language development and implicit touch on the pedagogy develops teachers confidence in both the language and the teaching methodology. Courses geared to the pedagogy alone cannot bring about the intended change in the EFL contexts.

Appendix

English Builds Self-Confidence

References

The British Council (2009). E-Bulletin. Retrieved March 12, 2009, from www.britishcouncil.org.np Britten, D. (1988). Three stages in teacher training. ELT Journal, 42, 38. Dennison, B., & Kirk, R. (1990). Do Review, Learn, Apply. Oxford: Blackwell. Department of Education (2009). Flash I Report, 2066 (200910). Bhaktapur: Department of Education. Gnawali, L. (2001). Investigating classroom practices: A Proposal for In-service Teacher development for the secondary school teachers in Nepal. An unpublished Masters Dissertation, the College of St Mark and St John/ University of Exeter, UK. Kamhi-Stein, L. D. (2009). Teacher Preparation and Non-native English Speaking Educators. In, A. Burns and J. C. Richards (Eds.), The Cambridge Guide to Second Language Teacher Education (pp. 91101). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Maingay, P. (1986). Observation for Training, supervision or assessment? In A. Duff (Ed.), Explorations in Teacher Training (pp. 118131). Harlow: Longman. McGill, I., & L. Beaty (1992). Action Learning: A Practitioners Guide. London: Kogan Page.

JUL 08 Janaki Pathak has no hesitance in saying that learning English helps develop self-confidence, Until a few years back, I couldnt even answer simple questions in English. But things have changed now. I can phrase sentences and can speak English comfortably. English is no more a difficult language for me. I am confident about speaking in public now. An English teacher at a remote village in the Far West, Janaki attended the English for Teaching, Teaching for English (ETTE) training series in 2008 and considers this experience as a turning point in her life. ETTE has made a big difference in my life; it is very difficult to express in words. My life has changed after attending the training. I have seen personal and professional growth in myself. I feel I have become a better teacher, says Janaki. The ETTE was a three-year project initiated by the British Council with the mission of improving access to the English language for learners by upgrading skills and increasing the confidence of teachers. The project focused on marginalised teachers in both remote rural areas and disadvantaged urban areas. The objectives were to improve the teachers classroom performance in both methodology and language, by enhancing their access to materials, methods and development opportunities. A teacher of grade one, Janaki has seen great improvements in her students level of speaking English. She mentions a 3550 percent increase in students pass rate in the English subject over the years. She expresses proudly, When I am satisfied with my teaching, I will be able to transfer that to my students. My students enjoy English classes now. They are more forward and are not afraid to ask questions. They are open to learning. Before the class ends, my students request me to sing English rhymes. That is the change I have seen in my students. Janaki was also a recipient of the National Education Service Award in 2008 a prestigious recognition given by the government of Nepal for a teachers outstanding performance. From http://www.ekantipur.com/the-kathmandupost/2012/07/08/creativity/english-builds-selfconfidence/236966.html

National Centre for Educational Development (2004). Secondary teacher training curriculum (10 months). Bhaktapur: National Centre for Educational Development. National Centre for Educational Development (2010) Teacher Professional Development: Trainers Training Manual. Bhaktapur: National Centre for Educational Development. Rogers, C. (1961). On Becoming a Person. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Laxman Gnawali is Associate Professor of ELT at Kathmandu University. He leads and facilitates degree and short-term teacher-training and trainer training programs for ELT. An author of EFL school textbooks for younger learners and special education learners in Nepal, he has also co-authored language improvement courses for English teachers. His national and international contributions include a book and articles on teacher development. His research interests include EFL teacher professional development through teacher networking.

October 2012, Issue 40

13

Journal of the IATEFL ESP SIG

From VLE to PLE in English for Specific Purposes

Elena Martn-Monje, Universidad Nacional de Educacin a Distancia (UNED), Spain. E-mail: emartin@flog.uned.es

Abstract

This paper discusses the potential of Personal Learning Environments (PLEs) in English for Specific Purposes (ESP), seen as a natural evolution from the widely used Virtual Learning Environments (VLEs). It shows the design of a course on Scientific and Technical English that makes use of various Web 2.0 tools (social bookmarking, blogs, wikis), with the premise that this software will encourage both collaborative work and autonomous language learning, while helping students create their own preferred learning path. The language teacher is seen here as a watermark: he or she has a presence in the background but lets students take responsibility for their own language learning. Keywords: autonomous learning, collaborative work, ESP, PLE, VLE.

