Professional Documents

Culture Documents

FlamencoMind ClassicalMind

Uploaded by

Ariel_BarbanenteOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

FlamencoMind ClassicalMind

Uploaded by

Ariel_BarbanenteCopyright:

Available Formats

This article was published in SoundBoard,the journal of the Guitar Foundation of America. Vol XXXI, No.

4, 2006 Flamenco Mind/ClassicalMind Valdemar Phoenix 2006

After a concert appearance or casual gig, guitar aficionados will frequently appear and ask me a question. The aficionados explain that they are currently studying classical guitar with someone and would like to know if there is a good book on flamenco that they can get because they would like to learn some flamenco. These aficionados almost always give me an estimate of their music reading ability, some saying that they can sight-read well, and some saying that reading music is a struggle. The implication to be drawn from this is that many classical guitarists conceive of the flamenco guitar in much the same way that they conceive of the classical guitar, and assume that the way to learn it is to get a book of musically-notated flamenco (with or without a teacher) and read through it. The aficionados are usually perplexed when I tell them that, although there are many books on the market, flamenco cannot be learned from a book.

The fact is that the classical guitarist and the flamenco guitarist have very different approaches to the guitar, and to the music of the guitar. In short, the classical guitarist has a 'classical mind,' and the flamenco has a 'flamenco mind,' and the two are, for the most part, like the two hemispheres of the brain itself. Each is dedicated to entirely distinct functions. This article will explore some of the major differences between the classical and flamenco minds, in an attempt to show the classically-oriented aficionado a path by which to approach, understand, and appreciate flamenco. We shall see how flamenco originated far from the influences of the classical guitar world and gain some insight into why the flamenco guitar has changed from a simple Andalucian acompaniment form to one of the most exciting world class music genres in recent guitar history.

Flamenco's Roots Let's examine the roots of the flamenco mind, and see how the origins of flamenco and classical guitar occured in very different places. To begin with, flamenco is not Western music. It is Indo-European and Mediterranean, and this reflects its relationship to the music of North Africa, the Middle East and the Indian Sub-Continent. These influences converged in southern Spain at around AD 700, when the Moors (today the Morrocans) conquered and occupied what has come to be Andalucia. The Moors were not evicted until AD 1492, but after almost 800 years, their influence on Spain was there to stay. At about the same time as the Moorish eviction, the Gypsies were moving in, and their origins and culture can be traced directly back to India. The music that was to become flamenco was cooking in a pot that included

strange instruments like the oud (which would later evolve into the lute), the n flute and strange singing styles that were related to the religious chants of the Moslems and Jews.

With this cultural background, it is clear that flamenco does not bear much relationship to so-called western classical music. Flamenco music is based on the modal scales common in the North African and Middle Eastern music. One of the modal scales that gives a characteristic flamenco sound is the phyrigian scale, still used today. In the classical world, modal scales are used mostly in ethnic music, liturgical compositions, or pieces evoking an ancient feeling. Most classical guitar literature, of the 19th Century at least, is in Major and Minor scales, unless it happens to be a Spanish (or ethnic) piece. Then it might touch upon the phrygian mode. But flamenco music lives in the phrygian and other modal scales.

Lifestyles of Early Classical and Flamenco Guitarists The early history of classical guitar music is based around composers and performers who were court composers in the employ of European nobility. Gaspar Sanz, Robert de Vise, Luis Miln, and many others of this era were all employed as court musicians and composers. Their music may often seem 'folk' based, but it is a courtly folk. Even when we enter the golden age of early 19th century classical guitar, with Sor and Giuliani, the aristocratic mold had already been set. This was thoroughly western music, treated in a thoroughly western fashion. The patrons of the classical guitarists were still the nobility and the rich. As for the music, the rules had been set by Haydn and Mozart, and the court composers who went before them. Although Sor was a Spaniard by birth, his career took place in Paris, for the most part, and there is nothing very Spanish about the bulk of his music, which included waltzes, minuets, sonatas, and other typical forms of the era. Also, many classical guitar methods arose at this time, designed to teach the educated man or woman how to play the guitar. The Italian schools were probably the most prominent, represented by Carcassi, Regondi, and others, while Sor and Aguado had their methodologies for the so-called Spanish school as well.

