Professional Documents

Culture Documents

N: A 2013 T P S - Mtsu: Ewsletter Ugust Eaching Rimary Ources

Uploaded by

CassandraKBennettOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

N: A 2013 T P S - Mtsu: Ewsletter Ugust Eaching Rimary Ources

Uploaded by

CassandraKBennettCopyright:

Available Formats

T EACHING

WELCOME!

P RIMARY S OURCES MTSU N EWSLETTER : A UGUST 2013 V OLUME 5, I SSUE 8

WITH

U PCOMING E VENTS :

August 6(Chattanooga) Using Primary Sources To Address Common Core, Hamilton County Schools In service. Times TBA. September 13 (Knoxville) Using Primary Sources to Address Common Core at the East Tennessee History Center from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. EST. To register email oakley@easttnhistory.org. September 14 (Collierville) "The Civil War Experience in West Tennessee" Workshop held in partnership with Morton Museum of Collierville at Lucius E. and Elsie C. Burch, Jr. Library in Collierville from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Click here for more information. To register, email museum@ci.colliervill e.tn.us or call (901) 4572650. September 26 (Murfreesboro) Primary Sources and Literacy-Based Activities at the Heritage Center from 4 p.m. to 6 p.m. Open to middle and high school teachers. To register, email kira.duke@mtsu.edu

Teaching with Primary SourcesMiddle Tennessee State University, administered by the Center for Historic Preservation, engages learners of all ages in using primary sources to explore major issues and questions in many different disciplines. Contact: Stacey Graham or Kira Duke at (615) 898-2947 or www.mtsu.edu/tps

N EWS

Join TPS-MTSU at the Tennessee Civil War Sesquicentennial Signature Event in Chattanooga on October 9-12. Events kick off with a teacher workshop facilitated by TPS-MTSUspots are still available for the workshop on Thursday, October 10. For a complete schedule of events and speakers visit http://www.tnvacation.com/ civil-war/events/. To register for the October 10th workshop, email kira.duke@mtsu.edu. We have two new lesson plans available: Science and Technology: Then and Now (for 8th grade) and Culture Clash: Three Views of Columbus (for 10th grade). Both of these lesson plans were written by Rob Hooper, Daniel McKee Alternative School, Rutherford County Schools.

A WESOME S OURCE OF THE MONTH :

T HEME : W ESTWARD M IGRATION

Because the first European settlements in the future United States were all on the east coast, the whole history of the development of our country is one of westward migration: first, inland from the coast, then across the Appalachians, into the Midwest, into the Great Plains, across the Rockies, and beyond the Pacific Coast. Within Tennessee, migration went westward along the river and overland routes, and then into the western division of the state after the treaties with the Chickasaw by 1818. Maps make great primary sources for exploring this topic, as do pioneers letters and diaries, and photographs. From the Cumberland Gap to Lewis & Clark to Hawaii, the Library of Congress Web site has resources to make these stories come alive.

Wagon tracks on Old Oregon Trail. Scottsbluff, Nebraska [1941] The wagon ruts left by settlers traveling the Oregon Trail were so deep in places that they were still visible in the 1940s, as shown in this photograph.

Content created and featured in partnership with the TPS program does not indicate an endorsement by the Library of Congress.

