Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Allegory of The Cave

Uploaded by

GnosticLuciferOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Allegory of The Cave

Uploaded by

GnosticLuciferCopyright:

Available Formats

Allegory of the Cave

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Plato's Allegory of the Cave by Jan Saenredam, according to Cornelis van Haarlem, 1604, Albertina, Vienna

Part of a series on

Plato

Plato from The School of Athens by Raphael, 1509

Early life Works Platonism Epistemology

Idealism / Realism Demiurge Transcendentals Form of the Good Third man argument Euthyphro dilemma

Theory of Forms

Five regimes

Philosopher king

Allegories and metaphors

Atlantis The cave The sun Ship of state Myth of Er The chariot

Ring of Gyges The divided line

Related articles

Commentaries Socratic problem Middle Platonism Neoplatonism

o

The Academy in Athens

and Christianity

Philosophy portal

The Allegory of the Cave (also known as the Analogy of the Cave, Plato's Cave or the Parable of the Cave) is presented by the Greek philosopher Plato in his work The Republic (514a-520a) to compare "...the effect of education and the lack of it on our nature". It is written as a dialogue between Plato's brother Glaucon and his mentor Socrates, narrated by the latter. The Allegory of the Cave is presented after the metaphor of the sun (508b509c) and the analogy of the divided line (509d513e). All three are characterized in relation to dialectic at the end of Book VII and VIII (531d 534e). Plato has Socrates describe a gathering of people who have lived chained to the wall of a cave all of their lives, facing a blank wall. The people watch shadows projected on the wall by things passing in front of a fire behind them, and begin to ascribe names to these shadows. According to Plato's Socrates, the shadows are as close as the prisoners get to viewing reality. He then explains how the philosopher is like a prisoner who is freed from the cave and comes to understand that the shadows on the wall do not make up reality at all, as he can perceive the true form of reality rather than the mere shadows seen by the prisoners.

The Allegory may be related to Plato's Theory of Forms, according to which the "Forms" (or "Ideas"), and not the material world of change known to us through sensation, possess the highest and most fundamental kind of reality. Only knowledge of the Forms constitutes real knowledge.[1] In addition, the Allegory of the Cave is an attempt to explain the philosopher's place in society: to attempt to enlighten the "prisoners." Plato's Phaedo contains similar imagery to that of the Allegory of the Cave; a philosopher recognizes that before philosophy, his soul was "a veritable prisoner fast bound within his body... and that instead of investigating reality by itself and in itself it is compelled to peer through the bars of its prison."[2]

Contents

1 Synopsis o 1.1 Imprisonment inside the Cave o 1.2 Leaving the Cave o 1.3 Return to the Cave o 1.4 Remarks on the Allegory 2 Influence 3 See also 4 References 5 External links

Synopsis

Imprisonment inside the Cave

Socrates begins by asking Glaucon to imagine a cave inhabited by prisoners who have been imprisoned since childhood in such a way that their legs and necks are fixed, such that they cannot move their heads and are thereby forced to gaze at a wall in front of them. (514a-b) Behind the prisoners is a fire, and between the fire and the prisoners is a raised walkway. Along this walkway is a low wall, behind which people walk carrying objects "...including figures of men and animals made of wood, stone and other materials." (514c-515a) In this way, the walking people are compared to puppeteers and the low wall to the screen over which puppeteers display their puppets. Since these walking people are behind the wall on the walkway, their bodies do not cast shadows on the wall faced by the prisoners, but the objects they carry do. The prisoners cannot see any of this behind them, being only able to view the shadows cast upon the wall in front of them. There are also echoes off the shadowed wall of sounds the people walking on the road sometimes make, which the prisoners falsely believe are caused by the shadows. Socrates suggests that, for the prisoners, the shadows of artifacts would constitute reality. (515c) They would not realize that what they see are shadows of the artifacts, which are themselves inspired by real humans and animals outside of the cave. Furthermore, the prisoners would 'assign credit and prestige' to whomever among them could quickly remember which shadows came before, predict which shadows would follow and name which shadows were normally found together. (516c-d)

