Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dialogue, Culture, Critique: The Sociology of Culture and The New Sociological Imagination

Uploaded by

drpaviOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dialogue, Culture, Critique: The Sociology of Culture and The New Sociological Imagination

Uploaded by

drpaviCopyright:

Available Formats

Int J Polit Cult Soc (2005) 18:281292 DOI 10.

1007/s10767-006-9004-y

Dialogue, Culture, Critique: The Sociology of Culture and the New Sociological Imagination

Jeffrey C. Goldfarb

Published online: 22 November 2006 # Springer Science + Business Media, LLC 2006

Abstract In this paper, I show how the consideration of the role of the intellectual in democratic society informs an understanding of the critical project of the sociology of culture. This leads to a review of general sociological approaches to the problem of culture as they contribute to a critical project, suggesting the need for a distinctive conceptualization of the object of inquiry, culture as the arts and sciences, broadly understood. This approach requires making crucial distinctions, as well as studying key correlations. The distinctions are between: (1) Culture and Ideology, (2) High Culture and Autonomous Culture, and (3) Power and Knowledge. The correlations are between: (1) The Arts and Sciences, and Everyday Life, and (2) The Arts and Sciences, and Politics. At a time when the alternative to globalization is far from certain (this is what I get from the implicit debate between Calhoun and Beck), when the grounds for critique seem to be based on little more than nostalgic utopianism (this is how I understand Touraines prognosis of the end of society) or nostalgic pessimism (see Bauman) or hopeful pragmatism (Beck), I believe it is necessary to get closer to the pits of critical reflection and creative action in the cultural sphere. Casanova points to this in his consideration of religion in public life, even globalized religion (Casanova). Sassen (1998) suggests that we must understand globalization and its alternatives in their concrete local manifestations. Here, I would like to investigate secular alternatives, attempting to localize the critique of the global, showing how the traditions and projects of culture as the arts and sciences inform a collective intelligence with democratic deliberative dimensions (Pierre Levy). This is a call to keep alive critique in the postmodern circumstance, as part of an incomplete project of critical reflection and democratic action, a call for a sociology of culture as a key instrument for a renewed sociological imagination. The paper is centered on dialogue, (the relative autonomy of) culture, and critique. Keywords Dialogue . Culture . Critique

J. C. Goldfarb (*) Department of Sociology, New School for Social Research, 65 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10003, USA e-mail: goldfarj@newschool.edu

282

Int J Polit Cult Soc (2005) 18:281292

Dialogue It is around dialogue that I identify the distinctively democratic role of the intellectual (Goldfarb, 1998), and it is around dialogue that I identify the critical task of the sociology of culture. In our recent past, intellectuals from the left and the right were often in the anti-democratic vanguard. Twentieth century philosopher kings provided the ideologies that rationalized modern tyrannies. They, from Lenin to Hitler, from Heidegger to Sartre, invented and supported totalitarian orders. Yet, the opponents of modern tyranny included intellectuals also. The opponents of tyranny have been sometimes as tyrannical, or potentially so, as the tyrants they oppose. The anti-fascist alliances were often notably despotic, remember the experiences of Orwell in Spain, for example, and note that the controversies in Germany today around the uncomfortable recognition of Nazism as an extreme form of anti-communism. But sometimes tyranny can be opposed democratically. How do intellectuals do this? What is the distinctive role of democratic intellectuals? And what is the task of a more democratic cultural theory? My answer to these questions has to do with a most basic human activity: put variously as: discourse, conversation, dialogue, talk. When intellectuals provide, and directly enact, answers to the political problems of the day, when they impose their visions on an illinformed audience, they do not serve democracy. When they open opportunities for informed discussion about pressing problems, provoking conversation and deliberation among equals, their democratic responsibilities are accomplished. I suggest that there are basically two ways that they do this: civility and subversion. They civilize conflicts, enabling people with opposing interests and different points of view to converse with each other, facilitating mutual understanding and compromise, or at least recognition, and they subvert civilities that mask conflicts, which make the marginal and the dominated, and their problems, invisible. Civil intellectuals make it possible for foes to come to confront each other democratically. Subversive intellectuals reveal concealed problems. The discursive function of intellectuals is not merely a matter of personalities and individual talent and volition. It is socially constituted. It is grounded in social structure. This is where culture comes in. The cultural domain, with modernity, is a differentiated part of the greater social order of things. Weber (see Gerth & Mills, 1958) viewed this differentiation as the basis for alternative value commitments, apart from the rationality of the market and the authority of the state. The Frankfurt School, particularly Adorno (see Horkheimer & Adorno, 2002) and Marcuse (1991), saw it as a refuge from capitalist domination and its rationalities, an autonomous location where critique stays alive, where qualitative judgment persists in a sea of quantitative capitalist calculations. Nancy Hanrahan in her sociology of music, first developed as a dissertation at the New School, shows how the differentiation has a temporal dimension, taking on the criticisms of the autonomy of culture (Hanrahan, 2000). She highlights the contingency of cultural distinction not to bury it in the postmodern fashion, but in order to show how distinctions are maintained in and through time, how the temporal dimension opens up the opportunity for critique. (Thus, for her, music is the quintessential cultural form.) This same opportunity, in my view, supports democratic dialogue. But to embark on critically engaged empirical research, which supports critique and dialogue, the approach to culture has to be of a specific variety.

