Professional Documents

Culture Documents

2011 MLJ 721 PDF

Uploaded by

DIN08Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

2011 MLJ 721 PDF

Uploaded by

DIN08Copyright:

Available Formats

[2011] 1 MLJ

Chong Fook Sin v Amanah Raya Bhd (as the administrator for the estate of Raja Nong Chik bin Raja Ishak, deceased) & Ors (Alauddin PCA)

721

Chong Fook Sin v Amanah Raya Bhd (as the administrator for the estate of Raja Nong Chik bin Raja Ishak, deceased) & Ors

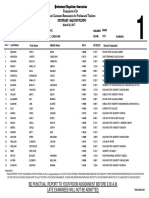

FEDERAL COURT (PUTRAJAYA) CIVIL APPEAL NO 02()37 OF 2009(W) ALAUDDIN PCA, RAUS SHARIF AND HELILIAH FCJJ 19 JULY 2010 Civil Procedure Intervention Application for Intervener application at appellate stage Intervention by beneciaries of estate into proceedings brought by administrator of estate Whether High Court test for intervention applicable Whether Court of Appeal correctly determined intervener application Rules of the High Court 1980 O 15 r 6(2)(b) Rules of the Court of Appeal 1994 r 4 Succession Administration Application to intervene by beneciaries of estate into proceedings brought by administrator of estate Whether benecial interest to estate accrued Whether beneciaries had legal interest in subject of appeal Whether issue estoppel and res judicata prevented interveners from seeking leave to intervene Amanah Raya Bhd (ARB) the rst respondent in Civil Appeal No 02()37 of 2009(W) was at all material times the administrator of the estate of Raja Datuk Nong Chik bin Raja Ishak (the deceased). The second to sixth respondents, who were at all material times the beneciaries to the estate of the deceased, had instituted legal proceedings against 13 defendants in respect of an alleged conspiracy to defraud the estate of the deceased. However, this claim was struck out by the High Court on 9 March 1998. Thereafter in August 1998, ARB as the administrator of the estate of the deceased had commenced legal proceedings, on behalf of the second to sixth respondents, against the said 13 defendants. This claim proceeded to case management on more than ten occasions and on 7 April 2004, ARBs solicitors application to discharge themselves was allowed. However, an application for a further adjournment was denied and since ARB conceded that it was not ready to proceed with the trial at that point its claim was struck out. On 28 April 2004, ARB appealed to the Court of Appeal against that decision to strike out its claim. On 12 November 2008, the second to sixth respondents led an intervener application to intervene into the civil appeal. The second to sixth respondents (the interveners) submitted that the basis of the intervener application was to ensure that all matters were effectively and completely determined and adjudicated upon and to lend all necessary assistance. Cheong Fook Sin, the appellant, opposed the intervener application on, inter alia, the grounds that the interveners did not have any basis in fact and/or law to intervene as they did

722

Malayan Law Journal

[2011] 1 MLJ

not have any legal interest in the subject of the appeal. It was the appellants contention that the interveners as beneciaries of the estate of the deceased did not have an interest in the said estate until administration was complete and distribution made. The appellant also averred that the interveners right to commence an action had been put to rest when their initial attempt to institute an action was struck out and that since they did not appeal against that decision they were tied down by issue estoppel from intervening in the instant appeal. The appellant further cited inordinate delay by the interveners. The Court of Appeal found that the interveners had a benecial interest which was sufcient for present purposes and that the said benecial interest directly related to the subject matter of the appeal. The Court of Appeal also held that O 15 r 6(2)(b) of the Rules of the High Court 1980 (RHC) applied by reason of a lacuna in the Rules of the Court of Appeal 1994 (RCA). This was the appellants appeal against that decision for which leave was granted on 12 October 2009. All the parties agreed that the result of this appeal would bind two other appeals arising from these facts. It was the appellants contention that the interveners had no legal basis to intervene into the proceedings and that the Court of Appeal had erred in law and/or fact in failing to appreciate that the test for intervention into appellate proceedings is the same as that for intervention into the High Court proceedings. Held, allowing the appeal with costs here and below: (1) The law in respect of evaluating intervener applications is found in O 15 r 6(2)(b) of the RHC. The RCA is silent as to intervener applications and there is no provision which is in pari materia to O 15 r 6(2)(b) of the RHC. However, r 4 of the RCA allows the procedure and practice in the RHC 1980 to apply mutatis mutandis where no other provision is made by any written law or by these Rules. As such the Court of Appeal does have the jurisdiction or power to determine an intervener application under O 15 r 6(2)(b) of the RHC read together r 4 of the RCA. The test of legal interest would still be applicable but the legal interest in issue must be an interest in the subject matter of the appeal before the Court of Appeal. However, in the present appeal the subject matter of the appeal to the Court of Appeal was separate and distinct from the subject matter of the proceedings at the High Court. The interveners asserted an interest by reason of being beneciaries of the estate of the deceased and this was more relevant to the proceedings in the High Court prior to the claim being struck off. The appeal only concerned ARBs non-compliance with the unless order made against it and this did not involve the interveners qua beneciaries. An indirect interest could not amount to a legal interest. Further, the interveners basis for making the intervener application which was to lend assistance did not establish a legal interest (see paras 2634, 39(a)(c)).

