Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Duration of Unemployment and Unexpected Inflation - An Empirical Analysis

Uploaded by

Aadi RulexOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Duration of Unemployment and Unexpected Inflation - An Empirical Analysis

Uploaded by

Aadi RulexCopyright:

Available Formats

No.

24, 1980

THE DURATION OF UNEMPLOYMENT AND

UNEXPECTED INFLATION - AN EMPIRICAL

ANALYSIS

by

Anders Bjrklund and Bertil Holmlund

June 1978

Revised August 1979

This paper has been accepted for

publication in the American Economic

Review.

l. lntroduction*

A distinguishing message of the theory sea unamploy-

ment is that short-run unemployment fluctuations are explain-

able by surprises. Unemployment is basically

viewed as productive investment in job search, chosen by employ-

ees in order to enhance their lifetime earnings. An increase 1n

aggregate demand will imp1y a temporary fall lin unemployment

due to short-run deviations between actual and expected wages;

workers are faoled into accepting more employment.

Th; s information-l ag interpr'etat ion of changes in unemp 1 oyment

might be compared to an alternative view, where the quantity-

rationing rules of the labor market are emphasized. A rising

aw of abor ft'om unemp l oyment to emp l oyment i s, accordi ng to

this theory, caused by the relaxation of job-rationing con-

straints rather than unanticipated inflation.

In this paper we address ourselves to the question of the

empirical importance of the two competitive explanations. The

two stories are, of course, not mutually exclusive; we try,

via a fairly simple specification, to capture both views in

one equation. The principal contribution of our study lies

in its ability to provide information about the relative

importance of unexpected inflation and job opportunities as

explanations of the duration of unemployment. l Another in-

teresting feature of our paper is its comparative per-

spective; we app same model to both Swedish and U.S.

data, thereby being able to reveal certain important dif-

ferences between the labor markets in the tilJa count es. ~ e

find e.g., perhaps somewhat surprisingly, that the U.S. un-

employment duration is more or less unaffected by unexpected

inflation, whereas the results for Sweden, on the other hand,

give some support for the information- is.

2

novelty of our study ;s the disaggregated data used (for Sweden

only). By focussing the analysis on transition probabilities

for workers with different lengths of (incompleted) spells,

same interesting behavioral differences are observed; one

fi is s e information-l story is more valid

for the short-term unemployed.

The paper is organized as fol1ows: Section II below introduces

the basic theoretical framework that guides Gur empiricai

estimation procedures; the latter are described in section III.

Section IV presents the data employed and section V the empiri-

cal results. Some interpretations of Dur findings are discussed

the final ian.

II. Optimal Search Policies and the Duration of Unemployment

Microeconomic explanations of unemployment have been focussing on

the behaviour of the household, whereas the demand side generai-

ly has been eonsi as exogenous. We will follow that rtial

equilibrium approach, using a simple job search model as our

theoretical framework.

Consider the behaviour of an unempioyed worker according to

$ e an

3

which assures him an income greater than what he might have

received by continued search. The decision is affected by

the perceived location of the wage offer distribution. If

a monetary contraction produces a left-ward shift of the

wage offer distribution - or a lower rate of wage inflation -

this change in general market conditions is assumed to be

imperfectly detected by job seekers, who mistakenly blame

local circumstances rather than changes in aggregate demand.

Unemp 1 oyed ltIorkers wi 11 search a longer time causing

l ength of spe 11 s unemployment to rise.

A common assumption in standard search models is that the

number of job offers received per period equals one. The pro-

bability of leaving unemployment - the transition probability -

is then sol ely determined by the job seeker's offer-acceptance

probability. The simplifying job offer assumption is, however,

tion the case with random number of job offers is easily in-

corporated into the b a s i ~ search theoretic framework. Consider

the job-seeker's transition probability, which - in the absence

of labor force exits - equals the hiring probability. Decompos-

ing the transition 1

.

l ~ ) into two components the

job offer probability (8) and the acceptance probability (P)

we have

(1 ) ]J = ep = 8[1-F(a)J

8 S.

- where a is the reservation wage and F(o) the distribution

4

function of wage offers. If the transition probability is

eons tant during search, the expected duration of unemploy-

ment (D)i s

( 1

Which are then the characteristics of an optimal search

policy? In the simple case of infinite time horizon and no

diseounting) the n t

variant reservation wage obtained as the solution to

GO

(3)

c = 8P[E(wiw>a)-aJ = ej(w-a)

a

where C is the (constant) marginal search cost and f()

known density function of wage offers. L. Eq. (3) imp!ies

that the reservation wage declines as the job offer probabi-

lit Y e decreases. Likewise, a known leftward shift of the

wage offer di bution 11 a l so reduce res on

vJe have so far br; efly outl ined the bas ie search story, str; ct-

ly valid only in a stationary world. Now consider the possibili-

ty of fluctuations in aggregate demand, influencing the job-

seekerls transition probability via the job offer probability

(more vacancies) and/or via imperfect reservation wage adjust-

ments. Three different effects may be identified:

Li' i numoer of vacancies

means a higher job offer probability, thereby reducing the dura-

5

tion of unemployment.

2. A permanent increase of the job offer pro-

bability will increase the expected returns from search, thus in-

creasing the workerIs reservation wage. It follows that the un-

employment effect of a rising number of vacancies is ambigous

a p n (1977) , demonst the

availability effect will outweigh the supply effect under cer-

tain reasonable assumptions.

affect location of the wage offer distribution. Assuming

a lag in the d,iscernment of a rising rate of inflation, reserva-

tion wages will be unaffected in the short run, implying a ris-

ing flow of new hires from the pool of unemployed.

Summarizing these three effects we have:

(4 ) II = 8(V)P(V ,w/w*) == g(V

+ +

where V is the number of vacancies, w the actual average wage

and w* the expected average wage.

We would argue that Eq. (4) represents the kernel of the search

theory of cyc1ica1 unemployment. The standard search model out-

lined does rely on some very restrictive assumptions, e.g. a

stationary wage offer distribution, fixed leisure time and a con-

stant job offer probability. More complex search models, e.g. those

Siven (1979) and Seater (1977, 1978

10

1...1 ) are, however, fairly

6

r is on

3

unexpected inflation and vacancy contacts. We are suppressing

other plausible determinants of unemp var-

htions in unemployment compensation and the discount rate.

