Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Case15 - 2007 PDF

Uploaded by

Ana Di JayaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Case15 - 2007 PDF

Uploaded by

Ana Di JayaCopyright:

Available Formats

The

n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l

of

m e dic i n e

case records of the massachusetts general hospital

Founded by Richard C. Cabot Nancy Lee Harris, m.d., Editor Eric S. Rosenberg, m.d., Associate Editor Jo-Anne O. Shepard, m.d., Associate Editor Alice M. Cort, m.d., Associate Editor Sally H. Ebeling, Assistant Editor Christine C. Peters, Assistant Editor

Case 15-2007: A 20-Year-Old Woman with Asthma and Cardiorespiratory Arrest

Michael E. Wechsler, M.D., M.M.Sc., Jo-Anne O. Shepard, M.D., and Eugene J. Mark, M.D.

Pr e sen tat ion of C a se

A 20-year-old woman with asthma was taken to the emergency room of another hospital because of cardiorespiratory arrest. The patient had had severe asthma since childhood. She was born after a normal pregnancy and delivery to a teenaged, single mother, who smoked three packs of cigarettes per day during pregnancy and during the patients childhood. Asthma developed at the age of 4 years, and exacerbations occurred frequently thereafter, triggered by cold air, hot humid air, physical activity, respiratory infections, anxiety, and exposures to paint and to cats and birds that were kept in her home or the homes of relatives. Attacks often occurred at night or in the early morning. A timeline of medical therapy for asthma is shown in Table 1, and the results of pulmonary-function tests are shown in Table 2. During testing, the results improved after bronchodilator therapy. She was followed by pediatricians and specialists in pulmonary medicine; however, she repeatedly missed outpatient follow-up appointments and visited emergency rooms on many occasions because of exacerbations. She was inconsistent in her use of inhalers and oral medications; she used inhaled bronchodilators up to 10 times per day when she had symptoms. At the age of 15 years, she told hospital staff that she rarely took her medications regularly. Involvement by the Department of Social Services was requested because of noncompliance with treatment, and the patients mother was counseled to stop smoking, but these interventions were unsuccessful. Visiting-nurse assessments of the patients residence for possible allergens were scheduled, but despite multiple attempts, the assessments were not performed because of the familys absence from the home. Oxygen desaturation occurred during some asthma episodes, including an episode of status asthmaticus at the age of 8 years, with an oxygen saturation of 80% while the patient was breathing ambient air and had a respiratory rate of more than 50 breaths per minute. She was admitted to this hospital every few months because of asthma and pneumonia, occasionally to the pediatric intensive care unit. Tracheal intubation was never required. Peripheral-blood eosinophilia was never documented. Immunoglobulin E levels were not measured. Five months before this admission, 1 day after receiving treatment in an emergency room for an asthma flare, the patient was seen at an urgent care facility because of shortness of breath, cough productive of white sputum, chills, and wheezn engl j med 356;20 www.nejm.org may 17, 2007

From the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Womens Hospital (M.E.W.); the Departments of Radiology (J.O.S.) and Pathology (E.J.M.), Massachusetts General Hospital; and the Departments of Medicine (M.E.W.), Radiology (J.O.S.), and Pathology (E.J.M.), Harvard Medical School all in Boston. N Engl J Med 2007;356:2083-91.

Copyright 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society.

2083

Downloaded from www.nejm.org on May 19, 2007 . Copyright 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The

n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l

of

m e dic i n e

Table 1. Timeline of Asthma Therapies. Medications Administered on Admission (to Emergency Department or Hospital) Epinephrine (subcutaneous) Aminophylline (intravenous) Methylprednisolone (intravenous)

Age Range 410 yr

Medications Taken at Home Metaproterenol Albuterol by nebulizer and metered-dose inhaler Theophylline Isoetharine by nebulizer Cromolyn sodium inhaler Beclomethasone inhaler Tapered prednisone (514 days) Albuterol by nebulizer and metered-dose inhaler Ipratropium bromide by nebulizer Salmeterol xinafoate inhaler Fluticasone propionate metered-dose inhaler Budesonide inhaler Tapered prednisone (514 days) Montelukast sodium tablets Beclomethasone inhaler Albuterol metered-dose inhaler Albuterol and ipratropium bromide by nebulizer Theophylline Salmeterol xinafoate inhaler Fluticasone propionate metered-dose inhaler Montelukast sodium tablets Prednisone (560 mg daily)

1015 yr

Epinephrine (subcutaneous) Terbutaline sulfate (subcutaneous or intravenous)

1520 yr

Epinephrine (subcutaneous or intravenous) Dexamethasone Terbutaline (subcutaneous or intravenous) Magnesium sulfate (intravenous)

ing of 2 days duration, despite around-the-clock inhalational treatments with nebulized albuterol (2.5 mg) and nebulized ipratropium (0.5 mg). Her other asthma medications were salmeterol (one puff twice daily), fluticasone propionate delivered as an aerosol (220 g per puff, at a dose of two puffs with a spacer adaptor, twice daily), prednisone (5 mg every other day), and albuterol with the use of a metered-dose inhaler (two puffs four times daily as needed). The patient had a history of obesity, gastroesophageal reflux for which she took esomeprazole, depression, wrist fractures after a fall, a parietal skull fracture after an assault, chickenpox, and pinworms. Childhood vaccinations had been given but had been delayed because of missed appointments. She had no allergies to medications. She was of South Asian, Scottish, and Dutch ancestry. She had missed many months of school because of asthma and had left school after the eighth grade at the age of 15 years. She gave birth to a child at the age of 19 years and lived with the child, her mother, and her half-siblings. She told some caregivers that she smoked cigarettes but also told many others that she did not smoke. The patients mother and other maternal relatives had asthma and eczema, and there was a family history of diabetes mellitus. Her two half-siblings

