Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dane Rudhyar - The Relativity of Our Musical Conceptions

Uploaded by

22nd Century MusicCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dane Rudhyar - The Relativity of Our Musical Conceptions

Uploaded by

22nd Century MusicCopyright:

Available Formats

Dane Rudhyar

The theory of Relativity is sweeping the intellectual world of today. For centuries our thoughts and feelings have been molded by certain definite structures which have crystallized along certain lines, and the characteristic fluidity of early times has transmuted into a state of utter rigidity, so that they appear to us as mysterious and most sacred idols. That these idols are transitory in essence, that they belong to the perpetually unfolding sphere of the Becoming, that W made them as they are, and that they have no absolute e!istence, but the e!istence that W insufflated into them, all these points seem never to enter the field of our mental or intuitional consciousness. "et in musical a!ioms which tyrannically rule over uropean music lies an absoluteness, a certainty e#ual to the a!ioms of physical science, which have so utterly vanished before a closer and more daring investigation lately. There is no e!cuse for the perpetuation of such a!iomatic creeds now that the discovery of $riental civilization, art, science, which are so utterly different from ours, shows us that, if during these last centuries of uropean culture we have discovered $% Truth, there is the possibility of another Truth, differing not in #uantity but in #uality. &n other words, now that we 'now appro!imately how (in past civilizations comparable to ours in many respects, in some even decidedly superior) *umanity was thin'ing, feeling, creating along lines totally different from our present ones, it seems impossible for us to cling so frantically to our own conceptions, above all to believe still that they are eternal, indisputable, absolute, and in no manner susceptible of transformation. %evertheless, if some pioneers have already attempted with an ever+increasing success to brea' the old idols, their wor' has, at the most, touched only the outer layers of the musical structure. What has been revolutionized as yet is only the construction, the form, the se#uence of music. But the musical unit, the note, stands undefiled, untouched to a very great e!tent. ,omposers li'e $rnstein and ,owell have by the use of clusters of sounds imperiled its e!istence, and, to a certain measure, the futurists- attempt to create an enharmonic scale, or Busoni-s third+of+tone scale, have paved the way to the future revolution. yet these tentative efforts arc still very empirical in character and do not reach even the essence of the sub/ect, at least consciously. &n order really to grasp the idea & mean to convey in this brief article, one must first understand what is the inner essence of the concept upon which all western music is based0 the %ote. &f you as' some one what a note of music is, you will be loo'ed at as almost mad. if, furthermore you as'0 1,an you imagine music without notes21 your interlocutor will leave you, despairing of your mental balance. "et, these two #uestions0 1What intrinsically is a note21 and, 13re notes an essential element of 4usic21 are #uite legitimate, and, if properly understood and discussed, will raise most interesting points. First, what is a %ote, according to the current musical theories2 3 %ote is the unit of our musical universe, the cell of the body of music. 3ll musical creations, from a popular refrain to a symphony, are aggregations of notes 5 vertical aggregations, or chords. horizontal aggregations, or melodies. &f, on the other hand, you as' for a definition of music you may find something li'e this0 4usic is the art of combining sounds. *ere immediately