Leaving the Cave

Allegory of the Cave. Left (From top to bottom): Sun; Natural things; Shadows of natural things; Fire; Artificial objects; Shadows of artificial objects; Analogy level. Right (From top to bottom): "Good" idea, Ideas, Mathematical objects, Light, Creatures and Objects, Image, Metaphor of the sun, and the Analogy of the divided line Socrates then supposes that one prisoner is freed. Suddenly and in pain he is then compelled to stand, turn, walk and look towards the fire. (515c) He is told that what he has formerly seen has no substance and that what he now sees (the carried objects) constitutes a greater reality. He is also asked to identify some of the carried objects. He is unable due to his confusion and he still believes the shadows to be more real. (515d) The freed one is then compelled to look directly at the fire, which hurts his eyes. In his pain, Socrates continues, the freed one would turn away and run back to what he can make out, which now are the carried objects to which he was just previously introduced. (515e) The freed one is then dragged in pain and irritation up and out of the cave. When he reaches the sunlight, he is unable to see anything, his eyes being overwhelmed. (516a) Slowly, his eyes acclimate to the light of the sun. He is first able to see only shadows of things. Next he can see the reflections of things in water and later is able to see things themselves. He is then be able to look at the stars and moon by night and finally he is able to look upon the Sun. (516b) Eventually, he deduces that the Sun is the "source of the seasons and the years, and is the steward of all things in the visible place, and is in a certain way the cause of all those things he and his companions had been seeing" (516bc). (See also Plato's metaphor of the Sun, which occurs near the end of The Republic, Book VI.)[3]

Return to the Cave

Socrates next asks Glaucon to consider the condition of this man. "Wouldn't he remember his first home, what passed for wisdom there, and his fellow prisoners, and consider himself happy and them pitiable? And wouldn't he disdain whatever honors, praises, and prizes were awarded there to the ones who guessed best which shadows followed which? Moreover, were he to return there, wouldn't he be rather bad at their game, no longer being accustomed to the darkness? Wouldn't it be said of him that he went up and came back with his eyes corrupted, and that it's not even worth trying to go up? And if they were somehow able to get their hands on and kill the man who attempts to release and lead them up, wouldn't they kill him?" (517a) The prisoners, ignorant of the world behind them would see the freed man with his corrupted eyes and be afraid of anything but what they already know. Philosophers analyzing the allegory argue that the prisoners would ironically find the freed man stupid due to the current state of his eyes and temporarily not being able to see the shadows which are the world to the prisoners.

Remarks on the Allegory

Socrates remarks that this allegory can be taken with what was said before, namely the metaphor of the Sun, and the divided line. In particular, he likens "the region revealed through sight"the ordinary objects we see around us"to the prison home, and the light of the fire in it to the power of the Sun. And in applying the going up and the seeing of what's above to the soul's journey to the intelligible place, you not mistake my expectation, since you desire to hear it. A god doubtless knows if it happens to be true. At all events, this is the way the phenomena look to me: in the region of the knowable the last thing to be seen, and that with considerable effort, is the idea of good; but once seen, it must be concluded that this is indeed the cause for all things of all that is right and beautifulin the visible realm it gives birth to light and its sovereign; in the intelligible realm, itself sovereign, it provided truth and intelligence and that the man who is going to act prudently in private or in public must see you it" (517bc). After "returning from divine contemplations to human evils", a man "is graceless and looks quite ridiculous whenwith his sight still dim and before he has gotten sufficiently accustomed to the surrounding darknesshe is compelled in courtrooms or elsewhere to contend about the shadows of justice or the representations of which they are the shadows, and to dispute about the way these things are understood by men who have never seen justice itself?" (517de)

Influence

Evolutionary biologist Jeremy Griffith's best-selling book A Species In Denial includes the chapter Deciphering Platos Cave Allegory.[4]

See also

Metaphor of the sun

Analogy of the divided line Form Intelligibility (philosophy) The Form of the Good Nous Plato's Republic in popular culture The Pilgrims of the Sun (1815) (poetry) James Hogg

References

1. ^ Watt, Stephen (1997), "Introduction: The Theory of Forms (Books 57)", Plato: Republic, London: Wordsworth Editions, pp. pages xivxvi, ISBN 1-85326-483-0 2. ^ Elliott, R. K. (1967). "Socrates and Plato's Cave". Kant-Studien 58 (2): 138. 3. ^ Plato, & Jowett, B. (1941). Plato's The Republic. New York: The Modern Library. OCLC 964319. 4. ^ Griffith, Jeremy (2003). A Species In Denial. Sydney: WTM Publishing & Communications. p. 83. ISBN 1-74129-000-7.