2084

were healthy; her fathers medical history was not known. On physical examination at the urgent care facility, the patient was in moderate respiratory distress. The blood pressure was 152/62 mm Hg, the pulse 120 beats per minute, and the temperature 37.4C; the respirations were 28 per minute, and the oxygen saturation was 90 to 91% while the patient was breathing ambient air. At her request, a peak-flow measurement was not performed. The body habitus was cushingoid, and there were diffuse wheezes in both lungs, without rales or rhonchi. There was no digital clubbing or cyanosis. The remainder of the examination was normal. A chest radiograph revealed consolidation in the right middle lobe and patchy opacity in the left upper lobe. A combination solution of albuterol and ipratropium was administered by nebulizer twice, and she was discharged home while receiving prednisone (60 mg daily, with instructions to taper the dose), her other medications, and a 5-day course of azithromycin. Approximately 8 weeks before admission, the patient was seen in the emergency room of a local hospital because of respiratory symptoms. Cla rithromycin was prescribed, but the symptoms worsened; several days later, a chest radiograph revealed a left-upper-lobe and perihilar infiltrate

n engl j med 356;20 www.nejm.org may 17, 2007

Downloaded from www.nejm.org on May 19, 2007 . Copyright 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

case records of the massachuset ts gener al hospital

suggestive of pneumonia. Ceftriaxone was prescribed and admission to the hospital was recommended, but she left against medical advice to care for her child. One week later, she saw her primary care physician, who prescribed levofloxacin. Three days later, she was seen at an urgent care facility because of persistent symptoms. At that time, she was taking prednisone (30 mg) daily and albuterol as needed. Prednisone (30 mg) was administered orally, and a combination of albuterol and ipratropium was given by nebulizer. She was instructed to take prednisone (60 mg) daily, tapering to a final dose of 10 mg every other day. A follow-up visit and an appointment with a pulmonary specialist were scheduled, but the patient did not keep the appointments. During the next weeks, the patient visited emergency departments four or five times because of acute symptoms of asthma, and she made numerous phone calls to her primary care physician, requesting refills of her medications. The physician became aware that the patient was receiving asthma medications from several different providers. In the early hours of the morning of admission, the patients mother noted that the patient was awake and using a nebulizer, as she did frequently. When her mother next saw her, approximately 2 hours later, the patient was lying on the floor, unresponsive, without spontaneous respirations or pulse. The patients mother called emergency medical services (EMS). On examination by EMS providers, the patient was cold, cyanotic, and in asystole. The trachea was intubated, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation was initiated. Epinephrine (1 mg) and atropine (1 mg) were administered intravenously; this was repeated twice without response. The patient was taken to the emergency room of another hospital, arriving 25 minutes later while cardiopulmonary resuscitation was in progress. She remained in asystolic cardiac arrest, despite aggressive resuscitation attempts. She was pronounced dead 10 minutes after arrival. The body was transferred to this hospital, and an autopsy was performed.

Table 2. Results of Pulmonary-Function Tests.* Measure 7 Yr FVC (liters) FEV1 (liters) FEF25 of FVC (liters/sec) FEF75 of FVC (liters/sec) FEF2575 of FVC (liters/sec) (44) Normal Normal Age 11 Yr 2.79 (125) 2.00 (100) 3.29 (73) 0.62 (46) 1.45 (56) 1.71 (58) 2.49 (96) 18 Yr

actual value (% of predicted value)

* FVC denotes forced vital capacity in liters, FEV1 forced expiratory volume in the first second, FEF25 maximum forced expiratory flow rate when 25% of the FVC has been exhaled, FEF75 maximum forced expiratory flow rate when 75% of the FVC has been exhaled, and FEF2575 maximum forced expiratory flow rate between 25% and 75% of the FVC exhaled.

Differ en t i a l Di agnosis

Dr. Michael E. Wechsler: May we review the imaging studies? Dr. Jo-Anne O. Shepard: Chest radiographs (Fig. 1A and 1B) obtained 17 months before her death, on one of the patients multiple visits for asthma exacerbations, show pneumomediastinum, with air

