Professional Documents

Culture Documents

7 - 1 - Week 7 Part 1

Uploaded by

CSF1Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

7 - 1 - Week 7 Part 1

Uploaded by

CSF1Copyright:

Available Formats

Welcome back, this is Week 7, the final week of our course.

Thanks so much for staying with me, I hope you have been enjoying it. I've been having a lot of fun. This lecture this week is an important one, it's about doing things. Doing things to improve population health with the social epidemiologic perspective. It's one of my favorite topics. It's also quite daunting. For this week I assigned four readings. I didn't want you to get off easy. These aren't too hard, fairly accessible, and I hope there's some interesting discussion about them on the discussion forum. I want to emphasize that what I'm going to offer you, offer in this week is just a snippet of things I know about for doing things with social epi. there is all kinds of ways this can be considered. And I'm only going to offer a little. So, I hope the discussion forums can enhance and elaborate on the stuff we get started with in this lecture. Of these three modules for this week, the first is background and let's do that today. This is one of my favorite quotes. It's apparently coming from, Mark Twain the American author who said everyone talks about the weather but no one does anything about it. And I think that's an important statement or metaphor for social epidemology. It is really important, sometimes, to learn about what causes disease. Is it a change in social capital? Is it some discriminatory practice? Is it a social policy? what's happening? So, learning what causes disease is critically important. But it's also important to think about how can we mitigate, remedy, or improve the health of populations. This is what we want to talk about in this week. And, it's a very difficult topic, but it's also, critically important. So, the basic question is, how may we use social epidemiology, to improve population health? Look at that. Ever seen Power Point do that? What can we do?

Well, let's start by going back to one of the original slides that we've done. And this is sort of that causation slide. We start with the big D, disease, on the right-hand side, and we say what caused the disease? Germs, genetics, biology, physiology. Absolutely true. These things certainly cause disease. What alters exposures, and sometimes even alters genes and even a body's physiology? Well, that's behaviors and lifestyle choices and other things in that dimension. But then we can ask yet another question. What causes behavior? Why are some exposed and others not? And that is the realm of social epidemiology. The cause of causes. These are things such as social forces, social norms, market power sexism, racism. All the things we've been talking about through the entire course. So, when you think about doing things, the question is where do we want to intervene? Where in this big chain should we put our energy? Should we alter genes? Should we give people medicines, maybe. And in some cases, yes. In other times, well, we want to alter lifestyles or behaviors, good idea. But social epidemiology's at it's best when we're working on the upstream, or the cause of the causes. Let's alter social norms. Let's alter regulatory policy to change who is exposed and who is not, to give incentives for others to be healthy. This is social epidemiology at its best. We also want to remember our old bathtub. Remember, things are more multilevel. The group affects the person who may or may not change. And that person reflects back or affects the group. This is the multi-level concept we've been talking about the whole class. I want to remind you that we talk about interventions. They are often at their best when they are multi-level. Of course, it's challenging to disentangle the levels, but that doesn't mean we ought not do things in a multi-level framework.

So, we want to intervene, we want to alter the social system to improve, usually not inhibit population health. Interventions, therefore, can be at the micro-level and this could be in terms of medicines, but who gets the medicines and how do they get it? That's a social epi question. It's one thing to have a vaccine, it's another to distribute it and have people actually use it. We can also do things at the meso level. This is the mid, middle level. Here we might be affecting family structures, doing things at local policy, as we discussed earlier in the course. And, of course, we can discuss things or do things at the macro-level. This might be state policy. It might be global trade policy, it can be changing social norms. So, this is where we want to focus our attention. What's interesting to note is the macro-level interventions tend to impact more people. They're macro, so there's more people in the path, if you will. But over time and over and over again we find at the micro-level, the individual level or sometimes even the biological interventions, tend to have more impact, on health for any given person. So, here's the great tension. Meso, or macro-level interventions affect a lot of people. Micro-level interventions seem to work better. What can we change in the social system? Lots of things. And I'm sure you have your own ideas. We can educate persons of all places, all kinds females especially, in the developing world. This tends to have profound impact on population health. Of course, we can alter policies and laws, that might be corporate policies. Of course, they could be governmental policies. They might even be within household policy. Who does the laundry? Who does the dishes? We can certainly try to affect social norms. Social norms, again, are like policies, but they're not written down. And if you want to understand a social norm, just do something that's sort of

