Professional Documents

Culture Documents

W.J. Rorabaugh The Alcoholic Republic An American Tradition 199

Uploaded by

Walter WattsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

W.J. Rorabaugh The Alcoholic Republic An American Tradition 199

Uploaded by

Walter WattsCopyright:

Available Formats

THE

ALCOHOLIC

REPUBLIC

AN AMERICAN TRADITION

w. J. RORAAUGH

W W

New York Oxford

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

1979

THE GROG-SHOP

o come le t us all to the grog-sho:

The tempest is gatheri ngfast-

The re sure l is nought like the gog-shop

To shield from the turbulet blat.

For there will be wrangli ng Will

Diputi ng about a lame ox;

And there will be bullyi ng Billy

Challengi ng negroes to box:

Tob Filpot with carbuncle nose

Mii ng politics up with his liquor;

Tim Tuneul that sings even prose,

And hiccups and coughs in his beaker.

Dick Drows with emeral ees,

Kit Crusty with hair like a comet,

Sam Smootl that whilom gew wise

But retured like a dog to his vomit

And there will be tipli ng and talk

And fudli ng and fun to the lie,

And swagering, swearng, and smoke,

And shufi ng and scufing and strie.

And there will be sappi ng o horses,

And betti ng, and beati ng, and blows,

And laughter, and lewdness, and loses,

And winning, an woundi ng and woes.

o then let us oto the grog-shop;

Come, father, come, jonathan, come;

Far drearier far than a Sunda

Is a storm in the dulness o home .

GREEN'S

ANTI-INTEMPERANCE

ALMANACK (1831)

PREFACE

Tm PROJECT began when l discovered a sizeablecollec-

tion of early nineteenth-century temperance pamphlets .

As lreadmosetracts , lwonderedwhathadprompted so

many authors to expend so much effort and expense to

attack alcohol. l began to suspect that the temperance

movement had been launched in the i 8zos as a response

to a period of exceptionally hearty drinking. The truth

was startling. Americans between i ;o and i 8o drank

more alcoholic beverages per capita than ever before or

since. !ittlehasbeenwrittenaboutthisveritablenational

binge, and some reectionconcening the development

ofAmerican historiography explains theneglect.

lnthenrstplace,throughoutmostofAmericanhistory

alcohol has been a taboo subject. While nineteenth-cen-

tury librarians nled references to it under a pejorative,

the 'liquorproblem, ' properpeopledidnotevenmention

strong beverages . either did historians, who long ne-

glected the fact that the United States had been one of

theworld'sgreatdrinkingcountries. Arecentbiographer

ofPatrick Henry, Ceorge Willison, tells us that one of

Henry's early biographers transformed that patriot's

taven-keeping for his father-in-aw into occasional visits

to that drinking house. And a few years later Henry's

grandson wrote a biography that did not even mention

the taven. Sometimes, late nineteenth-century authors

7

Preace

became politely vague. When Richard H. Collins in his

Histor of Kentucky (!ouisville, i 8;;), ;6;, described

Thomas F. Marshall , adrunkardnephewofChief|ustice

|ohn Marshall , he wrote, 'ln spite of his great

weakness~a weakness which often made him disagree-

able and unwelcome to his best friends, the weakness

most common among men of brilliant promisehe was

intrutharemarkableman. . . . "Thuswastheinnuendo

closed with a dash, as the authorretreated behind a fa-

cadeofrespectability.

ln the second place, American historians traditionally

have focused upon political events, especially upon such

obvious turning points as the Revolution and the Civil

War, withthe consequence thatlifeduringtheyears be-

tween those wars has often been ignored. Even scholars

who have written on the early nineteenth century have

emphasized politics , including Arthur M. Schlesinger,

|r. , in his path-breaking The Age o Jackson. That work,

published in i , led a generation ofhistorians to see

|acksonian America primarily as the era thatgave birth

to moden liberal values . This viewgavethe period afa-

vorable reputation until it was discovered that Andrew

|ackson, that primordial liberal , had been a holder of

slavesanda slayeroflndians .

During the i6os, while scholars were recoiling from

|acksonandlosing interest in his times , Americans were

living through unprecedented turmoil. We discovered

that social change had the potential to be as tumultuous

and alarming as political change. Historians began toex-

amine more closely thesociaI changes that had occurred

in the United States in past times, and they began to

question theutility ofsuch turningpoints asthe Revolu-

tionortheCivil War. A number ofstudies ofewEng-

land towns during the colonial period pointed to the

importance of evolutionary change as the basis for

lon

[

-termrearrangementsofthe socialorder. The impact

7

Preace

of industrialization during the mid-nineteenth century

began to attract more attention, and that interest stimu-

lated a number ofworks focusing on such developments

as the American railroad. A rising consciousness about

ethnicityled to studies ofimmigrant groups . Thechang-

ing roles of women were investigated. Most of these

inquiries, either explicitly or implicitly, eroded the im-

portance of such customary dividing points as the

Revolution or the Civil War, and, indeed, the prolifer-

ation of social history threatened to leave much of the

American past without signincant turningpoints.

The present study sugests a new turning point. The

changes indrinkingpattens that occurred between i ;o

and i 8o were more dramatic than any that occurred at

anyothertimeinAmericanhistory. Furthermore, theas-

sociation of particular pattens in the consumption of

alcoholwith certain socialandpsychological traits has led

metoconcludethattheUnited Statesinthoseyears un-

derwent such profound social and psychological change

that a new national character emerged. lndeed, the

American of i 8o was inassumptions, attitudes , beliHs,

behavior, andmind closertotheAmerican of i 6o than

to his own grandfather. ln other words, the early nine-

teenth century was a key formative period in American

social history.

Thisprojectbeganwithmoremodestaims . Aslbegan

toinvestigate the period ofhighconsumptionduringthe

earlynineteenth century, l considered who drank, what

theyimbibed,whenandwheretheyconsumed. Hadthis

work never advanced beyond those questions , it would

havebeenasuggestivethoughinchoateessay in manners .

What has enabled me to consider broader questions has

beentheuseofthetheoreticalliteratureon theconsump-

tion of alcohol . From the work of social scientists who

examined the drinking mores in particlar cultures and

made cross-cultural comparisons ofdrinking in primitive

7

Preace

societies , llearned thatdrinkingcustoms and habits were

not random but reective of a society's fabric, tensions,

and inner dynamics , and ofthepsychological sets ofits

people. Becausethewealthofthis material enabledmeto

apply social science theory to many of my observations

ofdrinkingpattensinnineteenth-centuryAmerica, lwas

able, consequently, to draw conclusions concerning the

psychology and social behavior of Americans in that

period. At the same time, this inquiry became a kind of

laboratoryin whichtotest hypothesesfromthe literature

onalcohol . lnthatsense, theorists ofdrinkingmotivation

can viewthework as a historical case study.

And here l will add a waning. Because this book

mixeshistoryandthesocialsciences, itemploysmethods

that are not traditional to any single discipline, and its

conclusions are sometimes more suggestive than

rigorously proved. My justincation for such speculation

is that there is a need for books that provide questions

ratherthan answers . ltmatters less that my speculations

are correct, although l hope that some of them will be

proved in time, than that l have provoked the reader to

think and explore for himself. That is why l wrote the

book.

Finally, bywayofappreciation, l wouldliketooffersev-

eraltoasts. First, tothemany cooperativelibrarians, par-

ticularlythoseatthe Congregational Society !ibrary and

Harvard's Baker Business !ibrary Manuscripts Depart-

ment; to helping friends , Suzanne Aldridge, Steve Fish,

BillCienapp,KeithHoward,TonyMartin, Steveovak,

Roy Weatherup, Hugh West, and Kent Wood; and to

friendly critics , |oe Corn, Harry !evine, Charles Roy-

ster, |oseph Ryshpan, and Wells Wadleigh. l also raise

my glassto DavidFischerfor suggesting alogical format

for presenting consumption statisti cs ; to Bruce Boling

7

Preace

and

Kirby Miller for access U many lrish immigrantlet-

ters; toEdward Pessen forcomments on my dissertation;

and U Michael McCiffert and Cary Walton for critiqu-

ingearlydraftsofchapterstwoandthree,respectively. An

earlier version ofmy consumption estimates appeared in

Estimated U.S. Alcoholic Beverage Consumption,

1790-1 860, " Journal o Studies on Alcohol, 37 (1976) ,

357-364. Thenext roundhonorsAlfredKnopf, lnc. ;th

Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore; and the Rhode-

lsland Historical Society, respectively, for permission to

reproduce three illustrations. Photographs were made at

the University of California, Berkeley, and the Univer-

sity ofWashington. Permission was given to quotefrom

several manuscript collections. Benj amin Rush Papers ,

Historical Society of Pennsylvania; Michael Collins Pa-

pers, Duke University; Robison Family Papers , Maine

Historical Society; |. H. Cocke Papers, Mrs . Forney

|ohnstonandtheUniversityofVirginia; and BaconFam-

ily Papers, YaleUniversity.

