Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Winners and Losers of World Cup 2010

Uploaded by

api-197399248Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Winners and Losers of World Cup 2010

Uploaded by

api-197399248Copyright:

Available Formats

Winners and losers: The legacy of the 2010 World Cup

THE INDEPENDENT - THURSDAY 05 DECEMBER 2013

What will it all mean for South Africa when the circus has packed up and gone? Spain or Holland will lift the most coveted trophy in sport tonight, but it is the success or failure of only one nation that matters in the longer run. After months of toil, media inquisition, doubts and controversies, South Africa is about to discover whether hosting the world's biggest sporting event will pay off. South Africa, despite its national team going out in the first round, is already benefiting from a new sense of national pride and identity, as well as an economic boost from the thousands of travelling fans and 2.8bn of infrastructure projects. The big question now is whether it will all last. South Africa, once a global pariah as the home of apartheid, became a symbol of hope 15 years ago when it transformed peacefully into a democracy. Since then, it has been blighted by slow progress in tackling apartheid's legacy of crime and poverty. It has an unemployment rate of 24 per cent; half its population of 48.6 million are below the poverty line and life expectancy is just 49 years. It is hoped the economic boost of the World Cup will help to alter these figures. One thing that is for sure, however, is that, as with the Rugby World Cup in 1995, sport has helped bring a divided nation together. The Rainbow Nation may be a clich, but it seemed a pretty apt description of the atmosphere on the bus journey to Soccer City for the opening match of the World Cup. At the front sat Phume, a large black woman decked out in the yellow shirt of the South African team and a jester's hat in the red, green and blue of the national flag. Her young son was also wearing a yellow replica shirt. Behind her were four

white South Africans, flags painted on their cheeks and all wearing makarapas, the plastic mining helmets worn by the more hardcore football fan. The bus was a mix of white and black, all dressed in yellow. Phume started the chanting: "Give me a B!" she bellowed, and her fellow passengers 40 in all yelled back in unison. She spelled out "Bafana Bafana", the nickname of the South African team, and everyone sang along. South Africa played only three matches. But on every occasion fans gathered there was a mix of races and a genuine sense of national unity. Afrikaner rugby fans ventured to the fan park in Soweto to watch the Uruguay match on a big screen. Indian families that had never been interested in football took their children to the stadium in Bloemfontein for the France game. Robert Nyamane, 17, who leads tourists on a bicycle tour of the Orlando district, recalled his visit to a Soweto fan park. "When we are watching soccer on the big screen, all of us see one thing and all of us cheer. People see that South Africa has changed. It has made me proud," he said. The bill for hosting the World Cup is 2bn. Or maybe it's 2.5bn. No one can quite put a final figure on it. What everyone knows is that six years ago it was supposed to be 200m. The money has not just gone on stadiums. The Gautrain opened a few days before the World Cup started. Africa's first high-speed rail link is not without its critics. It is too expensive. It serves only the rich. There are more pressing transport needs. "The poorest people needed bus networks from the townships to work," said Josephine Osikena of the Foreign Policy Centre in London. "If that had happened people wouldn't have to get up at the crack of dawn just to get to work. High-speed rail services won't benefit the poorest." Road networks have been revamped and the telecommunications system has been transformed. Tens of thousands of jobs were created in the construction industry and this has helped existing businesses too. No one can put a price on the long-term benefit to South Africa. It is hoped that in five years' time unemployment will fall to 20 per cent, and life expectancy will be up to 50 years and only 47 per cent of people will be below the poverty line. But everyone knows who really benefits. Fifa, described in The New York Times as the "imposing overlords" of international football, expects to rake in about 2bn from the World Cup. It will pay tax in South Africa on none of it. Fifa made its money through corporate sponsorship, or "partnership" as it prefers to term it. Those partners needed protection, so Fifa insisted that phrases such as "World Cup" and even "2010" were not to be used by any other companies. One South African airline, Kulula.com, tried to get round the rules by declaring it was "the unofficial airline of you-know-what". Fifa insisted the ads were removed. Undeterred, Kulula.com put out adverts referring to "the thing that's happening right now". South African street hawkers who normally sell their horns and hats outside stadiums were moved to an exclusion zone placed around each venue.

"Fifa has made a lot of money out of this and it should be going to the disadvantaged... helping to create jobs, but it hasn't done as much of it as it could," said Haratio Motjuwadi, editor of the Soweto paper Sunday World. The Mzimhlophe hostel in Soweto was built in the 1950s for mineworkers. There are dead rats among the rubbish in the dirt streets outside, where children play and chickens peck. Inside one of the cramped dwellings sits Mxolisi, who shares the two rooms with his three brothers. There is no toilet or running water, but there is a colour TV and he sits transfixed by a replay of Carles Puyol's semi-final winner for Spain against Germany. It is a striking juxtaposition, yet this is a country long used to divides. On the streets of Soweto the prevailing mood appears almost wholly positive, at least from a scratch of the surface. The nearest thing to a dissenting voice comes from Mountain Msezane, at work in the nearby Klipsruit Fish and Chips store. He complains that "there is no knock-on effect" for his business and that the World Cup is "only for upmarket people". Yet his complaints come mixed with hope: more tourism, less crime, perhaps even "bigger things" for Soweto. The township has benefited from some of the new transport infrastructure, including the Rea Vaya bus system and upgrades to the Metro Rail system. In the weeks leading up to the tournament, Johannesburg was full of yellow diversion signs as roads were tarred. There was a deadline that had to be met. But there has been no such sense of urgency for South Africa's most pressing problems. The crime rate remains one of the highest in the world. Millions still live in slums. These things are a legacy of apartheid. It is often forgotten that in 1994 crime was far higher and the country was all but bankrupt. The World Cup organisers all of them South African have proved what the country is capable of. The challenge now is crime, education, housing, poverty. Women like Phume will do their best to make sure the pressure remains. As she got off the bus, she turned to one of the white fans in the makarapa. "See? See what we can really do when we try?" Steve Bloomfield is the author of 'Africa United: How Football Explains Africa'