we come across what seems a duplication. First we spo'e of notes, then, of sounds. &s there then a difference between a note and a sound2 &ndeed there is a difference. 6ound is an element of the 7niverse. verything around us is sound, sound that oftentimes we do not hear because of the limitations of our ear, yet in some respect sound. $ur music, however, does not use all this infinitude of sounds. it is too rich, too chaotic for our musical sense. we are lost in the profusion of audible vibrations. We, therefore, have selected some specific sounds produced by some almost invariable instruments, and have thus created a little cosmos of sounds in which we feel at home. We have e!purgated %ature, we have encaged it, and thus re/oice in our easy mastery over this atrophied material. This material is what we call musical sounds. But a note is theoretically something different. A note is an abstract concept. &t has no sense+reality in itself. When we thin' of the note 3, we thin' of something which is a pure abstraction. First, we thin' of it, independently of the pitch. 3s' a bass, a tenor, a soprano to sing you an 3, and you will have 8 different sounds. yet you may say of each of them, 1&t is an 3.1 6econdly, suppose the pitch of the sound be given, we thin' of it independently of the #uality. For should a trumpet, a violin, an nglish horn, play the same 1a1, in reality we should have three sounds largely differing in quality and in power of rousing sub/ective emotions. &f we analyze the first case we come in contact immediately with the notion of what we call octave+sounds. &t is a very strange notion. We say that a is the octave-sound of 3. What does it mean2 6cientifically it means that if the fre#uency of 3 is e#ual to n, the fre#uency of a is e#ual to 9n. &t is simple enough, abstractly. "et why should we say that the vibration 9n is in some way the same as the vibration n, enough the same, at any rate, to give it the same name2 We could as well have said that 3 being the name given to the sound whose fre#uency is n, a would be the name given to the sound with a fre#uency of 8n. &n other words, why not have called an octave, the space comprehended between a certain sound and the sound whose fre#uency is three times greater, instead of the space comprehended between a certain sound and the sound whose fre#uency is twice greater2 From a philosophical point of view, the number 8 in nature plays a part as important as the number 9 does. The Trinity is the basis of every religious system. the triangle is the most universal symbol, and the most perfect figure in many respects. The ob/ection which will be presented immediately is this0 We know sensorially that an octave is the repetition of the same sound at a higher pitch. we feel it. &f you play a twelfth (the interval corresponding to the ratio above+suggested, :08) you 'now that it does not sound li'e an e!tended unison, as the octave does. But the ob/ection is a very illusory one, 3s well say0 13n octave is an octave because it is an octave.1 We have been trained for generations to consider the sound a1 as something possessing the same emotional #uality as the sound a-, the same #uality to such an e!tent as to apply to both the same denomination. "et, we cannot help but see that these two

sounds are different. They are not the same. There is absolutely no reason why we should thin' they are the same, why we should call them by the same name. It is a mere convention, which has absolutely no natural, no fundamental basis. which, therefore, may be modified at any moment without any theoretical inconvenience. &n fact, $riental music has never recognized octave+sounds. The concept of octave+ sounds in ;apan is not understood, by old musicians at any rate. Their conception of 1scale1 differs so widely from ours that there is practically no such thing as 1scales1 in the $rient. They have modes, thousands of them. but that is very different. The difference is that, if you go deep into the esoteric conception of 4usic in the ast, you discover that the $riental music ignores the 1note1 as such. They ma'e music in terms of absolute pitch, not in terms of relative pitch. Their music is built upon modes wherein each tone, each 1compound sound1 has an individuality, an e!istence proper. $ccidental music, on the contrary, is built on the abstract concept of 1interval.1 3 scale is a progression of ratios, is a pattern made to order, which may be fi!ed at will at any pitch. &t is a sliding ladder, whose rounds are notes. between these rounds there is an absolute void, practically. 6o that outside these few rounds there is no music. there is only 1wrong notes.1 We do not thin' musically in term of sound, we thin' in terms of notes, or in terms of intervals, which is the same. for a note is the edge of an interval, as far as our musical theory goes, therefore a purely abstract factor. We are still under the influence of the Flemish school of counterpoint of the :<th 5 :=th centuries, with its algebraic formulae, its reversing parts and intricate puzzles. we are still, in theory, /uggling with intellectual puppets, artificial entities which we call 1notes1 and manipulate li'e wooden cubes, in order to build our musical castles. But these cubes arc corpses. they contain no life. We can pile them up, dispose them in beautiful decorative figures. but, do we get music2 Decidedly not. We attain to a sort of Decorative 3rt, a sort of moving architecture. but that is not music, real, absolute 4usic. %or is it real architecture0 you cannot apprehend it at once. it lies in between, a hybrid combination of elements half+intellectual, half+emotional. What & attac' here is not the principles of 4usical ,omposition. & should be foolish indeed to say that there should not enter any intellectual or abstract elements in the composition of a musical organism, as for instance a symphony. What & want to convey is the idea of the unreality, the un+musicality of that which is the unit, the cell, of all musical organisms in the West, viz. the %ote. &f again we come bac' to the $riental conception, we see that the formative units of a mode are living entities. The interval, the ratio of fre#uencies, do not count as basic elements. They came in music during the decadences when it became necessary to have strict regulations in order to chec' the decomposition of the sacred institutions and colleges. The primordial sounds used as bases were conventionalized natural sounds. We see in the early ,hinese annals how these primordial sounds were ta'en from the singing of a certain bird, from the bellowing of a cow, and so forth. Then, in order to attain a more fundamental characterization and to reach the plane of the archetypal sounds, as it were, of the natural voices, they were stabilized, the length of the sound+producing pipes precisely fi!ed. But