l also salute the members of my thesis committee at

Berkeley, Troy Duster, Winthrop|ordan, andespeciaIly

chairmanCharles Sellers. Heshepherdedthisworkfrom

its inception to its completion as a thesis, waned me of

numerous pitfalls , and made many helpful suggestions,

including the title. The University ofCalifornia, Berke-

ley,gavennancial supportasaTeachingAssistantand as

a Dean's Fellow with a travel allowance. l owe a special

toast to Elizabeth Rosenneld. Her generosity in provid-

ing a place to write and inimitable dinner conversation

sped my thesis toits conclusion. Minewas the sixthdis-

sertationwritteninherhome.Morerecently, shehasex-

ercised her editorial skill upon the manuscript. We did

notalwaysagree. herwhiskieis Scotch;mine,as anative

of Kentucky, is not. My nnal salutes are to Richard R.

|ohnson, Otis Pease, andmyothercolleaguesatthe Uni-

versity of Washington; to Ann Pettingill , whose assis-

7

Preace

tance was madepossible by a grant from the University

of Washington Alcoholism and DrugAbuse lnstitute; to

SheldonMeyer,whogaveearlyencouragement;to Susan

Rabiner, Phyllis Deutsch, and everyone at Oxford; and

to my sister, Mary Rorabaugh, who helped solve a last

minute crisis.

W. |. R.

Seattle

June

13, 1979

7

CONTENTS

Chapter

A NATION OF DRUNKARDS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3

2 A GOOD CREATURE .... .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

3

3

TH SPIRITS OF INDEPENDENCE . . . . . . . . . . .

59

4 WHSKEY FEED . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93

5

TH ANXIETIES OF THIR CONDITION. . . . . . 12

3

6 TH PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . i47

7 DEMON RUM .. . .. ...... . .. . .. .. .. . . . ... 1

8

5

Append

1 ESTIMATING CONSUMPTION OF ALOHOL . . . . 22

3

2 CROSs-NATIONAL COMPARISONS OF

CONSUMPTION. .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

3

7

3

COOK BOOKS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 240

4 REVIEW OF DRINKING MOTIVATION

LITERATURE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . + .. . .. . . 241

7

Contents

5 QUANTITATIVE MEASUREMENTS e .. e e . e e e 247

6 A RECIPE e . e e e e ... e e . e e e . e e . e e e e e 250

Bibliographical Note . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. 251

Ke to Abbrevitions ........................ 254

ht kL|0h0L| KtlL|

Notes e o e e e o e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e 256

Index .................................... 295

7

PLENTY

A geogrphy lesson.

r

7

2

'

P

c

!

c

7

! (

P

2

a t.

!

ea

M

<

O

=

2

t

c '

=

!

C

:.

<

t ..

c *

>

f

=

c

-

c D

=

~ c

e >

=

C

=

... V

g

P

=

!

' P (

O

P

g

c

C

(

P

2

C

> s

.

... a

t

=

P

0

a

7

C

0

=

P

P

~

W

=

o

t

=

t

W

\AS EARLY nineteenth-century America really a nation

ofdrunkards?Certainlytheclergymenwhowerecrusad-

ingfortemperancethoughtso, asexcerptsfromtheirser-

mons and addresses attest. These self-appointed moral

guardians, convinced that a hearty indulgence in alcohol

was commonplace, increasing, and unprecedented, were

nlled with apprehension, their sermons nlled with de-

spair. lntemperance, they warned, waswidespread, too

obviousnottobenoticed;'socommon, asscarcelytobe

thought criminal;' the fashionable vice of the 'day. '

They noted, too, that the United States was among the

most addicted ofnations, that in this respect it had out-

stripped all Europe, and that no other people ever in-

dulged, souniversally. 'Evenmore alarmingintheireyes

wasthe factthatthis intemperancewasspreadingwider

and wider;'liketheplague;' throughoutourcountry;'

withthe rapidityandpowerofatempest. 'otonlydid

theyseeexcessiveuseasthe cryingsinofthe nation, but

they believed it to be agrowing evil ;' ''til increasing; "

until America was fast becoming a nation of drunk-

ards . '

A similaralarmwasvoiced bythe nation's mostprom-

inent statesmen. lt was not so much the use of alcohol

tbat worried themthey all drankto someextent~as its

excessive use. Ceorge Washington, a whiskey distiller

5

: ~,=.: m mmmmm

The Alcoholi c Republic

himself, thought that distilled spirits were the ruin of

half the workmen in this Country. . . . ' |ohn Adams,

whose daily breakfast included a tankard ofhard cider,

asked, . . . is it not mortifying . . . that we, Ameri-

cans, should exceed allother . . . peoplein the world in

this degrading, beastly vice of intemperance:' And

Thomas |efferson, inventor of the presidential cocktail

party, feared that the use of cheap, raw whiskey was

spreading through the mass of our citizens . ' ln I 82 I

Ceorge Ticknor, a wealthy Boston scholar, warned |ef-

ferson, lfthe consumption of spirituous liquors should

increase for thirty years to come at the rate it has for

thirty years back we should be hardly better than a na-

tion of sots. ' The Founding Fathers, fearful that the

Americanrepublicwould be destroyed ina ood ofalco-

hol, were anguished and perplexed.

Otherobservers, more dispassionate butno less articu-

late, found Americandrinking habits deplorable. Foreign

travellers, forinstance, were surprisedand shocked atthe

amount of alcohol they saw consumed. A Swedish visi-

tor, Carl D. Arfwedson, reported a general addictionto

hard drinking, ' while a visitor from England, lsaac

Holmes, noted that intoxication pervaded all social

classes. lt was not surprising that Basil Hall, a retired

Royal avy Captain hosnle to the new nation's demo-

craticideals, should beperfectlyastonishedattheextent

ofintemperance. 'But even the sympathetic English re-

former, WilliamCobbett, deplored American tippling. l

almost wished, ' he wrote, that there were Borough-

mongers here totax these drinkers. '

The more discerning visitors observed that while

heavy drinking was widespread, public drunkenness was

not common. This fact led William Dalton to suggest

that Americans betterdeservedthe appellation oftipplers

thanofdrunkards . lnfrequency ofconspicuous drunken-

ness, however, was not inconsistent with an extensive

6

A NATON OF DRUNKARDS

overuse of alcohol . As a shrewd Scot by the name of

Peter eilson pointed out, thenation's citizenswerein

a certain degreeseaoned, andconsequentlyit[was]by no

means common to see an American very much intoxica-

ted. ' lnotherwords, as a resultofhabitualheavy drink-

ing Americans had developed a high degree oftolerance

for alcohol . Even so, in the opinion of lsaac Candler,

Americanswerecertainlynotsosoberasthe Frenchor

Cermans, but perhaps, ' he guessed, about on a level

withthe lrish. '

American travellers expressed similar views . They

found a great want ofeconomy in the use ofspirituous

liquors , 'notedthatdrunkenness waseverywherepreva-

lent, 'and pronounced the quantity ofalcohol consumed

to bescandalous . 'Thewell-travelledAnneRoyall, who

spent much ofher life crisscrossing the country in stage

coaches, wrote, When l was in Virginia, it was too

muchwhiskeyin Ohio, too muchwhiskeyin Tennes-

see, it is too, too muchwhiskey| '

lt was the consensus, then, among a wide variety of

observers that Americans drank great quantities ofalco-

hol. The beverages they drank were for the most part

distilled liquors, commonly known as spiritswhiskey,

rum, gin, andbrandy. Ontheaveragethoseliquorswere

45 percent alcohol, or, in the language of distillers, 90

proof. lt was theunrestrained consumption ofliquorsof

suchpotencythatamazedtravellersandalarmedsomany

Americans. And there was cause for alarm. During the

nrstthirdofthe nineteenthcenturythetypical American

annually drank more distilled liquor than at any other

time inourhistory.