tracking into the neck. On the lateral view (Fig. 1B) there is a tiny anterior pneumothorax. The pneumothorax results from the Macklin effect, in which a peripheral alveolus ruptures and the air tracks centrally along the interstitium into the mediastinum and soft tissues. These features are typical of asthma. Bilateral focal consolidations are present, representing pneumonia. Dr. Wechsler: This case highlights the problem of asthma-associated morbidity and mortality, with more than 4000 deaths from asthma occurring annually in the United States.1 This patients multiple hospitalizations and emergency room visits exemplify the annual 500,000 asthma-related hospitalizations and 2 million emergency room visits that account for $16 billion per year spent for asthma treatment2 and the millions of asthmarelated lost work and school days. This patient dropped out of school because of the hold that asthma had on her life. There are many possible causes of death in a patient with asthma in whom respiratory failure develops. Patients with corticosteroid-induced chronic immunosuppression are predisposed to life-threatening infections, anaphylaxis, and acute hypersensitivity reactions; however, this patient did not have a history or laboratory evidence to suggest any of these diagnoses, nor did she have any underlying cardiac disease. She did not have a history of eosinophilia or other major clinical manifestations of eosinophilic pneumonia or the Churg Strauss syndrome. She had nearly all the risk factors for life-threatening asthma and death from asthma (Table 3), except for aspirin sensitivity and older age. Although not a consistent cigarette smoker, she had some history of smoking and

2085

n engl j med 356;20 www.nejm.org may 17, 2007

Downloaded from www.nejm.org on May 19, 2007 . Copyright 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The

n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l

of

m e dic i n e

33p9

Figure 1. Radiographic Images. RETAKE 1st Wechsler AUTHOR ICM Posterior anterior (Panel A) and lateral (Panel B) chest radiographs obtained 17 months 2nd before the patients death REG F FIGURE Fig 1A,B show pneumomediastinum (Panel A, large arrows) and an anterior pneumothorax (Panel B, large arrow). Bilateral 3rd CASE TITLE Revised focal consolidations (Panels A and B, small arrows) are consistent with pneumonia. EMail

Enon FILL

ARTIST: mleahy

exposure to secondhand smoke both in utero and PLEASE egories of both moderate and severe persistent AUTHOR, NOTE: Figure mechanihas been redrawn and type has been reset. during childhood. She had not required disease. Whereas all patients with asthma should Please check carefully. cal ventilation, but she had been hospitalized many avoid or control factors that trigger attacks, patients times. Therefore, I believe that this asthma should also use controller 35620 had with persistent JOB: patient ISSUE: 5-17-07 status asthmaticus with resultant fatal asthma. medication daily to control airway inflammation Why did this patient die from asthma? The (e.g., inhaled corticosteroids) and, as the severity answer may lie with the treatment plan, the com- increases, escalate therapy appropriately. Asthma pliance of the patient with the plan, and the inher- guidelines from 2006 focus on maintenance of ent severity of her disease (so severe that no mea- control, reflecting an understanding that asthma sure taken could have saved her). Each of these severity involves not only the severity of the unfactors must be addressed in this case. derlying disease but also its responsiveness to treatment, and that severity is not an unvarying feature of an individual patients asthma but may Dis cus sion of M a nage men t 4 change over months or years. To address growing concern about increased asthInhaled corticosteroids, which had been inma-related morbidity and mortality, in the late cluded in this patients regimen early in her care, 1990s the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for- are the cornerstone of these recommendations. mulated the National Asthma Education and Pre- There is evidence that inhaled corticosteroids not vention Program, establishing guidelines for the only improve lung function and symptoms but also management of asthma.3 The NIH recommended may prevent deaths from asthma.5 Short-acting stratification of patients according to the severity beta-agonists may be used in the short term to of asthma (mild intermittent, mild persistent, mod- relieve symptoms; however, if there is poor astherate persistent, and severe persistent disease) and ma control despite the use of inhaled corticosteimplementation of treatment algorithms. At differ- roids, as in this case, other controller therapies, ent times, this patients condition fell into the cat- such as long-acting beta-agonists, leukotriene

2086

n engl j med 356;20 www.nejm.org may 17, 2007

Line H/T Combo

4-C H/T

SIZE 33p9

Downloaded from www.nejm.org on May 19, 2007 . Copyright 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

case records of the massachuset ts gener al hospital

modifiers, cromolyn, theophylline, or even systemic corticosteroids should be added to the regimen. All these medications were prescribed at various times for this patient, but not on a consistent basis. When the disease is controlled, the doses or number of controller medications may be reduced. This patients asthma rarely, if ever, appeared to be sufficiently controlled to allow the tapering of medications. Patient education is essential at every step of asthma management, and patients should continue to monitor their disease subjectively (i.e., assessing symptoms) and objectively (using peakflow meters or spirometry). Although such approaches were attempted in this case, they were unsuccessful.

Managing Severe Asthma

Table 3. Risk Factors for Life-Threatening Asthma and Death from Asthma. Long duration of asthma Poor control of asthma Systemic dependence on corticosteroids Noncompliance with medication regimen Psychosocial factors Poor socioeconomic conditions Inconsistent medical follow-up Delayed medical care Older age Cigarette smoking Aspirin sensitivity Prior hospitalization for asthma Prior use of mechanical ventilation

Both the patient and the physician have responsibilities in the management of severe asthma. However, a major problem in the control of asthma is that much of the responsibility lies with the patient.

Adherence to Controller Therapy and Appropriate Technique

sis, cataracts, glaucoma, and adrenal suppression. None of these complications were apparent in this case.