These simplificat should not be too severe, since the cy-

clical uctuati na:t i We have also

excluded changes in the pr;ce level from consideration, perhaps

a more questionable simplification. Unexpected price inflation

does affect unemployment in same models within the microfounda-

tions literature, although it is absent in the standard search

v:ition regressor is, however,

quite different in e.g. the Lucas-Rapping model compared to

the Siven model (rnisperception of future prices versus mis-

perception of current prices) and the theoretical predictions

are completely opposite; a higher rate of unexpected price in-

flation will increase unemployment in Siven's model and decrease

1

4 .

unemployment in the Lucas-Rapping mode. It 1S interesting to

uni G rescnts 0.

tions in unemployment are totally unaffected by how workers

5

\.if: i ..... c

to ude

"""' ....-

the price inflation variable from the regressions, thereby

avoiding troublesome problems of interpretation.

III. Empirical analysis

A straightforward method of investigating the validity of the

detection-l hypothesis is to specify explicit transition pro-

bability equations with vacancies and unexpected wage increases

as explanatory variables, i.e. to represent Eq. (4) above by a

suitable functional form. The basic specification used will be:

(5) xn]l

v t

The obtained a

2

-estimate reflects the net result of the

positive availability effect and the negative supply effect;

7

intuition and some theoretical predictions suggest that a

2

(the

net availability effect) will have a positive sign.

6

The main problem with the approach chosen is, of that it

an ana is as \;Je 11 as nce

no direct data about expected wages or wage-changes are available

some model of the formation of expectations must be used. The ex-

panding literature about the formation of expectations give sever-

al alternatives which all are quite plausible. However, no model

v/hich can made operati can be considered ;jcorrect

H

'in a l

respects. Our approach has been to try three different models in

order to investigate how robust the information-lag-hypothesis

is with respect to the different specifications. Two of the ap-

plied forecasting functions are.consistent with the idea that

workers 1 earn past reestimating the parameters of

their forecasti equations when more information is obtained.

The first model used is a type of adaptive expectations. These

expectations are formed according to a finite distributed lag

of past wage changes, i.e., wi

for ):

(6a)

4

= l:

i

quarterly data (which is used

w .

9,. ( _)

l W 4'

t- -l

where

4

4

( Z

(5-i )

:::;

i == 1

i == 1

and viith monthly data (which is used for the U. S. )

w* 12 ItJ ,

(7a)

(t )

r_1

= L: Q,.

(. ~ ~ )

W l

t ~ 2

i = 1

v". ') .

~ l __ -l

where

12

l

12

(7b) E Q,. =

E (13-i) ==

1.

Models like these - where the sum of the weights has been

constrained to,vne - are of ten used in empirical work even

though ;t has been pointed out that the theoretical basis is

quite weak. ( e.g. Persson (1979), where it is shown that

the sum should equal one on1y in very special cases if the

forecast is to optimal. )

Even though the simplici of the simple adaptive model is

-. .

! ; ~ since it mi r-s

expectations in a simple and cheap way - 1t could also be argued

that individuals have some knowledge about historica1 regulari-

ties of wage changes, and that they use this information when

forming their expectations. One possible way to represent

these regularities is to apply a time-series approach. The as-

sumption is that people have in their mind an auto-regressive-

moving average-process (ARMA) which is generating forecasts from

9

ad to 80th s ficaticn e pe,r;;,mGters of

this process are, however, likely to be revised when peop1e re-

ceive more information about wage-changes. Therefore we have

proceeded as 1 Oi'/S:

The process has been reestimated each period and reidentified

each fourth period (with quarterly data) and each twelfth period

(with monthly data). 7 For Sweden the character of the process

changed over time; when observations from 1960 onwards were used

the appropriate process changed from an AR(l) to an AR(1)MA(2),

back again to an AR(l) and final1y - during the past two years

(1976-1977) - an MA(10) on the first differences of the variable

(i.e. the process was non-stationary). All the time autoregressive

seasonal terms had to be used.

For the U. S. the process \tIas stat; onary when data from 1960 un-

til 1969 were used.-AR(l) with first a seasonal autoregressive

term and then a seasonal moving average term. From then on the

process became non-stationary with an MA(l} term and a seasonal

moving average term on the first differences.

It could, finally, be argued that workers are still more rationa1

than using only from an ARMA-process of wage-changes.

They might even have in an empirical model incorporating

different economic variables. An unemployed worker forming his

10

expectations may e.g. use a wage-equation of the illips

curve ions

(quarterly data) like:

where

data from the last five years. On the whole the estimated equa-

tians performed reasonably wel1 for Sweden according to standard

This approach was less successful for U.S.; the available vacancy

indicators turned out to be bad predictors of wage inflation. We

to ude this expectations-formation scheme for the

U.S. regressions.

IV. The data

Swedish transition probabilities have been estimated as fol1ows:

The rotating system of the Swedish Labor Force Surveys is con-

structed so that almost 90 % of those who are interviewed in ane

survery are interviewed again three months later, whereas dif-

ferent individuals are interviewed in two subsequent manths.

In order to improve the estimates we decided to campute quarter-

ly transition p lities.

11

Oenoting the number of unemployed for at least a

less than b weeks at time t by and the weekly inflow

inta unemployment by f we can describe the estimates as follows:

1,14

13

(9) = f Z; ( l

)1

i =0

1 ')

]13

( 10) ==

[ 1

(11 )

G

27

,39

::::

r.:: 14,26 [ l _1 ] 13

t+26

\.:lt+13 11

3

Three transition probabilities are obtai

can be regarded as conditional upon the length of the spel1 of

unemployment. By using available data on f, etc.

from

( 12)

whereas

11

2

and 11

3

are calculated as

1/13

rG

14

,

27

1

(13 ) 1

I t I

Jl

2

::::

-

I

G

l,l3 ,

t t J

1/13

fG27,391

(14 )

Jl

3

::::

l

I t+26 i

-

I I

I G

14

, 26 I

l t+13 J

The Swedish vacancy statistics are from labor market statistics,

published by the National Labor Market Board. Quarterly wage data

are obtained from the labor market issues of Statistical Reports,

published by National Bureau of Statistics. All data used

to manufacturing industry.

The U.S. transition probabilities refer to the labor market

as a whole. They were computed by uSing the method proposed

Barror. (1 ). The essential idea is to campare the number

of people in one week who have been unemployed less than ve

weeks with the number of people four weeks later who have been

unemployed five to eight weeks. The difference consists of

people who have left the pool of unemployed. The duration data

reported in Ernployment and Earnings are grouped in the classes

12

1-4 weeks, 5-14 weeks etc., which requires a slight modification

out1i deta 15, see rran.

