Professional Documents

Culture Documents

658845

Uploaded by

Maria Antonietta RicciOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

658845

Uploaded by

Maria Antonietta RicciCopyright:

Available Formats

The Ancient Egyptian Book of Thoth: A Demotic Discourse on Knowledge and Pendant to the Classical Hermetica, by Richard Jasnow

and Karl-Th. Zauzich. The Ancient Egyptian Book of Thoth: A Demotic Discourse on Knowledge and Pendant to the Classical Hermetica by Richard Jasnow; Karl-Th. Zauzich Review by: Ghislaine Widmer Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 70, No. 1 (April 2011), pp. 113-116 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/658845 . Accessed: 17/03/2013 16:41

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Near Eastern Studies.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded on Sun, 17 Mar 2013 16:41:26 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Book Reviews F113

may originally have represented a procession of gods before Ptah since only the latter faces left while all the other gods face right. As far as the date is concerned, it is suggested that the text is early Ptolemaic and the vignettes are perhaps late Ptolemaic or early Roman. The fragments are reproduced in beautiful color plates (pls. 4148). Through the bibliographical database Trismegistos2 I have come across two demotic items that seem to have been overlooked. Both are bilingual texts, one a Greek/demotic/hieratic mummy label (Brooklyn 16.644 = TM 16388) and the other a Greek/demotic receipt for the payment of salt tax (Brooklyn 12768 1648 = O. Wilb. 1 = TM 50412). The omission of the former is surprising since Hughes himself provided a translation of the demotic text for K. Herbert, Greek and Latin Inscriptions in the Brooklyn Museum (Brooklyn, 1972), 3738, pl. 12; cf. note 1. The catalog of texts is followed by lists of datable texts in chronological order and regnal years of unknown rulers as well as four concordances: catalog numbers, Brooklyn Museum accession numbers, New York Historical Society inventory numbers, and C. E. Wilbour serial numbers. A few accession numbers are missing from Concordance 2 (p. 94): acc. no. 16.580.260 (Wilbour serial no. [12768] 1754; Cat. no. 73), acc. no. 16.580.261 (Wilbour serial no.

2 http:/ /www.trismegistos.org. The Trismegistos reference numbers cited are prexed TM.

[12768] 1568; Cat. no. 74), acc. no. 16.580.305 (Wilbour serial no. [12768] 1632; Cat. no. 180), acc. no. 16.644 (text not included in the catalog; TM 16388; see above), and acc. no. 37.1647E (Cat. no. 213); and a single Wilbour number is missing in Concordance 4 (p.96): Wilbour serial no. (12768) 1648 (text not included in the catalog; TM 50412, cf. above). The volume concludes with detailed indexes of selected words and phrases, divine names, place names, personal names, and proveniences of texts (pp. 97115), followed by forty-six plates, the last ten of which are in color (cat. no. 213). It is unfortunate that neither the many improved readings suggested by Brian Muhs, nor the suggested readings by K.-Th. Zauzich that are cited in the original notes, have been incorporated into the indexes. The volume provides a good overview of the demotic material in the Brooklyn Museum. It does have a number of bibliographical shortcomings, and, as mentioned, it is regrettable that certain items are not reproduced in the plates, above all the numerous ostraca that are translated for the rst time. There are still batches of numerous smaller, unsorted fragments that remain to be studied, but it was not the purpose of the catalog to present a detailed study of every item, and we should be grateful to the author for turning the catalog into something more than a mere checklist.

The Ancient Egyptian Book of Thoth: A Demotic Discourse on Knowledge and Pendant to the Classical Hermetica. By Richard Jasnow and Karl-Th. Zauzich. Vol. 1, Text. Vol. 2, Plates. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2005. Pp. xx + 581 + 67 pls. REVIEWED BY GHISLAInE WIDmEr, Universit de Lille. The Book of Thoth is the name given by its editors to a collection of papyri forming an extensive composition attested in several Demotic manuscriptsand (so far) one hieratic, two-columned papyrusfrom the Greco-Roman period. These fragmentary texts, scattered in various museum collections (Berlin, Copenhagen, Florence, New Haven, Paris, and Vienna), originate not only from the Fayumin particular Tebtynis and Soknopaiu Nesos/Dimebut apparently also from Upper Egypt, thus indicating a wide circulation for this composition. The book under review is the result of a titanic work started by K.-Th. Zauzich some forty years ago and carried on in collaboration with R. Jasnow since 1989; both authors deserve the highest praise for carrying it through and providing us with this valuable editio princeps.1