confronts your social network's way of doing things. And you'll get that look, perhaps that ostracization that will make you sort of step out of the group. That's the power of a social norm. Of course, we can also affect physical environments, move the toxic dump, change where the nuclear plant is, plant trees. These kinds of things are also upstream, and can be certainly conceived as, social epi-interventions. One note of caution, it's easy for particular, particularly people newer to the discipline, to think we can make everyone like each other. Here is a painting, of course, of a Garden of Eden scene. And one the troubles is, we think we can solve all society's problems if we just change these norms or just alter the policy. The data don't support that, of course. It's tough to get people to behave well and to like one another. When we think about interventions, I want to emphasize, it's critically important to demonstrate that such interventions doing things has an impact. That in fact, it can be demonstrably or scientifically shown to have done something. This can create tensions. We've got a great idea to improve heatlh, but if you can't show that it worked, people don't take it seriously. So, we want to have good evaluations or assessments of the things we're doing. One of the critical ideas in this kind of evaluation work comes from a late scholar named Peter Rossi, who wrote a wonderful chapter, actually, called The Iron Laws of Social Program Evaluation. So, Professor Rossi had worked for decades in trying to understand the impact of social policies here in America to improve health, to improve things like poverty. And of course, this was happening in the middle and late 1960s. And what Rossi came up with a bit tongue in cheek was what he called the Iron Laws of Program Evaluation. The important, first one is, the expected, measurable impact, of any large scale social program is zero. Rossi was not personally happy about this conclusion, but after three or four decades of work, he had to conclude that large scale social im, impact evaluations

tend to show no effect. Not all of them, just on average. Further, he goes on, the more rigorous an evaluation, the better study, the more likely a chance of finding no impact. So, the better the study, the more likely we see the truth. And finally, the more a program attempts to change people, and I'll say, adult people. If we're trying to change an adult person, change their behavior, stop smoking, wear a seat belt, wear a bike helmet, these kinds of things, the better chance is you're going to have no result. Changing adult persons behavior is very difficult. Rossi encouraged us researchers to work in what he called Policy Space. By this he meant, try to imagine interventions that don't give us the Garden of Eden, but in fact, work on ideas that can actually be implemented by your local community, by your regional government, by the federal government, if you want to. What can really be done, given the political and social context, it's unlikely we're going to get everyone to like each other and cooperate fully. Instead, what can actually be done, and this is the idea of policy space. It can be limiting but it also keeps us near the closest possible world assumption that we've talked about in the discussion of counter factuals. Well, how do we alter social norms? It's very difficult, but I came across this newspaper or website article a few days back and it really struck me. Here, the idea, and I think this applies mostly for the American audience, of why is it that young men, typically young men, I suppose, are supposed to give a young woman of their choosing. And maybe she chooses, him a diamond engagement ring? Where did the social norm for giving a diamond engagement ring come from? And this website from Business Insider, and you have the link here, has a fascinating story about why diamonds aren't actually rare. How the De Beers company bought up all the diamonds and make them rare through monopoly power. And then, did marketing in the 1920s and 30s to, say, if you loved your fiance and wanted to marry her, you should, you ought to, give her a diamond ring.

And so, here, we have, if you will big business altering social norms. And they're very good at it. That's the point of marketing, of course. Another fascinating social norm to think about is what's sometimes called Chinese foot binding, or foot binding in general. And you may know the story. for a thousand years many persons, were, in certainly China, were having, females, were having their feet bound up. Crushed, actually. And this was a result of some desire to improve social status. And the idea was one could improve their daughter's social status to help her marry up, if you will, by having her feet bound. And, why did this take off? Because lots of people wanted to have their daughter marry up. So, this practice, this rather brutal practice, went on for 1,000 years. But it was overturned, in fact, in one generation. So, 1000 years of practice the norm of foot binding was overturned in one generation. How? It's a fascinating story, in brief, the parents of girls said we will not bind our girls' feet. And the parents of boys said we will not let our son marry a girl with bound feet. And pretty soon, poof. That social norm was absolutely turned on its head. Some great research comes from Gerry Mackie. This is the American Sociological Review. It's not assigned, you may be interested. There's some also interesting things on the internet. Another way to alter behavior. We can alter people's information. One way that's being done in America more recently is to have calories, calories of foods available for purchase at fast food restaurants. So, here, we see an example of, of menu, bored from, some arbitrary fast food restaurant. And next to it is not only the price, but how many calories this product is. This, in this case, salmon club sandwich on a croissant. It sounds good. But it's 770 calories. So, the idea is, if you tell people more information, they will behave