[2011] 1 MLJ

Chong Fook Sin v Amanah Raya Bhd (as the administrator for the estate of Raja Nong Chik bin Raja Ishak, deceased) & Ors (Alauddin PCA)

723

(2) The interveners did not seek to intervene at the rst available opportunity and no explanation was made by them as to the reasons for not making an application in the High Court. Apart from the legal interest, an applicant must establish that he was not precluded by any other circumstances from making such an application. Such precluding circumstances would include a prior determination of the courts that gave rise to an issue estoppel. There was such a determination of the capacity and interest of the interveners to bring a suit and as such an issue estoppel arose and the interveners were bound by the doctrine of res judicata (see paras 3638, 39(e)(i)). (3) The Court of Appeal had erred in allowing the intervener application (see para 39). [Bahasa Malaysia summary

Amanah Raya Bhd (ARB), responden pertama di dalam Rayuan Sivil No 02()-37 Tahun 2009(W), pada kesemua masa material adalah pentadbir harta pusaka Raja Datuk Nong Chin bin Raja Ishak (si mati). Responden kedua hingga keenam, yang pada kesemua masa material benesiari harta pusaka si mati telah memulakan prosiding undang-undang terhadap kesemua 13 defendan berkaitan dakwaan komplot untuk menipu harta pusaka si mati. Walau bagaimanapun, tuntutan ini dibatalkan oleh Mahkamah Tinggi pada 9 Mac 1998. Kemudiannya pada Ogos 1998, ARB sebagai pentadbir harta pusaka si mati telah memulakan prosiding undang-undang, bagi pihak responden-responden kedua hingga keenam, terhadap kesemua 13 defendan tersebut. Tuntutan ini diteruskan ke pengurusan kes lebih daripada sepuluh kali dan pada 7 April 2004, permohonan peguam ARB untuk melepaskan mereka dibenarkan. Walau bagaimanapun, permohonan untuk penangguhan selanjutnya dinakan dan memandangkan ARB bersetuju bahawa ia tidak bersedia untuk meneruskan dengan perbicaraan pada ketika itu, tuntutannya dibatalkan. Pada 28 April 2004, ARB merayu kepada Mahkamah Rayuan terhadap keputusan untuk membatalkan tuntutannya. Pada 12 November 2008, responden-responden kedua hingga keenam memfailkan permohonan mencelah untuk mencelah dalam rayuan sivil tersebut. Responden-responden kedua hingga keenam (pencelah-pencelah) berhujah bahawa dasar permohonan mencelah adalah untuk memastikan kesemua perkara secara efektif dan ditentukan sepenuhnya dan dihakimi dan untuk memberikan kesemua bantuan yang perlu. Perayu menentang permohonan mencelah tersebut, antara lain, atas alasan bahawa pencelah-pencelah tidak mempunyai asas dalam fakta dan/atau undang-undang untuk mencelah kerana mereka tidak mempunyai apa-apa kepentingan undang-undang di dalam perkara rayuan tersebut. Adalah hujahan perayu bahawa pencelah-pencelah sebagai benesiari-benesiari harta pusaka si mati tidak mempunyai kepentingan di dalam harta pusaka sehingga pentadbiran telah selesai dan pembahagian dibuat. Perayu juga menghujah bahawa hak pencelah untuk memulakan