The flamenco during the early 19th Century is almost completely unknown, though there are vague historical references to it. We can infer that it existed, but certainly not in the courts. It arose from music of the non-aristocrats. It was in the streets, taverns, and private parties. Gypsies (and often prostitutes) were often hired by rich people to entertain at their parties. This is very reminiscent of Jazz's origins in the Storyville section of New Orleans, where drugs and prostitutes went hand in hand with Jazz. The history of flamenco definitely has its sordid side.

By the late 19th Century flamenco had caught the eye and ear of the public of Andalucia, and flamenco clubs began to open featuring local flamenco singers, guitarists, and eventually dancers. There is evidence that this was partly facilitated by the arrival of the Antonio Torres guitar, which was, according

to some, including noted guitar luthier Richard Brun 3, originally introduced as a cheap instrument for the flamencos, not as an aristocratic instrument for the noble classical composers.4 The Caf Cantante, as it was called, was essentially a small theater, often run by the local flamenco singer. It became the flamenco night club, and is the mother of today's tablao flamenco.

The early flamenco artists were certainly not 'schooled' musicians. They played with rasgueados (strumming techniques) and mostly a thumb ligado technique, which were to become the hallmarks of flamenco. A very few flamenco guitarists, in particular, Rafael Marn and Ramn Montoya, toyed with the classical guitar of the era, incorporating certain arpegios and classical techniques into flamenco. The move towards the classical had disastrous effects for Rafael Marn. Marn wrote a flamenco methodology book called Mtodo de Guitarra Flamenco por Musica y Cifra. It utilized both tablature (cifra) and standard written musical notation (musica). The response to it virtually ended his career and thrust him into obscurity. The classical guitarists considered him a flamenco guitarist because of the music he played. However, the flamenco guitarists considered him a classical guitarist because he could read music and had had been associated with Trrega! As a result, both groups rejected him, showing clearly the clash of minds. 5

The Cante and Baile The cante is the backbone of all flamenco. It is often called the mother of flamenco. Derived from Hindu and Semitic chants, the cante became the vocal style of the flamencos. In order to be a flamenco guitarist, one must understand how to accompany some 20 or so distinct styles of flamenco cante. These styles or forms have names like buleria, soleares, or alegrias. Each style can have many variations, but they are all structured according to a rhythmic and harmonic scheme. It is thoroughly useless to run out to the local music store and buy a piece of flamenco sheet music called Soleares or Buleria, and then try to accompany a flamenco singer with it. The cante has its own rules, structure and rhythm (and some have no rhythm!). The guitarist must literally accompany what the singer does, and go where the singer goes harmonically and rhythmically. In the old days, it was enough for a guitarist to know a few chords and the rhythmic structure, and just play along with the singer, more or less by rote. If you could accompany one singer, you could accompany them all. But soon it got more complicated. Singers got better and so did the guitarists. Today's flamenco guitarist must accompany a wide range of cantes, and be able to accompany anyone who sits down with him, on the spot. The professional flamencos must also invent their own melodies, called falsetas, with which to accompany the singer.

The Baile is the dance. The word is related to the 'Ballet, but there is nothing classical about flamenco dance. In the late 19th Century, flamenco dance began to evolve into the form we see today, and was added to the flamenco performance on a regular basis. A flamenco dancer is a percussionist as well a dancer, and the rhythms of flamenco are difficult and highly syncopated. The flamenco guitarist's job is

to accompany the flamenco dancer's constantly shifting rhythmical variations, following her or him with precise, percussive accompaniment. In addition, the guitarist must also play melodic falsetas to enhance the action, just as he does for the singer. These falsetas are often original, and sometimes copied from some other guitarist. But even when copied, they are often changed, altered, inverted, and disguised.