1 Introduction

The purpose of this article is to investigate the suitability of PLEs for language learning and more specifically for ESP. It shows the design and implementation of a course on Scientific and Technical English and details the steps taken in order to help students create their own PLE, with the aim of making them successful autonomous language learners. This course combines autonomous and collaborative work and one of the main objectives of the research has been to look at the ways in which PLEs encourage collaborative work, participation and interaction. Furthermore, the author sought to explore the potential problems or benefits of a low teacher presence, conceived as a watermark, a low-key, restrained approach that stresses the pre-eminence of the language user in developing their learning. The use of VLEs is well established in foreign language teaching, with the majority of higher education institutions offering language courses through Moodle or Blackboard Learn - the most popular VLEs (Godwin-Jones, 2012). These are software tools that bring together in an integrated environment a range of resources that enable not only learners and staff to interact online but also the institution to provide learning materials and track students progress (BECTA, 2004). They follow a constructivist approach, founded on the premise that students acquire new concepts through their personal interpretation of the learning process and their own previous knowledge and beliefs (Dougiamas, 1998; Piaget, 1980; Papert, 1991, Vygotsky, 1978).

VLEs are ideal tools for e-learning (distance learning via webbased applications), since they permit students to work at their own pace, providing flexibility in the time and place allocated for study. They also allow for both individual and collaborative learning and foster interaction in the teaching group. However, with the turn of the century and the emergence of Web 2.0 applications, teaching practices are evolving rapidly and VLEs may not cater for the so-called digital natives (Prensky, 2001) that are accessing higher education these days. Godwin-Jones has rightly noted that the current generation of students is coming to campus with quite sophisticated technology skills and habits (2009, p. 3). They are completely at ease with the use of Internet in their professional and personal life and commonly find that universities employ these services in a much more old-fashioned way, with communication predominantly through email and interactions with instructors and peers through a top-down, fairly inflexible learning management system (ibid.). Here is where PLEs come into the picture. They are a natural evolution from the widely used VLEs (Attwell, 2007; Guth, 2009) and provide a more creative, adaptive learning environment, since they allow students to customise their set of resources and learning materials, blurring thus the distinction between formal and informal instruction: The idea of a Personal Learning Environment recognises that learning is ongoing and seeks to provide tools to support that learning. It also recognises the role of the individual in organising his or her own learning. [] Linked to this is an increasing recognition of the importance of informal learning. (Attwell, 2007, p. 2). PLE is in fact an umbrella term that can be applied to a wide range of tools, from e-porftolios (Buchem, Attwell & Torres, 2011; JISC, 2007; Salinas, Marn & Escandell, 2011) to web widgets (Godwin-Jones, 2009) or mobile phone apps (Underwood, Luckin & Winters, 2012). It is a relatively new concept, with varied conceptualisations, as reflected in the myriad of acronyms and terms to describe PLE, among others aPLE (adaptable PLE), mPLEs (mobile PLEs), iPLEs (institutional PLEs), PWLE (Personal Work and Learning Environment) and PRP (Personal Research Portal) (Buchem, Attwell & Torres, 2011). For the purposes of this paper, we will refer to PLEs in general and follow the definition provided by EDUCAUSE (2009, p. 1): The term personal learning environment (PLE) describes the tools, communities, and services that constitute the individual educational platforms learners use to direct their own learning and pursue educational goals.

14

Journal of the IATEFL ESP SIG and learning has led to a sixth role: facilitator, or person who helps learners to get their own understanding of the context, monitoring that the collaborative work is in place (MartnMonje, 2011). We can venture that with PLEs in ESP, the new studentcentred curriculum will eventually turn that facilitator role more into a watermark, whose presence will be subtly evident in the background. That does not mean that the students will be left to their own devices, but it implies that they will take responsibility of their own learning, resorting to their teacher/ instructor for support or guidance when needed. The following sections report on an initiative carried out at the Spanish National University for Distance Learning (UNED), to investigate how PLEs can be used in ESP.