Consistent Physician Care

Even if a medication is shown to be effective in ideal circumstances, as in a clinical trial, its effectiveness in practice requires adherence to a prescribed regimen; for medication to be effective, patients must take it regularly as it is meant to be taken. Like this patient, nearly 70% of patients with severe asthma do not refill prescriptions for inhaled corticosteroids,6,7 and many use inhalers incorrectly. Poor adherence to asthma medications may be due to lack of an immediate benefit, the patients preference for pills rather than inhalers, suboptimal results because the patients technique of use is suboptimal, cost, inconvenience, and lack of education by health care providers. Many patients, like this one, are children or adolescents who may have problems accepting the facts of their illness and the necessity for adhering to an onerous treatment regimen. The cost of the medications may be an issue, since asthma is increasingly prevalent among economically disadvantaged, inner-city children for whom access to medications is often a difficulty. Physicians clearly worked with this patient to maximize adherence and to explain the importance of taking medications daily. Adverse effects of medications can also lead to poor adherence. For example, inhaled corticosteroids can cause dysphonia, oral thrush, osteoporo-

Consistency of health care providers was a problem in this case, because no single physician could appreciate the full scope of this patients multiple presentations for worsening asthma. During the last 5 years of her life, she saw many different primary care doctors, pulmonologists, and allergists. She went to different clinics and emergency rooms many times, each time seeing different physicians. This fragmentation of care could have resulted in a missed opportunity for one physician to detect her clinical deterioration during a period of weeks or months and to provide support.

Education and Warning Signs

Education of patients about triggers and warning signs of severe attacks is critical to the management of severe asthma. This patient knew what provoked her asthma (e.g., cold air and hot, humid air), and she avoided going outside in winter. We do not know whether she had a peak-flow meter with which to assess the degree of airflow obstruction or whether she was aware of the severity of her disease. There was no record of allergy testing.

Other Medical Options

This patients physicians had tried virtually all available therapies to control her disease (Table 1), including new treatments such as leukotrienereceptor antagonists. Novel therapies are now available that might have helped control this patients

2087

n engl j med 356;20 www.nejm.org may 17, 2007

Downloaded from www.nejm.org on May 19, 2007 . Copyright 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The

n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l

of

m e dic i n e

asthma. For instance, omalizumab, a monoclonal antibody against IgE, prevents IgE from binding to mast cells and other inflammatory cells, thereby preventing the release of inflammatory mediators. Its use may permit a lower dose of corticosteroids and may reduce the frequency of exacerbations, which, in turn, could reduce the number of outpatient and emergency room visits and hospitalizations among patients with moderate-to-severe asthma.8,9 Tumor-necrosis-factor (TNF) inhibitors have also been investigated in asthma. TNF is a proinflammatory cytokine affecting adhesion, migration, activation, and proliferation of many types of cells. It is increased in the bronchoalveolar-lavage fluid of patients with asthma, and preliminary data suggest that TNF inhibitors may significantly improve lung function and symptoms in patients with severe asthma.10

Factors Contributing to Poor Outcomes Despite Optimal Medication Regimens

eosinophilia or vasculitis, which are characteristic of the last three disorders. Although IgE levels may be elevated in these conditions, IgE testing was not performed.

Pharmacogenetics and the Efficacy of Asthma Therapies

Several factors can result in poor outcomes despite optimized medication regimens. Exposure to environmental exacerbating factors such as dust, smoke, or cockroaches may impair responsiveness to specific therapies. Caregivers made attempts to modify the home environment of this patient when she was a child, but they were unsuccessful. We do not know whether the issue of environmental factors had been raised with the patient during recent years or whether she would have been more compliant as a young adult than her mother had been during the patients childhood. Coexisting diseases can also impair asthma outcomes despite optimal medication regimens. This patient had evidence of gastroesophageal reflux disease, a condition that may provoke or worsen symptoms of asthma. She used a protonpump inhibitor, but it would have been important to ascertain that the reflux was adequately controlled and was not contributing to asthma exacerbations. Chronic sinusitis and postnasal drip may also exacerbate asthma. This patient had a history of multiple episodes of pneumonia, which resulted in the exacerbation of symptoms, and infection certainly could have contributed to her respiratory failure and death. Some conditions mimic severe asthma. This patients fleeting pulmonary infiltrates and airflow obstruction could suggest diagnoses such as cystic fibrosis, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, bronchocentric granulomatosis, or the ChurgStrauss syndrome. She had no history of

2088

This patient may be one of the many patients whose asthma is unresponsive to current standard therapies. As many as 40% of patients do not have a response to inhaled corticosteroids,11-13 and perhaps even a higher proportion do not have a response to leukotriene modifiers. Heterogeneity of the underlying biology may affect responsiveness to specific therapies. Symptoms may be driven by perturbations in corticosteroid, leukotriene, IgE, or beta-adrenergic pathways or even in other pathways yet to be identified; each of these pathways may be modulated by different medications, so therapies should ideally be tailored to the underlying pathogenesis. Similarly, asthma may be mediated by eosinophils or, in the case of severe asthma, by neutrophils. TNF may have a role, and natural killer cells may be principal effector cells.14 Since it is currently not possible to identify the specific pathway involved in a given patients asthma, we prescribe on the basis of trial and error an approach that, as this case shows, is not always successful. Pharmacogenetics, the study of how genetic differences influence variability in therapeutic and adverse responses to drugs, may predict some of the heterogeneity of responses to asthma treatments. A mutation in a specific pathway may cause or prevent a response to a medication aimed at that pathway or cause an adverse reaction. In asthma, genetic factors may affect responses to beta-agonists, leukotriene modifiers, and inhaled corticosteroids.15 In particular, a common variant in the gene coding for the 16th amino acid of the betaadrenergic receptor is associated with a decline in lung function and asthma exacerbations in patients receiving either short- or long-acting betaagonists.16-19 Among patients with asthma, this polymorphism occurs in one sixth of white patients and up to one quarter of black patients. Although genetic testing is not routinely available, caregivers should be aware of the potential genotype-specific effects of long-acting beta-agonists and their potential association with bad outcomes, including death, in patients with asthma.20 Although these therapies are helpful for the majority of patients with asthma, those taking the long-acting beta-agonists salmeterol or formoterol

