Professional Documents

Culture Documents

THPW hHYH THPWHT

Uploaded by

lavvvenderOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

THPW hHYH THPWHT

Uploaded by

lavvvenderCopyright:

Available Formats

Who Is Happiest At Work?

Probably Not Who You Think By Brad Tuttle @bradrtuttle April 25, 20138, Time Magazine How to find happiness in the workplace? One theory has it that the most deeply fulfilled workers are those facing the most daunting challenges. Another holds that the formula for contentment is being surrounded by colleagues that pick up your slack. For insights regarding happiness and performance in the workplace, lets check out some recent research. Who Is Happiest at Work? Writing at Harvard Business Review, Rosabeth Moss Kanter, a professor at the business school and the author of Evolve! Succeeding in the Digital Culture of Tomorrow, says that the happiest people tend to be those facing the toughest but most worthwhilechallenges. Were talking stuff like teaching kids in inner city schools, working for solutions to homelessness, or improving health in developing countries. In her research concerning what motivates people at highly innovative companies, Kanter found, Money acted as a scorecard, but it did not get people up-and-at em for the daily work, nor did it help people go home every day with a feeling of fulfillment. On the other hand, when workers feel like they can make a difference, it leaves them more fulfilled. Thats a deeper level of happiness that money just cant buy. A study by Leadership IQ offers a very different perspective on what makes workers happy. The study found that in 42% of companies, the lowestperforming employees were more engaged and motivated than their middle- and high-performing colleagues. And why did the slackers enjoy their jobs more? A Fast Company post theorized: In most organizations, low performers are pretty much left alone. They are happy as clams because no one notices or bothers them. They can just sit there quietly and wont be discovered as long as no one does anything to alter the terrain. As for their higher-performing colleagues, no wonder theyre not quite as happy: They have to pull more weight to make up for the low performers. Many of the best workers are stressed out and feel undervaluedoften because, in fact, they are. Which Workers Perform Best on the Job? Extroverts are often considered to be good workers. Theyre likeable, chatty types, who come across as go-getters with charismatic leadership skills. Yet a new study published in the April issue of the Academy of Management Journal cites research indicating that extroverts also tend to be poor listeners, and not particularly receptive to input from others. (MORE: How the Best Tech Companies Treat Their Employees)

In a series of experiments, Corinne Bendersky, an associate professor at UCLAs Anderson School of Management, and Neha Parikh Shah, a professor at Rutgers Business School, studied how extroverts and neurotics worked in various team projects. The extroverts didnt fare well, according to evaluations by team members. A Forbes post quoted some conclusions made by Bendersky concerning how extroverts perform in team work environments: The extroverts are probably going to contribute less to the team and the contributions they make will be undervalued by the team, she says. They will do less and what they do will be under-appreciated. Theyll also talk too much and fail to take to heart the thoughts, insights, and suggestions of colleagues. Neurotics, on the other hand, were superstars who perform better over time at their jobs, as Bendersky told CNN: Our intuition about anxious, neurotic employees and colleagues is that their volatility and negativity is going to make them a drag on the team, said Bendersky. What we dont appreciate is that an aspect of that neurotic personality is really an anxiety of not wanting to disappoint our peers and our colleagues. Neurotics can actually be motivated to work really hard especially in collaborative situations. (MORE: Memo Read Round the World: Yahoo Says No to Working from Home) Neurotics also benefit because colleagues have lower expectations of them. More is expected of the talkative extroverts out there, so they have more to live up to. Extraverts contributions disappoint their peers due to the critical evaluations of the extraverts contributions rather than the high level of the initial expectations, the study states. This suggests that peers may infer that extraverts are motivated by self interests and interpret their contributions skeptically. Marissa Mayers highly publicized decision at Yahoo to force workers to come into the office (no more telecommuting) raised another question regarding what kinds of employees perform their jobs best. Speed and quality are often sacrificed when we work from home, stated the memo announcing Yahoos change in work policy. To become the absolute best place to work, communication and collaboration will be important, so we need to be working side-by-side. That is why it is critical that we are all present in our offices. Some of the best decisions and insights come from hallway and cafeteria discussions, meeting new people, and impromptu team meetings. Fair enough. But Kellogg School of Managements Leigh Thompson writes that in addition to creating spaces (physical or virtual) for workers to collaborate and bounce ideas off each other, what she calls caves are necessary as well. By a cave, she means a quiet, private spotperhaps a home office, but not necessarilywhere an employee can truly get down to business without the interruptions of chatty extrovert colleagues. You know, the kind of place that a neurotic might actually feel sorta comfortable