differently. Unfortunately, this effort does not seem to have much of an impact. Here's a review paper from the Robert Wood Johnson, Robert Wood Johnson's Healthy Eating Research Group. And it's in June 2013. And it's a summary in which says that the impact of menu labeling is ambiguous. Some studies show as small impact, other studies show as no impact. What's fascinating to me is this work conforms exactly to Rossi's rule. The better studies, better quality studies methodically show no impact, a fascinating tale. Well, no effort for doing things in social epidemiology would be complete without talking about the change in cigarette smoking use or the prevalence or incidence of cigarette smoking. And this graph is going to be difficult to see. But as most of you probably know, in America and the western world, the prevalence, or incidence, depending on how you want to talk about it of cigarette smoking has declined precipitously from what was 60 and 70% of the population down to about 20. That's a massive change, it used to be as many of you know that it was the smokers right, if you will, to smoke. And persons who didn't like it didn't want to say anything. That social norm is entirely flipped in America today, where now the non-smokers hold the social norm power. A smoker needs to ask permission. That's again in about one generation. Fascinating impact. However, the social norm has not been flipped in every country. And it's going to be impossible for you to see these graphs, but the, on the horizontal bottom axis, this is just countries. And the point of this is that by country, smoking prevalence still is high, and it varies widely. So, the social norms haven't changed everywhere. That's the important point. So, when we talk about doing things in social epi, want to think about smoking, want to think about food consumption. want to think about how marketers use marketing strategies to say encourage men to buy diamond rings. This is doing stuff in social epi.

[SOUND].

You might also like

- The Social Determinants of Health KLDocument22 pagesThe Social Determinants of Health KLCSF1No ratings yet

- 6 - 5 - Week 6 Part 5Document5 pages6 - 5 - Week 6 Part 5CSF1No ratings yet

- Socialepi-readings-week7-Oakes 2009 - Improving Community Health For BYI - FINALDocument38 pagesSocialepi-readings-week7-Oakes 2009 - Improving Community Health For BYI - FINALCSF1No ratings yet

- Oakes FullChapterDocument40 pagesOakes FullChapterCSF1No ratings yet

- 7 - 1 - Week 7 Part 1Document8 pages7 - 1 - Week 7 Part 1CSF1No ratings yet

- 6 - 4 - Week 6 Part 4Document9 pages6 - 4 - Week 6 Part 4CSF1No ratings yet

- 7 - 3 - Week 7 Part 3Document7 pages7 - 3 - Week 7 Part 3CSF1No ratings yet

- 7 - 2 - Week 7 Part 2Document6 pages7 - 2 - Week 7 Part 2CSF1No ratings yet

- 5 - 4 - Week 5 Part 4Document5 pages5 - 4 - Week 5 Part 4CSF1No ratings yet

- 6 - 1 - Week 6 Part 1Document7 pages6 - 1 - Week 6 Part 1CSF1No ratings yet

- 6 - 2 - Week 6 Part 2Document6 pages6 - 2 - Week 6 Part 2CSF1No ratings yet

- 6 - 3 - Week 6 Part 3Document6 pages6 - 3 - Week 6 Part 3CSF1No ratings yet

- 5 - 2 - Week 5 Part 2Document7 pages5 - 2 - Week 5 Part 2CSF1No ratings yet

- 5 - 3 - Week 5 Part 3Document5 pages5 - 3 - Week 5 Part 3CSF1No ratings yet

- 4 - 1 - Week 4 Part 1Document6 pages4 - 1 - Week 4 Part 1CSF1No ratings yet

- 3 - 3 - Week 3 Part 3Document6 pages3 - 3 - Week 3 Part 3CSF1No ratings yet

- 4 - 3 - Week 4 Part 3Document5 pages4 - 3 - Week 4 Part 3CSF1No ratings yet

- 5 - 1 - Week 5 Part 1Document5 pages5 - 1 - Week 5 Part 1CSF1No ratings yet

- 4 - 4 - Week 4 Part 4Document6 pages4 - 4 - Week 4 Part 4CSF1No ratings yet

- 4 - 2 - Week 4 Part 2Document9 pages4 - 2 - Week 4 Part 2CSF1No ratings yet

- 2 - 2 - Lecture 2 Part 2Document5 pages2 - 2 - Lecture 2 Part 2CSF1No ratings yet

- 3 - 2 - Week 3 Part 2Document4 pages3 - 2 - Week 3 Part 2CSF1No ratings yet

- 3 - 1 - Week 3 Part 1Document5 pages3 - 1 - Week 3 Part 1CSF1No ratings yet

- 2 - 1 - Lecture 2 Part 1Document4 pages2 - 1 - Lecture 2 Part 1CSF1No ratings yet

- 1 - 3 - Lecture 1 Part 2Document7 pages1 - 3 - Lecture 1 Part 2CSF1No ratings yet

- 2 - 3 - Lecture 2 Part 3Document5 pages2 - 3 - Lecture 2 Part 3CSF1No ratings yet

- 1 - 4 - Lecture 1 Part 3Document6 pages1 - 4 - Lecture 1 Part 3CSF1No ratings yet

- 1 - 5 - Lecture 1 Part 4Document5 pages1 - 5 - Lecture 1 Part 4CSF1No ratings yet

- 1 - 2 - Lecture 1 Part 1bDocument7 pages1 - 2 - Lecture 1 Part 1bCSF1No ratings yet

- 1 - 1 - Lecture 1 Part 1aDocument5 pages1 - 1 - Lecture 1 Part 1aCSF1No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- 300307814sherlin SapthicaDocument100 pages300307814sherlin SapthicaTitin PrihartiniNo ratings yet

