Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Men of Freedom: A Review of T. H. Breen and Stephen Innes' "Myne Owne Ground"

Uploaded by

Senator FinkeOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Men of Freedom: A Review of T. H. Breen and Stephen Innes' "Myne Owne Ground"

Uploaded by

Senator FinkeCopyright:

Available Formats

Christopher Finke HIST 380 TR 11:00am 12:20pm

Finke 2 Breen, T.H. and Stephen Innes. Myne Owne Ground: Race and Freedom On Virginias Eastern Shore, 1640-1676. New York NY: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Myne Owne Ground presents to the reader with information, analysis, and a perspective that is much different from the mainstream. In the study of colonial America one will inevitably take notice of Virginia. However, it is more than likely that this observation will exclude Virginias Eastern Shore. A small geographical area composed of two (sometimes one) county, the Eastern Shores population remained small throughout the 17th century. Even so, these counties had a high percentage of Negro residents. These residents prove to be an exception to the oft thought scenario brought on by slavery. This work by T.H. Breen and Stephen Innes gives the audience a chance to understand the relationships that these blacks had and to show that Virginias Eastern Shore operated much differently than most would expect. The basis of freedom and social status were not based solely on race, as some would have you believe. Breen and Innes push the argument that the foundation of society (including freedoms) was based on property ownership rather than race. The authors take a topical approach to their argument. They begin by giving the story of the most successful free black of Virginias Eastern Shore: Anthony Johnson. Johnson appeared as a servant in the 1625 census, which likely means that he was brought as a lifelong slave.(8) By 1651 he had more than 250 acres of land, livestock, a wife, children, and all the disputes to go with them. (11) Disputes over tax status, the ownership of cattle, and the status of another black man give the local courts record of some of what happened to Johnson over the years. (12-3) In the mid-1660s, Johnson and his family, which could rightly be called a clan by this point, moved out of Virginia and into Maryland. The Johnson narrative is a crucial part of this

Finke 3 monograph because it also acts as an outline for the remainder of the work. The Johnson story outlines the questions of physical relationship, socio-economic relationship, and cultural/interracial relationship that Breen and Innes seek to answer. The authors then go on to address the factors which both effect and are affected by race. Breen and Innes discuss the question of the legal status of blacks in Virginia. In this section they also deliberate, and overcome, three assumptions that are rarely addressed by other authors; the 1860s version of slavery does not necessarily stem directly from the 1660s, race is not the defining reason for the way a person lives, the research into the system of slavery does not equate to research into the lives of individual slaves. (21) The authors then show the reader under what context men like Anthony Johnson lived. Finally, Myne Owne Ground describes the story of free blacks on Virginias Eastern Shoreand show one what foundation colonial freedoms were built. The arguments made by Breen and Innes, though counter to common thinking, are supported well enough to bring the audience to a place where they can begin overturning the misconceptions within their mind. The authors use many specific examples with which they build up their own argument or tearing down well accepted falsehoods. Breen and Innes have no qualms when they make an example of one of the most respected works on American slavery, White Over Black by Winthrop Jordan. One of the claims made in this work is that laws could be extrapolated to represent the ideas of the time and people. (24) Myne Owne Ground shows how limited the usefulness of this idea is. Breen and Innes explain how this idea snowballed when dealing with the ownership of firearms. Carl Deglers analysis of a colonial Virginia statute that regulated blacks ownership of weapons claimed that blacks were singled out and discriminated against. Jordan came back to