How Economic Inequality Is (Literally) Making Us Sick By Maia Szalavitz @maiaszOct. 19, Imagine there was one changeable factor that affected virtually every measure of a countrys health including life expectancy, crime rates, addiction, obesity, infant mortality, stroke, academic achievement, happiness and even overall prosperity. Indeed, this factor actually exists. I ts called economic inequality. A growing body of research suggests that such inequality more so than income or absolute wealth alone has a profound influence on a populations health, in every socioeconomic group from rich to middle class to poor. As the protests against increasing inequities between rich and poor spread from Wall Street, its clear that the issue is crucial not least for the understanding of human health. On Wednesday in Rio, in fact, a World Health Organization conference focused on related issues is being attended by high-level health officials from at least 60 nations around the world. Economic inequality is measured by looking at the distribution of wealth and income in a society, not the general wealth of a country. At a basic level, a countrys overall economic success does predict its peoples well-being, but the healthiest and happiest countries in the world are not the richest. Rather, they are countries where wealth is shared widely and more equally. One obvious way in which economic equality may improve health is by reducing barriers to health care among the poor. But it turns out that the health gap exists even in countries with national health services, so the roots of the problem appear to reach deeper than that. Indeed, they may go back to the dominance hierarchies of our primate ancestors. MORE: Awkward Silences: 4 Seconds Is All It Takes to Feel Rejected As studies of wild baboons in Africa have shown, there are certain key side effects of inequality namely, stress. Baboons have a rigidly enforced social hierarchy in which fights to win alpha status are common and higher-ranking males constantly abuse and bully those below them. Not surprisingly, this results in chronically elevated levels of stress hormones in the lower ranks. Chronically high stress hormone levels are bad news, for both humans and baboons. While these hormones can be helpful in short-term fight-or-flight situations, if they are elevated over long periods of time, they increase the risk of virtually all major mental and physical illnesses, including stroke, heart disease, diabetes, depression, infectious disease, many cancers and, of course, all types of addictions. In humans, in fact, differences in health linked to social status which tracks closely with economic status have often been attributed only to addictions

and to the generally bad health habits of the poor, such as eating a lousy diet. But baboons dont have these lifestyle factors and yet increased mortality in the lower ranks is still seen. Human studies bear out the association between low socioeconomic status and ill health. Sir Michael Marmot, professor of epidemiology at University College London, has spent decades looking at the effects of status differences in a population very different from baboons: British civil servants working in the government bureaucracy based in Whitehall Street in London. Marmot found large health differences across the social scale. There are two striking findings. The first was that there was about a threefold difference between the top and bottom in mortality. Thats absolutely enormous, he says. The second was that it wasnt just a difference between the top and bottom; it was what I called a social gradient. There was a stepwise relationship between your socioeconomic position and your health. He adds, Your readers who are not at the bottom [may want to know] that the second from the top had worse health and higher mortality than the top and the third was worse than the second. The effect is much more profound than that seen in baboon societies. As Stanford biologist Robert Sapolsky, who led much of the research in stress in African baboons, once told me: When humans invented inequality and socioeconomic status, they came up with a dominance hierarchy that subordinates like nothing the primate world has ever seen before. Moreover, Marmot points out, the people who were on the bottom in his research were not poor or unemployed. In Whitehall, were not dealing with poverty. Were dealing with people in stable white collar employment and [still we see] this graded relationship between where they are in the hierarchy and health, he says. When Marmot and his colleagues controlled for lifestyle factors like smoking and lack of exercise in the lower socioeconomic groups, the gradient remained. Those things accounted for about a third of the gradient, he says, noting that you have to look for the causes of the causes the reasons that the lower classes might be driven to smoke, drink, take drugs or indulge in sweet, fatty foods. Its now been described the world over, Marmot says. Indeed, in country-to-country comparisons, researchers find that the greater the difference between the richest and the poorest in a society, the worse off everyone in that society seems to be. It looks as if what inequality does is amplifies the effect of social status differences, says Richard Wilkinson, an epidemiologist and co-author of the British bestseller The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger. In countries such as Japan and those in Scandinavia, which have the lowest levels of socioeconomic inequality in the developed world, the populations also enjoy