1 An extensive review of this book was recently published by J. Fr. Quack, Die Initiation zum Schreiberberuf im Alten gypten, SAK 36 (2007): 24995; because of space limits, I shall just refer to suggestions and comments made by the reviewer, without expanding on his arguments. See also J. Fr. Quack, Ein gyptischer Dialog ber die Schreibkunst und das arkane Wissen, AfP 9 (2007): 25994, and Fr. Hoffmann, BiOr LXV (2008), 8692.

This content downloaded on Sun, 17 Mar 2013 16:41:26 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

114 F Journal of Near Eastern Studies

The editors often emphasize that, because of the nature of the composition, its style, the condition of preservation of the papyri, and the fact that fragmentary texts continue to surface in museum collections, the contents are not easy to summarize. The composition is in the form of a dialoguemainly in a questionand-answer formatbetween a teacher or an examiner and his pupil. Learning and writing are central topics of the text, which might present connections with the Hermetic corpus. The original title of the Book of Thoth is apparently preserved in a unique fragment (B07, line 1): [The word]s which cause a youth to learn and a son of a Wen-ima to question.2 Because of the quantity of fragments and manuscript sources,3 the editors decided to use as a guideline the best preserved document (B02), which is also the oldest, dated paleographically to the rst century B.C. However, textual variants are frequent and the manuscript tradition is, as often with Egyptian literature, more creative than straightforward (p.132). The major papyri are designated according to their museum location (B01B14 = Berlin; L01L02 = Louvre; V01V04 = Vienna, etc.), with the additional fragments considered to be part of the same manuscriptno matter their present locationindicated as subgroups, for instance, B03.1, B03.2, etc. (list on pp. 7988). The translation and transliteration of each fragment are found on pages XIII to XV. The Ancient Egyptian Book of Thoth consists of two volumes. The plates (vol. 2), reproduced in a large format and supplied with concordance tables, are presented according to the alphabetical order of the papyri designation. The rst and most important part of the text volume (vol. 1) is devoted to introducing the recurring gures, places, animals, and plants (pp. 178); very cautious essays on contentious issues, such as initiation and mysticism (pp. 5461) as well as hermetism (pp. 6571), are also included. Part 2 deals with the description of the physical appearance of the manuscripts and their peculiarities, i.e., their orthography, script, grammar, and vocabulary

See Book of Thoth, 8 and 369, and Quack, SAK 36: 251. 3 According to the editors, fourty-four different manuscript sources could be distinguished, but they cautiously admitted that some of them may belong to the same papyrus roll (p.2). Quack, SAK 36: 26263, lowered the number to twenty-ve or thirty pieces.

2

(pp. 79132). The transliterations and translations are found in parts 3 and 4 (pp. 139471, including a tentative consecutive translation), supplied with several addenda (part 5). Volume 1 ends with detailed glossaries and a general index (pp. 497581). Because of its language and the complexity of its occurring themes (not to mention the problems in the reconstitution of the text), determining the contents and the real purpose of such a compositionwhich consists of at least 18 columns, according to B02is a major difficulty. The editors chose to call it the Book of Thoth, because they believe the main gure conducting the dialogue is a form of Thoth. J. Fr. Quack in his review argued that this gure might just be an examiner, as the god of writing is mentioned as an autonomous gure in the papyri.4 In fact, as pointed out by R. Jasnow and K.-Th. Zauzich, the text tends to avoid obvious names and titles, resorting instead to periphrases with archaic grammatical constructions; this elusiveness, which might be related to the Egyptian idea of restricted knowledge, seems to indicate that the composition was somehow intended for an elite group. Thus the dialogue takes place between He/one-who-loves-knowledge or, depending on the translation, He-who-wishes to learn (mr-r), i.e., the aspiring student, and So-he-says-(namely)He-of-Heseret (var. He-who-praises-knowledge) or, depending on the translation, So-he-says-in-Heseret/Hesrekh (r=f-n-Hr.t var. r =f-n-s-r), i.e., the examiner.5 The discursive form of the text and the hypothesis of the gure of Thoth as the divine instructor have led the authors to consider the relationship between this composition and the Hermetic corpus. Remaining very cautious, they stress the essential differences between both writings (p.70); although there are similarities in the general content, the Book of Thoth remains Egyptian in its nature: there is no verbal parallel, no evidence for uniquely Greek thought or distinctive Greek philosophical terminology (p.71).6