External links

Wikisource has original text related to this article: The Republic/Book VII Wikimedia Commons has media related to Allegory of the cave.

Allegory of the Cave at PhilPapers Animated video of Plato's Cave Animated interpretation of Plato's Allegory of the Cave Plato: The Republic at Project Gutenberg Plato: The Allegory of the Cave, from The Republic at University of Washington Faculty Plato: Book VII of The Republic, Allegory of the Cave at Shippensburg University

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Allegory_of_the_Cave&oldid=579167716" Categories:

Platonism Allegory Philosophy of education

Source Material: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Allegory_of_the_Cave YouTube Videos: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d2afuTvUzBQ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-EPz5z1pUag

You might also like

- Sacred GeometryDocument6 pagesSacred GeometryGnosticLucifer75% (12)

- Thelemic MysticismDocument13 pagesThelemic MysticismGnosticLucifer100% (1)

- Platos Cave Allegory - An Exploration of Its Contemporary RelevanceDocument18 pagesPlatos Cave Allegory - An Exploration of Its Contemporary RelevancewhitestarlionNo ratings yet

- MagickDocument15 pagesMagickGnosticLuciferNo ratings yet

- Root RacesDocument10 pagesRoot RacesGnosticLucifer100% (3)

- Black SunDocument11 pagesBlack SunGnosticLucifer86% (7)

- MuDocument8 pagesMuGnosticLuciferNo ratings yet

- Aleister CrowleyDocument41 pagesAleister CrowleyGnosticLucifer100% (2)

- The Allegory of The CaveDocument4 pagesThe Allegory of The CavekristelannNo ratings yet

- AriosophyDocument19 pagesAriosophyGnosticLucifer50% (2)

- Plato's Allegory of the Cave ExplainedDocument48 pagesPlato's Allegory of the Cave ExplainedJeary RoxaNo ratings yet

- Format of The Letter Writing PDFDocument4 pagesFormat of The Letter Writing PDFssathishkumar88No ratings yet

- Nazism and OccultismDocument16 pagesNazism and OccultismGnosticLuciferNo ratings yet

- Plato - Meaning of The Allegory of The CaveDocument4 pagesPlato - Meaning of The Allegory of The CaveelsonNo ratings yet

- AtlantisDocument21 pagesAtlantisGnosticLuciferNo ratings yet

- Holy Guardian AngelDocument8 pagesHoly Guardian AngelGnosticLucifer0% (1)

- Esoteric NazismDocument18 pagesEsoteric NazismGnosticLucifer100% (2)

- Great Work (In Hermeticism & in Thelema)Document5 pagesGreat Work (In Hermeticism & in Thelema)GnosticLuciferNo ratings yet

- Book of RevelationDocument31 pagesBook of RevelationGnosticLuciferNo ratings yet

- 93 (In Thelema)Document6 pages93 (In Thelema)GnosticLuciferNo ratings yet

- Year 11 Physics HY 2011Document20 pagesYear 11 Physics HY 2011Larry MaiNo ratings yet

- LemuriaDocument7 pagesLemuriaGnosticLucifer100% (1)

- 1916 Tavenner Studies in MagicDocument168 pages1916 Tavenner Studies in Magicgtnlmnc99235No ratings yet

- True WillDocument6 pagesTrue WillGnosticLuciferNo ratings yet

- The Secret DoctrineDocument7 pagesThe Secret DoctrineGnosticLuciferNo ratings yet

- Thule SocietyDocument6 pagesThule SocietyGnosticLuciferNo ratings yet

- Meno's Paradox of Inquiry and Socrates' Theory of RecollectionDocument10 pagesMeno's Paradox of Inquiry and Socrates' Theory of RecollectionPhilip DarbyNo ratings yet