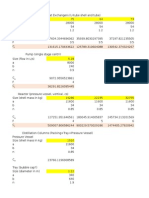

A briefsurveyofAmericanalcoholconsumptionfrom

the colonial period to the present will help us put the

early nineteenthcenturyinproperperspective. As Chart

. shows,duringthecolonial periodtheannualpercap-

ita consumptionofhard liquor, mostly rum, reached 3.7

7

. .. ,.. ,,,,,,,,,,,,

The Alcoholic Republi

6

4

Chart 1.1. ANNUAL CONSUMPTION of DISTILLED

SPIRITS (i.e., Rum, Whiskey, Gin, Brandy)

per CAPITA, in U.S. GALLONS.

gallons . Afterthe Revolution, becauseofdecreased trade

withthe Westlndies, highimportdutiesonWestlndian

rum and on the West lndian molasses from which ew

Englandrumwasmade,andanewtaxondomesticwhis-

key, the consumption of distilled liquors declined by

one-quarter. Butby i 8oo, prosperity, improveddistilling

technology, the growing popularity ofwhiskey together

with illicit and the

efore untaxed distilled spirits had

combined to raise per capita consumption to the i ;;o

level . Then, between i 8oo and i 8o, annual per capita

consumptionincreaseduntilitexceeded gallons~a rate

nearly triple thatoftoday'sconsumption. After i 8othe

temperancemovement, and lateronhighfederaltaxation

discouraged the drinking of distilled beverages . Annual

percapita consumptionfellto less than z gallons, a level

fromwhichthere hasbeenlittledeviationin morethana

century.

8

A N A nON OF DRUNKARDS

4

2

I720 I770 I820 I870 I20 I70

Chart 1.2. ANNUAL CONSUMPTION of ALCOHOL

CONTAINED in ALL ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES

per CAPITA, in U.S. GALLONS.

ln addition to distilled spnts, Americans drank

weaker fermented beverages: beer (% alcohol), hard

cider ( i o%), and wine (i 8%). Colonial beer consumption

was negligible, except for home brewed 'small beer,'

which was only one percent alcohol . Until i 8o annual

per capita consumption of commercial beer at no time

reached z gallons, anditwasnotuntilafterthe CivilWar

thatitrosedramaticallytowardtoday'srateofmore than

i 8 gallons. But hard cider was a different matter. Pre-

Revolutionary cider consumption, heaviest in the apple

country from Virginia northward, was probably as high

if not higher than in the early nineteenth century. ln

fact, so much cider was drunk that colonial Americans

probably ingested more alcohol from that beverage than

from their much more potent rum. And even with the

increased popularity ofdistilled spirits aner i 8oo, thean-

nual per capita consumption of hard cider was i or

9

The Aloholic Reublic

more gallons . lt continued until the 1 830S to accountfor

a signincant proportion ofall the alcohol Americans im-

bibed. Hard cider disappeared only after the leaders of

the temperance movement succeeded in persuading

farmers tocutdowntheirappletrees. Wineconsumption

wasandalwayshasbeenrelativelylight . ln 1 770 thetyp-

ical American annually drank only one-tenth ofa gallon,

between 1 770 and 1 870 less than a thirdofa gallon, and

even today less than one and a halfgallons .

From thequantityofeachbeveragedrunkand theper-

centage of alcohol in each, it is a simple matter, of

course, to compute the total amount of alcohol con-

sumed. AsChart 1. 2 shows,in 1770 theannualpercapita

i

_

take of alcohol from all sources was 3.5 gallons. ln

the years following the Revolution the amount declined

asthe consumptionofspirits declined. But after 1 800, as

the quantity of spirits consumed increased, the total

quantity of alcohol consumed from all sources increased

until it reached a peak ofnearly 4 gallons per capita in

1 830. This rate ofconsumption was the highest in the

annals of the United States. After reaching this peak,

consumptionfell sharplyunderthe inuence ofthe tem-

perancemovement, and since 1 840 itshighestlevelshave

beenunder 2 gallonslessthanhalftherateofconsump-

tion in the I 820S.

6

Drinking in the young nation was obviously hearty,

not to say excessive. However, the charge made by

alarmed clergymen and statesmen that in this respect

Americahadoutstrippedeveryothernationwasexagger-

ated. A comparison of the annual per capita intake of

alcohol in the United States with thatinother countries

during the early nineteenth century shows that Ameri-

cans drank more than the English, lrish, or Prussians,

butaboutthesame asthe Scots or French, andlessthan

the Swedes. The nations with high consumption rates

tendedtosharecertaincharacteristics . ExceptforFrance,

1

........~~-~~.~-+~

L

A NATION OF DRUNKARDS

where wine predominated, the remaining heavy drinking

countries, Scotland, Sweden, and the United States,

weredistilledspirits strongholds. Thesenationswereag-

ricultural , rural, lightly populated, and geographically

isolatedfromforeignmarkets;theyhad undercapitalized,

agrarian, barter economies; they were Protestant . ln all

three cheap, abundantgrainfed the distilleries . By con-

trast, consumption was low in lreland and Prussia be-

cause their economies lacked surplus grain and, hence,

could not support ahighlevelofdistilled spirits produc-

tion. ln England high spirits taxes had encouraged the

populace to switch from whiskey and gin to beer. Al-

thoughearlynineteenth-centuryAmericansdid notdrink

more than reIatively afuent Europeans of that era, by

modern standards they drank a lot. A recent survey of

alcohol consumption in ten European countries shows

only France with a higher per capita consumption than

the American rate during the early nineteenth century

and shows nve countries drinking at less than half that

rate.

SothetypicalAmericanwasdrinkingheartily, butnot

all Americansdranktheirshare. ltis impossibletoobtain

anexactaccounting, buttheAmericanTemperance Soci-

etyestimatedthatduringeachyearofthelate 1 820S nine

million women and childrendrank 12 million gallons of

distilled spirits,threemillionmen, 60 milliongallons . At

this high point the average adult male was imbibing

nearly a halfpinta day. Few, however, were average. lt

was calculated that halfthe men drank 2 ounces a day;

one-quarter (habitual temperate drinkers"), 6 ounces;

one-eighth (regular topers, and occasional drunkards"),

1 2 ounces, and another eighth (connrmed drunkards'),

24 ounces. Thus, halfthe adult males-ne-eighthofthe

total population~were drinking two-thirds ofall thedis-

tilledspiritsconsumed.8

While men were the heartiesttopers, women werenot

I I

The Alcoholic Republic

Men were the heartiest toers.

faint-hearted abstainers . Little, however, can be learned

abouteitherthereputed i oo,ooofemaledrunkards orthe

more numerous women who consumed from one-eighth

toone-quarterofthe nation's spirituous liquor. The sub-

jectreceivedscantattentionbecauseitwas'too delicate'

to be discussed. The ideal offemininity did discourage

tippling, for a woman was supposed to show restraint

consistent with virtue, prudence consonant with deli-

cacy, andapreferenceforbeveragesagreeabletoa fragile

constitution. The public was not tolerant of women

drinking at taverns or groceries, unless they were trav-

ellers recoveringfroma day's arduousj ourney. Then the

ladies might be permitted watered and highly sugared

spirituous cordials ."

The concept of feminine delicacy led women to drink

alcohol-based medicines for their health; many who

regarded spirits as 'vulgar' happily downed a highly al-

12

A NATION OF DRUNKARDS

coholic 'cordial or stomachic elixir. 'Furthermore, there

were some social occasions when it was proper for

women to imbibe freely and openly. For example, east-

ern ladies drank in mixed company at society dinners,

suppers, and evening parties, and at pioneer dances the

'whiskey bottle was . . . passed pretty briskly from

mouth to mouth, exemptingneither age nor sex. 'A sur-

prised Frances Kemble learned that ew York ladies

whovisitedthepublicbathswere'prettyonen' supplied

withmintjuleps . Still, becauseawomanhadtoconform,

at leastoutwardly, to the social precepts ofthe day, she

wasmostlikelytodrinkintheprivacyofherownhome.

There shecould suitherself. Theusualrolesofmaleand

female were reversedwhentemperancereformerEdward

Delavan called upon Dolly Madison. After the teeto-

taling Delavan declined a drink, the ustered hostess de-

clared that 'such an example was worthy of imitation'

and proceeded to mix herselfa toddy.

t

Southern slaves, like women, drank less than their

share ofliquor. Masters usually provided watered spirits

as a work incentive during harvest time, and many al-

lowed their bondsmen a three-day spree at Christmas.

The law, however, generally prohibited blacks from

drinking at other times . This prohibition was only par-

tially effective. Blacks in some districts were reputed to

be amajority oftaverncustomers, and slavesoften found

that they could acquire liquor by bartering their own

garden vegetables or hams purloined from the master.