The U.S. wage data are average hourly earnings in manufacturing

'd t td' r l dE' SA d

111 repor e ln cmp oyrnent an arnlngs. s vacancy ata

for the period 1965-1 we used the Help-wanted advertising in-

dex (HWA) published in Main Economic Indicators (OECO). For the

period 1969.4-1973.10 manufacturing vacancies (Vm) according to

establishment data were also tried (Employment and Earnings);

the latter series are available only for (approximately) this

period.

V. rical results

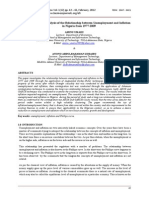

Tables 1 and 2 below. The estimation method is weighted-least-

squares and ate weights are derived in an appendix.

Let us first have a look at the results obtained for Sweden.

We observe, in the first place, that the detection-lag variable

is significant both for the short-term (1-13 weeks)

13

Table l. Transition probability equati9ns for

-Quarterly data 1968.1-1977.3

Adaptive expectations V w/w*

-2

R DW

( 1 ) 0.81 10:'30 0.60 1. 75

(4.29) Ut. 1O}

(2) 1.11 0.42 1. 57

(5.36)

l'":!. \

\v) 14. 0.41 1. 05

(5.18)

(4) 0.34 1. 97 0.33 2.27

(3.24) (1.69)

(5) 0.41 0.30 2.29

(4. 11 )

(6) 3.42 O. 16 1.84

(2.83)

(7) 0.39 -3.35 0.09 2.16

(2. 19) (-1. 57)

(8) 0.31 0.05 2.28

(1. 78)

(9) -L 0.004 2.03

(-0.93)

ARMA expectations

(10) 0.98 7.47 0.50 1.43

(4.94) (2.59)

(11 ) 11.00 O. 18 0.79

(3.08)

conto

ARMA expectations

v w/w*

-2

R DW

(12 )

(13 )

unemploved (11-)

(14 )

Expectations from wage-

equations

)

(15 )

(16 )

( 17)

(18 )

(19)

Nate:

R

2

.

1.8 the fraction of

0.36

(3.56)

0.36

)

1. 13

(5.93)

0.40

(4.23)

0.30

(1.72)

2.21

(L 64 )

3.56

(2.41)

-2.16

(-0.81)

8.43

(2.79)

7.76

(1. 85)

3. 10

(2.38)

3.37

(2.14)

-3.20

(-1.31)

0.33

O. 11

0.05

0.51

0.06

O.

0.09

0.07

the weighted variance of the

dependent variable explained by the weighted independent

2. 19

1.72

2.27

1.66

0.65

"

L.LI

1.63

2.20

-2 .

variables, adjusted for degrees of freedom. The R obta:i.ned

A

when regre8sing on 11

1

from Eq. (1) was 0.62.

14

15

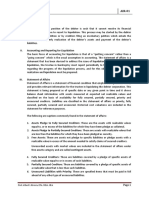

Table 2. Transition probability equation for the U.S.

Monthly data 1969.4-1973.10 and 1965.2-1975.12,

respectively

jl,daDt i ve

expectations HWA

Vm

w/w* TIME Fi

2

DW

P

1969.4-1973.10

--------------

0.23 1. 62 -0.0008 0.73 1. 19

(11.27) (1. 59) (-1.61)

2 0.21 0.91 -0.0002 n.a. 2.02 0.29

(8.57) (1.11) (-0.41)

3 0.24 1. 42 0.72 1.13

(11.81) (1. 38)

4 0.21 0.87 noa.

')

<-.

(8.71) (1. 08)

5 O. 14 -0.0021 0.07 0.37

(0.08)

! ';f"'" \

\

.:Jo;

6 0.50 1. 36 -0.0031 0.72 1. 18

(1. 33) (-6.39)

7 0.44 0.71 -0.0022 n.a. 1. 97 0.31

(8.21) (0.86) (-3.84)

8 0.45 0.21 0.51 0.67

(7.64) (0.15)

1965.2-1975.12

--------------

9 0.52 0.70 -0.0025 0.83 1. 34

(16.81) (1. 28)

10 O. 0.47 -0.0025 n.a. 2.03

0.34

(11. 45) (0.81) (-13.26)

11 0.49 1. 55 0.33 0.34

(7.93) (1. 43)

12 0.71 -0.0024 0.47 0.44

(0.73) (-10.62 )

conto

16

Adaptive

expectations HWA Vm w/w* TIME

-2

D ~ J R p

1969.4-1973.10

--------------

13 0.23 2.57 -0.0007 0.74 1. 15

(11.27) (2.07)

. , ~ 4)

(- I j .

14 0.20 1. 96 -0.0002 n.a. 2.03 0.30

(8.63) (1. 98) (-0040)

15 O. 2.48 0.73 1. 10

(11.92) (1. 98)

16 0.20 1. 93 n.a. 2.04 0.31

(

fl

';. ~ "-

17 0.24 0.71 1. 12

(11. 64)

18 0.20 n.a. 2.04 0.30

(8.68)

19 3.03 -0.0021 0.10 0.36

l 31) (-2.49)

20 0.49 ~ 4 8 -0.0030 0.73 1. 17

(11.23) (2.00) (-6.44)

21 0.44 1. 81 -0.0022 n.a. l. 99 0.30

(8.36) (1. 80) (-3.96)

22 0.44 2.23 0.53 0.65

(7.71) (1. 34)

1965.2-1975.12

--------------

23 0.52 -0.37 -0.0026 0.83 1. 33

(16.7) (-0.50) (-19.19)

24 0.53 -0.07 -0.0025 n.a. 2.04 0.35

(1 L 37) (-0.10) (-l3.01)

25 0.49 3.45 0.35 0.41

(8.03) (2.48)

26 -0.09 -0.0025 0.46 0.44

(-0.07) (-10.31)

Note: p is

the first-order autocorrelation coefficient obtained

by using the Cochrane-Orcutt approach.

17

and for the medium-term unemployed (14-26 weeks). These results

Q

hold for all models of expectations.

J

For the long-term unemployed,

on the other hand. no significant detection-lag effect is revealed;

the coefficient has even a wrong sign.

all regressions, even for the long-term unemployed. Dropping this

variable produces in most cases a marked decrease in the DW-value,

indicating the presenee of specification errors.

Which are then the economic interpretations of the different re-

sults for the three groups of unemployed? No straightforward

answer is available, partly because the "hypothesis-testing in-

cludes a joint test of the underlying model and the expectations-

la

generating mechanism

ll

The absence of any significant detection-

lag effect for the long-term unemployed may have at least two

and/or the variable reservation wage hypothesis could be errone-

DUS. There are arguments in favourof both these interpretations.