Figure 1: Comparison between VLEs and PLEs (Guth, 2008) PLEs offer several benefits when compared to VLEs (see Figure 1): (1) they are more student-centred, since students can customise their learning resources; (2) they do not need to coincide completely with the VLE provided by the educational institution; (3) they blend formal, non-formal, and informal education and more importantly (4) they enhance additional skills, such as metacognition. A typical PLE, for example incorporates blogs where students comment on what they are learning (EDUCAUSE, 2009, p.1). This metacognitive competence is essential for language learning (Cohen, 1998; Graham, 1997; Macaro, 2006) and more so in ESP, where there is not a unique method that is valid for every student in every possible situation. On the contrary, language instruction must be tailor-made in order to meet the needs of learners in these specific contexts (Hutchinson & Waters, 1987) and in this context it is essential that language users can reflect on their own learning process effectively.

3 The study

3.1 Background context

2 Personal learning environments and language teaching

One of the authors that has intensively investigated the use of PLE in language teaching and learning is Guth, who believes that they are closely linked to collaborative work and Web 2.0 tools (2008, 2009). This author also applies a socioconstructivist approach to language instruction and aims to integrate both formal and informal learning. In her view, one of the strengths of the use of PLEs in languages is that, just like VLEs, they facilitate computer-mediated communication (CMC) in different formats (synchronous or asynchronous). The main difference, though, is that this CMC is usually done in an open format with PLEs contributions can be made without having to register online. PLEs also contribute to the development of the linguistic competence, as well as other skills relevant for autonomous lifelong learning. The language teacher that makes use of PLEs must take into account all these pedagogical considerations, and those practitioners who focus on ESP should put emphasis on enhancing the specificity of these linguistic sub-domains. Teachers and practitioners of ESP are said to have five key roles (Dudley-Evans & St. John, 1998): teacher; course designer and materials developer; collaborator; researcher and evaluator. The author of this paper has already argued that the inclusion of constructivist theories in language teaching

This exploratory study is based on the design of the course Scientific and Technical English in the postgraduate Masters programme English for Specific Purposes at the UNED. There has been previous work in this institution to overcome the limitations of second language e-learning, making use of the latest developments in computer technology and attempting to establish a theoretical framework for second language learning that combined individual and collaborative work (Read, Brcena & Rodrigo, 2010). The initiative followed by the author of this paper tries to overcome the limitations imposed by the VLE used in all the courses offered by UNED and explore the affordances of PLEs for language teaching and learning. The course was offered in the second semester of the academic year 20112012 and covered the following areas: professional activities related to Scientific and Technical English, Engineering, Medicine and Nursing and Computer Science. The course methodology was based on a combination of individual work, included in the VLE, and collaborative work that would make use of Web 2.0 tools and try to encourage students to create their own PLE. Figure 2 shows the framework for this course: E-mails Social bookmarking (Delicious)

VLE (Individual work)

PLE (Collaborative work)

Blog

Forums

Wiki

Figure 2: Framework for the use of PLE in the course Scientific and Technical English

3.2 Methodology

The course had a total of 20 participants, but only 17 students that completed all tasks were considered for research purposes. There was a predominance of women (76%) and most of them were not digital natives, 77% of them being over 30 years old. However, their digital literacy was evident, as stated in the profiling questionnaire that they completed, since they were all fully familiarised with Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) and used computers both for work and leisure (Figure 3). They also acknowledged

October 2012, Issue 40

15

Journal of the IATEFL ESP SIG to have accessed the online course from different devices, ranging from the traditional desktops to smartphones and tablet PCs (see Figure 4 below). Social bookmarking (Delicious, www.delicious.com): This social software was used in the initial module. Students were asked to share with their course mates some of the web links they found on the Internet related to Scientific and Technical English and ESP in general. Blogs (www.anurseabroad.blogspot.com): This task was designed with the purpose of enhancing collaborative writing. It was featured in the module for Medicine and Nursing and the students had to imagine that they were nurses working together in a specific English hospital, sharing their experiences in the blog. Wikis (http://elenamartinmonje.wikispaces.com): This Web 2.0 tool was used in two different ways. One task consisted in creating a collective summary of a book on ICT that all course participants had read, and the second one was the creation of a collective glossary of terminology related to Computer Science. Second phase: The actual completion of the tasks, with social bookmarking practised in module 1, the blog was included in module 3 and the wikis were left for the final modules, 4 and 5 (The collaborative task for module 2 was a WebQuest, not susceptible of being included as part of their PLE). Third phase: Students evaluation of the course.

Figure 3: Use of ICT for work and leisure

4 Research results