Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sales Case Digest

Uploaded by

attycertfiedpublicaccountantOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sales Case Digest

Uploaded by

attycertfiedpublicaccountantCopyright:

Available Formats

G.R. No.

L-10141

January 31, 1958

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES, petitioner, vs. PHILIPPINE RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION and the COURT OF APPEALS, respondents FACTS: MacarioApostol, allegedly acting for the Philippine Resources Development Corp. (PRDC), contracted with the Bureau of Prison for the purchase of 100 tons of designated logs, but only a small payment of the purchase price was made. In lieu of the balance of the purchase price, he caused to be delivered goods of the PRDC to the Bureau of Prison as payment for the outstanding price. The Government asserted that the subject matter of its litiga tion with Apostol was a sum of money allegedly due to the Bureau of Prison from Apostol and not the goods reportedly turned over by Apostol in payment of his private debt to the Bureau of Prison and the recovery of which was sought by PRDC; and for this reason, PRDC had no legal interest in the very subject matter in litigation as to entitle it to intervene. The Government argued that the goods which belonged to PRDC were not connected with the sale because Price ... is always paid in terms of money and the supposed payment being in kind, it is no payment at all

ISSUE: Whether PRDC had the right to intervene in the sales transaction executed between Apostol and the Bureau of Prisons and in the suit brought by the Government to enforce such sale.

HELD: The Court held that the Governments contentions were untenable, ruling that Article 1458 provides that the purchaser may pay a price certain in money or its equivalent, which means payment of the price need not be in

money. Whether the goods claimed by PRDC belong to it and delivered to the Bureau of Prison by Apostol in payment of his account is sufcient payment therefor, is for the court to pass upon and decide after hearing all the parties in the case. PRDC therefore had a positive right to intervene in the case because should the trial court credit Apostol with the value price of the materials delivered by him, certainly PRDC would be affected adversely if its claim of ownership to such goods were upheld. Republic is not at all authority to say that under Article 1458, as it de nes a contract of sale, the term equivalent of price can cover other than money or other media of exchange, since Republic covers not the perfection stage of a contract of sale, but rather the consummation stage where the price agreed upon (which ideally should be in money or its equivalent) can be paid under the mutual arrangements agreed upon by the parties to the contract of sale, even by dation in payment, as was the case in Republic.

MUNICIPALITY OF VICTORIAS, petitioner, vs. THE COURT OF APPEALS, NORMA LEUENBERGER and FRANCISCO SOLIVA, respondents.

G.R. No. L-31189 March 31, 1987

FACTS: Respondent Norma Leuenberger, married to Francisco Soliva, inherited the whole of Lot No. 140 from her grandmother, Simeona J. Vda. de Ditching (not from her predeceased mother Isabel Ditching). In 1952, she donated a portion of Lot No. 140, about 3 ha., to the municipality for the ground of a certain high school and had 4 ha. converted into a subdivision. (TSN, July 1, 1964, p. 24).

In 1963, she had the remaining 21 ha. or 208.157 sq. m. relocated by a surveyor upon request of lessee Ramon Jover who complained of being prohibited by municipal officials from cultivating the land. It was then that she discovered that the parcel of land, more or less 4 ha. or 33,747 sq.m. used by Petitioner Municipality of Victorias, as a cemetery from 1934, is within her property which is now Identified as Lot 76 and covered by TCT No. 34546. On January 11, 1964, Respondents filed a complaint in the Court of First Instance of Negros Occidental, Branch 1, for recovery of possession of the parcel of land occupied by the municipal cemetery (Record on Appeal, p. 1). In its answer, petitioner Municipality, by way of special defense, alleged ownership of the lot, subject of the complaint, having bought it from Simeona Jingco Vda. de Ditching sometime in 1934 (Record on Appeal, p. 7). The lower court decided in favor of the Municipality. On appeal Respondent appellate Court set aside the decision of the lower court (Record on AppeaL p. 9); hence, this petition for review on certiorari.

ISSUE: WON the evidence presented by the petitioner municipality is sufficient to substantiate its claim that it acquired the disputed land by means of a Deed of Sale.

HELD:

The court held that testimonies and documentary evidence presented sufficiently identify the land sold by the predecessors-in-interest of private respondent. To insist on the technical description of the land in dispute would be to sacrifice substance to form which would undoubtedly result in manifest injustice to the petitioner.

