Professional Documents

Culture Documents

History of Windward Bananas

Uploaded by

BebeskbCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

History of Windward Bananas

Uploaded by

BebeskbCopyright:

Available Formats

History of Windward Bananas From Sugarcane to Bananas The Windward Islands are mainly of volcanic origin and formation,

giving rise to their very rugged terrain. With steep hillsides and deep, narrow valleys. Farming in that kind of environment has been very challenging. Therefore, the banana farms are not like those typically found in other banana-producing areas, with acres of flat land and deep topsoil. However, that has not daunted the hundreds of farmers who, since the early Fifties, have struggled diligently under challenging conditions to earn a living from cultivating bananas. Another characteristic of the banana farming in the Windwards Islands is reflected in the changes in land tenure systems and in farming over the years. Agriculture in these former British colonies has progressed from the dominance of the plantation or estate system using hired labour, initially to subsistence farming on the hillsides and then to smallholder production of cash crops, like bananas, and full integration into the export trading economy. Until the early Seventies, about 50% of the arable lands were still in the hands of about 1% of the farmers. Since then, successive Governments have embarked on extensive land reform programmes, resulting in the division of many of those estates into small holdings of average size of 2 hectares, and distribution to former estate workers. Since the middle to late Seventies, these smallholdings have contributed to the bulk of banana production in the Windward Islands. Agriculture in the Windward Islands has always been export oriented. Before bananas were introduced as an export crop, the islands exported mainly sugar. At various times, there were also other export crops such as cocoa, nutmeg, coconut (copra), arrowroot and citrus. However, except for cocoa and nutmeg, which have survived in Grenada, the others were largely unsuccessful and gradually declined in importance. Indeed, even sugar, the principal export for many years, suffered a major decline with the introduction of beet sugar production in Europe. Increasing supplies of sugar beet, and the competition it created, forced prices down and placed the sugar industries in the Caribbean under tremendous pressure. It was difficult for the Windwards sugar industries to compete internationally. Also, they had to compete with the rest of the Caribbean from Jamaica to British Guiana, all of which were major sugar producers. In the early Fifties, when the situation became extremely difficult, it was time to find a solution, if not to save the sugar industries but to protect the islands from economic collapse and avert social unrest. At the time, the islands were Crown Colonies and therefore the burden of responsibility lay mainly with the British Government. Agriculture was the main, if not the only, source of revenue for the islands. The rest came from the British Treasury. There were no other major industries such as

mining, manufacturing or tourism. The collapse of the sugar industry, unless it was replaced by a suitable alternative, would have been disastrous for the islands. Serious social unrest, like that which had occurred in the thirties and gave rise to a Royal Commission, would inevitably have had major consequences for HM Treasury resources. There was, at the time, no viable alternative to agriculture. What was required, therefore, was another export crop to replace sugar in magnitude and economic importance, which could employ the relatively large and growing rural population. Bananas fitted the bill perfectly. Not only was it relatively easy to shift to bananas on the larger cane fields, but also banana cultivation provided a much greater attraction to the growing number of small (then) peasant farmers. Cultivation practices could be easily adapted to small farm conditions. Indeed, the banana is the perfect cash crop for the small farmer. It is non-seasonal and, through the ratooning process, has a continuous cropping system, which provides a weekly or fortnightly harvest. This means that, for the self-employed small holder, it provides a regular source of income or cash flow throughout the year. As far as HM Government was concerned, apart from avoiding a further drain on its Treasury, the introduction of bananas as an export crop in the Windward Islands would bring one other major benefit. As Crown Colonies, the Windward Islands were in the Sterling currency area and so imports of bananas from the islands, rather than from the Dollar area of Latin America, would save Britain valuable foreign exchange, in the immediate post-war period. Indeed, there was a large and growing market for bananas in the United Kingdom. So with the active encouragement of the British Government, the Windward Islands readily abandoned unprofitable sugar cane production for bananas, in 1950. However, this had to be under special or protective arrangements, because of the physical constraints that militated against the ability of the Windward Islands to compete with the better-resourced Dollar Zone countries, where banana production and trade were dominated by the US multinational fruit companies. That essentially marked the birth of the banana industry in the Windward Islands and of the market protection that the Windward Islands banana industry enjoyed in the United Kingdom until 1993. Market Access and Competition For forty years prior to 1993, the banana producers of Windward Islands and Jamaica had enjoyed preferential access as traditional suppliers to the UK market. UK Government support for the traditional Caribbean suppliers, in the form of preferential market access arrangements, was maintained until July 1993, when the Common Market Organisation (CMO) for bananas was established in the European Community. Then, the preferential arrangements for African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) bananas were extended under a new import regime that encompassed the entire Community.