- OrphismDocument9 pagesOrphismGnosticLuciferNo ratings yet

- AhnenerbeDocument22 pagesAhnenerbeGnosticLucifer100% (1)

- Isis UnveiledDocument4 pagesIsis UnveiledGnosticLucifer100% (1)

- Notes in Interpreting Plato's DialoguesDocument27 pagesNotes in Interpreting Plato's DialoguesElevic PernisNo ratings yet

- On The Traces of AlcestisDocument30 pagesOn The Traces of AlcestisPino BlasoneNo ratings yet

- Theosophical SocietyDocument9 pagesTheosophical SocietyGnosticLuciferNo ratings yet

- Treviranus ThesisDocument292 pagesTreviranus ThesisClaudio BritoNo ratings yet

- Prophecy of Seventy WeeksDocument13 pagesProphecy of Seventy WeeksGnosticLuciferNo ratings yet

- Sample PPP Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesSample PPP Lesson Planapi-550555211No ratings yet

- Enigma - MeaningsDocument6 pagesEnigma - Meaningssun1986No ratings yet

- Chaos (Cosmogony)Document11 pagesChaos (Cosmogony)GnosticLuciferNo ratings yet

- Hermes Trismegistus' Influence on Early Gnostic ConceptsDocument20 pagesHermes Trismegistus' Influence on Early Gnostic ConceptsMagnus FactorNo ratings yet

- The Golden Verses of PythagorasDocument6 pagesThe Golden Verses of PythagorasGnosticLuciferNo ratings yet

- Novel Intrinsic ElementsDocument12 pagesNovel Intrinsic Elementsfebrian hidayat100% (1)

- Iliad Vs AeneadDocument5 pagesIliad Vs AeneadShirin AfrozNo ratings yet

- The Literary Market: Authorship and Modernity in the Old RegimeFrom EverandThe Literary Market: Authorship and Modernity in the Old RegimeNo ratings yet

- Romulus and Remus Were Twin BrothersDocument5 pagesRomulus and Remus Were Twin BrothersJesen DhillonNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument6 pagesLiterature Reviewapi-256330192No ratings yet

- Plato: Allegory of The Cave: Except From The RepublicDocument36 pagesPlato: Allegory of The Cave: Except From The RepublicAbdullah SaeedNo ratings yet

- Plato - Metaphysics and EpistemologyDocument5 pagesPlato - Metaphysics and Epistemologyaexb123100% (1)

- Plato's Republic Book VI - The FormsDocument1 pagePlato's Republic Book VI - The FormsBettina Borg CardonaNo ratings yet

- We Are All ScientistDocument2 pagesWe Are All ScientistSonim Rai100% (2)

- The Fairie QueeneDocument4 pagesThe Fairie QueenerollercoasteroflifeNo ratings yet

- 53: Matter: Probl Lns DicDocument9 pages53: Matter: Probl Lns Dicjprgg24No ratings yet

- Edmund Spenser Faerie QueenDocument6 pagesEdmund Spenser Faerie QueensumiNo ratings yet

- Style of Bertrand Russell: BiographyDocument9 pagesStyle of Bertrand Russell: BiographyAyeshaKhanKhattakNo ratings yet

- The Art of War, by Sun Tzu 1Document96 pagesThe Art of War, by Sun Tzu 1tbux22No ratings yet

- Plato's Theory of Mimesis and Aristotle's DefenceDocument1 pagePlato's Theory of Mimesis and Aristotle's DefenceNoor KhanNo ratings yet

- The Allegory of The CaveDocument10 pagesThe Allegory of The CaveTracie BirchNo ratings yet

- AristotleDocument19 pagesAristotleGarland HaneyNo ratings yet

- Hamlet Is Not Mad and Does Not Have An Oedipus ComplexDocument3 pagesHamlet Is Not Mad and Does Not Have An Oedipus ComplexJOHN HUDSON100% (2)

- The Depcition of The Devil in Westren Visual CultureDocument54 pagesThe Depcition of The Devil in Westren Visual CultureAdriaan De La ReyNo ratings yet