OneWarrenton,orthCarolinamancomplainedthaton

Sunday afternoon the streets were 'infested with

drunken negroes stagering from side to side. ' Jhis ob-

server concluded that custom was 'stronger than law. '

Denanceoftheliquorlawsledtotougherstatutes. orth

Carolina, for example, in I ;8 prohibited retailers from

sellingalcohol to slaves iftheir owners objected; in I 88

forbade slaves from vending liquor, and in i 8 forbade

The Alcoholic Reublic

themfrombuying spirits under any condition. But these

legal restraints against slaves drinking were less effective

indiscouragingconsumptionthanwastheplantationsys-

tem under which there was neither the opportunity to

obtainliquornorthemoneytobuyit. As Eugene Ceno-

vese has pointed out, the slaves' principal drinking prob-

lem was the drinkingoftheir masters .

White males were taught to drink as children, even as

babies . lhave frequently seenFathers ,'wrote one trav-

eller, wake their Child ofa yearold from a sound sleap

tomake it drink Rum, or Brandy. ' As soon as a toddler

was old enough to drink from a cup, he was coaxed to

consume the sugary residue at the bottom of an adult's

nearlyemptyglassofspirits. Manyparentsintended this

early exposure to alcohol to accustom their offspring to

xhe tasteofliquor, to encourage them to accepttheidea

of drinking small amounts, and thus to protect them

from becoming drunkards . Children grew up imitating

their elders' drinkingcustoms. Boys who played 'militia'

expected the game to end, like their fathers' musters,

with a round of drinks. Adolescents perceived drinking

at a public house to be a mark of manhood. Sometimes

theswaggeringyoungmalemadearidiculouspicture. lt

is nouncommonthing,'wroteone man, to see a boyof

twelve or fourteen years old . . . walk into a tavern in

the forenoon to take a glass ofbrandy and bitters . . . . '

Men encouraged this youthful drinking. Many a proud

fatherglowed when hissonbecameoldenoughto accom-

pany himtothe tavern where they could drink asequals

fromthe same glass.

The male drinkingcultpervaded all social andoccupa-

tional groups . A western husbandman tarried at the tav-

ernuntil drunk, aneastern harvest laborerreceived daily

ahalfpintorpintofrum,a southern planterwasconsid-

ered temperate enough to belong to the Methodist

Church if he restricted his daily intake of alcohol to a

v

.

A NATON OF DRUNKARDS

quart of peach 5randy. A city mechanic went direetly

from work to the public house where he stayed late and

spenthisday'swages. Alcoholwas suchanaccepted part

of American life that in r 8z the secretary of war e-

titnated that three-quarters ofthe nation's laborers drank

daily at least 4 ounces ofdistilled spirits. Liquorwas so

popular that the army dared not bar the recruitment or

reenlistmentofhabimal drunkards . lfsuch a policy were

adopted, warned the surgeon general , the army might

have to be disbanded. The middle classes were scarcely

more sober. Attorneys disputed with physicians as to

which profession was the more besotted. Even more

shocking was the indulgence ofclergymen. One minister

whoconsideredhimselftemperatesystematicallydowned

4 glasses of spirits to help him endure the fatigues of

Sunday. At Andover Seminary, one ofthe most impor-

'5

The Alcoholic Reubli

tant centers of temperance activity, students reguIarIy

drank brandy toddies at the IocaI tavern. Perhaps this

practice wasnecessaryto prepare wouId-be ministersfor

keeping up with theirfuture congregations . '

Drinkingbytheseenthusiastictoperswasdoneinava-

riety of pIaces , incIuding, of course, taverns . AIthough

the originaIpurposeofpubIichouses hadbeentoprovide

traveIIers a pIace to obtain refreshment, most IocaIities

had so few traveIIers that tavern owners found it neces-

saryfortheireconomicsurvivaIto attractIocaIcustomers

to the bar. Even so, the typicaIearIy nineteenth-century

tavern recorded fewer than nny visits a week. HaIf of

thesetripswere madebythesame fouroreightmen,the

reguIars who gathered every day or two around the pot-

beIIied stove to taIk about the crops and weather, to

argue poIitics, to quarreI and nght over insuIts, and, of

course, to drink. They usuaIIytreated, that is, eachman

bought a haIfpint ofwhiskey, which was passed around

theroom. Sinceeverymanwasexpectedtotreatinturn,

byevening'sendeachhad drunkhaIfa pint. Withsofew

reguIars , the soIvency of most pubIic houses depended

upon the Saturday trade, when as many as twenty men

mightgather to drink a haIfpint apiece. lt appears that

the typicaI man patronized a pubIic house once a week,

thatthese visits provided him with i quarts ofdistiIIed

spirits a year, and that this amount represented about

one-nnh of

his annuaI consumption.'

Most Iiquor was drunk in the home, where whiskey

andrumprovidedmeaItimedrinks, customaryrefreshen-

ers, and hospitabIe treats for guests. FashionabIe peopIe

owned ornate Iiquor cases or eIaborate sideboards that

containednumerousbottIes ofvariouscordiaIs , incIuding

miId, sweet, fruit-avored eIixirs fortheIadies. Eventhe

poorest host proffered his whiskey j ug. WhiIe some of

this Iiquor was made on the premises, bartered from

neighbors, orboughtat a distiIIery, much camefromthe

1 6

A NATION OF DRUNKARDS

generaIstore, where its saIe was oftenthe mostimportant

itemofbusiness . AIthough somemerchantscurriedfavor

withtheircustomers bypIyingthemwithfreesampIesof

their spirits, IessIiquorwasgivenawaythan wassoIdfor

home use. A study of one ew Hampshire store's

recordsfrom i 8 i oto i 8 showedthatfarmers whopur-

chased suppIies usuaIIy bought Iiquor aIong with their

other purchases. During the earIy r 8zos one-quarter of

the vaIue ofthis store'stotaI saIes was aIcohoI; typicaIIy,

at that time, in a transaction that was for more than $ r

The Aloholic Republi

and that included the sale of alcohol , distilled beverages

accounted formore than halfthevalueofthe sale. A de-

cade later less than one-tenth of the value oftotal sales

wasliquor, in atransactionover$ 1 thatincluded alcohol,

spirits were butone-third the value ofthe sale.

1

Leavinghome,however, didnotrequirethatanAmer-

ican forego his favorite beverage. When journeying by

stage coach, travellers could obtain liquor at the inns

where thehorses were changed. Duringone arduous se-

venteen-hour, sixty-six mile trip across Virginia, the

stage stopped ten times, and two ofthe passengers had

drinksateachway station: tendrinks apiece. Suchhabits

led one foreign observertoconcludethat'the American

stage coach stops every nve miles to water the horses,

andbrandy the gentlemen! " Withtheinventionofsteam-

boats, Americans were provided with yet another place

to drink. Whereas stage travellers had been able to im-

bibe only when their vehicle rested at a wayside inn,

boatpassengersusuallyfounda barconvenientlysituated

in the gentlemen's compartment, on the middle deck

abovethe engine room. This arrangement is telling. The

locationofthe bar notonly discouraged female travellers

fromdrinking,italsoindicatesthatthebarwasthe boat's

central feature. Of all forms of public transportation,

onlythe steamboatfocused so muchattentiononthe bar.

ln part, this design reected the owners' hopes for high

prontsfromliquorsales,someboatswerelittlemorethan

oating saloons. More important is the fact that the

steamboat was conceived at a time when drinking was

central to American society. Boat designs that stressed

bars conformed to a cultural imperative. '

Americansdranknotonlyanyplace butalsoanytime.

Somebeganto imbibeevenbefore breakfastwithan eye

opener concocted of rum, whiskey, orgin mixed with

bitters . lnone Rhode lslandfactory town, laborers going

to workmadetheirwaythroughthedawn'searly lightto

1 8

A NATION or DRUNARDS

the tavern to take a little drop. ' Centlemen adjourned

frombusiness at 1 1 :00 A.M. for theold-fashioned equiva-

lentofthecoffee break, the'elevens, ' anoccasionfor par-

taking ofspirituous liquor. Whenthe weather was cold,

they

migbt have hot toddies made of whiskey or rum,

sugar, and hot water, or hot slings made

f

.

gin, sugar,

and hot water. At times a little lemon jurce, cherry

brandy, or bitters was added. The Virginia gentry gath-

ered at 1 :00 P.M. , anhour before dinner, for the purpose

of taking juleps compounded of peach brandy or whis-

key, sugar, and ice. Sometimes crushed

int was added

to make a mint julep. Throughout America early after-

noon dinner was accompanied by hard cider or distilled

spirits mixed with water, in late afternoon cam

anoth

r

break, then supper with more refreshment. Fmally, m

the evening it was time to pause and reect upon

he

day's events while sitting by the home or tavern nreside

sipping spirits .

J8

. .