Moreover, it is expressly provided by law that the thing sold shall be understood as delivered, when it is placed in the control and possession of the

vendee. (Civil Code Art. 1497). Where there is no express provision that title shall not pass until payment of the price, and the thing gold has been delivered, title passes from the moment the thing sold is placed in the possession and control of the buyer. (Kuenzle & Streiff vs. Watson & Co., 13 PhiL 26 [1909]). Delivery produces its natural effects in law, the principal and most important of which being the conveyance of ownership, without prejudice to the right of the vendor to payment of the price. (Ocejo, Perez & Co. vs. International Banking Corp., 37 PhiL 631 [1918]).

Similarly, when the sale is made through a public instrument, the execution thereof shall be equivalent to the delivery of the thing which is the object of the contract, if from the deed, the contrary does not appear or cannot be clearly inferred. (Civil Code Art. 1498). The execution of the public instrument operates as a formal or symbolic delivery of the property sold and authorizes the buyer to use the document as proof of ownership. (Florendo v. Foz, 20 PhiL 388 [1911]).

In the case at bar it is undisputed that petitioner had been in open, public, adverse and continuous possession of the land for a period of more than thirty years. In fact, according to the municipal treasurer there are over 1000 graves in the cemetery.

Delta Motors Sales vs. Niu Kim Duan G.R. No. 61043. September 2, 1992.] Facts: On 5 July 1975, Niu Kim Duan and Chan Fue Eng (defendants) purchased from Delta Motor Sales

Corporation 3 units of DAIKIN air-conditioner all valued at P19,350.00. The deed of sale stipulates that the defendants shall pay a down payment of P774.00 and the balance of P18,576.00 shall be paid by them in 24 installments ; that the title to the properties purchased shall remain with Delta Motors until the purchase price thereof is fully paid; that if any two installments are not paid by the defendants on their due dates, the whole of the principal sum remaining unpaid shall become due, with interest However, after paying the amount of P6,966.00, the defendants failed to pay at least 2 monthly installments. s of 6 January 1977, the remaining unpaid obligation of the defendants amounted to P12,920.08. Statements of accounts were sent to the defendants and the Delta Motors collectors personally went to the former to effect collections but they failed to do so. Because of the unjustified refusal of the defendants to pay their outstanding account and their wrongful detention of the properties in question, Delta Motors tried to recover the said properties extra-judicially but it failed to do so. The matter was later referred by Delta Motors to its legal counsel for legal action. In its verified complaint dated 28 January 1977, Delta Motors prayed for the issuance of a writ of replevin, which the Court granted in its Order dated 28 February 1977, after Delta Motors posted the requisite bond. On 11 April 1977, Delta Motors, by virtue of the writ, succeeded in retrieving the properties in question. The trial court promulgated its decision on 11 October 1977 ordering the defendants to pay Delta Motors the amount of P6,188.29 with a 14% per annum interest which was due on the 3 Daikin airconditioners the defendants purchased from Delta Motors under a Deed of Conditional Sale, after the same was declared rescinded by the trial court. They were likewise ordered to pay Delta Motors P1,000.00 for and as attorneys fees.

ISSUE: WON the lower court erred in its decision to order the defendants to pay the unpaid balance despite the fact that Delta motors already retrieved the subject properties.

HELD: The court held that remedies available to vendor in a sale of personal property payable in installments The vendor in a sale of personal property payable in installments may exercise one of three remedies, namely, (1) exact the fulfillment of the obligation, should the vendee fail to pay; (2) cancel the sale upon the vendees failure to pay two or more installments; (3) foreclose the chattel mortgage, if one has been constituted on the property sold, upon the vendees failure to pay two or more installments. The third option or remedy, however, is subject to the limitation that the vendor cannot recover any unpaid balance of the price and any agreement to the contrary is void (Art. 1484). Moreover, the 3 remedies are alternative and NOT cumulative. If the creditor chooses one remedy, he cannot avail himself of the other two. Thus in the case at bar, Air-conditioning units repossessed, bars action to exact payment for balance of the price Delta Motors had taken possession of the 3 air-conditioners, through a writ of replevin when defendants refused to extra-judicially surrender the same. The case Delta Motors filed was to seek a judicial declaration that it had validly rescinded the Deed of Conditional Sale. Delta Motors thus chose the second remedy of Article 1484 in seeking enforcement of its contract with defendants. Having done so, it is barred from exacting payment from defendants of the balance of the price of the three airconditioning units which it had already repossessed. It cannot have its cake and eat it too.