even when stabilized they 'ept all their initial fle!ibility. between each successive tone there was no void, but an insensible progression. each tone was a center influence, not a rigid tower of ivory. therefore they remained 1alive.1 ach musical sound, each tone, lived as an entity in itself. Transposition was un'nown as a principle of composition, because as soon as you begin to transpose you ta'e each sound as an abstract symbol, and no more as a living reality. &f you ta'e a cat and raise its atomic vibrations, by some mysterious process, it is no more the same cat, and probably no more a living being. &f you ta'e a sound and raise its pitch, it is no more the same sound. &n other words, wherever absolute pitch (theoretically) is not re#uired, music is no longer based upon tone (or life), but upon abstractions, upon intervals. &f musicians would 'now what a Mantram means in the ast, they would understand. They would understand that, in real 4usic, a tone, or compound+sound, and still more a series of tones, or modulations of sounds, or melody, are living organisms reacting directly upon other living organisms, visible or invisible. they would understand that the essence of music is magic (as ,ombarieu points out so clearly in his 1*istoire de la 4usi#ue1), that real music has a tremendous magical power susceptible of destroying and creating matter. &t is already a fairly common laboratory e!periment to blow out a big flame simply by sounding the proper tone to which the flame responds. in the same way a student in 4enlo >ar', ,alifornia succeeded in sha'ing the walls of his study when producing the proper tone to which they responded. (3re we not near the famous incident of the trumpets of ;ericho2) 3ll this means that a tone is an 1entity,1 and not an abstraction. that in 1abstractizing1 tones, or creating the concept of %ote, the vital, magical value of 4usic is 'illed. The note a1 given by a violin, and the same note given by a horn, are in fact two different sounds. We are used to consider them theoretically as identical, but they are not. their pathos is entirely distinct, their creative or destructive powers over matter are totally different. &n identifying them we overloo' what is really essential in them0 ?ife. We do li'e the scientist who 'ills first in order to dissect. %o wonder if he cannot discover the secret of ?ife@ %o wonder if 4usic has lost its olden power, in spite of the perfecting of instruments, and their multiplication. To tolerate this continual adaptation of a music written for one instrument to another instrument, proves the terrible primitiveness of our musical sense. although, evidently, in our system as it is, it does not really matter much. ?et us understand and face the truth. We $ccidentals, in spite of all our glorious musical repertoires, of our wondrous orchestras, have not yet learned what a sound is. ven in the analytic process of our art we are still in a period of relative infancy. We have been so drun' with our chords, our counterpoint, etc., that we have forgotten to care about the basis of all0 a comple! sound. "et what is harmony, if not the science of ma'ing comple! sounds2 We spea' of the note a1. But such thing does not e!ist e!cept in scientific e!periments. The a1 produced by a violin is only fictitiously called a1, because what a violin produces is, in fact, a compound-tone, that is, a prime and a certain amount of upper and lower partials,

specially upper ones, though the lower have been lately discovered in almost every sound we use in music. We practically never deal with pure sounds devoid of partials. We deal only with compound+tones. ach compound+tone has an individuality of its own. What is the difference between a chord and a compound+tone2 There is no #ualitative difference, only a #uantitative one. 3 single violin tone is a compound+tone of the first order. 3 chord emitted by a string #uartet is a compound+tone of the second order. They differ in degree of diversity, but only in degree. &f we courageously face these facts we reach immediately the following stri'ing conclusions0 !" There is no fundamental difference between 4onody and >olyphony. #" $ur modern *armony is but a part of an infinitely more comple! science (or art), of which $rchestration is also a part. $" $ur invention (@) of >olyphony is but a step leading to a more e!act synthesis of tones, wherein primes and partials will both be considered and strictly defined. %" $ur musical notation is a most inaccurate one, in so far as it leaves aside all partials. &f every musical sound is a compound+tone, a melody is not one unrolling thread of sounds, but several threads of sounds. it is, in fact, appro!imately the same thing as a succession of chords. The primes play merely the part of the bass of the harmonic succession. What we do then, when we note a melody by writing only the succession of its primes, is e!actly what composers of the :Ath century did, when, instead of writing the whole chords, they merely wrote the fundamentals. But most of the time they added to these fundamentals the numerical symbols of the chords. When we write a melody we are not even so accurate, relatively. &n other words, melody is never to be found in music. very melody is a hidden harmonic succession, and should be treated as such. &n fact, it was treated empirically as such by $riental 4usic. for a given mode or melody was to be played only by one type of instrument, as a rough indication, not only of the given primes, but also of the partials. Western music, having increased the number of instrumental categories, and forgotten the secret value of modes and their proper use according to time, season, hour, place, influences, has mi!ed up most distressingly the musical values. &ts notation, seemingly more accurate and precise, is in fact inferior in such respects to the $riental notation. What we call *armony is the art of combining musical sounds in vertical progression. We are only beginning to 'now what it means. 7ntil now we have dealt only with notes, with combinations of abstract relations of intervals. But in the future we shall deal with compound+sounds understood in their integrality (primes and partials). Thus the #uality of sounds will be studied, as well as the pitch of the principal tone, or prime. Thus the science of $rchestration will become a part of *armony. but a science of $rchestration so conceived