Now the classical guitar literature is filled with pieces called gigue, minuet, zarabande, tanz, Spanish dance, and even fandango (the fandango is one of flamenco's main forms). But you would be hardpressed today to find a classical guitarist who knows what these dances are, let alone how they were originally accompanied. The classical guitarist approaches these things as abstractions, not as actual dance forms. It is no surprise, then, that the classical player tends to view learning flamenco in the same abstract way.

Flamenco's Classical Recital Era Ramn Montoya was one of the first flamenco guitarists to start playing the flamenco guitar as a solo instrument. Others followed immediately, including the maestro and virtuoso Sabicas. Sabicas was to define what being a concert flamenco guitarist meant for much of the 20th Century.

Montoya and Sabicas essentially adopted the classical Segovia model of the guitar recital. (Of course, Segovia did not innovate the classical guitar recital format Trrega most likely did. 4) One guitarist, alone, sitting on the stage, playing a solo recital. It was a natural enough thing to do, since classical guitar recitals were certainly nothing new. Many other flamenco soloists emerged following the same model, with minor variations. The way of presenting the recital may have imitated the classical guitar style to a degree, but the major difference was that the flamenco guitarists were playing flamenco, not classical guitar repertoire. This means that the guitar had to imitate the flamenco singing, the dance, and musical interludes. The solo flamenco guitar recital, and each particular flamenco piece, had to be a microcosm of the flamenco mind, of the flamenco world.

Classical guitar pieces of the 19th and most of the 20th Century were composed according to the rules of Western classical music. A sonata by Fernando Sor, for example, basically follows the same structure of A-B-A (Exposition-Development-Recapitulation) that a Haydn or Mozart sonata does. A flamenco piece, in contrast, is made up of the individual musical falsetas, arranged in some kind of linear fashion, mixed with the characteristic rasgueados, or strumming patterns. These falsetas and rasgueados are all rhythmically and harmonically related to the piece, and most flamenco solo pieces follow the cante or dance form upon which they are based. In other words, a buleria or an alegria should sound like the cante or baile of a buleria or an alegria. To the classically trained, non-flamenco ear, the piece might

appear to be A-B-C-D-E... and seem to be rather unstructured. In fact, it is following a precise flamenco structure, and a flamenco-trained ear hears it clearly because a well-trained flamenco ear understands the cante or baile form on which it is based. It must also be emphasized here that the professional flamenco guitarists create their own falsetas; that is, they compose or innovate musical passages for themselves to play. This is why every competent guitarist has his own soleares, for example, which is musically different from every other guitarist's soleares. It is built on different falsetas and sequences.

The famous classical guitarists in the 19th Century may have written music for themselves, but much of it was intended for an admiring guitar public to play. Many of today's classical guitarists have works commissioned for themselves to play, but the pieces also can also become available for the guitar playing public. Classical music is almost always composed for other musicians to play, note for note, according to the written score. This cannot be stressed enough, and marks a major difference between the flamenco and classical worlds.

The Flamenco Concertos The flamenco world has had other flirtations with the classical guitar world. Classical guitar concertos have always been pretty popular, so the concert flamenco guitarists began to experiment with flamenco guitar concertos. These were not of the same structure as the most popular classical guitar concertos, like Rodrigo's Concerto de Aranjuez or or any of Giuliani's concertos. Most classical guitar concertos tend to be based on a basic classical era style. In other words, a three movement concerto, in basic sonata form. 6 (Today there are exceptions, of course, such as Rodrigo's Concierto Madrigal.)