G.R. No. 119745 June 20, 1997

POWER COMMERCIAL AND INDUSTRIAL CORPORATION, petitioner, vs. COURT OF APPEALS, SPOUSES REYNALDO and ANGELITA R. QUIAMBAO and PHILIPPINE NATIONAL BANK, respondents.

FACTS: Petitioner Power Commercial & Industrial Development Corporation entered into a contract of sale involving a 612-sq. m. parcel of land with the spouses Reynaldo and Angelita R. Quiambao, herein private respondents. The parties agreed that petitioner would pay private respondents P108,000.00 as down payment, and the balance of P295,000.00 upon the execution of the deed of transfer of the title over the property. Further, petitioner assumed, as part of the purchase price, the existing mortgage on the land. In full satisfaction thereof, he paid P79,145.77 to respondent Philippine National Bank (PNB for brevity).

On June 1, 1979, respondent spouses mortgaged again said land to PNB to guarantee a loan of P145,000.00, P80,000.00 of which was paid to respondent spouses. Petitioner agreed to assume payment of the loan. On February 15,

1980, PNB informed respondent spouses that, for petitioners failure to submit the papers necessary for approval pursuant to the formers letter dated January 15, 1980, the application for assumption of mortgage was considered withdrawn.

On February 19, 1982, PNB sent petitioner informing him that the loan has been past due from last maturity with interest arrearages amounting to P25,826.08 as of February 19, 1982. PNB further requested petitioner to remit payments to cover interest, charges, and at least part of the principal.

On March 17, 1982, petitioner filed Civil Case No. 45217 against respondent spouses for rescission and damages before the Regional Trial Court of Pasig, Branch 159. Then, in its reply to PNBs letter of February 19, 1982, petitioner demanded the return of the payments it made on the ground that its assumption of mortgage was never approved. On May 31, 1983, while this case was pending, the mortgage was foreclosed. The property was subsequently bought by PNB during the public auction.

On July 12, 1990, the trial court ruled that the failure of respondent spouses to deliver actual possession to petitioner entitled the latter to rescind the sale, and in view of such failure and of the denial of the latters assumption of mortgage, PNB was obliged to return the payments made by the latter. On appeal by respondent-spouses and PNB, Respondent Court of Appeals reversed the trial court.

ISSUES 1. Whether or not there was a substantial breach of the contract between the parties warranting rescission 2. Whether or not there was a mistake in payment made by petitioner, obligating PNB to return such payments.

HELD 1. The alleged failure of respondent spouses to eject the lessees from the lot in question and to deliver actual and physical possession thereof cannot be considered a substantial breach of a condition for two reasons: first, such failure was not stipulated as a condition whether resolutory or suspensive in the contract; and second, its effects and consequences were not specified either. If the parties intended to impose on respondent spouses the obligation to eject the tenants from the lot sold, it should have included in the contract a provision similar to that referred to in Romero vs. Court of Appeals, where the ejectment of the occupants of the lot sold by private respondent was the operative act which set into motion the period of petitioners compliance with his own obligation.

As stated, the provision adverted to in the contract pertains to the usual warranty against eviction, and not to a condition that was not met. The terms of the contract are so clear as to leave no room for any other interpretation.

2. Contrary to the contention of petitioner that a return of the payments it made to PNB is warranted under Article 2154 of the Code, solutio indebiti does not apply in this case. This doctrine applies where: (1) a payment is made when there exists no binding relation between the payor, who has no duty to pay, and the person who received the payment, and (2) the payment is made through mistake, and not through liberality or some other cause.

In this case, petitioner was under obligation to pay the amortizations on the mortgage under the contract of sale and the deed of real estate mortgage. Under the deed of sale, both parties agreed to abide by any and all the requirements of PNB in connection with the real estate mortgage. Petitioner was aware that the deed of mortgage made it solidarily and, therefore, primarily liable for the mortgage obligation. Therefore, it cannot be said that it did not have a duty to pay to PNB the amortization on the mortgage.

Also, petitioner insists that its payment of the amortization was a mistake because PNB disapproved its assumption of mortgage after it failed to submit the necessary papers for the approval of such assumption. But even if petitioner was a third party in regard to the mortgage of the land purchased, the payment of the loan by petitioner was a condition clearly imposed by the contract of sale. This fact alone disproves petitioners insistence that there was a mistake in payment. On the contrary, such payments were necessary to protect its interest as a the buyer(s) and new owner(s) of the lot.