724

Malayan Law Journal

[2011] 1 MLJ

tindakan telah dihalang apabila percubaan permulaan mereka untuk memulakan tindakan dibatalkan dan memandangkan mereka tidak merayu terhadap keputusan tersebut mereka dihalang oleh isu estopel daripada mencelah di dalam rayuan ini. Perayu selanjutnya merujuk kelewatan melampau oleh pencelah-pencelah. Mahkamah Rayuan mendapati bahawa pencelah-pencelah mempunyai kepentingan benesiari yang mana mencukupi untuk tujuan ini dan bahawa kepentingan benesiari tersebut berkait terus kepada perkara subjek rayuan tersebut. Mahkamah Rayuan juga memutuskan bahawa A 15 k 6(2)(b) Kaedah-Kaedah Mahkamah Tinggi 1980 (KMT) dipohon atas sebab lakuna di dalam Kaedah-Kaedah Mahkamah Rayuan 1994 (KMR). Ini adalah rayuan perayu terhadap keputusan yang mana keizinan diberi pada 12 Oktober 2009. Kesemua pihak bersetuju bahawa keputusan rayuan akan mengikat kedua-dua rayuan berbangkit daripada fakta ini. Ia adalah hujahan perayu bahawa pencelah-pencelah tidak mempunyai asas undang-undang untuk campur tangan dalam prosiding dan bahawa Mahkamah Rayuan terkhilaf dalam undang-undang dan/atau fakta dalam gagal untuk meneliti bahawa ujian untuk campur tangan dalam prosiding mahkamah rayuan adalah sama dengan campur tangan prosiding Mahkamah Tinggi. Diputuskan, membenarkan rayuan dengan kos di mahkamah ini dan Mahkamah Rayuan: (1) Undang-undang berkaitan penilaian permohonan-permohonan mencelah didapati di dalam A 15 k 6(2)(b) KMT. KMR tidak menyatakan apa-apa mengenai permohonan-permohonan mencelah dan tidak terdapat peruntukan yang mana adalah pari materia dengan A 15 k 6(2)(b) KMT. Walau bagaimanapun k 4 KMR membenarkan prosedur dan amalan di dalam KMT untuk menggunapakai mutatis mutandis where no other provision is made by any written law or by these Rules. Oleh itu Mahkamah Rayuan sememangnya mempunyai bidang kuasa atau kuasa untuk menentukan permohonan mencelah di bawah A 15 k 6(2)(b) KMT dibaca bersama k 4 KMR. Ujian legal interest akan masih beraplikasi tetapi kepentingan undang-undang dalam isu mestilah kepentingan di dalam perkara subjek rayuan di hadapan Mahkamah Rayuan. Walau bagaimanapun, dalam rayuan ini perkara subjek rayuan kepada Mahkamah Rayuan adalah berasingan dan berlainan daripada perkara subjek prosiding di Mahkamah Tinggi. Pencelah-pencelah menegaskan kepentingan atas alasan sebagai benesiari-benesiari harta pusaka si mati dan ini adalah lebih relevan kepada prosiding di Mahkamah Tinggi sebelum tuntutan tersebut dibatalkan. Rayuan hanya berkaitan ketidakpatuhan oleh ARB terhadap perintah terlebih dahulu yang dibuat terhadapnya dan ini tidak melibatkan pencelah-pencelah qua benesiari-benesiari. Kepentingan tak langsung tidak terjumlah kepada kepentingan undang-undang.

[2011] 1 MLJ

Chong Fook Sin v Amanah Raya Bhd (as the administrator for the estate of Raja Nong Chik bin Raja Ishak, deceased) & Ors (Alauddin PCA)

725

Selanjutnya, asas pencelah-pencelah membuat permohonan mencelah yang mana adalah untuk memberi bantuan tidak membuktikan legal interest (lihat perenggan 2634, 39(a)(c)). (2) Pencelah-pencelah tidak memohon untuk mencelah pada peluang pertama yang wujud dan tiada penjelasan dibuat oleh mereka terhadap alasan-alasan untuk tidak membuat permohonan di Mahkamah Tinggi. Selain daripada kepentingan undang-undang, pemohon mesti membuktikan bahawa dia tidak dihalang oleh apa-apa keadaan lain daripada membuat permohonan sedemikian. Keadaan menghalang sedemikian akan melibatkan penentuan mahkamah sebelumnya yang membangkitkan kepada isu estopel. Terdapat penentuan kapasiti sedemikian dan kepentingan pencelah-pencelah untuk mengambil tindakan dan oleh itu isu estopel berbangkit dan pencelah-pencelah terikat kepada doktrin res judicata (lihat perenggan 3638, 39(e)(i)). (3) Mahkamah Rayuan tersilap dalam membenarkan permohonan mencelah tersebut (lihat perenggan 39).] Notes For cases on administration of succession in general, see 11 Mallals Digest (4th Ed, 2008 Reissue) paras 20062088. For cases on application for intervention, see 2 Mallals Digest (4th Ed, 2010 Reissue) paras 40894091. Cases referred to Chor Phaik Har v Farlim Properties Sdn Bhd [1997] 3 MLJ 188; [1997] 4 CLJ 393, FC (refd) Fairview Schools Bhd v Indrani a/p Rajaratnam & Ors (No 1) [1998] 1 MLJ 99; [1998] 1 CLJ 285, CA (refd) Hong Leong Bank Bhd (formerly known as Hong Leong Finance Bhd) v Staghorn Sdn Bhd and other appeals [2008] 2 MLJ 622; [2008] 2 CLJ 121, FC (refd) Law Hock Key & Anor v Yap Meng Kan & Ors [2008] 3 CLJ 470, CA (refd) Pegang Mining Co Ltd v Choong Sam & Ors [1969] 2 MLJ 52, PC (folld) Tohtonku Sdn Bhd v Superace (M) Sdn Bhd [1992] 2 MLJ 63; [1992] 2 CLJ 1153; [1992] 1 CLJ 344 (Rep), SC (folld) Tradium Sdn Bhd v Zain Azahari bin Zainal Abidin & Anor [1995] 1 MLJ 668; [1996] 2 CLJ 270, CA (refd) Legislation referred to Courts of Judicature Act 1964 s 69(1) Rules of the Court of Appeal 1994 r 4 Rules of the High Court 1980 O 15 rr 3, 6(2)(b) Appeal from: Civil Appeal No W-02432 of 2004 (Court of Appeal, Putrajaya)