Finke 4 claim that the statute was even more significant than Degler thought. (25) The law continued to grow in importance when Degler again transformed the 1640 act from proscriptive legislation into a description of actual social practice. (25) Breen and Innes summarize this slippery slope by stating that we have movedfrom a single, somewhat ambiguous case of racial discrimination to a general statement about white attitudes toward all blacks and, finally, to a complete disarmament of the colonys black population. (25-6) This type of analysis exists throughout the monograph and supports every major theme that the duo writes about. The strong examination is certainly a powerful strength, but weaknesses exist too. The book has a limited scope, geographically, politically, and economically. Virginias Eastern Shore was by no means the largest area, and thus could not support a large population, nor was it excessively fertile, making it difficult to amass a large tobacco crop. These limitations restricted the Eastern Shores political influence, and thus its ability to guide the decision making of the colonial government. This limitation of scope also makes it difficult to extrapolate if the situation on Virginias Eastern Shore means anything or has any bearing on other areas. The vast plantations of the Western Shore, the cities of New England, and the lack of early settlement of the Carolinas proves a marked difference that cannot be overcome without much evidence. The work also fails to address much of what would happen on a day to day basis. Even the authors as they admit that this analysis seems incomplete. (17) Breen and Innes know that pieces of the puzzle remain unaccounted for since there is little to no first hand writings about the common events. (17) While the court records that are used give the reader much information and even more can be inferred from them, they do not tell exactly how people lived and cannot give the reader insight into the normal lives lived by the free blacks of the Eastern Shore. Sadly,

Finke 5 these records just do not exist, therefore, this lack of records cannot truly be held against the authors. Myne Owne Ground is not without its strengths though. Along with the strong analysis, Breen and Innes excel at using available information to make claims about Virginias Eastern Shore. Court records may not give the reader the day-to-day, but they do give an idea of the bigger events. Courtship, marriage, and the growth of families can be examined through licenses, tithables lists, and child support records. Economic situations dealing with land or livestock gives the reader a comparative value with which they can better understand the finances of the time. This small volume of information also allows Breen and Innes the convenience of thoroughness without contexting the information to death. The limited scope is both the biggest weakness and the biggest strength. It allows the authors to delve as deeply as they can into the goings on of the area. They could examine four or five major planters, being as there were not many major planters to begin with, and the reader will get a good idea of what went on. In the end, Myne Owne Ground provides strong proofs for the claim that property was a more important social identifier than was race. The interactions between free blacks, local gentry, nongentry whites, and enslaved blacks do not show that race was invisible. They do, however, show that a free black that owned property could hold sway over a poor white in the court of law as well as in the court of public opinion. Breen and Inness work masterfully shows how common ideas of slavery were not always so, the institution of slavery and the discrimination against blacks progressed in fits and spurts. This non-linear progression, though contrary to oft believed theories, is thoroughly supported by this monograph. Myne Owne Ground has been in print for more than 25 years and, due to the enormous effect it can have on readers, will remain an influential work on American slavery for years to come

You might also like

- Pornography: Five Deadly Consequences On HumansDocument191 pagesPornography: Five Deadly Consequences On Humansv00s100% (1)

- The Slums Reaction Paper PDFDocument2 pagesThe Slums Reaction Paper PDFharperboy0921100% (2)

- Security & Safety Hand BookDocument110 pagesSecurity & Safety Hand BookIts Mind's Eye100% (22)

- Letters From A War Zone - Andrea Dworkin PDFDocument338 pagesLetters From A War Zone - Andrea Dworkin PDFТатьяна Керим-ЗадеNo ratings yet

- The Backup Boyfriend:GirlfriendDocument3 pagesThe Backup Boyfriend:Girlfriendcreo williamsNo ratings yet

- The Neoliberalization of FootballDocument25 pagesThe Neoliberalization of FootballSam DubalNo ratings yet

- Winning of The West Vol. 1Document152 pagesWinning of The West Vol. 1lola larvale100% (1)

- Economics Notes Class 11 All in OneDocument0 pagesEconomics Notes Class 11 All in Onewww.bhawesh.com.np85% (46)

- People Vs BelloDocument1 pagePeople Vs Bellojason caballeroNo ratings yet

- Phillips, J., Third CrusadeDocument23 pagesPhillips, J., Third CrusadeAmiNo ratings yet

- Fear of A Black RepublicDocument378 pagesFear of A Black RepublicEl Deivid100% (1)

- Integrating Positivist and Interpretive Approaches To Organizational ResearchDocument25 pagesIntegrating Positivist and Interpretive Approaches To Organizational ResearchH lynneNo ratings yet

- Appiah, The Lies That BindDocument16 pagesAppiah, The Lies That BindMaria Paula Suarez100% (1)

