Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Short Book Reviews

Uploaded by

wuk38Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Short Book Reviews

Uploaded by

wuk38Copyright:

Available Formats

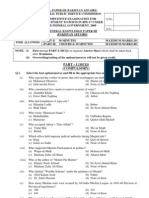

FURTHER READING

The editors have deemed the following titles to be of special interest for their important contributions to the academic literature on international affairs.

TO L I V E OR tO P ER ISH FOR EV ER : TWO TUMU ltUOUS YEA RS I N PA K IStA N

Nicholas Schmidle (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 2009), 272 pages. In March 2007, Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf sacked Chief Justice Iftikhar Mohammad Chaudhry as a result of the latters refusal to endorse a renewal of Musharrafs presidency. Chaudhrys dismissal exposed Pakistani civil societys growing distrust of Musharrafs rule, moving the nation to the verge of instability. American journalist Nicholas Schmidle was in Karachi in May 2007, when the pro-Musharraf Muttahida Quami Movement staged a rally on the same day Chaudhry was to address a gathering of lawyers in the city. He witnessed riots that quickly spiraled into ethnic strifethe gathering was a microcosm of a nation plagued by ethnic tensions among its Baluchis, Pashtuns, Punjabis and Sindhis. Schmidle posits that the failure of the state security apparatus to quell the violence in Karachi

was a deliberate attempt by Musharrafs regime to further destabilize an ethnically-divided nation, thereby rebuffing any viable opposition. Schmidles interviews with Islamist militants and political leaders in Swat and Waziristan reveal the complexity of changing alliances between Pakistani Islamist militants and the Afghan Taliban. Schmidle learned that many terrorist attacks carried out by Islamist militants are a way for feuding tribes to settle old scores that have lasted decades, and are not necessarily part of a broader political Islamist agenda. Furthermore, Schmidle implies that viewing a disparate group of Islamist militants as a monolith is problematic. After being deported from Pakistan in January 2008, Schmidle returned seven months later on the eve of Musharrafs resignation and the assumption of the presidency by Asif Ali Zardari, Benazir Bhuttos widower. Shortly after his return to Pakistan, Schmidle was tailed by Pakistans various intelligence agencies. Pakistans clandestine agencies remain a formidable force domestically and regionFALL/WINTER 2009 | 223

Journal of International Affairs, Fall/Winter 2009, Vol. 63, No. 1. The Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York

Further Reading ally, in both intelligence-gathering and intimidation of potential adversaries and unwelcome Westerners. These agencies are ultimately subsumed under an army that remains the dominant player in Pakistans political life. For fear of his personal safety, Schmidle quickly left Pakistan againa harrowing experience that signifies the Pakistani militarys resolve in preserving its powerful role within the state, illustrating that civilian-led governments have been of ephemeral importance during much of Pakistans sixty-two-year history. Schmidles book does a great job of capturing important nuances of Pakistani culture and politics, and his analysis is well done. He skillfully captures subtleties and details that most writers neglect or even get wrong. Waheed Ahmad Sheikh legacy of war in Afghanistan. According to Jalali, a former interior minister, both the Soviet intervention during the 1980s and the civil war in the 1990s involved internal armed factions and competing foreign states that crippled Afghan institutions. Jalali contends that, in order to rebuild and overcome this turbulent history, sustainable civil affairs assistance is needed in the rural areas of Afghanistan, such as building new schools or providing health services. In the economic sphere, Alastair McKechnie of the World Bank argues that microfinance, telecommunications, horticulture and mineral deposits are some of the areas that hold favorable prospects for short- to medium-term development. S. Frederick Starr of the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute emphasizes the role that regional integration can play in Afghanistans economic development, such as new energy links from Central Asia or routes to warm water ports. Cindy Fazey, a criminologist, concludes that a mainstreamed alternative livelihoods program, such as growing wheat or apricots instead of opium, in conjunction with vigorous law enforcement, is the most effective way to respond to Afghanistans drug dilemma. This is preferable to aerial spraying, for example, which could cause U.S. and NATO troops to lose support from local Afghan farmers. Skidmore College Dean Paula Newberg encourages readers not to neglect democratic development; if reconstruction becomes separated from it, Afghanistans polit-