In the first p l c e ~ it makes sense to hypothesize that the 10ng-

term unemployed (more than six months in our data) are better

informed about the actual wage offer distribution, simply because

they have experienced a longer period of "learningll through full

tlme job search. This es

the forecasting function might differ across workers with dif-

ferent unemployment histories.

18

The second interpretation stated above (the possible unrealism

of the variable reservation wage hypothesls) may be elucidated

by recal1ing same familiar results from search theory: The re-

servation. wage of a job-seeker with finite search horizon will,

under some stationary conditions, fall with the duration of un-

emp1oyment, a theoretical prediction which has been given empiri-

cal support. llEventually the reservation wage will coincide with

the minimum value of the wage offer distribution, implying an

acceptance probabi1ity equal to one. In that extreme case a11

job offers are accepted and there is no detection-lag effect.

Both of the hypotheses outlined are consistent with the results

obtained. Intuition would suggest that both of the mechanisms are

in operation to same extent, reinforcing each other and thereby

producing the observed results.

Since both the (net) availability effect and the detection-lag

effect are significant, it is important to find out the relative

i ca 1

variations of the duration of unemployment. To find out this

of the independent variables inta account. The question might be

illuminated by comparing the predicted transition probabil ities

using estimates from regressions in the table

'"

( 15)

]Jt

=

al

.

V

t

.

(w*)

t

j

l ~

{, ~ '

r;ea eion is t- e:; .

,

perfectly foreseen (w

t

= w*)

t

(16)

a

2

]l = a . V

t t l

Using the results from the adaptive mode l Figure 2 below de-

monstrates the relative unimportance of the detection-lag

effect for the medium-term unemployed. Inflation surprises

produce, on the other hand, quite important unemployment effects

for the short-term unemployed during the peak years 1969-70 and

1974-75. (Figure 1.) The main part of the variation is, however,

attributable to the vacancy-variable.

Turning now to the U.S. regressions, the dominant avail lit Y

effect is even more pronounced than in the Swedish case. The

vacancy variables used are highly significant in all regressions

whereas the detection-lag coefficient is fairly sensitive with

respect to the choice of expectations mode l and pe-

riod. A significant detection-lag effect is obtained only by

applying an ARMA-expectations-generating mechanism for the pe-

riod 1969;4-1973;10. These results are independent of the choice

of vacancy variable. Exclusion of the latter alsogives rise to

a strong decline in the DW-statistic, indicating specification

errors. When the estimation period is extended (1965;2-1975;12),

the significance of unexpected inflation 12 It should

a1so be noted that a negative and significant trend-coefficient

is obtained when HWA is used as vacancy variable.

The main conelusian from these excercises on U.S. data is that

the job-availability variables are the dominant determinants of

19

20

Figure I. The effects of unexpected inflation - short-term unemployed

in Sweden

0.25 ~ .

0.20

I

r

i

\

i.-

I

L

\

I

0.15

!

I

t\

\

l-

I

L

l\

i

i

\

r

\

\

i I

O. 10

I

t

~

I

I

r

ti

0.05

'I

i

'" '

~ \

I

\=J

t-

o

I

,

. I I ! . I ; ,

. ! ! .

,

! . ! I ! i .

,

I

68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77

predicted transition probability

predicted transition probability when inflation is perfectly foreseen

21

Figure 2. The effects of

flation medium-term un

in Sweden

0.14

0.

06

1

----- ---------------:

T, i I t i t f , t r f i , t ; t f t , , I f I i I

68 69 70

]l

72 73 74 75 76 77

predicted transition probability

____ predicted transition probabi1ity when inflation is perfectly foreseen

however, rule out the possibility of same deteetion-lag ef-

feets in operation, at least during certain time-periods and

- espeeial1y - if the expectations are farmed according to an

ARMA-process rather than adaptively.

VI. Concluding remarks

job search literature there a tendency tu ove ook

22

the impartance of vacancy contacts as determinants of the dura-

tion of unemployment; the emphasis instead being placed on in-

flationary surprises. This (mis)use of the seareh stOt'y does not

necessarily follm'i from the 10gic of the theory; most search models

do recognize the significance of the stream of jab offers. The pop-

ularity of the detection-lag view is, probably, its ability to

provide a reasonable interpretation or the short-ruQ Phillips

curve. The transmission mechanism of aggregate demand policies is

explicated in a fairly simple ""ay: an increase in the money growth

rate \'1111 increase inflation thereby faoling the acceptance deci-

sions of job seekers.

In this paper we have that this ew has some empi cal

validity, at least for the short-term unemployed and forc alabor

market lika But we have also shown that unexpected in-

flation can explain only a small part of the actual fluctuations

in unemployment duration. Since the flovl inta unemployment is

fairly stable over the eyele. our results imply, moreover. that

cyclical changes in the unemployment rate are only sliqhtly affect-

ed by inflationary surprises.

23

The elementary search model - where variations in the job offer

probability are disregarded - is then clearly inadequate as an

curv so

rule out one of the mechanisms which imply a vertical long-run

Phillips curve; the natural rate theory must of course be valid

cyclical changes in unemployment. The results are thus more in

accordance with the II mainline

ll

view of inflation and unemployment

stressing that aggregate demand influences employment and unemploy-

ment via the relaxation of job rationing constraints rather than

via misperceptions of relative wages. It is possible that unanti-

cipated price inflation may be of some importance even with;n

the latter framework - as a determinant of the flow of vacancies

inta the labor market. We are, however, unaware of solid theoret-

ical work on that issue.

Let us, finally, offer some comments to the observed differences

ly unionized labor market and wage bargaining at the national

level gives rise to relatively uniform and long-term wage con-

tracts. One would be inclined to expect that this institutional

setting would produce fast dissemination of information about

the wages in general. thus reducing the importance of information-

lag effects. The less unionized U.S. labor market is probably

more r ~ l i o.r

13

than the Swedish is and the scope for temporary wage-mispercep-

tians would therefore be greater. In fact, we find the opposite.

ore itional significant di

24

labor market functioning in Sweden u.s. - the importance

of temporary layoffs. Temporary layoffs constitute - as Martin

14

Feldstein has out - an source of U.S. un-

employment. The U.S. manufacturing layoff rate has varied be-

tween 10 and 20 percent (of the number of employed workers)

per year whereas the corresponding Swedish figures are 2 - 4

percent. The major part (60 - 70 percent) of the U.S. layoffs

are temporary, implying that most workers are ultimately rehired

by the same employer. Temporary layoffs in Sweden are, on the

other hand, very unusual. Unemployed workers on temporary lay-

accounted r 2 - 3 percent of ish du ng

the period 1975-1978. The corresponding U.S. figures seem to have

fluctuated between la and 20 percent.