4 I would tend to agree with this hypothesis; cf. Quack, SAK 36: 250. 5 Heseret is the name of a necropolis near Hermopolis Magna. We should also note that the expression is not always followed by the divine determinative, as indicated by the authors on p. 9; in B02, for instance, it uses the geographical sign. 6 See also Quack, SAK 36: 261.

This content downloaded on Sun, 17 Mar 2013 16:41:26 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Book Reviews F115

Further participants break in on the dialogue, in particular He-created-the-thoughts and He-hasjudged-namely-the-one-who-is-upon-his-back/uponhis-standard,7 but since they are also designated by periphrases, their identication remains problematic. Seshat, the goddess of writing, is not explicitly named: she appears through one of her epithets, Sefekh-abui,8 and possibly as She-who-has-initiated (pp. 1923). Other unclear designations, for instance the craftsman or the assistant (pp. 3233), occur regularly in the discourse. Places are also named in a cryptic way. The chamber of darkness (pp. 3638) seems to be a concealed room accessible under certain conditions; it may denote an area in the underworld or a crypt.9 The mention of the secret compartments of Thoth is also remarkable, as it goes back to a long Egyptian literary tradition concerning a book of Thoth hidden in it (p.193). Thus, according to the Demotic tale of Setne I, reciting a spell from this work permits one to charm the sky, the earth, the netherworld, the mountains and the waters, as well as to understand the language of all animalsa theme also occurring in the Book of Thoth (pp. 4344).10 Despite the help of rubrics, the stichic layout of a few manuscripts, and the occurrence of verse points, the narrative reconstruction remains hypothetical. I shall describe just a few sections to give an idea of its remarkable metaphorical style, using a fecund imagery derived from the animal, vegetal, and mineral worlds. The rst column of the text is apparently devoted to the description of the state of renouncement that the pupil should embrace.11 The following sections are concerned with scribal art, including the way to hold the writing tool: Your three ngers, place the brush between them. Your two ngers, let them make a grasping [...] (B02, col. 5, line 13). To the question What is writing? (B02, col. 4, line 12), He-wholoves-knowledge is answered through a series of comFor this last suggestion, see Quack: SAK 36: 250. On this puzzling epithet, for which no denite translation is available, see D. Budde, Die Gttin Seschat, in Lexikon der gyptischen Gtter und Gtterbezeichnungen, ed. Christian Leitz. Kanobos 2. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta (Leipzig, 2000), 1324. 9 For the latter suggestion, see Quack, SAK 36: 26162. 10 As mentioned several times by the editors, Setne I bears notable similarities with The Book of Thoth; cf., for instance, p.76, n. 265. 11 For this interpretation, based on new readings and reconstructions of a rather damaged section, see Quack, SAK 36: 25152.

7 8

parisons and metaphors: writing is a sea (?) in which the student might be allowed to swim one day; its reeds are a shore (B02, col. 4, line 13). With shing and fowling images, the pupil is encouraged to gain knowledge (V01, col. 3), a desire he expresses metaphorically several times in the text: ... my mouth is open, may one give to it milk (B02. col. 6, line 7). Although this kind of imagery is at rst sight not very common in Egyptian literature, Ramesside scholastic texts often resort to similar comparisons to describe the superior advantages of the scribes profession and the immortality of writings. In papyrus Chester Beatty IV, v. 2,5v. 3,11, for instance, the teachings left by wise men are said to be their pyramids, the reedpen, their child, and the stone surface, their wife. In B02, column 7, line 10, the pupil recognizes with gratitude that he has acquired a special knowledge: You have caused that I achieve old age, I being (still) young. This long section appears to end with a hymn of praise to the foremost one of the temple of Ptah, in the festival of Imhotep, before Osiris-Neferhotep (B02, col. 8), possibly indicating that the text was used in a Memphite ritual context. However, once again, the gure mentioned here is not explicitly designated, leaving us with many open questions.12 The contents of the remaining columns are hard to summarize; He-who-loves-knowledge seems to demonstrate knowledge in sacred terminology and geography, as in the so-called Vulture Text (V.T., pp. 33258), a section available in essentially one version (L01), where the disciple names and describes (from south to north) forty-two vultures corresponding to the forty-two Egyptian nomes. The end of the text is not preserved. The so-called Book of Thoth appears to be a scholastic work written for and by priests in the context of the House of Life (p.77). Although the text was probably written in Demotic, it was compiled at some point in the Ptolemaic Period, drawing on varied sources.13 The resort to such a metaphorical style,