Approaching Culture Not all approaches to culture used by sociologists help us find the opportunity for critique and dialogue. Prevailing approaches lead us away from this. Broadly speaking, I can think

Int J Polit Cult Soc (2005) 18:281292

283

of two different kinds of approaches moving us away from critique, with many variations on the two themes: There is the grand approach to culture, which views it as the opposite of one or another set of variables. Thus, there are the arguments for a cultural sociology that Jeffrey Alexander presents. This is the approach to culture that in a sense starts with a philosophical anthropology: culture is the distinctively human capacity; culture is meaning, or belief, or symbolic system, or some combination of the three. As Alexander puts it culture is the order of meaningful action. (Alexander & Seidman, 1990, p. 2) Cultural sociology is understood as being in an active polemic with some other sociological approach or approaches, and it is said to be preferable because it gets to the heart of the matter of what it means to be human. (Read here culture versus Marxism or materialism). Less grandly, culture is seen to be just another variable, or set of variables, and some sociologists seem to want to follow the model of bringing the state back in. They would bring culture back into the sociology enterprise, especially comparative historical sociology. Eiko Ikegami is engaged in such a project (Ikegami, 1997), as is Mabel Berezin (Berezin, 1997), among others. In that the tasks of comparative historical sociology have been to account for the emergence of the modern state and the modern political economy, a.k.a., capitalism and its forces of production, with the cultural turn, the way cultural variables contribute to these long-term developments is studied. Both in the grand and not so grand approaches, culture presents an alternative to other sets of variables. Here there are legacies of the Marxist and anti-Marxist theoretical polemics and echoes of Alvin Gouldner s opening of American sociology in his critique of Talcott Parsons (Gouldner, 1990, following the critical path forged by Mills, 1959, in his Sociological Imagination). Gouldner reported in his Coming Crisis in Western Sociology that Talcott Parsons (1937) developed his social action theory in the 1930s to present an alternative to Marxism. Parsons, Gouldner argued, was trying to support the prevailing political and economic system, when capitalism really did seem to be on the brink of collapse. He wanted to explain how modern society stuck together (answering how social order is possible, the Hobbesian question, as Parsons put it). Differentiation and reintegration were his answers, with the important and central process of value generalization and adaptive upgrading. In other words, Parsons argued that in complex societies the differentiation of complexity could be handled through the development of a generalized system of common values, which towards the end of his career came to resemble, to a remarkable degree, the American version of the Protestant ethic, i.e. the work ethic. The crisis in capitalism was but a glitch in the process of value generalization and adaptive upgrading, a passing episode of what Durkheim called the abnormal division of labor. The task for cultural sociology, as Alexander has picked this up, is to develop a macroscopic analysis of societies focusing on the cultural answers to the Hobbesian question. How do values, beliefs and symbols work to explain social order? Further, beyond the conservativism of Parsons framework: how do they work to explain social change? In the less grand approach, the cultural variable is related to others, to account for the history of the state, economy or other social institutions. How much weight, then, do we give to culture versus material structure, to culture versus the workings of the state and the economy? There are two ways to proceed with this, it seems to me: either we in fact do understand culture as opposed to something else, and,

284

Int J Polit Cult Soc (2005) 18:281292

therefore, we take such questions seriously, understanding that the primary empirical project for cultural inquiry is the determination of its import in relationship with other variables or sets of variables. Or, we recognize that we are working with ways of interpreting, and we put the cultural and the non-cultural one on top of the other, next to each other if you prefer, and try to more fully understand the social world in the process. This, then, is not a competition between favored and disfavored explanations, to be empirically studied, rather it is an exercise in more thickly interpreting an infinitely complex human world, so that informed action becomes possible. Note the allusion to the methodological approach of Clifford Geertz (see Geertz, 1977) combined with a more practiced, directed, critical, orientation. I obviously prefer this approach. In that political and economic activity, the histories and structures of states and the markets, involve meaning, value and symbols, I dont understand how they can even analytically be separated from the cultural. A crucial example: Can we consider money as anything other than a symbolic representation and facilitator of exchange? It is one of the most cultural of objects, being nothing more than a symbol, which provides the possibility of exchange. When culture is considered in this fashion, the old questions of base and superstructure border on the meaningless. Thus, the most effective Marxist approaches to culture abandoned the polarity: including the approach of the Frankfurt School, which effectively argued that the final crisis in capitalism has been avoided with the development of culture as a fundamental base of the capitalist mode of production, i.e. the culture industry. And, thus, the work of cultural studies as initiated by Raymond Williams (see Higgens, 2001), who directly argued against the notion of base and superstructure, understanding that cultural understandings and products are basic to the production and reproduction of all social formations. Yet, there are activities that do seem to be distinctly cultural, or at least more cultural than other activities, and they have their own histories and relationships to other human activities and their histories. This brings us back to Weber, the Frankfurt School and Hanrahan. It points to another way to approach the problem of culture, one that seeks to define itself not as the opposite of something (the material order, the economy, the domain of power and the like), but in terms of its distinction. And, crucially, as Hanrahan highlights, the ways its distinctions are formed in social practices. This is where the argument for culture as the arts and sciences, broadly understood, comes in. It is where critique and dialogue become central to the enterprise of cultural theory.

Culture as the Arts and Sciences, Broadly Understood The notion that culture is a separate autonomous domain has gone in and out of fashion. It was initially the way to characterize modernity: as the scientific era, and as the era when the arts bloomed anew, developing some independence from religious and political authority. Social science, and particularly sociology, has questioned this approach. It has addressed modernity primarily in terms of its distinctive political and economic institutions, rather than in terms of creativity and scholarship. In a great deal of social science, in fact, the arts and sciences have often been indistinguishable from ideology. As Foucault (1970) has put it, thought has been explained through sensation. Missing is an understanding that along with modern political and economic institutions and practices, there have been distinctive cultural institutions and practices. A critical and dialogic cultural theory requires this understanding.