Americans drank on all occasions. Every social event

demanded a drink. When southerners served barbecue,

they roasted hogs and provided 'plenty owhi

.

skcy. '

Cuests at urban dances and balls were often mtoxicated,

so were spectators at frontier horse races. Western ne

-

lyweds werecustomarilypresentedwithabottleof

his-

key to be drunk before bedding down for th

mght.

Liquor also entered into money-making and busmess af-

fairs . When a bargain was negotiated or a contract

signed, it was sealed with a drink, auctioneers passed a

whiskey bottle to those who made bids. After t

.

he h

r-

vest, farmers held agricultural fairs that ended with d

n-

ners laced with dozens of toasts. Whiskey accompamed

traditional communal activities such as house-raisings,

huskings, land clearings , and reaping. lt was even

served when women gathered to sew, quilt, or pick the

seedsoutofcotton. "

Liquor also owed at such public events as militia

The Alcoholic Reublic

musters , elections, and the quarterly sessions of the

courts. Militiamenelectedtheirofncers withthe expecta-

tion that the elected ofncers would treat. One newly

elevated colonel pledged, 'l can't make a speech, but

what l lack in brains l will try and make up in rum. '

Voters demanded and received spirits i n exchange for

their ballots. Electoral success, explained one Kentucky

politico, depended upon understanding that 'the way to

men's hearts, is, down their throats. " At trials the bottle

was passed among spectators, attorneys, clients~and to

thej udge. lfthe foremanofa jury became mellowin his

cups , thedefendantstoodanexcellentchancefor acquit-

tal.

Z

Alcohol was pervasive in American society, it crossed

regional, sexual, racial, and class lines . Americans drank

at home and abroad, alone and together, at work and at

20

A NATION OF DRUNKARDS

play,infunandinearnest. Theydrankfromthe crackof

dawn to the crack ofdawn. At nights taverns were nlled

withboisterous , mirth-makingtipplers . Americans drank

before meals, with meals, and after meals . They drank

while working in the nelds and while travelling across

halfacontinent. Theydrankintheiryouth, and, ifthey

livedlongenough, intheiroldage. Theydrankatformal

events, such as weddings, ministerial ordinations, and

wakes, and on no occasion~by the nreside of an eve-

ning, on a hot afternoon, when the mood called. From

sophisticated Andover to frontier lllinois, from Ohio to

Ceorgia, in lumbercamps and on satin settees, in log tav-

erns and at fashionable ew York hotels, the American

greetingwas, 'Come, Sir, takeadramnrst. 'Seldomwas

itrefused.

21

Early nineteenth-century America may not have been

'anationofdrunkards, ' butAmericanswerecertainlyen-

joying a spectacularbinge.

2 1

CHAPER

A GOOD CREATURE

Drink is in itself a creature of God,

and to be received with thankfulness.

INOREASE MATHER

1673

W M W

W W

JUNDERSTAND the great alcoholic binge of the early

nineteenth century, we have to go well back into the

eighteenth century to examine changes that were then

taking place. changes in the social structure, in philo-

sophical ideas, in business and industry, and, most par-

ticularly, in beliefsandhabitsrelatedtotheconsumption

ofalcohol.

At the beginning ofthe eighteenth century, tradition

taught, and Americans, like Englishmen and Europeans,

universallybelieved, thatrum, gin, andbrandywerenu-

tritious and healthful . Distilled spirits were viewed as

foods that supplemented limited and monotonous diets,

as medications thatcould cure colds, fevers, snakebites,

frostedtoes, andbrokenlegs, andasrelaxantsthatwould

relieve depression, reduce tension, and enable hard-

working laborers to enjoy a moment ofhappy, hivolous

camaraderie. Such favorable views led to a widespread

useofstrongdrink. Before 1750 nearly all Americans of

all social classes drank alcoholic beverages in quantity,

somenmestothe pointofintoxication.

Virginia slaves, at the bottom of the social scale, in-

dulged insuchfrequent intoxicationthatonegovernorof

the colonywas persuaded to oher his servants a bargain.

lftheyagreedto stay sober on the Queen's birthday, he

promised that they would be allowed to get drunk an-

The Alcoholic Reulic

other day. His offer was accepted, and the bargain was

fulnlled. White laborers were also great imbibers, and,

accordingtodiaristWilliamByrd, theVirginiapopulace

got drunkregularlyat militia musters, on electiondays,

and during quarterly court sessions. The orth was as

giventodrinkasthe South. OneewEnglanderwrote:

There's scarce a Tradsman in the Land,

That when from Work is come,

But takes a touch, (sometimes too much)

O Brandy or of HuD.

Even on the western frontier, rum was a dietary staple.

WhenWilliamByrd'spartysurveyedthe Virginia-orth

Carolina boundary, one backwoods host served them a

dinneroffat bacon soaked inrum.

or was heartydrinkingconnnedtothe lowerclasses.

At auctions in Philadelphia it was the custom to serve

liquor to any merchant who made a bid. On one oc-

casion, the bidders drank 20 gallons of rum while the

total sales came toless thanzoo. Diarist Byrd recorded

many instances ofintoxication among the Virginia elite

and particularly noted a doctor friend who frequently

came drunk to dinner.` Another physician who drank

freelywas Dr.|ohnPotts. WhilegovernorofVirginiahe

continued a medicalpracticethatconsistedprincipallyof

prescribing distilled spirits for his patients and himself.

There was lIttle opposition to such robust drinking.

While WilliamByrddidnotcondonepublicdrunkenness

that led to disorder, he expressed equal indifference to-

ward intoxication among members of the Covernor's

Council and among his own servants. He considered oc-

casional drunkenness a natural , harmless consequence of

imbibing. At that time inebriation was not associated

with violence or crime, only rowdy, belligerent inebria-

tion in public places was frowned upon. Such excesses

were discouraged in part by the high price of distilled

l

A GOOD CREATRE

spirits andinlarerp

.

art

.

byth

factthattheupper class

.

es

monitored pubbc dnnkmg. Smce all classes ofcolomal

society had the same attitude toward drinking and the

same easygoing drinkingstyIe, upper class efforts to re-

strain public drunkenness were, on the one hand, made

in a tolerant spirit and, on the other, accepted as neces-

sary for thepreservationoforder.

That the upper classes were able to monitor drinking

and to impose restraints was due to the hierarchical na-

ture of colonial society. Although men were deemed

equal beforethe law and before God, theirsocialandpo-

litical inequalities were recognized and respected. ew

Englandersfollowedtheadviceoftheireducated, socially

prominent Congregational clergy, and in free and o

P

en

elections they chose men from the upper classes as tith-

ingmen, schooloverseers,townselectmen

;

andlegislative

representatives. ew York's Hudson River valley pa-

troons not only demanded but received their tenant

farmers' support, and further south, Virginia planters,

whose prestige was based on owning vast acreage

nd

numerous slaves, vied only with each other for election

tothe House ofBurgesses.

One wayi nwhich the upper classes monitored drink-

ing was bycontrollingthe taverns. During the nrst half

oftheeighteenthcenturythepublichousewasa focu

of

community life. Americans met there not only to enjoy

themselves but also to transact business and debate poli-

tics . ln Virginia, for example, where the law a|lowed

only one tavern per county, this drinking place most

often adjoined the courthouse. Before trials it was com-

mon for defendants, attorneys, judges, and j urymen to

gathertheretodrink, andsometimesmatterswere

.

settled

'out ofcourt. ' At other times, when a controversial case

attractedacrowd, itwasnecessarytoholdthetrialinthe

tavern, which was the only public building roomy

enough to accommodate the spctators. ew England

27

The Aloholic Reublic

public houses were often built next door to meeting

houses so that Sunday worshippers could congregate

there before and after service. During the winter,

churchgoers warmed their posteriors in front ofthe tav-

ern nre a

d their interiors with rum before yielding to

the necessity of entering the unheated meeting house.

Afterworship, theythawedout atthetavern.

Becausetaverns played such an important role in local

affairs , the upper classes believed that they should be

well regulated, orderly, and respectable, that only men

and women of good moral character should operate

them, and that this requirement could best be met

through the device of licensing. ln late seventeenth-cen-

tury Massachusetts, for example, the law provided that

onlyvotersandchurchmembers, thecolony's elite, were

eligible tohold licenses. Suchregulations led tothe kind

of situation that existed in the town of Danvers, where

the licensed taverners included two deacons and an or-

dained Congregational minister. Even when members of

the upper classes did not themselves manage the public

houses, the licensing system kept publicans subservient

tothe townorcounty authorities who held thepowerto

grantordeny permits.

