Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Functionalist Theory

Uploaded by

Fern HofileñaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Functionalist Theory

Uploaded by

Fern HofileñaCopyright:

Available Formats

FUNCTIONALIST THEORY

The functionalist perspective, also called functionalism, is one of the major theoretical perspectives in sociology. It has its origins in the works of Emile Durkheim, who was especially interested in how social order is possible or how society remains relatively stable. Functionalism interprets each part of society in terms of how it contributes to the stability of the whole society. Society is more than the sum of its parts; rather, each part of society is functional for the stability of the whole society. The different parts are primarily the institutions of society, each of which is organized to fill different needs and each of which has particular consequences for the form and shape of society. The parts all depend on each other. For example: the government, or state, provides education for the children of the family, which in turn pays taxes on which the state depends to keep itself running. The family is dependent upon the school to help children grow up to have good jobs so that they can raise and support their own families. In the process, the children become lawabiding, taxpaying citizens, who in turn support the state. If all goes well, the parts of society produce order, stability, and productivity. If all does not go well, the parts of society then must adapt to recapture a new order, stability, and productivity. Functionalism emphasizes the consensus and order that exist in society, focusing on social stability and shared public values. From this perspective, disorganization in the system, such as deviant behavior, leads to change because societal components must adjust to achieve stability. When one part of the system is not working or is dysfunctional, it affects all other parts and creates social problems, which leads to social change. The functionalist perspective achieved its greatest popularity among American sociologists in the 1940s and 1950s. While European functionalists originally focused on explaining the inner workings of social order, American functionalists focused on discovering the functions of human behavior. Among these American functionalist sociologists is Robert K. Merton, who divided human functions into two types: manifest functions, which are intentional and obvious and latent functions, which are unintentional and not obvious. The manifest function of attending a church or synagogue, for instance, is to worship as part of a religious community, but its latent function may be to help members learn to discern personal from institutional values. With common sense, manifest functions become easily apparent. Yet this is not necessarily the case for latent functions, which often demand a sociological approach to be revealed.

Functionalism has received criticism for neglecting the negative functions of an event such as divorce. Critics also claim that the perspective justifies the status quo and complacency on the part of society's members. Functionalism does not encourage people to take an active role in changing their social environment, even when such change may benefit them. Instead, functionalism sees active social change as undesirable because the various parts of society will compensate naturally for any problems that may arise

Functionalism: Basic Principles...

1. It is useful to employ an organism analogy to an understanding of the Functionalist Perspective.

Societies are analogous to living organisms (for example, a human being). Each part of the human body is linked, in some way, to all other parts. Individual organs combine to create something that is "greater than the sum total of their individual parts". In social terms, "organs" equate to social institutions (patterns of shared, stable, behavior) and the focus of analysis is upon the relationship between various institutions in society. This represents a macro approach to the theorizing and study of the social world.

2. All parts of a society have: a. A purpose (or function). b. Certain needs.

For example, the purpose of the work institution is to create wealth and in order to do this it needs people with a certain level of educational knowledge.

In this respect, each institution in society faces certain problems that have to be solved if it is to both exist and function properly. TAlcott Parsons identifies these as: a. Goal Attainment