- Catiline's ConspiracyDocument9 pagesCatiline's ConspiracyekdorkianNo ratings yet

- The Critical ViewsDocument47 pagesThe Critical Viewsmaqsood hasniNo ratings yet

- Yeats Poem Explores Love and DreamsDocument3 pagesYeats Poem Explores Love and DreamsdukespecialNo ratings yet

- Allegory of The Cave - WikipediaDocument45 pagesAllegory of The Cave - WikipediaJoseph Daniel MoungangNo ratings yet

- Allegory of The Cave - WikipediaDocument47 pagesAllegory of The Cave - Wikipediaskand100% (1)

- The Allegory of The CaveDocument5 pagesThe Allegory of The CaveAli HarrietaNo ratings yet

- Wikipedia - Plato Allegory of The Cave - 2017Document6 pagesWikipedia - Plato Allegory of The Cave - 2017iansilva78No ratings yet

- Allegory of The CaveDocument2 pagesAllegory of The CaveCarlos TuazonNo ratings yet

- Plato's Philosophy of RealityDocument2 pagesPlato's Philosophy of RealityMian Umair NaqshNo ratings yet

- The Cave ExplainedDocument2 pagesThe Cave Explainedapi-258902544No ratings yet

- Document 4Document4 pagesDocument 4tanvir.iu.iceNo ratings yet

- Plato AnswersDocument15 pagesPlato AnswersRudrani DattaNo ratings yet

- Plato For Foundations of Philosophical Ethics Class 2Document6 pagesPlato For Foundations of Philosophical Ethics Class 2api-658655088No ratings yet

- Allegory of CaveDocument18 pagesAllegory of CaveShaira DelmonteNo ratings yet

- Theory of Forms Continued: The Divided Line (509d-511)Document4 pagesTheory of Forms Continued: The Divided Line (509d-511)Steffi KawNo ratings yet

- RepublicDocument10 pagesRepublicghada kamalNo ratings yet

- Thesis Allegory of The CaveDocument8 pagesThesis Allegory of The Caveauroratuckernewyork100% (2)

- Untitled DocumentDocument2 pagesUntitled DocumentAynura AbbasovaNo ratings yet

- Description of The Cave: PlatoDocument16 pagesDescription of The Cave: PlatoMark DanielNo ratings yet

- Allegory of The CaveDocument7 pagesAllegory of The CavebrayNo ratings yet

- Plato's Cave Analogy ExplainedDocument8 pagesPlato's Cave Analogy ExplainedNosaj Ozidlareg100% (2)

- The Allegory of the Cave ExplainedDocument5 pagesThe Allegory of the Cave ExplainedMarianne NolascoNo ratings yet

- Plato's "Allegory of The Cave" Explained, Allegorically, Via John Carpenter's "They Live"Document5 pagesPlato's "Allegory of The Cave" Explained, Allegorically, Via John Carpenter's "They Live"OliveNo ratings yet

- Emergence of The Social Sciences: Part 1Document17 pagesEmergence of The Social Sciences: Part 1kristofferNo ratings yet

- Thesis For Allegory of The CaveDocument8 pagesThesis For Allegory of The Cavefjbnd9fq100% (2)

- Plato's Allegory of The CaveDocument2 pagesPlato's Allegory of The CaveAubdool IntiazNo ratings yet

- Diagram Representing The Allegory of The CaveDocument1 pageDiagram Representing The Allegory of The CaveAnonymous VTyRp43jNo ratings yet

- Plato LiteratureDocument34 pagesPlato LiteratureIan BlankNo ratings yet

- PythagorasDocument32 pagesPythagorasGnosticLucifer0% (1)

- Socratic ParadoxDocument4 pagesSocratic ParadoxGnosticLuciferNo ratings yet

- ApocalypticismDocument16 pagesApocalypticismGnosticLuciferNo ratings yet

- Intracardiac Echo DR SrikanthDocument107 pagesIntracardiac Echo DR SrikanthNakka SrikanthNo ratings yet

- Friday August 6, 2010 LeaderDocument40 pagesFriday August 6, 2010 LeaderSurrey/North Delta LeaderNo ratings yet