Int J Polit Cult Soc (2005) 18:281292

285

The arts and sciences have specific histories, which are no doubt shaped by the context of their creation and the interests of their creators. There is something to the famous quote by Marx, The ruling ideas of the time are the ideas of the ruling class. But there is also much that is missing. Ideas live beyond their times and have a way of reaching beyond the interests of their formation. Contrary to Marx, and critics of ideology more generally, ideas reach beyond the context of their creation, and even the specification of the context is not at all certain. The ideas of the arts and sciences are the special location for critique and dialogue in complex society. They do this in an odd, strikingly non-ideological way, succinctly summarized by Milan Kundera in his reflections on the novel, when he declares: The novelist needs to answer to no one but Cervantes (Kundera, 1988). The novelist is not someone who must be an economic or political agent of a particular kind. He or she can serve the powers or oppose them, be entrepreneurial or not, but the novelist, and artists and scholars more generally, must answer the questions raised by the creators of the forms that precede them; they must argue with them, emulate them, refine and simplify them. This is the social interactive, dialogic sociological dimension of cultural forms. To the degree that they persist through time and in space, despite economic and political pressures, despite the accidents of history and psychology, the distinctive existence of an independent culture, the autonomy and freedom of the arts and sciences, is sustained. We can identify specific forms because such freedom is sustained. It is only in the complete absence of freedom that ideology and culture become indistinguishable in the way that ideological critique and ideological cultural policy in their various guises would have it. I think of Soviet theater after the 1930s. Perhaps you might wish to think about some more recent creations of Hollywood. Western music exists because western musicians, and their audiences and critics, relate to the music and to each other with reference to its unfolding traditions. There may be pressures to make music adhere to a specific political project, think of the interactions between Prokofiev and Stalin, or there may be demands that music be commercially viable, consider what Nancy Hanrahan (2000) so graphically notes as the sound of money. But just because money has a sound and it influences music does not mean that there is no distinction to be made between the sound of money and music. Just because one can hear moneys sound does not mean that music no longer exists as a social activity different from other money making activities. Musics independence is then contingent, but realized in social interaction. The same holds for science and theater, poetry and philosophy. But what are we to make of the lost distinction between elite and popular culture? How are we to respond to the revelations about the ideological uses of cultural life? From Zhdanov and socialist realism to Philip Morris and contemporary art? Modern states, despotic and democratic, use the creativity of artists and scholars to lend to themselves a cultivated aura just as the princes of old once did. Corporations do the same. In the case of previously existing socialism, supportive fields of culture substituted for democratic legitimacy. Does this not suggest that the arts and sciences are but a part of the state ideological apparatus? Such questions point to the fact that making critical distinctions is as important as studying correlations in cultural inquiry. Consider three distinctions and two correlations.

Distinction #1: Culture and Ideology Sociologists often lose sight of fact that the distinction between culture and ideology is crucial for a viable cultural life. This is because the demonstration of the correlation

286

Int J Polit Cult Soc (2005) 18:281292

between cultural forms and the social context of their creation and reception is an important contribution that sociology makes to cultural studies. It is, in fact, the cornerstone of the sociology of knowledge. In his classic, Ideology and Utopia, Mannheim (1955) made sense of the chaotic politics and the ideological conflicts of Weimar Germany. He adopted the insights of Marx and his ideological critique but abandoned the valorization of the working class as the agent of truth in history. Liberal parties were understood as the parties of capital, conservative parties of real property, socialist parties of labor, but Mannheim went further. He showed that the conflicts between ideas were part of an overall structure of social and historical determination, leading to ideas that were both self consciously tendentious (in partial ideologies) and unconscious manifestations of positionality (in total ideologies). Yet, he maintained that an overall truth was still possible. The free floating intellectual as the sociologist of knowledge could determine the relationship between the partial truths, as manifestations of partisanship and positionality, and come to a synthetic understanding of the social and political conditions and truths of the times. Mannheims relationalism has been rejected. His attempt to confront the need to understand the social grounding of ideas, while avoiding the pitfalls of relativism has come to be understood, at best, as an interesting failure (see Ricoeur, 1986). Yet, the problem he confronted is still with us. The hope for knowledge beyond the limitations of context has been abandoned by many, while others steadfastly condemn sociological reductionism. The steadfast view the relativists as ideological, while the relativists view the steadfast in the same way. For the one, ignoring context obfuscates an important constituting part of cultural life. For the other, being overwhelmed by context does the same. On the one hand, it does matter that the history of philosophy has been written without the presence of women. On the other, that history is not summarized by that fact. Here is a central ground of the postmodern cultural wars. Distinctions are made for the purposes of engaging in academic conflict. For those who understand that context is the key to content, overlooking context clearly misleads. It is an ideology of the dominant. For those who appreciate that creative works reach beyond immediate context, the project of contextualizing is reductive. It reduces cultural endeavor to the conditions of its creation. It is an adversarial ideology. In both cases, ideology is confused with culture, even if in the first, this is a matter of principle, while in the second, it goes unrecognized. But if we understand culture, as the arts and sciences, broadly understood, the problem can be avoided. The project of maintaining cultural independence is challenged by political and economic forces. Sexism, racism, the power of capital, and the power of the state all shape cultural practices. This needs to be studied. But do they define cultural practices? This needs to be studied also. What are the social forces that lead to resistance to such definition? Such a question is central to a critical cultural sociology. It demonstrates how the distinction between ideology and culture is a matter of social practice to be investigated, not a matter of definition. This has been the topic of just about all my writing and research (see especially Goldfarb, 1983, 1989 and 1991).

Distinction #2: High Culture, Popular Culture and Autonomous Culture The distinction between ideology and culture applies to the central questions of critical theory. Much of the controversies regarding this intellectual tradition revolve around the issue of its elitism. High art and philosophy were said to be the effective ways of resisting the capitalist domination. On the face of it, this has been hard to take, especially for those

