Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Florian Bieber, Reconceptualizing The Study of Power-Sharing

Uploaded by

Florian BieberOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Florian Bieber, Reconceptualizing The Study of Power-Sharing

Uploaded by

Florian BieberCopyright:

Available Formats

ReconceptualizingtheStudyofPowerSharing

ReconceptualizingtheStudyofPowerSharing

byFlorianBieber

Source: SoutheastEurope.JournalofPoliticsandSociety(Sdosteuropa.ZeitschriftfrPolitikund Gesellschaft),issue:04/2012,pages:526535,onwww.ceeol.com.

Sdosteuropa 60 (2012), H.4, S. 526-535

RESEARCH ON STATE-BUILDING

FLORIAN BIEBER

Reconceptualizing the Study of Power-Sharing

Abstract. This article argues for re-conceptualizing the study of power-sharing in post-conflict state-building. In Southeastern Europe, as elsewhere, power-sharing has become the most widely employed approach to accommodate the competing demands of ethnonational groups. As aresult, the Southeastern European cases of power-sharing have been important for the larger study of power-sharing and post-conflict state-building. This article argues that in order to draw meaningful conclusions from these cases, the study of power-sharing needs to become more multi-dimensional, moving away from the study of formal institutional rules to include historical context, local debates, the strength of the state and the performance of the formal procedures to derive amore meaningful picture of power-sharing. Such reconceptualization will not just enhance our understanding of power-sharing in Southeastern Europe, but contribute more broadly to amore nuanced debate on this subject. Florian Bieber is Professor for Southeast European Studies and Director of the Centre for Southeast European Studies at the University of Graz.

Since the collapse of Yugoslavia and the ensuing wars, over adozen new states and para-states have been built and wiped out on the territory of the socialist federation. Today, there are seven post-Yugoslav states, comprising all the former republics plus Kosovo. The states that were proclaimed, and which were based on ethno-territorial lines but did not follow the republican boundaries of Yugoslavia, remain phantom states, like the Ilirida in Western Macedonia, or suffered military defeat, such as the Republika Srpska Krajina in Croatia. At best, they could establish themselves as an autonomous region or entity such as the Republika Srpska within Bosnia and Herzegovina. The new states were established either as (aspiring) nation states with varying degrees of the exclusion of others or as multinational power-sharing systems. The latter was not the result of domestic negotiations, but rather of external imposition. In effect, the default model of external state-building has been power-sharing. Not only states that came into existence, but also numerous unimplemented plans, such as the Carrington Plan for Yugoslavia in 1991 or the Z4 Plan for Croatia in 1995 or temporary political settlements such as the short-lived State Union of Serbia and Montenegro (2003-2006), contained

Access via CEEOL NL Germany

Reconceptualizing the Study of Power-Sharing

527

strong power-sharing features, such as veto rights, autonomy and proportional representation. Today three political regimes in Southeastern Europe display features of power-sharing, namely Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, and Macedonia. These have been shaping academic debates on consociationalism for the past decade well beyond Southeastern Europe. Among proponents of power-sharing, these cases, in conjunction with other examples of post-conflict power-sharing, have advanced the inclusion of third parties, as an integral aspect in the establishment and maintenance of power-sharing systems. Thus, international organizations in particular have taken on asupervisory function and have been institutionally embedded into the system, through, for example, the inclusion of international judges in the Constitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The power-sharing systems, drafted largely by external planners, have been labelled complex power-sharing because the institutional tools employed extend beyond the narrow understanding of consociationalism as defined by Arend Lijphart in his studies on West European Consociational systems. Complex power-sharing also incorporate forms of territorial autonomy and centripetal tools.1 Critics of power-sharing have, on the other hand, taken the performance of power-sharing systems in Southeastern Europe as evidence of the inappropriateness of power-sharing and its role as part of the problem by facilitating state capture and the ethnification of society and the political system.2 In response to the obvious flaws of rigid power-sharing systems, such as the one in Bosnia and Herzegovina, advocates of consociationalism have begun distinguishing between liberal and corporate consociations to allow differentiation between systems which are rigid and reify ethnicity and those which can co-exist with liberal democracy.3 In the context of the experience of power-sharing in Southeastern Europe, I will argue that some aspects have been neglected in the larger scholarly debates that merit our attention. Rather than just seeing the cases as evidence for or against power-sharing, which is not avery fruitful venue of inquiry, the cases need first to be properly understood. Rather than just noting that context

1Stefan Wolff, Complex Power-Sharing and the Centrality of Territorial Self-Governance in Contemporary Conflict Settlements, Ethnopolitics, 8 (2009), n.1, 27-45, 29. 2Donald Rothchild/Philip Roeder, Dilemma of State-Building in Divided Societies, in: ibidem (eds.), Sustainable Peace. Power and Democracy after Civil War. Ithaca/NY, London 2005, 1-26, 5; Anna K. Jarstad, Power-Sharing: Former Enemies in Joint Government, in: Anna K. Jarstad/Timothy D. Sisk (eds.), From War to Democracy. Dilemmas of Peacebuilding. Cambridge 2008, 105-134. 3Brendan OLeary, Debating Consociational Politics: Normative and Explanatory Arguments, in: Sid Noel (ed.), From Power-Sharing to Democracy: Post-Conflict Institutions in Ethnically Divided Societies. Montreal, Kingston 2005, 3-43.

528

Florian Bieber

matters or that one needs to know more, this article argues that there are five strands of knowledge when it comes to power-sharing that have been neglected and need to be brought back into the study of power-sharing and institutional design in order to assess these institutional solutions and derive informed case studies for larger scale comparisons.