This involves the need to set goals for human behavior and also to determine the means through which they can be achieved (the means of keeping an institution moving towards its allotted goals). b. Adaptation This involves procuring the means to achieve valued goals. this may, for example, involve the ability to create / provide the physical necessities of institutional life. c. Integration People have to be made to feel a part of any institution. They need to be made to feel that they belong and one way of achieving this is to give them something that they can hold in common (values, beliefs, etc.). The ability of an institution to integrate people successfully is vital for its continuation, internal harmony and so forth. d. Latency (or Pattern Maintenance) This involves the development of social control mechanisms that serve to manage tensions, motivate people, resolve interpersonal conflicts and the like within an institution. Parsons calls the above functional imperatives". That is, "structural commands" that have to be met if an institution - or indeed a society - is to continue to exist. 3. The above leads to the concept of functional interdependence between institutions in society. The purpose of each institution can only be properly understood by examining the relationship it has to all other institutions in society. 4. Society is seen as a form of living organism that exists independently of individuals. Society exists "out there" in the structure of people's social relationships rather than "in here" (inside the mind of individual social actors). 5. People experience society in terms of structural pressures and constraints on their behavior (for example, the pressure to go to school or to work, the pressure to form a family and have children and so forth). In this respect, society is like a "hidden hand" that pushes and coerces people in their daily lives - making us do things that we may not particularly want to do but which we have to do if we are to survive or to continue with our responsibilities to other people. This concept was originally used by Adam Smith ("The Wealth of Nations") to explain the way in which economic markets work. The relationships into which we enter place rules, routines and responsibilities on us and our recognition of these things acts like a hidden hand controlling our behavior. 6. "Individual choice" is not a useful concept for Functionalists because people are seen to react to social stimulation (pressure). That is, they respond to various structural pressures and we learn our responses through the socialization process. 7. Social order is based upon and maintained by a value consensus - a basic agreement about values. These basic values derive from the "functional imperatives" noted above (generated by the way in which institutions have purpose and needs).

8. Durkheim ("The Rules of Sociological Method", 1895) emphasizes two concepts: a. Social Solidarity - the feeling that we belong to a common society (that we have certain basic values in common with people). Solidarity is based upon such things as common culture, socialization, basic values and norms, etc. b. Collective Conscience - the "external expression" of the collective will of people living in a society. This represents the social forces that help bind people together (to integrate them into the collective behavior that is society). It can be likened to the "will" of society. 9. In methodological terms, Functionalism has historical links to positivism, although Durkheim refers to realist methodological concepts (unobservable phenomena such as "levels of social integration" in relation to suicide). If people's behavior is a response to social stimulation, this is like the natural world (where objects react in a nonconscious way to external forces - a light bulb cannot decide not to shine, for example). Therefore, it is possible to study human beings in much the same way since their "consciousness" is not a significant variable in the overall scientific equation. Thus it is possible to study the social world: a. Objectively (that is, with out reference to the sociologist's personal values) and b. Scientifically (that is, in terms of social facts rather than opinions). Functionalist sociology, therefore, tends to advocate the concept of value-freedom in relation to the study of social life.

Functional Requisites are basic functions that must be carried out for societies to survive and thrive.

n sociological research, functional prerequisites are the basic needs (food, shelter, clothing, and money) that an [1] individual requires to live above the poverty line. Functional prerequisites may also refer to the factors that allow a society to maintain social order. Herbert Blumer (1969), who coined the term "symbolic interactions," set out three basic premises of the perspective:

"Humans act toward things on the basis of the meanings they ascribe to those things." "The meaning of such things is derived from, or arises out of, the social interaction that one has with others and the society." "These meanings are handled in, and modified through, an interpretative process used by the person in dealing with the things he/she encounters."

COMPONENTS PARTS OF A SOCIAL STRUCTURE

Culture, groups, social class, social status, social roles, and stigmas.

Forms of relation and interaction

Forms of relation and interaction in sociology and anthropology may be described as follows: first and most basic are animal-like behaviors, i.e. various physical movements of the body. Then there are actions - movements with a meaning and purpose. Then there are social behaviors, orsocial actions, which address (directly or indirectly) other

people, which solicit a response from another agent. Next are social contacts, a pair of social actions, which form the beginning of social interactions. Social interactions in turn form the basis of social relations. Symbols define social relationships. Without symbols, our social life would be no more sophisticated than that of animals. For example, without symbols we would have no aunts or uncles, employers or teachers-or even brothers and sisters. In sum, Symbolic integrationists analyze how social life depends on the ways we define ourselves and others. They study face-to-face interaction, examining how people make sense out of life, how they determine their relationships

PRINCIPLES OF CLASSICAL CONDITIONING

Behaviorists have described a number of different phenomena associated with classical conditioning. Some of these elements involve the initial establishment of the response, while others describe the disappearance of a response. These elements are important in understanding the classical conditioning process.