N EWSLETTER : A UGUST 2013

P AGE 2

L ESSON I DEA T HE D AKOTA W AR OF 1862

In 1862, two wars were being fought in the United States, one over slavery in the South and another over Dakota land on the Minnesota frontier. The Dakota War (or Uprising) started in 1862 after many years of broken treaties. The weekly public radio show This American Life recently did an episode on the sesquicentennial of this war. For additional information on this topic, see this online exhibit. Divide the class into two groups; have them listen to or read act one or two of the Little War on the Prairie episode (assign both groups the prologue). Have students take notes on the events, names, tribes, and places discussed in their portion of episode. From these notes, have students search for several terms on the Library of Congress Web site. Some examples are Mankato, Jane Ka-ka-kel, Little Crow, a G. Swisshelm, Little Crow, Mdewakantons, and Wahpekute. As chief of the Mdewakanton they do this, have them consider these questions: What were the Sioux [1858 or 1859, detail] consequences of the westward migration in Minnesota? What led to the uprising? Where did these events occur? How did the two sides differ in their 1860s reporting and current memory of these events? After students have identified key images, have each group present the information from their act along with images and any new information they found in their research. This lesson idea can be adapted to meet state curriculum standards for Social Studies grades 4, 5, 7, and 8; High School U. S. History Era 6 (Standard 3: Geography and Standard 5: History); and Common Core State Standards for grades 6-12 (Speaking & Listening).

Important Links: The Lewis and Clark Expedition (Themed Resources) Westward Expansion (Primary Source Set from TPS-MTSU ) Westward Expansion: Encounters at a Cultural Crossroads (Primary Source Set) Primary source collections on American Expansion Westward Expansion & Reform (Americas Library) American Treasures: To the West (exhibition) Wedding of the Rails (Today in History)

L ESSON I DEA L IVING IN A S OD H OUSE

The Homestead Act of 1862, which provided free land to settlers who were willing to farm it, initiated a wave of migration to the Great Plains territories west of the Mississippi River. The geography of the Great Plains was very different than it was east of the Mississippi. For instance, wide, grassy plains did not have enough trees to create an adequate supply of lumber. Consequently, many homesteaders resorted to a natural resource that was in abundancedirtto build their houses. Divide students into 5 groups and provide each group with one of the following images: Sod house near Milton, Mexican Catholic Church, Mr. & Mrs. David Vincent, In the good old days, and An Educational resort. Have Mr. & Mrs. David Vincent and daughter, Martha, by each group follow the observe-reflect-question process in the Primary their sod house : near White River, South Dakota. Source Analysis Tool, and click on Bibliographic Information (above each [191-?] photograph) to read the full titles and summaries for clues. Then, have students read some historical background information here. Have each group present and explain its photo to the class. After presentations, have students read Letter from Mattie V. Oblinger to Thomas Family, May 19, 1873. (You may wish to have them proofread it, as it contains many grammatical and punctuation errors.) Discuss as a class: how does Mattie like living in a sod house? What topics concern her daily life? Does what she writes about reflect what students saw in the group photographs? (For more about the Oblinger family, see this special presentation.) For homework, have students write letters like Matties from the points of view of the people in the photographs. EXTENSION IDEA: students can also read excerpts from Laura Ingalls Wilders Little House on the Prairie books and discuss the Ingalls Familys experiences as homesteaders. These ideas can be adapted to meet curriculum standards for grade 5 Social Studies (History, Era 6) and Common Core State Standards for grade 5 (Reading: Foundational Skills, Reading: Informational Text, and Writing).

N EWSLETTER : A UGUST 2013

P AGE 3

L ESSON I DEA D RAWING THE W ESTWARD M IGRATION

Tell your students that you are going to show them three drawings created by a man named Daniel Jenks. He lived in Rhode Island and first traveled to the West by boat in 1849 to take part in the California Gold Rush. He returned home but then traveled out West again via covered wagon in 1859. Ask students if they think they would have preferred traveling to the West via boat or via covered wagon. After his second trip, Jenks sketched what he had seen and sent the drawings home to his sister. Show the children these three drawings: Pretty camp - Rocky Mountains, Cherokee Pass, Rocky Mountains, and Camp 120, Eagle Lake, Sierra Nevadas. Ask them which is their favorite. Next, focus on Pretty camp - Rocky Mountains. Ask the students to describe what they see. How much of the drawing is taken up by the people and wagons? The mountains and trees? What are the Camp 120, Eagle Lake, Sierra Nevadas [1860] people doing? Next look at Cherokee Pass. How is it different from the previous drawing, both in content and form? Why do you think Jenks left people out of this drawing? Finally, look at Camp 120, Eagle Lake, Sierra Nevadas. How is it different than the previous drawing? As a class, compose a letter back to Daniel Jenks from his sister commenting on the drawings. If you have time, read Gold Fever, written by Verla Kay and illustrated by S.D. Schindler, to the students. This lesson idea can be adapted to meet state curriculum standards for grades K-2 Social Studies (History and Geography) and Art (Evaluation) and Common Core State Standard for grades K-2 English/Language Arts (Reading: Informational Text).