- GDS - Goldberg's Depression ScaleDocument2 pagesGDS - Goldberg's Depression ScaleAnton Henry Miaga100% (1)

- MCGRW HL S Npte M Dutton BK PDFDocument1,311 pagesMCGRW HL S Npte M Dutton BK PDFJack DowNo ratings yet

- Philamcare V CADocument1 pagePhilamcare V CAOscar E ValeroNo ratings yet

- Tooth EruptionDocument6 pagesTooth EruptionDr.RajeshAduriNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Community HealthDocument15 pagesFactors Affecting Community HealthAngela SernaNo ratings yet

- Pubs/behres/bcr4theo - HTML Pada 26 September 2011: Daftar PustakaDocument22 pagesPubs/behres/bcr4theo - HTML Pada 26 September 2011: Daftar PustakareinzhordNo ratings yet

- History Wellness and MassageDocument34 pagesHistory Wellness and MassageAldrin Balquedra-Cruz Pabilona67% (3)

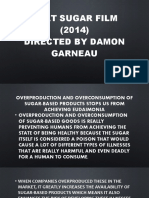

- That Sugar Film (2014) Directed by Damon GarneauDocument7 pagesThat Sugar Film (2014) Directed by Damon GarneauBai Fatima LumanggalNo ratings yet

- Symptom Differences Between Zika, Chikungunya and Dengue FeverDocument4 pagesSymptom Differences Between Zika, Chikungunya and Dengue FeverHnia UsmanNo ratings yet

- GMC Handwara Recruitment 2023Document4 pagesGMC Handwara Recruitment 2023Ummar WaniNo ratings yet

- Work at Height Supervisor Course MandarinDocument6 pagesWork at Height Supervisor Course Mandarinpanel1bumyj3100% (2)

- The Social Norms ApproachDocument7 pagesThe Social Norms ApproachJasmine TereaNo ratings yet

- Liv.52 TabletsDocument2 pagesLiv.52 TabletsSYED MUSTAFANo ratings yet

- Pediatricstatusasthmaticus: Christopher L. Carroll,, Kathleen A. SalaDocument14 pagesPediatricstatusasthmaticus: Christopher L. Carroll,, Kathleen A. SalaAndreea SasuNo ratings yet

- HR Report For Handing OverDocument19 pagesHR Report For Handing OverSimon DzokotoNo ratings yet

- Lesson 6 Sexual Health Hygiene 1Document9 pagesLesson 6 Sexual Health Hygiene 1Nikka GoenettNo ratings yet

- Dri - English - 113 Driver Risk InventoryDocument6 pagesDri - English - 113 Driver Risk Inventoryminodora100% (1)

- Mo2vate Issue 15 - March 2022Document74 pagesMo2vate Issue 15 - March 2022Mo2vate MagazineNo ratings yet

- FARC-01 - Senior First Aid (Occupational First Aid Course OFAC)Document2 pagesFARC-01 - Senior First Aid (Occupational First Aid Course OFAC)Ewien Vars SianturieNo ratings yet

- Structural Family Therapy Versus Strategic Family Therapy: A Comparative DiscussionDocument11 pagesStructural Family Therapy Versus Strategic Family Therapy: A Comparative DiscussionDavid P Sanchez100% (8)

- Review Process of Discharge Planning: by Janet BowenDocument11 pagesReview Process of Discharge Planning: by Janet BowenAfiatur RohimahNo ratings yet

- Debeb, Simachew Gidey, Et Al. 2021Document13 pagesDebeb, Simachew Gidey, Et Al. 2021priya panaleNo ratings yet

- Himachal StatsDocument115 pagesHimachal StatsVikrant ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- Student Nurses' Community: Nursing Care Plan PneumoniaDocument2 pagesStudent Nurses' Community: Nursing Care Plan PneumoniaNur SanaaniNo ratings yet

- Table 4-8 - Switching AntidepressantsDocument1 pageTable 4-8 - Switching AntidepressantsDragutin PetrićNo ratings yet

- Thompson & Thompson Genetics in Medicine Genetik EthicDocument21 pagesThompson & Thompson Genetics in Medicine Genetik EthickartalxyusufNo ratings yet

- Modified Hemorrhoidal Artery Ligation Malang Procedure As An Alternative Therapy in Management of Haemorrhoid Grade IIIDocument4 pagesModified Hemorrhoidal Artery Ligation Malang Procedure As An Alternative Therapy in Management of Haemorrhoid Grade IIIInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- HIV/AIDS Education GuideDocument12 pagesHIV/AIDS Education GuideDutch EarthNo ratings yet

- Meditation and Energy HealingDocument16 pagesMeditation and Energy HealingCristian CatalinaNo ratings yet