The flamenco concertos tended to be four movement forms, with each movement based on one of the 20 or so flamenco styles. For example, Sabicas's falsetas were orchestrated into his first concerto by Moreno-Torroba, and included an alegria, a fandango, a solea por buleria and a buleria. 7 His second concerto was orchestrated by Cofiner and included a guajira, a soleares, a rondea, and his famous zapateado en re. 8 Several other flamenco guitarists had their own concertos, including Carlos Montoya and Mario Escudero.

A problem occurred with most of these early concertos. Most of them were written around pre-existing falsetas composed in a flamenco context by the guitarists themselves. The orchestrations, however, often cut the original flamenco music into pieces, inserting orchestral embellishments in a tutti fashion. That is, soloist plays, orchestra plays, etc. Such orchestrations all too often dilute the potency of the original flamenco music. Flamenco music, as we have been discovering, requires the context of cante and baile in order to be understood. These concertos have not done an adequate job of having the orchestra play the role of singer or dancer. They simply provide an abstract orchestral accompaniment

to the guitar. A new generation of flamenco guitarists is still experimenting with classical orchestrations, but fortunately, these contemporary guitarists tend to have a better understanding of classical and modern harmonies than their predecessors did, and they are often part of the composing process. An example of this new breed is flamenco guitarist Manolo Sanlucar, who wrote a guitar-orchestral work called Aljibe. 9 Because this flamenco maestro took the time to formally study orchestral composition, he was able to create a work that better blends the classical and flamenco worlds.

Flamenco Finds its Soul Mate Flamencos are always experimenting, looking for new ways of expressing flamenco. Flamenco has always grown by absorbing music from other cultures, assimilating what works and discarding what doesn't. So while they were playing flamenco concertos with orchestras, many flamenco guitarists were also forming flamenco companies and ensembles incorporating jazz musicians, world music musicians, and percussionists of all musical styles. Tomatito and Paco de Lucia began using jazz saxophonist Jorge Pardo and electric bassist Carles Benavent in their groups. Actually, this is not so revolutionary Sabicas recorded with jazz saxophonist in the 30's and a rock group in the 70's, 10 and Carlos Montoya recorded with a jazz combo in the late 50's. 11 Paco de Lucia worked with jazz guitarists John McLaughlin, Al DiMeola, and Larry Coryell, absorbing jazz's particular approach to improvistaion. His original flamenco sextet, with Pardo, Benavent, percussionist Rubem Dantas, and brothers Pepe de Lucia and Ramn de Algeciras, debuted in the 80s and forever changed the performing style of flamenco. 12 Many traditional flamencos, brought up on the classical model of guitar recital presentation, thought Paco had left the field, becoming commercialized and turning 'jazz.' In reality, only the presentation style of the music was from jazz. The way the jazz musicians could interact with the flamenco musicians with spontaneity and real punch was due to the fact that both traditions were based on this spontaneity and improvisational style. Paco was not the only one to reach this conclusion. Manolo Sanlucar released his album Flamenco Fantasy in Jazz at about the same time. 13 These experiments, in which flamencos discovered that jazz musicians had an affinity for flamenco, and vice versa, opened the door to a revolution in which the jazz presentation model of recital presentation has been added to the traditional guitar recital format. The results of this shift are several and important. First, is the inclusion of additional instrumentation into a flamenco guitar concert. Most of the top concert and recording flamenco guitarists seldom play solo guitar, Segovia/Sabicas - style, any more. The recital will include one or more guitars, flamenco singers, and possibly a flute, violin, string bass or electric bass, and lots of percussion. The music performed will always be based on the lead guitarist's material, original or arranged. Sometimes a dancer may double as a percussionist. Second, some of the contemporary recitals will arrange the music to include an improvisatory section, as jazz groups do, where the lead is passed around to the various other instrumentalists in the ensemble. In this kind of presentation, a theme may be first introduced by the guitarist, and then picked up by the flautist or violinist, backed up by the guitar and percussion. Third, if there is a guitar solo, it is included as part of the overall ensemble setting. These trends do not mean that solo recitals never happen today, but only that there are now formats available other than

the one-man show. One of the notable performances of the XIII Sevilla Biennal was Gerardo Nez performing a 1 hour solo recital, which was seen as a departure from the now normal ensemble recital. 14