726

Malayan Law Journal

[2011] 1 MLJ

Malik Imtiaz Sarwar (Khor See Yimn with him) (Thomas Philip) for the appellant. Shamsul Bahrin Manaf (Shook Lin & Bok) for the rst respondent. Harpal Singh (Renu Zechariah and G Ragumaren with him) (G Ragumaren & Co) for the second to sixth respondents. Alauddin PCA: INTRODUCTION [1] Appeals Nos 02()36 of 2009(W), 02()37 of 2009(W) and 02()38 of 2009(W) were all set for hearing before us on 18 May 2010. [2] Upon the request of the parties concerned, we proceeded to hear Appeal No 02()37 of 2009(W) only. It was also agreed by all parties concerned that the result of this appeal would bind the other two appeals. [3] The appeal is against the decision of the Court of Appeal (COA) dated 8 May 2009 (the decision) by which the COA allowed the application by the second to sixth respondents (the interveners) to intervene (the intervener application) into the COA Civil Appeal No W-02432 of 2004. The application to intervene was made in the appeal. [4] Leave to appeal was granted by the Federal Court to the appellant on 12 October 2009 on the following question:

Whether the test for intervention by beneciaries to the Estate into proceedings brought by administrators of the Estate at the High Court is the same as that for appellate proceedings.

[5] Leave to appeal was also granted to Shorga Sdn Bhd (appellant in Appeal No 02()38 of 2009(W)) and Raja Rajmah bt Raja Chik & Ors (appellants in Appeal No 02()36-of 2009(W)) on the same date and orders were made that a common record of appeal be led for the purposes of the three appeals. Appeals have also been lodged by the appellants in the other two appeals. [6] The position taken by each of the three appellants is the same ie that the decision was erroneous and ought to be set aside for there having been no basis in law and/or fact for the COA to have made the decision. In that regard, the COA ought to have dismissed the intervener application with costs. BACKGROUND FACTS [7] The material facts pertaining to the intervener application are as follows: (a) The rst respondent, Amanah Raya Bhd (ARB) was appointed as the

[2011] 1 MLJ

Chong Fook Sin v Amanah Raya Bhd (as the administrator for the estate of Raja Nong Chik bin Raja Ishak, deceased) & Ors (Alauddin PCA)

727

administrator of the estate of Raja Datuk Nong Chik bin Raja Ishak (the deceased) by way of an order of court dated 17 December 1996 granted in Kuala Lumpur High Court Petition No S131391 of 1996. As a matter of fact this was a consent order (please see para 3 p 71 of the record of appeal Vol 1/5, ARBs statement of claim dated 5 August 1998). (b) ARB was at all material times and still is the administrator of the estate of the deceased. (c) In August 1998, ARB commenced proceedings against the 13 defendants including all the appellants here in Kuala Lumpur High Court S222546 of 1998 (the ARB claim). The claim was in respect of an alleged conspiracy to defraud the estate of the deceased pertaining to certain shares alleged to have been owned by the deceased. (d) Signicantly, the interveners (second to sixth respondents) had as beneciaries to the estate of the deceased in Kuala Lumpur High Court Suit No D522975 of 1994 instituted proceedings of a similar nature against all the appellants in the appeals except the appellant herein (the prior claim). (e) An application was then made to strike out the claim by various defendants thereto. The High Court had on 9 March 1998 struck out the said claim (see record of appeal Vol 4/5, pp 437441). (f ) The appointment of ARB was then agreed to by the disputing parties. (g) By the admission of the interveners, they had caused ARB to le the ARB claim (see record of appeal Vol 5/5 p 444). [8] As mentioned above, the ARB claim was led in August 1998.

[9] The claim proceeded to case management on more than ten occasions. [10] Following from this, trial dates were xed from 2 to 6 June 2003. These dates were however vacated by reason of court vacation.

[11] The next trial date was xed from 25 to 26 February 2004. An application was led by ARB for discovery/release of certain documents. Quite clearly at that point of time ARB was not in a position to commence trial. It was again adjourned to 6 April 2004. In adjourning the trial to 6 April 2004, the learned trial judge issued several directions and had further directed the trial to proceed on 6 April 2004 failing which he would strike out the matter.