Historical Context

Recent literature on institutional design has been largely devoid of historical context. This is the result of the evolution of the debate on consociationalism, which originally focused extensively on historical context. They sought to explain the origins of power-sharing institutions through an elite bargain and were interested in the broader social traditions of compromise and accommodation. This focus has been abandoned due to a shift in the debate from consociationalism as an empirical description of the political system of aset of countries (commonly Benelux, Austria and Switzerland) towards aprescriptive approach.4 I believe that historical experience with different forms of compromise and accommodation in former Yugoslavia is necessary for our understanding of contemporary institutions, highlighting the need to bring the past into the analysis of power-sharing. Yugoslavia itself had strong power-sharing features, as did some of its republics, especially Bosnia and Herzegovina and to some degree Croatia. During the first decades of socialist rule, the institutions of power-sharing were not necessarily matched by power-sharing practices, as the ruling elites of the republics were not motivated by ethnicity or even primary republican loyalty, but sought the devolution of the system as atool to secure legitimacy. However, by the 1970s and especially after Titos death, the system had gravitated towards power-sharing with strong effective veto rights of the republics and aweak centre, with republican interests becoming amore prominent feature of the system. Thus, the post-war institutions in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo and Macedonia may have been drawn up by international mediators, but the institutions they set up often resemble the Yugoslav ones, and institutional practices, such as the state presidency in Bosnia and Herzegovina, have to be seen not just in terms of ruptures, but also in terms of continuities. As Donald Horowitz noted in 1993:

4The importance of historical context has been part of the debate of consociationalism, see Arend Lijphart, The Evolution of Consociational Theory and Consociational Practices, 1965-2000, Acta Politica (2002), special issue, n.1/2, 11-22, 14.

Reconceptualizing the Study of Power-Sharing

529

One of the ironies of democratic development is that, as the future is being planned, the past intrudes with increasing severity. In this field, there is no such thing as afresh start.5

The impact of past experience is hard to quantify, which is one of the reasons that the past has often been ignored in the literature on power-sharing. The lack of experience of cooperation and of power-sharing institutions is often said to be an obstacle for setting up power-sharing systems. In this sense, the post-Yugoslav cases of power-sharing would be expected to do better than elsewhere. However, this experience is not always an obvious asset. The failure of Yugoslavia and its break-up have also been asource of scepticism towards power-sharing and federalism. Rather than reducing the past to abeneficial or negative factor with regards to power-sharing, it needs to be considered in its complexity.

State Strength

Power-Sharing as part of apost-conflict state-building strategy also needs to be understood in the context of state capacity, state contestation and state strength. Without these dimensions, there is arisk that power-sharing is decontextualized from other features of the state. In his work on state-building, Francis Fukuyama argued that states should be considered in terms of both their strength, i.e. the ability to enforce policies and the scope of their functions, i.e. the ambition of the state in terms of the fields in which it engages (i.e. social services, health care).6 It matters profoundly whether the state that is governed through powersharing is astate with large enough scope and sufficient strength, i.e. whose impact is widely felt and with the capacity to take decisions in alarge number of policy areas. or whether the state is astate with few competences and possibly alimited reach and where, in effect, little power is shared. Here the cases from Southeastern Europe raise interesting questions. At first glance, astate with limited scope would seem to have greater chances of faring well as apower-sharing system, as there are fewer points of contestation and thus fewer opportunities for blockage in the decision making process. An example for such aweak state in terms of scope (and strength) would be Lebanon, which has privatized many state functions. In Southeastern Europe, Bosnia and Herzegovina and the short-lived State Union of Serbia and Montenegro are examples of weak states governed by power-sharing. The dissolution of the latter and the perpetual crisis of the former suggest that the combination of

5Donald L. Horowitz, The Challenge of Ethnic Conflict. Democracy in Divided Societies, Journal of Democracy 4 (1993), n.4, 18-37, 23. 6Francis Fukuyama, The Imperative of State-Building, Journal of Democracy 15 (2004), n.2, 17-31, 21f.

530

Florian Bieber

aminimal state and power-sharing does not necessarily lead to stable political arrangement. In fact, both cases lack both scope that is sufficiently broad with the capacity to enforce an already severely limited leverage. This is for two reasons. First, most citizens in Southeastern Europe expect astate to have abroad scope, based on the socialist experience. Alimited scope reduces the ability of citizens to identify with the state and empowers alternative sub-state structures that provide health care, social services, housing, etc. For example, a2007 UNDP-commissioned study in Bosnia and Herzegovina found strong support for wider involvement by the institutions of the state. Among citizens who cite adecent standard of living as the greatest priority, 96.5% consider the state responsible for providing it.7 Second, EU enlargement in Southeastern Europe interjects aparticular dynamic where states are required to have ahigh level of strength (even if not necessarily scope) to implement policies and laws and enforce rules. Thus, despite a variety of political systems that can be found among EU member states (from centralized unitary states to federal systems), they share at least the requirement of state strength.8 Rather than conclusively answering the question about the interrelationship between state capacity and ambition and power-sharing, these points should highlight that there is agreat variety of states in terms of their ability to enforce rules and their ambition as to which spheres they govern. The states that emerge from such adynamic have varying effects on power-sharing systems; therefore, when considering power-sharing systems without looking at the powers that are shared and how these powers can be enforced (or not), care must be taken not to stop short of determining the crux of the matter for all matters related to power-sharing.