GERARDA A. DIZON-ABILLA and the HEIRS OF RONALDO P. ABILLA v. SPS. CARLOS AND THERESITA GOBONSENG 577 SCRA 401 (2009 FACTS: Gerarda A. Dizon-Abilla and the Heirs of Ronaldo P. Abilla extended to Spouses Carlos and Theresita Gobonseng a loan in the amount of Five Hundred Fifty Thousand Pesos (P550, 000.00). Spouses Gobonseng, however, failed to settle the same. They then executed a Deed of Sale covering Seventeen (17) lots in favor of Dizon-Abilla and Heirs of Abilla. The Deed provides an option to buy the lots within six (6) months in favor of Spouses Gobonseng which they failed to exercise. Dizon-Abilla and Heir of Abilla filed a case of specific performance and damages for the expenses attendant to the Preparation and Registration of the Deed of Sale. The RTC of Dumaguete City ruled the option to buy was null and void. On appeal, the Court of Appeals affirmed the trial courts decision. Nineteen (19) days after the decision of the CA became final, an Urgent Motion to Repurchase was filed to the trial court by Spouses Gobonseng alleging that they made a tender of payment to RCBC Dumaguete Branch, but was denied. The case was raffled to a new judge which ordered the release of the deposited money as payment for the repurchase. DizonAbilla and Heirs of Abilla filed a Petition for Review on Certiorari challenging the trial courts decision allowing Spouses Gobonsengs repurchase. The Supreme Court denied their petition. Dizon-Abilla and Heirs of Abilla subsequently filed another case to the trial court asserting that they are entitled to 2% monthly interest. The trial court ruled in favor of Spouses Gobonseng which was affirmed by the CA. The appellate court ruled that the case has already been closed and terminated.

ISSUE: Whether or not the Court of Appeals erred in its decision to consider the case closed and terminated HELD: The amount tendered by Spouses Domonseng, the correctness of which had already been passed upon by the appellate court, has been determined with finality. Every litigation must necessarily come to an end. Access to courts is guaranteed, but once a litigants right has been adjudicated in a valid final judgment of a competent court, he should not be granted an unbridled license to go back for another try. The prevailing party should not be harassed by subsequent suits. For, if endless litigations were to be encouraged, unscrupulous litigations would multiply in number to the detriment of the administration of justice.

SORIANO V. BAUTISTA 6 SCRA 946 (1962) FACTS: Spouses Bautista are the absolute and registered owners of a parcel of land. In May 30, 1956, the said spouses entered into an agreement entitled Kasulatan ng Sanglaan (mortgage) in favor of spouses Soriano for the amount of P1,800. Simultaneously with the signing of the deed, the spouses Bautista transferred the possession of the subject property to spouses Soriano. The spouses Soriano have, since that date, been in possession of the property and are still enjoying the produce thereof to the exclusion of all other persons 1. Sometime after May 1956, the spouses Bautista received from spouses Soriano the sum of P450 pursuant to the conditions agreed upon in the document. However, no receipt was issued. The said amount was returned by the spouses Bautista 2. In May 13, 1958, a certain Atty. Ver informed the spouses Bautista that the spouses Soriano have decided to purchase the subject property pursuant to par. 5 of the document which states that the mortgagees may purchase the said land absolutely within the 2-year term of the mortgage for P3,900. 3. Despite the receipt of the letter, the spouses Bautista refused to comply with Sorianos demand

4. As such, spouses Soriano filed a case, praying that they be allowed to consign or deposit with the Clerk of Court the sum of P1,650 as the balance of the purchase price of the land in question 5. The trial court held in favor of Soriano and ordered Bautista to execute a deed of absolute sale over the said property in favor of Soriano. 6. Subsequently spouses Bautista filed a case against Soriano, asking the court to order Soriano to accept the payment of the principal obligation and release the mortgage and to make an accounting the harvest for the 2 harvest seasons (1956-1957). 7. CFI held in Sorianos favor and ordered the execution of the deed of sale in their favor 8. Bautista argued that as mortgagors, they cannot be deprived of the right to redeem the mortgaged property, as such right is inherent in and inseparable from a mortgage.

ISSUE: WON spouses Bautista are entitled to redemption of subject property

HELD: No. While the transaction is undoubtedly a mortgage and contains the customary stipulation concerning redemption, it carries the added special provision which renders the mortgagors right to redeem defeasible at the election of the mortgagees. There is nothing illegal or immoral in this as this is allowed under Art 1479 NCC which states: A promise to buy and sell a determinate thing for a price certain is reciprocally demandable. An accepted unilateral promise to buy or to sell a determinate thing for a price certain is binding upon the promissor if the promise supported by a consideration apart from the price.