Acquisition

is the initial stage of learning when a response is first established and gradually strengthened. For example, imagine that you are conditioning a dog to salivate in response to the sound of a bell. You repeatedly pair the presentation of food with the sound of the bell. You can say the response has been acquired as soon as the dog begins to salivate in response to the bell tone. Once the response has been acquired, you can gradually reinforce the salivation response to make sure the behavior is well learned.

Extinction

is when the occurrences of a conditioned response decrease or disappear. In classical conditioning, this happens when a conditioned stimulus is no longer paired with an unconditioned stimulus. For example, if the smell of food (the unconditioned stimulus) had been paired with the sound of a whistle (the conditioned stimulus), it would eventually come to evoke the conditioned response of hunger. However, if the unconditioned stimulus (the smell of food) were no longer paired with the conditioned stimulus (the whistle), eventually the conditioned response (hunger) would disappear.

Spontaneous Recovery

Is the reappearance of the conditioned response after a rest period or period of lessened response. If the conditioned stimulus and unconditioned stimulus are no longer associated, extinction will occur very rapidly after a spontaneous recovery.

Stimulus Generalizations the tendency for the conditioned stimulus to evoke similar responses after the response has been conditioned. For example, if a child has been conditioned to fear a stuffed white rabbit, the child will exhibit fear of objects similar to the conditioned stimulus.

Discrimination Is the ability to differentiate between a conditioned stimulus and other stimuli that have not been paired with an unconditioned stimulus. For example, if a bell tone were the conditioned stimulus, discrimination would involve being able to tell the difference between the bell tone and other similar sounds.

You might also like

- What Is The Functionalist Perspective in Sociology?Document3 pagesWhat Is The Functionalist Perspective in Sociology?Charls Gevera100% (2)

- 3 Major Theories of Sociology - SONNYDocument12 pages3 Major Theories of Sociology - SONNYSonny Boy SajoniaNo ratings yet

- What Is Structural FunctionalismDocument11 pagesWhat Is Structural FunctionalismYvane RoseNo ratings yet

- Structural FunctionalismDocument4 pagesStructural Functionalismangely joy arabisNo ratings yet

- Structural Functional TheoryDocument11 pagesStructural Functional TheoryMadelyn Rebamba100% (4)

- Structural FunctionalismDocument23 pagesStructural FunctionalismjogiedejesusNo ratings yet

- Importance of Social InstitutionDocument3 pagesImportance of Social InstitutionLander Dean AlcoranoNo ratings yet

- Social Change: and Its TheoriesDocument14 pagesSocial Change: and Its Theoriesshaira alliah de castroNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Profed 2Document9 pagesChapter 3 Profed 2Maximus YvosNo ratings yet

- Marxist Conflict TheoryDocument8 pagesMarxist Conflict TheoryRolip Saptamaji100% (1)

- Goode and HattDocument10 pagesGoode and Hattneetiprakash88% (8)

- Social DisorganizationDocument7 pagesSocial DisorganizationSyed Hassan100% (3)

- Social InstitutionDocument5 pagesSocial InstitutionYayati Jadhav100% (2)

- Inside Out Movie Reflection and EmotionsDocument2 pagesInside Out Movie Reflection and EmotionsAuroraNo ratings yet

- Cultural and Social Change TheoriesDocument16 pagesCultural and Social Change Theoriesjen211111100% (2)

- Marxist Perspective On EducationDocument15 pagesMarxist Perspective On EducationMel BoochoonNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Education and Society 2Document4 pagesRelationship Between Education and Society 2CHIRANJIBI BEHERANo ratings yet

- Origin of SociologyDocument3 pagesOrigin of SociologyKouch Rithy75% (4)