Yet licensing itselfwas only one mechanism by which

the upper classes asserted their authority. Control was

also exercised through informal channels . One Mas-

sachusettsministerinsistedthatapublichousebelocated

nextto hisowndwellingsohecould monitortaverntraf-

nc through his study window. lf he observed a man

frequenting theplace toooften, theclergyman could go

next door and escort the drinker home. Ministers , how-

ever, were not the only men ofauthority who enforced

li

uor regulations. ln i ; i , for example, some holiday

rinkersrefus

d toleavea Bostonpublichouseatclosing

time, and their denance was broughtto the attenton of

)udge Samuel Sewall. Thej udge immediately left home

I

A GOOD CREATURE

and proceeded to the tavern. There he 'Found much

Company. They refus'd to go away. Said were there to

drink the Queen's Health, and they had many other

Healths to drink. Call'd for more Drink. drank to me, l

took noticeofthe Affrontto them. Said mustand would

stay upon that Solemn occasion. Mr. |ohn etmaker

drank the Queen's Health to me. l told him l drank

none,uponthatheceas'd. Mr. BrinleyputonhisHatto

affront me. l made him take it off. l threaten'd to send

some ofthemto prison,thatdid not movethem. . . . l

told themiftheyhad nota care, theywould beguiltyof

a Riot. " With that warning the drunken mob departed.

Although Sewall had not found it easy to disperse the

men, their capitulation underscores the reality ofupper

class controlofthe taverns.8

This hearty, carefree, freewheeling, benign drinking,

monitored and to some extent controlled by the upper

classes, would probably have prevailed indennitelyifthe

per capita consumption of distilled spirits had remained

stable. All signs, however, indicate that rum drinking

increased after i ;zo. or was this increase surprising,

for the priceofdistilled spirits fell. At Boston the price

ofa gallonofrumplummetedfrom shillings6 pencein

i ;z z to z shillings in i ;8. At that low price a common

laborer could afford to get drunk every day. Ceorgians

were no more sober than Bostonians. ln i ;, when

|ames Oglethorpe investigated delaysintheconstruction

of a lighthouse, he leared that workmen labored only

one dayinseven, for a day'swageswould buy a week's

inebriation. Lower prices had naturally stimulated de-

mand. Boston rum production rose substantially during

the i ;os, andinthefollowingdecadeewEnglandim-

ports ofbothrumand molassesfordistillationincreased.

By the middle ofthe century, Boston, Providence, ew

Haven, and Philadelphia had emerged as centers of a

burgeoningdistillingindustry."

The Alcoholi Reublic

This high tide ofrum brought with it a new style of

drinking. Public drunkenness became a vehicle for the

expression of anger and hostility. lt also became evident

tosomepeoplethatdrunkennessledtothievery, lechery,

and brutality. The association of rum with crime and

disorder caused these Americans to perceive inebriation

itselfasa majorsocial problem. ln i ; 6, when Benjamin

Franklin reprinted an English article against liquor, he

added a preface in which he said, Perhaps it may have

asgoodanEffectintheseCountriesasithad inEngland.

And there is as much ecessity for such a Publication

here as there, for our RUM does the same Mischiefin

proportion, astheir CEEVA. "

Among the nrst to be alarmed by the increase of

drunkenness and alcohol-induced disorder were, as we

might expect, American clergymen. Evangelist Ceorge

Whiteneld condemned inebriation, and troubled ew

Englandministers bewailedtheiniquities befallingCod's

Saints. This apprehension about alcohol, provoked by

extensive public drunkenness, contrasted with a more

restrained traditional Puritan view. ln the late seven-

teenthcenturythe Rev. lncreaseMatherhad taughtthat

drink was a good creature of Cod" and that a man

should partake ofCod's gift withoutwasting or abusing

it. Hisonlyadmonitionwasthatamanmustnotdrinka

Cup of Wine more then is good for him. " Only a few

years later, however, andevenbeforecheaprumhadhad

itsfulleffect, his sonwasexpressinga less serene view.

1

ln i ;o8 Cotton Mather afnrmed his father's teaching

that rum was a Creature of God, " that spirits had nutri-

tional and medical value, and that people could drink

moderately to gain strength. Drunkenness, however, he

condemned. Mather saw inebriation asa source ofsocial

unrest, as a sign ofdivine amiction, and as a warningof

eternal damnation. He had causefor alarm, for intoxica-

tion among Cod's Saints was not uncommon. What the

I

|

l

!

f

|

r

i

l

k

A Goon CREATRE

[uritan Mather feared especially was that the Flood of

R\M" would Overwhelm all good Order among us. "

By this he did not mean simply that intoxication would

lead to increased crime, pauperism, gaming, and whor-

ing. The Order"he fearedfor wastheclassstructureof

ewEnglandsociety. Rum, hebelieved,was a threatto

the existing social merarchy. The menace that Mather

feared was a consequence ofthe intertwining ofpopular

beliefsaboutthevirtueofthegoodcreaturerumwiththe

rising availability ofthat cheap, plentiful beverage. ln a

cultureinwhichliquorwasrespected, itsusewaslimited

only by how much people could afford. The source of

Mather's alarm was that the wealthy elite, whom he ad-

dressed, could best afford to buy rum and were, there-

fore, the mostlikelyto overindulge.

To Mather, upper class inebriation had frightening

consequences. The Votaries ofStrong Drink, " he warned,

will grow numerous, . . . they will make a Party,

againsteverything thatisHol, and Just, and Go

d. " oci-

ety was threatened by a tide of upper class mebnates

who would sweep away the authority ofthe righteous,

thechurchwould yieldtothe tavern, the ministertothe

barkeeper. This upheaval would lead to new valus

throughout thehierarchyuntil the day came when chil-

drencalledfor theirdramsand awifebecame"Mitress of

a Bottle. " This unnatural and unrighteous society would

thenbepunishedby Cod. Therewas,however, one

ay

to prevent this catastrophe. The higher ranks ofsociety

must renounce drunkenness in order to be a model for

the rest. Let persons oftheBest Sort, be Exemplary for

this pieceofAbstinence; andthen, "he predicted, Lette

Lowest o the People, beinthatpoint, we'll consent untoit,

A Good 0 the Best. " Thus would the 'good order' be pre-

served.

Z

Whatever effect Mather's warnings may have had in

ewEngland, itisclearthatelsewherethe upperclasses

Th Aloholic Reubli

continuedtodrinkheartily. Forexample,in i ;, nearly

two decades after Mather's death, when Dr. Alexander

Hamilton ofAnnapolis recorded histravelsthrough sev-

eral colonies, he rated cities and regions by their ow of

spirits. Hewasdisappointed inPhiladelphia's lowrateof

consumption, buthe disliked evenmorethe poorquality

ofewEngland's beverages. Thatregion, hewrote, pro-

videdbetterforhorsesthanfor men. Whenvisitingew

York, hefound thata reputationforhearty drinkingwas

essential for admission to the best society. On one oc-

casionhe matched bumperswithCovernorCeorge Clin-

ton, whom he fondly labelled a jolly toaper. " He en-

joyed the high quality ofthe drinks served him in ew

York but deplored the efforts ofew Yorkers to make

him intoxicated byproposingtoomanytoasts. Dr. Ham-

iltonpreferred moderation to excess~not more than one

bottleofwine eachevening.

Centlemen who by reason of their wealth, prestige,

and popularity setthe tonefor society belongedtodrink-

ingclubsthatmetprivatelyinthebackroomsoftaverns.

Theseretreats, modelled after the Londonclubs immor-

talized by Samuel |ohnson, ourished in cities such as

Charles Town, ew York, and Annapolis. Dr. Hamil-

ton's club inAnnapolis had nfteen witty, raucous, fun-

loving members who put away at each weekly meeting

not less than a quart of Madeira wine apiece. While

Hamilton and his friends downed expensive, imported

Madeira, poorer Americans were drinking more and

more cheap, domesticrum.

One ofthe early consequences ofcheaper, more plen-

tiful rumwasthattheupperclasses beganto losecontrol

ofthe taverns. Astheprice fell, people were able to buy

more spirits, andthisincreaseddemandattractedapleth-

ora ofnew purveyors. lnthecities there beganto appear

manysmallprivatedealerswhosoldspiritstofriendsand

neighbors wimout l icenses, in Boston it was reported

'' : : *: ' "' ' ` *`""

A GOOD CRETRE

Dr. Hamilton's Sketch

ofthe Tuesdy Club.

By perisin u the

Maryland Historicl

Society, Baltimor.

that liquor could bebought atone ofevery eight houses.

lnthe hopeofretaining some measureofcontrolandau-

thority, public ofncials were driven to increasing the

number of permits for pubIic houses. ln Boston the

number of licensed premises rose from ;z in i ;oz to

i in i ; z . Although this rateofincreaseonly slightly

exceeded the rate by which he city's population had

grown, the largernumber ofpublic houses proved to be

more than the upper classes could watch effectively.