In the case at bar, the mortgagors promise is supported by the same consideration as that of the mortgage itself, which is distinct from the consideration in sale should the option be exercised. The mortgagors promise was in the nature of a continuing offer, non-withdrawable during a period of 2

years, which upon acceptance by the mortgagees gave rise to a perfected contract of sale.

Furthermore, the tender of P1,800 to redeem the mortgage by spouses Bautista was ineffective for the purpose intended. Such tender must have been made after the option to purchase had been exercised by spouses Soriano. Bautistas offer to redeem could be defeated by Sorianos preemptive right to purchase within the period of 2 years from May 30, 1956. Such right was availed of and spouses Bautista were accordingly notified by Soriano. Offer and acceptance converged and gave rise to a perfected and binding contract of purchase and sale.

You might also like

- Manual For ProsecutorsDocument51 pagesManual For ProsecutorsArchie Tonog0% (1)

- Recruitment and Selection of Life Insurance AgentDocument80 pagesRecruitment and Selection of Life Insurance AgentHirak SinhaNo ratings yet

- Banking Law AssignmentDocument11 pagesBanking Law AssignmentTanu Shree SinghNo ratings yet

- Image PDFDocument11 pagesImage PDFRoselle MalabananNo ratings yet

- Article 1355Document22 pagesArticle 1355DexterJohnN.BambalanNo ratings yet

- 4 Manresa Labor TranscriptionDocument30 pages4 Manresa Labor TranscriptionattycertfiedpublicaccountantNo ratings yet

- Cases in Sales 69-71Document6 pagesCases in Sales 69-71emyNo ratings yet

- Agency 1919-1932 PDFDocument9 pagesAgency 1919-1932 PDFPia SottoNo ratings yet

- Sales CasesDocument33 pagesSales CasesTNVTRL100% (1)

- 163362Document14 pages163362Robelen Callanta100% (1)

- Case AnalysisDocument5 pagesCase AnalysisrhobiecorboNo ratings yet

- Sa2 Pu 14 PDFDocument150 pagesSa2 Pu 14 PDFPolelarNo ratings yet

- Arbitration Law Midterms JurisprudenceDocument9 pagesArbitration Law Midterms JurisprudenceGanielaNo ratings yet

- Zimbabwe: From Hyperinflation To Growth, Cato Development Policy Analysis No. 6Document36 pagesZimbabwe: From Hyperinflation To Growth, Cato Development Policy Analysis No. 6Cato Institute100% (3)

- DBP Vs DoyonDocument5 pagesDBP Vs DoyonMelody Lim DayagNo ratings yet

- Bank of America v. American RealtyDocument3 pagesBank of America v. American RealtyMica MndzNo ratings yet

- Salvador v. RabajaDocument2 pagesSalvador v. RabajaJenin VillagraciaNo ratings yet

- 033 Primelink Vs MagatDocument1 page033 Primelink Vs MagatNichole LanuzaNo ratings yet

- NBFC1Document82 pagesNBFC1Tushar PawarNo ratings yet

- Legal MemorandumDocument5 pagesLegal MemorandumCheyanne ArguellesNo ratings yet

- SPS Villaluz Vs LandbankDocument2 pagesSPS Villaluz Vs LandbanktrextanNo ratings yet

- AZRC-ERF Fillable Application Forms (May 2017)Document5 pagesAZRC-ERF Fillable Application Forms (May 2017)Karen CraigNo ratings yet

- Sps Dato v. BPIDocument22 pagesSps Dato v. BPIColee StiflerNo ratings yet

- List CSP Bank of BarodaDocument2 pagesList CSP Bank of BarodaNisa ArunNo ratings yet

- Lajave Agricultural Management and Dev't Enterprises Inc. vs. Sps. Javellana, GR No. 223785, Nov. 7, 2018Document6 pagesLajave Agricultural Management and Dev't Enterprises Inc. vs. Sps. Javellana, GR No. 223785, Nov. 7, 2018LawrenceAltezaNo ratings yet

- Case Digests Sales Gen. Food Corp and Rudolf LietzDocument6 pagesCase Digests Sales Gen. Food Corp and Rudolf LietzLouise Nicole AlcobaNo ratings yet