However, the new regime suffered a series of challenges in the World Trade Organisation (WTO), from the Latin American (Dollar Zone) countries, led by the United States. As a result, the regime underwent a number of changes, which saw a temporary settlement in 2001. As a condition of the 2001 settlement agreement, the EU banana import regime was again modified in 2006, when the arrangements were replaced by a flat rate tariff of 176 per tonne on bananas imported into the EU from the Dollar Zone countries. However, the ACP suppliers were granted exemption from that tariff up to a total annual volume of 775,000 tonnes. But total ACP supply far exceeded that duty-free quota, which was administered largely on a first-come, first-served basis. Under those arrangements, there were no quantitative restrictions on imports and so once the 176 per tonne duty was paid, any volume of bananas could have entered the market. Unfortunately, that did not end the dispute, as the level of the tariff became the subject of another complaint in the WTO. Those changes systematically weakened the market access arrangements for the Windward Islands and the other ACP banana suppliers and resulted in a steady erosion of the position of Windward Islands bananas in the UK market. Today, the market operates without any quantitative restrictions or quotas and while ACP bananas are exempt from import duty the tariff on bananas from the Dollar Zone countries has fallen to 132 per tonne. More so, it is scheduled to continuing falling every year down to 114 per tonne. Needless to say, this tariff offers little or no market access protection for the small holder banana farmers of Windward Islands. Therefore, the Windward Islands banana industry must rely increasingly on traditional consumer support to survive in the UK market. Naturally, with increasing competition and supply chasing demand, banana prices have come under severe pressure, particularly in the years since 2001. The retail price of loose bananas is now lower than it was 20 years ago and about 50% below the 2001 level, demonstrating the extent of price competition and deflation in the banana market to which the traditional suppliers have been subjected. This intense price competition has already dealt a devastating blow to the banana industry of the Windward Islands. Windwards banana exports to the UK have declined from 274,000 tonnes in 1992, or 45% share of the UK market, to 15,100 tonnes in 2012, or just 2% of the UK market. Notwithstanding the competitive pressures, the Windward Islands banana farmers who remain in the industry, with the support of Winfresh, are determined to survive and will do whatever it takes to meet the demands of the highly competitive market. One means of achieving this was by full conversion to Fairtrade. Only by selling their bananas as Fairtrade have the banana farmers of the Windward Islands been able to remain, or have any hope of remaining, in the market. However, even Fairtrade, with

all its good attributes and intentions, has not been able to shield the Windwards banana industry from the relentless competition and downward price spiral in the market place. Fairtrade, which once served the interests of small holders, has been opened to plantation or large scale farming and they are now dominating the market. In effect, Fairtrade bananas have been commoditised and the small holders, like those in the Windward Islands, are losing market share to large suppliers at an alarming rate. The Banana Industry Today The Windward Islands banana industry has undergone major changes over the years, both structurally and in the way the crop is grown, harvested, packed and presented to market. These changes have not been without some pain but they have been necessary to meet the requirements of a competitive and changing market. However, despite that, the industry remains one that is made up essentially of small farms, owned and operated by men and women who rely on it for their livelihood and who are committed to its future. In 1992, the Windward Islands banana industry consisted of about 27,000 farmers cultivating approximately 17,000 hectares, on farms that averaged less than 1 hectare. Today, with increased competition forcing many of those growers out of the industry, the numbers have dropped to less than 700 growers cultivating a total of about 1,500 hectares. The majority are full-time farmers whose families or households depend solely on income from the farms. Unlike plantation farming that benefits from large-scale investment in irrigation, mechanization and other farm infrastructure, the small farms of the Windward Islands are unable to generate the income flow to justify such investments. Therefore, they are not in a position to benefit from the kind of economies necessary to maintain cost of production at a competitive level. Despite the structural disadvantages and notwithstanding the diminishing preferential market access arrangements, the Windward Islands industry has not surrendered to the competition. The industry continues to seek ways to improve productivity and to meet the quality standards of the market. However, these have been extremely challenging and any gains have been negated or completely offset by rising costs and falling market prices fuelled by increased competition among retailers. This inevitably translates into lower prices and income to the farmers, creating a vicious circle where they are then unable to invest in their farms. Annual banana production in the Windward Islands prior to the introduction of the Common EU market, in 1993, was around 280,000 tonnes. At the end of 2012, following a recent series of devastating hurricanes and disease outbreaks, production had fallen to a mere 15,000 tonnes, or just 5.3% of what it was just before the CMO. Many British consumers choose bananas from the Windward Islands because they know the fruit is smaller and tastier and that it has been traditionally grown under