as to differ materially from the one we have today. Today we mi! instruments absolutely empirically, instinctively. The science of partials being actually non+e!istent, we have no means of 'nowing scientifically what we are doing. Furthermore, the comple!ity of our modern orchestras is not only, materially and financially, nonsensical, but musically produces lu!urious effects which most of the time 'ill the real depth of musical e!pression, although it is a great help to composers who have nothing to e!press. The orchestra is an instrument of decadence. &t is all on the surface. it is, li'e the modern palaces all gold, all light, all glitter. but in such a profusion of ornaments no soul can dwell. $ur orchestral music is absolutely un+spiritual, in the real sense of the word spiritual. &t has no simplicity, no spontaneity, no purity. &t is either the result of a poverty of spirit trying to conceal its heavy layers of tinsel, or the frantic attempt of an imprisoned soul to brea' the inertia of notes and create music based almost e!clusively upon half+revealed partials. What 4usic needs is, above all, a 'ind of electric instrument, conceived in a way similar to the basic idea of the 1Telharmonium1 of Dr. ,ahill e!perimented with some :< years ago. 6uch an instrument will permit us to produce by combination any sound, whatsoever 5 and therewith arrive at the third and fourth propositions enumerated above. Thus we shall rid ourselves of the empirical division of sounds into primes and partials, at least for practical purposes. &nstead, we shall have compound+tones, with not only the relative intensity of partials and primes as a #uantity accurately defined, but also with the numbers and disposition of partials as a precise musical factor. 3s an e!ample let us ta'e a melody, a- b- e- d- g-. &n our present musical system a- b- erepresent different notes sufficiently defined by their name. &n the future a- will give place to a compound+tone composed, let us say, as follows0 prime& aupper partials& :. 9. 8. <. A. B. lower partials& :. 8. C. But that is not all. The intensity of the prime being ta'en for instance as :DD, the intensity of every partial would be given proportionally. Thus every compound+tone will be determined in all its components. 3 progression of such compound+tones would be what we call a melody. *aving enriched with unheard+of tones the monodic line, the ne!t natural step will be to constitute a polyphony in the spirit of >alestrinian polyphony. But instead of the simple and restricted #uality of the human voice, we shall have the wondrous splendor of an infinitude of cosmic sounds. For with such an instrument as we imagine, every #uality of sound is theoretically possible. 3 dazzling profusion of new materials will flood the imagination of the future creators. and yet an utmost purity and simplicity may be attained, because all this splendor will transfigure the quality of the tone, not, the quantity of it. What we shall gain, is an almost incredible subtlety, an ever+changing chatoyment of colors, not so much of outer colors as now, but of innermost nuances. The new wealth will

be within, not without, it will not be a mi!ture, but a selection out of an infinitude of potentialities. %ot only upper partials will be used, but lower partials, as they have been detected recently in such abundance in the tone of bells. &n fact, the prime sound 5 the only one we consider now 5 will appear then as a radiating center of dynamic tonal energy, as a 6un surrounded by the double series of planets, the over+ and under+tones. ach compound+ tone, therefore, will be a microcosm, living of its own life, e!panding a certain vital energy, acting powerfully over all cosmic organisms. 3 melody then will be, by comparison, a chain of solar systems 5 a polyphonic whole, a 7niverse. Then indeed 4an will be worthy of the name of ,reator@ The #uestion of notation is very simple. the best way to arrive at an easy reading is to have the music printed upon a roller, similar to the ones used in pianolas, but unrolling horizontally instead of vertically, as has already been suggested by some inventor. The diagram printed on the opposite page will give a very incomplete yet basic idea of the possibility of such a notation.