For the relative importance of Imhotep in our text (in connection with the Famine Stela) and the intriguing mentions of OsirisNeferhotep (a divine form attested mainly in the region of Hu, in Middle Egypt), see Book of Thoth, 1719 and Quack, SAK 36: 26061. 13 According to the editors (p.77), the compilation most probably took place in the later Ptolemaic or early Roman Period; for a slightly different point of view, see Quack, SAK 36: 262.

12

This content downloaded on Sun, 17 Mar 2013 16:41:26 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

116 F Journal of Near Eastern Studies

supplied with numerous plays on words, makes one wonder whether it was not one of the purposes of the composition to illustrate the possibilities of word play, or to impress on the student the potential for puns embodied in the Egyptian language (p.114). In view of this, my deepest regret lies in the absence of facsimiles in the glossaries, a task I realize would have been troublesome because of the number of manuscript sources. However, confronting the different hands and orthographies would no doubt have been of great help in bringing out, for instance, the variations in the determinatives and identifying the paleographic

peculiarities of each scribe as well as, possibly, each temple school.14 In conclusion, I would like to reiterate the immense value of this book and the perseverance of both editors who managed to give life again to one of the most difcult Demotic text collections ever published.

14 It should be noted that although ten to twelve manuscripts are said to come from Dime, only B07 clearly presents the typical Roman Soknopaiu Nesos hand occurring also in documentary texts.

Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament: Introducing the Conceptual World of the Hebrew Bible. By John H. Walton. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2006. Pp. 368. $24.99. REVIEWED BY JOEL S. BADEn, Yale Divinity School. In this volume, J. Walton has gathered and synthesized material regarding what he refers to as the cognitive environment of the ancient Near East (ANE), focusing particularly on Mesopotamia and Egypt, in an attempt to elucidate the literature of ancient Israel through comparison with its neighboring cultures. Walton begins his study by laying out a very brief history of the origins of comparative study of the Hebrew Bible, turning quickly in the rst chapter to his own methodology. This is a clear, useful guide to the practice of comparative studies; especially helpfulto the beginning student as an introduction or to the advanced scholar as a reminderis his list of Principles of Comparative Study (pp. 2627). These serve as a guide for the rest of the work, and, for the most part, Walton follows his own principles admirably. Chapter 2 describes the challenges that comparative study presents to both critical and confessional scholarship. In the case of the former, Walton suggests that aspects of certain areas of critical scholarship are vulnerable to challenges by comparative data (although these areas are somewhat limited, at least as Walton presents them, and the challenges posed by the comparative data are as open to interpretation as the ideas being challenged). In the case of the latter, Walton does not dene precisely what he means by confessional scholarship, though he apparently is referring to any scholar with an acknowledged religious affiliation who also defends the authenticity or historicity of some or part of the biblical text. Even if Walton may have caricatured these scholars somewhat, his emphasis on the need for knowledge of the cognitive environment of ancient Israel for a more complete understanding of the biblical text is well taken. Chapter 3 is no more than a broad, yet brief, summary of the major texts from the ANE, with little description. Most useful, at least to a beginning student, is the (necessarily) abbreviated bibliographical information provided for each text. The majority of the book comprises a detailed study of various aspects of culture (including deities, temples, cosmology, historiography, kingship, and wisdom, among others), each of which is approached in essentially the same way. The body of the text is devoted to a discussion of the Egyptian and Mesopotamian views on each topic, and comparison with the view of the Hebrew Bible is given in sidebars entitled Comparative Exploration. Because Walton deals with so many major topics, and because this is but one volume, his treatment of the Egyptian and Mesopotamian material is of necessity somewhat broad throughout (although the major works in each eld are referred to in footnotes and in the bibliography). Perhaps more troubling is the attening of the Hebrew Bible (and the Egyptian and Mesopotamian material), such that Walton presents the perspective of the biblical text, to be compared with the ANE perspective(s). Although one cannot expect a volume of this limited size and scope to deal with the many variant traditions encompassed in the biblical