- Obillos v. CIRDocument7 pagesObillos v. CIRmceline19No ratings yet

- El Banco Espanol V PetersonDocument4 pagesEl Banco Espanol V PetersongabbyborNo ratings yet

- Qua Chee Gan VDocument2 pagesQua Chee Gan VmfspongebobNo ratings yet

- Tajanglangit Vs Southern MotorsDocument2 pagesTajanglangit Vs Southern MotorsjessapuerinNo ratings yet

- Dagupan Trading Company v. MacamDocument2 pagesDagupan Trading Company v. MacamFrancisco Ashley AcedilloNo ratings yet

- Bagnas vs. CADocument1 pageBagnas vs. CAOnnie LeeNo ratings yet

- Finals Property 2018Document44 pagesFinals Property 2018Arleen Ingrid SantosNo ratings yet

- Government vs. CabangisDocument4 pagesGovernment vs. CabangisnerissatobillaNo ratings yet

- Batch 1 Herrera Vs Petro Phil Corp 146 SCRA 385Document55 pagesBatch 1 Herrera Vs Petro Phil Corp 146 SCRA 385Jc RobredilloNo ratings yet

- Addison vs. FelixDocument1 pageAddison vs. FelixMarco Miguel LozadaNo ratings yet

- Pci Leasing and Finance, Inc .V. Giraffe-XDocument12 pagesPci Leasing and Finance, Inc .V. Giraffe-XvalkyriorNo ratings yet

- Right of Accession Digest EditedDocument30 pagesRight of Accession Digest EditedEileen Eika Dela Cruz-LeeNo ratings yet

- 57-Sps. Paringit v. Bajit G.R. No. 181844 September 29, 2010Document5 pages57-Sps. Paringit v. Bajit G.R. No. 181844 September 29, 2010Jopan SJNo ratings yet

- 116 People V RTCDocument2 pages116 People V RTCKylie Kaur Manalon DadoNo ratings yet

- Sales Digest Batch 2Document6 pagesSales Digest Batch 2Joannalyn Libo-onNo ratings yet

- NGA Vs IACDocument2 pagesNGA Vs IACevadnaliorf12100% (1)

- ARCELLANA - Alcantara V Reta (2017)Document1 pageARCELLANA - Alcantara V Reta (2017)huhah303No ratings yet

- 03 Carillo vs. DabonDocument2 pages03 Carillo vs. DabonClaudine Allyson DungoNo ratings yet

- Carceller Vs CADocument2 pagesCarceller Vs CAailynvdsNo ratings yet

- Involuntary Dealings Digest LTDDocument2 pagesInvoluntary Dealings Digest LTDLei MorteraNo ratings yet

- Case Digest Banco FilipinoDocument1 pageCase Digest Banco FilipinoRogers NetiboNo ratings yet

- Legal Memorandum - Issue On RA 9997Document8 pagesLegal Memorandum - Issue On RA 9997Sylvia VillalobosNo ratings yet

- Art 1770Document2 pagesArt 1770Eileen Eika Dela Cruz-LeeNo ratings yet

- Panganiban, J.:: (G.R. No. 148267. August 8, 2002)Document6 pagesPanganiban, J.:: (G.R. No. 148267. August 8, 2002)Mary Denzyll BunalNo ratings yet

- Sancho Vs LizaragaDocument3 pagesSancho Vs LizaragajessapuerinNo ratings yet

- Carumba V CADocument2 pagesCarumba V CAABNo ratings yet

- MARIANO EstoqueDocument1 pageMARIANO EstoqueReyshanne Joy B MarquezNo ratings yet

- Augusto Benedicto Santos V Northwest Orient LinesDocument23 pagesAugusto Benedicto Santos V Northwest Orient LineskeemperworksNo ratings yet

- Floro vs. Llenado, 244 SCRA 713, G.R. No. 75723 June 2, 1995Document10 pagesFloro vs. Llenado, 244 SCRA 713, G.R. No. 75723 June 2, 1995Daysel FateNo ratings yet

- 41) Depra V DumlaoDocument1 page41) Depra V DumlaoTetel GuillermoNo ratings yet

- de Luna vs. AbrigoDocument3 pagesde Luna vs. AbrigoJohnny EnglishNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Tan Eng Kee vs. CADocument21 pagesHeirs of Tan Eng Kee vs. CAMichelle Montenegro - AraujoNo ratings yet