None of this is to imply that flamencos are now playing jazz. What contemporary flamencos still play is flamenco, based on the same cante, the same baile, and the same rhythms that 19th and 20th Century flamencos played. But the music has been enriched by the addition of harmonies borrowed from jazz, classical music, and all forms of world music. The music need not be written down in classical guitar notation, as it would be if classically trained musicians were involved. The written page can be a real hindrance for the flamenco improviser!

Conclusion The classical guitar world is a historical development that grew out of the courts, the aristocracy, and the patronage of the rich. It's reliance on standard written notation for its musical memory made it ideal for being taught in music schools and conservatories. Flamenco developed, most-likely, out of street music, only much later, becoming a 'school' of the guitar. However, even today, the flamenco school is found not in conservatories, but in flamenco dance academies and other flamenco gatherings, and learning to accompany a dancer or singer has little to do with written guitar music. The most important thing for the classical guitarist to understand about flamenco guitarists is that flamencos are not trying to be classical guitarists. The flamenco and classical minds can understand each other only if each makes a sincere effort to enter and understand the other's world. This requires effort and a willingness to give up one's preconceptions.

The flamenco guitar performance today is bigger than the soloist, because flamenco is bigger than the guitar. The flamenco guitarist thinks in terms of cante, baile, percussion, and guitar. The flamenco presentaion format which is fast becoming standard in contemporary flamenco, at least among the top artists, is the ensemble, patterned on the jazz improvisational model. But don't let the flamenco violinist and flamenco flautist up there next to the traditional singers, dancers, and guitarists fool you. Listen carefully and you'll still hear the echos of the Middle Eastern oud, the Egyptian n flute, and the chant from the minaret.

Author's Bio Valdemar Phoenix has devoted his life to the world of flamenco. He has appeared at major festivals, college campuses, schools and arts events. He is on the touring roster of the Texas Comission on the Arts and the Mid America Arts Alliance. He performs frequently with his wife Lucia and their flamenco

conmpany Gitaneras. He has also served on the music faculty of the University of Houston-Downtown teaching the History of the Guitar.

End Notes 1. Frederic V. Grunfeld, V., The Art and Times of the Guitar (New York, Collier Books, 1969), 217 2. Grunfeld, 174-182 3. Brun, Richard H., 1997. Cultural Origins of the Modern Guitar, Soundboard, Vol. XXIV #2 Fall, 9-20 4. Brun, Richard H., 1990. Andalusia and the Modern Guitar. American Luthier, Number 22, Summer 1990, 10-14 5. Alberto Garca Reyes. (Seville, November 2002) Rafael Marn, the guitarist and theorist who never was (or so some wished) The World Wide Web: http://www.flamenco-world.com/magazine/about/rafaelmarin/marin.htm (October 5, 2004) 6. Alan Winold, Elements of Musical Understanding, (Englewood Cliffs, NJ Prentice Hall, 1966), 245 7. Sabicas/Moreno-Torroba, Concierto en Flamenco for Guitar and Orchestra, LP Decca DL 710-057 8. Sabicas/Cofiner, Concierto Gitano, VHS Private Collection, unpublished, performed by Rafael Riqueni 9. Manolo Sanlucar, Aljibe- Sinfonia Andaluz, Cassette, ASPA A1AM0101, 1992 10. Sabicas, Rock Encounter, Polydor, LP, 24-4026 11. Carlos Montoya, From St. Louis to Seville, LP, RCA LPM/LSP-1986, 1959 12. D. E. Pohren, Paco de Lucia and Family: The Master Plan (Spain) The Society for Spanish Studies 1992, 84-86 13. Manolo Sanlucar, Flamenco Fantasy in Jazz, LP, Peters International PLD 2001, 1975 14. Sylvia Calado, (Sevilla, September 17, 2004) Gerardo Nez's Exploit. The World Wide Web: http://www.flamencoworld.com/magazine/about/bienal2004/resenas/18092004/gerardo18092004.htm (October 5, 2004)