Int J Polit Cult Soc (2005) 18:281292

287

with democratic sensibilities. It even seemed as if Adorno (see Horkheimer & Adorno, 2002) and Marcuse (1991) were critical of those who responded to high culture with less refinement than they had. But missing in this sort of assessment of their position is an appreciation of the significance of their distinction between autonomous and high culture. They were not arguing for high culture as an ideology, but for autonomous culture as critical capacity. That Adorno was wrong about jazz is not central to his position. That there is a distinction to be made between the sound, vision and rationality of money, and music, art and philosophy, and that this distinction has critical importance are central. The critique of the culture industry is just as much focused on the canned entertainment of the philistine listener of classical music as it is a criticism of pop. This is not to say that the critical theorists were not victims of their own prejudices. Adorno on jazz is a case in point, but even more telling is that he and his colleagues did not consider the critical potential of a broader more potentially popular range of cultural forms, and they did not consider the critical creative potential of audience response. The contingency of cultural creativity is subject to the constraints and repressions of the polity and the economy in all sorts of cultural pursuits, something the critical theorists realized in their criticisms of classical culture, but the possibility for opposition to such constraints and repressions in all sorts of cultural pursuits also should be recognized. Then, even hip hop culture in New York or graffiti in Montreal may be understood as providing possibilities for an independent critical life. And we, as sociologists of culture, must weigh and judge how the demands of commerce and sensation interact with the attempts to create independent zones of critical reflection in unlikely as well as likely places, as has Josh Gamson (1999) in the case of talk television. My first research project was on the development of independent culture in Communist societies (see Goldfarb, 1979, 1983). I argued that cultural freedom was an important part of the life of previously existing socialism. I was not trying to explain away the very real and significant repressions of the party state. I was not minimizing the differences between the freedoms of a liberal polity with the unfreedoms of totalitarianism. I was emphasizing that despite repression an independent cultural life was sustainable in a repressive context. Independent theater, for this was my field of exploration, was developed despite censorship. The great works of national and international theater were confronted, elaborated upon, dismissed, criticized, developed, and a zone of independent cultural and, incidentally, political life was created. The people involved defined their situation by their actions and interactions. There was a struggle between those who repressed culture and those who created it. I studied cases where the latter group prevailed, despite the odds. The political consequences changed our world as well as theirs. The same holds true in the culture of the entertainment industry, even the mass entertainment industry. The people involved interact and interpret their interactions and act upon their interpretations. They engage in a struggle, and we must judge them. The distinction between mass culture, the culture of money for our purposes, and autonomous culture, is sustained by our subjects actions and our understanding of their actions. We are involved. The sound, vision, cognition of money predominates if people sustain them. For sound as music, vision as the visual arts, and cognition as philosophy to predominate requires making the distinction between the independent culture of the arts and sciences and their extra-cultural constraints. Power obviously is involved. Not all creators of culture are equal. Not all receivers of culture are. But (as my case of art in the old Soviet bloc suggests) that power is not only the power of the state or of money. The authority and persuasiveness of culture, as the arts and sciences (their creative potential), also present significant sources of power.

288

Int J Polit Cult Soc (2005) 18:281292

Distinction #3: Power and Knowledge Politics and culture have complicated relationships, and clearly cultural theory ought to take these relationships on. The most straightforward, if problematic, approach is the identification of knowledge with power, as Foucault (1970) has put it. The critical insight of this position is clear, although controversial for the sociologist. That culture is coercive, that ideology empowers, follows the basic insights of sociology of knowledge. The ideas about mental illness are a way to control situationally inappropriate social interaction. This is something that both Goffman (see for example, Goffman, 1959) and Foucault would agree upon. Yet, the conflation of force and reason is not a general condition of modernity, as Foucault implies, but a specific modern political form, that of modern tyranny, i.e., totalitarianism. Totalitarianism, as a distinctive cultural form, brings together ideology and terror. The two go hand and hand as Hannah Arendt (1973) demonstrated in her remarkable concluding chapter of The Origins of Totalitarianism. Ideology is understood in its specific historical meaning. Common to the ideologies that have prevailed in the modern era is a kind of magical mono-casual explanation of history and the human condition. The complexity of the social world is reduced to some underlying idea and deductions from that idea, archetypically, the ideas of race and class. All of the complexities of human existence are explained in terms of the simple ideas. They are intimately related to power, and the consequences have been tragic. Force defines reason and reason defines force. A set of relatively prosperous farmers are defined as class enemies, as kulaks, resisting the inevitable progress of the socialist revolution, and mass starvation results. The Jews, the European other, are defined as a degenerate race, the major obstacle to the thousand year Reich, and the Holocaust results. The theories predict the scientific inevitability of modern barbarism. The barbarism proves the theory. It is the height of academic foolishness to equate this situation with other instances of the relationship between power and culture. In liberal regimes, there is greater distance between power and culture. While it is true that the law does not fundamentally challenge the existing system of property relations, major economic powers can and have been challenged in the application of the law to the regulation of commerce (think Microsoft). Universities do serve the powers by disseminating ideas supportive of the status quo, but it is not a rare thing that critical ideas are an important part of academic life. Museums have exhibits that glorify the national traditions and nationalist conceptions of the order of things, but they also challenge nationalism. To be sure, sometimes the challenges are quieted. But the controversies that result, as documented in Vera Zolbergs (1998) and Steven Dubins (2000) recent work, clearly indicate the distance between power and culture. Such would not have been the case in Stalins Russia, even though in Soviet times the distance between the project of ideology and the complicated projects of modernity often created more room for a free cultural life than outsiders imagined. My work on the culture of the former Soviet bloc indicates that culture can be as much a form of resisting power as it is a form of disciplining power. This of course is an extreme instance of what Marcuse and Adorno long maintained.

Correlation #1: The Arts and Sciences and Everyday Life But what is the relationship between culture as the arts and sciences and broader more inclusive understandings of culture? When I maintained that the arts and sciences are a

