Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Uploaded by

The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Uploaded by

The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeCopyright:

Available Formats

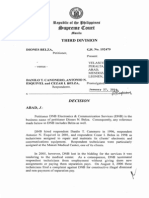

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES

SUPREME COURT

MANILA

EN BANC

GRECO ANTONIO US BEDA B. BELGIC:A,

BISHOP REUBEN M. ABANTE and

REV. JOSE L. GONZALEZ,

Petitioners,

-versus-

G.R. No.-------

PRESIDENT BENIGNO SIMEON C:. AQUINO Ill,

THE SENATE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Represented by

SENATE PRESIDENT FRANKLIN M. DRILON,

THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, Represented by

SPEAKER FELICIANO BELMONTE, JR.,

THE EXECUTIVE OFFICE, Represented by

EXECUTIVE SECRETARY PAQUITO N. OCHOA, JR.,

THE DEPARTMENT OF BUDGET AND MANAGEMENT,

Represented by SECRETARY FLORENC:IO ABAD,

THE DEPARTMENT OF FINANCE, Represented

by SECRETARY CESAR V. PUR! SIMA

and THE BUREAU OF TREASURY, Represented by

ROSALIA V. DE LEON,

Respondents.

X ------------------------------------------------------- X

PETITION

Petitioners, by counsel, respectfully state:

PREFATORY STATEMENT

3

The nation has not recovered from the shock, and

worst, the economic destitution brought about by the

plundering of the Treasury by the deposed dictator and his

cohorts. 1\ provision which allows even the sli!.':htest

possibility of a repetition of this sad experience cannot

remain written in our statute books.

1

1

Demetria vs. Alba (G.R. No. 71977; 27 February 1987).

1

The case of Demetria vs. Alba involved a sweeping grant of power

to the President to realign, not just savings, but funds within the

executive department to any programs or projects therein included in

the general appropriations act. The power of the President under the

Disbursement Acceleration Program (DAP) is almost as sweeping

involving realignment of "unobligated allotments" to any programs or

projects, even those not included in the general appropriations act and

those yet to be implemented.

Ironically, the justification for the DAP is not the bankruptcy of

government coffers but the slow spending by the Executive Department

itself; not economic destitution but the Executive's need to sustain

economic growth - all within the province of the Executive and all

within the President's power to execute. For his own failings -- because

the executive power is vested in the President of the Philippines alone--

Respondent President saw it as sufficient justification to allocate

governmental resources at his whim disregarding in the process

constitutional and statu tory limitations on the spending of public funds.

And this case does not even involve a statute but an executive

practice and policy guideline that gives the President unbridled

discretion on the expenditure of public funds.

If the Pork Barrel System, including the Priority Development

Assistance Fund (PDAF), merges the twin evils of unmitigated power

and lack of accountability "so seamlessly that both political branches are

willingly caught in its unconstitutional embrace- and neither is inclined

to break it"

2

the Disbursement Acceleration Program has

unconstitutionally redefined the functions of the political branches of

governrhent to such extent that the members of the legislatures

perforrrted and is performing executive functions and the executive has

arrogated unto itself the spending power of Congress.

In the guise of savings generated by failure to utilize appropriated

funds, or worse, by impoundment of the budget, the President has

virtually a wide latitude of discretion in expending these savings not

merely to augment "any item in the general appropriations law" but to

fund other projects not part of any item in the budget, including those

projects to be identified by legislators as exemplified by the

disbursements involving the DAP or programs or projects that have yet

to be iniplementecL

2

Petition in Belgica, et aL vs. The Honorable Executive Secretary, G.R. No. 20B566.

2

NATURE AND TIMELINESS OF THE PETITION

This is a Petition for Certiorari under Rule 65 of the Rules of Court

to annul and set aside for being unconstitutional and illegal the

Disbursement Acceleration Program (DAP) of the Respondents started

in October 2011 and continued up to the present, as governed by

National Budget Circular No. 541 dated 18 July 2012.

The DAP is a continuing program of the Respondents and the

disbursement of funds thereunder may safely be presumed in the

regular course of the business of government. Respondent President

himself has been reported to have defended the DAP and rejected calls

to scrap the program.3

Considering the continuation of the DAP, it is inevitable that

public funds will be released in accordance therewith. This

notwithstanding the unconstitutionality of the DAP and the absence of

appropriations or, in cases with existing appropriations, the Jack of

budgetary deficits to be augmented, with respect to the objects of the

expenditures under the DAP.

Petitioners are left with no other recourse except to apply to the

Honorable Court for relief in order to prevent the further illegal

disbursements of public funds that are being made pursuant to

unconstitutional measures.

PAIUIES

Petitioners GRECO ANTONIOUS BEDA B. BELGICA, Bishop

REUBEN ABANTE and Rev. JOSE L. GONZALEZ are of legal age, Filipinos

and residents of the Philippines. Petitioners are bringing this suit as a

taxpaye'rs and citizens of the Philippines. Petitioners may be served

with pleadings, resolutions and other court processes in connection

with this case through their counsel, Roque & Butuyan Law Offices, at

1904 Ante! Corporate Center, 121 Valero Street, Salcedo Village, Makati

City.

As Filipino citizens, Petitioners have the right to sue to enforce

constitutional limits on the political branches of the government as well

as on the spending power of the government being as they are of

paramolmt public interest. This suit is being filed for the observance

and enforcement of the government's obligation to adhere to

constitlitional processes and principles pertaining to the doctrine of

3

separation of powers, the system of checks and balances and spending

powers enshrined in the 1987 Constitution.

As taxpayers, Petitioners have the right and expectation that

public money be used for public purposes, appropriated and disbursed

in accordance with well-defined constitutional and statutory allocation

of power under an effective system of checks and balances. As will been

shown hereunder, the DAP under N a tiona! Budget Circular No. 541

authorizes the spending of government money illegally and

unconstitutionally. Thus, Petitioners are not only bringing this suit

because public money is being illegally disbursed and will continue to

be illegally disbursed, Petitioners are equally suing to end the system of

budgetary appropriation and budgetary measures that allow such illegal

disbursement of public funds.

Respondent President Benigno Simeon C. Aquino, Ill is the

President of the Republic of the Philippines. He is named a respondent

in this case considering that the President, among other heads of

government agencies named therein, is specifically and personally

authorized to "augment any item in the general appropriations law for

their respective offices from savings in other items of their respective

appropriations."

4

The constitntional authority is specifically granted to

the President who alone can act on the matter and may not delegate the

same. Respondent President Aquino may thus be sued in his official

capacity pursuant thereto as an exception to the doctrine of sovereign

immunity from suit. Respondent may be served pleadings, resolutions,

decisions and other processes at Malacafiang Palace, J.P. Laurel Street,

San Miguel, Manila City.

Respondent Senate of the Philippines ("Senate"), represented by

Senate President Franklin M. Drilon, is the upper house of the Congress

of the Philippines granted by the Constitution with, among other

legislative powers, the power of appropriations.

5

It may be served with

pleadings, resolutions, decisions of other court processes at GSIS

Headquarters Building, Financial Center, Roxas Boulevard, Pasay City.

Respondent House of Representatives ("HoR"), represented by

Speaker Feliciano Belmonte, Jr.. is the lower house of the Congress of

the Philippines where appropriation bills, among others, originate

exclusively.

6

It may be served with pleadings, resolutions, decisions or

other court processes at House of Representatives Complex,

Constitution Hills, Quezon City.

4

Section 25 (5), Article VI, 1987 Constitution.

5

Section 24, Article VI, 1987 Constitution.

6

Ibid.

4

Respondent Executive Office ("EO") is an oftlce under the Office of

the President Proper headed at present by Executive Secretary Paquito

S. Ochoa. Among other functions, Respondent directly assists the

President "in the management of the affairs pertaining to the

Government of the Republic of the Philippines"

7

and decides on

"matters not requiring personal presidential attention."

8

Respondent

may be served with pleadings, resolutions, decisions of other court

processes at the Premiere House Guest, Malacaf\ang Palace, J.P. Laurel

Street, San Miguel, Manila City.