an ethical production system. This intrinsic value of the product is its main appeal, given that it is more expensive to produce than the bananas that are grown under the plantation system of production. Windward Island producers, against all odds, have striven hard to meet the increasingly stringent quality demands of the market. Under Windward conditions, the rainy season poses problems for farmers to maintain consistently high quality. However, on average, the quality of Windward Islands bananas compares favourably with that of bananas imported from other origins. Indeed, at their best, Windward Islands bananas are truly unmatched in terms of quality, both cosmetically and intrinsically (Note that reference to quality is usually to the external appearance of the fruit, i.e. the absence of marks or blemishes on the skin). Apart from the physical constraints of the islands, the Windward Islands banana industry is vulnerable to natural hazards, such as hurricanes and extensive bouts of dry weather. In 1979 and 1980, for example, Hurricanes David and Allen hit the industry consecutively. Since then, there was Hurricane Hugo in 1989, prolonged dry weather in 1991, and the triple hits of Hurricanes Iris, Louis and Marilyn in 1995. Then there was Hurricane Lili in 2002 as the industry was recovering from drought conditions in 2001, immediately followed by Hurricane Ivan in 2003. More recently, there was Tomas in 2010 which all but decimated the banana industry and, in the middle of the recovery in 2011, came the outbreak of Black Sigatoka disease. These natural disasters inflicted a heavy cost on the industry but, fortunately, the farmers have always mustered the resilience and courage to recover from them. However, this is becoming increasingly difficult with falling incomes and rising production costs. In 1995, the Windward Islands banana industry established a certification programme based on an internal code of practice aimed at ensuring good farming practices among its farmers, covering the handling of pesticides, product traceability, preservation of the environment, record keeping, etc. This was the first attempt at establishing a GAP standard for the banana industry. A formal and widely recognized GAP protocol was later established by the European Retailer Working Group, known as EUREP-GAP, which has been superseded by GLOBAL-GAP. The management of the banana industry in the Windward Islands has undergone a complete revolution over the years. From a position where there was no involvement of local management beyond the local loading ports in the islands, today the industry is fully integrated, with all aspects of the supply chain under control of Winfresh and local management. The old-style monopolistic statutory boards have been replaced by commercially oriented private service companies operating at the local level. There are no monopolies and both the farmers and the buying or handling companies, who trade with Winfresh, have complete freedom to trade as they wish. However, notwithstanding some of the accomplishments so far, there remain many challenges to be overcome and still much work ahead. The ultimate objective

remains the creation of a modern, commercially efficient, fully integrated and sustainable supply chain across the Windwards banana industry.

NOTES: The fixed price arrangements are expected to be extended in 2002 and beyond but will be based on volume contracts jointly with the local Banana Companies and growers. This is intended to encourage planned and more evenly distribution of production to allow for better product management and improvement in meeting customer requirements. Phase I of the new EU banana regime was implemented on 1 July 2001. Under phase II, which comes into effect on 1 January 2002, the ACP quota will be reduced from 850,000 tonnes to 750,000 tonnes. Windward Islands bananas will continue to enjoy preferential market access under that quota. The new regime expires in December 2005. It is widely expected that the replacement regime that will come into effect in 2006 will be based on tariff only, with no quotas or quantitative restrictions on bananas from any origin.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Tourism Development Questions Multiple ChoiceDocument35 pagesTourism Development Questions Multiple Choiceprasadkulkarnigit90% (20)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Social Studies WK 2 Lesson PlanDocument10 pagesSocial Studies WK 2 Lesson PlanKnoxann Barrett0% (1)

- A Nation of Women: An Early Feminist Speaks Out by Luisa CapetilloDocument179 pagesA Nation of Women: An Early Feminist Speaks Out by Luisa CapetilloArte Público Press100% (2)