The Alcoholic Reublic

Taverns are multiply'd amongus,`complained Thomas

Foxcron, beyond the bounds of real ecessity, and

eventoa Fault, ifnot a Scandal.`

The proliferation of weakly controlled licensed public

houses led eventually to efforts to have the number of

permits reduced. ln I ;6o, at Braintree, Massachusetts,

|ohn Adams launchedone such crusade. He arguedthat

taverns andinns, whichwerenecessaryfortravellers and

town people on public occasions, were otherwise nui-

sances, that too many permits had been granted, so that

publicans, inordertoreapa pront, wereforced to sell to

immoral people, and that the licensing oftavern keepers

selected from among the mostworthy had given way to

licenses for the multitude. The public, however, favored

a liberal licensing policy, and when Adams asked the

Braintreetown meetingtoconsider reducingthenumber

ofpublic houses, he wasridiculed.

embers ofsociety's upper classes, having failed in

their efforts to reduce the number of licensed taverns,

then sought to impose stricter laws for their regulation.

Mea

ures were enacted to discourage Sunday sales, to

require all taverns to provide lodging for travellers, to

evoke licen

if gaming were permitted on the prem-

ises,to prohibit sales to seamen, andto stopa slave from

buyingliquorwithout hismaster'sconsent. Theseprovi-

sions, judging from their frequent modincations and

reenactments, failedto stopthe erosionofupper class au-

thority. By the middle ofthe century, when the upper

classes found that they were no longer able to control

public houses, many agreed with Franklin'sPennsylvania

Gazette, March z, i ;6, that taverns were a Pest to

Society.`

To those who presumed that they had the right to

mold society's institutions, the unregulated tavern's in-

dependence, likethegrowing independence ofthe lower

classes, was a sign ofchaos and disorder. Men such as

3

4

A GOOD CRATUR

|ohn Adams came to blame public houses for the weak-

ening ofreligious inuence and the creation of political

factions. Adams complained that a clever politician who

cultivated publicans would win the support of the

masses, thattaverngoers in many towns were a majority

ofthepopulace, andthatdrinkinghouses werethe nur-

series of our legislators .` Among the articulate, taverns

had few defenders, although Hunter's Virginia Gazette,

|uly z, i ;z, did print an article warning that license

regulations that frustrated the common people in their

Pursuit of lndependence` from upper class control

would lead themto feelcrushed byAuthority.`

Whetheror not taverns werenurseries` ofthe legisla-

tures, they were certainly seed beds of the Revolution,

the places where British tyranny was condemned, mili-

tiamen organized, and independence plotted. Patriots

viewed public houses as the nurseries of freedom, in

frontofwhichlibertypoles were invariably erected. The

Britishcalled thempublic nuisances and thehot beds of

sedition. There is nodoubtthatthe success ofthe Revo-

lution increased the prestige of drinking houses. A sec-

ondeffectofindependencewasthatAmericans perceived

liberty from the Crown as somehow related to the free-

dom to down a few glasses ofrum. Did not both free-

doms givea mantherighttochoosefor himself? Upper

class patriots found it difncult aftertheRevolutionto at-

tack the popular sentiment that elite control of taverns

wasanalogoustoEnglishcontrolofAmerica. Asaconse-

quence, drinking houses emerged from the war with in-

creased vitality and independence, and the legal regula-

tionoflicensed premiseswaned."

While opposition to the taverns developed and then

collapsedinthethroesofthe Revolution,upperclassatti-

tudes toward liquor were undergoing change. By the

middle ofthe eighteenth century many educated people

had begun to doubt that spirituous liquor was ever a

3 5

The Aloholic Reublic

good creature, and some begantocondemnit altogether.

This changeofmindwasstimulated bya numberofim-

pulses, among which were the spread of rationalist phi-

losophy, the rise of mercantile capitalism, advances in

science, especially the science of medicine, and an all

pervasiverejectionofcustomand tradition. ltwasatime

whenmenhad begunto thinkofthe worldinnewways.

They expressed the hope that rather than depending

uponfaith andcustom mankind wouldprogressthrough

the capacity of the human mind for reasoning and the

acquisition of knowledge. Many ofthose imbued with a

rationalist philosophy were opposed to drinking because

theyconsidered thatthegratincationto behad fromtak-

ing spirituous liquor was more than offset by its detri-

mentaleffect onthe reasoningprocess .

Mercantile capitalists opposed the use of spirits for

practical reasons. They had developed far-nung business

empires byemployingnew, improved business methods:

theyevolvedbetterbookkeepingpractices,tookonlylim-

ited risks, calculated their risks more accurately, shared

their risks through mutual insurance, and settled for

smaller but surer pronts. Businessmen whose fortunes

were based on these more precise methods commonly

tradedinrum, buttheycametoviewtheextensiveuseof

rum or any other distilled spirits by their employees,

agents,orbusinessassociatesasathreattotheircommer-

cial success. '

We should notbesurprised tonndthatamongthenrst

Americans to condemn the use of distilled beverages

were the Quakers, a sect whose members were not only

educated and reform minded but also mercantile ori-

ented. AnthonyBenezet, the bestknownearly opponent

ofspirituousliquors,wasawealthyPhiladelphia Quaker.

He had extensive commercial connections and was well

aware of the conditions necessary for the successful

operation ofa modern business. lmbued with the spirit

A GOOD CRATUR

ofreform, he was drawnto advanced positions ona vari-

etyofsocial questions . Todayhe isbestremembered for

his hostility to slavery and for starting a movement that

led to the emancipation of northern bondsmen. How-

ever, hewas no less hostiletodistilledliquor andduring

the Revolutionattacked bothrumand slavery, which he

j ointly characterized in one pamphlet as The Potent Ene

mies o Amerca. He argued that the Revolution's success

inendingBritishrulewouldbeahollowvictoryifAmer-

icans failed to rid themselves ofthese twin evils. A re-

public offree men, he contended, had no place for the

bondageofmeneither toothermenortodistilled spirits,

Americans must liberate themselves from customs that

impededthenation'sdevelopmentasahavenforfree, ra-

tional men. Hereforthenrsttime we see liberty viewed

ina newlight, notasa man'sfreedomtodrinkunlimited

quantities of alcohol but as a man's freedom to be his

own master, withtheattendantresponsibilitytoexercise

self-control , moderation, andreason.

Starting early in the eighteenth century, long before

the adventofBenezet, Quakershad begunto practicere-

straint in the use of distilled spirits, and this restraint

increased through the years . ln i ;o6 the Pennsylvania

Yearly Meeting advised Friends not to drinkeven small

quantities of distilled liquors at public houses. ln i ;z6

Quakers were forbidden to imbibe spirits at auctions.

Quafnng theauctioneer's liquor, it was reasoned, raised

the cost of the goods being offered for sale; in other

words , such self-indulgence fostered bad business prac-

tices. At mid-century, when other Americans drank

heartilyatmnerals, Quakercustomcalledforpassingthe

spiritsbottleonlytwice. Evenrestrainedusecameunder

attack, nrst by Benezet and later by the Pennsylvania

YearlyMeeting,which, duringawartimebread shortage

ini ;;;, ordered Friends neithertodistillgrainnortosell

grain to be distilled. Aner the war, there were new re-

; ;

The Aloholic Reublic

strictions: in i ;8 Friends were neitherto import nor to

retaildistilledspirits,in i ;88notto use liquor asa medi-

cine without caution, in i ;8 not to use distilled bever-

ages at births, marriages, or burials. By the i ;8os

Quaker opposition to all drinking of spirituous liquors

waswidespreadand vigorous.23

During the eighteenth century Methodists were the

only other principal religious denomination that shared

the Quakers' oppositionto distilled spirits. Many ofthe

Methodists, unlike the Quakers, were uneducated and

lowerclass people who werelittle induenced by the rise

ofrationalist philosophy, science, or business efnciency.

Their hostility to liquor arose from two other sources.