728

Malayan Law Journal

[2011] 1 MLJ

[12] On 6 April 2004, ARBs solicitors sought an adjournment on the grounds that they had led an application to discharge themselves as solicitors. Submissions were made by the respective parties. The learned judge reserved his decision to 7 April 2004. [13] On 7 April 2004, the learned judge allowed the application by ARBs solicitors for discharge but denied the application for adjournment. ARB conceded that it was not ready to proceed with the trial as no witnesses were present. [14] On that basis the learned trial judge struck out the ARB claim. [15] ARB on 28 April 2004 appealed to the COA against that decision to strike out its claim. [16] On 12 November 2008 the interveners led the intervener application. This was ten years after the commencement of the ARB claim and four years after having knowledge that the ARB claim had been struck out. (See record of appeal Vol 4/5 at pp 353355). [17] The basis of the intervener application was particularised as follows: (a) to ensure that all matters may be effectively and completely determined and adjudicated upon; and (b) to lend all assistance, knowledge and any background information that may be of assistance. [18] In view of the circumstances set out above, the appellant here opposed the intervener application, in essence, on the following primary grounds: (a) the interveners did not have any basis in fact and/or law to intervene in that the intervener did not have any legal interest in the subject of the appeal. In this regard: (i) the ARB claim was an estate claim instituted by the administrator. Beneciaries do not have an interest in the estate of a deceased person until administration is complete and distribution made. The estates interest are the responsibility of the administrator of the estate; and (ii) in any event, the appeal was concerned only with the correctness of the decision to strike out the ARB claim and not the merits of the ARB claim. This was a matter in which the interveners had not been involved in;

[2011] 1 MLJ

Chong Fook Sin v Amanah Raya Bhd (as the administrator for the estate of Raja Nong Chik bin Raja Ishak, deceased) & Ors (Alauddin PCA)

729

(iii) the question of the interveners right to commence action had been put to rest when the prior claim was struck out. There had been no appeal against that decision by the interveners. There was as such an issue estoppel which tied down the interveners; and (iv) there had further been inordinate delay on the part of the interveners. Further, they had not sought to intervene in the ARB claim at all. THE DECISION OF THE COURT OF APPEAL

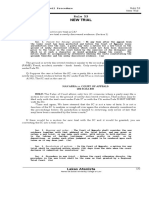

[19] The Court of Appeal however allowed the intervener application. In concluding that there were merits in the said application, the Court of Appeal took the view that: (a) O 15 r 6(2)(b) of the Rules of the High Court 1980 (RHC) applied by reason of a lacuna in the Rules of the Court of Appeal 1994 (RCA) and the operation of r 4 of the RCA; (b) the interveners had a benecial interest which fullled the test of establishing their interest for the purposes of obtaining leave; and

(c) the said benecial interest clearly and directly related to the subject matter of the appeal. THE APPEAL

[20] Before us the decision of the COA was attacked on the following grounds: (a) The COA erred in law and/or fact in concluding that the second to sixth respondents (the interveners) had legal basis to intervene into the proceedings at the COA (the appeal) as they were lawful beneciaries and as such they had benecial interest clearly and directly related to the subject matter of the appeal. (b) The COA erred in law and/or fact when it allowed the interveners to intervene into the proceedings at the COA when the interveners earlier civil suit in D522975 of 1994 (prior claim) on the same subject matter had been struck out, thus necessarily allowing the interveners to circumvent the principle of res judicate and/or issue estoppel. (c) The COA erred in law and/or fact in failing to appreciate that the test for intervention into appellate proceedings is the same as that for intervention into High Court proceedings. (d) The COA erred in law and/or in fact by failing to: (i) apply the express language of O 15 r 3 of the RHC 1980 read with r 4 of the RCA 1994;

730

Malayan Law Journal

[2011] 1 MLJ

(ii) distinguish a legal interest from a mere benecial interest, the former capable of satisfying the term in Pegang Mining Co Ltd v Choong Sam & Ors [1969] 2 MLJ 52 (PC); and (iii) in any event, failing to distinguish the subject matter of the civil suit from the subject matter of the appeal. [21] We will begin by restating the question posed for determination by this court ie:

Whether the test for intervention by beneciaries to the estate into proceedings brought by administrators of the estate at the High Court is the same as that for appellate proceedings.

[22] In the context of this appeal our view is that the question necessarily requires a consideration of two separate matters: (a) whether the High Court test is applicable; and (b) if so, whether the Court of Appeal correctly determined the intervener application. APPLICABILITY OF THE HIGH COURT TEST [23] The law in respect of evaluating intervener applications at rst instance had been laid down by the Privy Council in Pegang Mining Co Ltd v Choong Sam & Ors [1969] 2 MLJ 52 (PC). [24] The decision in Pegang Mining was adopted by the then Supreme Court in Tohtonku Sdn Bhd v Superace (M) Sdn Bhd [1992] 2 MLJ 63; [1992] 2 CLJ 1153; [1992] 1 CLJ 344 (Rep). [25] In Tohtonku Sdn Bhd the then Supreme Court had this to say:

It is settled law, on the authorities, that a party may be added if his legal interests will be affected by the judgment in the action but not if his commercial interests alone would be affected: per Lord Diplock in Pegang Mining Co Ltd v Choong Sam & Ors at pp 5556.