- Peter H. Lindert-Growing Public - Volume 1, The Story - Social Spending and Economic Growth Since The Eighteenth Century (2004)Document397 pagesPeter H. Lindert-Growing Public - Volume 1, The Story - Social Spending and Economic Growth Since The Eighteenth Century (2004)Rogelio Rodríguez Malja50% (2)

- Youth Participation in GovernanceDocument57 pagesYouth Participation in GovernanceRamon T. Ayco100% (15)

- The Nativist Lobby: Three Faces of IntoleranceDocument21 pagesThe Nativist Lobby: Three Faces of IntoleranceBento Spinoza100% (1)

- How To Be Like Hank Moody From CalifornicationDocument9 pagesHow To Be Like Hank Moody From CalifornicationJayne Spencer100% (1)

- Mayhew - Electoral RealignmentDocument20 pagesMayhew - Electoral RealignmentJairo PimentelNo ratings yet

- Why Iam Historical Institutionalist SkocpolDocument5 pagesWhy Iam Historical Institutionalist SkocpolAna Paula GaldeanoNo ratings yet

- Tobin - Commercial Banks As Creators of MoneyDocument12 pagesTobin - Commercial Banks As Creators of MoneyJung ZorndikeNo ratings yet

- Globalization Technology Philosophy PDFDocument258 pagesGlobalization Technology Philosophy PDFunschuldNo ratings yet

- Academia Effective Altruism and Global JusticeStanford GabrielDocument25 pagesAcademia Effective Altruism and Global JusticeStanford GabrielSanja P.No ratings yet

- Karen Hudes Dropped The J Word On Russia TodayDocument6 pagesKaren Hudes Dropped The J Word On Russia TodaybetancurNo ratings yet

- Guendelsberger Is The Author Of: On The Clock: What Low-Wage Work Did To Me and How It Drives America InsaneDocument1 pageGuendelsberger Is The Author Of: On The Clock: What Low-Wage Work Did To Me and How It Drives America InsaneSuraiya SuroveNo ratings yet

- "Ghettoside" Excerpt.Document6 pages"Ghettoside" Excerpt.Erik LorenzsonnNo ratings yet

- Interpersonal Communications Chapter 12Document5 pagesInterpersonal Communications Chapter 12randomscribduser2012No ratings yet

- Private Truths, Public Lies. The Social Consequences of Preference Falsification by Timur Kuran (Z-Lib - Org) - 5Document39 pagesPrivate Truths, Public Lies. The Social Consequences of Preference Falsification by Timur Kuran (Z-Lib - Org) - 5Henrique Freitas PereiraNo ratings yet

- Global Populism Globalisation Paper TCMDocument12 pagesGlobal Populism Globalisation Paper TCMHafiz KamranNo ratings yet

- Conversaciones Conmigo MismoDocument53 pagesConversaciones Conmigo MismoJhony Sanchez100% (2)

- Mccloskey Donald Now Deirdre The Rhetoric of EconomicsDocument122 pagesMccloskey Donald Now Deirdre The Rhetoric of EconomicsShamika NelsonNo ratings yet

- Robert W McChesney, John Nichols - People Get Ready - The Fight Against A Jobless Economy and A Citizenless Democracy (2016, Nation Books) PDFDocument369 pagesRobert W McChesney, John Nichols - People Get Ready - The Fight Against A Jobless Economy and A Citizenless Democracy (2016, Nation Books) PDFCarolina BagattolliNo ratings yet

- International Communication - Daya Kishan Thussu (2002)Document353 pagesInternational Communication - Daya Kishan Thussu (2002)Abhas Dharananda RajopadhyayaNo ratings yet

- Frank H. Knight-Intelligence and Democratic Action-Harvard University Press (1960)Document184 pagesFrank H. Knight-Intelligence and Democratic Action-Harvard University Press (1960)Guilherme MachadoNo ratings yet

- 1976 - Bell, Daniel - The Coming of The Post-Industrial SocietyDocument7 pages1976 - Bell, Daniel - The Coming of The Post-Industrial SocietyIrving RiveroNo ratings yet

- Georgism PDFDocument29 pagesGeorgism PDFkazuperNo ratings yet

- Market Failure Tyler CowanDocument34 pagesMarket Failure Tyler CowanalexpetemarxNo ratings yet