B U I lDI NG

NEW A fGH A N IStA N

Robert Rotberg, ed. (Washington: Brookings Institution Press, 2007), 242 pages. In late 2006, Afghanistan saw a Taliban resurgence and, consequently, a deteriorating security situation. At that time, Robert Rotberg assembled nine contributors from Afghanistan, the United States and the United Kingdom to offer broad policy diagnoses for the various problems plaguing the country. In the first part of Building a New Afghanistan, the Afghan contributors, including Ali Jalali, Hekmat Karzai and Hedayat Amin-Arsala, consider the 224 | JOURNAL Of INTERNATIONAL AffAIRS

Further Reading ical trajectory will be seriously compromised. Judicial reform, she asserts, is what policymakers should focus on, since it strikes at the heart of both democratic development and material reconstruction in Afghanistan. Although the book touches on a broad array of issues, it offers few specifics on how to address some key challenges, such as corruption or reconciliation with the Taliban. Indeed, not a single contributor focuses on these issues, which are likely to be pivotal in shaping the future of Afghanistan. Readers interested in strategic-level initiatives in Afghanistan will enjoy Rotbergs book, but overall it covers too many topics without delving into the details necessary to execute policy initiatives. Jeffrey Klug the Taliban within the context of Afghanistans geography, noting the varied topographies that exist across eight climatic zones. From the bayonet peaks of the Hindu Kush to the arid deserts of Kandahar, historical, ethnic, linguistic and religious pluralities make Afghanistan both rich and complex. The authors establish that identities are rarely simple in Afghanistan. Each of the eight essays traces the rise of the Taliban from its inception in 1994, uniformly highlighting that the name Taliban as a static term fails to describe a dynamic movement. In Kandahar Province, the Taliban gained local support when Mullah Mohammad Omar and his band of madrassah students liberated a fleet of Pakistani transport trucks carrying high-value fuel from Central Asia from bandits and began guaranteeing safe transport between the border town of Spin Boldak and the provincial capital of Kandahar City. The Taliban as a single entity does not justifiably reflect its plurality of functions, from a regional security force to a dynamic cultural body of norms and influences that has solidified Pashtun fellowship and institutionalized fundamentalist Islam. Central to todays debate on American military expansion in one of the worlds most volatile regions, the breadth of Crews and Tarzis edited volume undermines the simplicity with which the AfPak strategy is framed as a regional palliative. The essays deeply probe those relationships and identities that belie the Taliban as a monolith and FALL/WINTER 2009 | 225

THE TA lIbA N A N D Of A fGH A N IStA N

tHE

C R ISIS

Robert D. Crews, Amin Tarzi, eds. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008), 430 pages. Robert Crews and Amin Tarzis The Taliban and the Crisis of Afghanistan consists of a compilation of eight essays from leading scholars of history, politics and society. It offers a composite perspective on the historical and political evolution of the Taliban in Afghanistan, focused on the internal political dynamics that underpin external observations of change. The book frames observation of

Further Reading uncover a human rationale that, though driven by fear, insecurity, ignorance and opportunism, must be understood and addressed if peace is to become a viable reality. Scott E. Hartley Partition, is inescapable. The book recalls without bias the systematic killings, kidnappings and rapes committed by both (soon-to-be) Pakistanis and Indians. Indeed, Khan says, the two nascent groups destroyed and shamed their own. She places much blame on the British for hastily dividing the land and failing to provide security throughout the transition, as well as on the South Asian middle class for strategically pushing party politics toward the edge of violent extremism. At only 251 pages, the book may be dismissed by scholars who demand volumes for one of the twentieth centurys most cataclysmic human rights disasters, but in covering an era of history so pertinent in todays politics, this book provides an efficient and insightful review. More importantly, as political tensions persist between India and Pakistan, Khans account offers a reconciliatory approach to an otherwise partisan and violent history. Kyle Henderson