- Carib Studies Past Papers AnswersDocument45 pagesCarib Studies Past Papers AnswersAnita Jaipaul0% (1)

- Calypso Notes PDFDocument4 pagesCalypso Notes PDFAlina Ruiz FoliniNo ratings yet

- THEME 7 US in The Caribbean Complete With ObjectivesDocument46 pagesTHEME 7 US in The Caribbean Complete With ObjectivesJacob seraphine100% (2)

- Waldorf Schools: Jack PetrashDocument17 pagesWaldorf Schools: Jack PetrashmarselyagNo ratings yet

- Immigration and National Identities in Latin AmericaDocument368 pagesImmigration and National Identities in Latin AmericaCamila OliveiraNo ratings yet

- University of Nebraska - LincolnDocument159 pagesUniversity of Nebraska - Lincolnflechtma1466No ratings yet

- Group 12 - The Wealth and The Poverty of NationsDocument4 pagesGroup 12 - The Wealth and The Poverty of NationsNhat MinhNo ratings yet

- MHRD UGC ePG Pathshala: African PoetryDocument11 pagesMHRD UGC ePG Pathshala: African PoetrymahiNo ratings yet

- Caribbean Cultural DevelopmentDocument4 pagesCaribbean Cultural DevelopmentJaiiNo ratings yet

- Immigrant Labour SchemesDocument43 pagesImmigrant Labour Schemesmausernameaintunique75% (4)

- The Benefits of Learning A Foreign LanguageDocument2 pagesThe Benefits of Learning A Foreign LanguageUnkown WetlordNo ratings yet

- Pre-History: Dugout Canoes Hispaniola Cuba Caicos Islands Great Inagua Island Long IslandDocument2 pagesPre-History: Dugout Canoes Hispaniola Cuba Caicos Islands Great Inagua Island Long IslandakosierikaNo ratings yet

- Cahfsa: Caribbean Agricultural Health & Food Safety AgencyDocument12 pagesCahfsa: Caribbean Agricultural Health & Food Safety AgencyMahesh J KathiriyaNo ratings yet

- The Plant Bugs, or Miridae (Hemiptera: Heteroptera) of CubaDocument213 pagesThe Plant Bugs, or Miridae (Hemiptera: Heteroptera) of Cubazmgs100% (3)

- Chapter 18 OutlineDocument5 pagesChapter 18 OutlineFerrari94% (16)

- 13th Annual International Charles Town Maroon Conference Programme - June 23 and 24, 2021Document7 pages13th Annual International Charles Town Maroon Conference Programme - June 23 and 24, 2021Maximilian ForteNo ratings yet

- Cultural Challenge 1 Spanish 2Document3 pagesCultural Challenge 1 Spanish 2Alex Angel PerezNo ratings yet

- Enslavement in TrinidadDocument3 pagesEnslavement in TrinidadSkilledWizardNo ratings yet

- The Indigenous Peoples and The EuropeansDocument23 pagesThe Indigenous Peoples and The EuropeansNakia Hylton100% (1)

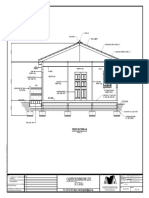

- Cadtech Designs Ltd. (C.T.D.L) : Cross Section A-ADocument2 pagesCadtech Designs Ltd. (C.T.D.L) : Cross Section A-Aceon sampsonNo ratings yet

- Communities in Contact PDFDocument514 pagesCommunities in Contact PDFTubal CaínNo ratings yet

- Caribbean Social StructureDocument4 pagesCaribbean Social StructurePricilla George67% (3)

- R.Gonsalves, "On The Caribbean Civilization and Its Political ProspectsDocument41 pagesR.Gonsalves, "On The Caribbean Civilization and Its Political ProspectsShaina SmallNo ratings yet

- A. BoomertDocument12 pagesA. BoomertMariusz KairskiNo ratings yet

- The U.S. 50 States - Map Quiz GameDocument1 pageThe U.S. 50 States - Map Quiz GameNyah PeynadONo ratings yet

- CSEC Geography June 2016 P1Document15 pagesCSEC Geography June 2016 P1Carlos GonsalvesNo ratings yet

- Caribbean Guide 2020Document56 pagesCaribbean Guide 2020Melita ArifiNo ratings yet