Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Civilazation and Capitalism 15th-18th Century. Volume 1 - Fernand Braudel - 0023

Uploaded by

Sang-Jin LimOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Civilazation and Capitalism 15th-18th Century. Volume 1 - Fernand Braudel - 0023

Uploaded by

Sang-Jin LimCopyright:

Available Formats

Introduction

W h e n , i n 1952, Lucien Febvre asked me to write this book for the collection Destins du Monde (World Destinies) which he had recently founded, I had no idea what an interminable venture I was embarking upon. The idea was that I should simply provide a summary of the work that had been done on the economic history of pre-industrial Europe. However, not only did I often feel the need to go back to the sources, but I confess that the more research I did, the more disconcerted I became by direct observation of so-called economic realities, between the fifteenth and the eighteenth centuries. Simply because they did not seem to fit, or even flatly contradicted the classical and traditional theories of what was supposed to have happened: whether the theories in question were Werner Sombarts (1902, and backed up by a wealth of evidence) or Josef Kulischers (1928); or indeed those of economists themselves, who tend to see the economy as a homogenous reality which can legitimately be taken out of context and which can, indeed must, be measured on its own, since nothing is intelligible until it has been put into statistics. According to the textbooks, the development of pre-industrial Europe (which was studied quite exclusively of the rest of the world, as if that did not exist) consisted of its gradual progress towards the rational world of the market, the firm, and capitalist investment, until the coming of the Industrial Revolution, which neatly divides human history in two. In fact, observable reality before the nineteenth century is much more com plicated than this would suggest. It is of course quite possible to trace a pattern of evolution, or rather several kinds of evolution, which may rival, assist or at times contradict one another. This amounts to saying that there were not one but several economies. The one most frequently written about is the so-called market economy, in other words the mechanisms of production and exchange linked to rural activities, to small shops and workshops, to banks, exchanges, fairs and (of course) markets. It was on these transparent visible realities, and on the easily observed processes that took place within them that the language of economic science was originally founded. And as a result it was from the start confined within this privileged arena, to the exclusion of any others. But there is another, shadowy zone, often hard to see for lack of adequate historical documents, lying underneath the market economy: this is that elemen tary basic activity which went on everywhere and the volume of which is truly fantastic. This rich zone, like a layer covering the earth, I have called for want of a better expression material life or material civilization. These are obviously ambiguous expressions. But I imagine that if my view of what happened in the

23

You might also like

- Sweet Sweetback's Badasssss Song. The Watts Festival, Meanwhile, BroughtDocument1 pageSweet Sweetback's Badasssss Song. The Watts Festival, Meanwhile, BroughtSang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- 1 - 0082 PDFDocument1 page1 - 0082 PDFSang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- 1 - 0079 PDFDocument1 page1 - 0079 PDFSang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- 1 - 0080 PDFDocument1 page1 - 0080 PDFSang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- 1 - 0081 PDFDocument1 page1 - 0081 PDFSang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- 1 - 0078 PDFDocument1 page1 - 0078 PDFSang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- The Crying of Lot 49: Sunshine or ?Document1 pageThe Crying of Lot 49: Sunshine or ?Sang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- 1 - 0072 PDFDocument1 page1 - 0072 PDFSang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- 1 - 0076 PDFDocument1 page1 - 0076 PDFSang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- 1 - 0073 PDFDocument1 page1 - 0073 PDFSang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- 1 - 0074 PDFDocument1 page1 - 0074 PDFSang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- 1 - 0063 PDFDocument1 page1 - 0063 PDFSang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- 1 - 0075 PDFDocument1 page1 - 0075 PDFSang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- 1 - 0066 PDFDocument1 page1 - 0066 PDFSang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- 1 - 0064 PDFDocument1 page1 - 0064 PDFSang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- 1 - 0071 PDFDocument1 page1 - 0071 PDFSang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- 1 - 0067 PDFDocument1 page1 - 0067 PDFSang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- City of Quartz: The SorcerersDocument1 pageCity of Quartz: The SorcerersSang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- 1 - 0060 PDFDocument1 page1 - 0060 PDFSang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- Amerika, Echoed Adamic in Its Savage Satirization of Make-Believe LandDocument1 pageAmerika, Echoed Adamic in Its Savage Satirization of Make-Believe LandSang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- 1 - 0069 PDFDocument1 page1 - 0069 PDFSang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- 1 - 0068 PDFDocument1 page1 - 0068 PDFSang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- 1 - 0062 PDFDocument1 page1 - 0062 PDFSang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- Hollers Let Him Go (1945), Is Noir As Well-Crafted As Anything by Cain orDocument1 pageHollers Let Him Go (1945), Is Noir As Well-Crafted As Anything by Cain orSang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- 1 - 0056 PDFDocument1 page1 - 0056 PDFSang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- 1 - 0058 PDFDocument1 page1 - 0058 PDFSang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- Noir Under Contract Paramount Gates, Hollywood: Sunshine or ?Document1 pageNoir Under Contract Paramount Gates, Hollywood: Sunshine or ?Sang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- American Mercury Announced The Genre, Los Angeles Noir Passes IntoDocument1 pageAmerican Mercury Announced The Genre, Los Angeles Noir Passes IntoSang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- California Country Are Absent Los Angeles Understands Its Past, InsteadDocument1 pageCalifornia Country Are Absent Los Angeles Understands Its Past, InsteadSang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- 1 - 0057 PDFDocument1 page1 - 0057 PDFSang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- 3.5G Packages - Robi TelecomDocument2 pages3.5G Packages - Robi TelecomNazia AhmedNo ratings yet