Int J Polit Cult Soc (2005) 18:281292

289

particularly fruitful focus for the sociology of culture as a critical enterprise, I did not mean to suggest that other meanings of culture should be omitted from our inquiries, or are in any sense less important. Here it is important to consider how the arts and sciences approach would inform other approaches to cultural life. To begin with, thus, I add the broadly understood modifier. If we consider the arts as the full range of activities where artisanship is cultivated, where artifacts are made, and if we consider science in terms of the full range of activities where systematic reflection and observation are linked, we come to understand that the arts and sciences in fact do include a broad range of social activities. The specialized zones of the arts and sciences, where they develop with some independence from other significant spheres of social life, are linked to those other spheres first because in those spheres artistry and a sort of scientific inquiry are present. Identifying the link extends the critical enterprise. This is how we can approach the work of Erving Goffman (1959), for example (see Goldfarb, 2006). Goffmans dramaturgical approach to social life is, he confesses at the conclusion of The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, based on a metaphor. He analyzed everyday life as if it were theater. He wants to be clear that it is not theater itself. He uses theatrical terms to explain everyday interactionstage, role, performance and so forth. Yet, throughout the book and in much of his later work, he goes beyond metaphor and analyzes the theatrical elements of social interaction, as this is conventionally done by sociologists. Roles exist in society just as they exist in theater. The performance of roles are crafted and developed, and even self-consciously taught. As Simmel (1973) pointed out in his brilliant path-breaking analysis of the sociology of theater, the particular function of an art becomes an art when it becomes an end in itself. The acting of everyday life and the acting in theater cannot be distinguished outside of their particular performative projects. It becomes interesting, then, to consider how the performances of daily life, the visual artistry, the cognitive theories, the music, etc. are related to the institutionally specialized cultural endeavors of the arts and sciences, and how the most distanced cultural pursuits are related to the most embedded, by intermediary practices, by movements in the arts and sciences of various sorts. This is where Robin Wagner Pacificis (e.g., see Wagner Pacifici, 2000) analysis of stand-offs, considering the tragic interaction between the language arts of government bureaucracy, the police and of social movements, comes to mind. And it is where Eviatar Zerubavels (e.g., see Zerubavel, 1993) consideration of cognitive sociology presents itself as being of central importance. When he is considering distinctions, mapping, the ordering of the week, Zerubavel passes freely from the more to less embedded scientific practices, and he considers how they effect each other. When she considers stand-offs of Wounded Knee, Move and in the Aldo Moro affair, Pacifici considers how the arts and sciences of institutions and movements confront each other with mutual misunderstanding. There is the history of the historians and collective memories of institutions and social movements, how they interact shapes the identity of nations, especially as they consider their legendary figures such as Washington and Lincoln, as Barry Schwartz (1990, 2003) has demonstrated. I think it should be clear that there is no necessary connection between the arts and sciences of daily life, and the institutionalized arts and sciences, and the arts and sciences of social movements. The connections vary and should be documented. They vary because of the projects of social actors and the influences of social structures. But one thing should be clear, it is not a matter of reflection, of culture in any of its meanings reflecting something more fundamental, some more determinative factor. Once I delivered a paper at an annual American Sociological Association meeting that I have a special fondness for, Bringing Culture Back in, by keeping it out, This paper is a

290

Int J Polit Cult Soc (2005) 18:281292

kind of update of that. I changed my polemical mind on a number of issues, but on one I remain firm. I declared that when I hear the word reflection applied in the sociology of culture, I reach for my red pen, if not my gun. There is no identity between and among the arts and sciences, no necessary correlation with some more real reality. There is variation to be studied, correlations to be explored. There are different cultural activities with developing contingent histories, their autonomies and interrelationships. These are foci of empirical investigations in the sociology of culture.

Correlation #2: The Arts and Sciences and Politics And the study of the correlations and the autonomies has moral and political implications. There are consequences in the choice of correlations and autonomies we study and in the way we study them. Political and ethical commitments precede and follow from our studies. What is the role of the intellectual in democratic society? The question suggests a consideration of the relationship between types of actions of intellectuals and their correlation with types of politics. The choice of the subject matter of the study was politically and ethically motivated, as are its potential consequences. I was struck by a paradox: intellectuals have been among the chief agents and opponents of modern tyranny. They have mattered in our recent past, while in the present there seems to be a consensus that they no longer matter. Yet, a major problem we face in our democratic life is exactly what democratic intellectuals facilitate in tyrannical contexts. They facilitate democratic discussion, by civilizing differences and subverting civilities that hide social problems. They address what I have called the deliberation deficit. For me, political commitments and scholarship are intimately connected, each informing the other. Yet, it seems to me also that there are distinctions that need to be made between the roles of scholar, intellectual, citizen and politician. The kinds of distinctions that Weber analyzed in his vocational essays, Science as a Vocation and Politics as a Vocation (see in Gerth & Mills, 1958). The public opening that culture (as the arts and sciences broadly understood) provides, cannot be defined by a political imperative, or an economic one. It can be influenced by political and economic factors, but it must develop on its own terms to some significant degree. Discerning to what degree is a matter of professional judgment and commitment. Otherwise our sociology of culture could develop a sound of money or of partisan politics. And it often does. Funding agencies define theoretical developments. Unexamined political prejudices substitute for systematic theoretical critical reflection, whether they are the prejudices of a Parsons or the prejudices of a Gouldner or of a Mills. We must be careful to avoid the substitution of ideology for the commitment to critique and ethical reflection. This is where I think the dialogic project becomes crucial. I am very much the student of my mentor, Donald Levine. In his masterwork Visions of the Sociological Tradition (Levine, 1995), he reconstructs the history of sociology as a number of distinct alternative narratives and calls for the fruitful dialogue among them as a way of realizing sociologys promise. He closes his text with a call for dialogue as an answer for disciplinary and public fragmentation. In this paper, I am presenting a variation on his theme, actually an expansion. Sociology is a case in point of a cultural form as an art and science. Its theoretical development depends upon the conversation we have with our predecessors and contemporaries about the issues of sociological concern, keeping the sociological imagination alive. The disciplinary autonomy and dialogue make it so that we can engage in our studies informed by and informing our political commitments, and social identities, even as we understand that they are not definitive of the discipline. Novelists

Int J Polit Cult Soc (2005) 18:281292

291

must answer only Cervantes, as we must answer, Marx, Weber, Simmel and Durkheim, and Talcott Parsons and C. Wright Mills and Alvin Gouldner. This does not mean that political concerns dont motivate a Milan Kundera, or sociologists such as ourselves, making his and our work more significant. It actually makes it possible for these concerns to be addressed, distinguishing politics from culture, and both from ideology. I am taken by Ulrich Becks attempt to ground a new cosmopolitan alternative to globalization, as it appears in this volume. It seems to me that his sober account of global forces is nicely informed by sophisticated studies of the phenomena such as Sassens (1998). But there was something unreal or altogether too real about his proposal of the cosmopolitan alternative. On the one hand, in general, the basis in social action of the cosmopolitanism seemed unclear, while, in particular, it seemed to be ultimately too concretely grounded in the practical action of creating a political culture for the European Union. My proposal here is that a critical sociology of culture, as the arts and sciences, broadly understood, points to the practical sphere of creative critical activity where the much needed cosmopolitanism is grounded.