n engl j med 356;20 www.nejm.org may 17, 2007

Downloaded from www.nejm.org on May 19, 2007 . Copyright 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

case records of the massachuset ts gener al hospital

have an increased risk of both exacerbations and asthma-related death, as compared with those not receiving these medications.21 Although we do not have any genotypic information for this patient, we know she took salmeterol, and a pharmacogenetically mediated deleterious effect of this longacting beta-agonist could have played a role in her deteriorating condition and death. A large, prospective, genotype-stratified trial investigating whether long-acting beta-agonists cause such adverse effects, which is currently being conducted by the Asthma Clinical Research Network of the NIH, may answer this question.

Use of Biomarkers in Asthma Control

teristic of fatal asthma.26-31 The gross pathological features of fatal asthma may be more dramatic than the microscopical findings. Pneumothorax may occur as a complication of the disease and is a potential cause of death; its documentation at autopsy requires opening the chest under a water seal. No pneumothorax was found in this patient. The lungs were hyperinflated, with rounded contours when removed from the body (Fig. 2A). Ex-

This patient had a normal forced expiratory volume in 1 second, but she clearly had severe asthma, as shown by the long duration and frequency of her symptoms, frequent use of quick-relief inhalers, and missed work and school. An important area of asthma research is the use of biomarkers to assess airway inflammation and guide therapy for patients with asthma. Adjustment of asthma medications on the basis of assessment of sputum eosinophils, exhaled nitric oxide, and airway hyperreactivity can reduce asthma exacerbations22-25 and also potentially minimize treatment-related side effects.

DR . MICH A EL E . W ECHSL ERS DI AGNOSIS

Fatal asthma.

Pathol o gic a l Dis cus sion

Dr. Eugene J. Mark: The diagnosis of fatal asthma falls within the purview of both the hospital pathologist and the forensic pathologist, the latter because of the possibility that asthma may explain sudden unexpected death. Factors for the forensic pathologist to consider in determining whether asthma was the cause of sudden, unwitnessed death include a history of severe attacks, the existence and location of therapeutic drugs and inhalers that could have been used by the patient, and gross and microscopical evidence of acute and chronic asthma. At autopsy, the common differential diagnosis of the cause of death includes asphyxia from other causes, anaphylactic reaction, coexistent pulmonary emboli, and coronary artery disease. In this case, the autopsy findings were charac-

Figure 2. Autopsy Findings. The right lung is hyperinflated this gross photograph taken before the RETAKE 1st AUTHOR in Wechsler ICM lung was removed from the body (Panel A); a depressed polygonal lobule 2nd REG F FIGURE 2 a_e 3rd emphy(arrow) contrasts with the hyperinflated adjacent lung. Mediastinal CASE TITLE Revised sema is present (Panel B), with bubbles of air in the pericardial fat (arrows). EMail Line 4-C A small bronchus is filled with mucus and sloughed epithelial SIZE cells (Panel Enon ARTIST: mst H/T H/T C, hematoxylinFILL and eosin). A terminal bronchiole (Panel 22p3 D, hematoxylin Combo and eosin) contains hypertrophic smooth muscle AUTHOR, PLEASE NOTE:(arrow). Numerous eosinophils are presentFigure in thehas pulmonary interstitium (Panel E, hematoxylin and been redrawn and type has been reset. Please check carefully. of Dr. Pavan Auluck, Deeosin). (Photographs in Panels A and B courtesy partment of Pathology, Massachusetts General Hospital.)

JOB: 35620 ISSUE: 05-17-07

n engl j med 356;20 www.nejm.org may 17, 2007

2089

Downloaded from www.nejm.org on May 19, 2007 . Copyright 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The

n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l

of

m e dic i n e

amination of a cut section showed that the parenchyma protruded above the cut edge of the visceral pleura. When left lying on a dissecting table, the lungs deflated only slowly. In some cases it may be difficult to inflate the lungs with formalin through the bronchial tree because of bronchiolar obstruction, which was the case with this patients lungs. Pneumomediastinum was present, with interstitial emphysema in fibroadipose tissue (Fig. 2B). Mucus plugs in bronchi are a frequent finding; the mucus may protrude from the cut end of a bronchus. Microscopically, bronchi and bronchioles were distended by mucus (Fig. 2C), and lymphocytes, neutrophils, and mast cells were present in the bronchiolar mucosa. The bronchial basement mem brane was thickened, and airway smooth-muscle hypertrophy caused bronchiolar narrowing or subtotal occlusion (Fig. 2D).32 Signs of chronic scarring, resulting in constrictive bronchiolitis, were present, with small focal scars representing obliterated bronchioles. Eosinophils are an inconsistent finding in fatal asthma33,34; they may be present in the bronchial lumen, in alveoli, or in the pulmonary interstitium, as in this case (Fig. 2E).35,36 There were no pulmonary emboli, and