THE G R EAt PA RtI tION

Yasmin Khan (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 251 pages. With only the eldest people of South Asia able to recall the subcontinents traumatic decolonization and division over sixty years ago, historians of the region work in a critical and shrinking window of time. Though academics have gained greater freedom to discuss events, they are tragically missing out on the opportunity to record them. Yasmin Khans recent contribution, The Great Partition, takes advantage of this newfound latitude to discuss the division of India and Pakistan. It begins just before the end of the British Raj and moves through World War II. The war, Khan argues, provided the suitable conditions for a turbulent transition. At first, the book alternates between a political history and a history of the poor masses, but the final 150 pages read as one long, sweeping description of massive violence and forced migration among the lower and middle classes. Analytical interjections and colorful anecdotes help to diversify the text, but the misery of the times, as wonderfully described by The Great 226 | JOURNAL Of INTERNATIONAL AffAIRS

I N tHE G R AV EyA R D Of E MpI R ES : A MER IcAS WA R A fGH A N IStA N

IN

Seth G. Jones (New York: W.W. Norton & Co. 2009), 352 pages. For many, the history of Afghanistan symbolizes the failure of foreign intervention. In Seth Jones In The Graveyard of Empires, however, the RAND consultant frames foreign intervention in

Further Reading terms of possibility rather than inevitable defeat. Jones regards the recent insurgency as a direct result of the governments inability to improve life in rural areas where local Afghans, left in a political vacuum, were persuaded or coerced to support militants. The initial determination of the United States to steer clear of the entanglements of nation building added to this shortcoming. Drawing an important lesson from the Soviet experience, Jones argues that garnering local support within Afghan clans and sub-clans is indispensable to the success of the current NATO mission. Decoupling the drug trade from politics, while maintaining a balance with powerful political figures who may be involved, is another major task. Jones also details the crucial importance of regional politics. While today Al Qaeda leaders based in Pakistan support the Taliban in opposition to the apostate Hamid Karzai regime, the government of Pakistan also previously supported the Taliban in a delicate game of regional politics aimed at installing a malleable government in Kabul. The extent to which this has stopped is debatable. The author attempts to construct an underlying connection between failed incursions in Afghanistan throughout history. Though it is difficult to verify the linkages between events separated by centuries or millennia presented in the book, the author effectively portrays a rugged and unrelenting environment which has transferred attributes to its peoples and as such created a particularly unwelcoming setting for both past conquest and current Western development approaches. Jones contrasts this image with the fact that despite turmoil, Afghanistan endures as it has for a very long time. He concludes that the aim of existing operations should be security and the prospect of easing the harshness of life in Afghanistan. This will not be achieved unless policymakers learn from the previous empires whose efforts died there. Dacia McPherson

THE D U El : PA K IStA N ON tHE F lIGHt PAtH Of A MER IcA N POW ER

Tariq Ali (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2008), 304 pages. Tariq Alis book, The Duel: Pakistan on the Flight Path of American Power, comes at a timely moment given the current debate on Pakistan and its many potential futures. In it, Ali provides a historical overview of Pakistans recurrent oscillation between incompetent civilian administrations and military dictatorships which, in combination with the business elite, have come to represent the countrys entrenched interests. This trio has consistently hijacked the levers of power across the countrys various decision-making institutions for private gain. While not a new contention, Ali provides evidence against some popular myths that policymakers, particularly FALL/WINTER 2009 | 227