- John L. McKnight - A Guide For Government OfficialDocument3 pagesJohn L. McKnight - A Guide For Government Officialsaufi_mahfuz100% (1)

- Global and Historical Perspectives On InnovationDocument11 pagesGlobal and Historical Perspectives On Innovationogangurel100% (3)

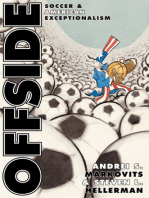

- Offside: Soccer and American ExceptionalismFrom EverandOffside: Soccer and American ExceptionalismRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (5)

- KeatingPaperDocument34 pagesKeatingPaperMelanie Henley HeynNo ratings yet

- Do Economists Make Markets?: On the Performativity of EconomicsFrom EverandDo Economists Make Markets?: On the Performativity of EconomicsRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (2)

- Passmore - 100 Years PhilosophyDocument14 pagesPassmore - 100 Years Philosophyalfonsougarte0% (2)

- Engin Isin Citizenship in FluxDocument22 pagesEngin Isin Citizenship in FluxMert OzgenNo ratings yet

- The Preindustrial CityDocument9 pagesThe Preindustrial CityRadosveta KirovaNo ratings yet

- Ain-T I A Woman - Revisiting Intersectionality - Avtar Brah PDFDocument13 pagesAin-T I A Woman - Revisiting Intersectionality - Avtar Brah PDFViviane S. MartinhãoNo ratings yet

- Beard - Noble Dream PDFDocument15 pagesBeard - Noble Dream PDFDarek SikorskiNo ratings yet

- American Economic Review-Top 20 ArticlesDocument8 pagesAmerican Economic Review-Top 20 ArticlesClub de Finanzas Economía-UCV100% (1)

- Human Reactions To Rape Culture and Queer Performativity at Urban Dog Parks in Portland, OregonDocument21 pagesHuman Reactions To Rape Culture and Queer Performativity at Urban Dog Parks in Portland, OregonToronto Star100% (1)

- Staging The Nation's Rebirth: The Politics and Aesthetics of Performance in The Context of Fascist StudiesDocument32 pagesStaging The Nation's Rebirth: The Politics and Aesthetics of Performance in The Context of Fascist StudiesMarkoff ChaneyNo ratings yet

- Espaço Público e Cidade - MITCHELLDocument5 pagesEspaço Público e Cidade - MITCHELLCarlos BortoloNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Imagined Communities - and BenedDocument6 pagesThe Importance of Imagined Communities - and BenedAssej Mae Pascua villaNo ratings yet

- Dainess Maganda Cv-July 2021Document10 pagesDainess Maganda Cv-July 2021api-556449878No ratings yet

- Principia Politica PDFDocument41 pagesPrincipia Politica PDFC0UNDE100% (1)

- Israelpolitik: Regimes of Truth and The Clash of Definitions in The "Promised Land"Document20 pagesIsraelpolitik: Regimes of Truth and The Clash of Definitions in The "Promised Land"Brent CooperNo ratings yet

- The Little Mermaid's Silent Security Dilemma and The Absence of Gender in The Copenhagen SchoolDocument23 pagesThe Little Mermaid's Silent Security Dilemma and The Absence of Gender in The Copenhagen Schoolanna.weichselbraun5474No ratings yet

- Knapp 1924 The State Theory of MoneyDocument162 pagesKnapp 1924 The State Theory of Moneyalejandro100% (1)

- Tribe Legis Memo On SOPA 12-6-11 1Document23 pagesTribe Legis Memo On SOPA 12-6-11 1Marty Schwimmer100% (3)

- Cycle of American L 030045 MBP 3Document345 pagesCycle of American L 030045 MBP 3avid2chatNo ratings yet

- End of Capitalism As We Knew ItDocument12 pagesEnd of Capitalism As We Knew Itسارة حواسNo ratings yet

- Critical Crimin OlogiesDocument28 pagesCritical Crimin OlogiespurushotamNo ratings yet