F EATURED F EATURE N EW L ESSON P LAN : M ANIFEST D ESTINY

Manifest Destiny: War on the Plains, written by Aaron Walls, from Christiana Middle School in Rutherford County, examines the Indian Wars of the late nineteenth century and the idea of manifest destiny through multiple visual, written, and oral history sources by Turner, Custer, Tecumseh, Crazy Horse, and more. By the conclusion of the lesson, students will be able to define manifest destiny and how it was used to justify war with Native American tribes and their removal to reservations. The lesson begins by reviewing what students know about the Indian Wars and key figures from the conflicts. Using the provided PowerPoint, the class will view a series of historic photographs and compare those images with the idealization of manifest destiny. Next students will read a series of speeches and writings from key figures. Prior to completing their readings, students should complete an inAmerican progress [1873] formal writing assignment that includes their hypothesis about their sources and what they expect to find. Provide students with the readings discussion questions worksheet (included in the lesson) and use this as the basis for your class discussion the next day. Conclude your class discussion by asking your students how these sources have changed their overall perceptions of manifest destiny and the events and individuals they have read about. How has their understanding of the impact of westward migration changed? This lesson plan meets curriculum standards for grades 8 and 11 U.S. History and Common Core State Standards for English/ Language Arts. You will find a complete list of curriculum standards met included in the lesson plan.

N EWSLETTER : A UGUST 2013

P AGE 4

G ATEWAY TO THE G OLD F IELDS

U.S. S TRETCHES TO THE P ACIFIC

Sacramento city, Ca. from the foot of J. Street, showing I., J., & K. Sts. with the Sierra Nevada in the distance / / C. Parsons ; drawn Dec. 20th 1849 by G.V. Cooper ; lith. of Wm. Endicott & Co., N. York. What first catches your eye when you look at this image? From this image, how do you assume that people and goods arrived in Sacramento? What natural features do you see? Can you see any people (try the jpg version)?

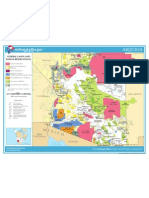

Map of the Oregon Territory. [1871, detail] How did the U.S. finally stretch its territory to the Pacific Ocean? Answer: through the creation of the Oregon Territory and through the Treaty of Guadaloupe Hidalgo. Read the Today in History articles about these events. What lands did each add to the U.S.? Who owned/lived in these lands before the U.S. acquired them? How did reaching from the Atlantic to the Pacific affect the identity of the nation?

Y OU S HOULD M OVE H ERE

EXPANSION INTO INDIAN LANDS

Homes For Immigrants. Inducements Offered In West Tennessee. [1869, detail] What surprises you about this broadside? What are the benefits listed that would encourage someone to move to Union City? Why do you think this was created? Why would city leaders be encouraging immigrants to move to the area? What immigrant groups might have been targeted?

Sioux chiefs [1905, detail] Westward migration brought whites into contact with the Wests prior inhabitants, Native Americans. As various tribal lands were fast eclipsed by white settlement, Americans were fascinated by Indian culture. How does a photograph like this one (taken by Edward Curtis) contribute to a romanticized view of Native Americans? (Also see our lesson plan on the Myth of the Vanishing Race.)