Respondent Department of Budget and Management ("DBM"),

represented by Secretary Florencio B. Abad, is one of the departments of

the Executive Branch of the Republic of the Philippines tasked with

assisting the "President in the preparation of the national resources and

expenditure budget"

9

and is responsible for the "formulation and

implementation" of the same and for the "efficient and sound utilization

of government funds and revenues."

10

Respondent may be served with

pleadings, resolutions, decisions and other court processes at its offlce

at General Solano Street, San Miguel, Manila.

Respondent Department of Finance ("DOF") represented by

Secretary Cesar V. Purisima, is one of the departments of the Executive

Branch of the Republic of the Philippines, tasked, among other, with the

custody and management of "all financial resources of the national

government" tl and as supervisor of the implementation of the

"government's resource mobilization efforts" "involving all purlbic

sector resources whether generated by revenues and operations,

foreign and domestic borrowing, sale or privatization of corporations or

assets, or from other sources."lZ Respondent may be served with

pleadings, resolutions and decisions ot other court processes at its office

at DOF Building, BSP Complex, Roxas Boulevard, 1004 Metro Manila.

Respondent Bureau of Treasury ("BTr,"), represented by National

Treasurer Rosalia V. De Leon, is an agency under the Department of

Finance tasked, among others, with the management of the cash

resources of the national government, acts as custodian of the "financial

assets of the of the national government, its agencies and

instrumentalities" and "take charge of the effective management of the

NG's cash receipts and disbursements."13 Respondent may be served

-------- ---

7

Section 27 (1], Chapter 9, Title Ill, Book III, Administrative Code of 1987.

0

Ibid., Section 27 (2).

9

Section 3, Chapter 1, Title XVII, Book IV, Administrative Code of 1987.

10

Ibid., Section 2_

JJ Sec. 3 (4), Chapter l, i'itle II, Boo!< IV, Administrative Code of 1987.

12

Sec. 3(1], Chapter 1, Title II, Book IV, Administrative Code of 1987.

13

See Executive Order No_ 449 entitled Realigning the Organization of the Bureau of

Treasury dated 17 October 1997.

5

with pleadings, resolutions, decisions or other court processes at its

office at Palacio del Gobernador Building, lntramuros, Manila.

STATEMENT OF MATERIAL FACTS

The Disbursement Acceleration Program (DAP) has been justified

as brought about by the need to set up "a mechanism for accelerating

government expenditures, which the Aquino administration started in

October 2011 when slow spending threatened to jeopardize the

country's growth prospects that year."14

In the official webpage of Respondent Department of Budget and

Management ("DBM"), its "Frequently Asked Questions About the

Disbursement Acceleration Program (DAP)"

15

contains the following

justification:

2. What was the context when DAP was introduced?

The DAP was conceptualized in September 2011 and

introduced in October 2011, in the context of the prevailing

underspending in government disbursements for the first

eight months of 2011 that dampened the country's

economic growth. Such government intervention was

needed as key programs and projects, most notably public

infrastructure, were moving slowly. The need to accelerate

public spending was also brought about by the global

economic situation as well as the financial toll of calamities

in that year. While the economy has generally improved in

2012 and 2013, the use of DAP was continued to sustain the

pace of public spending as well as economic expansion.

As per the Respondent DBM, the funds used for the DAP allegedly

came from savings of the government and allegedly in compliance with

the relevant laws

1

6 and the Constitution. Respondent DBM had the

following to say on the sourcing of funds, to wit:

1

4 See Clare Cattleya G. Amador, Assistant Secretary of the Department of Budget and

Management. in her Letter to the Editor of Philippine Daily Inquirer at

htm;JloJii n ion. inquirer. n eJ:LQ 3 409/ db IJ1:.Q!l- da ps-nature-s o_rr rei ng- dis burs_ em en ts :.etc .

15

See httujf.www,dbm.gov.ph /?page_

16

The provisions of the General Appropriations Act ofZOll to 2013 are as follows:

a. Genernl PrQvisions on the Use of Sayings. R.A. l01lJ.GAI!_l'Y.2.!!1l} _

Sec. 59. Use of Savings. The President of the Philippines, the Senate President, the Speaker

of the House of Representatives. the Chief justice of the Supreme Court, the Heads of

Constitutional Commissions enjoying fiscal autonomy, and the Ombudsman are hereby

authorized to augment any item in this Act from savings in other items of their respective

appro pria ti o ns.

Sec. 60. Meaning of Savings and Augmentation. Savings refer to portions or balances of

6

any programmed appropriation in this Act free from any obligation or encumbrance which

are: (i] still available after the completion or tlnal discontinuance or abandomnent of the

work, activity or purpose for which the appropriation is authorized; (ii) from

appropl"iations balances arising from unpaid compensation and related costs pertaining to

vacant positions and leaves of absence without pay; and (iii) from appropriations balances

realized from the implementation of measures resulting in improved systems and

efficiencies and thus enabled agencies to meet and deliver the required or planned targets,

programs and services approved in this Act at a lesser cost

Augmentation implies the existence in this Act of a program, activity, or project with an

appro_l]riation, which upon implementation, or subsequent evaluation of needed resources,

is determined to be deficient. In no case shall a program, activity, or project, be

funded by augmentation from savings or by the use of appropriations authorized

in this Act.

Sec. 61. Priority in the Use of In the use of savings, priority shall be given to the

augmentation of the amounts set aside for compensation, year-end bonus and cash gift,

retirement gratuity, terminal leave benefits, pension of veterans and other

personnel benefits authorized by law, and those expenditure items authorized in agency

special provisions, in Section 16 and in other sections of the General Provisions of this Act

b. ;eneri!LProvisions on the Use ofSavi11g!>,RA 10155(FY2012i!AAl

Sec. 53. Use of Savings. The President of the Philippines, the Senate President, the Speaker

of the House of Representatives, the Chief justice of the Supreme Court, the Heads of

Constitutional Commissions enjoying fiscal autonomy, and the Ombudsman are hereby

authorized to augment any item in this Act from savings in other items of their respective

Sec. 54-. Meaning of Savings and Aug1nentation. Savings refer to portions or balances of

any programmed appropriation in this Act free from any obligation or encumbrance which

are: [i] still available atter the completion or tlnal discontinuance or abandonment of the

work, activity or purpose for which the appropriation is authorized; (ii) from

appropriations balances arising from unpaid compensation and related costs pertaining to

vacant positions and leaves of absence without pay; and (iii) from appropriations balances

realized from tlle implementation of measures resulting in improved systems and

efficiencies and thus enabled agencies to meet and deliver the required or planned targets,

programs and services approved in this Act at a lesser cost.

Augmentation implies the existence in this Act of a program, activity, or proJect with an

appropriation, which upon implementation or subsequent evaluation of needed resources,

is determined to be deficient. In no case shall a non-existent program, activity, or project, be

flmded by augmentation from savings or by the use of appropriations otherwise authorized

in this Act.

Sec. 55. Priority in the Use of Savings. In the use of savings, priority shall be given to the

augmentation of the amounts set aside for compensation, bonus and cash gift,

retirement gratuity, terminal leave benefits, oldage pension of veterans and other

personnel benefits authorized by law, and those expenditure items authorized in agency

special provisions and in other sections of the General Provisions of this Act.

c. Ge!eral Provision!;i_On the Use of Savings, RA 10352 (FY2013 GilJ)J

Sec. 52. Use of Savings. The President of the Philippines, the Senate President, the Speaker

of the House of Representatives, the Chief justice of the Supreme Court, the Heads of

Constitutional Commissions enjoying fiscal autonomy and the Ombudsman are hereby

authorized to use savings in the their respective appropriations to augment actual

deficiencies incurred the current year in any item of their respective appropriations.