[26] This is reected by O 15 r 6(2)(b) of the RHC which provides:

(a) Only a person who ought to have been joined as a party or whose presence before the court is necessary to ensure that all matters in dispute in the cause or matter may be effectually and completely determined and adjudicated; or I

[2011] 1 MLJ

Chong Fook Sin v Amanah Raya Bhd (as the administrator for the estate of Raja Nong Chik bin Raja Ishak, deceased) & Ors (Alauddin PCA)

731

(b) whether there is a question or issue arising out of or relating to or connected with any relief or remedy claimed in the cause or matter which in the opinion of the court it would be just and convenient to determine as between him and that party as well as between the parties to the cause or matter.

[27] The RCA are silent as to intervener applications. There is no provision which is in pari materia to O 15 r 6(2)(b) of the RHC, above. [28] However, s 69(1) of the Courts of Judicature Act 1964 (CJA) provides that the COA shall have all the powers and duties, as to amendment or otherwise, of the High Court [29] Rule 4 of the RCA provides:

Where no other provision is made by any written law or by these Rules, the procedure and practice in the Rules of the High Court 1980 [P.U. (A)50/1980] shall mutatis mutandis apply.

[30] Based on the foregoing provisions, we would say that it stands to reason that: (a) the COA does have jurisdiction/power to determine an intervener application;

(b) the material provision is O 15 r 6(2)(b) of the RHC read with r 4 of the RCA; and (c) the test entrenched in that provision must, in our view, necessarily be moulded (mutatis mutandis) to suit the circumstances of the Court of Appeal.

[31] On that footing, it is our judgment that the test of legal interest would still be applicable. However the legal interest in issue must be an interest in the subject matter of the appeal before the COA. [32] It would be observed that in some cases, the subject matter of the appeal is the same as the subject matter in the High Court. In such cases, the legal interest would be identical for both. [33] However, there could arise situations where the subject matter of the appeal of the COA is separate and distinct from, although connected to, the subject matter of the proceedings at the High Court. The present appeal presents one such situation. The interveners assert an interest by reason of being beneciaries in the estate of the deceased. This is more relevant to the proceedings in the High Court as they stood prior to being struck off. The

732

Malayan Law Journal

[2011] 1 MLJ

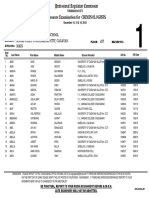

appeal only concerns ARBs non-compliance with the unless order made against it. This did not and could not involve the interveners qua beneciaries. [34] In such situations, it is incumbent upon the proposed intervener to establish a legal interest in the subject matter of the appeal before the COA by reference to the matter under consideration in that court. An indirect interest cannot amount to a legal interest. [35] In addition, the intervener application must be made at rst instance where the proposed interveners had knowledge of the proceedings in the High Court and the opportunity to take the necessary steps (see Tradium Sdn Bhd v Zain Azahari bin Zainal Abidin & Anor [1995] 1 MLJ 668; [1996] 2 CLJ 270 and Fairview Schools Bhd v Indrani a/p Rajaratnam & Ors (No 1) [1998] 1 MLJ 99; [1998] 1 CLJ 285. [36] In this regard opportunity must be understood as meaning legal avenue and entitlement to make such an application. Quite apart from the requisite legal interest, an applicant must establish that he is not precluded by any other circumstances from making such an application. [37] Such precluding circumstances would include a prior determination of the courts that gave rise to an issue estoppel such as to attract the doctrine of res judicata. A party so impeded would not be in a position to seek leave to intervene. [38] Based on the foregoing, we are unanimous that the question before the court must be answered in the afrmative subject to the qualications noted above. WHETHER THE COURT OF APPEAL ERRED [39] Having heard submissions before us by both parties and having referred to the authorities cited for and against, we must say, with utmost respect, that the COA erred for the following reasons: (a) The interveners did not have the requisite legal interest as the subject matter of the appeal before the COA was the consequence of non-compliance with the unless order on the part of ARB. This was a matter in which the interveners were not involved at all. (b) Further, even if the interveners were beneciaries, they did not have legal interest in the estate of the deceased pending the administration of the same. In Chor Phaik Har v Farlim Properties Sdn Bhd [1997] 3 MLJ 188; [1997] 4 CLJ 393 the Federal Court held that, in law, a beneciary under an intestacy has no interest or property in the personal estate of a deceased

[2011] 1 MLJ

Chong Fook Sin v Amanah Raya Bhd (as the administrator for the estate of Raja Nong Chik bin Raja Ishak, deceased) & Ors (Alauddin PCA)