overall greater life expectancy, lower infant mortality, reduced obesity, heart disease and mental illnesses, and lower rates of murder and addictions, compared with nations with high inequality like the U.K., and even more so, the U.S. Countries with wider equality also have higher levels of academic achievement and happiness. One study in Finland found that mortality rates were twice as high in the poorest people as in the richest, a much less stark difference than that seen in Whitehall, where bottom-of-the-ladder folks had a threefold higher mortality risk than those at the top. Marmot cautions that such comparisons are hard to make accurately and that even in relatively equal countries, some status differences still exist. Still, he says, Fairly detailed comparisons done across Europe suggest that the magnitude of the gradient is less in Nordic countries. So how exactly does inequality lead to so much stress? By degrading our relationships with one another. The most important pathway is the effect of inequality on the quality of social relationships in a society, says Wilkinson. I think the more unequal you get, the more competitive social relationships become, because theres more status competition. And because good relationships are crucial for protecting people from stress, socioeconomic inequality creates an environment in which people with the most stress cant counter its negative health effects. This social competition degrades relationships and erodes trust across the socioeconomic spectrum and not just among those on the bottom. (More equal societies also have higher levels of trust.) Although researchers like Marmot havent been able to study the top 1%, at least one recent finding in baboons should give pause even to the very well-off. The study found that alpha males those at the very peak of the hierarchy were actually just as stressed as their lowest-ranked followers. The least stressed among the baboon troops were the beta males, the No. 2s in the hierarchy. Unlike the alphas, they could chill out and reap the perks of power without constantly having to fight off challengers. Even when youre at the top, then, inequality affects you and a gradient always remains for those who are successively lower down. But its not inevitable: in one baboon troop Sapolsky studied, rank appeared not to affect stress and health. What happened there was that the meanest top-ranked animals had died off due to eating tainted meat, leaving the mellower ones in charge, which reduced rank-related bullying. MORE: Why Being Beta Might Be Better In the U.S., inequality has been rising since the 1980s. Between WWII and Ronald Reagans election to the presidency, average income grew by $19,000. The bottom 90% of the country received 65% of that increase.

Between 1981 and 2008, however, average income grew by around $12,000. About 96% of that went to the top 10% richest people in the country. The ratio of pay between CEOs and average workers also became much more extreme over the same time period: in 1980, it was around 35 to 1. Today it is about 185 to 1. If we want to be healthier and happier, we cant ignore inequality. Read more: How Economic Inequality Is (Literally) Making Us Sick | TIME.com http://healthland.time.com/2011/10/19/how-economic-inequality-is-literallymaking-us-sick/#ixzz2mIRFctsQ

'Is Facebook real?' China's internet users ask in frustration as Iran lifts its ban Tuesday, 17 September, 2013, 11:02am NewsChina Insider CENSORSHIP Amy Li chunxiao.li@scmp.com China, along with North Korea, is among the few countries which still block Facebook and Twitter Chinas online community brimmed with disappointment - if not despair - on Tuesday after online media reported that Iran had granted its citizens access to Facebook and Twitter. Both sites had been walled off from Iranian users since 2009. This leaves China, along with its neighbour North Korea, among the very few countries which still block Facebook and Twitter. Iranians are now returning to Facebook, yet we Chinese haven't even met Facebook, one microblogger commented on Weibo. What are Facebook and Twitter? Do they really exist?, one frustrated blogger commented. Is this how China demonstrates its 'confidence'?, another blogger quipped, referring to the new leadership's slogan of "self-confidence". Some internet users in China visit Twitter and Facebook via paid VPN [virtual private network] services. Yet some complain that VPNs had also been banned and could be unstable. Others commented that Chinese social networking sites like Weibo had thrived due to the absence of competition from Facebook and Twitter. They argued that the government had blocked the international websites to benefit domestic players.

This happened only days after Facebook's Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg met with Cai Mingzhao, head of China's State Council Information Office in Beijing last week. The two parties discussed Facebooks role in helping Chinese enterprises expand overseas, on top of other cooperative items, said reports. Though it looks unlikely that China will unblock the site soon, a Wall Street Journal report said the meeting [1]showed China has become "an increasingly important source of advertising dollars for US tech companies". Chinas censors have said on numerous occasions there was no internet censorship in China.

When China's state media reported Myanmar lifting its ban on Facebook in March, it said: "Only four countries in the world still ban the website: North Korea, Cuba, Iran and another country". [2] Readers, besides poking fun at the ambiguous report, also pointed out that Facebook was not blocked in Cuba, even though access to the internet in the communist country was rare and expensive.