Performance

We still have an empirically incomplete picture of power-sharing in Southeastern Europe (and also in many other cases). Institutional design is often viewed as something opaque where we explore the institutional set up on one side and the state of interethnic relations on the other. However, we need to understand in greater detail how these institutions work in practice and what this tells us about their impact on interethnic relations.

7UNDP/Oxford Research International, The Silent Majority Speaks. Snapshots of Today and Visions of the Future of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Main Report, Quantitative Survey. Sarajevo 2007, 29, available at <http://www.undp.ba/?PID=7&RID=413>. All cited internet sources were last accessed on 06.12.2012. 8See more on this in Florian Bieber, Building Impossible States? State-Building Strategies and EU Membership in the Western Balkans, Europe-Asia Studies 63 (2011), n.10, 1783-1802.

Reconceptualizing the Study of Power-Sharing

531

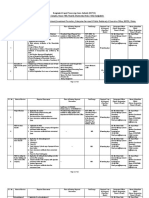

This can be best illustrated by the use of veto powers. Veto powers constitute one of the essential and yet most controversial features of power-sharing. Smaller groups are able to block all or just certain decisions if they appear to negatively affect the interests of these groups. Lijphart called them the ultimate weapon that minorities need to protect their vital interests.9 Schneckener distinguishes between direct, indirect and delaying veto powers in consociational systems.10 Bosnia has direct veto powers by allowing the representatives of the constituent peoples in parliament to evoke a violation of the vital interests of the community. Macedonia has an indirect veto right as certain key laws require not just asimple parliamentary majority, but also amajority of votes from the non-majority communities, which de facto gives the Albanian community the possibility to block legislation. In Kosovo, similarly, certain laws require both consent from the majority in parliament and the majority of non-dominant communities, giving the Serb community the possibility to veto certain laws. Amidst the perception that ethnicity and blockage in the political system go together, one would expect wide usage of these veto mechanisms by smaller communities to block decisions. However, the reality is quite different. In Bosnia, the vital interest veto has been used only in four cases between 1996 when the Dayton constitution came into effect and 2011. Similarly, veto rights in Macedonia and Kosovo have not led to the blockage of legislation in parliament since these mechanisms came into effect (in 2001 and 2008 respectively). The reasons for the limited use of veto powers differ. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the main veto player, the Republika Srpska, possesses amore effective veto mechanism, namely the ability to block any legislation at any reading in both chambers of parliament if two thirds or more of the MPs from either the Republika Srpska or the Federation do not support the law. Unlike the vital interest veto, this mechanism is not subject to amediation procedure and review by the constitutional court. Thus, 52.3% of all legislative acts in the Bosnian parliament between 1996 and 2007 failed due to the entity veto.11 In Macedonia and Kosovo, on the other hand, the inclusion of aminority party in government meant that legal acts in parliament had support of the parliamentary majority and thus the veto mechanism had little relevance in comparison to informal practices of cooperation in the executive branch.

9Arend Lijphart, The Power-Sharing Approach, in: Joseph Montville (ed.), Conflict and Peacemaking in Multiethnic Societies. New York 1991, 491-510, 495. 10Ulrich Schneckener, Making Power-Sharing Work: Lessons from Successes and Failures in Ethnic Conflict Regulation, Journal of Peace-Research 39 (2002), n.2, 203-228, 221f. 11Kasim Trnka/Merima Talovi/Ivana Mari, Evaluacija procesa odluivanja u Parlamentarnoj Skuptini BiH, 1996-2007. godine, in: Kasim Trnka et al., Proces odluivanja u Parlamentarnoj Skuptini Bosne i Hercegovine. Stanje komparativna rjeenja prijedlozi. Sarajevo 2009 (Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, BiH), 77-100, 89, available at <http://www.kas.de/ wf/doc/kas_17300-1522-15-30.pdf?090806160920>.

532

Florian Bieber

As a result, we can observe a significant discrepancy between the formal institutional set-up and expected dynamics of aconsociational system and the empirically observed reality. This highlights the need to understand not just the formal institutional structures but also the practice, often based on informal patterns that are not easily mapped out in formal decisions and documents.

Institutional Innovation

Institutional design rarely follows academic debates, and scholarly advice is often ignored. The global prevalence of power-sharing systems in internationally brokered peace plans has less to do with academic interest or advocacy and more with improvisation of international mediators and, at best, learning from previous peace plans. Very often, the peace agreements seem to follow many of the prescriptions of power-sharing, such as the idea of representation of all major groups, veto rights, agrand coalition, and group autonomy. However, there have been some additional aspects that have evolved in practice that have not yet been appropriately captured by most scholars of power-sharing, especially in light of the emerging concept of complex powersharing. When considering that this argues for multidimensional institutional arrangements, including international involvement and more features than the original West European models of consociationalism, these institutional innovations are significant. Here, two related features in Macedonia and Kosovo are noteworthy. In the absence of formal territorial autonomy or full cultural autonomy for minority groups, both countries devolved powers to municipalities which were re-drawn to empower minority groups at the local level. Whereas in Kosovo new municipal boundaries formalized existing territorial segregation, in Macedonia new municipalities were established to ensure that in contested regions local minorities constitute at least 20% of the population of the municipality in order to enjoy certain rights. Thus, in addition to decentralization, there are municipal mechanisms of minority inclusion that could be considered to be local powersharing. Overall, their performance has been weak because local authorities have limited capacities and they are beset by alack of oversight by the state as well as the activities of international players. Similarly, decentralization in Macedonia has been undermined by astrong central government using its discretion in funding municipalities. Thus, the Ohrid Framework Agreement has been formally implemented, but the inability of municipalities to secure their own funding reduced their ability in practice to act autonomously.12

12See Aisling Lyon, Between the Integration and Accommodation of Ethnic Difference: Municipal Decentralization in the Republic of Macedonia, Journal on Ethnopolitics and Minority Issues in Europe 12 (2012).