References

1. Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Anderson

the remainder of the autopsy disclosed no evidence of coronary artery disease or other abnormalities. A Physician: The patients mother noted that the patient was using a nebulizer shortly before she died. Could that have contributed to her death? Dr. Wechsler: Frequent use of albuterol was unlikely to have caused her death unless there was an underlying cardiac abnormality. The frequent use of nebulized beta-agonists was an indicator of the poor control of her asthma, which ultimately caused her death. We attempted a postmortem analysis of tissue from this patient for evidence of the deleterious mutation in the beta-adrenergic receptor, but we were unable to extract DNA of sufficient quality.

A nat omic a l Di agnosis

Status asthmaticus with hyperinflated lungs, pleural and pericardial interstitial emphysema, mucus plugging, bronchiolar scarring, and eosinophilic pneumonitis.

Dr. Wechsler reports receiving consulting fees or advisoryboard fees from Genentech, Merck, Pfizer, Tanox, and Critical Therapeutics and lecture fees from Novartis, Genentech, and Merck, and serving as an investigator in a trial of a bronchial thermoplasty system sponsored by Asthmatx. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

RN, Scott C. Deaths: final data for 2002. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2004;53:1-115. 2. American Lung Association. Trends in asthma morbidity and mortality. New York: American Lung Association, Epidemiology & Statistics Unit, Research and Scientific Affairs, 2004. 3. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program: guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. Expert Panel report 2. Bethesda, MD: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 1997. (NIH publication no. 97-4051.) 4. Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. Hamilton, ON, Canada: GINA, November 2006. (Accessed April 20, 2007, at http://www.ginasthma.org.) 5. Suissa S, Ernst P, Benayoun S, Baltzan M, Cai B. Low dose inhaled corticosteroids and the prevention of death from asthma. N Engl J Med 2000;343:332-6. 6. Drazen JM, Israel E, OByrne PM. Treatment of asthma with drugs modifying the leukotriene pathway. N Engl J Med

1999;340:197-206. [Errata, N Engl J Med 1999;340:663, 1999;341:1632.] 7. Kelloway JS, Wyatt RA, Adlis SA. Comparison of patients compliance with prescribed oral and inhaled asthma medications. Arch Intern Med 1994;154:1349-52. 8. Busse W, Corren J, Lanier BQ, et al. Omalizumab, anti-IgE recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of severe allergic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;108:184-90. 9. Soler M, Matz J, Townley R, et al. The anti-IgE antibody omalizumab reduces exacerbations and steroid requirement in allergic asthmatics. Eur Respir J 2001;18:25461. [Erratum, Eur Respir J 2001;18:73940.] 10. Berry MA, Hargadon B, Shelley M, et al. Evidence of a role of tumor necrosis factor in refractory asthma. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:697-708. 11. Malmstrom K, Rodriguez-Gomez G, Guerra J, et al. Oral montelukast, inhaled beclomethasone, and placebo for chronic asthma: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1999;130:487-95.

12. Tantisira KG, Lake S, Silverman ES, et

al. Corticosteroid pharmacogenetics: association of sequence variants in CRHR1 with improved lung function in asthmatics treated with inhaled corticosteroids. Hum Mol Genet 2004;13:1353-9. 13. Bateman ED, Boushey HA, Bousquet J, et al. Can guideline-defined asthma control be achieved? The Gaining Optimal Asthma ControL study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;170:836-44. 14. Akbari O, Faul JL, Hoyte EG, et al. CD4+ invariant T-cell-receptor+ natural killer T cells in bronchial asthma. N Engl J Med 2006;354:1117-29. 15. Wechsler ME, Israel E. How pharmacogenomics will play a role in the management of asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;172:12-8. 16. Israel E, Drazen JM, Liggett SB, et al. The effect of polymorphisms of the beta2adrenergic receptor on the response to regular use of albuterol in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;162:75-80. 17. Israel E, Chinchilli VM, Ford JG, et al. Use of regularly scheduled albuterol treat-

2090

n engl j med 356;20 www.nejm.org may 17, 2007

Downloaded from www.nejm.org on May 19, 2007 . Copyright 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