You might also like

- Ada's Journal and Emma's Letters: The Civil War Era Journal and Letters of Emma Peck: The Pecks of Mossy CreekFrom EverandAda's Journal and Emma's Letters: The Civil War Era Journal and Letters of Emma Peck: The Pecks of Mossy CreekRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- N: J 2013 T P S - Mtsu: Ewsletter ULY Eaching Rimary OurcesDocument4 pagesN: J 2013 T P S - Mtsu: Ewsletter ULY Eaching Rimary OurcesCassandraKBennettNo ratings yet

- Great Basin Indians: An Encyclopedic HistoryFrom EverandGreat Basin Indians: An Encyclopedic HistoryRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Unit4 Early19CenturyDocument2 pagesUnit4 Early19CenturyShower of RosesNo ratings yet

- Tribe, Race, History: Native Americans in Southern New England, 1780–1880From EverandTribe, Race, History: Native Americans in Southern New England, 1780–1880Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- N: N 2013 T P S - Mtsu: Ewsletter Ovember Eaching Rimary OurcesDocument4 pagesN: N 2013 T P S - Mtsu: Ewsletter Ovember Eaching Rimary OurcesCassandraKBennettNo ratings yet

- All That Is Native and Fine: The Politics of Culture in an American RegionFrom EverandAll That Is Native and Fine: The Politics of Culture in an American RegionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- ECU Journal 1960-1961Document33 pagesECU Journal 1960-1961Katherine SleykoNo ratings yet

- Reconstructing Appalachia: The Civil War's AftermathFrom EverandReconstructing Appalachia: The Civil War's AftermathRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (1)

- Steven C. Schulte-Wayne Aspinall and The Shaping of The American West (2002)Document337 pagesSteven C. Schulte-Wayne Aspinall and The Shaping of The American West (2002)Maurizio80No ratings yet

- William F. Tolmie at Fort Nisqually: Letters, 1850-1853From EverandWilliam F. Tolmie at Fort Nisqually: Letters, 1850-1853Steve A. AndersonNo ratings yet

- Wayne Suttles DissertationDocument4 pagesWayne Suttles DissertationWhereCanYouBuyResumePaperUK100% (1)

- Growing Up Native ThesisDocument8 pagesGrowing Up Native ThesisKarla Adamson100% (1)

- Removable Type: Histories of the Book in Indian Country, 1663-1880From EverandRemovable Type: Histories of the Book in Indian Country, 1663-1880Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- U1 Themeacrtime Way SeDocument12 pagesU1 Themeacrtime Way SePatrizia Lbt Cm100% (1)

- Emilie Davis's Civil War: The Diaries of a Free Black Woman in Philadelphia, 1863–1865From EverandEmilie Davis's Civil War: The Diaries of a Free Black Woman in Philadelphia, 1863–1865No ratings yet

- No More HeroesDocument9 pagesNo More HeroesvolodeaTisNo ratings yet

- Teacher GuideDocument7 pagesTeacher Guideapi-274179099No ratings yet

- On the Turtle's Back: Stories the Lenape Told Their GrandchildrenFrom EverandOn the Turtle's Back: Stories the Lenape Told Their GrandchildrenNo ratings yet

- 1915, The CrisisDocument52 pages1915, The CrisisJide Ishmael AjisafeNo ratings yet

- This Land Is Their Land: The Wampanoag Indians, Plymouth Colony, and the Troubled History of ThanksgivingFrom EverandThis Land Is Their Land: The Wampanoag Indians, Plymouth Colony, and the Troubled History of ThanksgivingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- World History: Teacher: Mr. Riley Veal Grade 12Document4 pagesWorld History: Teacher: Mr. Riley Veal Grade 12api-315590402No ratings yet

- Curating the American Past: A Memoir of a Quarter Century at the Smithsonian National Museum of American HistoryFrom EverandCurating the American Past: A Memoir of a Quarter Century at the Smithsonian National Museum of American HistoryNo ratings yet

- Diary of Charles Lowell Walker (Vol.1)Document509 pagesDiary of Charles Lowell Walker (Vol.1)TaylorNo ratings yet

- Theme BasketDocument12 pagesTheme Basketapi-121449898No ratings yet

- SUNY Fall 2015 PDF CatalogDocument76 pagesSUNY Fall 2015 PDF CatalogreadalotbutnowisdomyetNo ratings yet