Reconceptualizing the Study of Power-Sharing

533

These difficulties aside, the inclusion of municipalities both as adimension of decentralization and alocus of power-sharing marks asignificant addition to the scope of power-sharing and the conventional state-centred approach of scholarship on power-sharing.

The Strange Gap between Local and International Debates on Power Sharing

Bosnia, Kosovo, and Macedonia have been discussed by scholars either critical or supportive of international efforts to strengthen post-war states as examples of power-sharing and state-building ever since their establishment. However, these studies have often been devoid of voices from the countries in question. The insider experience on how these institutions are perceived, experienced, and function in practice, as well as domestic controversies, do not shape international academic debates. By contrast, key international texts on power-sharing are usually included in domestic debates but more recent studies of the countries are generally not widely read, translated or debated. In effect, there are two parallel debates about power-sharing and state-building going on in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Macedonia and to alesser degree Kosovo. The cause for this gap is in part of atechnical nature: few scholars of powersharing would know the languages in question, especially if looking at cases in abroader comparative perspective. Similarly, few scholars from the region, unless they have studied or worked abroad, publish in English-language journals or books. Furthermore, international scholarship on state-building and power-sharing is not widely available in the region and few texts have been translated. To illustrate this dynamic, we shall briefly look at the Bosnian debate on power-sharing. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the debates only began after aten-year delay. The late debate on power-sharing in Bosnia might at first seem surprising, considering the profound impact that the new political system had. Only in the mid-2000s, ten years after Dayton, did Bosnia come to be analysed and debated from the perspective of political systems in general, and power-sharing in particular.13 The debate was triggered by the first (internationally negotiated) efforts to amend the constitution in late 2005 and in early 2006, which narrowly failed in the Bosnian parliament in April 2006. Although this process was not conducted publicly and Bosnian scholars had amarginal role, it drew attention for the first time to the technical details of the political system and the options for change.14

13Esad Zgodi, Vladavina Konsensusom. Sarajevo 2006. Zgodi discusses consensus democracy and its relevance for Bosnia. However, the book makes only scant reference to international academic debates on power-sharing or consociationalism. 14Ivan Lovrenovi, Silajdi i HDZ 1990, Dani, 05.05.2006.

534

Florian Bieber

A second trigger was the first major book in Croatian (Serbian/Bosnian) on Bosnian consociationalism written by the well-known Croatian political scientist and commentator Mirjana Kasapovi.15 While anumber of Western scholars and Bosnian scholars had previously written in Western languages about the consociational system in Bosnia, Kasapovis book was the first such study widely accessible to aBosnian readership. The debate that ensued focused both on the descriptive and the prescriptive aspects of power-sharing.16 Kasapovi argues in her book not only that power-sharing is an appropriate political system for Bosnia, but also that the Dayton system was an incomplete power-sharing system. She argues that historically, social and political life in Bosnia has been organised along religious and later ethnonational lines. The main change of the 1992-1995 war has been, in her mind, the territorialisation of ethnonationalist affiliation, reducing the choices for apolitical system. Thus,

Bosnia and Herzegovina is not sustainable as a non-ethnic or administrative federation, nor can its ethnic groups be satisfied with some type of unemotional regionalism implemented in some Western nation state.17

The Dayton arrangement in the eyes of Kasapovi is an imperfect consociation as it does not attribute equal group rights. Serbs and Bosniaks enjoy de facto territorial autonomy, whereas Croats are only aminority in one entity, the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina.18 In particular, the latter suggestion, implying the establishment of athird (Croat) entity in Bosnia and Herzegovina, has been the source of controversy in the debates and also tainted the term consociation as being aconcept associated with the position of Croat national parties. Kasapovis position found supporters and critics in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Critics focused on three aspects. First, some scholars and commentators challenged the characterization of Bosnia as asociety shaped by deep religious and ethnonational divisions pre-dating the Dayton accords. Second, others, including the Swiss political scientist of Bosnian origin Nenad Stojanovi, challenged the view that Bosnia was not afully-fledged consociational system, arguing instead that Bosnia is an example of consociationalism par excellence.19 Third, critics focused on whether consociationalism is an appropriate model for Bosnia at all. The most articulate critique came from Azim Mujki, from the

15Mirjana Kasapovi, Bosna i Hercegovina: podijeljeno drutvo i nestabilna drava. Zagreb 2005. 16The debate took place primarily in the weekly Dani, the daily Oslobodjenje and the academic magazine Status. 17Mirjana Kasapovi, Bosna i Hercegovina: Deset godina nakon Daytona, Status (2006), n.9, 44-73, 70. 18Ibid., 68f. 19Interview with Nenad Stojanovi, Uredjenje BiH i vicarske je neuporedivo, Slobodna Bosna, 18.10.2007, 34. Asimilar view is experessed by Zlatko Hadidedi, Kako izvan granica miletske paradigme, Nezavisne novine, 27.09.2007, 10.