Graduate careers: the importance of employability skills Qualifications are fine, but most employers are now looking for a more human touch You might have a degree, perhaps a technical qualification and a bit of work experience on your CV but have you promoted your soft skills? Do you even know what they are? Soft skills sometimes known in work-speak as "employability skills" are becoming increasingly important to graduate recruiters sifting through the CVs of a growing pool of similar looking applicants, according to experts. While hard skills refer to things such as academic qualifications, soft skills include communication ability, teamworking, time management, problem solving and attitude to work. A recent report by the Work Foundation concluded that the long-term shift from production to a service-driven economy has made soft skills increasingly important for people seeking their first job. Findings from the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) back this up. Of more than 1,000 HR professionals surveyed, the vast majority said that, aside from an increased need for more workers, better employability skills would be more likely to encourage them to hire young people than financial incentives, such as those from the government. The good news is that, while many soft skills are inherent, others can be learned. "You can train yourself just as you can in hard skills," says Soraya Pugh, head of graduate at recruitment consultancy FreshMinds Talent. "If you are shy, for example, get involved in debating societies and other clubs at school and university. There are also courses on communication skills that can not only teach you some soft skills but help you demonstrate to employers self-awareness and initiative simply by the fact you have signed up." Ben Willmott, head of public policy at the CIPD, believes the best way of demonstrating such skills is to get some work experience. "It is in every young person's interest to try and gain experience that exposes them to the workplace," he says. "This is not only because of the obvious benefits in terms of hard skills. "Our research suggests that the main benefit is that it helps them to develop soft skills." Recruitment experts agree that graduates applying for jobs can start to highlight their soft skills as early as the CV stage. Soft skills don't need to be listed under a separate heading on a CV this could look naff but need to be demonstrated through examples. It's not good enough to say you are a good communicator, you need to say why.

Rebecca Jones, business coach and author of Business in Red Shoes, says she speaks to a lot of graduates who struggle to think of what to put on their CV. "They then start blagging rather than making the best of what they have got and that lands them in all sorts of trouble," she says. "Soft skills are what make your personal brand but you need to think about them. Instead of thinking, for example, 'I have only worked at McDonald's', think 'What did working at McDonald's teach me?'" Graduates who are not particularly assertive might worry that desirable soft skills can best be demonstrated by those with more confidence. But Rob Johnson, managing director at Instep, a training and development provider says one of the most important can be the hardest to master. "This is the ability to listen," he says. "A good candidate will demonstrate that ability from the first phone call they make, right through the interview process. Your ability to articulate clearly and concisely is secondary to your ability to listen to the questions and think carefully about your answers."

22 November 2013 Last updated at 00:48 GMT No siblings: A side-effect of China's one-child policy By Celia Hatton BBC News, Beijing What's it like to grow up in a world where no-one has brothers or sisters? Are siblings really that important? Researchers have been asking those questions for years - and China, with its famous one-child policy, has been a good place to look for an answer. Chinese families used to have an average of four children each, but life changed radically in 1979, when a law was introduced dictating that most parents could only have one child. Last week, we learned that the policy will now be relaxed, after being enforced across the world's most populous country for more than a generation. "On the township roads, there are slogans written on flamboyant red banners, telling people to have fewer children and raise more pigs," says art photographer Fan Shi San, recalling a recent trip to the impoverished province of Gansu. Fan, himself an only child, takes photographs of single children alongside their "phantom" brothers or sisters - the siblings they never had. "Most of my audiences don't realise they have a special identity," he explains, noting that many parents even stopped questioning why they couldn't have more than one child and forgot that things had ever been different. In 1979, when the policy was first unveiled, the new rules were a major adjustment for those accustomed to large families. But children growing up under the policy were unaware of this. And in the early years, the parents of most new single children came from large families - so instead of siblings the children were able to forge close relationships with cousins. Since 1997, sociologist Vanessa Fong of Amherst College in Massachusetts has followed a group of 2,273 Chinese "singletons" as she calls them. Every year, she interviews and surveys between 600 and 1,300 of the original group so she can track how their lives have been affected by growing up without siblings. To begin with, the very notion of "sibling" was a hard one for the children to grasp - a task made more difficult by the Chinese tendency to use the term for "brother" or "sister" when talking about cousins. Even when the children were in their teens, she would have to explain the difference to this group of people that had never encountered genetic siblings. "They'd say, 'Well, yes, I have many brothers and sisters.' And I'd say, 'How did that happen? Most people have no siblings.' And they'd say, 'Oh, I'm talking about my aunts' children'." The first singletons born under the one-child policy experienced other changes, too, apart from the absence of brothers and sisters. "Every family suddenly had a huge amount of discretionary income to invest in education and also in consumption," Fong explains. The resources that had been spread among several children in past generations were now focused on one child. The result - China's new singletons were more educated than generations before them. And Chinese education costs soared overnight. In the past, parents would usually choose just one of their children to progress in school. But after the onechild policy came into practice, each single child shouldered this focused pressure from two parents.