Further Reading in the United States, would do well to consider. In particular, he notes the Wests misconception that the population is predominantly composed of raving extremists, and that it is these extremists who will hijack the countrys nuclear capability. Ali is also right in saying that U.S. foreign policy in Pakistan has consistently and continuously impeded the organic development of democracy in the country. An example is the extent to which the army has been strengthened vis--vis other decision-making institutions, largely thanks to bilateral U.S. military aid. His policy prescriptions are not particularly innovative including economic reform and the social empowerment of women. For those new to the subject who desire a concise overview of Pakistani history since independence, this book should suffice. Keener readers eager for a more detailed, nuanced and substantive analysis, however, would do well to look elsewhere. Mujtaba Rahman bold, robust and historical analysis, she tackles this issue with a considerable degree of success. One distinct aspect of her book is the attention given to the differences inherent within several distinct sects of Islam. She bluntly reminds Muslims that they should engage in collective introspection rather than externalizing all of their grievances.There is nothing new about this line of thought. What makes Bhuttos work refreshing is that someone of her caliber is courageous enough to address it from a point of knowledge as opposed to ignorance. In this book, she has gone the extra mile in debunking some of the long held perceptions that the crisis within the Muslim Ummah began with the West. She illustrates instances in which intraMuslim conflicts have wreaked more havoc than is readily acknowledged by many Muslims. Further, Bhutto succeeds in correcting the misinformation that Islam is a monolithic system that is immune to change. In her book she illustrates that there are various schools of thought and diverse ways of looking at issues within Islam. The books weakness emerges, however, when she turns to her own country of Pakistan. While there are elements of truth in some points she makes, in the end she comes off rather pompous and grandiose. She primes herself as the redeemer of Pakistananybody who opposes her or her fathers legacy is seen as the enemy of the Pakistani people. At this point, the book degenerates into a propaganda campaign for the Pakistani

R EcONcI lI AtION : I Sl A M , D EMOcR Acy, A N D tHE WESt

Benazir Bhutto (New York: HarperCollins, 2008), 352 pages. Benazir Bhuttos Reconciliation, Islam, Democracy, and the West is a useful addition to the growing literature that addresses the congruence, or lack thereof, of democracy and Islam. In a 228 | JOURNAL Of INTERNATIONAL AffAIRS

Further Reading Peoples Party and herself. Her enlightening analysis of Islam and democracy would have been better off without such grandiose personalization. Abdullahi Boru the book, she eloquently argues that the failure to stop the money flow to terrorist networks from this illegal trade is the single greatest failure in the Bush administrations global war on terror. Indeed, Peters presents a compelling case when she argues, This war isnt about ideology or religion. Its about creating a new economy for Afghanistanand breaking the cycle of violence and extremism that has gripped the region for decades. While her policy suggestions are not strong, Peters background research and fast-paced writing style are admirable, making this a must-read for anyone interested in the region and also an important resource for the Obama administration as it rewrites the script for U.S. engagement in Afghanistan. Gerri Pozez

S EEDS Of TER ROR : HOW H EROI N IS B A N K ROllI NG TA lIbA N A N D A l QA EDA

tHE

Gretchen Peters (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2009), 320 pages. In Seeds of Terror, journalist Gretchen Peters gives readers an in-depth look at all sides of the heroin trade in Afghanistan and Pakistan. The book explores the multifaceted issues surrounding this multibillion dollar illegal industry. Through exhaustive research that includes firsthand interviews, over a decade of travel and exclusive previews of classified documents, Peters attempts to answer many interlinked questions. For example: Who is benefiting from this drug trade: the Taliban, Al Qaeda or the U.S.-backed Afghan government? When and how did this rampant trade take hold in these volatile areas? Where is the money from this trade going? How might it affect U.S. security? Peters builds a solid case for her argument that narco-traffickers, terrorist groups and other related international criminals are in fact the new axis of evil. In this battle, Afghanistan is the main front for a revitalized Taliban dependent on opium crops for 70 percent of its funds. Throughout

D EScEN t I N tO C H AOS : THE U N I tED StAtES A N D tHE FA I lU R E Of N AtION B U I lDI NG I N PA K IStA N , A fGH A N IStA N , A N D C EN tR A l A SI A