Reconceptualizing the Study of Power-Sharing

535

Faculty of Political Science at the University of Sarajevo. He argued that the ethnocratic system governing Bosnia and Herzegovina is incompatible with liberal democracy. Besides arguing that the state should practice benign indifference towards ethnonational identity, he also suggests that consociationalism encompasses an ethnofederal arrangement of the country that is aprelude to state disintegration. He explicitly rejects the possibility that consociationalism can tame nationalism and rather draws on Roger Brubaker to argue that the consociational system is reifying exclusionary ethnic practices.20 In addition to this largely normative debate on power-sharing, empirical studies have shed adifferent light on the functioning of institutions, such as the aforementioned analysis of the use of vetoes.21 Through this brief discussion of inner-Bosnian debates and studies of power-sharing, Iargue that the state-building and power-sharing literature needs to move away from studying countries without also including local scholarship on power-sharing and assessing the perception of power-sharing in the domestic academic arena. The domestic understandings of power-sharing are fundamental not only in providing empirical richness to any study of power-sharing, but also for exploring normative perceptions of power-sharing in its particular context. As aresult, the domestic debates about power-sharing do not just enrich the larger discussions about this system of governments, but they also shed light on its legitimacy and the practices of power-sharing that are often substantially different from the mere legal framework. These five dimensions of studying power-sharing in Southeastern Europe help to broaden the understanding of state-building and particular institutional approaches by including the context, from the historical to the academic. This article thus suggests that there is a need for greater academic cooperation between researchers with local knowledge, including languages, debates, and background and scholars with acomparative focus.

20Asim

21Trnka/Talovi/Mari,

Mujki, We, the Citizen of Ethnopolis. Sarajevo 2008, 149-183. Evaluacija procesa odluivanja (above fn.11).

You might also like

- Constitutionalizing Democracy in Fractured SocietiesDocument22 pagesConstitutionalizing Democracy in Fractured SocietiesLuiz Fernando FerreiraNo ratings yet

- F 2010alocal RegionalStateDocument17 pagesF 2010alocal RegionalStateddsdfNo ratings yet

- Is The Nation State Losing Its Relevance?Document5 pagesIs The Nation State Losing Its Relevance?ilginbaharNo ratings yet

- The Global Commonwealth of Citizens: Toward Cosmopolitan DemocracyFrom EverandThe Global Commonwealth of Citizens: Toward Cosmopolitan DemocracyNo ratings yet

- Represent in Trans Web 09Document26 pagesRepresent in Trans Web 09yanari2No ratings yet

- Comparative Political StudiesDocument31 pagesComparative Political StudiesAna Maria Ungureanu-IlincaNo ratings yet

- Federalism and Political ParticipationDocument9 pagesFederalism and Political ParticipationGabriel TorresNo ratings yet

- Gagyi - Coloniality of PowerDocument24 pagesGagyi - Coloniality of PowerLika RodinNo ratings yet

- Historical Development PDFDocument36 pagesHistorical Development PDFsangeetaNo ratings yet

- Theories of FederalismDocument3 pagesTheories of FederalismSwechha SinghNo ratings yet

- Organizing Democracy: How International Organizations Assist New DemocraciesFrom EverandOrganizing Democracy: How International Organizations Assist New DemocraciesNo ratings yet

- Weak Civil Society in CEECDocument8 pagesWeak Civil Society in CEECKristin KretzschmarovaNo ratings yet

- Botakoz Kasumbekova European Resttlement in TJK 2011Document18 pagesBotakoz Kasumbekova European Resttlement in TJK 2011amudaryoNo ratings yet

- Classic Article For Individual EssayDocument13 pagesClassic Article For Individual Essaymishal chNo ratings yet

- Judicial Unification in Post Colonial IndonesiaDocument38 pagesJudicial Unification in Post Colonial Indonesiaahmadshalahudin31No ratings yet

- 2.4 - Markovic, Mihailo - Self-Governing Political System and De-Alienation in Yugoslavia (1950-1965) (En)Document17 pages2.4 - Markovic, Mihailo - Self-Governing Political System and De-Alienation in Yugoslavia (1950-1965) (En)Johann Vessant RoigNo ratings yet

- Consociational Experiments in The Western Balkans: Bosnia and Herzegovina and MacedoniaDocument22 pagesConsociational Experiments in The Western Balkans: Bosnia and Herzegovina and MacedoniaTalha khalidNo ratings yet

- Contentious Politics in New Democracies: Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, & The Former East Germany (PSGE 41 1997) Grzegorz Ekiert & Jan KubikDocument50 pagesContentious Politics in New Democracies: Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, & The Former East Germany (PSGE 41 1997) Grzegorz Ekiert & Jan KubikMinda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies at Harvard UniversityNo ratings yet

- Wounded AttachmentsDocument22 pagesWounded AttachmentsMichael van der VeldtNo ratings yet

- Dembinska FrozenConflictsInternal 2017Document26 pagesDembinska FrozenConflictsInternal 2017epirrysNo ratings yet

- Regional Autonomy and State Paradigm Shifts in Western EuropeDocument26 pagesRegional Autonomy and State Paradigm Shifts in Western Europejunaidtvpk92No ratings yet

- Democracy in Central Asia: Competing Perspectives and Alternative StrategiesFrom EverandDemocracy in Central Asia: Competing Perspectives and Alternative StrategiesNo ratings yet

- Dolenec Zitko Socialist CommonsDocument11 pagesDolenec Zitko Socialist CommonsJerko BakotinNo ratings yet

- Consociation and Voting in Northern Ireland: Party Competition and Electoral BehaviorFrom EverandConsociation and Voting in Northern Ireland: Party Competition and Electoral BehaviorNo ratings yet