Ge Yang, a 32-year-old woman who grew up in Beijing, says the unflinching, relentless attention she received from her father, a driver, and her mother, an accountant, altered the course of her life. "If my parents had had other children, they would have paid less attention to me, in which case I might have spent more time and energy doing things that interest me. Chinese parents of my parents' generation like to plan life for their children," she explains. Ge now works as a pharmaceutical sales representative, a solid middle-class job. But things might have been different, she says, if she had had siblings to share the burden of her parents' expectations. She might have chosen a different career, or moved away from Beijing. "I think if I had another chance, I might choose to work in the tourism industry, or live in another city," she muses. "But as a single child, I have the responsibility to look after my parents. I couldn't leave my city. I need to be with them. This is something I cannot change." Nonetheless, she sees her singleton status in a positive light. "As an only child, I have my parents' love all to myself," she says firmly. "I don't want to share my parents with others." But what about Little Emperor Syndrome - the notion that China's children would grow up spoiled and self-centred. It was widely feared, but a number of studies - including many conducted by Chinese researchers - have failed to turn up any nasty personality traits among those who grew up in China's one-child families. There's no real evidence that China's singletons are any different than other children, they argue. But other studies contend that China's singletons are different. A study of only children in Beijing released by a group of Australian researchers this year used a series of games and surveys to test behavioural traits. The study attempted to unveil the subjects' real personalities by using games tied to real financial rewards, explains University of Melbourne economist Nisvan Erkal. "What we found was that people born after the policy, and who are single children because of the policy are significantly less trusting, less trustworthy, more risk averse and less competitive," he says. "From the surveys, we find they are also more pessimistic and less conscientious." Those born in the later stages of the one-child policy will provide researchers with even richer material. While children born in the 1970s and 1980s were usually surrounded by large extended families, those born more recently will typically have been born to parents who were single children themselves. With fewer cousins, aunts and uncles in the mix, children grow up in much smaller families than before. An increasing tendency for people to move home for the sake of a job also makes it more likely single children will grow up without close ties to their grandparents, or even childhood friends, notes the sociologist, Vanessa Fong. "China has changed a lot, so relationships are not as intimate as before," she explains. "In previous generations, people were not able to move to other cities or other countries. Now, there is a lot more migration, both within China and between China and other countries." Ge understands that concern. Her three-year-old daughter is experiencing a much different childhood than the generations before her.

"My child will have very few stable friends. She will have many new friends as she grows up, but she will have very few long-term friends who grow up together," she ays. Under the new relaxation of the one-child policy, Ge and her husband qualify for a second child. However, she knocks down that idea with a quick wave of her hand. A second child would be too expensive, she explains, if she wants to be able to afford a good lifestyle. "It is not that we don't want to raise more children, it is that we cannot create that many opportunities for them. If I cannot create that much opportunity for my children, I think that my children will feel lost in competition against other children," she says. Although the one-child policy is still in place for many in China, it is possible that one day in the not-too-distant future, China's one-child generation will become a chapter in the country's history books. But even when that happens, the ultimate verdict as to whether China's singletons were hurt by the policy, or benefited from it, may still be the subject of debate.

You might also like

- Anxiety at Work: 8 Strategies to Help Teams Build Resilience, Handle Uncertainty, and Get Stuff DoneFrom EverandAnxiety at Work: 8 Strategies to Help Teams Build Resilience, Handle Uncertainty, and Get Stuff DoneRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (2)

- From Bully to Bull's-Eye: Move Your Organizaion Out of the Line of FireFrom EverandFrom Bully to Bull's-Eye: Move Your Organizaion Out of the Line of FireNo ratings yet

- No Time To Be Nice at Work - The New York TimesDocument7 pagesNo Time To Be Nice at Work - The New York TimesW MoeNo ratings yet

- BC AssingmentDocument13 pagesBC AssingmentMansi VermaNo ratings yet

- Human RelationsDocument47 pagesHuman RelationsDaisy Mendiola100% (3)

- Work Life BalanceDocument16 pagesWork Life BalanceChandrashekharCSKNo ratings yet

- Be Yourself GuideDocument1 pageBe Yourself GuidemanishdgNo ratings yet

- Positivity Pays: Planting Seeds of Positivity in a World Full of WeedsFrom EverandPositivity Pays: Planting Seeds of Positivity in a World Full of WeedsNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document5 pagesChapter 1Kylle CalipesNo ratings yet

- Assessment Task 3..Document11 pagesAssessment Task 3..parul sharmaNo ratings yet

- March 2021 Whitepaper v1.1Document11 pagesMarch 2021 Whitepaper v1.1Nely BorzaNo ratings yet