15

Feldsteinls view of those

laid off as liwaiting" rather than IIsearching" has been questioned

on empirical grounds.

16

The Feldstein-hypothesis mi.ght, however,

be considered as modest ly corroborated by our results; one in-

teresting interpretation of our revealed U.S.-Sweden differences

would be that the extent and intensity of job-search among the

unemployed is lower in the U.S. If unemployed workers on layoff

act as if they will be recalled - and therefore abstain from

search - there is little scope for detection-lag effects of

the traditional type.

A laid off worker IIhas a job" in some sense; he is attached to

a particular firm and expects to be recalled by his employer.

He is probably also we1l informed about wage changes in his firm.

How would then a non-seeking lmemployed worker on layoff respond

to unexpected general wage inflation? He would, most likely, be

25

inclined to search, s

fel1ows; a familiar implication of search theory is that quits will

decrease to sea as a response

to unexpected wage increases. Clearly, tempora layoffs re-

present a middle state between loyment and unemployment.

Economic theories designed to explain individual behavior

in the polar cases would obviously be less suitable when

applied to the middle state.

REFERENCES

R. Axelsson and K. G. Lfgren, IIThe Demand for Labor and Search

Activity in the Swedish Labor Market", Europ. Econ. Rev., 9,

19

J.M. Barron, "Search in the Labor Market and the Duration of Un-

employment: Some Empirical Evidence

il

, Amer. Econ. Rev" Dec. 1975,

65, 934-42.

T. F. Bradshaw and J. L. Scho 11, IIThe Extent of Job Search during

Layoff

ll

, Brookings Papers, Washington 1976, 2, 515-26.

Darby, "Three-and-a-Half Million U.S. Employees Have Been

fvtislaid: Or, and Explanation of Unemployment, 1934-1941

11

,

J. Polit. Econ., Febr. 1976, 84, 1-16.

14. Fel dstein, "The Importance of Temporary Layoffs: An Empi ri ca l

AnalysisIi, Brookings Papers, Washington 1975, 3, 725-44.

R. Feinburg, "Search in the Labor Market and the Duration of Un-

employment: Note

ll

9

Amer. Econ. Rev., Dec 1977, 67,1011-13.

R. Gronau, IIInformation and Frictional Unemployment"., Amer. Econ.

l 1. 1. 290-301.

H. Kasper, "The Asking Price of Labor and the Duration of Unemploy-

ment!!, Rev. Econ. and Statis. ) May 1967, 49, 165-72.

J.R. Kesselman and N.E. Savin, "Three-and-a-Half Million Workers

Never Were Lost", Econ. Inquiry, April 1978, 16, 205-225.

N.M. and G.R. Neuman, liAn Empirical Job-Search Model with/

a Test of the Constant Reservation-Wage Hypothesis

ll

, J. Po1it.

Econ., Febr. 1979,87,89-107.

S.A. Lippman and J.J. fvlcCall, II The Economics of Job Search:

A Survey: Part I!!!j Econ. Inquiry, June 1976, 14, 155-89.

R.E. Lucas, JR.and L.A. Rapping, "Real Wages, Employment and

Inflation", in S. Phelps et al. (1971), pp. 257-305.

C.R. Nelson, Time Series Anal Fore- ___ _________ =_ ___ __ __

casting

ll

, Holden-Day, San Francisco 1973.

M. Persson, Inflat ions and the Natural Rate

Hypothesis, Stockholm School of Economics (Diss.), 1979.

E.S. Phelps, "Introduction: The New Microeconomics in Employment

and Inflation Theory"., in E.S. Phelps et al. (1971), pp. 1-23.

et al, ilMicroeconomic Foundations of Employment

and Inflation Theory", !vlacmillan, London 1971.

J

Il

Off: A Critique of the Literature

ll

, J. Econ Lit., June 1978,

499-544.

J.J. Seater, ilA Unified Model of Consumptian, Labor Supply, and

27

"Util ity fv1aximizati on, Aggregate Labor Force Behavi or,

and the Phillips Curve

ll

, J. Econ., Nov. 1978, 4, 687-713.

, IIJob Search and Vacancy Contacts

ll

, Amer. Econ. Rev.,

June 1979, 69, 411-19.

North Holland, Amsterdam 1979.

H. Theil, "Economics of Information Theoryii, North Holland,

Amsterdam, 1967.

Arbetsmarknadsstyre 1 sen (AMS), II Arbetsmarknadsstati st; k ", (The

National Labor Market Board, lILabor Market Statistics

ll

), various

issues, Stockholm.

5,

Statistiska Centralbyrn (Se8), "Arbetskraftsunderskni

("Swedish Labor Force Surveys", AKU), yearly averages 1975-78.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), IIEmployment and Earnings",

various issues, Washington.

28

29

FOOTNOTES

* We are indebted to George Borts, Ned Gramlich, Mats Persson

and an anonymous referee for helpful comments on an earlier

vers; on.

1

The question has earlier beenadd ( 19

Axelsson and Lfgren (1977). Their methods differ from ours.

~ for a praof of (3), see e.g. ppman and Iv1cc,aii (19

\

) .

3

The worker in Sivenls

Seater's models is maximizing his

lifetime utility by using search in the labor market as one

important cholce variable. Siven a1so considers search in the

goods market but assumes leisure to be fixed; maximization of

the uti1ity functional is therefore equivalent to maximization

i earn; , on d, t ~ e s account

of variable leisure but ignores search on the goods market.

4

priceinflation implies in the Siven-model a re-

allocatian of time from search in the labar market to search in

the goods market thereby causing a decline of the job offer

probabiiity. The reservation wage will also increase} reinforc-

ing the effect on unemployrnent duration. The Lucas-Rapping mode 1

is hardly suitable for analyzing the length of spells of unemploy-

ment s it sregards j search and considers unemployment

as pure leisure, resulting as a difference between actual and

normal emp l 9 ) ana Kesselman-Savin (1978) have

run unemployment regressions for the U.S. including un-

anti ce i as an exp l anator'y va e.

results turn out to be unsatisfactory; the coefficients are

as a rule insignificantly different from zero and the signs

are unstable across di ressions.