- Structural Functionalist Theory: Hbse 5 - Group 1Document37 pagesStructural Functionalist Theory: Hbse 5 - Group 1Jayson Tibayan67% (3)

- AGIL ParadigmDocument3 pagesAGIL ParadigmNofilia Citra Candra83% (6)

- Social ChangeDocument15 pagesSocial ChangeViconus Biz Trading Company Ltd VBTCL50% (2)

- Social StratificationDocument20 pagesSocial StratificationMayank Aameria0% (1)

- Social StratificationDocument4 pagesSocial StratificationBabar Khan64% (14)

- Social Stratification Types, Characteristics and ExamplesDocument6 pagesSocial Stratification Types, Characteristics and ExamplesAshfaq KhanNo ratings yet

- Social LifeDocument46 pagesSocial Lifegrace pinontoanNo ratings yet

- Interactionists TheoryDocument33 pagesInteractionists TheoryJelyne santosNo ratings yet

- Marxist TheoryDocument31 pagesMarxist Theoryllefela2000100% (4)

- Contribution of Karl Marx Sociology: 1 SemesterDocument18 pagesContribution of Karl Marx Sociology: 1 SemesterGulshan Singh100% (1)

- Subfields of Political ScienceDocument2 pagesSubfields of Political ScienceAyan BalochNo ratings yet

- Relationship of Sociology and Other Social Science DisciplinesDocument15 pagesRelationship of Sociology and Other Social Science DisciplinesUthpala Isi80% (5)

- Structural Functionalism EssayDocument2 pagesStructural Functionalism EssayJehannah Dayanara Berdan HayudiniNo ratings yet

- Structural FunctionalismDocument12 pagesStructural FunctionalismNicqueNadineNo ratings yet

- Conflict Vs Consensus TheoryDocument4 pagesConflict Vs Consensus TheoryJOHN LOUIE FLORES100% (1)

- Forms of Categorical SyllogismDocument5 pagesForms of Categorical SyllogismKatharina CantaNo ratings yet

- Structural Functional TheoryDocument7 pagesStructural Functional TheoryRchester CorpuzNo ratings yet

- Social StratificationDocument5 pagesSocial StratificationdrarpitabasakNo ratings yet

- FunctionalismDocument17 pagesFunctionalismRam ChapagainNo ratings yet

- Herbert Spencer's Theory of Social EvolutionDocument12 pagesHerbert Spencer's Theory of Social Evolutionrmbj94_scribd100% (1)

- Theories of Social StratificationDocument6 pagesTheories of Social StratificationShailjaNo ratings yet

- Durkheim's Theory of Suicide and TypesDocument17 pagesDurkheim's Theory of Suicide and TypesAnantHimanshuEkka100% (1)

- Social InteractionDocument15 pagesSocial InteractionparamitaNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Sociology: The Scientific Study of Social BehaviorDocument35 pagesIntroduction to Sociology: The Scientific Study of Social BehaviorJannat RajputNo ratings yet

- Social Interaction & StructureDocument17 pagesSocial Interaction & StructurePiyush AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Socialization 2Document8 pagesSocialization 2Ghulam FatimaNo ratings yet

- Marxist CriticismDocument5 pagesMarxist Criticismsyeda saira batool100% (1)

- Social StratificationDocument7 pagesSocial StratificationatreNo ratings yet

- Conflict Theory: An Analysis of Karl Marx's Social Conflict TheoryDocument18 pagesConflict Theory: An Analysis of Karl Marx's Social Conflict TheoryZetroc JessNo ratings yet

- Classical Theories of Social StratificationDocument12 pagesClassical Theories of Social StratificationkathirNo ratings yet

- Wid Wad Gad Lec3Document14 pagesWid Wad Gad Lec3Biswajit Darbar100% (2)

- 06 Chapter 1Document30 pages06 Chapter 1EjazSulemanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2-Weberian BureaucracyDocument16 pagesChapter 2-Weberian BureaucracyIra Nazirah100% (1)