Sec. 53. Meaning of Savings and Augmentation. Savings refer to portions or balances of

any appropriation in this Act free from any obligation or encumbrance which

are: (i] still availahle after the completion or final discontinuance or abandonment of the

work, activity or pmpose for which the appropriation is authorized; (ii) from

appropriations balances arising from unpaid compensation and related costs pertaining to

vacant positions afld leaves of absence without pay; <Hid (iii) from appropriations babnces

realized from the implementation of measures resulting in improved systems and

efficienCies and thus enabled agencies to meet and deliver the required or planned targets,

7

C. Sourcing of Funds for DAP

l. How were funds sourced?

Funds used for programs and projects identified through

DAP were sourced from savings generated by the

government, the realignment of which is subject to the

approval of the President; as well as the Unprogrammed

Fund that can be tapped when government has windfall

revenue collections, e.g., unexpected remittance of

dividends from the GOCCs and Government Financial

Institutions (GF!s ), sale of government assets.

2. Where did savings come from?

Savings were sourced from:

a) the pooling of unreleased appropriations such as

unreleased Personnel Services appropriations which will

lapse at the end of the year, unreleased appropriations of

slow moving projects and discontinued projects per

Zero-Based Budgeting findings; and

b) the withdrawal of unobligated allotments, also for

slow-moving programs and projects, which have earlier

been released to national government agencies.

In line with laws on the use of savings (see below), DBM

ensured that programs and projects funded through DAP

have an appropriation cover; meaning, these are existing

programs and projects in the General Appropriations Act

(GAA) that can be augmented by such savings.

The total expenditure of public funds under the DAP since its

inception and to what these funds were supposedly used have been

summarized by Respondent DBM in its Frequently Asked Questions as

follows:

programs and services ctpproved in this Act at a lesser cost.

Augmentation implies the existence in this Act of a program, activity, or project with all

appropriation, which upon implementation or subsequent evaluation of needed resources,

is determined lobe deficient. In no case shall a non-existent program, activity, or project, be

funded by augmentation from savings or by the use of appropriations otherwise authorized

ill this Act.

Sec. 56. Priority in the Use of Savings. In the use of savings, priority shall be given to the

augmentation of the amounts set aside for compensation, year-end bonus and cash gift,

retirement gratuity, terminal leave benefits. old-age pension of veterans and other

personnel benefits authorized by law, and those expenditure items aullHJrized in agency

special provisions and in other sections of the General Provisions of this Act.

8

B. Amounts and Purposes Funded through DAP

1. How much were the programs and projects funded

through DAP in 2011, 2012, and 2013?

For 2011-2012, a total of P142.23 Billion was released for

programs and projects identified through the DAP, of which

P83.53 Billion is for 2011 and 58.70 Billion is for 2012.

In 2011, the amount was used to provide additional funds

for programs/projects such as healthcare, public works,

housing and resettlement, and agriculture, among others.

While in 2012, these were used to augment tourism road

infrastructure, school infrastructure, rehabilitation and

extension of light rail transit systems, and sitio

electrification, among others.

In 2013, about P15.13 Billion has been approved for the

hiring of policemen. additional funds for the

modernization of PNP, the redevelopment of Roxas

Boulevard, and funding for the Typhoon Pablo

rehabilitation projects for Compostela Valley and Davao

Oriental. (Emphasis supplied)

2. What kind of projects are funded through the DAP?

The programs and projects submitted to the DBM must

meet the following conditions:

a) Fast-moving or quick-disbursing, e.g. the payment of

obligations incurred from premium subsidy for indigent

families in the National Health Insurance Program;

b)Urgent or priority in terms of social and economic

development objectives, e.g. the upgrading of equipment

and facilities for specialty hospitals, rehabilitation of Light

Rail Transit and Metro Rail Transit, and the Disaster Risk

and Exposure I?JAssessmeut and Mitigation (DREAM)

program of DOST;

c) Programs or projects performing well and could deliver

more services to the l?lpublic with the additional funds e.g.

Training for Work Scholarship Program of DOLE-TESDA.

Some of the items funded through the DAP are expenditures

which are mandated by law, such as capital infusion for the

Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (R.A. 7653, Section 2) out of the

augmented Budgetary Support to Government

Co rpo rations-Others.

Out of the P142.23 Billion expended for 2011 and 2012, the

amount coursed through legislators amount to the equivalent of nine

9

percent (9%) of the said total amount or approximately P13 Billion as

disclosed in the FAQs, to wit:

3. How much were the programs and projects that were

endorsed by legislators?

The legislators have also endorsed programs and projects

for the social and economic benefit of their constituents,

such as medical assistance and local infrastructure projects.

The proposals were funded through DAP as they are

existing budgetary items in the GAA and compliant with the

conditions stated above.

Of the total DAP approved by OP for 2011-2012 amounting

to a total of P142.23 Billion only 9 percent was released to

programs and projects identified by legislators. These were

not released directly to legislators but to implementing

agencies.

Contrary to the foregoing representations of the Respondents, the

underlying policy for the DAP is governed by a belatedly issued circular

of Respondent DBM dated 18 July 2012 or almost ten (10) months after

the program was started. On said date Respondent DBM issued National

Budget Circular No. 5411

7

(NBC 541).

The provisions of National Budget Circular No. 541 shall be

discussed hereunder in relation to the issues raised in this Petition.

While the circular purportedly covers only the 2011 and 2012 budget,

the pronouncements of the spokespersons of Respondent President on

non-abolition of the DAP, the President's reported refusal to scrap and

on the contrary, even vowed to continue the DAP, plus the absence of

another circular involving the GAA of 2013 can only lead to Circular No.

541 being the basis for the continued enforcement and implementation

of the DAP.

Moreover, the provisiOns of the GAA for 2013 on the use of

savings used by Respondent President in the previous years under the

DAP does not justify the enormous amount under the program unless

projects were purposely proposed in the budget with the intention of

having the same discontinued or abandoned. But then again, these

savings may only be used to augment actual programs or projects with

actual deficiencies. From the pronouncements of the spokespersons of

the President and by some portion of the DAP having been coursed

through many legislators, there is a reasonable probability that these

17

See

;;o lltso n t/ '' n! o Is :;u ances I 2Dl21L!et i o IE!l'lil2 0 f;i u dge t%2 o Glr cuI a r 1 fi!K 5 HlN BC 2QJ2,

!:iLpdi.

10

funds were used for new projects and not merely to augment actual

deficiencies.

18

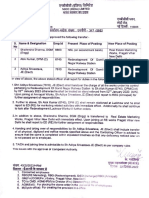

The coursing of of the DAP funds through legislators and the use

to which such funds were devoted to are exemplified by a recent report

that in 2011, at least six Senators identified projects worth PlOO Million

pesos for each of them under the DAP.19 A sample letter accompanying

the news report reads:

,(,., . '

.. ,._.,.

fRAl<HLOI Jot D!UtQJO

'"'"'"'"''

.__.,,.,- "''''' "'' l m

,; ::.:,,1'1;1

\",,,,,, '"'

.. .. ;:;.:,; I I

li! f<l/ """) i '"'l'" h>{i, . <I'" .ii<:,;l:o,J h'< ,f f."""''-.,

,,,-, ':.' "' OlOB Bl.ll'fDRtm PtUO:f If' 100.0\XUXl<l.OOj !> ,j,," -,

>v. ......

f, . . ,, <.') .\-'""""' h>

bt ill : I

; 1",="1 "'' ,. !"

'<.I.W p,, ,.,

i f:>lTC"

Hence, this Petition.

WOUKl' I

1

_

l/l"<>lSt' h-<1

i l'kxn hM

l

18

See htt!lJ/new;;i.nfQjJllj!lirer.net/ 49Jl215 /unused- funds- from-_governm en t-aggncjg;;,

went-to-abads::]l[Qgrarn . See also http: ((www.gov.ph/2Jl13 /09 /3i)j:;tatemgn.t::the-

secretarv-of-budget -on-the- releases-to-senators/ . Also,

http.J/_l'lwWgov,phl:>ection/brlefing-roomjde)2;lrtment-of-budget:and:nla!1agementJ.

19

See http;i/newsinfo.illquirer.net /505 61M OOm-each- for-6senators-fro]n-dau .