5 Seater (1978).

6 The crucial trick in Barranis approach - fol1owed by Axe1sson

and Lfgren - is to construct a model which gives an explicit

s fication rel ip the il r es

(V) and offer probability (8). Given such a relationship,

8 = f(V), the acceptance probability is obtained as P =

re is interesti since i can validate a pro-cyclical

reservation wage pattern (i.e. P and Vare inversely correlated) .

.

The approach requires, however, some fairly restrictive assump-

tians regarding the relationship between e and V; Barron assumes

that 8 = k . V, implying that the elasticity equals one,

on

vacancy in each occupation. It can be shown that less restrictive

assumptions produce an elasticity lower than one. Barron's proce-

dure is, moreover, unable to separate the supply effect from the

detection-lag effect. Our approach, on the other hand, can quanti-

fy the detection-lag effect but captures only the net availability

effect.

7

A Box-Jenkins-program cal1ed T-series available at the Stockhoim

30

School of Economics has been used. For identification criteria, see

son 19 ),

31

8

In some regressions we a1so tried average hourly earnings for

l sector. The results were basical-

ly the same.

9

have also tried logit-specifications in same cases, as weIl

as adaptive expectations with shorter lags. The results turned out

to be fairly robust with respect to these changes.

10 Santomero & Seater (1978) p. 525.

11 See articles by Gronau 1 9 7 1 ) ~ Kasper (1967) and Kiefer &

( l

\

),

12 The coef+, ,'c,'ent f / *. " 'f" t" .... (25\ b t th

_ o w W l S S l gn, l can 1 n t.q., ) u e

value indicates that the t-ratio should not be taken s ously.

13 Phelps (1971) pp. 6-7.

14 See Feldstein (1975).

15

1\

(1975) figures imply that 18 percent of those unemployed in

!v1arch 1974 were on temporary 1 ayoff. The correspondi ng fi gure

for March 1978 is 11 percent (Employment and Earnings).

6

See the paper by & Scholl (1975) l10wing

discussion in the Brookings Paper.

APPENDIX

An estimation problem arises because the dependent variable

is an estimate of the Iitrueli transition probability. This

of i ~ ~ i ~ t to samo1ing

variation and this variation obviously enters in the regres-

sion equation as stochastic disturbances. Since this variation

is not constant the assumptions of ordinary least squares are

violated.

Thell (1 ) has rived the following variance of the dis-

turbances for the logit model:

(A. 1 )

where ~ l is the estimate of the transition probability and N

t

the number of observations. By using the same procedure as The;l

(see belo\'J)

(A.2)

The appropriate weights are given by l/Var(E? ).

_t

The derivation of (A.2) proceeds as follows: Consider the basic

relation bebJeen the IItrue

H

transition probability for individual

i at time t and the explanatory variable X

t

A: 1

A:2

(A.3)

Since the explanatory variables have the same values for all in-

dividuals in these applications index i has been omitted.

When the estimate V

t

of the death-risk is inserted inta the equa-

tion (A.3) instead of ~ t the sampling variation necessitates the

inclusion of a distrubance St

(A.4) ln" = ln

3 1 n

Now, the problem is to express the variance of St in terms of

The average of (A.3) is

(A.5)

By subtracting (A.5) from (A.4) we obtain:

(A.6)

- _1_ ~ (ln ]l - ln - I . ~

N

t

1. t l.L

The expression in parentheses can be simplified to:

(A.7)

The last expression can be simplified to

jl -]1.

8)

-"

if and other.

If (A.8) is inserted inta 6) we nave

(A.9)

The variance of Et now becomes:

(A. 10)

If as Theil, disregard var(]Jit) and approximate ']J by

we obtain:

(A.11 )

't

A:3

You might also like

- 2 PDFDocument15 pages2 PDFemilianocarpaNo ratings yet

- Paperdelectura (1) - 4-10Document7 pagesPaperdelectura (1) - 4-10kurt cutipaNo ratings yet

- Nber WorkingDocument42 pagesNber WorkingDushkoJosheskiNo ratings yet

- 2005 ShimerDocument87 pages2005 Shimertianfei.lyu.163No ratings yet

- Abowd Card 1986bDocument46 pagesAbowd Card 1986bStéphane Villagómez CharbonneauNo ratings yet

- American Economic AssociationDocument10 pagesAmerican Economic AssociationsaidNo ratings yet

- The Cyclical Behavior of Equilibrium Unemployment and Vacancies RevisitedDocument24 pagesThe Cyclical Behavior of Equilibrium Unemployment and Vacancies RevisitedmonoNo ratings yet

- Macroeconomics 1 - Chapter FiveDocument38 pagesMacroeconomics 1 - Chapter FiveBiruk YidnekachewNo ratings yet

- Gibbons and Katz, Layoffs and Lemons PDFDocument31 pagesGibbons and Katz, Layoffs and Lemons PDFVer Madrona Jr.No ratings yet

- MIT Graduate Labor Economics 14.662 Spring 2015 Note 2: Job Loss and Job Search at The Micro and Macro LevelDocument19 pagesMIT Graduate Labor Economics 14.662 Spring 2015 Note 2: Job Loss and Job Search at The Micro and Macro Levelarati.kundu.1943No ratings yet

- Myth and Measurement: The New Economics of the Minimum Wage - Twentieth-Anniversary EditionFrom EverandMyth and Measurement: The New Economics of the Minimum Wage - Twentieth-Anniversary EditionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Transferable Skills, Job Matching, and The Inefficiency of The 'Natural' Rate of UnemploymentDocument15 pagesTransferable Skills, Job Matching, and The Inefficiency of The 'Natural' Rate of UnemploymentAbdur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Aggregation and Labor SupplyDocument44 pagesAggregation and Labor SupplyErlina RahmaNo ratings yet

- P. Diamond - Cyclical Unemployment, Structural UnemploymentDocument47 pagesP. Diamond - Cyclical Unemployment, Structural Unemploymentryurik88No ratings yet

- Hansen (1985)Document19 pagesHansen (1985)Marta Aurélia Dantas de LacerdaNo ratings yet

- Ejc 190Document18 pagesEjc 190Luis EscobarNo ratings yet

- Job Matching and Wage DistributionDocument29 pagesJob Matching and Wage Distribution杨诗琪No ratings yet

- Unemployment, Wage Bargaining and Capital-Labour SubstitutionDocument15 pagesUnemployment, Wage Bargaining and Capital-Labour SubstitutionHernanBuenosAiresNo ratings yet