- Oral History Interview With Kurt VordemaierDocument49 pagesOral History Interview With Kurt VordemaierCassandraKBennettNo ratings yet

- The Autobiography of Citizenship: Assimilation and Resistance in U.S. EducationFrom EverandThe Autobiography of Citizenship: Assimilation and Resistance in U.S. EducationNo ratings yet

- Thesis Proposal Acceptance FormDocument17 pagesThesis Proposal Acceptance FormCassandraKBennettNo ratings yet

- The Foundations of Glen Canyon Dam: Infrastructures of Dispossession on the Colorado PlateauFrom EverandThe Foundations of Glen Canyon Dam: Infrastructures of Dispossession on the Colorado PlateauNo ratings yet

- Heritage Revitalization For Rowan Museum, Inc., Salisbury, NCDocument15 pagesHeritage Revitalization For Rowan Museum, Inc., Salisbury, NCCassandraKBennettNo ratings yet

- Ruin Nation: Destruction and the American Civil WarFrom EverandRuin Nation: Destruction and the American Civil WarRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Oral History Interview With Mrs. VordemaierDocument8 pagesOral History Interview With Mrs. VordemaierCassandraKBennettNo ratings yet

- Writing the South through the Self: Explorations in Southern AutobiographyFrom EverandWriting the South through the Self: Explorations in Southern AutobiographyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Park Theatre NR NominationDocument21 pagesPark Theatre NR NominationCassandraKBennettNo ratings yet

- Example Architectural Descriptions, McKenzie, TennesseeDocument2 pagesExample Architectural Descriptions, McKenzie, TennesseeCassandraKBennettNo ratings yet

- The Nation's Nature: How Continental Presumptions Gave Rise to the United States of AmericaFrom EverandThe Nation's Nature: How Continental Presumptions Gave Rise to the United States of AmericaNo ratings yet

- Example Tennessee Century Farms Program Press ReleasesDocument11 pagesExample Tennessee Century Farms Program Press ReleasesCassandraKBennettNo ratings yet

- Skulls and Keys: The Hidden History of Yale's Secret SocietiesFrom EverandSkulls and Keys: The Hidden History of Yale's Secret SocietiesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Park Theatre, McKenzie, Carroll County, Tennessee, Heritage Development PlanDocument125 pagesPark Theatre, McKenzie, Carroll County, Tennessee, Heritage Development PlanCassandraKBennettNo ratings yet

- From Western Deserts to Carolina Swamps: A Civil War Soldier's Journals and Letters HomeFrom EverandFrom Western Deserts to Carolina Swamps: A Civil War Soldier's Journals and Letters HomeNo ratings yet

- October 2014 Cassandra K Bennett ResumeDocument2 pagesOctober 2014 Cassandra K Bennett ResumeCassandraKBennettNo ratings yet

- On the Edge of Freedom: The Fugitive Slave Issue in South Central Pennsylvania, 1820–1870From EverandOn the Edge of Freedom: The Fugitive Slave Issue in South Central Pennsylvania, 1820–1870No ratings yet

- N: S 2013 T P S - Mtsu: Ewsletter Eptember Eaching Rimary OurcesDocument4 pagesN: S 2013 T P S - Mtsu: Ewsletter Eptember Eaching Rimary OurcesCassandraKBennettNo ratings yet

- Historic Spots in California: Fifth EditionFrom EverandHistoric Spots in California: Fifth EditionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- TPS-MTSU Women's Suffrage Links GuideDocument4 pagesTPS-MTSU Women's Suffrage Links GuideCassandraKBennettNo ratings yet

- Our Most Priceless Heritage: The Lasting Legacy of the Scots-irish in AmericaFrom EverandOur Most Priceless Heritage: The Lasting Legacy of the Scots-irish in AmericaNo ratings yet

- TPS-MTSU Newsletter October 2013Document4 pagesTPS-MTSU Newsletter October 2013CassandraKBennettNo ratings yet