Ahmed Rashid (New York: Viking Adult, 2008), 484 pages. As the Obama administration has refocused attention from Iraq to the upsurge of violence in Afghanistan, regional experts, like Pakistani journalist Ahmed Rashid, have been increasingly indispensable. Known for his prescience in alerting the public about the dangers of rising Islamist extremism FALL/WINTER 2009 | 229

Further Reading before September 11th, Rashids latest book examines the consequences of U.S. policies in Afghanistan and Pakistan after 9/11. In Descent into Chaos, Rashid asserts that persistent U.S. inattention to Afghanistan and Pakistan following the 2003 invasion of Iraq allowed for the Talibans return to Afghanistan and a re-solidification of its influence on both sides of the Durand Line. Instead of turning westward, he argues, the United States should have completed its mission and focused on building the institutional capacity and economy of the nascent Afghan state. He is highly critical of the U.S. approach to nationbuilding in Afghanistan, in particular its partnerships with warlords and relationship with the Pakistani state and military. Rashid ends the book with a note of pessimism about deteriorating conditions in Pakistan and Afghanistan and prospects for stability. Since the books 2008 publication, however, there are newly elected heads of state in Pakistan and the United States. This has caused attitudes in both countries to place renewed emphasis on eradicating the Taliban and Al Qaeda. Though some of Rashids recommendations now seem dated, many others demonstrate the insight of his earlier works, including the prescription to view Afghanistan and Pakistan holistically, which the Obama administration has done in naming a special advisor for AfPak. Rashid also advises that the United States and its NATO allies 230 | JOURNAL Of INTERNATIONAL AffAIRS reevaluate their goals and calls attention to the need for additional Afghan National Army and police funding. He cautions that, if ignored, Central Asia may become the next breeding ground for Islamist extremism. Given Rashids record, warnings like this should not be disregarded. Sonia Luthra

A ftER tHE TA lIbA N : L I fE A N D S EcU R I ty I N R U R A l A fGH A N IStA N

Neamatollah Nojumi, Dyan Mazurana, Elizabeth Stites (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2009), 309 pages. While talk of troop levels and the greater geopolitical game consume much of the current assessment of Afghanistan, After the Taliban uncovers the challenges to basic human security among the countrys rural population, a potentially crucial issue for the regions future. The book is a result of the work of research scholars and academics from Tufts University and George Mason University who conducted field work in 2003 and 2004 focusing on Afghanistans Badghis, Balkh, Herat, Kabul, Kandahar and Nangarhar provinces. The focus of the book is on security, livelihoods and various systems of justice in Afghanistan. The writers tease out various threads of development that, woven together, could support a strong society if properly addressed: health care, civil society, education, family

Further Reading structure and economic development. Though Nojumi et al. offer few surprises regarding the problems faced by rural Afghans, the authors explore lesser known aspects of the society. They then effectively assess how a variety of social factors have fluctuated, for better and for worse, after the fall of the Taliban. One example is the practice of badal, in which women are exchanged in marriage between families to settle disputes. The continuance of such practices indicates the weakness of the judicial system. This section proves to be the most interesting, as it highlights how authorities blatantly abuse power and offer no recourse to those wronged. It notes the importance of building capacity, especially among women, to ensure that people feel confident in bringing cases to court and seeking justice. Indeed, as the book unfolds, the negative impact of staggering gender inequality becomes evident. Whether it is inadequate access to medical attention or the distance a girl must travel to reach school, it becomes clear that gender inequality will impede Afghanistans stability and success in the long run. At times the prose gets bogged down with numbers and repetitive statements. Further, the author fails to focus on the potential role of an independent and robust media to foster social change in the region. Despite such shortcomings, this book serves as a vital resource to those who have an academic interest in Afghanistan or are involved in policymaking in the country. Rohina Phadnis