This content downloaded on Sun, 17 Mar 2013 16:41:26 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Thoth The Hermes of EgyptDocument232 pagesThoth The Hermes of Egyptjkelly1888100% (1)

- Tarot of Saqqara BookletDocument96 pagesTarot of Saqqara BookletLan Anh HàNo ratings yet

- Crowley-Harris Thoth (Major Arcana) PDFDocument7 pagesCrowley-Harris Thoth (Major Arcana) PDFcosmiNo ratings yet

- PDF - History of Egyptian Tarot DecksDocument4 pagesPDF - History of Egyptian Tarot DecksHysminaiNo ratings yet

- Components of A Research PaperDocument6 pagesComponents of A Research PaperMark Alvin Jay CarpioNo ratings yet

- The Omnipenetrating Ray of OkidanokhDocument19 pagesThe Omnipenetrating Ray of Okidanokhnikos nevrosNo ratings yet

- Evercoming Son in The Light of The Tarot - Frater Achad PDFDocument47 pagesEvercoming Son in The Light of The Tarot - Frater Achad PDFRicardo TakayamaNo ratings yet

- The Fall and Rise of Jerusalem Judah Und PDFDocument9 pagesThe Fall and Rise of Jerusalem Judah Und PDFrahmat fajarNo ratings yet

- (Roger Norman Whybray) Reading The Psalms As A BooDocument145 pages(Roger Norman Whybray) Reading The Psalms As A BooNestor Petruk100% (4)

- Viano, Cristina - Greco-Egyptian Alchemy PDFDocument15 pagesViano, Cristina - Greco-Egyptian Alchemy PDFAnonymous 8VbEv5tA3No ratings yet

- Räisänen-1980-The Portrait of Jesus in The QurDocument12 pagesRäisänen-1980-The Portrait of Jesus in The QurWes Dingman100% (1)

- The Story of The Shipwrecked SailorDocument124 pagesThe Story of The Shipwrecked SailorChristian Casey75% (4)

- The Story of The Shipwrecked SailorDocument124 pagesThe Story of The Shipwrecked SailorChristian Casey75% (4)

- (MARILYN B. SKINNER) Catullus in Verona ReadingDocument296 pages(MARILYN B. SKINNER) Catullus in Verona ReadingMarta DonnarummaNo ratings yet

- Deciphering The Codes in The Alphabetic OrdersDocument21 pagesDeciphering The Codes in The Alphabetic OrdersRichter, JoannesNo ratings yet

- Alchemical Brass - Part 2 - J.S BullockDocument6 pagesAlchemical Brass - Part 2 - J.S BullockbromleydaveNo ratings yet

- Vocal SunthemataDocument4 pagesVocal SunthemataPedro SegarraNo ratings yet

- GD Correspondence Course Lessons 022Document10 pagesGD Correspondence Course Lessons 022Welder OliveiraNo ratings yet

- HKT2 ColorScaleDocument36 pagesHKT2 ColorScaleAnonymous FmnWvIDj100% (1)

- Catharism and The TarotDocument28 pagesCatharism and The TarotSilver RatioNo ratings yet

- W. Wynn Westcott - Numbers, 1890Document64 pagesW. Wynn Westcott - Numbers, 1890mbox2100% (1)

- NumerologiaDocument27 pagesNumerologiaLuis PenhaNo ratings yet

- 15.the Color Spectrum ExerciseDocument7 pages15.the Color Spectrum ExerciseSumruhan GünerNo ratings yet

- Book of Wisdom: A Painting EntitledDocument49 pagesBook of Wisdom: A Painting EntitledMarc Raphael ParrikalNo ratings yet