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The Armed Forces Radio Service - 0 PDFDocument11 pagesThe Armed Forces Radio Service - 0 PDFAriel_BarbanenteNo ratings yet

- Mozart225 Presseinfo PDFDocument19 pagesMozart225 Presseinfo PDFAriel_Barbanente0% (1)

- Hess 2001 7Document4 pagesHess 2001 7Ariel_BarbanenteNo ratings yet

- SigrysDocument23 pagesSigrysAriel_BarbanenteNo ratings yet

- Bill Evans DVD Collection Features Rare PerformancesDocument4 pagesBill Evans DVD Collection Features Rare PerformancesAriel_BarbanenteNo ratings yet

- Mehran Feb 2011Document1 pageMehran Feb 2011Ariel_BarbanenteNo ratings yet

- Uncut SwanSongDocument10 pagesUncut SwanSongAriel_BarbanenteNo ratings yet

- Conversation With Stefan Kudelski: John Rice, Videography, September 1985Document8 pagesConversation With Stefan Kudelski: John Rice, Videography, September 1985Ariel_BarbanenteNo ratings yet

- Katherine Butler 1Document3 pagesKatherine Butler 1Ariel_BarbanenteNo ratings yet

- Hand Injuries DPS L L v2Document3 pagesHand Injuries DPS L L v2Ariel_Barbanente100% (1)

- The Flamenco Guitar Lesson 1: by "Flamenco Chuck" KeyserDocument34 pagesThe Flamenco Guitar Lesson 1: by "Flamenco Chuck" KeyserAriel_BarbanenteNo ratings yet

- Diego y Paco Del Gastor FalsetasDocument36 pagesDiego y Paco Del Gastor FalsetasJavier Carmona100% (1)

- The Well-Formed FalsetaDocument2 pagesThe Well-Formed FalsetaAriel_BarbanenteNo ratings yet

- The Flamenco KitDocument3 pagesThe Flamenco KitAriel_BarbanenteNo ratings yet

- Flamenco and JazzDocument2 pagesFlamenco and JazzAriel_BarbanenteNo ratings yet

- Flamenco Puro, DissertationDocument75 pagesFlamenco Puro, DissertationAriel_BarbanenteNo ratings yet

- Flamenco Not NouveauDocument2 pagesFlamenco Not NouveauAriel_BarbanenteNo ratings yet

- Essential Flamenco Recordings CD BookletDocument0 pagesEssential Flamenco Recordings CD BookletAriel_BarbanenteNo ratings yet

- Art of PP CD BookletDocument0 pagesArt of PP CD BookletAriel_BarbanenteNo ratings yet

- Ricardo & Montoya BookletDocument0 pagesRicardo & Montoya BookletAriel_BarbanenteNo ratings yet

- HCR 2012Document34 pagesHCR 2012Ariel_Barbanente50% (2)

- William SavoryDocument2 pagesWilliam SavoryAriel_BarbanenteNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Over The Rainbow Wonderful World On Ukulele by Israël K. - UkuTabsDocument1 pageOver The Rainbow Wonderful World On Ukulele by Israël K. - UkuTabslepaulzNo ratings yet

- Regra Três GradeDocument9 pagesRegra Três GradeFernando CésarNo ratings yet

- Chopper Controlled DC DrivesDocument6 pagesChopper Controlled DC DrivesKalum ChandraNo ratings yet

- An Apology For PoetryDocument47 pagesAn Apology For PoetryJerald Sagaya NathanNo ratings yet