11

GROUNDS

A. THE DISBURSEMENT ACCELERATION PROGRAM AND THE FUND

RELEASES PURSUANT THERETO ARE UNCONSTITUTIONAL INSOFAR

AS IT INVOLVE FUNDS RELEASED PURSUANT TO FUNDING REQUESTS

BY LEGISLATORS FOR BEING IN VIOLATION OF THE SEPARATION OF

POWERS AND THE DOCTRINE OF CHECKS AND BALANCES.

B. THE DISBURSEMENT ACCELERATION PROGRAM OF THE

PRESIDENT COMING FROM PURPORTED SAVINGS ARE

UNCONSTITUTIONAL AND ILLEGAL INSOFAR AS IT INCLUDED FUNDS

NOT FALLING UNDER THE DEFINITION OF SAVINGS IN THE

CONSTITUTIONAL SENSE AND UNDER APPLICABLE THE GENERAL

APPROPRIATIONS ACTS.

C. THE PROVISIONS PERTAINING TO AND THE USE AND RELEASES

UNDER THE DISBURSEMENT ACCELERATION PROGRAM

UNCONSTITUTIONAL AND ILLEGAL INSOFAR AS THESE PERTAINED

TO OR WERE USED TO FUND NEW PROJECTS AND PROGRAMS AND

NOT MERELY FOR THE PURPOSE OF AUGMENTING EXISTING

PROGRAMS AND PROJECTS WITH BUDGETARY DEFICITS.

D. THE PROVISIONS PERTAINING TO AND THE USE AND RELEASES

UNDER THE DISBURSEMENT ACCELERATION PROGRAM OF THE

PRESIDENT ARE ILLEGAL INSOFAR AS THESE PERTAINED TO AND

FUNDED PROGRAMS AND PROJECTS IN VIOLATION OF THE

PRIORITIES LISTED UNDER SECTION 56 OF THE GENERAL

APPROPRIATIONS ACT OF 2013.

E. THE USE OFTHE DAP FUNDS TO AUGMENT THE PROVISIONS OF

THE GENERAL APPROPRIATIONS ACT OF 2013 WHICH ARE IN THE

NATURE OF LUMP SUM DISCRETIONARY APPROPRIATIONS SUCH AS

UNDER TITLE XXXV!Il OF R.A. NO. 10352 ON THE CONTINGENCY

FUND, UNDER TITLE XXXVII ON THE CALAMITY FUND, UNDER TITLE

XLV ON THE UNPROGRAMMED FUND, UNDER TITLE XXXV ON

BUDGETARY SUPPORT FOR GOCCS, THE PRIORITY DEVELOPMENT

ASSISTANCE FUND AND SUCH OTHER SPECIAL PURPOSE FUNDS IS

UNCONSTITUTIONAL FOR BEING CONTRARY TO SECTION 25 (1)

ARTICLE VI OF THE CONSTITUTION IN RELATION TO THE PROVISIONS

OF P.D. NO. 1177 AND THE ADMINISTRATIVE CODE OF 19B7.

12

DISCUSSION

A. THE DISBURSEMENT ACCELERATION PROGRAM AND THE FUND

RELEASES PURSUANT THERETO ARE UNCONSTITUTIONAL INSOFAR

AS IT INVOLVE FUNDS RELEASED PURSUANT TO FUNDING REQUESTS

BY LEGISLATORS FOR BEING IN VIOLATION OF THE SEPARATION OF

POWERS AND THE DOCTRINE OF CHECKS AND BALANCES.

While the GAA of 2011, 2012 and 2013 all have provisions on the

Priority Development Assistance Fund (PDAF) and the manner of its

utilization, the DAP implemented in 2011, 2012 ancl2013 only has NBC

541 as its guideline albeit the Respondents claim that this was issued in

accordance with the laws and the Constitution.

However, with respect specifically to the use of the DAP funds

coursed through funding requests by legislators, there appears to be no

statutory nor administrative basis therefor.

If the PDAF governed by the provisions of the general

appropriations act is already constitutionally objectionable, there is

reason to believe that the use of DAP funds in a manner akin to the use

of PDAF is equally, if not more so, unconstitutional.

The GAA of 2011, 2012 and 2013 are legislative enactments upon

the passage of which there is nothing for the government to do but for

the executive to implement or execute the policy embodied in the laws.

The participation of the legislators was complete upon the passage of

the law. Everything that needs to be done thereafter, except in cases

where Congress exercises its power to override a presidential veto,zo

pertains to the executive department of the government.

In the case of DAP, as in PDAF, it authorized legislators to

participate in the implementation and execution of the law by way of

identification of the programs or projects. On this score, the difference

between DAP and PDAF is that while the PDAF has the provisions of the

GAA to rely on, there is no law or administrative regulation that allows

congressional participation in the expenditure of funds pursuant to the

budget- not even NBC 541.

While such congressional participation in the identification of

programs or projects may be termed as "recommendatory" as in the

case of PDAF as claimed by the executive department, it still does not

detract from the fact that the function being done by a member of

Congress is one pertaining to the executive department especially since

20

Sections 26 & 27, Article VI, 1987 Constitution.

13

the funds earmarked for use under DAP do not pertain to specific

appropriations but constitutes a general fund.

The practice under PDAF, and in this case, the DAP, is an undue

and unjustified legislative encroachment in the realm of the executive

contrary to Section 1 of Article VII of the 1987 Constitution. Said

provision proclaims the basic principle of our government that

"executive power shall be vested in the President of the Philippines."

Alone.

While the President may exercise his executive power through his

subordinates who are subject to his control and supervision, he may not

share his executive power with a member of a coordinate but separate

department of the government who is not subject to his control and

supervision.

Neither can Members of Congress or the judiciary for that matter,

exercise functions that intrude into the executive domain.

This is the essence of the doctrine of separation of powers. Except

in cases of valid delegation of legislative powers, the doctrine of

separation of powers entails a prohibition on one department in sharing

its powers with the other departments and a proscription against

encroachment by one department into the exclusive domains of the

other departments of government.

Respondent President's act of sharing his executive power with

members of the Legislature if only in the identification of projects or

recommendation of programs or projects after, outside of and beyond

the legislative deliberations on the budget and during the execution and

implementation of the general appropriations laws violates the doctrine

of separated powers in the three branches of the government.

In this connection, the discussion in the case of Abakada Gum

Party List vs. Purisima

21

is instructive, to wit:

Where Congress delegates the formulation of rules to

implement the law it has enacted pursuant to sufficient

standards established in the said law, the law must be

complete in all its essential terms and conditions when it

leaves the hands of the legislature. And it may be deemed to

have left the hands of the legislature when it becomes

effective because it is only upon effectivity of the statute

that legal rights and obligations become available to those

entitled by the language of the statute. Subject to the

21 G.R. No. 166715; 14 August 2008.

14

indispensable requisite of publication under the due

process clause, the determination as to when a law takes

effect is wholly the prerogative of Congress. As such, it is

only upon its effectivity that a law may be executed and

the executive branch acquires the duties and powers to

execute the said law. Before that point. the role of the

executive branch, pa1ticularly of the President, is

limited to approvinl! or vetoing the law.

From the moment the law becomes effective. any

provision of law that empowers Congress or any of its

members to play any role in the implementation or

enforcement of the law violates the principle of

separation of powers and is thus unconstitutional.

Under this principle, a provision that requires Congress or

its members to approve the implementing rules of a law

after it has already taken effect shall be unconstitutional, as

is a provision that allows Congress or its members to

overturn any directive or ruling made by the members of

the executive branch charged with the implementation of

the law. (Emphasis supplied)

In the case of DAP, while there is no statutory pmvision on post

enactment legislative participation, the fact that the general

appropriations laws have long left the hands of Congress and were in

fact already being implemented by the executive, any congressional

participation at that stage is already an encroachment in the executive

domain. It is, pursuant to the above-quoted case of Abakacla,

unconstitutional.

Now, in allowing or authorizing the legislators to participate in

the implementation of the general appropriations laws by identifying

the projects and programs that may be funded by the DAP, does such

consent on the part of the President change the character of the act of

the legislators and make the same legal and constitutional?