First, all innovative, new movements have a need to as-

sertthemselves by rejectingtradition. ThustheMethod-

ist remsal ofthe customary dram was in itselfa radical

act symbolizingthe new sect's determination to rootout

old customs and habits. Second, founder |ohn Wesley

represented a peculiar rationalism, expressed in his goal

torestructurereligionthrough'method. ' Methodists saw

the drinking of spirits as a hindrance to the process of

reordering and purifying both the church and society.

mrican

.

eth

.

odists joined the Quakers in condemning

distilled spntsm the i ;8os, long before tradition-bound

Baptists and Presbyterians.24

While rationalist philosophy, commercialism, and the

rejection of tradition were inuential in changing atti-

tudes toward distilled spirits, it was the new, scientinc

approach to medicine that had the greatest effect. As

early as the i ;zos some scientists had concluded that

alcohol was poisonous, and by the i ;os this view was

gaining support. |ames Oglethorpe, for example, at-

tempted to banrum fromhis Ceorgia colony atthe urg-

ing of the Rev. Stephen Hales, one of the colony's

trust

es, a physiologist, and the authoroftwoantispirits

treauses. Then, during the i ;os, American doctors

A Goon CREATURE

be

antoin

estigateth

quaintlynamedWestlndies Dry

Cnpes. This was a pamful, debilitating malady that we

now r

cognize a

lead poisoningcaused by drinkingrum

made m lead snlls. Contemporaries were puzzled until

Philadelphia's Dr. Thomas Cadwaladeridentined rumas

the cause ofthe disease and recommended abstinence a

novel proposal that was contrary to traditional opinin

concerning rum's healthful qualities.25

People opposed to liquor for any reason soon recog-

nized that the health argument was the most potent

weaponi

theirarsenal. ThatwaswhyAnthonyBenezet

cloaked is moral and philosophical opposition to spirits

bydevotmgmostofhisantiliquortractstoarecitationof

diseasespurportedlycausedby strongdrink. Thislineof

attack was encou

aged by the medical theories being

taught at the Edmburgh College of Medicine, where

Benjamin Rush, who wasto leadthe post-Revolutionary

campaign against distilled spirits, studied in the i ;6os.

To men captivated bythe Enlightenment spirit, the dis-

covery

.

that a too

xtensive consumption of alcohol pro-

d

ceddlnessanddiseasehadtwoimportantimplications.

First, th

informatio

itselfwas a signofprogress, a sign

ofthe tnumph ofrattonal, experimental inquiry overir-

rational tradition and custom. Second, the realization

that alcohol was detrimental to health would becertain

.

1

it seemed, to lead men to abstinence and, as a conse-

quence, to rationality.26

s early

.

as i ;; z , Rush, by then a physician living in

hilad

.

elphia, condemned distilled spirits in a pamphlet

m which he urged moderate drinking, eating, and exer-

cise. ln this work, addressed to the upper classes, he

argued for the right of physicians to propose new

theories. He hoped that the 'same freedom ofenquiry'

could b extended to medicine, which has long pre-

vailed in religion. " This attack on orthodoxy resulted

from Rush's scientinctraining. His Edinburgheducation

39

The Akoholi Reublic

had led him to question the dogma that alcohol was

healthful . ln fact, he had concluded from observing his

patients that spirituous liquor was a powerful stimulant

that destroyed the body's natural balance. Although he

noted in his pamphlet the potential dangers to health

caused by immoderate drinking, his conclusions were

tentative, and he did not at that time recommend ab-

stinence. Despite the inconclusive nature ofhisnndings,

he published the work and sent two copies to !ondon,

one to a bookseller for republishing and the other to

Benjamin Franklin, who was then a colonial agent in

England.

The doctor's conviction was strengthened during the

Revolutionary War when he served for a time as the

Continental Army's surgeon general . The army's tradi-

tional rum ration, Rush asserted, caused numerous dis-

eases, particularly fevers and uxes. Thepoorhealthof

American soldiers contrasted with the vigor and vitality

ofthe warriors ofthe Roman Republic. Their canteens,

he incorrectly andperhaps naively stated, hadcontained

nothing but vinegar.` Rush's wartime experience and

medical ideals drove him in r8z to write 'Against

Spirituous Liquors. 'Thisnewspaperarticleurgedfarm-

ers not to supply their harvest laborers with distilled

spirits, which, he claimed, failed to aid physical labor,

injured health, crippled morals , and wasted money. As

substitutesheproposed various mixtures compounded of

milk, buttermilk, cider, small beer, vinegar, molasses,

and water.

These early works showed a growing hostility to dis-

tilled spiritsthatculminatedin Rush's i ;8essay,An In

quir into the Efcts ofSpirituous Liquors. This piece, nrst

published as a newspaperarticle andthenasapamphlet,

combinedincompactformtheargumentsthatthedoctor

had encountered and those he had employed in his long

antiliquorcrusade. Hecatalogued liquor'sdefects. itpro-

A Goon CRATR

e

cted against neither hot nor cold wea

.

ther, for on hot

days it overstimulated and on cold ones itproduced te-

orary warmth that led to chills; it caused numerous ill-

essesstomach sickness, vomiting, hand tremors,

Jropsy, liver disorders, madness, alsy, apoplexy, and

epilepsy. Spirituous liquor, he beheved, should be

.

re-

placed withbeer,lightwine,weak rumpunch, sourmlk,

or

switchel, a drink composed of vin

gar, sugar,

.

and

water. The pamphlet was a masterpiece. l

s rational

arguments, logic, andincisive examples madeit boththe

century's most effective short piece and also a model for

later temperance publications; by i 8

more

.

tan

i ;o, ooocopies had beencirculated. Evenm i ;8its im-

pact was such that enthusiastic readers wrote Rush ad-

miring letters . From frontier Pittsbu

gh

gh H

ry

Brackenridge reported that he had quit dnnkmg spnts,

andfrom Charleston Dr. David Ramsayannounced that

he had arranged for Rush's unpopular' views to be re-

printed inthelocal press. "

. . .

Why, we might ask, was this particular article s

ch a

success? For one thing, Rush showed an extraordmary

capacityfor marshallingtheevi+ence to suppo

t his con-

victions. His skillful presentation of the subject, how-

ever, does not fully explain why the Inquir produced

such a sympathetic and vigorous response. The doctor

seems to have struck a public nerve, and his success de-

pended far less upon his lterar

)

t

lnt

.

and skill as a

propagandist than upon his

.

scientic ideals. By

.

the

i ;8os, Rush's medicaland socialteonesa+passed mto

the mainstream ofeducated Amencan opinion. Whereas

his training at Edinburgh had once

ad

his

.

medcal

views the object ofsuspicion, by the eighties his ,ehefs

were respectable, even fashionable. lntelhgent, articulate

people agreed with Rush that b

dly imbalances caused

disease, thatthedutyofthephysicianwastorestorebal-

ance, and that the most effective remedies were purga-

Th Alcoholic Reubli

tives and bleeding. Then, too, as a highlyregardedmedi-

calpioneer, Rushwasable, unlikeotherdoctors, toargue

new propositions convincingly. o man understood his

opportunities better than Rush, who assailed liquor in

the belief at this point that physicians could serve the

cause better than ministers orlegislators.30

Weshouldnot, however, attributetheInquir's success

solely to Rush's preeminent position in medicine, his

s

.

killful presentation, and the receptive mind ofthe pub-

hc, for much of its appeal to readers was

erived from

the author's sociology. To understand how the doctor's

iliquor pamphlet had employed a new methodology,

it is necessary to consider two ofhis other essays, An

Account ofthe Manners ofthe Cerman lnhabitants of

Pe

nsylvan

.

ia"andAnAccountoftheProgressofPopu-

lation, Agriculture, Manners, and Covenment in Penn-

sylvania. "Theformer was a pioneeringworkincultural

anthropology, the nrst analysis of American ethnic as-

similation. The latter was an equally original contribu-

tion to sociology, a brilliant account ofhow distinct so-

cial classes succeeded one anotheron theAmericanfron-

tier. Both pieces employed a new analytical method.

Whereas the usual technique in an eighteenth century

pamphlet had been toproceed from lists ofobservauons

to an analyt

.

ical conclusion, Rush employed a two-step

approach. First, he arranged data in categories, each of

which he analyzed, then, in a secondstep, he compared

the results ofthese analyses and arrived at a conclusion.

ln Cerman lnhabitants, "he nrstanalyzed the mores of

Cerman Pennsylvanians and the mores ofEnglish Penn-

syIvanians and then compared the results of these

analysesandconcludedthatinterminglingwouldeventu-

ally diminish ethnic differences. ln Progress ," an

analysis of each ofthree types of frontier social classes

led to an examination of how one cIass would displace

another. TheInquir followed the samemethod in pro-

l

A Goon CRATU

ceeding from preliminary analyses of the several

tategories inwhich distilledspirits wereshowntobeun-

to a masterly summary in which Rush con-

_Iudedthat abstinence was imperative.31

TheInquir' s popularityled Rushtoembarkonacam-

paigntospreaditsmessage. Followingitsnrstprintingin