References

Alexander, J. C., & Seidman, S. (1990). Culture and society: Contemporary debates. New York: Cambridge University Press. Arendt, H. (1973). The origins of totalitarianism. San Diego: Harvest. Berezin, M. (1997). Making the Fascist self: The political culture of interwar Italy. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. Dubin, S. (2000). Displays of power: Controversy in the American Museum from enola gay to sensation. New York: New York University Press. Foucault, M. (1970). The order of things: An archaeology of the human sciences. New York: Random House. Gamson, J. (1999). Freaks talk back: Tabloid talk shows and sexual nonconformity. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Geertz, C. (1977). Interpretation of cultures. New York: Basic Books. Gerth, H., & Mills, C. W. (1958). From Max Weber. New York: Oxford University Press. Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of life in everyday life. New York: Knopf. Goldfarb, J. C. (1979). The persistence of freedom: The sociological implications of Polish student theater. Boulder: Westview. Goldfarb, J. C. (1983). On cultural freedom: An exploration of public life in Poland and America. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Goldfarb, J. C. (1989). Beyond glasnost: The post totalitarian mind. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Goldfarb, J. C. (1991). The cynical society: The culture of politics and the politics of culture in American life. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Goldfarb, J. C. (1998). Civility and subversion: The intellectual in democratic society. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Goldfarb, J. C. (2006). The politics of small things: The power of the powerless in dark times. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Gouldner, A. (1990). The coming crisis of western sociology. New York: Basic Books. Hanrahan, N. W. (2000). Difference in time: A critical theory of culture. Westport, CT: Greenwood. Higgens, J. (ed.) (2001). The Raymond Williams reader. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. Horkheimer, M., & Adorno, T. (2002). The dialectics of enlightenment. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Ikegami, E. (1997). The taming of the Samurai: Honorific individual and the making of modern Japan. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Kundera, M. (1988). The art of the novel. New York: Grove. Levine, D. (1995). Visions of the sociological tradition. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Mannheim, K. (1955). Ideology and Utopia: An introduction to the sociology of knowledge. Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. Marcuse, H. (1991). The aesthetic dimension: Toward a critique of Marxist aesthetics, (2nd ed.). Boston: Beacon. Mills, C. W. (1959). The sociological imagination Oxford University Press. New York: Oxford University Press.

292

Int J Polit Cult Soc (2005) 18:281292

Parsons, T. (1937). The structure of social action, vol. I and II. New York: McGraw-Hill. Ricoeur, P. (1986). In G. H. Taylor (Ed.), Lectures on ideology and Utopia. New York: Columbia University Press. Sassen, S. (1998). Globalization and its discontents: Essays on the new mobility of people and money. New York: New Press. Schwartz, B. (1990). George Washington: The making of an American symbol. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. Schwartz, B. (2003). Abraham Lincoln and the forge of national memory. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Simmel, G. (1973). On the theory of theatrical performance. In E. Burns, & T. Burns (Ed.), Sociology of literature and drama. Baltimore: Penguin. Wagner Pacifici, R. (2000). Theorizing the Standoff: Contingency in action. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Zerubavel, E. (1993). The fine line. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Zolberg, V. (1998). Contested remembrance: The Hiroshima exhibit controversy. In Theory and society, vol. 27, no. 4 (pp. 565590) (August).

You might also like

- Art and The $ensesDocument679 pagesArt and The $ensesDiego A Falconi A60% (5)

- Popular Culture: From John Storey's Popular Cuture and Cultural TheoryDocument29 pagesPopular Culture: From John Storey's Popular Cuture and Cultural TheoryUsha RajaramNo ratings yet

- Practical Research 1 11 09 19 PDFDocument310 pagesPractical Research 1 11 09 19 PDFArjey B. Mangakoy100% (2)

- Introduction To Cultural Studies For PkbuDocument16 pagesIntroduction To Cultural Studies For PkbuTalayeh Ghofrani100% (1)

- Popular Culture An Onto Historical Approach Autosaved 1Document25 pagesPopular Culture An Onto Historical Approach Autosaved 1garcianocleo20No ratings yet

- Intellectuals New Public SpheresDocument15 pagesIntellectuals New Public SpheresKarissa Rae McKelveyNo ratings yet

- Democracy's Children: Intellectuals and the Rise of Cultural PoliticsFrom EverandDemocracy's Children: Intellectuals and the Rise of Cultural PoliticsRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Chapter On PostmodernismDocument11 pagesChapter On PostmodernismAti SharmaNo ratings yet

- Sociologiy Essay On Approaches To The Study of Popular CultureDocument6 pagesSociologiy Essay On Approaches To The Study of Popular CultureArnold Waswa-IgaNo ratings yet

- Popular CultureDocument3 pagesPopular CultureRussel YamitNo ratings yet

- Mathieu Deflem - Lady Gaga and The Sociology of Fame - The Rise of A Pop Star in An Age of Celebrity (2017) (022-058)Document37 pagesMathieu Deflem - Lady Gaga and The Sociology of Fame - The Rise of A Pop Star in An Age of Celebrity (2017) (022-058)Milena BaroneNo ratings yet

- Postmdernism Theory: Abdulazim Ali N.Elaati 25-5-2016Document7 pagesPostmdernism Theory: Abdulazim Ali N.Elaati 25-5-2016NUSANo ratings yet

- Resumen Linda HutcheonDocument3 pagesResumen Linda HutcheonMalena BerardiNo ratings yet

- ZfE 133-2 257-282 DemmerDocument26 pagesZfE 133-2 257-282 Demmerulrich_demmerNo ratings yet

- Ferguson, Stephen C. 2007 'Social Contract As Bourgeois Ideology' Cultural Logic (19 PP.)Document19 pagesFerguson, Stephen C. 2007 'Social Contract As Bourgeois Ideology' Cultural Logic (19 PP.)voxpop88No ratings yet