WOMEN Of A fGH A N IStA N tHE P OSt -TA lIbA N E R A

IN

Rosemarie Skaine (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., 2008), 193 pages. Rosemarie Skaines Women of Afghanistan in the Post-Taliban Era attempts to evaluate changes in the quality of life for Afghanistans women since the fall of the Taliban. Despite the books dense documentation from NGOs, the UN and government officials, the language and structure of the book is very accessible. While the author did not live in or visit Afghanistan, the book still gives the reader a compelling view on an important issue. Skaines optimism regarding the future of women in Afghanistan mainly originates from her discussions with women who are currently high-level government officials and who secured their positions as a result of the U.S. invasion. While this is a very important trend, the majority of these success stories concern women who were educated and/or lived in the West for some time. Considering that Afghanistans poverty prevents all but a few very elite members of the society from sending their children abroad, one might wonder if these women truly represent change for Afghan women more generally. Additional evidence seems encouraging at first glance, but Skaine utilizes incomplete measures such as enrollment in school. Such an indicator may have little value considering that most of those schools have no teachers, desks FALL/WINTER 2009 | 231

Further Reading or buildings. Skaine highlights this by noting various testimoniesone of the more interesting of which describes how Afghanistans main university did not have a single map of the world for long periods of time. This highlights the reality that the value of attending school may be limited by the schools capacity to give an appropriate education to its students. While Skaine offers this anecdotal evidence, she does not integrate it with her quantitative measures and thus fails to consider it in her final conclusions. The war in Afghanistan is still ongoing and every improvement in the lives of Afghans and especially Afghan women is extremely fragile. Estimating the meaningful changes in a country that is in a state of war when the lives of its citizens are in constant flux is a complex challenge that perhaps cannot be adequately measured at present. Irina Gambs extended to running for high office in Afghanistanhe was a presidential candidate in the 2009 elections. Ghani and Lockharts work designing development projects with the UN, World Bank and Afghan government later formed the foundation for a grand state-building framework. Their book, Fixing Failed States, is a critical and programmatic account developed around the ups an downs of this process. The idea of failed states is not new to the academic and policy communities. Prior discussion has highlighted the need to increase local governments ability to deliver services rather than rely on aid agencies to do so. Ghani and Lockhart, however, attempt to establish a conceptual and systemic account instead of simply offering strict policy prescriptions. The mechanistic sound of the term fixing failed states may not be liked by some academics, but doing so allows the authors to adopt a functionalistic approach in understanding the state in practice and facilitates illustration by actual historical examples. The book is written based on the experience of once-failed states that have managed to reverse history by reestablishing themselves. The examples are geographically diverse, from Singapore to Spain to even the American South. While the book may seem pessimistic by noting that failed states are actually more numerous than commonly believed, the main message of the book is positive: failed states can be fixed. Khisraw Amini

F I X I NG FA I lED StAtES

Ashraf Ghani, Clare Lockhart (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 254 pages. While many of the international practitioners who worked in Afghanistan in recent years have profited from their experiences by writing bestsellers, others, such as Ashraf Ghani and Clare Lockhart, are now engaged with more holistic questions of international development. Ghanis commitment has even

232 | JOURNAL Of INTERNATIONAL AffAIRS

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Mishima Special Skills GuideDocument14 pagesMishima Special Skills Guidehorned_god100% (1)

- Relic Nemesis RulebookDocument20 pagesRelic Nemesis RulebookJose Manuel Mujica SantanaNo ratings yet

- Dark Age Infantry Slog Tactics and RatingsDocument11 pagesDark Age Infantry Slog Tactics and RatingsBeagle75No ratings yet

- John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and the First Barbary WarDocument15 pagesJohn Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and the First Barbary WarWasi ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Final Semi-Detailed LP (Literature)Document4 pagesFinal Semi-Detailed LP (Literature)Lielane Varela100% (1)

- Sonia Khan Was The Bofors ThiefDocument5 pagesSonia Khan Was The Bofors Thiefmurky167% (3)

- Education in and For ConflictDocument66 pagesEducation in and For ConflictDaisy100% (2)

- Pakistan Engineering Council: Application Form For Registered EngineerDocument7 pagesPakistan Engineering Council: Application Form For Registered EngineerSufian AhmadNo ratings yet