- Bhikkhuni Patimokkha Fourth Edition - Pali and English - UTBSI Ordination Bodhgaya Nov 2022 (E-Book Version)Document154 pagesBhikkhuni Patimokkha Fourth Edition - Pali and English - UTBSI Ordination Bodhgaya Nov 2022 (E-Book Version)Ven. Tathālokā TherīNo ratings yet

- Ivan PavlovDocument55 pagesIvan PavlovMuhamad Faiz NorasiNo ratings yet

- AR Financial StatementsDocument281 pagesAR Financial StatementsISHA AGGARWALNo ratings yet

- Brochure - Coming To Work in The Netherlands (2022)Document16 pagesBrochure - Coming To Work in The Netherlands (2022)Tshifhiwa MathivhaNo ratings yet

- Lab 5: Conditional probability and contingency tablesDocument6 pagesLab 5: Conditional probability and contingency tablesmlunguNo ratings yet

- Napolcom. ApplicationDocument1 pageNapolcom. ApplicationCecilio Ace Adonis C.No ratings yet

- Merah Putih Restaurant MenuDocument5 pagesMerah Putih Restaurant MenuGirie d'PrayogaNo ratings yet

- Daft Presentation 6 EnvironmentDocument18 pagesDaft Presentation 6 EnvironmentJuan Manuel OvalleNo ratings yet

- Plo Slide Chapter 16 Organizational Change and DevelopmentDocument22 pagesPlo Slide Chapter 16 Organizational Change and DevelopmentkrystelNo ratings yet

- UNIT 1 Sociology - Lisening 2 Book Review of Blink by Malcolm GladwellDocument9 pagesUNIT 1 Sociology - Lisening 2 Book Review of Blink by Malcolm GladwellNgọc ÁnhNo ratings yet

- Towards Emotion Independent Languageidentification System: by Priyam Jain, Krishna Gurugubelli, Anil Kumar VuppalaDocument6 pagesTowards Emotion Independent Languageidentification System: by Priyam Jain, Krishna Gurugubelli, Anil Kumar VuppalaSamay PatelNo ratings yet

- Vol 013Document470 pagesVol 013Ajay YadavNo ratings yet

- 12 Smart Micro-Habits To Increase Your Daily Productivity by Jari Roomer Better Advice Oct, 2021 MediumDocument9 pages12 Smart Micro-Habits To Increase Your Daily Productivity by Jari Roomer Better Advice Oct, 2021 MediumRaja KhanNo ratings yet

- Derivatives 17 Session1to4Document209 pagesDerivatives 17 Session1to4anon_297958811No ratings yet

- Second Year Memo DownloadDocument2 pagesSecond Year Memo DownloadMudiraj gari AbbaiNo ratings yet

- Criteria For RESEARCHDocument8 pagesCriteria For RESEARCHRalph Anthony ApostolNo ratings yet

- Other Project Content-1 To 8Document8 pagesOther Project Content-1 To 8Amit PasiNo ratings yet

- City Government of San Juan: Business Permits and License OfficeDocument3 pagesCity Government of San Juan: Business Permits and License Officeaihr.campNo ratings yet

- Dyson Case StudyDocument4 pagesDyson Case Studyolga100% (3)

- Ettercap PDFDocument13 pagesEttercap PDFwyxchari3No ratings yet

- Grinding and Other Abrasive ProcessesDocument8 pagesGrinding and Other Abrasive ProcessesQazi Muhammed FayyazNo ratings yet

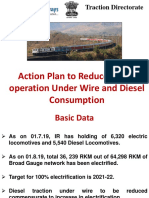

- Final DSL Under Wire - FinalDocument44 pagesFinal DSL Under Wire - Finalelect trsNo ratings yet

- Term2 WS7 Revision2 PDFDocument5 pagesTerm2 WS7 Revision2 PDFrekhaNo ratings yet

- M Information Systems 6Th Edition Full ChapterDocument41 pagesM Information Systems 6Th Edition Full Chapterkathy.morrow289100% (24)

- MEE2041 Vehicle Body EngineeringDocument2 pagesMEE2041 Vehicle Body Engineeringdude_udit321771No ratings yet