- Notice of Runic Inscriptions Discovered During Recent Excavations in The Orkneys (1862)Document82 pagesNotice of Runic Inscriptions Discovered During Recent Excavations in The Orkneys (1862)Ber WeydeNo ratings yet

- Tarot Visconti-SforzaDocument2 pagesTarot Visconti-Sforzafederico100% (1)

- Liber 131 Vel IO PANDocument63 pagesLiber 131 Vel IO PANDanilo SenaNo ratings yet

- ManageriumDocument1 pageManageriumCaptain WalkerNo ratings yet

- Randolph Magia SexualisDocument17 pagesRandolph Magia Sexualis6rainbowNo ratings yet

- Historia Da DisbioseDocument11 pagesHistoria Da DisbioseNathalia GomesNo ratings yet

- Indian Philosophy A Critical SurveyDocument415 pagesIndian Philosophy A Critical SurveySivason100% (1)

- The Library of Esoterica 1 - Tarot (Jessica Hundley, Johannes Fiebig) (Z-Library)Document528 pagesThe Library of Esoterica 1 - Tarot (Jessica Hundley, Johannes Fiebig) (Z-Library)Monica Vera DuranNo ratings yet

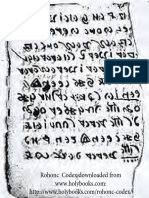

- Rohonc CodexDocument217 pagesRohonc CodexMartonNo ratings yet

- Janssen, J., Commodity Prices From The Ramessid. PeriodDocument312 pagesJanssen, J., Commodity Prices From The Ramessid. PeriodHesham Elshazly82% (17)

- Love Tarot Made Easy by Stella NerritDocument213 pagesLove Tarot Made Easy by Stella NerritAna DePetalosNo ratings yet

- Evidence: Noah's Ark Located? Noah Real or Myth? Noah's Ark Found?Document18 pagesEvidence: Noah's Ark Located? Noah Real or Myth? Noah's Ark Found?Zach Anderson100% (1)

- Student Copy of Beowulf Question Packet 2019 With LinesDocument15 pagesStudent Copy of Beowulf Question Packet 2019 With Linesapi-463193062No ratings yet

- Three Books OF Occult Philosophy: Henry Cornelius Agrippa of NettesheimDocument43 pagesThree Books OF Occult Philosophy: Henry Cornelius Agrippa of NettesheimJuan Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Mémoires of Paul Barras - Volume III - Pdf.crdownload - Pdf.crdownloadDocument700 pagesMémoires of Paul Barras - Volume III - Pdf.crdownload - Pdf.crdownloadKassandra M JournalistNo ratings yet

- Maier Atalanta FugiensDocument156 pagesMaier Atalanta Fugiensperkin_rodNo ratings yet

- Hassein's HandbookDocument123 pagesHassein's HandbookDiego LipovichNo ratings yet

- Tarot - Ramses (Eternity)Document3 pagesTarot - Ramses (Eternity)Luis Claudio PaivaNo ratings yet

- 1835 Kirckenhoffer The Oracle or Book of Fate PDFDocument109 pages1835 Kirckenhoffer The Oracle or Book of Fate PDFtim_rattanaNo ratings yet

- Paul Brunton - WikipediaDocument3 pagesPaul Brunton - WikipediaShabd_MysticNo ratings yet

- Tarot & Divination: Art of Lenormand Reading, The - Alexandre MusruckDocument2 pagesTarot & Divination: Art of Lenormand Reading, The - Alexandre MusruckAna PaulaNo ratings yet

- Vistas of Wisdom 60: Rituals: Imitating The PlanDocument2 pagesVistas of Wisdom 60: Rituals: Imitating The PlanRama KarthikNo ratings yet

- Hesiod Works and DaysDocument44 pagesHesiod Works and DaysNatalijaNo ratings yet

- Alternative NamesDocument17 pagesAlternative Namesav2422No ratings yet

- Kabbalah ArticleDocument5 pagesKabbalah ArticlepeddyppiNo ratings yet

- Ephesus Stands in JudgmentDocument6 pagesEphesus Stands in JudgmentUMA LUZ ALÉM DO MUNDONo ratings yet