- Constitutions and Conflict Management in Africa: Preventing Civil War Through Institutional DesignFrom EverandConstitutions and Conflict Management in Africa: Preventing Civil War Through Institutional DesignNo ratings yet

- Varieties of Statehood: Russia's Transformation and The Energy Charter Regime (1991-2010)Document54 pagesVarieties of Statehood: Russia's Transformation and The Energy Charter Regime (1991-2010)RoxanneNo ratings yet

- Good Governance, Democratic Societies and Globalisation by SurendraDocument5 pagesGood Governance, Democratic Societies and Globalisation by SurendraMohd AsifNo ratings yet

- 1 A-2 Mann - Concept of Infrastructural PowerDocument11 pages1 A-2 Mann - Concept of Infrastructural Powerrichiflowers11gmail.comNo ratings yet

- Immergut 2010Document14 pagesImmergut 2010a.wirapranathaNo ratings yet

- Recognising Politics in Unrecognised StaDocument14 pagesRecognising Politics in Unrecognised StaAna PatsatsiaNo ratings yet

- Ideologies of AutocratizationDocument24 pagesIdeologies of Autocratization李小四No ratings yet

- Florian Bieber, Power Sharing As Ethnic Representation in Post-Conflict Societies: The Cases of Bosnia, Macedonia and KosovoDocument19 pagesFlorian Bieber, Power Sharing As Ethnic Representation in Post-Conflict Societies: The Cases of Bosnia, Macedonia and KosovoFlorian BieberNo ratings yet

- The Rentier State in The Middle EastDocument34 pagesThe Rentier State in The Middle EastbengersonNo ratings yet

- State Society Relations JMS 20090731Document40 pagesState Society Relations JMS 20090731SiwangoNo ratings yet

- Ssia - Nikolaos.nikolakakis LibreDocument9 pagesSsia - Nikolaos.nikolakakis LibreJames GohNo ratings yet

- Leader Cult and HoxhaDocument17 pagesLeader Cult and HoxhaPascale Gallagher100% (1)

- Tau Reck 2006Document3 pagesTau Reck 2006ManaiNo ratings yet

- Constrained Democracy: The Consolidation of Democracy in Yugoslav Successor States by Florian Bieber and Irena RisticDocument25 pagesConstrained Democracy: The Consolidation of Democracy in Yugoslav Successor States by Florian Bieber and Irena RisticFlorian BieberNo ratings yet

- List of Changes File (Final) 'Document7 pagesList of Changes File (Final) 'Wassihun GebreegziabherNo ratings yet

- Wimmer Three Models 2012Document56 pagesWimmer Three Models 2012Lhda DwdouNo ratings yet

- Michael Mann The Autonomous Power of The State PDFDocument30 pagesMichael Mann The Autonomous Power of The State PDFSebastienGarnierNo ratings yet

- Capitalist Development and Democracy - NotesDocument6 pagesCapitalist Development and Democracy - NotesAndreea MarinaNo ratings yet

- YUHUA WANG, State-In-Society 2.0 Toward Fourth Generation Theories of StateDocument24 pagesYUHUA WANG, State-In-Society 2.0 Toward Fourth Generation Theories of Statealiyanashwa7No ratings yet

- State FormationDocument23 pagesState FormationSyarif Rukmana100% (2)

- Concepts of The Nation and Legitimation in Belarus: November 2015Document16 pagesConcepts of The Nation and Legitimation in Belarus: November 2015Arijan MilicNo ratings yet

- Concept Paper CompiledDocument75 pagesConcept Paper CompiledGroup 5 PolSci 3B ThesisNo ratings yet

- State Formation - Political Science - Oxford BibliographiesDocument28 pagesState Formation - Political Science - Oxford BibliographiesEsteban RozoNo ratings yet

- Mitchell, Timothy. 1991. The Limits of The State: Beyond Statist Approaches and Their Critics'Document6 pagesMitchell, Timothy. 1991. The Limits of The State: Beyond Statist Approaches and Their Critics'Arushi SharmaNo ratings yet

- O'Donnell, G. (1993) - On The State, Democratization and Some Conceptual ProblemsDocument15 pagesO'Donnell, G. (1993) - On The State, Democratization and Some Conceptual ProblemsAgencija SpektarNo ratings yet

- Logics of Hierarchy: The Organization of Empires, States, and Military OccupationsFrom EverandLogics of Hierarchy: The Organization of Empires, States, and Military OccupationsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- States of Injury: Power and Freedom in Late ModernityFrom EverandStates of Injury: Power and Freedom in Late ModernityRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (14)

- Contrasting Unitary Federal Form of GovtDocument16 pagesContrasting Unitary Federal Form of GovtUtkarsh singhNo ratings yet

- Aproaches To National Minority PolicyDocument11 pagesAproaches To National Minority Policyapi-269786551No ratings yet

- Constrained Democracy: The Consolidation of Democracy in Yugoslav Successor States by Florian Bieber and Irena RisticDocument25 pagesConstrained Democracy: The Consolidation of Democracy in Yugoslav Successor States by Florian Bieber and Irena RisticFlorian BieberNo ratings yet

- Florian Bieber, Interethnic Relations Southeastern EuropeDocument16 pagesFlorian Bieber, Interethnic Relations Southeastern EuropeFlorian BieberNo ratings yet

- Florian Bieber: From Nationalities To Diversity: How To Keep Nationalities Papers RelevantDocument6 pagesFlorian Bieber: From Nationalities To Diversity: How To Keep Nationalities Papers RelevantFlorian BieberNo ratings yet