- Research EssayDocument14 pagesResearch EssayRaiha BilalNo ratings yet

- Surfing the Paradoxes of Everyday Transformation: Flourishing in the Context of an Emerging NormalFrom EverandSurfing the Paradoxes of Everyday Transformation: Flourishing in the Context of an Emerging NormalNo ratings yet

- How Full Is Your Bucket - PdaDocument7 pagesHow Full Is Your Bucket - PdaBiswa Prakash NayakNo ratings yet

- Get Better: 15 Proven Practices to Build Effective Relationships at WorkFrom EverandGet Better: 15 Proven Practices to Build Effective Relationships at WorkNo ratings yet

- Group Members: Saad Ahmed (092) M. Usman Inam (077) Aiza Hussain Rana (008) Haseeb Ali (035) Faisal Zafar (029) BBA-3BDocument12 pagesGroup Members: Saad Ahmed (092) M. Usman Inam (077) Aiza Hussain Rana (008) Haseeb Ali (035) Faisal Zafar (029) BBA-3BSayyed SofianNo ratings yet

- Career guidance desperately needed in times of coronavirusDocument5 pagesCareer guidance desperately needed in times of coronavirusRomeo CapulongNo ratings yet

- Palle Sree Nikhil - Bba LLB - 2021. 3Document7 pagesPalle Sree Nikhil - Bba LLB - 2021. 3Nikhil BobbyNo ratings yet

- Rhetorical PatternsDocument10 pagesRhetorical PatternsAlly MaurerNo ratings yet

- Social Work Research PaperDocument7 pagesSocial Work Research Paperruvojbbkf100% (1)

- Government SideDocument2 pagesGovernment SideDonna Jayne AlianzaNo ratings yet

- Social Anxiety Thesis StatementDocument4 pagesSocial Anxiety Thesis Statementafloattaxmxufr100% (2)

- Magical Thinking Con Be Re He or Hi AdiDocument11 pagesMagical Thinking Con Be Re He or Hi AdiAna Laura CermeloNo ratings yet

- Case IncidentDocument14 pagesCase Incidenteka triyaniNo ratings yet

- Extraordinary Influence: How Great Leaders Bring Out the Best in OthersFrom EverandExtraordinary Influence: How Great Leaders Bring Out the Best in OthersNo ratings yet

- The Leader's Brain: Enhance Your Leadership, Build Stronger Teams, Make Better Decisions, and Inspire Greater Innovation with NeuroscienceFrom EverandThe Leader's Brain: Enhance Your Leadership, Build Stronger Teams, Make Better Decisions, and Inspire Greater Innovation with NeuroscienceRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Essay About TeachersDocument7 pagesEssay About Teachersafhevpkzk100% (2)

- HappyDocument9 pagesHappyRoxana CabreraNo ratings yet

- Engaging EmployeesDocument26 pagesEngaging EmployeesingaNo ratings yet

- Economics of Happiness Article Financial TimesDocument4 pagesEconomics of Happiness Article Financial TimesAijana TursunovaNo ratings yet

- Burnout Is About Your Workplace, Not Your PeopleDocument9 pagesBurnout Is About Your Workplace, Not Your PeoplePiter KiiroNo ratings yet

- Eight Ways to Find More Meaning at WorkDocument4 pagesEight Ways to Find More Meaning at WorkJulia DarwichNo ratings yet

- The Addictive Organization: Why We Overwork, Cover Up, Pick Up the Pieces, Please the Boss, and Perpetuate SFrom EverandThe Addictive Organization: Why We Overwork, Cover Up, Pick Up the Pieces, Please the Boss, and Perpetuate SNo ratings yet

- The ASTD Management Development Handbook: Innovation for Today's ManagerFrom EverandThe ASTD Management Development Handbook: Innovation for Today's ManagerNo ratings yet

- Case IncidentDocument4 pagesCase IncidentMeita ArifanyNo ratings yet

- Eat Sleep Work Repeat: 30 Hacks for Bringing Joy to Your JobFrom EverandEat Sleep Work Repeat: 30 Hacks for Bringing Joy to Your JobRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Work-Life Balance in the IT SectorDocument21 pagesWork-Life Balance in the IT Sectorjapulin9No ratings yet

- Excerpt From The by 8th Habit Stephen CoveyDocument4 pagesExcerpt From The by 8th Habit Stephen CoveyShakerulTazuNo ratings yet

- Corp Gov ProjectDocument14 pagesCorp Gov ProjectHorace Centrado ThomasNo ratings yet

- Extraverted leaders are not always effective, especially with proactive employeesDocument3 pagesExtraverted leaders are not always effective, especially with proactive employeesjjxlNo ratings yet