- Aldebahran - Estudos de Astrologia Regentes Da Quarta Casa, Por Marion March & Joan McEversDocument18 pagesAldebahran - Estudos de Astrologia Regentes Da Quarta Casa, Por Marion March & Joan McEversalexandreNo ratings yet

- Sexuality Worksheet.307151540Document1 pageSexuality Worksheet.307151540Beto SecoNo ratings yet

- Planetary OrbitsDocument1 pagePlanetary OrbitsMaria Melusine100% (1)

- 999 La Gran FechaDocument2 pages999 La Gran Fechamazamo100% (1)

- Vaisakh LEODocument65 pagesVaisakh LEOjuan-angelNo ratings yet

- Vises de Descartes Portuguese Edition by Olavo de Carvalho B00k1ma78wDocument4 pagesVises de Descartes Portuguese Edition by Olavo de Carvalho B00k1ma78wLeandro CostaNo ratings yet

- Borges and The Kabbalah Pre-Texts To A TDocument8 pagesBorges and The Kabbalah Pre-Texts To A TMariaLuisaGirondoNo ratings yet

- Dante Alighieri and AutofictionDocument1 pageDante Alighieri and AutofictionLetícia AlcântaraNo ratings yet

- Reconciling Religion With ExtraterrestrialsDocument8 pagesReconciling Religion With ExtraterrestrialsDavid SaportasNo ratings yet

- Napoleons Oracle (Oraculum) SoftwareDocument1 pageNapoleons Oracle (Oraculum) Softwareall_right82405No ratings yet

- The Book of Thoth Etteilla PDF - Google SearchDocument2 pagesThe Book of Thoth Etteilla PDF - Google SearchPedro SallesNo ratings yet

- Appendix LamedDocument8 pagesAppendix LamedKiyo NathNo ratings yet

- Enochian Dictionary - Golden Dawn PDFDocument67 pagesEnochian Dictionary - Golden Dawn PDFFrateremenhetan100% (1)

- Hakdamat Sefer Hazohar (Introduction of TheDocument12 pagesHakdamat Sefer Hazohar (Introduction of TheAnnabel CorderoNo ratings yet

- VocabularyDocument2 pagesVocabularyLeoneteFernandesNo ratings yet

- AtlantisDocument1 pageAtlantisrandhir.sinha1592No ratings yet

- Area: Historical Interpretation of Archaeology. Historia Einzelschriften 121Document4 pagesArea: Historical Interpretation of Archaeology. Historia Einzelschriften 121megasthenis1No ratings yet

- Temple Library of Tebtynis: BibliographyDocument3 pagesTemple Library of Tebtynis: BibliographySemitic Kemetic ScientistNo ratings yet

- Laird - Handbook of Literary RhetoricDocument3 pagesLaird - Handbook of Literary Rhetorica1765No ratings yet

- PDFDocument23 pagesPDFMaria Antonietta RicciNo ratings yet

- Brochure CMU NLP 24-08-2022 V13Document13 pagesBrochure CMU NLP 24-08-2022 V13Maria Antonietta RicciNo ratings yet

- 2010 Fragment of A Funerary ShroudDocument10 pages2010 Fragment of A Funerary ShroudMaria Antonietta RicciNo ratings yet

- Anchist-Ahpg871 Unit Guide 2011-2Document11 pagesAnchist-Ahpg871 Unit Guide 2011-2Maria Antonietta RicciNo ratings yet

- Alpha WolfDocument5 pagesAlpha WolfmysticpaganNo ratings yet

- 41 Termination Fixed TermDocument1 page41 Termination Fixed TermMaria Antonietta RicciNo ratings yet

- 5 Ritual Form HypothesisDocument4 pages5 Ritual Form HypothesisMaria Antonietta RicciNo ratings yet

- Animal Behaviour: Udell Et Al. (2008) Wynne Et Al. (2008)Document6 pagesAnimal Behaviour: Udell Et Al. (2008) Wynne Et Al. (2008)Maria Antonietta RicciNo ratings yet

- BOLSHAKOV - The Moment of The Establishment of The Tomb-Cult in Ancient Egypt - AoF 18Document15 pagesBOLSHAKOV - The Moment of The Establishment of The Tomb-Cult in Ancient Egypt - AoF 18Maria Antonietta RicciNo ratings yet