733

person until the administration of the latters estate is complete and distribution made according to the law of distribution of the intestate estate (see also Law Hock Key & Anor v Yap Meng Kan & Ors [2008] 3 CLJ 470 and Hong Leong Bank Bhd (formerly known as Hong Leong Finance Bhd) v Staghorn Sdn Bhd and other appeals [2008] 2 MLJ 622; [2008] 2 CLJ 121). (c) The grounds advanced by the interveners in support of their application ie to ensure due determination of all matters in controversy and to lend assistance do not in any way go to establishing a legal interest. The interveners were circumscribed by the grounds on which they moved the COA. (d) Any dissatisfaction concerning the way in which ARB was conducting itself as administrator of the estate of the deceased was and is a matter that is to be taken up in an entirely different forum. (e) Further, the interveners did not seek to intervene at the rst available opportunity. In this regard the interveners had knowledge of the ARB claim. They had in fact caused the ling of the ARB claim by a complaint about the defendants in the High Court. The interveners also supplied information and documents to ARB. (f ) The interveners did not seek to apply to intervene in the High Court at any point in time.

(g) The intervener application was led some ten years after the commencement of the ARB claim and approximately four years after the ARB claim had been struck off. (h) No explanation was given as to the delay or the interveners reasons for not having made an application in the High Court. (i) Further, the interveners were not legally entitled to move an application to intervene because they had themselves commenced the Prior Action against the defendants and this had been struck out on the application of the various defendants in 1998. The basis of the striking out was the appointment of ARB as the administrator of the estate of the deceased. There was as such a determination of the capacity and interest of the interveners to bring a suit. An issue estoppel arose and the interveners were bound by the doctrine of res judicata. CONCLUSION [40] In view of what we have said above, we would allow this appeal with

734

Malayan Law Journal

[2011] 1 MLJ

costs here and below. We would also allow Appeal Nos 02()36 of 2009(W) and 02()38 of 2009(W) with costs here and below. We also order that the deposits be refunded to the appellants. Appeals allowed with costs here and below.

Reported by Kohila Nesan

You might also like

- Goodness Breeds GoodnessDocument1 pageGoodness Breeds GoodnessDIN08No ratings yet

- Negative Positive Is The KeyDocument1 pageNegative Positive Is The KeyDIN08No ratings yet

- Be Jolly GoodDocument1 pageBe Jolly GoodDIN08No ratings yet

- Body Is Just An Empty ShellDocument1 pageBody Is Just An Empty ShellDIN08No ratings yet

- See and KnowDocument1 pageSee and KnowDIN08No ratings yet

- Nothing New Under The SunDocument1 pageNothing New Under The SunDIN08No ratings yet

- Celestial PowerDocument1 pageCelestial PowerDIN08No ratings yet

- Sleep Is ImportantDocument1 pageSleep Is ImportantDIN08No ratings yet

- Tesla's Secret Radiant Energy Theory ExplainedDocument7 pagesTesla's Secret Radiant Energy Theory ExplainedDIN08No ratings yet

- La Extraña Vida de Nikola Tesla PDFDocument47 pagesLa Extraña Vida de Nikola Tesla PDFrecursoseducNo ratings yet

- Technology Always ChangesDocument1 pageTechnology Always ChangesDIN08No ratings yet

- Make Your Own DestinyDocument1 pageMake Your Own DestinyDIN08No ratings yet

- Just Be YourselfDocument1 pageJust Be YourselfDIN08No ratings yet

- Think Before You DoDocument1 pageThink Before You DoDIN08No ratings yet

- Stay StrongDocument1 pageStay StrongDIN08No ratings yet

- True Love Has True FlavourDocument1 pageTrue Love Has True FlavourDIN08No ratings yet

- Make MeccaDocument1 pageMake MeccaDIN08No ratings yet

- Love Is The ThingDocument1 pageLove Is The ThingDIN08No ratings yet

- Good Becomes GoodDocument1 pageGood Becomes GoodDIN08No ratings yet

- Sunday Is For The SUNDocument1 pageSunday Is For The SUNDIN08No ratings yet

- Everybody Lies GenerallyDocument1 pageEverybody Lies GenerallyDIN080% (1)

- Work Smarter and HarderDocument1 pageWork Smarter and HarderDIN08No ratings yet

- Love Is LightDocument1 pageLove Is LightDIN08No ratings yet

- Truth Is HiddenDocument1 pageTruth Is HiddenDIN08No ratings yet

- God Is WiseDocument1 pageGod Is WiseDIN08No ratings yet

- Be Thankful and Your Life Be ThankedDocument1 pageBe Thankful and Your Life Be ThankedDIN08No ratings yet

- God Is LoveDocument1 pageGod Is LoveDIN08No ratings yet

- Article - The Power of WaterDocument4 pagesArticle - The Power of WaterDIN08No ratings yet