- N: N 2013 T P S - Mtsu: Ewsletter Ovember Eaching Rimary OurcesDocument4 pagesN: N 2013 T P S - Mtsu: Ewsletter Ovember Eaching Rimary OurcesCassandraKBennettNo ratings yet

- Objects of Survivance: A Material History of the American Indian School ExperienceFrom EverandObjects of Survivance: A Material History of the American Indian School ExperienceNo ratings yet

- Practice Test Chapter 3 Migration Chapter 4Document10 pagesPractice Test Chapter 3 Migration Chapter 4cymafredNo ratings yet

- High Vistas: An Anthology of Nature Writing from Western North Carolina and the Great Smoky Mountains, Volume II, 1900-2009From EverandHigh Vistas: An Anthology of Nature Writing from Western North Carolina and the Great Smoky Mountains, Volume II, 1900-2009Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Portland Black Panthers: Empowering Albina and Remaking A CityDocument28 pagesPortland Black Panthers: Empowering Albina and Remaking A CityUniversity of Washington PressNo ratings yet

- Converging Empires: Citizens and Subjects in the North Pacific Borderlands, 1867–1945From EverandConverging Empires: Citizens and Subjects in the North Pacific Borderlands, 1867–1945No ratings yet

- Military History Map of 1854-1890 - Atlas of The Sioux Wars, Part 2Document51 pagesMilitary History Map of 1854-1890 - Atlas of The Sioux Wars, Part 2HistoricalMapsNo ratings yet

- The Men Who United the States: America's Explorers, Inventors, Eccentrics and Mavericks, and the Creation of One Nation, IndivisibleFrom EverandThe Men Who United the States: America's Explorers, Inventors, Eccentrics and Mavericks, and the Creation of One Nation, IndivisibleRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (23)

- AFS L37 OptDocument2 pagesAFS L37 OptCarlos María García ArbeloNo ratings yet

- American Pageant Chapter 1Document24 pagesAmerican Pageant Chapter 1oliver gross100% (1)

- The Rise and Fall of Lakota Empire - SCRIPTDocument8 pagesThe Rise and Fall of Lakota Empire - SCRIPTDhāraṇe KusalaNo ratings yet

- The Roar and the Silence: A History of Virginia City and the Comstock LodeFrom EverandThe Roar and the Silence: A History of Virginia City and the Comstock LodeNo ratings yet

- Western Expansion: Cause EffectDocument2 pagesWestern Expansion: Cause EffectGuljahan HanovaNo ratings yet

- A Season of Slaughter: The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, May 8–21, 1864From EverandA Season of Slaughter: The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, May 8–21, 1864Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Kobelco Hydraulic Excavator Sk290lc Sk330lc Service Manual 2Document24 pagesKobelco Hydraulic Excavator Sk290lc Sk330lc Service Manual 2pumymuma100% (35)

- Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836–1986From EverandAnglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836–1986Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Black Moon - The Minnecoujou Leader, by Ephriam DicksonDocument2 pagesBlack Moon - The Minnecoujou Leader, by Ephriam DicksonСтепан ВасильевNo ratings yet

- Social Studies Grade 5Document22 pagesSocial Studies Grade 5api-288156899No ratings yet

- Missing NounsDocument2 pagesMissing Nounsapi-295092435No ratings yet

- Maya-British Conflict at the Edge of the Yucatecan Caste WarFrom EverandMaya-British Conflict at the Edge of the Yucatecan Caste WarNo ratings yet

- Dat Zip Zone DirectoryDocument2 pagesDat Zip Zone DirectoryUsman KhanNo ratings yet

- One of The Most Pervasive Myths Surrounding The Superstition Mountains To This Very Day Is The Legend of The Black LegionDocument4 pagesOne of The Most Pervasive Myths Surrounding The Superstition Mountains To This Very Day Is The Legend of The Black LegionShazana ZulkifleNo ratings yet