case records of the massachuset ts gener al hospital

ment in asthma: genotype-stratified, randomized, placebo-controlled cross-over trial. Lancet 2004;364:1505-12. 18. Wechsler ME, Lehman E, Lazarus SC, et al. -Adrenergic receptor polymorphisms and response to salmeterol. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;173:519-26. 19. Palmer CNA, Lipworth BJ, Lee S, Ismail T, Macgregor DF, Mukhopadhyay S. Arginine-16 beta-2 adrenoceptor genotype predisposes to exacerbations in young asthmatics taking regular salmeterol. Thorax 2006;61:940-4. 20. Nelson HS, Weiss ST, Bleecker ER, Yancey SW, Dorinsky PM. The Salmeterol Multicenter Asthma Research Trial: a comparison of usual pharmacotherpay for asthma or usual pharmacotherapy plus salmeterol. Chest 2006;129:15-26. [Erratum, Chest 2006;129:1393.] 21. Martinez FD. Safety of long-acting beta-agonists an urgent need to clear the air. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2637-9. 22. Smith AD, Cowan JO, Brassett KP, Herbison GP, Taylor DR. Use of exhaled nitric oxide measurements to guide treatment in chronic asthma. N Engl J Med 2005;352:2163-73. 23. Deykin A, Lazarus SC, Fahy JV, et al. Sputum eosinophil counts predict asthma control after discontinuation of inhaled corticosteroids. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005;115:720-7. 24. Sont JK, Willems LN, Bel EH, van Krieken JH, Vandenbroucke JP, Sterk PJ. Clinical control and histopathologic outcome of asthma when using airway hyperresponsiveness as an additional guide to long-term treatment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;159:1043-51. 25. Green RH, Brightling CE, McKenna S, et al. Asthma exacerbations and sputum eosinophil counts: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002;360:1715-21. 26. Mark EJ. Pathology of fatal asthma. In: Sheffer AL, ed. Fatal asthma. Vol. 115 of Lung biology in health and disease. New York: Marcel Dekker, 1998:127-38. 27. Houston JC, De Navasquez S, Trounce JR. A clinical and pathological study of fatal cases of status asthmaticus. Thorax 1953;8:207-13. 28. Dunnill MS. The pathology of asthma, with special reference to changes in the bronchial mucosa. J Clin Pathol 1960;13: 27-33. 29. Messer JW, Peters GA, Bennett WA. Causes of death and pathologic findings in 304 cases of bronchial asthma. Dis Chest 1960;38:616-24.

30. Rea HH, Scragg R, Jackson R, Beagle-

hole R, Fenwick J, Sutherland DC. A casecontrol study of deaths from asthma. Thorax 1986;41:833-9. 31. Hogg JC. The pathology of asthma. Chest 1985;87:Suppl:152S-153S. 32. Hossain S, Heard BE. Hyperplasia of bronchial muscle in asthma. J Pathol 1970; 101:171-84. 33. Saetta M, Di Stefano A, Rosina C, Thiene G, Fabbri LM. Quantitative structural analysis of peripheral airways and arteries in sudden fatal asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis 1991;143:138-43. 34. Sur S, Crotty TB, Kephart GM, et al. Sudden-onset fatal asthma: a distinct entity with few eosinophils and relatively more neutrophils in the airway submucosa? Am Rev Respir Dis 1993;148:713-9. 35. Carroll N, Elliot J, Morton A, James A. The structure of large and small airways in nonfatal and fatal asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis 1993;147:405-10. 36. Chetta A, Foresi A, Del Donno M, Bertorelli G, Pesci A, Olivieri D. Airways remodeling is a distinctive feature of asthma and is related to severity of disease. Chest 1997;111:852-7.

Copyright 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society.

Lantern Slides Updated: Complete PowerPoint Slide Sets from the Clinicopathological Conferences

Any reader of the Journal who uses the Case Records of the Massachusetts General Hospital as a teaching exercise or reference material is now eligible to receive a complete set of PowerPoint slides, including digital images, with identifying legends, shown at the live Clinicopathological Conference (CPC) that is the basis of the Case Record. This slide set contains all of the images from the CPC, not only those published in the Journal. Radiographic, neurologic, and cardiac studies, gross specimens, and photomicrographs, as well as unpublished text slides, tables, and diagrams, are included. Every year 40 sets are produced, averaging 50-60 slides per set. Each set is supplied on a compact disc and is mailed to coincide with the publication of the Case Record. The cost of an annual subscription is $600, or individual sets may be purchased for $50 each. Application forms for the current subscription year, which began in January, may be obtained from the Lantern Slides Service, Department of Pathology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA 02114 (telephone 617-726-2974) or e-mail Pathphotoslides@partners.org.

n engl j med 356;20 www.nejm.org may 17, 2007

2091

Downloaded from www.nejm.org on May 19, 2007 . Copyright 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- HydrotubationDocument4 pagesHydrotubationAna Di Jaya100% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Leiomyoma and Rhabdomyoma of The Vagina Vaginal MyomaDocument5 pagesLeiomyoma and Rhabdomyoma of The Vagina Vaginal MyomaAna Di JayaNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Journal of Medical Case ReportsDocument4 pagesJournal of Medical Case ReportsAna Di JayaNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Case Report: Vaginal Myomectomy For A Thirteen-Centimeter Anterior MyomaDocument4 pagesCase Report: Vaginal Myomectomy For A Thirteen-Centimeter Anterior MyomaAna Di JayaNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Pilot Evaluation of Saline Sonohysterography For Postmenopausal Bleeding With Thickened EndometriumDocument4 pagesA Pilot Evaluation of Saline Sonohysterography For Postmenopausal Bleeding With Thickened EndometriumAna Di JayaNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Efficacy of Micronised Vaginal Progesterone Versus Oral Dydrogestrone in The Treatment of Irregular Dysfunctional Uterine Bleeding: A Pilot Randomised Controlled TrialDocument5 pagesEfficacy of Micronised Vaginal Progesterone Versus Oral Dydrogestrone in The Treatment of Irregular Dysfunctional Uterine Bleeding: A Pilot Randomised Controlled TrialAna Di JayaNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hypovolemic Shock Due To Massive Edema of A Pedunculated Uterine Myoma After DeliveryDocument4 pagesHypovolemic Shock Due To Massive Edema of A Pedunculated Uterine Myoma After DeliveryAna Di JayaNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Hospital Supply Chain ManagementDocument39 pagesHospital Supply Chain ManagementFatima Naz0% (1)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Spine Care Technologies Inc. and Zober Industries Inc. Announce Strategic AllianceDocument3 pagesSpine Care Technologies Inc. and Zober Industries Inc. Announce Strategic AlliancePR.comNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Stress and Coping Styles To StudentsDocument8 pagesStress and Coping Styles To StudentsArien Kaye VallarNo ratings yet