- Violence Breeds ViolenceDocument1 pageViolence Breeds ViolenceDIN08No ratings yet

- Biomagnetic Healing by Gary Null PDFDocument80 pagesBiomagnetic Healing by Gary Null PDFYuldash100% (7)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Request of CADocument16 pagesRequest of CADenise CuizonNo ratings yet

- RA CUSTOMSBROKER MANILA Nov2018 PDFDocument84 pagesRA CUSTOMSBROKER MANILA Nov2018 PDFPhilBoardResultsNo ratings yet

- Tuguegarao Major in Filipino PDFDocument11 pagesTuguegarao Major in Filipino PDFPhilBoardResultsNo ratings yet

- Summary - Justice Abdulai V Attorney-General (2022) - Ghana Center For DemocratiDocument5 pagesSummary - Justice Abdulai V Attorney-General (2022) - Ghana Center For DemocratiAUXILIUM LEGALISNo ratings yet

- Newly Discovered EvidenceDocument2 pagesNewly Discovered EvidenceEA CemNo ratings yet

- A.M. No. RTJ 04 1868 Re Request of Judge Tito G. Gustilo That The Second 25Document10 pagesA.M. No. RTJ 04 1868 Re Request of Judge Tito G. Gustilo That The Second 25Jey-eel NastorNo ratings yet

- Schreibman Contributions 2011-2012Document8 pagesSchreibman Contributions 2011-2012David LombardoNo ratings yet

- Bigamy PP V NepomucenoDocument5 pagesBigamy PP V NepomucenoFlorenz Ross MosqueraNo ratings yet

- CrimPro Cases R110-115Document7 pagesCrimPro Cases R110-115saeNo ratings yet

- Prince William County Sheriff's Office Roster, FOIA 2/13/2023Document6 pagesPrince William County Sheriff's Office Roster, FOIA 2/13/2023OpenOversightVA.orgNo ratings yet

- Gary Born - International Comercial Arbitration - Vol - II - Pp. 2887-2933Document25 pagesGary Born - International Comercial Arbitration - Vol - II - Pp. 2887-2933Fábio Machado MalagóNo ratings yet

- Crimpro SyllabusDocument7 pagesCrimpro SyllabusArvene FloresNo ratings yet

- Power of Review - Labour Courts or Industrial TribunalsDocument19 pagesPower of Review - Labour Courts or Industrial TribunalsShivam BhargavaNo ratings yet

- Contracts Final DraftDocument33 pagesContracts Final DraftShreya SinghNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law ParliamentDocument26 pagesConstitutional Law ParliamentAshwina NamtaNo ratings yet

- Law Firms List 2Document13 pagesLaw Firms List 2Reena ShauNo ratings yet

- Maria Filomena D. Singh copyrighted documentDocument50 pagesMaria Filomena D. Singh copyrighted documentGiovanni Garcia100% (4)

- Information For Violation of R.A. 9262Document2 pagesInformation For Violation of R.A. 9262lolo09832q55No ratings yet

- Sept 2013 LET MNL Room Assignment - TLEDocument188 pagesSept 2013 LET MNL Room Assignment - TLECoolbuster.NetNo ratings yet

- Children's Law Center 2012 Annual ReportDocument20 pagesChildren's Law Center 2012 Annual ReportMarsh Law Firm PLLCNo ratings yet

- RA CRIM TUGUE Dec2018 PDFDocument144 pagesRA CRIM TUGUE Dec2018 PDFPhilBoardResultsNo ratings yet

- United Kingdom - Judicial SystemDocument1 pageUnited Kingdom - Judicial SystemJuly Zerpa RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Deputy President William Ruto IMPEACHMENT MOTION Scheduled For Tuesday - June 02 2020Document9 pagesDeputy President William Ruto IMPEACHMENT MOTION Scheduled For Tuesday - June 02 2020kenya 411No ratings yet

- Social Studies Tugue PDFDocument57 pagesSocial Studies Tugue PDFPhilBoardResultsNo ratings yet

- ARCH0117 Mla e PDFDocument58 pagesARCH0117 Mla e PDFPhilBoardResultsNo ratings yet

- PRC Room Assignment For July 2011 Nursing Board Exam (Tuguegarao)Document100 pagesPRC Room Assignment For July 2011 Nursing Board Exam (Tuguegarao)PhilippineNursingDirectory.comNo ratings yet

- Ifugao - MunDocument26 pagesIfugao - MunireneNo ratings yet

- RA ChemTech CDO Oct2019 PDFDocument20 pagesRA ChemTech CDO Oct2019 PDFPhilBoardResultsNo ratings yet

- Lok Sabha SpeakerDocument2 pagesLok Sabha Speakersagari.bs25No ratings yet

- The Law Making Process in UgandaDocument4 pagesThe Law Making Process in UgandaremojamwaNo ratings yet