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Cca FeedbackDocument12 pagesCca Feedbackapi-197399248No ratings yet

- Dcs Ccas 2014-15Document12 pagesDcs Ccas 2014-15api-197399248No ratings yet

- Water UsesDocument32 pagesWater Usesapi-197399248No ratings yet

- Year 7 Tourism AssessmentDocument7 pagesYear 7 Tourism Assessmentapi-197399248No ratings yet

- Introduction To SustainabilityDocument14 pagesIntroduction To Sustainabilityapi-197399248No ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

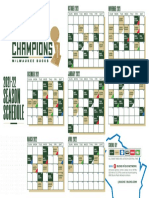

- 2021-22 Milwaukee Bucks ScheduleDocument1 page2021-22 Milwaukee Bucks ScheduleTMJ4 NewsNo ratings yet

- ENG - PRE AFF ManualDocument29 pagesENG - PRE AFF ManualdrGunjanNo ratings yet

- November 2018 Current Affairs Quick Review - Gr8AmbitionZDocument19 pagesNovember 2018 Current Affairs Quick Review - Gr8AmbitionZBansal ShikHarshNo ratings yet

- Chess Results ListDocument4 pagesChess Results Listreloco cheNo ratings yet

- Current Event ProjetDocument3 pagesCurrent Event ProjetSedrat KawaiahNo ratings yet

- Open Cloze ExercicesDocument14 pagesOpen Cloze ExercicesBrahlisNo ratings yet

- ĐỀ KT HK II - Tiếng Anh 3 Smart StartDocument7 pagesĐỀ KT HK II - Tiếng Anh 3 Smart StartAnhNo ratings yet

- No. 218 / D/Acad/2011. Date: 18-05-2011Document15 pagesNo. 218 / D/Acad/2011. Date: 18-05-2011balichakra_santoshNo ratings yet

- Hasami ShogiDocument3 pagesHasami ShogiJason TaylorNo ratings yet

- Plank Progression - Wk1-Wk4Document4 pagesPlank Progression - Wk1-Wk4jakeNo ratings yet

- Guidebook EnglishDocument2 pagesGuidebook EnglishĐào Duy TùngNo ratings yet

- Skateboard TrickswssDocument1 pageSkateboard TrickswssIulian PopaNo ratings yet

- Articles - Tokitsu-Ryu1Document38 pagesArticles - Tokitsu-Ryu1kyo4lifeNo ratings yet

- Patellar Tendinopathy in Team Sports Preventive.4Document11 pagesPatellar Tendinopathy in Team Sports Preventive.4Martiniano Vera EnriqueNo ratings yet

- 1 Bar ChartsDocument5 pages1 Bar ChartsSami AachaNo ratings yet

- Tae Kwon Do: Moo Duk KwanDocument46 pagesTae Kwon Do: Moo Duk Kwanbrendan lanzaNo ratings yet

- Rowing and The Same-Sum Problem - John BarrowDocument11 pagesRowing and The Same-Sum Problem - John BarrowAnonymous PmoR67iS2JNo ratings yet

- Literature Review: Commented (1) : This Was Definitely A Good SentenceDocument4 pagesLiterature Review: Commented (1) : This Was Definitely A Good SentenceazizalramdhanNo ratings yet

- TF 16401331Document15 pagesTF 16401331meryNo ratings yet

- From The Deck Up: Using Rig Analysis To Trace The Origins of The Scottish SgothDocument59 pagesFrom The Deck Up: Using Rig Analysis To Trace The Origins of The Scottish SgothArchy_sailorNo ratings yet

- Physical Education Team Sports (PETS) - Central Washington UniversityDocument4 pagesPhysical Education Team Sports (PETS) - Central Washington UniversityJOHNSON KORAINo ratings yet

- Africa Continent, Africa FactsDocument3 pagesAfrica Continent, Africa FactsEvery SportsNo ratings yet

- Brian McCartan PortfolioDocument16 pagesBrian McCartan PortfoliofuzzbrianNo ratings yet

- What Is A Warm Up and How To Warm Up ProperlyDocument5 pagesWhat Is A Warm Up and How To Warm Up ProperlyHamilton DurantNo ratings yet

- Therapeutic Exercise Movement AssignmentDocument4 pagesTherapeutic Exercise Movement Assignmentapi-272092949No ratings yet

- Hyundai Tucson 2010Document6 pagesHyundai Tucson 2010Jorge Antonio Guillen100% (1)

- ADVERBS OF FREQUENCY - Liveworksheets ID 1569824 - 102062020357062Document3 pagesADVERBS OF FREQUENCY - Liveworksheets ID 1569824 - 102062020357062Larisa M.No ratings yet

- Foseco India LTD.: Explain Business Model, Derive The Cost Sheet in Goldratt FormulaDocument23 pagesFoseco India LTD.: Explain Business Model, Derive The Cost Sheet in Goldratt FormulavikassahlotNo ratings yet

- Aero PhoneDocument3 pagesAero PhoneMargie Ballesteros ManzanoNo ratings yet

- Beginners Guide To ArcheryDocument7 pagesBeginners Guide To ArcheryHarry NurdianNo ratings yet