&n fact, it is merely an adaptation to the new mechanical potentialities of the old ;apanese notation of ,hinese origin. This ;apanese notation, which one may find reproduced in some boo's upon ;apanese music, is also vertical and horizontal, and uses curves or straight lines in almost the same way as & do here. But the #uality of the tones (i.e., the overtones) is not mentioned, although #uantity of letters, symbols, etc., give detailed indications concerning instruments, nuances, etc.

The notation by curves or lines (instead of by points or notes) is very much more supple and leaves to the e!ecutant a part 5 small but necessary 5 for personal feelings. &t has the great advantage of giving the impression of a continuity, therefore of ?ife (6ee Bergson, 1,reative volution1) whereas our notes give the feeling of division, of restlessness, of individualism. & repeat again here that music has nothing to do with individualism. it is above all a cosmic e!pression. &t is the cosmic e!pression of 4an-s consciousness. The time+values are given as in mathematical curves by the horizontal elongations of any fragment of the curve. $nce the essential features of the diagram are understood, one can easily imagine a score (roller) containing three or four curves. We shall then get on a larger scale something e#uivalent to the score of a mass by >alestrina, for three or four voices. &f one ob/ected that such a conception of simple polyphonic music limits the field of musical e!pression, & should answer that >erfection is concentration and selection. The music of a Eittoria is perfect because it comprehends no e'ternal elements. the music of Wagner is imperfect because it contains non-musical, e!ternal elements. Descriptive music is not music at all. >sychological music, so called, is e#ually futile as music. What the future will bring us is a synthesis of all arts. but within this synthesis, each component has to stay in its own place, to use its own means of e!pression, and not to ma'e a horrible mi!ture of the 1precedes1 of all combined arts. We want $rder, not ,haos. The music of today is chaotic, because it does not 'now what it wants. or even if it 'nows it does not dare to do the necessary thing to get there. &t is built upon anti+musical elements. it tries to destroy them, and does not 'now how. it feels that something is wrong, but does not 'now what. But above all, it has no ideal to e!press, no faith 5 social, religious, or any other 5 to support it. it is metaphysically aimless. That is the worst thing that can happen to an art. Wagner was great because he had a metaphysical conception, and knew it. 6o was 6criabin. 6travins'y is great today because he feels something immense without seeming to be able to e!press it consciously. wherefore we miss something in his music, however marvelous it is from a sensorial point of view. *e is, with a few others, the mirror of the humanity of to+day, striving in a half+dar'ness, rent at times by fulgurating lightning. But all are afraid of 1/umping beyond their shadows,1 as %ietzsche would say, afraid of clamoring for what 4usic needs, for what *umanity, 6cience, 3rt, Religion need a new basis, a new soul, a new faith. These pages do not pretend to be more than a s'etch of future possibilities, or necessities, as & believe. 4y endeavor was merely to open the eyes of musical thin'ers, to show that everything is unstable and relative in our music, and why it will be imperative to ma'e radical changes. This does not mean a revolution into nothingness, or a floundering about in the 7n'nown. $riental music is there, if properly understood, to tell us its secret, and to illumine our dar'ness. & am not advocating a going bac' to $riental music. That would be the greatest nonsense. We go forward, not bac'ward. But, as in ?ogic

antithesis succeeds thesis, and synthesis succeeds antithesis, & firmly believe that $riental music was the thesis, $ccidental music the antithesis, and that the future must give life to a synthesis in the direction here s'etched.

!( & might add here that the 1trinitarian octave,1 or the Twelfth ta'en as the basis for scales, has been, in fact, used during the early ,hristian centuries. We hear of the 1organum1 or singing fifths. & fancy these fifths were really twelfths. the twelfth appeared then as a consonance, as consonant as our octave (*elmholtz reaches the same conclusion). The progression of chords of ninths, dear to Debussy, is based upon the same duodecuplc system. Twelve is furthermore the basis of the 7niverse, in all cosmologies. 6o the whole idea of the 1trinitarian octave1 is very much less fantastic than it appears at first. We have seen thus how, from the point of view of pitch, the conception of octave+ sounds is a mere artificial abstraction. from the point of view of the #uality of sounds we find that our current musical conceptions are e#ually un+natural.