- 109 First Philippine International Bank v. Court of Appeals, 252 SCRA 259Document25 pages109 First Philippine International Bank v. Court of Appeals, 252 SCRA 259Ton RiveraNo ratings yet

- Harrison Vs NavarroDocument1 pageHarrison Vs NavarroCherry SormilloNo ratings yet

- Bass vs. de La Rama DigestDocument2 pagesBass vs. de La Rama Digestdexter lingbananNo ratings yet

- Alfredo Vs Borras GR No 144225Document17 pagesAlfredo Vs Borras GR No 144225SarahLeeNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Jose Lim vs. LimDocument12 pagesHeirs of Jose Lim vs. LimJerome ArañezNo ratings yet

- Republic vs. EvangelistaDocument2 pagesRepublic vs. EvangelistaGia DimayugaNo ratings yet

- Cebu Oxygen v. Bercilles 40474Document2 pagesCebu Oxygen v. Bercilles 40474Jona MayNo ratings yet

- Francisco Vs OnrubiaDocument1 pageFrancisco Vs OnrubiaBantogen BabantogenNo ratings yet

- Vs. Atlantic, Gulf and Pacific Co. (7 Phil. Rep., 359) - in CommentingDocument12 pagesVs. Atlantic, Gulf and Pacific Co. (7 Phil. Rep., 359) - in CommentingTrinNo ratings yet

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights TimelineDocument5 pagesUniversal Declaration of Human Rights TimelineNisha ArdhayaniNo ratings yet

- MMDA V Concerned Residents of Manila Bay (Environmental Law)Document16 pagesMMDA V Concerned Residents of Manila Bay (Environmental Law)OpsOlavarioNo ratings yet

- Dagupan Trading Vs MacamDocument1 pageDagupan Trading Vs MacamCharlie BartolomeNo ratings yet

- Revised Forestry Code CasesDocument67 pagesRevised Forestry Code CasesKrstn QbdNo ratings yet

- Nego ReviewerDocument11 pagesNego ReviewerattycertfiedpublicaccountantNo ratings yet

- AFfidavit of CorrectionDocument1 pageAFfidavit of CorrectionattycertfiedpublicaccountantNo ratings yet

- Hagonoy, Davao Del Sur: Danilo and Evangeline DiezDocument10 pagesHagonoy, Davao Del Sur: Danilo and Evangeline DiezattycertfiedpublicaccountantNo ratings yet

- 2 Disinterested PersonDocument1 page2 Disinterested PersonattycertfiedpublicaccountantNo ratings yet

- 2016Document2 pages2016attycertfiedpublicaccountantNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of LossDocument1 pageAffidavit of LossattycertfiedpublicaccountantNo ratings yet

- Speech Jade Debate2Document4 pagesSpeech Jade Debate2attycertfiedpublicaccountantNo ratings yet

- De Castro-Criminal LawDocument32 pagesDe Castro-Criminal LawIvan LinNo ratings yet

- TableDocument2 pagesTableattycertfiedpublicaccountantNo ratings yet

- Fists Fingers: Are We Forcing The Issue of A Philippine "National Identity"?Document17 pagesFists Fingers: Are We Forcing The Issue of A Philippine "National Identity"?attycertfiedpublicaccountantNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDocument2 pagesNew Microsoft Word DocumentattycertfiedpublicaccountantNo ratings yet

- DigestDocument2 pagesDigestattycertfiedpublicaccountantNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDocument9 pagesNew Microsoft Word DocumentattycertfiedpublicaccountantNo ratings yet

- ANnex ADocument1 pageANnex AattycertfiedpublicaccountantNo ratings yet

- Contingency Procedures For 2016 NLEDocument14 pagesContingency Procedures For 2016 NLEKris AblanNo ratings yet

- Com - Res - 10031-BEI Rules Constitution Composition AppointmentDocument7 pagesCom - Res - 10031-BEI Rules Constitution Composition AppointmentattycertfiedpublicaccountantNo ratings yet

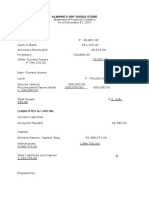

- Assets:: Almarie'S Dry Goods StoreDocument2 pagesAssets:: Almarie'S Dry Goods StoreattycertfiedpublicaccountantNo ratings yet

- Digests Part 2Document3 pagesDigests Part 2attycertfiedpublicaccountantNo ratings yet

- Exercise For Bar Prepartion Julia QuisaotDocument9 pagesExercise For Bar Prepartion Julia QuisaotattycertfiedpublicaccountantNo ratings yet