Most definitely not. As in the case of Abakada, even if the law itself

authorizes the legislators' post enactment participation in the

implementation of the law and such authorization is still

unconstitutional, then with all the more reason it is unconstitutional

when the law does not contain such authorization even if the legislators'

participation is made possible by the initiative or consent of the

President. '

Moreover, the foregoing arrangement creates excessive

entanglement between the executive and the legislature on a matter

that is essentially executive in character. This entanglement has

15

resulted in the blurring of or confusion in the functions of the

implementing agencies and the legislators and with respect to the

allocation of responsibility and legal accountability as exemplified by

the experience involving the PDAF.

In the COA Special Audit Report

22

on the congressional pork

barrel, following are some of the material findings

23

that were contrary

to the special provisions or guidelines on the use of PDAF under the

general appropriations laws, to wit:

On livelihood and other projects:

1. The release of P6.156 Billion to NGOs despite the absence

of an appropriation law or ordinance;

2. The selection of the NGOs "on the basis alone of the

purported endorsement by the sponsoring legislators and not

through public bidding."

3. The implementation of 772 projects by the selected 82

NGOs out of funds transferred by 10 lAs amounting to P6.156

Billion (See Table 15} was not proper and highly irregular

24

as the

NGOs and their suppliers: could not be located or are unknown;

found to have not business permits and registration papers; were

charging their operating expenses such as salaries and

administrative expenses against the PDAF; some of the NGOs are

managed/incorporated by the same persons; submitted list of

beneficiaries whose names were taken from board or bar

examination passers; or incorporated by the legislators

themselves, among others.

For Infrastructure projects:

4. Forty-one projects costing P1.393 Billion were found

deficient by P46.262 Million and were not constructed strictly in

accordance with plans and specifications or included excessive

quantities of reflective pavement studs (RPS) and other

construction materials.

5. Projects constructed in private lots costing P161.498

Million.

zz The Honorable Court is invited to take judicial notice of the COA Special Audit Report No.

2012-03 on Priority Development Assistance Fund and Various Infrastructure including

Local Projects. A copy of the Report may be downloaded from the COA website at

www.coa,gQ.'LJlh .

2

' See pp. 15-19 of the Report.

24

Ibid.

16

6. Excessive contracts amounting to P100.989 Million due to

erroneous application of rates and splitting of contracts.

Aside from the foregoing, more revealing for the purpose of this

Petition are the following claims of implementing agencies

25

, among

others, to wit:

l. Intervention in the implementation of livelihood projects

tended to be more recommendatory in nature or was merely to

facilitate the transfer of funds, as the projects and NGOs were

endorsed by the sponsoring legislators.

2. The National Livelihood Development Corporation

("NLDC") has fully relied on the Office of the Legislators to

supervise and ascertain project implementation.

3. The project implementation is directly participated by the

proponent legislators.

4. Fund transfers or financial assistance were granted upon

the request or direction of the sponsoring legislators. The LGUs

merely acted as initial depository and conduit of the funds.

If despite the guidelines in the general appropriations Jaws on the

use of congressional pork barrel, the implementing agencies, the

Respondent DBM and the legislators were still able, whether by design

or negligence, to perpetrate the foregoing deeds, then there is reason to

be afraid that more than the foregoing can be clone with respect to DAP

funds where there are no guidelines in the participation of the

legislators in the implementation of the program.

On the other hand, aside from the legislative encroachment in the

domain of the executive, the DAP implemented by Respondent

President arrogated unto himself the powers of the Congress to

appropriate public funds. This is evident from the President's directive

under NBC 541 to use the DAP funds "to fund priority pmg1ams and

projects not considered in the 2012 budget but expected to be

started or implemented during the current year." Such directive is

clearly a usurpation of the power of the legislature to appropriate

government funds. Such power did not originate from the House or

Representatives nor did it pass the legislative process under the

Constitution.

2

5 See pp. 19-22 of the Report

17

Equally important, such use of the DAP funds is violative of

Section 29 (1 ), Article Vl of the Constitution which requires that "No

money shall be paid out of the Treasury except in pursuance of an

appropriation made by law." In this case, NBC 541 even contemplates -

even as it acknowledges- the use of DAP funds for programs or projects

not in the current budget but only contemplated by the executive to be

implemented or started within 2012 notwithstanding the absence of an

appropriation therefor.

It is simply a blatant violation of the aforesaid Constitutional

prohibition.

B. THE DISBURSEMENT ACCELERATION PROGRAM OF THE

PRESIDENT COMING FROM PURPORTED SAVINGS ARE

UNCONSTITUTIONAL AND ILLEGAL INSOFAR AS IT INCLUDED FUNDS

NOT FALLING UNDER THE DEFINITION OF SAVINGS IN THE

CONSTITUTIONAL SENSE AND UNDER THE APPLICABLE GENERAL

APPROPRIATIONS ACTS.

The applicable provision of the Constitution on this subject reads:

Sec. 25 (5) No law shall be passed authorizing any

transfer of appropriations; however, the President, the

President of the Senate, The Speaker of the House of

Representatives, the Chief justice of the Supreme Court, and

the heads of Constitutional Commissions may, by law, be

authorized to augment any item in the General

Appropriations law for their respective offices from savings

in other items of their respective appropriations26

The foregoing constitutional provision has been given legislative

interpretation in the GAA of 2013 as follows:

Sec. 52. Use of Savings. The President of the

Philippines, the Senate President, the Speaker of the House

of Representatives, the Chief justice of the Supreme Court,

the Heads of Constitutional Commissions enjoying fiscal

autonomy, and the Ombudsman are hereby authorized to

use savings in their respective appropriations to augment

actual deficiencies incurred for the current year in any item

of their respective appropriations.

Sec. 53. Meaning of Savings and Augmentation.

Savings refer to portions or balances of any programmed

'

6

Article VI, 1987 Constitution.

18

appropriation in this Act free from any obligation or

encumbrance which are: (i) still available after the

completion or final discontinuance or abandonment of the

work, activity or purpose for which the .appropriation is

authorized; (ii) from appropriation balances arising tiom

unpaid compensation and related costs pertaining to vacant

positions and leaves of absences without pay; and (iii) from

appropriation balances realized from the implementation of

measures resulting in improved systems and efficiencies

and thus enabled agencies to meet and deliver the required

or planned targets, programs and services approved in this

Actatalessercost

Augmentation implies the existence in this Act of a

program, activity, or project with an appropriation, which

upon implementation or subsequent evaluation of needed

resources, is determined to be deficient. In no case shall a

non-existent program, activity, or project be funded by

augmentation from savings or by the use of appropriation

otherwise authorized in this Act.

From the foregoing definition of savings, there is nothing

mysterious or complicated with regard to the term as it is known to

ordinary men and women. The term savings refers to the excess money

after all that needs to be funded have been funded or those that needed

to be paid have been paid pursuant to the budget.

It appears, however, that what the government has done, to a large

extent, was to make forced savings to the point of not funding certain

appropriation items under the budget so as to be able to come up with a

larger "savings" for discretionary spending.

This is borne by Respondent's National Budget Circular No. 54127

which provides as its Rationale, the "withdrawal of

allotments of agencies with low levels of obligations as of june 30,

2012, both for continuing and current allotments. This measure will

allow the maximum utilization of available .allotments to fund and

undertake other priority expenditures of the national government."

While the rationale seems vague in its reference to "unobligated

allotments", the purpose of the circular gives a clue as to the real

nature of the move, to wit:

2.0 Purpose

27

See hUll: //www c!brngQY,Jllib.\'!l:

co LZ-.012/N a tiQ!li!l%2 0 OCirculi!rL.!"Jll.C54ljN B.CZill:

.SiLu.Qf.

