Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Medicion Migra Irregular

Uploaded by

yosiquiOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Medicion Migra Irregular

Uploaded by

yosiquiCopyright:

Available Formats

MIGRATION

Edited by Elzbieta Gozdziak, Georgetown University

doi:10.1111/j.1468-2435.2011.00699.x

Measuring Irregular Migration and Population Flows What Available Data Can Tell

Albert Kraler* and David Reichel**

ABSTRACT

Wild assumptions, estimates and number games are made in regard to irregular migration ows. While the numbers cited are, in fact, often dated and of unclear origin, reports use such numbers to suggest a rise in irregular migration; they also usually assume that irregular entry and, to some extent, overstaying are the only signicant pathways into irregularity. To properly account for irregular migration ows, however, both in- and outows, as well as the complex ways of becoming (or ceasing to be) an irregular migrant, have to be included. Thus, apart from irregular migration ows in the narrow sense, like unlawful entry and emigration of persons (unrecorded returns, registered voluntary returns and deportations), other ows notably status-related inows (overstaying, withdrawal of residence status, rejection of asylum claims), status-related outows (regularisation, ex lege changes of the legal status of irregular migrants, etc.) and ows related to vital events (births and deaths), must be considered. The article provides a critical appraisal of available data sources, indicators, estimates and methods to estimate irregular migration ows. In the context of a case study, we then analyse statistics of apprehensions at the EUROPEAN UNIONs external borders in Eastern Europe as indicators of geographical ows migration ows in the narrow sense arguing that despite the many limitations of the available data, the data can nevertheless be used as indicators of certain trends.

INTRODUCTION

The ght against irregular migration has been a priority of European Union policies on immigration and asylum ever since the communitarisation of

* International Centre for Migration Policy Development. ** International Centre for Migration Policy Development. 2011 The Authors International Migration 2011 IOM International Migration Vol. 49 (5) 2011 ISSN 0020-7985

Published by Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK, and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA.

98

Kraler and Reichel

migration policies in the wake of the Amsterdam Treaty 1997 and the rst veyear policy plan in the area of migration and asylum, announced at the Tampere summit in December 1999. Intergovernmental cooperation on irregular migration at the European Union level started considerably earlier and preceded the formal communitarisation of migration and asylum policy by more than a decade (Hofmann et al., 2004; Kammel, 2006; Schwenken, 2006: 96ff). While irregular migration has been a concern for policymakers and public authorities since well before the 1990s (Karakayali, 2008; Schrover et al., 2008), it is the combined effect of the geopolitical changes after the collapse of the communist regimes in Eastern Europe, the massive rise in immigration to the European Union in the late 1980s (see Figure 1) and in particular, the increase of asylum- and conict-related migration, which made irregular migration a central concern during the 1990s, reected not only in a variety of policy initiatives but also in the increasing efforts to compile and analyse relevant data. In the context of the immigration crisis of the early 1990s, the general perception was that immigration had become increasingly uncontrollable and that the share of migrants entering the European Union in an irregular manner was rapidly growing. Figures put forward for the European Union alternately spoke of 500,000 irregular annual entries (Ghosh, 1998: 10; quoting an unreferenced

FIGURE 1 NET MIGRATION TO THE EUROPEAN UNION, 19612009 (IN MILLIONS)

2500000 2000000 1500000 1000000 500000 0 -500000 -1000000

1961 1963 1965 1967 1969 1971 1973 1975 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009

European Union (27 countries).

European Union (25)

Source:

Eurostat (estimated net migration), own presentation.

2011 The Authors. International Migration 2011 IOM

Measuring irregular migration and population ows

99

US government report as reported in the January 1996 edition of the Migration News newsletter and presumably referring to the mid-1990s) or 250,000 to 350,000 irregular entries per annum (Widgren, 1994; see also Iglicka, 2008: 13f).1 These two gures quickly took on a life of their own and have survived until the very present. For instance, a recent impact assessment commissioned by the European Commission in the context of the preparation of the Employer Sanctions Directive (GHK, 2007) repeats these gures, but instead of quoting the original sources, it refers to more recent studies quoting the gures, implicitly suggesting that the estimates are similarly of a recent date. In addition, though the original estimates referred to an only vaguely dened Western Europe and the member states constituting the European Union and EFTA in 1994, they are suddenly being used to refer to the European Union of 25 member states and then 27 member states after 2005 and 2007, respectively. Finally, in the impact assessment, the original estimates of the number of irregular entries per year have become estimates of net ows (i.e. estimates of the net increase of the stock of the irregular migration population). Apprehension statistics collected at the European level in the framework of the CIREFI2 -data collection until 2008 have since been replaced by Enforcement of Immigration Legislation (EIL) statistics collected by the Commissions statistical agency Eurostat and statistics on apprehended migrants on Europes external borders, collected by FRONTEX.3 These statistics may seem to provide a more solid basis for making statements on irregular migration ows, but are also problematic, not least since it is not entirely clear how the data published at the European-level relate to data published at the national level.