- Slu Brochure Ay 2014-2015Document2 pagesSlu Brochure Ay 2014-2015Michael BermudoNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Edicted PG, StanDocument69 pagesEdicted PG, StanNwakpa Stanley OgbonnayaNo ratings yet

- 2019 EC 006 REORGANIZING BADAC Zone - 1Document5 pages2019 EC 006 REORGANIZING BADAC Zone - 1Barangay BotongonNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Interpretations: How To Use Faecal Elastase TestingDocument6 pagesInterpretations: How To Use Faecal Elastase TestingguschinNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Safety Data Sheet Idfilm 220 X: 1. Identification of The Substance/Preparation and The CompanyDocument4 pagesSafety Data Sheet Idfilm 220 X: 1. Identification of The Substance/Preparation and The CompanyHunterNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Risk Assessment: Severity (1, 2 or 3)Document1 pageRisk Assessment: Severity (1, 2 or 3)Ulviyye ElesgerovaNo ratings yet

- Referat Limba Engleză-Zidaroiu Ionuț-EduardDocument6 pagesReferat Limba Engleză-Zidaroiu Ionuț-EduardEduard IonutNo ratings yet

- Mobil™ Dexron-VI ATF: Product DescriptionDocument2 pagesMobil™ Dexron-VI ATF: Product DescriptionOscar GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- BISWAS Vol 3, Issue 2Document225 pagesBISWAS Vol 3, Issue 2Vinayak guptaNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Otto Gross A Case of Exclusion and Oblivion in TheDocument13 pagesOtto Gross A Case of Exclusion and Oblivion in TheVissente TapiaNo ratings yet

- Tranexamic Acid MouthwashDocument1 pageTranexamic Acid MouthwashTalal MazharNo ratings yet

- User Manual FotonaDocument103 pagesUser Manual Fotonarasheeque100% (4)

- Town Planning: Q. Identify The Problems in India Regarding Town PlanningDocument8 pagesTown Planning: Q. Identify The Problems in India Regarding Town PlanningYogesh BhardwajNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Benchmark Report 2011Document80 pagesBenchmark Report 2011summitdailyNo ratings yet

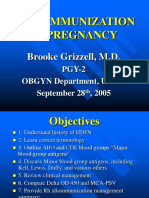

- Alloimmunization in Pregnancy: Brooke Grizzell, M.DDocument40 pagesAlloimmunization in Pregnancy: Brooke Grizzell, M.DhectorNo ratings yet

- New Trends in Mechanical VentilationDocument4 pagesNew Trends in Mechanical Ventilationashley_castro_4No ratings yet

- Hiradc Om - Talian AtasDocument57 pagesHiradc Om - Talian AtasapnadiNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- ANNEX III ASEAN GL On Limits of Contaminations TMHS V1.0 (13nov14)Document11 pagesANNEX III ASEAN GL On Limits of Contaminations TMHS V1.0 (13nov14)Bambang PriyambodoNo ratings yet

- Specialty Pharmaceutical Biotechnology Sales in Sarasota FL Resume Jeffrey MinettDocument1 pageSpecialty Pharmaceutical Biotechnology Sales in Sarasota FL Resume Jeffrey MinettJeffreyMinettNo ratings yet

- Campus Advocates: United Nations Association of The USADocument10 pagesCampus Advocates: United Nations Association of The USAunausaNo ratings yet

- Ob MidtermDocument5 pagesOb MidtermSheila Tolentino-BelanioNo ratings yet

- REPORTDocument1 pageREPORTFoamy Cloth BlueNo ratings yet

- CIC-My Vision of CounsellingDocument4 pagesCIC-My Vision of CounsellingChristeeba F MNo ratings yet

- 12 Compulsive Activities ChecklistDocument8 pages12 Compulsive Activities ChecklistShrey BadrukaNo ratings yet

- Threats On Child Health and SurvivalDocument14 pagesThreats On Child Health and SurvivalVikas SamvadNo ratings yet

- Adolescent GangsDocument289 pagesAdolescent GangsReuben EscarlanNo ratings yet

- The Tactical Combat Casualty Care Casualty Card - TCCC Guidelines - Proposed Change 1301Document9 pagesThe Tactical Combat Casualty Care Casualty Card - TCCC Guidelines - Proposed Change 1301Paschalis DevranisNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)