- Solution Manual For Macroeconomics 10th Edition N Gregory MankiwDocument11 pagesSolution Manual For Macroeconomics 10th Edition N Gregory MankiwRalphLaneifrte100% (71)

- Hansen 1985 PDFDocument19 pagesHansen 1985 PDFadnanNo ratings yet

- Efficiency WagesDocument3 pagesEfficiency WagesKiên Thị LùnNo ratings yet

- FRBSF E L: Conomic EtterDocument4 pagesFRBSF E L: Conomic EtterZerohedgeNo ratings yet

- Credit Market Disequilibrium in Poland: Can We Find What We Expect? Non-Stationarity and The Short-Side RuleDocument27 pagesCredit Market Disequilibrium in Poland: Can We Find What We Expect? Non-Stationarity and The Short-Side RuleAude SeguedaNo ratings yet

- What Determines The Reservation Wage: Theory and Some New Evidence From German Micro DataDocument21 pagesWhat Determines The Reservation Wage: Theory and Some New Evidence From German Micro DataB2MSudarman IfolalaNo ratings yet

- Intermediate Macroeconomics (Ecn 2215) : Unemployment by Charles M. Banda Notes Extracted From MankiwDocument9 pagesIntermediate Macroeconomics (Ecn 2215) : Unemployment by Charles M. Banda Notes Extracted From MankiwYande ZuluNo ratings yet

- 6 Involuntary Unemployment : A. G. HinesDocument2 pages6 Involuntary Unemployment : A. G. HinesShabnam NazirNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument34 pagesUntitledBoton Immanuel NudewhenuNo ratings yet

- Has The U.S. Wage Phillips Curve Flattened? A Semi-Structural Exploration Jordi GalÌ Luca Gambetti December 2018Document33 pagesHas The U.S. Wage Phillips Curve Flattened? A Semi-Structural Exploration Jordi GalÌ Luca Gambetti December 2018Naresh SehdevNo ratings yet

- Unemployment and Business Cycles: WWW - Federalreserve.gov/pubs/ifdpDocument63 pagesUnemployment and Business Cycles: WWW - Federalreserve.gov/pubs/ifdpTBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- Serrano 2019 Mind The Gap TDDocument36 pagesSerrano 2019 Mind The Gap TDJhulio PrandoNo ratings yet

- Insider Outsider TheoryDocument21 pagesInsider Outsider TheorysukandeNo ratings yet

- JOHNSON (1978) - A Theory of Job ShoppingDocument18 pagesJOHNSON (1978) - A Theory of Job ShoppingSergio Alejandro Ropero SantiagoNo ratings yet

- Theories of WagesDocument14 pagesTheories of WagesGracy RengarajNo ratings yet

- 2011 25 PDFDocument26 pages2011 25 PDFMas RakaNo ratings yet

- Top 4 Models of Aggregate Supply of WagesDocument9 pagesTop 4 Models of Aggregate Supply of WagesSINTAYEHU MARYE TESHOMENo ratings yet

- Mccall Job SearchDocument15 pagesMccall Job SearchSubhrodip SenguptaNo ratings yet

- Inflation ExpectationsasaDocument29 pagesInflation ExpectationsasaAnonymous Di1zSIkRBHNo ratings yet

- New Classical MacroeconomicsDocument4 pagesNew Classical MacroeconomicsLuka KangoNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id920959Document42 pagesSSRN Id920959Katitja MoleleNo ratings yet

- Labor Demand Elasticities: SummaryDocument4 pagesLabor Demand Elasticities: SummaryOona NiallNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1-Introduction To EconometricsDocument16 pagesChapter 1-Introduction To EconometricsMuliana SamsiNo ratings yet

- Lect 7 The New Keynesian ModelDocument13 pagesLect 7 The New Keynesian ModelTeddyBear20No ratings yet

- 2013, Papp, RedDocument13 pages2013, Papp, RedErnesto MoraNo ratings yet

- Macro Economics Mankiwscarth6e - ch07 SolutionsDocument12 pagesMacro Economics Mankiwscarth6e - ch07 SolutionsZhichang ZhangNo ratings yet

- Dialnet UnemploymentInsuranceAndJobTurnoverInSpain 3630985 PDFDocument45 pagesDialnet UnemploymentInsuranceAndJobTurnoverInSpain 3630985 PDFManish BoygahNo ratings yet

- Immigration, Labor Market and Wage Inequality: Codrina Rada January 2002Document25 pagesImmigration, Labor Market and Wage Inequality: Codrina Rada January 2002sdsdfsdsNo ratings yet

- Schor, J. B. (1985) - Changes in The Cyclical Pattern of Real Wages Evidence From Nine Countries, 1955-80. The Economic Journal, 95, 452-468.Document18 pagesSchor, J. B. (1985) - Changes in The Cyclical Pattern of Real Wages Evidence From Nine Countries, 1955-80. The Economic Journal, 95, 452-468.lcr89No ratings yet

- Petrovsky, N. (2017) - Solving The Diamond-Mortensen-Pissarides Model AccuratelyDocument40 pagesPetrovsky, N. (2017) - Solving The Diamond-Mortensen-Pissarides Model AccuratelyDiego HuamanNo ratings yet

- Beyond Okun's Law Output GrowDocument24 pagesBeyond Okun's Law Output Growliupenzi06No ratings yet

- Wage Bargaining, The Value of Unemployment, and The Labor Share of IncomeDocument58 pagesWage Bargaining, The Value of Unemployment, and The Labor Share of IncomemondantesNo ratings yet

- Working Paper Series: The Shifting and Twisting Beveridge Curve: An Aggregate PerspectiveDocument37 pagesWorking Paper Series: The Shifting and Twisting Beveridge Curve: An Aggregate PerspectivecaitlynharveyNo ratings yet

- Working Papers: Declining Labor Turnover and TurbulenceDocument45 pagesWorking Papers: Declining Labor Turnover and TurbulenceTBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- REVIEW QUESTIONS Classical Economics and DepressionDocument5 pagesREVIEW QUESTIONS Classical Economics and Depressionkoorossadighi1No ratings yet

- Pellizzari 2004Document44 pagesPellizzari 2004Valentina CroitoruNo ratings yet

- NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2013: Volume 28From EverandNBER Macroeconomics Annual 2013: Volume 28Jonathan A. ParkerNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Unemployment and Inflation - Evidence From U.S. EconomyDocument6 pagesThe Relationship Between Unemployment and Inflation - Evidence From U.S. Economyabdur raufNo ratings yet