- Parading Patriotism: Independence Day Celebrations in the Urban Midwest, 1826–1876From EverandParading Patriotism: Independence Day Celebrations in the Urban Midwest, 1826–1876No ratings yet

- Lesson 2 - Historic Tribes of Kansas 1Document9 pagesLesson 2 - Historic Tribes of Kansas 1api-30916099275% (4)

- The Civil War Soldiers' Orphan Schools of Pennsylvania 1864-1889From EverandThe Civil War Soldiers' Orphan Schools of Pennsylvania 1864-1889No ratings yet

- Lone Horn's Peace - Crow-Sioux Relations, by Kingsley BrayDocument21 pagesLone Horn's Peace - Crow-Sioux Relations, by Kingsley BrayСтепан ВасильевNo ratings yet

- Where These Memories Grow: History, Memory, and Southern IdentityFrom EverandWhere These Memories Grow: History, Memory, and Southern IdentityRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- UBC Geog 328 Class Notes: Constructing CanadaDocument104 pagesUBC Geog 328 Class Notes: Constructing CanadakmtannerNo ratings yet

- Chang and Eng Reconnected: The Original Siamese Twins in American CultureFrom EverandChang and Eng Reconnected: The Original Siamese Twins in American CultureNo ratings yet

- History of ColoradoDocument2 pagesHistory of ColoradoGayle OmisolNo ratings yet

- The Pembina and Turtle Mountain Metis AnDocument44 pagesThe Pembina and Turtle Mountain Metis AnSheri Ann HavenerNo ratings yet

- Reading ComprehensionDocument6 pagesReading ComprehensionShahid Khan StanadarNo ratings yet

- Map of Arizona - Federal Lands and Indian ReservationsDocument1 pageMap of Arizona - Federal Lands and Indian ReservationsHistoricalMapsNo ratings yet

- 684 MtnRangesDocument1 page684 MtnRangesTammy ReedNo ratings yet

- Description: Tags: Awards07-08Document4 pagesDescription: Tags: Awards07-08anon-353363No ratings yet

- Oregon TrailDocument31 pagesOregon TrailspamdetectorjclNo ratings yet

- Crow NationDocument14 pagesCrow NationGiorgio MattaNo ratings yet

- End of The Native AmericansDocument33 pagesEnd of The Native AmericansWill TeeceNo ratings yet

- American Continentalism and the Pursuit of Asian Commerce, 1845-1910Document14 pagesAmerican Continentalism and the Pursuit of Asian Commerce, 1845-1910c_helaliNo ratings yet

- Francisco Xavier ChavesDocument3 pagesFrancisco Xavier Chavesdonald_jennings_1No ratings yet

- Geronimo EssayDocument2 pagesGeronimo EssaywhysignupagainNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Westward ExpansionDocument4 pagesThe Impact of Westward Expansionapi-445112426No ratings yet

- Part IX Video Quiz 1 Fur Trade and The Transcontinental Railroad Jack Stauber-1Document4 pagesPart IX Video Quiz 1 Fur Trade and The Transcontinental Railroad Jack Stauber-1jack stauberNo ratings yet

- Hell Put to Shame: The 1921 Murder Farm Massacre and the Horror of America's Second SlaveryFrom EverandHell Put to Shame: The 1921 Murder Farm Massacre and the Horror of America's Second SlaveryRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Russia Hoax: The Illicit Scheme to Clear Hillary Clinton and Frame Donald TrumpFrom EverandThe Russia Hoax: The Illicit Scheme to Clear Hillary Clinton and Frame Donald TrumpRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (11)

- An Unfinished Love Story: A Personal History of the 1960sFrom EverandAn Unfinished Love Story: A Personal History of the 1960sRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Age of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the PresentFrom EverandAge of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the PresentRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)

- Hunting Eichmann: How a Band of Survivors and a Young Spy Agency Chased Down the World's Most Notorious NaziFrom EverandHunting Eichmann: How a Band of Survivors and a Young Spy Agency Chased Down the World's Most Notorious NaziRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (157)