- Signals: How Questioning Assumptions Produces Smarter DecisionsFrom EverandSignals: How Questioning Assumptions Produces Smarter DecisionsNo ratings yet

- Annihilate Stress and Anxiety: 21 Proven Strategies for a Balanced LifeFrom EverandAnnihilate Stress and Anxiety: 21 Proven Strategies for a Balanced LifeNo ratings yet

- Innovation Change Management Articles tcm36-68774Document20 pagesInnovation Change Management Articles tcm36-68774eliasNo ratings yet

- Good Research Paper Topics Social WorkDocument7 pagesGood Research Paper Topics Social Workgvyns594100% (1)

- Toxic Workplace EssayDocument9 pagesToxic Workplace Essayapi-609554661No ratings yet

- Thomas Sowell - Discrimination and Disparities (2018)Document369 pagesThomas Sowell - Discrimination and Disparities (2018)Rafael Henrique AssisNo ratings yet

- Why Women Make Better LeadersDocument3 pagesWhy Women Make Better LeadersJulian Lennon DabuNo ratings yet

- Toxic Workplace!: Managing Toxic Personalities and Their Systems of PowerFrom EverandToxic Workplace!: Managing Toxic Personalities and Their Systems of PowerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- Why Leaders Need To Understand Personality: Quality ControlDocument5 pagesWhy Leaders Need To Understand Personality: Quality ControlAjay Kumar RamachandranNo ratings yet

- Toward Human SustainabilityDocument8 pagesToward Human SustainabilityS ChettiarNo ratings yet

- Power, Capriciousness, and Consequences: The Costs of Unpredictable LeadershipDocument2 pagesPower, Capriciousness, and Consequences: The Costs of Unpredictable LeadershipMahreenAlamNo ratings yet

- The Toxic Boss Survival Guide - Tactics for Navigating the Wilderness at WorkFrom EverandThe Toxic Boss Survival Guide - Tactics for Navigating the Wilderness at WorkRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- EconomicSociology ChapterText Fall2021 20210906 Pp9bhqDocument30 pagesEconomicSociology ChapterText Fall2021 20210906 Pp9bhqRyma UzairNo ratings yet

- How to Build a Thriving Culture at Work: Featuring The 7 Points of TransformationFrom EverandHow to Build a Thriving Culture at Work: Featuring The 7 Points of TransformationNo ratings yet

- Summary and Analysis of Smarter Faster Better: The Secrets of Being Productive in Life and Business: Based on the Book by Charles DuhiggFrom EverandSummary and Analysis of Smarter Faster Better: The Secrets of Being Productive in Life and Business: Based on the Book by Charles DuhiggRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Adapted From Kay HymowitzDocument2 pagesAdapted From Kay HymowitzmadalinaNo ratings yet

- Halloween ClozeDocument1 pageHalloween ClozeAbeeramee SubramaniamNo ratings yet

- IeltsDocument1 pageIeltslavvvenderNo ratings yet

- Sample Executive Summary9 H9hui9hih 9Document1 pageSample Executive Summary9 H9hui9hih 9lavvvenderNo ratings yet

- SDFGD FSFG SDFGDocument1 pageSDFGD FSFG SDFGlavvvenderNo ratings yet

- IeltsDocument1 pageIeltslavvvenderNo ratings yet

- IeltsDocument1 pageIeltslavvvenderNo ratings yet

- 分享英文諺語大全Document97 pages分享英文諺語大全Katherine ChungNo ratings yet

- Irregular Past Tense Verbs Clo ZeDocument1 pageIrregular Past Tense Verbs Clo ZeMark Ogaya100% (3)

- Siej Inpsgrnagrnpa SRN Tpakernt PDocument2 pagesSiej Inpsgrnagrnpa SRN Tpakernt PlavvvenderNo ratings yet

- GCSE Mathematics A Scheme of Work Three YearDocument158 pagesGCSE Mathematics A Scheme of Work Three YearlavvvenderNo ratings yet

- IeltsDocument1 pageIeltslavvvenderNo ratings yet

- IeltsDocument1 pageIeltslavvvenderNo ratings yet

- IeltsDocument1 pageIeltslavvvenderNo ratings yet

- IeltsDocument1 pageIeltslavvvenderNo ratings yet

- IeltsDocument1 pageIeltslavvvenderNo ratings yet

- IeltsDocument1 pageIeltslavvvenderNo ratings yet

- IeltsDocument1 pageIeltslavvvenderNo ratings yet

- IeltsDocument1 pageIeltslavvvenderNo ratings yet

- IeltsDocument1 pageIeltslavvvenderNo ratings yet

- Adapted Sports & Recreation 2015: The FCPS Parent Resource CenterDocument31 pagesAdapted Sports & Recreation 2015: The FCPS Parent Resource CenterkirthanasriNo ratings yet