- Social StructureDocument2 pagesSocial Structurefatima100% (1)

- Authoritarian GovernmentDocument11 pagesAuthoritarian GovernmentAnn SaNo ratings yet

- Social Action ConceptDocument13 pagesSocial Action ConceptMonis Qamar100% (4)

- Socialization in Formal and Informal OrganizationDocument8 pagesSocialization in Formal and Informal OrganizationDr. Nisanth.P.M100% (4)

- Lecture No. 6 (Social and Cultural Change) PDFDocument29 pagesLecture No. 6 (Social and Cultural Change) PDFMuhammad WaseemNo ratings yet

- Structural Functionalism Theory ExplainedDocument13 pagesStructural Functionalism Theory ExplainedEwa EraNo ratings yet

- Functionalism in SociologyDocument8 pagesFunctionalism in Sociologynad101No ratings yet

- Structural FunctionalismDocument33 pagesStructural Functionalismdado.136546120986No ratings yet

- Social Thought and Sociological TheoryDocument8 pagesSocial Thought and Sociological TheoryBushra Ali100% (4)

- Trends worksheet answersDocument3 pagesTrends worksheet answersFern HofileñaNo ratings yet

- Chemical BondingDocument45 pagesChemical BondingFern HofileñaNo ratings yet

- Chem Bondunit 03 Answers To HomeworkDocument8 pagesChem Bondunit 03 Answers To HomeworkFern HofileñaNo ratings yet

- D 243437Document4 pagesD 243437Fern HofileñaNo ratings yet

- Hkey 02 PttrendsDocument1 pageHkey 02 PttrendsFern HofileñaNo ratings yet

- How BeautifulDocument3 pagesHow BeautifulFern HofileñaNo ratings yet

- Periodic TrendsDocument11 pagesPeriodic TrendsFern HofileñaNo ratings yet

- SCH 3UI Unit 3 Outline: Chemical BondingDocument7 pagesSCH 3UI Unit 3 Outline: Chemical BondingFern HofileñaNo ratings yet

- Tos FormatDocument2 pagesTos FormatFern HofileñaNo ratings yet

- Trends in PTDocument2 pagesTrends in PTFern HofileñaNo ratings yet

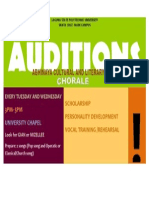

- AuditionsDocument1 pageAuditionsFern HofileñaNo ratings yet

- Campus Ministry Choir Audition FormDocument1 pageCampus Ministry Choir Audition FormFern HofileñaNo ratings yet

- Ionic and Covalent BondsDocument5 pagesIonic and Covalent BondsFern HofileñaNo ratings yet

- During An Episode of Acute BronchitisDocument1 pageDuring An Episode of Acute BronchitisFern HofileñaNo ratings yet

- CM Program of Activities 2013-2014Document4 pagesCM Program of Activities 2013-2014Fern HofileñaNo ratings yet

- MIB0612 - Thesis - Violetta - Bankovskaya - Development of Conflict Management Strategies To Increase The Organizational Effectiveness in Nordic Companies PDFDocument109 pagesMIB0612 - Thesis - Violetta - Bankovskaya - Development of Conflict Management Strategies To Increase The Organizational Effectiveness in Nordic Companies PDFmesfin DemiseNo ratings yet

- Contemp Social ProblemsDocument542 pagesContemp Social ProblemsCristina Serban100% (1)

- Background To SociologyDocument47 pagesBackground To SociologyFarah NoreenNo ratings yet

- Social Science Disciplines and Approaches in the Social SciencesDocument2 pagesSocial Science Disciplines and Approaches in the Social SciencesMichelle Berme90% (21)

- Feudal Japan sword testing ritual analysisDocument12 pagesFeudal Japan sword testing ritual analysisXavi TeixidóNo ratings yet