19

2.1 To provide the conditions and parameters on the

withdrawal of unobligated allotments of agencies as of June

30, 2012 to fund priority andjor fast-moving

programs/projects of the national government;

2.2 To prescribe the reports and documents to be used as

bases on the withdrawal of said unobligated allotments; and

2.3 To provide guidelines in the utilization..m:_reallocation

of the withdrawn allotments. (Emphasis supplied)

The coverage of the circular is especially significant. The circular

states that:

3.1 These guidelines shall cover the withdrawal of

unobligated allotments as of hme 30. 2012 of all

national government agencies (NGAs) charged against

FY 2011 Continuing Appropriation (R.A. No. 10147) and

FY 2012 Current Appropriation (R.A. No. 10155.}

pertaining to:

3.1.1 Capital Outlays (CO);

3.1.2 Maintenance and Other Operating Expenses (MOOE)

related to the implementation of programs and projects, as

well as capitalized MOOE; and

3.1.3 Personal Services corresponding to unutilized pension

benefits declared

as savings by the agencies concerned based on their

updated/validated list of pensioners.

3.2 The withdrawal of unobligated allotments may cover the

identified programs, projects and activities of the

departments/agencies reflected in the DBM list shown as

Annex A or specific programs and projects as may be

identified by the agencies.

Considering that the DAP was implemented as early as October

2011 or three months before the end of the year, it is inconceivahle how

savings could have been generated in the constitutional and statutory

sense since the fiscal year has not yet expired unless these savings were

taken from abandoned projects or programs.

Even so, granting for the sake of argument that the withdrawal of

unobligated allotments for FY 2011 may arguably cover only savings in

the constitutional and statutory sense, the same thing cannot be said of

the withdrawal of unobligated allotments for FY 2012 considering that

it was, at the time of the issuance of the circular in July 2012, just the

20

middle of the year and there is yet much time to spend the allotments in

accordance with the appropriations law.

That the circular covered even those funds which are not legally

considered savings is clear from Guidelines proper of the circular itself.

Section 5.1. thereof provides:

5.1 National government agencies shall continue to

undertake procurement activities notwithstanding the

implementation of the policy of withdrawal of unobligated

allotments until the end of the third quarter, FY 2012. Even

without the allotments, the agency shall proceed in

undertaking the procurement processes (i.e., procurement

planning up to the conduct of bidding but short of awarding

of contract) pursuant to GPPB Circular Nos. 02-2008 and

01-2009 and DBM Circular Letter No. 2010-9.

Thus, even existing programs and projects which are due for

bidding were subjected to the withdrawal of their "unobligated

allotments" and were therefore deprived of funding. That this is so is

evident from the directive to continue with the bidding process but not

to proceed with the award to the winning bidder.

This is further supported by Section 5.4 of the circular which reads:

5.4 All released allotments in FY 2011 charged against ItA.

No. 10147 which remained unobligated as of June 30, 2012

shall be immediately considered for withdrawal. x x x

The release of allotments on the basis of the budget for 2011 means

that the programs or projects have not yet been finally discontinued or

abandoned and may in fact be still undergoing implementation. The

fund then still unused, that is, unobligated, are not yet legally and in the

constitutional sense, savings. To withdraw the funds therefor on the

ground that it is still unobligated is not to use savings but to use

allocations for existing budgetary appropriations.

The very concept of an "unobligated allotment" itself presupposes

the existence of a program or project funded by an appropriation law

whereby the agency charged with the implementation of the program or

project has not yet incurred an obligation with respect thereto. That is

why it is called "unobligated allotment."

This may be gleaned from the definition of "allotment" under

Section 2 (2), Chapter 1, Book VI of the Administrative Code of 1987.

The provision states:

21

(2) "Allotment" refers to an authorization issued by

the Department of Budget to an agency, which allows it to

incur obligation for specified amounts contained in a

legislative appropriation.

Thus, in one fell swoop and by the mere expedient of using the term

"unobligated allotments," Respondents from the executive department

redefined the term "savings" via a mere circular, the constitutional and

legal definition thereof notwithstanding.

Furthermore, such practice of withdrawing "unobligated

allotments" sanctioned by the circular is clearly against the law. The

GAA of 2013 prohibits the retention or deduction of allotments as

follows:

Sec. 66. Prohibition Against Retention or Deduction of

Allotment. Fund releases from appropriations provided in

this Act shall be transmitted intact or in full to the agency

concerned. No retention or deduction as reserves or

overhead shall be made, except as authorized by law, or

upon direction of the President of the Philippines.

The provision under the GAA of2012 is, in a sense, more strict than

the GAA of 20Ll in that it mandated COA to ensure that this prohibition

is obser'ved by the government, to wit:

Sec. 66. Prohibition Against Retention or Deduction of

Allotment. Fund releases from appropriations provided in

this Act shall be transmitted intact or in full to the agency

concerned. No retention or deduction as reserves or

overhead shall be made, except as authorized by law, or

upon direction of the President of the Philippines. The COA

shall ensure compliance with this provision to the extent

that sub-allotments by agencies to their subordinate offices

are in conformity with the release documents issued by the

DBM.

The same provision exists in the GAA of 2 011, to wit:

Sec. 68. Prohibition Against Retention/Deduction of

Allotment. Fund releases from appropriations provided in

this Act shall be transmitted intact or in full to the office or

agency concerned. No retention or deduction as reserves

or overhead shall be made, except as authorized by law, or

upon direction of the President of the Philippines. The COA

shall ensure compliance with this provision to the extent

that sub-allotments by agencies to their subordinate offices

22

are in conformity with the release documents issued by the

DBM.

If the respondents from the executive department cannot even

reduce or deduct from the allotment while the money is still with them,

then, it stands to reason that the prohibition includes the withdrawal of

the allotments so long as it does not acquire the character of savings.

Respondents cannot reduce or retain funds for allotments by the mere

expedient of withdrawing such allotments on the ground that it is

unobligated. The legal maxim that what cannot be done directly cannot

be done indirectly is applicable in this case.

There can thus be no doubt that this practice of the respondents

from the Executive Department is unconstitutional and illegal.

C. THE PROVISIONS PERTAINING TO AND THE USE AND RELEASES

UNDER THE DISBURSEMENT ACCELERATION PROGRAM ARE

UNCONSTITUTIONAL AND ILLEGAL INSOFAR AS THESE PERTAINED

TO OR WERE USED TO FUND NEW PROJECTS AND PROGRAMS AND

NOT MERELY FOR THE PURPOSE OF AUGMENTING EXISTING

PROGRAMS AND PROJECTS WITH BUDGETARY DEFICITS.

What is even more legally repugnant is the use of these unobligated

allotments. While the Constitution requires that the savings may only be

used to "augment any item in the general appropriations law" and the

GAA allows savings to be used to augment programs and projects with

budgetary deficits, the circular - the basis for the Disbursement

Acceleration Program - allows its use even to programs or projects not

existing in the General Appropriations law.

This is gleaned from the provision on the use of the withdrawn

allotments as follows:

5.7 The withdrawn allotment may be:

5.7.1 Reissued for the original programs and projects of the

agencies/OUs concerned, from which the allotments were

withdrawn;

5.7.2 Realigned to cover additional funding for other

existing programs and projects of the agency jOU; or

5.7.3 Used to augment existing programs and projects of

any agency and to fund priority programs and projects

not considered in the 2012 budget but expected to be

started or implemented during the current year.

(Emphasis supplied)

23

It is clear that insofar as "priority programs and projects not

considered in the 2012 budget but expected to be started or

implemented during the current year" are concerned, the expenditure of

funds under the DAP for these projects directly violate the

constitutional injunction that "No money shall be paid out of the

Treasury except in pursuance of an appropriation made by law."2B

The fact that these programs or projects are not part of the current

budget make them ineligible for funding with the use of savings as may

only be used "to augment any item in the general appropriations law for

their respective offices."29

Even its use for existing programs and projects part of the general

appropriations act is questionable insofar there is no budgetary deficit

or deficiency for such program or project.

Thus, an additional funding not just to cover a deficit in the

appropriation for an existing project is still unlawful.