- Animal Behaviour: Udell Et Al. (2008) Wynne Et Al. (2008)Document6 pagesAnimal Behaviour: Udell Et Al. (2008) Wynne Et Al. (2008)Maria Antonietta RicciNo ratings yet

- 5 Ritual Form HypothesisDocument4 pages5 Ritual Form HypothesisMaria Antonietta RicciNo ratings yet

- African Origin of The Ancient Egyptians PDFDocument13 pagesAfrican Origin of The Ancient Egyptians PDFMaria Antonietta RicciNo ratings yet

- 00 Contents EtcDocument13 pages00 Contents EtcMaria Antonietta RicciNo ratings yet

- HW R MCC 2005 New Fronters 01Document13 pagesHW R MCC 2005 New Fronters 01Maria Antonietta RicciNo ratings yet

- The Veldt DiscussionDocument3 pagesThe Veldt DiscussionAkshat jhaNo ratings yet

- Kobold Sorcerer Wild Magic 4Document3 pagesKobold Sorcerer Wild Magic 4llckatherisNo ratings yet

- Definition of ProsodyDocument5 pagesDefinition of ProsodyKholah RizwanNo ratings yet

- Tarikh e Masoodi (Mas'Udi) Tarjuma Muruj Al Zahab Wa Madin Al Jawahir Al Masoodi Jild-2 @Document429 pagesTarikh e Masoodi (Mas'Udi) Tarjuma Muruj Al Zahab Wa Madin Al Jawahir Al Masoodi Jild-2 @Faryal Yahya MemonNo ratings yet

- Poets of Medieval EraDocument4 pagesPoets of Medieval EraLaiba ShabbirNo ratings yet

- Cinderella School Tour Study Guide Synopsis FinalDocument1 pageCinderella School Tour Study Guide Synopsis Finalhester prynneNo ratings yet

- Xander and The Rainbow-Barfing Unicorns: Includes The Following TitlesDocument2 pagesXander and The Rainbow-Barfing Unicorns: Includes The Following Titlesjiyih53793No ratings yet

- Scheme of Work For Form 4 EnglishDocument12 pagesScheme of Work For Form 4 EnglishSafarinie SulaimanNo ratings yet

- Sastra and Our Acaryas FeaturesDocument1 pageSastra and Our Acaryas Featuresapi-26168166No ratings yet

- Unity in DualityDocument2 pagesUnity in DualityJenn KimNo ratings yet

- The Queen of AttoliaDocument11 pagesThe Queen of Attoliaapi-386086491No ratings yet

- 04 HBET4303 Course GuideDocument6 pages04 HBET4303 Course GuidezakiNo ratings yet

- Cbse Class 2 English Syllabus PDFDocument27 pagesCbse Class 2 English Syllabus PDFgomathiNo ratings yet

- LPW Criticism ExerciseDocument1 pageLPW Criticism ExerciseWrendell BrecioNo ratings yet

- Ех. 1. Put the foflowing into Indirect Speech. 1. (А)Document3 pagesЕх. 1. Put the foflowing into Indirect Speech. 1. (А)Marina AndreaduNo ratings yet

- Accounting Guideline Qualitative (Revision - Danelo)Document31 pagesAccounting Guideline Qualitative (Revision - Danelo)Zw RudiNo ratings yet

- DICTION: Word ChoiceDocument7 pagesDICTION: Word Choiceapi-234467265No ratings yet

- All LinksDocument238 pagesAll LinksMai_Manigandan_1292No ratings yet

- 07 - Chapter 1 PDFDocument29 pages07 - Chapter 1 PDFChuii MuiiNo ratings yet

- NarrativepdfDocument82 pagesNarrativepdfapi-267676063No ratings yet

- Mantra Push PamDocument2 pagesMantra Push PamnsiyamNo ratings yet

- Comparative Literature (Seminar 1,2) : (Sirens) Close ReadingDocument7 pagesComparative Literature (Seminar 1,2) : (Sirens) Close ReadingHelga OstaschenkoNo ratings yet

- A Study Into The Meaning of The Work GENTILE As Used in The Bible by Pastor Curtis Clair EwingDocument7 pagesA Study Into The Meaning of The Work GENTILE As Used in The Bible by Pastor Curtis Clair EwingbadhabitNo ratings yet