- Spiegel Et Al 1999 Psycho OncologyDocument12 pagesSpiegel Et Al 1999 Psycho Oncologyfatimaramos31No ratings yet

- The Payment of Bonus Act 1965 PDFDocument30 pagesThe Payment of Bonus Act 1965 PDFappu kunda100% (1)

- Betriebsanleitung Operating Instructions GLOBALlift R ATE V01R00 EN 2Document14 pagesBetriebsanleitung Operating Instructions GLOBALlift R ATE V01R00 EN 2Alexandru RizescuNo ratings yet

- PunchesDocument25 pagesPunchesJhoanne NagutomNo ratings yet

- Spxflow PDFDocument317 pagesSpxflow PDFAnonymous q2iHVf100% (3)

- PDI Quality Manual Rev 4 - 1.0 Table of ContentsDocument1 pagePDI Quality Manual Rev 4 - 1.0 Table of ContentslouieNo ratings yet

- Ascha_ASJ19_Nonsurgical Management of Facial Masculinization and FeminizationDocument15 pagesAscha_ASJ19_Nonsurgical Management of Facial Masculinization and Feminizationallen.515No ratings yet

- Caffeine's Effect on Daphnia Heart RateDocument2 pagesCaffeine's Effect on Daphnia Heart RateMianto NamikazeNo ratings yet

- CCE Format For Class 1 To 8Document5 pagesCCE Format For Class 1 To 8Manish KaliaNo ratings yet

- Proforma For Iphs Facility Survey of SCDocument6 pagesProforma For Iphs Facility Survey of SCSandip PatilNo ratings yet

- The Human Excretory System: A 40-Character GuideDocument3 pagesThe Human Excretory System: A 40-Character GuideMelvel John Nobleza AmarilloNo ratings yet

- Research Journal DNA PolymeraseDocument12 pagesResearch Journal DNA PolymeraseMauhibahYumnaNo ratings yet

- Humiseal Thinner 73 MSDSDocument3 pagesHumiseal Thinner 73 MSDSibnu Groho Herry sampurnoNo ratings yet

- Grade 6 School Lesson on Propagating Trees and Fruit TreesDocument10 pagesGrade 6 School Lesson on Propagating Trees and Fruit TreesGhrazy Ganabol LeonardoNo ratings yet

- Case Study - BronchopneumoniaDocument45 pagesCase Study - Bronchopneumoniazeverino castillo91% (33)

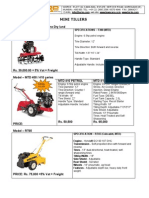

- Optimize soil preparation with a versatile mini tillerDocument2 pagesOptimize soil preparation with a versatile mini tillerRickson Viahul Rayan C100% (1)

- Gastronomia 10 Competition GuideDocument21 pagesGastronomia 10 Competition Guidefpvillanueva100% (1)

- Pyrogen and Endotoxins GuideDocument13 pagesPyrogen and Endotoxins GuideAnil Kumar GuptaNo ratings yet

- Tle 7 - 8 Curriculum MapDocument11 pagesTle 7 - 8 Curriculum MapKristianTubagaNo ratings yet

- GarrettDocument2 pagesGarrettAndrey MarviantoNo ratings yet

- Cooling & Heating: ShellmaxDocument3 pagesCooling & Heating: Shellmaxvijaysirsat2007No ratings yet

- Respiratory Medicine 1 50Document33 pagesRespiratory Medicine 1 50Ahmed Kh. Abu WardaNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Academic Research Vol. 4. No. 4. July, 2012Document5 pagesInternational Journal of Academic Research Vol. 4. No. 4. July, 2012Sulaiman MukmininNo ratings yet

- Using Casts For ImmobilizationDocument17 pagesUsing Casts For Immobilizationmpmayer2No ratings yet

- Changes in Demand and Supply of Face Masks Under CovidDocument3 pagesChanges in Demand and Supply of Face Masks Under CovidHanh HoangNo ratings yet

- URINALYSISDocument6 pagesURINALYSISmaeNo ratings yet

- Observations of Children's Interactions With Teachers, PeersDocument25 pagesObservations of Children's Interactions With Teachers, PeersMazlinaNo ratings yet

- M Shivkumar PDFDocument141 pagesM Shivkumar PDFPraveen KumarNo ratings yet

- Oral Dislocation Rehabilitation Program - FirstDocument2 pagesOral Dislocation Rehabilitation Program - FirstPriyaki SebastianNo ratings yet