- Four Principles of ShirkDocument57 pagesFour Principles of Shirkwuk38No ratings yet

- SQA Plan TemplateDocument106 pagesSQA Plan TemplatedtsharpieNo ratings yet

- Shan e Rasool Sahaba Karam Aur Sahaba Karam K Aqyied Ki Roshni MainDocument226 pagesShan e Rasool Sahaba Karam Aur Sahaba Karam K Aqyied Ki Roshni Mainwuk38No ratings yet

- Premium Microsoft 70-680 574q Exam PDF Dumps For Free Share 351-400-LibreDocument40 pagesPremium Microsoft 70-680 574q Exam PDF Dumps For Free Share 351-400-Librewuk38No ratings yet

- Premium Microsoft 70-680 574q Exam PDF Dumps For Free Share 151-200-LibreDocument29 pagesPremium Microsoft 70-680 574q Exam PDF Dumps For Free Share 151-200-Librewuk38No ratings yet

- Premium Microsoft 70-680 574q Exam PDF Dumps For Free Share 251-300-LibreDocument31 pagesPremium Microsoft 70-680 574q Exam PDF Dumps For Free Share 251-300-Librewuk38No ratings yet

- Premium Microsoft 70-680 574q Exam PDF Dumps For Free Share 201-250-LibreDocument41 pagesPremium Microsoft 70-680 574q Exam PDF Dumps For Free Share 201-250-Librewuk38No ratings yet

- Annual Leave Schedule For The Year 2012 (Final)Document2 pagesAnnual Leave Schedule For The Year 2012 (Final)wuk38No ratings yet

- Premium Microsoft 70-680 574q Exam PDF Dumps For Free Share 351-400-LibreDocument40 pagesPremium Microsoft 70-680 574q Exam PDF Dumps For Free Share 351-400-Librewuk38No ratings yet

- Mian Ejaz PDFDocument1 pageMian Ejaz PDFwuk38No ratings yet

- Premium Microsoft 70-680 574q Exam PDF Dumps For Free Share 101-150-LibreDocument18 pagesPremium Microsoft 70-680 574q Exam PDF Dumps For Free Share 101-150-Librewuk380% (1)

- S. No System (UPS/ Charger) Model No Station Sub-Location Gutor Serial NoDocument2 pagesS. No System (UPS/ Charger) Model No Station Sub-Location Gutor Serial Nowuk38No ratings yet

- Direct Overt U.S. Aid Appropriations For and Military Reimbursements To Pakistan, FY2002-FY2014Document1 pageDirect Overt U.S. Aid Appropriations For and Military Reimbursements To Pakistan, FY2002-FY2014wuk38No ratings yet

- Israel: Background and U.S. Relations: Jim ZanottiDocument47 pagesIsrael: Background and U.S. Relations: Jim Zanottiwuk38No ratings yet

- Direct Overt U.S. Aid Appropriations For and Military Reimbursements To Pakistan, FY2002-FY2014Document1 pageDirect Overt U.S. Aid Appropriations For and Military Reimbursements To Pakistan, FY2002-FY2014wuk38No ratings yet

- Higher Algebra - Hall & KnightDocument593 pagesHigher Algebra - Hall & KnightRam Gollamudi100% (2)

- US-Pakistan Relations 1958-69 Impact on South AsiaDocument12 pagesUS-Pakistan Relations 1958-69 Impact on South Asiawuk38100% (1)

- GK Iii09Document2 pagesGK Iii09Iman AliNo ratings yet

- Significance of Non-Alignment MovementDocument5 pagesSignificance of Non-Alignment Movementwuk38No ratings yet

- Is Nam Relevant TodayDocument3 pagesIs Nam Relevant Todaywuk38No ratings yet

- Higher Algebra - Hall & KnightDocument593 pagesHigher Algebra - Hall & KnightRam Gollamudi100% (2)

- Higher Algebra - Hall & KnightDocument593 pagesHigher Algebra - Hall & KnightRam Gollamudi100% (2)