- ASAD, Talal. Medieval Heresy.Document19 pagesASAD, Talal. Medieval Heresy.Odir FontouraNo ratings yet

- Social Functions of Emotions at Four LevelsDocument17 pagesSocial Functions of Emotions at Four LevelsGabriel MedinaNo ratings yet

- Ebook PDF Think Sociology Second 2nd Canadian Edition by John D Carl PDFDocument41 pagesEbook PDF Think Sociology Second 2nd Canadian Edition by John D Carl PDFgeorge.dixon339100% (28)

- Classification of Social Work TheoriesDocument31 pagesClassification of Social Work TheoriesMaitreyi SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Original PDF Sociology Compass For A New Social World 6th PDFDocument41 pagesOriginal PDF Sociology Compass For A New Social World 6th PDFalyssa.meiners162100% (32)

- Bourdieu 1979 Symbolic PowerDocument5 pagesBourdieu 1979 Symbolic PowerAnneThraxNo ratings yet

- Social Problems A Down To Earth Approach 12th Edition Henslin Solutions Manual DownloadDocument13 pagesSocial Problems A Down To Earth Approach 12th Edition Henslin Solutions Manual DownloadAlbert Garrett100% (20)

- ELSA-Introduction To CriminologyDocument160 pagesELSA-Introduction To CriminologyPaul SmithNo ratings yet

- Women's Studies IntroDocument108 pagesWomen's Studies IntroBrenda HangNo ratings yet

- David Mitrany and FunctionalismDocument11 pagesDavid Mitrany and FunctionalismNoman_Shabbir_494No ratings yet

- Jack Goody The Character of KinshipDocument264 pagesJack Goody The Character of KinshipJimena Massa100% (2)

- LET REVIEWER Social Dimensions of EducationDocument11 pagesLET REVIEWER Social Dimensions of EducationKing Nehpets Alcz60% (5)

- Gender and FamiliesDocument24 pagesGender and FamiliesQuintowas Jr RazumanNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: Sociology 9699/22 March 2021Document16 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: Sociology 9699/22 March 2021Tamer AhmedNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Sociology A Brief Introduction 9th Edition by SchaeferDocument17 pagesTest Bank For Sociology A Brief Introduction 9th Edition by Schaefermarissafowlertdpsbecagz100% (17)

- Test Bank For Sociology A Down To Earth Approach 11th Edition James M HenslinDocument24 pagesTest Bank For Sociology A Down To Earth Approach 11th Edition James M HenslinMohammad Brazier100% (25)

- Is Teaching A ProfessionDocument18 pagesIs Teaching A ProfessionKyleruwlz FizrdNo ratings yet

- 9699 Sociology: MARK SCHEME For The October/November 2014 SeriesDocument8 pages9699 Sociology: MARK SCHEME For The October/November 2014 Seriesdenidenis1235No ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document64 pagesChapter 1Zacky WanNo ratings yet

- Profiles and Critiques in Social TheoryDocument249 pagesProfiles and Critiques in Social TheoryAna Maria B100% (1)

- Lesson 3 Social Science Theories and Their Implications To EducationDocument4 pagesLesson 3 Social Science Theories and Their Implications To EducationAremzyNo ratings yet

- Edited - Sociology-2013 #4Document3 pagesEdited - Sociology-2013 #4renell simonNo ratings yet

- Whealey 1969 City As SymbolDocument16 pagesWhealey 1969 City As SymbolLorena TrambitasNo ratings yet

- Aston, What Is Structure and Agency - How Does This Framework Help Us in Political Analysis - Approaches To Political AnalysisDocument10 pagesAston, What Is Structure and Agency - How Does This Framework Help Us in Political Analysis - Approaches To Political AnalysishoorieNo ratings yet

- Topic Group Present (Week 8) Chapter 1:sociology and Learning ManagementDocument2 pagesTopic Group Present (Week 8) Chapter 1:sociology and Learning ManagementLEE LEE LAUNo ratings yet