- DALOZ, Jean-Pascal (2007) - Elite DistinctionDocument46 pagesDALOZ, Jean-Pascal (2007) - Elite DistinctionVinicius FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Theories of Distributive JusticeDocument8 pagesTheories of Distributive JusticeAnkit KumarNo ratings yet

- Professor Leslie McCall The Undeserving Rich American Beliefs About Inequality, Opportunity, and Redistribution (2013) PDFDocument320 pagesProfessor Leslie McCall The Undeserving Rich American Beliefs About Inequality, Opportunity, and Redistribution (2013) PDFpantellusNo ratings yet

- LefebvreDocument52 pagesLefebvreDinaSeptiNo ratings yet

- Crossley y Roberts - After HabermasDocument185 pagesCrossley y Roberts - After HabermasMatías Valderrama BarragánNo ratings yet

- Oxford Scholarship Online: Party/Politics: Horizons in Black Political ThoughtDocument24 pagesOxford Scholarship Online: Party/Politics: Horizons in Black Political ThoughtJuliana GóesNo ratings yet

- Order On AppealDocument2 pagesOrder On AppealAnn DwyerNo ratings yet

- Fans of the World, Unite!: A (Capitalist) Manifesto for Sports ConsumersFrom EverandFans of the World, Unite!: A (Capitalist) Manifesto for Sports ConsumersRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Interpersonal Comparison of Utility - RobbinsDocument8 pagesInterpersonal Comparison of Utility - RobbinsarterioNo ratings yet

- Name: Program & Year: TIME & DAY: 10:00-11:30AM TF Class ScheduleDocument4 pagesName: Program & Year: TIME & DAY: 10:00-11:30AM TF Class ScheduleFlorebel YagaoNo ratings yet

- Efféminés, Gigolos, and Msms in The Cyber-Networks, Coffeehouses, and "Secret Gardens" of Contemporary TunisDocument24 pagesEfféminés, Gigolos, and Msms in The Cyber-Networks, Coffeehouses, and "Secret Gardens" of Contemporary TunisAlice TallembergNo ratings yet

- SarvodayaDocument3 pagesSarvodayaSumit Roy SarkarNo ratings yet

- Child Marriage Should Be Banned: (Access On 10/5/2019 at 7:36 A.M.)Document3 pagesChild Marriage Should Be Banned: (Access On 10/5/2019 at 7:36 A.M.)Dewi SariNo ratings yet

- Solutions December 2010Document8 pagesSolutions December 2010armcorpcommNo ratings yet

- Social Darwinism and White Mans BurdenDocument1 pageSocial Darwinism and White Mans Burdenapi-302771208No ratings yet

- Philippines View On BeautyDocument20 pagesPhilippines View On BeautyMichelle Yvonne ClerigoNo ratings yet

- CDX Brgy60Document187 pagesCDX Brgy60maria apolonia mancaoNo ratings yet

- Stop and Frisk Letter To Mayor KenneyDocument2 pagesStop and Frisk Letter To Mayor KenneyWHYY NewsNo ratings yet

- The United Methodist Church Values School, Inc.: Palamis, Alaminos City, PangasinanDocument1 pageThe United Methodist Church Values School, Inc.: Palamis, Alaminos City, Pangasinanfennie ilinah molinaNo ratings yet

- The Migration Conference 2018 Book of Ab PDFDocument346 pagesThe Migration Conference 2018 Book of Ab PDFVivian Kosta0% (1)

- APUSH Chapter 11 OutlinesDocument6 pagesAPUSH Chapter 11 OutlinesClaudia HuoNo ratings yet

- Brainstorming: DiscriminationDocument10 pagesBrainstorming: DiscriminationRaajuHoolausNo ratings yet

- Alcoholics QuotesDocument4 pagesAlcoholics QuotesKate100% (1)

- Empathy Research DocumentDocument3 pagesEmpathy Research Documentapi-511980534No ratings yet

- PkscriptDocument1 pagePkscriptapi-287552055No ratings yet

- Womens Rights 1800s - NewsleaDocument3 pagesWomens Rights 1800s - Newsleaapi-503469785100% (1)

- Magnificence Critical EssayDocument2 pagesMagnificence Critical EssayMarc Castro100% (1)