You might also like

- Gerald Eskelin - Components of Vocal Blend Plus Expressive TuningDocument81 pagesGerald Eskelin - Components of Vocal Blend Plus Expressive Tuning22nd Century Music100% (2)

- Bruno Nettl - Infant Musical Development and Primitive MusicDocument6 pagesBruno Nettl - Infant Musical Development and Primitive Music22nd Century MusicNo ratings yet

- Gerald Eskelin - Lies My Music Teacher Told Me (Second Edition)Document175 pagesGerald Eskelin - Lies My Music Teacher Told Me (Second Edition)22nd Century Music86% (22)

- The Healing Power of MusicDocument10 pagesThe Healing Power of Music22nd Century Music100% (2)

- Alexander J. Ellis - On The Musical Scales of Various Nations (Journal of The Society of Arts For March 27, 1885, Vol. Xxxiii)Document48 pagesAlexander J. Ellis - On The Musical Scales of Various Nations (Journal of The Society of Arts For March 27, 1885, Vol. Xxxiii)22nd Century Music100% (5)

- Mauricio Castillo and Suresh K. Mukherji - Practical Embryology of The Temporal BonesDocument4 pagesMauricio Castillo and Suresh K. Mukherji - Practical Embryology of The Temporal Bones22nd Century MusicNo ratings yet

- Kathleen Schlesinger - The Greek Aulos (1939, 1970)Document679 pagesKathleen Schlesinger - The Greek Aulos (1939, 1970)22nd Century Music100% (5)

- Tibetan Singing Bowls - Denis Terwagne and John W.M. BushDocument22 pagesTibetan Singing Bowls - Denis Terwagne and John W.M. Bush22nd Century Music100% (1)

- Shakuhaki Design: Excellent Guide To FlutesDocument281 pagesShakuhaki Design: Excellent Guide To Flutes22nd Century Music100% (11)

- Revive Verdi's Tuning To Bring Back Great Music (EIR Feature Article)Document21 pagesRevive Verdi's Tuning To Bring Back Great Music (EIR Feature Article)22nd Century MusicNo ratings yet

- Rex Weyler and Bill Gannon - The Story of HarmonyDocument168 pagesRex Weyler and Bill Gannon - The Story of Harmony22nd Century Music91% (11)

- Roger N. Shepard - Geometrical Approximations To The Structure of Musical Pitch (Article) (1982)Document29 pagesRoger N. Shepard - Geometrical Approximations To The Structure of Musical Pitch (Article) (1982)22nd Century Music100% (2)

- Alfredo Capurso - A New Model of Interpretation of Some Acoustic Phenomena. Circular Harmonic System - C.HA.S.Document26 pagesAlfredo Capurso - A New Model of Interpretation of Some Acoustic Phenomena. Circular Harmonic System - C.HA.S.22nd Century Music100% (1)

- Alfredo Capurso - The Circular Harmonic Temperament System - C.HA.S. ®Document13 pagesAlfredo Capurso - The Circular Harmonic Temperament System - C.HA.S. ®22nd Century MusicNo ratings yet

- Handbook of Acoustics For The Use of Musical Students (8th Ed) - Thomas Frederick HarrisDocument352 pagesHandbook of Acoustics For The Use of Musical Students (8th Ed) - Thomas Frederick Harris22nd Century Music100% (2)

- New Musical TuningDocument29 pagesNew Musical TuningMellyBelly52No ratings yet

- Opticks - Sir Isaac Newton (1952 Republication of The 1730 4th Ed.)Document536 pagesOpticks - Sir Isaac Newton (1952 Republication of The 1730 4th Ed.)22nd Century Music100% (3)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Period of Rotation of SunDocument17 pagesPeriod of Rotation of Sunbagus wicaksonoNo ratings yet

- Desmet Basis of Emotion On ProductsDocument7 pagesDesmet Basis of Emotion On ProductsMiguel Antonio Barretto GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Unistellar Fact SheetDocument3 pagesUnistellar Fact SheetLudovicUnistellar100% (1)