- Keyboard PhysicsDocument10 pagesKeyboard PhysicsJemuelVillonNo ratings yet

- Vertical Movement: Part Oì. (E - Leít ÏfandDocument20 pagesVertical Movement: Part Oì. (E - Leít Ïfanddricosta81No ratings yet

- Eng Communicative PaperDocument3 pagesEng Communicative PaperRoja SankarNo ratings yet

- FTTH BookDocument197 pagesFTTH BookPrashant Agarwal100% (5)

- Can't H Elp Falling in Love Alto SaxDocument2 pagesCan't H Elp Falling in Love Alto SaxJillian HonorofNo ratings yet

- Survey Kebutuhan PLC SMART SDH (1-65)Document77 pagesSurvey Kebutuhan PLC SMART SDH (1-65)ichbineinmusikantNo ratings yet

- TOA 300 - 380sdDocument2 pagesTOA 300 - 380sdStephen_Pratt_868No ratings yet

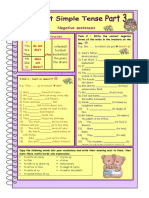

- Present Simple Tense Negative Sentences 3 Pages 6 Different Tasks With Key With Vocabulary CornerDocument5 pagesPresent Simple Tense Negative Sentences 3 Pages 6 Different Tasks With Key With Vocabulary CornerDina Ines Estupiñan SolanoNo ratings yet

- Bonnie TylerDocument7 pagesBonnie TylerRinaldo TravagliniNo ratings yet

- Shostakovich Waltz No. 2 From Suite for Variety OrchestraDocument4 pagesShostakovich Waltz No. 2 From Suite for Variety OrchestraAnonymous vrUXGCQnECNo ratings yet

- Panasonic Th-37pv80pa Th-37px80ba Th-37px80ea Th-42pv80pa Th-42px80ba Th-42px80ea Chassis Gph11deDocument175 pagesPanasonic Th-37pv80pa Th-37px80ba Th-37px80ea Th-42pv80pa Th-42px80ba Th-42px80ea Chassis Gph11depagy snvNo ratings yet

- Musical FormsDocument11 pagesMusical FormsEljay FloresNo ratings yet

- Avalon Hill Squad Leader Scenario 11Document1 pageAvalon Hill Squad Leader Scenario 11GianfrancoNo ratings yet

- S-Wave U-65-18DV10-B4 - DEDocument2 pagesS-Wave U-65-18DV10-B4 - DENymiterNo ratings yet

- Attenuator Convection Cooled DSDocument4 pagesAttenuator Convection Cooled DShennrynsNo ratings yet

- Teletronix Model LA-2A Leveling AmplifierDocument10 pagesTeletronix Model LA-2A Leveling AmplifierYannisNo ratings yet

- Eduqas Ko AfricaDocument1 pageEduqas Ko AfricaJ FrancisNo ratings yet

- Silicon Transistor: Data SheetDocument5 pagesSilicon Transistor: Data SheetAbolfazl Yousef ZamanianNo ratings yet

- I Miss You Transcription (Tabs)Document2 pagesI Miss You Transcription (Tabs)Michael LengNo ratings yet

- Phonetics and Phonology III Class NotesDocument34 pagesPhonetics and Phonology III Class NotesHà Thu BùiNo ratings yet

- HUC6800+ and HUC6800+C Broadcast Upconverters: Installation and Operation ManualDocument84 pagesHUC6800+ and HUC6800+C Broadcast Upconverters: Installation and Operation ManualTechne PhobosNo ratings yet

- Sony A900 BrochureDocument16 pagesSony A900 BrochureJose GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Research KpopDocument8 pagesResearch KpopThalia Rhine AberteNo ratings yet

- InfographicDocument1 pageInfographicCara SiliakusNo ratings yet

- Future Continuous TenseDocument17 pagesFuture Continuous TensechangNo ratings yet

- Marc Mcafee CNN Resume 2015Document1 pageMarc Mcafee CNN Resume 2015api-278018754No ratings yet