- Res Glut I 0 N: & NFL I C TDocument10 pagesRes Glut I 0 N: & NFL I C TJason ChenNo ratings yet

- Cultural Diamond in 3DDocument43 pagesCultural Diamond in 3DArely MedinaNo ratings yet

- Between Community and The Other: Notes of Cultural AnthropologyDocument6 pagesBetween Community and The Other: Notes of Cultural AnthropologyMichele Filippo FontefrancescoNo ratings yet

- From Postmodernism To PostcolonialismDocument13 pagesFrom Postmodernism To PostcolonialismkawaiiNo ratings yet

- PostmodernismDocument31 pagesPostmodernismManal SaidNo ratings yet

- 1 - 1 Rege 2000Document18 pages1 - 1 Rege 2000Kushal TekwaniNo ratings yet

- Music in MovementsDocument17 pagesMusic in MovementsChibi_MeztliNo ratings yet

- Modernity OxfordDocument24 pagesModernity OxfordtamiratNo ratings yet

- Chapter IiDocument12 pagesChapter IiElixer ReolalasNo ratings yet

- Definitions and Expressions of "Postmodernism": by Maria I. MartinezDocument3 pagesDefinitions and Expressions of "Postmodernism": by Maria I. MartinezNoel J HaNo ratings yet

- 'Cosmopolitanism': January 2011Document8 pages'Cosmopolitanism': January 2011danielrubarajNo ratings yet

- Different Modalities of Modernity: Imagined, Alternative, Global, EtcDocument15 pagesDifferent Modalities of Modernity: Imagined, Alternative, Global, EtcMerve KaracaogluNo ratings yet

- Modernity at LargeDocument3 pagesModernity at LargeHelenasousamNo ratings yet

- POSTMODERNISMDocument31 pagesPOSTMODERNISMmuhammad haris100% (3)

- Contemp. Culture - CURSDocument33 pagesContemp. Culture - CURSfifiNo ratings yet

- SM 1cultureDocument128 pagesSM 1cultureshivam mishraNo ratings yet

- Traditions of The Post SummaryDocument3 pagesTraditions of The Post Summaryjaunty kalaNo ratings yet

- Charles Macdonald - The Anthropology of AnarchyDocument25 pagesCharles Macdonald - The Anthropology of AnarchycrispasionNo ratings yet

- From Culturalism To TransculturalismDocument19 pagesFrom Culturalism To TransculturalismCristina SavaNo ratings yet

- Mafeje Varios Textos PDFDocument57 pagesMafeje Varios Textos PDFNatália AdrieleNo ratings yet

- Postmodernism: The Hibbert JournalDocument9 pagesPostmodernism: The Hibbert JournalGerald DicenNo ratings yet

- Cultural MaterialismDocument7 pagesCultural MaterialismDavid Lalnunthara DarlongNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 - Theories in Pop CultureDocument9 pagesChapter 2 - Theories in Pop CultureGreen GeekNo ratings yet

- Literature and Cultural StudiesDocument20 pagesLiterature and Cultural Studiesvanilla_42kp100% (1)

- Chapter 2Document4 pagesChapter 2Vianne SaclausaNo ratings yet

- The Observation of Participation and The Emergence of Public EthnographyDocument22 pagesThe Observation of Participation and The Emergence of Public EthnographyjelenaveljicNo ratings yet

- Cont Mod 1Document27 pagesCont Mod 1Ulrich DemmerNo ratings yet

- Kisi Materi Decontruction of Culture in MediaDocument9 pagesKisi Materi Decontruction of Culture in MediaAbi Hasbi RamadhanNo ratings yet

- Lecture 6Document4 pagesLecture 6Нурмухамед КубегенNo ratings yet

- Akash Shinde (A) - PostmodernismDocument21 pagesAkash Shinde (A) - PostmodernismNIKHIL CHAUDHARINo ratings yet

- What Is Popular Culture? A Discovery Through Contemporary ArtDocument41 pagesWhat Is Popular Culture? A Discovery Through Contemporary ArtleiNo ratings yet

- Postmodern EthnographyDocument28 pagesPostmodern Ethnographyrasroger100% (1)

- History and Theory 41 (October 2002), 301-325 © Wesleyan University 2002 ISSN: 0018-2656Document25 pagesHistory and Theory 41 (October 2002), 301-325 © Wesleyan University 2002 ISSN: 0018-2656Bogdan-Alexandru JiteaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Cultural SociologyDocument3 pagesIntroduction To Cultural SociologyOndra KlímaNo ratings yet

- Culture HandoutDocument4 pagesCulture HandoutGian Angela SancejaNo ratings yet

- Bhabha - Homi Boundaries Differences PassagesDocument16 pagesBhabha - Homi Boundaries Differences PassagesJingting Felisa ZhangNo ratings yet

- Cross Cultural 4Document50 pagesCross Cultural 4eecekaratasNo ratings yet

- Statistically MotivatedDocument3 pagesStatistically MotivatedShay WaxenNo ratings yet

- Writing Critical Ethnography DialogueDocument15 pagesWriting Critical Ethnography DialogueKaterina SergidouNo ratings yet

- Ucult ReviewerDocument11 pagesUcult ReviewerApril Hilarylynn Lawa JagunosNo ratings yet

- My Thoughts On Culture and ClassDocument10 pagesMy Thoughts On Culture and ClassScott ForsterNo ratings yet

- Langlois - BSG ReviewDocument96 pagesLanglois - BSG ReviewNicholas KierseyNo ratings yet

- Ehtnographies Neoliberalism Ch4 JPDocument322 pagesEhtnographies Neoliberalism Ch4 JPlola.carvallhoNo ratings yet

- Benhabib 94 Metapoltics Derrida LyotardDocument24 pagesBenhabib 94 Metapoltics Derrida LyotardThorn KrayNo ratings yet

- Making Sense of Our Everyday ExperiencesDocument26 pagesMaking Sense of Our Everyday ExperiencesMary Joy Dailo100% (1)