- Vikriti Year 2010 - 2011: by Chakrapani Ullal, USADocument14 pagesVikriti Year 2010 - 2011: by Chakrapani Ullal, USAfs420No ratings yet

- Yoga 6Document3 pagesYoga 6anantNo ratings yet

- Notes On Clifford Algebra and Spin (N) Representations PDFDocument14 pagesNotes On Clifford Algebra and Spin (N) Representations PDFAllan GonçalvesNo ratings yet

- Phy Aipmt 2015 QuesDocument6 pagesPhy Aipmt 2015 QuesakalikarNo ratings yet

- MIR - Smliga v. - in The Search of Beauty - 1970Document176 pagesMIR - Smliga v. - in The Search of Beauty - 1970avast2008100% (5)

- AlchemyDocument16 pagesAlchemyz987456321No ratings yet

- Advance BNN SyllabusDocument7 pagesAdvance BNN Syllabusduck taleNo ratings yet

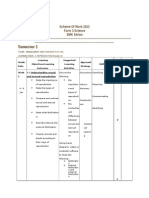

- Scheme of Work Form 3Document44 pagesScheme of Work Form 3Mona MohtarNo ratings yet

- A Lutheran Astrologer. Johannes KeplerDocument84 pagesA Lutheran Astrologer. Johannes KeplerCarlos OrsiNo ratings yet

- Aerial Robotics Lecture 2C - 4 Quadrotor Equations of MotionDocument4 pagesAerial Robotics Lecture 2C - 4 Quadrotor Equations of MotionIain McCullochNo ratings yet

- Laghu JatakamDocument195 pagesLaghu JatakamNarayana SabhahitNo ratings yet

- Theories On The Origin of The Universe and The Solar System: Prepared By: Mrs. Nina M. MoletaDocument20 pagesTheories On The Origin of The Universe and The Solar System: Prepared By: Mrs. Nina M. MoletaShiroko TenseiNo ratings yet

- DLP 2. Origin of The Solar SystemDocument3 pagesDLP 2. Origin of The Solar SystemManilyn Mugatar MayangNo ratings yet

- Keys of XibalbaDocument3 pagesKeys of XibalbaJonathan Robert Kraus (OutofMudProductions)No ratings yet

- Experiment 1Document3 pagesExperiment 1ChristineNo ratings yet

- Astrology of SexDocument120 pagesAstrology of Sexkrastroman89% (9)

- Entangled Representation of Heaven - A Chinese Divination Text From A Tenth-Century Dunhuang Fragment PDFDocument19 pagesEntangled Representation of Heaven - A Chinese Divination Text From A Tenth-Century Dunhuang Fragment PDFLukeNo ratings yet

- Katelyn Mejia - CRQ RenaissanceDocument7 pagesKatelyn Mejia - CRQ RenaissanceKatelyn MejiaNo ratings yet

- Exaltation Debilitation of Planets As Pe - V.P.jainDocument6 pagesExaltation Debilitation of Planets As Pe - V.P.jainwileraNo ratings yet

- You Said It's Called Supreme Mathematics RightDocument2 pagesYou Said It's Called Supreme Mathematics RightAuMatu89% (9)

- Navatara Chakra BasicsDocument2 pagesNavatara Chakra Basicsvksk195150% (2)

- OPRT Feb 27,2017: ChatDocument65 pagesOPRT Feb 27,2017: ChatbreakingthesilenceNo ratings yet

- Conv in Astrology - Venus in Aries ManDocument3 pagesConv in Astrology - Venus in Aries ManAyo RayNo ratings yet

- The Hydrogen 21-cm Line and Its Applications To Radio AstrophysicsDocument7 pagesThe Hydrogen 21-cm Line and Its Applications To Radio AstrophysicsKush BhatiaNo ratings yet

- Drawing - Sideral Zodiac and Galactic CenterDocument2 pagesDrawing - Sideral Zodiac and Galactic CenterBoris ZaslichkoNo ratings yet

- Sumalinog Teodoro Jr. LPDocument5 pagesSumalinog Teodoro Jr. LPDAITO CHRISTIAN DHARELNo ratings yet

- SAT II Physics Practice Test 2Document7 pagesSAT II Physics Practice Test 2td2012No ratings yet