D. THE PROVISIONS PERTAINING TO AND THE USE AND RELEASES

UNDER THE DISBURSEMENT ACCELERATION PROGRAM OF THE

PRESIDENT ARE ILLEGAL INSOFAR AS THESE PERTAINED TO AND

FUNDED PROGRAMS AND PROJECTS IN VIOLATION OF THE

PRIORITIES LISTED UNDER THE GENERAL APPROPRIATIONS LAWS.

No matter how noble the intention of the DAP program is,

Respondents cannot just ignore the law and the constitution.

Respondent cannot and should not be allowed to render inutile the

provision in the GAA of 2013 on the priority in the use of savings. 30

Section 56 reads:

28

Section 29 (1), Article VI, 1987 Constitution.

29

Section 25 (5), Article VI, Constitution.

30 GAA of 2011 states:

Sec. 61. Priority in the Use of Savings. In the use of savings, priority shall be given

to the augmentation of the amounts set aside for compensation, year-end bonus

and cash gift, retirement gratuity, terminal leave benetlts, old-age pension of

veterans and other personnel benefits authorized by law, and those expenditure

items authorized in agency special provisions, in Section 16 and in other sections

of the General Provisions of this Act.

The GAA of ZCII Z states:

Sec. 55. Priority in the Use of Savings. In the use of savings, priority shall be

given to the augmentation of the amounts set aside for compensation, year-end

bonus and cash gift, retirement gratuity, terminal leave benefits, old-age pension

of veterans and other personnel benefits authorized by Jaw, and those expenditure

items authorized in agency special provisions and in other sections of the General

Provisions of this Act.

24

Sec. 56. Priority in the Use of Savings. In the use of

savings, priority shall be given to the augmentation of the

amounts set aside for compensation, year-end bonus and

cash gift, retirement gratuity, terminal leave benefits, old-

age pension of veterans and other personnel benefits

authorized by law, and those expenditure items authorized

in agency special provisions and in other sections of the

General provisions in this Act.

The use of the "unobligated allotments" under the DAP not in

accordance with the foregoing legislative priority, especially the use for

programs and projects not included in the applicable general

appropriations laws is simply, illegal.

The foregoing reasons make the DAP under the present

administration worse than its Marcosian predecessor under Section 44

of Presidential Decree No. 1177 subject matter of the case of Demetria

vs. Alba3

1

. In the said case, the Supreme Court found as repugnant to the

1987 Constitution the blanket authority given to the president under

the law to transfer any funds in the executive department, whether it is

savings or not, to fund other programs or projects included in the

general appropriations act. The Supreme Court ruling states:

The conflict between paragraph 1 of Section 44 of

Presidential Decree No. 1177 and Section 16[5], Article VIII

of the 1973 Constitution is readily perceivable from a mere

cursory reading thereof. Said paragraph 1 of Section 44

provides:

The President shall have the authority to transfer any

fund, appropriated for the different departments,

bureaus, offices and agencies of the Executive

Department, which are included in the General

Appropriations Act, to any program, project or

activity of any department, bureau, or office included

in the General Appropriations Act or approved after

its enactment.

On the other hand, the constitutional provision under

consideration reads as follows:

Sec. 16[5]. No law shall be passed authorizing any

transfer of appropriations, however, the President,

the Prime Minister, the Speaker, the Chief justice of

the Supreme Court, and the heads of constitutional

3I G.R. No. 719"17; 27 February 1987.

25

commissions may by law be authorized to augment

any item in the general appropriations law for their

respective offices from savings in other items of their

respective appropriations.

The prohibition to transfer an appropriation for one

item to another was explicit and categorical under the 1973

Constitution. However, to afford the heads of the different

branches of the government and those of the constitutional

commissions considerable flexibility in the use of public

funds and resources, the constitution allowed the

enactment of a law authorizing the transfer of funds for the

purpose of augmenting an item from savings in another

item in the appropriation of the government branch or

constitutional body concerned. The leeway granted was

thus limited. The purpose and conditions for which

funds may be transferred were specified, i.e. transfer

may be allowed for the purpose of augmenting an item

and such transfer may be made only if there are

from another item in the appropriation of the

.!illvernment branch or constitutional body.

Paragraph 1 of of P.O. No. 1177 unduly

Qver extends said Section.16L51

It empowers __ the President to indiscriminately transfer

fut1ds fromOl1f department, bureau. office or agency of thf

Executive Department to any progran1, project or activity of

any depactment, bureau or _office included in__the General

Appropriations Act or approved after its enactmentwithQl!t

as to _whether or not the funds to be t1:ansferred are

actual!y_savings in the item. from which the same are to be

taken or whether or not the transfer is for the purpose of

augmentingthe item to which said_transfer is to be made. It

daes not only completely disregard the standards set in

the fundamental law, thereby amounting to an undue

delegation of legislative powers, but likewise goes

beyond the tenor thereof. Indeed, such constitutional

infirmities render the provision in question null and void.

"For the love of money is the root of all evil: ... " and

belonging to no one in particular, i.e. public funds,

prcJVide an even greater temptation for misappropriation

and embezzlement. This, evidently, was foremost in the

minds of the framers of the constitution in meticulously

prescribing the rules regarding the appropriation and

disposition of public funds as embodied in Sections 16 and

18 of Article VIII of the 1973 Constitution. Hence, the

26

conditions on the release of money from the treasury [Sec.

18(1)]; the restrictions on the use of public funds for public

purpose [Sec. 18(2)]; the prohibition to transfer an

appropriation for an item to another [See. 16(5) and the

requirement of specifications [Sec. 16(2)], among others,

were all safeguards designed to forestall abuses in the

expenditure of public funds. Paragraph 1 of Section 44 puts

all these safeguards to naught. For, as correctly observed by

petitioners, in view of the unlimited authority bestowed

upon the President, " ... Pres. Decree No. 1177 opens the

floodgates for the enactment of unfunded appropriations,

results in uncontrolled executive expenditures, diffuses

accountability for budgetary performance and entrenches

the pork barrel system as the ruling party may well expand

[sic] public money not on the basis of development

priorities but on political and personal expediency." The

contention of public respondents that paragraph 1 of

Section 44 of P.D. 1177 was enacted pursuant to Section

16(5) of Article Vlll of the 1973 Constitution must perforce

fall tlat on its face. (Emphasis supplied)

Petitioners trust that the Honorable Court will arrive at the same

conclusion that it arrived at in the said case and likewise proclaim:

The nation has not recovered from the shock. and

worst, the economic destitution brought about by the

plundering of the Treasury by the deposed dictator and his

cohorts. A provision which allows even the slightest

possibility of a repetition of this sad experience cannot

remain written in our statute books.

Even if, for the time being, the wielder of such power, Respondent

President Benigno Simeon C. Aquino Ill appears to be a benign entity-

no pun

E. THE USE OF THE DAP FUNDS TO AUGMENT THE PROVISIONS OF

THE GENERAL APPROPRIATIONS ACT OF 2013 WHICH ARE IN THE

NATURE OF LUMP SUM DISCRETIONARY APPROPRIATIONS SUCH AS

UNDER TITLE XXXV!ll OF RA. NO. 10352 ON THE CONTINGENCY

FUND, UNDER TITLE XXXVJI ON THE CALAMITY FUND, UNDER TITLE

XLV ON THE UNPROGRAMMED FUND, UNDER TITLE XXXV ON

BUDGETARY SUPPORT FOR GOCCS, THE PRIORITY DEVELOPMENT

ASSISTANCE FUND AND SUCH OTHER SPECIAL PURPOSE FUNDS IS

UNCONSTITUTIONAL FOR BEING CONTRARY TO SECTION 25 (1)

ARTICLE VI OF THE CONSTITUTION IN RELATION TO THE PROVISIONS

OF P.D. NO. 1177 AND THE ADMINISTRATIVE CODE OF 1987.

27

However, it is in the declaration of unconstitutionality of lump

sum discretionary appropriations that a more accountable, effective and

responsive public spending can be achieved.

Undoubtedly, the abolition of PDAF, DAP and other lump sum

discretionary appropriations, whether via congressional amendment,

the Honorable Court's declaration of unconstitutionality of the

questioned appropriations, by the executive's non-inclusion of the

questioned appropriations in future budgets, or even via the people's

initiative being proposed for such purpose, will be a big step in leading

government budgeting towards a more democratic, less discretionary

and more accountable system.