- Major U.S. Arms Sales and Grants To Pakistan Since 2001Document1 pageMajor U.S. Arms Sales and Grants To Pakistan Since 2001wuk38No ratings yet

- Major Islamist Militant Groups in PakistanDocument1 pageMajor Islamist Militant Groups in Pakistanwuk38No ratings yet

- ABB Electric Motor Water CooledDocument147 pagesABB Electric Motor Water CooledMoustapha SeyeNo ratings yet

- Business and Society: Socially Responsive ManagementDocument11 pagesBusiness and Society: Socially Responsive Managementwuk38No ratings yet

- Charles Windham Family Group SheetDocument4 pagesCharles Windham Family Group Sheetapi-26011449No ratings yet

- Annotated BibliographyDocument8 pagesAnnotated BibliographynicholasnazzaroNo ratings yet

- HTTP CGSC - Contentdm.oclc - Org Cgi-Bin Showfile - Exe CISOROOT p4013coll2&CISOPTR 2503&filename 2554Document231 pagesHTTP CGSC - Contentdm.oclc - Org Cgi-Bin Showfile - Exe CISOROOT p4013coll2&CISOPTR 2503&filename 2554Luciano BurgalassiNo ratings yet

- Workers and Farmers Solidarity League of BurmaDocument2 pagesWorkers and Farmers Solidarity League of BurmaPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- Channel Management - 14Document19 pagesChannel Management - 14dua khanNo ratings yet

- Nama Sahabat NabiDocument2 pagesNama Sahabat NabiKayla BilbinaNo ratings yet

- Anti-Aircraft Journal - Dec 1951Document56 pagesAnti-Aircraft Journal - Dec 1951CAP History Library100% (1)

- gpujpthjp rk;kd; - Notice of Hearing in a Summary SuitDocument25 pagesgpujpthjp rk;kd; - Notice of Hearing in a Summary Suitsharanmit6630No ratings yet

- Freebitco in 10000 Script 1Document2 pagesFreebitco in 10000 Script 1fadli0% (1)

- Operation Iraqi Freedom1Document69 pagesOperation Iraqi Freedom1Alka Seltzer100% (2)

- A Land in Conflict On Myanmar's Western FrontierDocument160 pagesA Land in Conflict On Myanmar's Western FrontierInformer100% (1)

- The Decline of The Ottoman EmpireDocument6 pagesThe Decline of The Ottoman EmpireEmilypunkNo ratings yet

- References: BooksDocument7 pagesReferences: Booksudit prantoNo ratings yet

- Essays Muslim Union PerilsDocument2 pagesEssays Muslim Union PerilsKAZMI01No ratings yet

- The Global Islamic Resistance Call - Chapter 8, Sections 5 To 7 LIST of TARGETSDocument62 pagesThe Global Islamic Resistance Call - Chapter 8, Sections 5 To 7 LIST of TARGETSSuhail3015No ratings yet

- Index From Military Manpower, Armies and Warfare in South AsiaDocument22 pagesIndex From Military Manpower, Armies and Warfare in South AsiaPickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- Battle of SurabayaDocument5 pagesBattle of SurabayaIqbal Safirul BarqiNo ratings yet

- WO7Document24 pagesWO7DistractionManNo ratings yet

- Chinua Achebe BiographyDocument2 pagesChinua Achebe Biographyapi-248375504No ratings yet

- The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia Volume 2, The NineteenthDocument9 pagesThe Cambridge History of Southeast Asia Volume 2, The Nineteenthsergeeyv4No ratings yet

- Salem PoorDocument2 pagesSalem PoorwtlodgeNo ratings yet

- When The Ruler of The 7th House Is Retrograde at Birth, "The Other", The Partner and Everyone You Meet orDocument4 pagesWhen The Ruler of The 7th House Is Retrograde at Birth, "The Other", The Partner and Everyone You Meet orKrishna CHNo ratings yet

- Bullying in SchoolDocument30 pagesBullying in SchoolDimas Aji KuncoroNo ratings yet