- Week 1 Sociology IntroDocument20 pagesWeek 1 Sociology Intronayf.albadanyNo ratings yet

- TNEA Notification Is OutDocument1 pageTNEA Notification Is OutdrpaviNo ratings yet

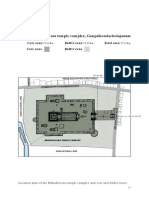

- The Brihadisvara Temple Complex, GangaikondacholapuramDocument1 pageThe Brihadisvara Temple Complex, GangaikondacholapuramdrpaviNo ratings yet

- The Airavatesvara Temple Complex, DarasuramDocument1 pageThe Airavatesvara Temple Complex, DarasuramdrpaviNo ratings yet

- Counselling Schedule For Mbbs Admissions 2010-2011: Selection Committee Directorate of Medical Education, Chennai - 10Document1 pageCounselling Schedule For Mbbs Admissions 2010-2011: Selection Committee Directorate of Medical Education, Chennai - 10drpaviNo ratings yet

- CANNONBALL TREE Is A Deciduous Tree. Native To Tropical South America (ParticularlyDocument1 pageCANNONBALL TREE Is A Deciduous Tree. Native To Tropical South America (ParticularlydrpaviNo ratings yet

- MY Bio Data Name R.Kaviya Father Name R. Ravicha Ndran Mother Name R.Vennila Sister Name R.Atchaya My Aim DoctorDocument1 pageMY Bio Data Name R.Kaviya Father Name R. Ravicha Ndran Mother Name R.Vennila Sister Name R.Atchaya My Aim DoctordrpaviNo ratings yet

- Epigastric Hernia Repair: Error! Bookmark Not DefinedDocument6 pagesEpigastric Hernia Repair: Error! Bookmark Not DefineddrpaviNo ratings yet

- Dengue FeverDocument12 pagesDengue FeverdrpaviNo ratings yet

- MD General Medicine Part - II ExaminationDocument19 pagesMD General Medicine Part - II ExaminationdrpaviNo ratings yet

- Platoon Records Main Cash Book Duty Roaster Parade RegisterDocument4 pagesPlatoon Records Main Cash Book Duty Roaster Parade RegisterdrpaviNo ratings yet

- BronchiectasisDocument6 pagesBronchiectasisdrpaviNo ratings yet

- LP For CTUDocument2 pagesLP For CTUGogo R. JugieNo ratings yet

- Pre-Observation Form 2018-2019Document2 pagesPre-Observation Form 2018-2019api-458245563100% (1)

- Pattern Recognition: Talal A. Alsubaie SfdaDocument40 pagesPattern Recognition: Talal A. Alsubaie SfdasakthikothandapaniNo ratings yet

- Social IntelligenceDocument2 pagesSocial IntelligenceRadhika DhanakNo ratings yet

- The Retrospective View of Ford'S Field Recall Coordinator Ford'S Pinto FiresDocument1 pageThe Retrospective View of Ford'S Field Recall Coordinator Ford'S Pinto FiresNURULNo ratings yet

- John Plass - Buddhist Meditation and The Science of Subjectivity (Single Spaced)Document114 pagesJohn Plass - Buddhist Meditation and The Science of Subjectivity (Single Spaced)John C Plass100% (1)

- IMC18713Document8 pagesIMC18713Alok NayakNo ratings yet

- 03 Third Class of Seminar 2012 Part 1Document4 pages03 Third Class of Seminar 2012 Part 1Terence BlakeNo ratings yet

- Stereotype LessonDocument4 pagesStereotype Lessonapi-282475000No ratings yet

- Key Terms in PragmaticsDocument260 pagesKey Terms in PragmaticsNunu Ab Halim100% (2)

- The Reconciliation Between Rationalism and EmpiricismDocument2 pagesThe Reconciliation Between Rationalism and EmpiricismSahidur IslamNo ratings yet

- Bloom's Taxonomy Guide (COLOR) - 2015-CIDDEDocument1 pageBloom's Taxonomy Guide (COLOR) - 2015-CIDDEJhonabie Suligan CadeliñaNo ratings yet

- Assure ModelDocument2 pagesAssure Modelapi-317151826No ratings yet

- Socratic Wisdom and The Search For DefinitionDocument5 pagesSocratic Wisdom and The Search For DefinitionPangetNo ratings yet

- Being Judgemental and CriticalDocument2 pagesBeing Judgemental and CriticalmalsrinivasanNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Teaching English Subject Using Drama On The Development of Critical Thinking PDFDocument10 pagesEffectiveness of Teaching English Subject Using Drama On The Development of Critical Thinking PDFZulaikha ZulkifliNo ratings yet

- Improving Teaching Vocabulary Through Real Object MethodDocument9 pagesImproving Teaching Vocabulary Through Real Object MethodIdris SardiNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Framework Equity TheoryDocument3 pagesTheoretical Framework Equity TheoryGuste Sulit RizaNo ratings yet

- 321 EssayDocument3 pages321 EssayCarlos GuiterizNo ratings yet

- Module 1 - Doing PhilosophyDocument52 pagesModule 1 - Doing PhilosophyJoyce AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- 2689498Document14 pages2689498limuvi100% (1)

- Ela 11 Unit 3 Elements of PersuasionDocument39 pagesEla 11 Unit 3 Elements of Persuasionapi-327147831No ratings yet

- GreerSingerDudekobs PDFDocument15 pagesGreerSingerDudekobs PDFAshagre MekuriaNo ratings yet

- Freedom ResponsibilityDocument8 pagesFreedom ResponsibilityGuilherme CavatortaNo ratings yet

- Rubric For Build A ChairDocument2 pagesRubric For Build A ChairStratos VasiliadisNo ratings yet

- Teaaching Writing Differentiated Instruction With Level Graphic OrganizersDocument96 pagesTeaaching Writing Differentiated Instruction With Level Graphic Organizersanjeleta89% (19)

- My Unit Daily Lesson Plan Cloze ReadingDocument3 pagesMy Unit Daily Lesson Plan Cloze Readingapi-235251591No ratings yet