- Survey On Dowry SystemDocument2 pagesSurvey On Dowry SystemRajiv Kalia62% (26)

- People of The Philippines Vs BasmayorDocument2 pagesPeople of The Philippines Vs BasmayorjbandNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of FactDocument3 pagesAffidavit of FactMortgage Compliance Investigators100% (8)

- Torbela Vs Sps RosarioDocument2 pagesTorbela Vs Sps RosarioJoshua L. De Jesus100% (2)

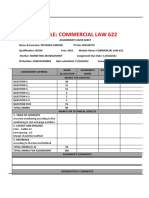

- Claw 622 2022Document24 pagesClaw 622 2022Priyanka GirdariNo ratings yet

- General Dyer CaseDocument3 pagesGeneral Dyer CasetimNo ratings yet

- Glory To GodDocument2 pagesGlory To GodMonica BautistaNo ratings yet

- Mediation Script.Document2 pagesMediation Script.AdimeshLochanNo ratings yet

- CLIFFORD PROCTOR'S NURSERIES LIMITED - Company Accounts From Level BusinessDocument7 pagesCLIFFORD PROCTOR'S NURSERIES LIMITED - Company Accounts From Level BusinessLevel BusinessNo ratings yet

- University of Rajasthan Admit CardDocument2 pagesUniversity of Rajasthan Admit CardKishan SharmaNo ratings yet

- ALBAO - BSChE2A - MODULE 1 (RIZAL)Document11 pagesALBAO - BSChE2A - MODULE 1 (RIZAL)Shaun Patrick AlbaoNo ratings yet

- 2022 P6 Maths Prelim NanyangDocument52 pages2022 P6 Maths Prelim NanyangAlbert Hein Nyan HtetNo ratings yet

- Investment Phase of Desire EngineDocument21 pagesInvestment Phase of Desire EngineNir Eyal100% (1)

- Conflict of Laws (Notes)Document8 pagesConflict of Laws (Notes)Lemuel Angelo M. EleccionNo ratings yet

- JHCSC Dimataling - Offsite Class 2 Semester 2021 Summative TestDocument1 pageJHCSC Dimataling - Offsite Class 2 Semester 2021 Summative TestReynold TanlangitNo ratings yet

- TimeOut Magz - 50 Sexiest Songs Ever MadeDocument3 pagesTimeOut Magz - 50 Sexiest Songs Ever MadeRahul VNo ratings yet

- G12 Pol Sci Syllabus FinalDocument8 pagesG12 Pol Sci Syllabus FinalChrisjohn MatchaconNo ratings yet

- MBA Program SrtuctureDocument23 pagesMBA Program SrtuctureVaibhav LokegaonkarNo ratings yet

- Abm 12 Marketing q1 Clas2 Relationship Marketing v1 - Rhea Ann NavillaDocument13 pagesAbm 12 Marketing q1 Clas2 Relationship Marketing v1 - Rhea Ann NavillaKim Yessamin MadarcosNo ratings yet

- Lebogang Mononyane CV 2023Document3 pagesLebogang Mononyane CV 2023Mono MollyNo ratings yet

- Power of The Subconscious MindDocument200 pagesPower of The Subconscious Mindapi-26248282100% (2)

- The True Meaning of Lucifer - Destroying The Jewish MythsDocument18 pagesThe True Meaning of Lucifer - Destroying The Jewish MythshyperboreanpublishingNo ratings yet

- The Dawn of IslamDocument2 pagesThe Dawn of IslamtalhaNo ratings yet

- Arthur N. J. M. Cools, Thomas K. M. Crombez, Johan M. J. Taels - The Locus of Tragedy (Studies in Contemporary Phenomenology) (2008)Document357 pagesArthur N. J. M. Cools, Thomas K. M. Crombez, Johan M. J. Taels - The Locus of Tragedy (Studies in Contemporary Phenomenology) (2008)Awan_123No ratings yet

- Ac3 Permanent File ChecklistDocument4 pagesAc3 Permanent File ChecklistAndrew PanganibanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 11 - Cost-Volume-Profit Analysis: A Managerial Planning ToolDocument19 pagesChapter 11 - Cost-Volume-Profit Analysis: A Managerial Planning ToolSkyler LeeNo ratings yet

- NCERT Solutions For Class 6 History Chapter 7 Ashoka The Emperor Who Gave Up WarDocument3 pagesNCERT Solutions For Class 6 History Chapter 7 Ashoka The Emperor Who Gave Up Warunofficialbyakugun050100% (1)

- The Macabre Motifs in MacbethDocument4 pagesThe Macabre Motifs in MacbethJIA QIAONo ratings yet

- Program Evaluation RecommendationDocument3 pagesProgram Evaluation Recommendationkatia balbaNo ratings yet