But if the process stops at that point, all that we may have

achieved is to move the funds from one hand into the other, to transfer

the money from the PDAF to DAP and yet leave the President with

gargantuan funds for what is essentially discretionary spending.

For that will certainly be the effect of the abolition or declaration

of unconstitutionality of the lump sum discretionary funds in the GAA of

2013, the PDAF and DAP included.

Petitioners are not about to let such important milestone in the

country's history go to waste.

Petitioners respectfully submit that insofar as the DAP funds were

used to "augment" provisions of the General Appropriations Act of 2013

that are in the nature of lump sum discretionary appropriations -- such

as under Title XXXVIll on the Contingency Fund, under Title XXXVII on

the Cala'11ity Fund, under Title XLV on the Unprogrammed Fund, under

Title XXXV on Budgetary Support for GOCCs, under Title XLV on the

Priority Development Assistance Fund and such other special purpose

funds - it is illegal and unconstitutional considering that the lump sum

discretilnary appropriations are contrary to Section 25 (1) Article VI of

the Constitution in relation to the Administrative Code of 1987.

The constitutional provision states:

Sec. 25 (1) The Congress may not increase the

appropriations recommended by the President for the

operation of the Government as specified in the budget. The

form, content, and manner of preparation of the budget

shall be prescribed by law. (Emphasis supplied)

While the foregoing authorizes the enactment of a law governing

the "form, content, and manner of preparation of the budget," Section 25

28

(5) and Section 27 (2) both make reference to "item" or "items" m

relation to appropriations, among others.

In the constitutional sense, it may be said that appropriations

come only by way of item or items, subject to the veto power of the

President. But as to what these item or items look like has not been

made clear in the Constitution but was to be "prescribed by law."

Pursuant thereto, the Administrative Code of 1987, specifically

the Book VI thereof on National Government Budgeting, was

promulgated by then President Corazon C. Aquino. Before the

promulgation of the Administrative Code of 1987, the governing law

was Presidential Decree No. 1177 entitled "REVISING THE BUDGET

PROCESS IN ORDER TO INSTITUTIONALIZE THE BUDGETARY

INNOVATIONS OF THE NEW SOCIETY." With the promulgation of the

latter Jaw, the provisions of P.D. No. 1177 inconsistent with the

Administrative Code of 1987 were repealed or modified accordingly.

Under the Administrative Code of 1987, the item or items

mentioned under Section 25 (5) and Section 27 (2) Article VI of the

Constitution has been operationalized to refer to "programs and

projects." The provision

32

of the Administrative Code of 1987 states:

SEC. 23. Content of the General Appropriations Act. - The

General Appropriations Act shall .be presented in the

form of budgetary pmgrams and projects for each

ggency of the government, with the corresponding

fWpropriations for each program and project, including

statutory provisiOns of specific agency or general

applicability. The General Appropriations Act shall not

contain any itemization of personal services which shall be

prepared by the Secretary after enactment of the General

Appropriations Act, for consideration and approval of the

President. (Emphasis supplied)

Section 24 of the same law refers to a prohibition in increasing

"the appropriation of any project or program of any department,

bureau, 'agency or office of the Government" but allows a "reduction in

the proposed appropriation for a project or program."

Thus, for appropriations to be valid, it must relate to either a

"program" or a "project" "for each agency of the government." A

"Program" has been defined as referring "to the functions and activities

-----------

3

' Section 23, Chapter 4, Book VI.

29

necessary for the performance of a maJor purpose for which a

government agency is established."33

On the other hand, a "Project means a component of a program

covering a homogenous group of activities that results in the

accomplishment of an identifiable output."3

4

An example of the operationalization of the foregoing terms is the

budget for the Department of Public Works and Highways for 2013

where the following major programs and projects, with the total

appropriations for each, appear, to wit:

A. PROGRAMS

I. General Administration and

Support

a. General Administration and

Support Services

P1,570,957,000.00

II. Support to Operations P837,460,000.00

a. Policy Formulation, Program Planning and Standards Development

b. Regional Support (Planning and Design, Construction, Maintenance

and Material Quality Control and Hydrology Divisions)

c. Operational Support for the

Maintenance and Repair of Infrastructure Facilities and Other Related

Activities

Ill. Operations

Total Programs

B. PROJECT (s)

P8,762,079,000.00

P11,178,496,000.00

I. Locally-Funded Project (s) P120,614,091,000.00

a. National Arterial and Secondary National Roads and Bridges (with

sub-appiopriations for national Arterial and Secondary for preventive

maintenance, rehabilitation/upgrading and to address Critical

bottlenecks of roads and bridges per district engineering district

nationwide)

b. Flood and Drainage Projects

c. Feasibility Study /Project Development/Preliminary and Detailed

Engineehng

d. Payments of Right-of-Way (ROW) and Contractual Obligations

e. Water Supply jSeptage & Sewerage/Rain Collectors

f. Various Infrastructure Including Local Projects

g. Public" Private Partnership Strategic Support Fund

II. Foreign Assisted Project (s) P15,724,946,000.00

33

Section 2 (12), Chapter 1, Book VI, Administrative Code of 1987.

34

Section 2(13}, Chapter 1, Book VI, Administrative Code of 1987.

30

a. Highways (Roads and Bridges} Projects

b. Flood Control Projects

Total Projects

TOTAL NEW APPROPRIATIONS

P144,339,037,000.00

P155,517,533,000.00

On the other hand, the lump sum discretionary appropriations

contains no programs or projects, merely purposes. The Contingency

Funds provision under the GAA of 2013 contains the following:

XXXVIII. CONTINGENT FUND

Fund subsidies for contingencies--------- Pl,OOO,OOO,OOO

A. PURPOSE (S)

1. Fund Subsidies for Contingencies XXX

Likewise, the Unprogrammed Funds appropriation did not

identify programs and projects but enumerated only the purposes to

which the funds may be devoted, to wit:

XLV. UNPROGRAMMED FUND

For fund requirements in accordance with the purposes

indicated hereunder--------- P117,54B,371,000

A. PURPOSE(S)

1. Budgetary Support to Government-Owned and/or

Controlled Corporations

2. Support to Foreign-Assisted Projects

3. General Fund Adjustments

4. Support for Infrastructure Projects and Social Programs

5. AFP Modernization Program

6. Debt Management Program

7. Payment of Total Administrative Disability Pension

8. People's Survival Fund

The same may be said of the other lump sum discretionary

appropriations where only the purposes to which the funds were to be

used were specified and not specific programs or projects of the

agencies involved.

Thus, these lump sum discretionary appropriations, in so far as

these did not follow the "form, content and manner of preparation of the

budget" for its failure to specify "budgetary programs and projects for

each agency of the government" are unconstitutional and illegal.

31

ALLEGATIONS IN SUPPORT OF PRAYER FOR TEMPORARY

RESTRAINING ORDER

Petitioners replead and incorporate the foregoing discussion and

further state:

As has been amply demonstrated in the foregoing discussion,

Respondents' Disbursement Acceleration Program is unconstitutional

and illegal and the continued release of public funds pursuant thereto

constitutes grave and irreparable injury on the part of Petitioners as

taxpayers, including all other taxpayers, who have the right to expect

that government money be use only for legal and constitutional

purposes.

Considering also that Petitioners are asserting a public right as a

Filipino citizen in the proper observance of the law and the Constitution,

the continued implementation of the DAP likewise violates such public

right being asserted by the Petitioners in this case.

Petitioners are entitled to the reliefs demanded under this

Petition, part of which reliefs is the issuance of a restraining order to

enjoin Respondents from further implementing the DAP and releasing

funds pursuant thereto.

Petitioners are willing to post a bond in the amount to be fixed by

the Honorable Court conditioned on the payment by Petitioners of

damages that may be sustained by Respondents by virtue of the

issuance of the temporary restraining order if the Honorable Court