- Florian Bieber, Book Review Essay, Perspectives On PoliticsDocument4 pagesFlorian Bieber, Book Review Essay, Perspectives On PoliticsFlorian BieberNo ratings yet

- The Role of The Framework Convention For The Protection Ofnational Minorities in Selectedcountries of South-Eastern Europeafter Two Monitoring CyclesDocument15 pagesThe Role of The Framework Convention For The Protection Ofnational Minorities in Selectedcountries of South-Eastern Europeafter Two Monitoring CyclesFlorian BieberNo ratings yet

- Of Balkan Apples, Oranges, Grandmothers and Frogs. Comparative Politics and The Study of Southeastern EuropeDocument11 pagesOf Balkan Apples, Oranges, Grandmothers and Frogs. Comparative Politics and The Study of Southeastern EuropeFlorian BieberNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Special Issue Special Issue: Unconditional Conditionality? The Impact of EU Conditionality in The Western BalkansDocument8 pagesIntroduction To The Special Issue Special Issue: Unconditional Conditionality? The Impact of EU Conditionality in The Western BalkansFlorian BieberNo ratings yet

- Florian Bieber, The Challenge of Institutionalizing Ethnicity in The Western BalkansDocument20 pagesFlorian Bieber, The Challenge of Institutionalizing Ethnicity in The Western BalkansFlorian BieberNo ratings yet

- Florian Bieber, Montenegro in Transition. Problems of Statehood and IdentityDocument196 pagesFlorian Bieber, Montenegro in Transition. Problems of Statehood and IdentityFlorian BieberNo ratings yet

- Florian Bieber, Territory, Identity and The Challenge of Serbia's EU IntegrationDocument6 pagesFlorian Bieber, Territory, Identity and The Challenge of Serbia's EU IntegrationFlorian BieberNo ratings yet

- Florian Bieber, Holly Case, Eds., The Global 1989Document7 pagesFlorian Bieber, Holly Case, Eds., The Global 1989Florian BieberNo ratings yet

- Florian Bieber, Regulating Minority Parties in Central and Southeastern EuropeDocument18 pagesFlorian Bieber, Regulating Minority Parties in Central and Southeastern EuropeFlorian BieberNo ratings yet

- Florian Bieber, Stefan Wolff, Introduction. Elections in Divided SocietiesDocument6 pagesFlorian Bieber, Stefan Wolff, Introduction. Elections in Divided SocietiesFlorian BieberNo ratings yet

- Florian Bieber, Creating An Ethnic PeaceDocument3 pagesFlorian Bieber, Creating An Ethnic PeaceFlorian BieberNo ratings yet

- Florian Bieber, Local Institutional Engineering: A Tale of Two Cities, Mostar and BrckoDocument15 pagesFlorian Bieber, Local Institutional Engineering: A Tale of Two Cities, Mostar and BrckoFlorian BieberNo ratings yet

- Florian Bieber, Review of Sundhaussen, Geschichte SerbiensDocument2 pagesFlorian Bieber, Review of Sundhaussen, Geschichte SerbiensFlorian BieberNo ratings yet

- Florian Bieber, The Role of The Yugoslav People's Army in The Dissolution of Yugoslavia-The Army Without A State?Document20 pagesFlorian Bieber, The Role of The Yugoslav People's Army in The Dissolution of Yugoslavia-The Army Without A State?Florian BieberNo ratings yet

- Florian Bieber, Lessons From The European Union For Institutional Design in Multinational StatesDocument6 pagesFlorian Bieber, Lessons From The European Union For Institutional Design in Multinational StatesFlorian BieberNo ratings yet

- Florian Bieber, Approaches To Political Violence and Terrorism in Former YugoslaviaDocument14 pagesFlorian Bieber, Approaches To Political Violence and Terrorism in Former YugoslaviaFlorian BieberNo ratings yet

- Florian Bieber, Serbia: Minorities in A Reluctant StateDocument8 pagesFlorian Bieber, Serbia: Minorities in A Reluctant StateFlorian BieberNo ratings yet

- Florian Bieber, After Dayton, Dayton? The Evolution of An Unpopular PeaceDocument18 pagesFlorian Bieber, After Dayton, Dayton? The Evolution of An Unpopular PeaceFlorian BieberNo ratings yet

- Florian Bieber, Power Sharing As Ethnic Representation in Post-Conflict Societies: The Cases of Bosnia, Macedonia and KosovoDocument19 pagesFlorian Bieber, Power Sharing As Ethnic Representation in Post-Conflict Societies: The Cases of Bosnia, Macedonia and KosovoFlorian BieberNo ratings yet

- Florian Bieber, Power Sharing After Yugoslavia. Functionality and Dysfunctionality of Power Sharing Institutions Post-War Bosnia, Macedonia and KosovoDocument23 pagesFlorian Bieber, Power Sharing After Yugoslavia. Functionality and Dysfunctionality of Power Sharing Institutions Post-War Bosnia, Macedonia and KosovoFlorian BieberNo ratings yet

- Florian Bieber, The Legal Framework For Post-War Kosovo and The Myth of MultiethnicityDocument22 pagesFlorian Bieber, The Legal Framework For Post-War Kosovo and The Myth of MultiethnicityFlorian BieberNo ratings yet

- Florian Bieber, Montenegro in Transition. Problems of Statehood and IdentityDocument196 pagesFlorian Bieber, Montenegro in Transition. Problems of Statehood and IdentityFlorian BieberNo ratings yet