- Arbitration#Ixzz3Qoyer5Ma: @inquirerdotnet On Twitter Inquirerdotnet On FacebookDocument2 pagesArbitration#Ixzz3Qoyer5Ma: @inquirerdotnet On Twitter Inquirerdotnet On FacebookattycertfiedpublicaccountantNo ratings yet

- A C#M/G# F#M DDocument7 pagesA C#M/G# F#M DattycertfiedpublicaccountantNo ratings yet

- Lou CRIM DigestDocument2 pagesLou CRIM DigestattycertfiedpublicaccountantNo ratings yet

- De Castro-Criminal LawDocument32 pagesDe Castro-Criminal LawIvan LinNo ratings yet

- AnswerDocument3 pagesAnswerattycertfiedpublicaccountantNo ratings yet

- T or FDocument1 pageT or FattycertfiedpublicaccountantNo ratings yet

- Poli AssignmentafdsfDocument18 pagesPoli AssignmentafdsfattycertfiedpublicaccountantNo ratings yet

- Aa FDF FfffeeDocument2 pagesAa FDF FfffeeattycertfiedpublicaccountantNo ratings yet

- Justice Teresita Leonardo-De Castro Cases (2008-2015) : Scope and Limitations of Taxation (Constitutional Limitations)Document4 pagesJustice Teresita Leonardo-De Castro Cases (2008-2015) : Scope and Limitations of Taxation (Constitutional Limitations)jimNo ratings yet

- UK P2PFA 2016.09.30 - Oxera Report - The Economics of P2P LendingDocument76 pagesUK P2PFA 2016.09.30 - Oxera Report - The Economics of P2P LendingCrowdfundInsider100% (1)

- ACCT 3331 Exam 2 Review Chapter 18 - Revenue RecognitionDocument14 pagesACCT 3331 Exam 2 Review Chapter 18 - Revenue RecognitionXiaoying XuNo ratings yet

- List Analysts Attended Analyst Meet 140217Document2 pagesList Analysts Attended Analyst Meet 140217akashNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Life Insurance SectorLife Insurance CorporationDocument38 pagesAnalysis of Life Insurance SectorLife Insurance Corporationmayur9664501232No ratings yet

- RbiDocument35 pagesRbiaadishNo ratings yet

- Mohit 240221 11 55 01 001Document2 pagesMohit 240221 11 55 01 001shreya arunNo ratings yet

- Axiata Dialog 3Q09 ResultDocument6 pagesAxiata Dialog 3Q09 ResultseanreportsNo ratings yet

- Nairobi MCC 14 July 2022Document37 pagesNairobi MCC 14 July 2022kwerNo ratings yet

- RJSC Form XviiiDocument2 pagesRJSC Form XviiiMd. ZubaerNo ratings yet

- 0 0 0 125 0 125 SGST (0006)Document2 pages0 0 0 125 0 125 SGST (0006)mohammad TabishNo ratings yet

- Iaccess FAQs 02.10.2023Document17 pagesIaccess FAQs 02.10.2023pink jennieNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Adjusting Entries DDocument14 pagesIntroduction To Adjusting Entries DYuj Cuares Cervantes100% (1)

- APGVB NotificationDocument7 pagesAPGVB NotificationkdvprasadNo ratings yet

- The Conceptual Framework of Factoring On Small and Medium EnterprisesDocument6 pagesThe Conceptual Framework of Factoring On Small and Medium EnterprisesSavyasaachi ManjrekarNo ratings yet

- Security Rate For Security GuardsDocument1 pageSecurity Rate For Security GuardsengelNo ratings yet

- 12 Chapter 6Document28 pages12 Chapter 6SAMIKSHA ORASKARNo ratings yet

- CT6 QP 0416Document6 pagesCT6 QP 0416Shubham JainNo ratings yet

- Nifras CVDocument3 pagesNifras CVmamzameer7No ratings yet

- 5e1c33a30ab36 - Struktur Organisasi 2 Desember 2019 Final PDFDocument1 page5e1c33a30ab36 - Struktur Organisasi 2 Desember 2019 Final PDFAcxel AgustavoNo ratings yet

- Schedule of Charges BandhanDocument3 pagesSchedule of Charges BandhanSoumya ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Smieliauskas 6e - Solutions Manual - Chapter 01Document8 pagesSmieliauskas 6e - Solutions Manual - Chapter 01scribdteaNo ratings yet