- Labor SupplyDocument24 pagesLabor Supplymanitomarriz.bipsuNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 - Wage Theories: Hrpe04 Handling Expatriate Workers in The PhilippinesDocument7 pagesChapter 6 - Wage Theories: Hrpe04 Handling Expatriate Workers in The PhilippinesPat TapNo ratings yet

- Shigeru Fujita and Giuseppe Moscarini 2017 American Economic ReviewDocument44 pagesShigeru Fujita and Giuseppe Moscarini 2017 American Economic ReviewHHHNo ratings yet

- APA GuidelinesDocument16 pagesAPA GuidelinesAadi RulexNo ratings yet

- Wiley The Scandinavian Journal of EconomicsDocument20 pagesWiley The Scandinavian Journal of EconomicsAadi RulexNo ratings yet

- 2010 FrantaDocument147 pages2010 FrantaAadi RulexNo ratings yet

- Wiley The Scandinavian Journal of EconomicsDocument23 pagesWiley The Scandinavian Journal of EconomicsAadi RulexNo ratings yet

- WRAP Oswald Aerfeb2000Document21 pagesWRAP Oswald Aerfeb2000Aadi RulexNo ratings yet

- An Empirical Analysis of The Relationship Between Unemployment and Inflation in Nigeria From 1977-2009Document20 pagesAn Empirical Analysis of The Relationship Between Unemployment and Inflation in Nigeria From 1977-2009Aadi RulexNo ratings yet

- 475 - 10 - PetrucciDocument13 pages475 - 10 - PetrucciAadi RulexNo ratings yet

- Michon Chebat 2007 EARCDDocument18 pagesMichon Chebat 2007 EARCDAadi RulexNo ratings yet

- Michon Chebat 2007 EARCDDocument18 pagesMichon Chebat 2007 EARCDAadi RulexNo ratings yet

- Michon Chebat 2007 EARCDDocument18 pagesMichon Chebat 2007 EARCDAadi RulexNo ratings yet

- Odour Music Service QualityDocument18 pagesOdour Music Service QualityAadi Rulex100% (1)

- From The CEO S Desk... : Equity Market Review and OutlookDocument6 pagesFrom The CEO S Desk... : Equity Market Review and OutlookAadi RulexNo ratings yet

- ITCD Assignment 1Document4 pagesITCD Assignment 1Sana SaraNo ratings yet

- Curriculum - Application (Solution) Consultant SAP SCM - SAP ERP - Order Fulfillment (Sales Order Management)Document3 pagesCurriculum - Application (Solution) Consultant SAP SCM - SAP ERP - Order Fulfillment (Sales Order Management)fiestamixNo ratings yet

- PROBLEM1Document25 pagesPROBLEM1Marvin MarianoNo ratings yet

- ISAGANI Vs ROYAL-position Paper 1Document5 pagesISAGANI Vs ROYAL-position Paper 1Gerald HernandezNo ratings yet

- Dokumen - Tips Meyers Pharmaceutical CompanyDocument7 pagesDokumen - Tips Meyers Pharmaceutical CompanySaktyHandarbeniNo ratings yet

- Common Stocks and Uncommon ProfitsDocument7 pagesCommon Stocks and Uncommon ProfitsPrasanna Bhattacharya100% (1)

- BritaniyaDocument10 pagesBritaniyaRamakrishnan RamNo ratings yet

- Formulation of Strategy For EbusinessDocument11 pagesFormulation of Strategy For Ebusinessarun.vasu8412100% (2)

- Conclusion PDFDocument5 pagesConclusion PDFSamatorEdu TeamNo ratings yet

- Acctstmt HDocument3 pagesAcctstmt Hmaakabhawan26No ratings yet

- SoW 9. 10, 11 Economics Normal Track (3 YEARS)Document36 pagesSoW 9. 10, 11 Economics Normal Track (3 YEARS)Yenny TigaNo ratings yet

- PSPM AA025 - ANSWERS CHAPTER 7 Absorption Costing and Marginal CostingDocument7 pagesPSPM AA025 - ANSWERS CHAPTER 7 Absorption Costing and Marginal CostingDanish AqashahNo ratings yet

- Wa0010.Document7 pagesWa0010.nitish.thukralNo ratings yet

- Demat Account Details of Unicon Investment SolutionDocument53 pagesDemat Account Details of Unicon Investment SolutionManjeet SinghNo ratings yet

- BIBM Written Math 2021-23Document11 pagesBIBM Written Math 2021-23simu991No ratings yet

- ACC16 - HO 1 - Corporate LiquidationDocument5 pagesACC16 - HO 1 - Corporate LiquidationAubrey DacirNo ratings yet

- Business Growth Strategy AnalysisDocument6 pagesBusiness Growth Strategy AnalysisGeraldine AguilarNo ratings yet

- Essay Test 2021 (Practice Test)Document3 pagesEssay Test 2021 (Practice Test)Philani HadebeNo ratings yet

- Labstan and TerminationDocument10 pagesLabstan and TerminationMichael Ang SauzaNo ratings yet

- Invoice - Amazon PDFDocument2 pagesInvoice - Amazon PDFRohan DesaiNo ratings yet

- VD Balanced Scorecard - Set of Templates For Building A Balanced Scorecard (Top Five)Document38 pagesVD Balanced Scorecard - Set of Templates For Building A Balanced Scorecard (Top Five)Quynh Anh Nguyen MaiNo ratings yet

- Objectives of NABARDDocument5 pagesObjectives of NABARDAbhinav Ashok ChandelNo ratings yet

- Example Safe Work Method StatementDocument2 pagesExample Safe Work Method StatementHamza NoumanNo ratings yet

- PMG 322 FinalDocument3 pagesPMG 322 Finalapi-673076565No ratings yet

- Activities Guide and Evaluation Rubric - Pre-TaskDocument4 pagesActivities Guide and Evaluation Rubric - Pre-TaskAlvaro LopezNo ratings yet

- Feasibility Study Final 1Document40 pagesFeasibility Study Final 1Andrea Atonducan100% (1)

- A Tale of Two Electronic Components DistributorsDocument2 pagesA Tale of Two Electronic Components DistributorsAqsa100% (1)

- Project Management, Tools, Process, Plans and Project Planning TipsDocument16 pagesProject Management, Tools, Process, Plans and Project Planning TipsChuma Khan100% (1)

- 914 1Document40 pages914 1Lovena RaichandNo ratings yet

- Definition of Lean: Systematic Identifying Eliminating Waste Flowing PullDocument7 pagesDefinition of Lean: Systematic Identifying Eliminating Waste Flowing PullKormanyos JoppeNo ratings yet