- Florian Bieber, Nationalist Mobilization and Stories of Serb Suffering: The Kosovo Myth From 600th Anniversary To The PresentDocument16 pagesFlorian Bieber, Nationalist Mobilization and Stories of Serb Suffering: The Kosovo Myth From 600th Anniversary To The PresentFlorian BieberNo ratings yet

- Florian Bieber, Delayed Transition and The Multiple Legitimacy Crisis of Post-1992 YugoslaviaDocument26 pagesFlorian Bieber, Delayed Transition and The Multiple Legitimacy Crisis of Post-1992 YugoslaviaFlorian BieberNo ratings yet

- Florian Bieber, The Serbian Opposition and Civil Society: Roots of The Delayed Transition in SerbiaDocument18 pagesFlorian Bieber, The Serbian Opposition and Civil Society: Roots of The Delayed Transition in SerbiaFlorian BieberNo ratings yet

- Florian Bieber, Pluralism and Complex Power-Sharing in Post-Conflict Societies: The Case of Bosnia and HerzegovinaDocument10 pagesFlorian Bieber, Pluralism and Complex Power-Sharing in Post-Conflict Societies: The Case of Bosnia and HerzegovinaFlorian BieberNo ratings yet

- Residential Status PDFDocument14 pagesResidential Status PDFPaiNo ratings yet

- Freedom Essay RebootDocument5 pagesFreedom Essay RebootRaj singhNo ratings yet

- The Argumentative Indian Amartya SenDocument12 pagesThe Argumentative Indian Amartya SenVipin Bajaj100% (2)

- Call CenterDocument25 pagesCall Centerbonika08No ratings yet

- PAC - BABE - UserManualDocument15 pagesPAC - BABE - UserManualAvinash AviNo ratings yet

- Core ScientificDocument8 pagesCore ScientificRob PortNo ratings yet

- Law University SynopsisDocument3 pagesLaw University Synopsistinabhuvan50% (2)

- Memorandum Shall Be A Ground For Dismissal of The AppealDocument4 pagesMemorandum Shall Be A Ground For Dismissal of The AppealLitto B. BacasNo ratings yet

- Orders, Decorations, and Medals of The Malaysian States and Federal Territories PDFDocument32 pagesOrders, Decorations, and Medals of The Malaysian States and Federal Territories PDFAlfred Jimmy UchaNo ratings yet

- Ed2 Project Eklavya ApplicationForm August 2020Document23 pagesEd2 Project Eklavya ApplicationForm August 2020Shourya GargNo ratings yet

- Bangladesh Export Processing Zones AuthorityDocument16 pagesBangladesh Export Processing Zones AuthoritySohel Rana SumonNo ratings yet

- SECULAR Vs Islm ComparisonDocument2 pagesSECULAR Vs Islm ComparisonAsif SaeedNo ratings yet

- Libcompiler Rt-ExtrasDocument2 pagesLibcompiler Rt-ExtrasNehal AhmedNo ratings yet

- Britannia: Business Conduct (COBC) For Its Employees. This Handbook Covers The CodeDocument17 pagesBritannia: Business Conduct (COBC) For Its Employees. This Handbook Covers The CodevkvarshakNo ratings yet

- Document View PDFDocument4 pagesDocument View PDFCeberus233No ratings yet

- United States v. Mark Bowens, 4th Cir. (2013)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Mark Bowens, 4th Cir. (2013)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Going Through Customs: Useful WordsDocument1 pageGoing Through Customs: Useful Wordslolita digiacomoNo ratings yet

- Centrifugally Cast White Iron/Gray Iron Dual Metal Abrasion-Resistant Roll ShellsDocument2 pagesCentrifugally Cast White Iron/Gray Iron Dual Metal Abrasion-Resistant Roll ShellsGustavo SuarezNo ratings yet

- KashmirDocument58 pagesKashmirMahamnoorNo ratings yet

- 16+ Zip Oyster Photocard Terms and ConditionsDocument9 pages16+ Zip Oyster Photocard Terms and ConditionsTTMo1No ratings yet

- 016-7100-039-A - Raven RCM Installation Manual - Retrofit Conversion From AragDocument24 pages016-7100-039-A - Raven RCM Installation Manual - Retrofit Conversion From AragAlex RosaNo ratings yet

- Statement of Account: Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing BalanceDocument4 pagesStatement of Account: Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing Balancepavans25No ratings yet

- Week 13 - Local Government (Ra 7160) and DecentralizationDocument4 pagesWeek 13 - Local Government (Ra 7160) and DecentralizationElaina JoyNo ratings yet

- Mohnish Pabrai - ChecklistDocument1 pageMohnish Pabrai - ChecklistCedric TiuNo ratings yet

- IA I Financial Accounting 3B MemoDocument5 pagesIA I Financial Accounting 3B MemoM CNo ratings yet

- Common Accounting Concepts and Principles: Going ConcernDocument3 pagesCommon Accounting Concepts and Principles: Going Concerncandlesticks20201No ratings yet

- 01 Internal Auditing Technique Rev. 05 12 09 2018Document40 pages01 Internal Auditing Technique Rev. 05 12 09 2018Syed Maroof AliNo ratings yet

- American Bible Society v. City of Manila DigestsDocument4 pagesAmerican Bible Society v. City of Manila Digestspinkblush717100% (3)

- 06 - StreamUP & Umap User ManualDocument98 pages06 - StreamUP & Umap User ManualRené RuaultNo ratings yet

- SSU KL Fee Schedule AY23!24!1 NovDocument1 pageSSU KL Fee Schedule AY23!24!1 NovAisyah NorzilanNo ratings yet