DEFINING IRREGULAR MIGRATION AND POPULATION FLOWS

Irregularity is notoriously difcult to dene as it involves a variety of dimensions, including the legal status at and after entry, the link between residence status and employment, and whether persons are documented known to the authorities or not (cf. Baldwin-Edwards and Kraler, 2009: 14). In addition, the expansion of freedom-of-movement rights of European Union citizens and their family members, the latest waves of EU enlargement and the evolution of a secure residence status for third-country nationals who are long-term residents all carry important implications for the meaning of irregularity and effectively limit the notion of irregularity to specic categories of third-country nationals without reasonable claims to a secure legal status. Following Vogel and Jandl (2008: 7) irregular or undocumented residents [can be] dened as residents without any legal residence status in the country they are residing in, and those whose presence in the territory if detected may be subject to termination through an order to leave and or an expulsion order because of their activities. This denition excludes all asylum seekers, who have a right to stay for the purpose of the asylum procedure, and persons whose removal is formally suspended, such as tolerated persons in Germany.

2011 The Authors. International Migration 2011 IOM

100

Kraler and Reichel

The denition of irregular population and migration ows4 is arguably more difcult, not only because there are different types of ows into and out of an irregular status (explained in more detail below), but also because of the temporal disjuncture between individual ow events and the actual change into an irregular condition, where it is hard to dene what point exactly constitutes the ow into and out of irregularity. The following example may illustrate the point: in the current context, the majority of asylum seekers enter European countries irregularly, although they have a legal right to stay once admitted to the asylum procedure. Thus, while their entry may be irregular, that particular inow does not contribute to the stock of irregular migrants. On the other hand, asylum seekers whose asylum claim is later rejected become irregular residents almost by denition, if no humanitarian or other reasons justifying their stay can be invoked. Finally, the time passing between the three events determining the status of the migrant physical (irregular) entry of a territory of an EU member state, submission of an asylum claim and refusal (or positive decision of an asylum claim) may range from a few days to several years. For the purpose of this article, we dene irregular population and migration ows as events or processes that inuence the size and composition of the stock of the irregular migrant population in a particular geographic unit and over a particular period of time. Inows contribute to the stocks of irregular migrants and outows reduce them. Following Vogel and Jandl (2008) and graphically shown in Figure 2, below, three basic types of irregular migration ows can be distinguished: (1) irregular migration ows, or geographic ows in the terminology of Vogel and Jandl, (2) vital events affecting the irregular migrant population or demographic ows, and (3) status-related ows. Conceptually, this approach follows standard demographic approaches to population change and mirrors the terminology used for the demography of the foreign resident population. The stock of the legal foreign resident population is also inuenced by the same types of ows: migration (immigration and emigration), vital events (birth and deaths of foreign residents) and status related ows (in the case of foreign nationals, status related ows essentially consist of the acquisition and loss of citizenship, but could also include loss of residence permits or regularisation). Our model of irregular population change helps to differentiate different components of population change and essentially serves a statistical purpose, namely to identify and classify ow indicators regarding the irregular migrant population according to different components of population change. The model thus does not seek to explain patterns, types or reasons for irregular migration. Our aims here are more modest: to provide a heuristic model to better understand changes of the size of the irregular migrant population from a demographic point-of-view and to contribute to a better understanding of related indicators. In particular, our model helps to highlight that changes of the size of the irregular migrant population are not necessarily, directly related to irregular forms of movement. This said, even non-migratory ows status related and demographic ows are ultimately linked to human mobility. The nature and strength of this link, however, is subject to considerable variation.

2011 The Authors. International Migration 2011 IOM

Measuring irregular migration and population ows

101

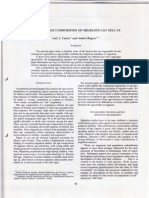

FIGURE 2 IRREGULAR MIGRATION FLOWS

INFLOWS Stocks of migrants in an irregular status

OUTFLOWS

Migration flows

(emigration, i.e. return, onward migration to a third country, removal)

Migration flows

(immigration, i.e. Irregular entrance)

Total Outlfows

Total Inflows

Demographic flows (vital events)

(Births)

Demographic flows (vital events)

(Deaths)

Status related flows

(Overstaying, status withdrawal, temporary lack of legal status)

Status related flows

(Regularisations)

Stocks of migrants with regular status, temporarily admitted persons (e.g. asylum seekers) and tolerated persons

Source: Figure adapted from Vogel and Jandl, 2008: 11; Kraler, 2009: 10.

Irregular migration ows, or geographic ows, concern actual geographical migration movements, for example, physical movement involving the crossing of an international border. Irregular inows concern unauthorised entries into countries over national borders. Geographical outows involve persons who leave a country where they have been staying in an unauthorised manner. Geographical outows involve all forms of physical exit, including onward migration (secondary migration), unregistered voluntary return and registered voluntary return and removal. Demographic ows (vital events) concern births and deaths of persons in an irregular situation. Births increase the stock of the irregular migrant population whereas deaths decrease the stock of irregular residents. With respect to birth into irregularity, two situations may be distinguished, namely (1) children born to parents in an irregular situation and (2) children born to parents where at least one parent has a legal residence status. In the former case, newborn children are almost automatically irregular residents, as their right to residence derives from the right to residence of their parents, except in countries with strong jus soli elements in citizenship legislation (such as Ireland until recently) or other special provisions for minors (such as in Portugal; see Dzhengozova, 2009: 421). In the second case of children born to parents where at least one parent

2011 The Authors. International Migration 2011 IOM

102

Kraler and Reichel

has a legal residence status, children often have a strong claim to legal residence, even if they lack proper documentation and even if one parent may be irregularly staying. Finally, there are several status-related modes of transitions from regularity to irregularity and vice versa, which in our classication can be interpreted as inows and outows from the stock of irregular migrants, respectively. Status-related inows concern migrants who lose their right to reside in the country of residence and remain there. In principle, ve distinct status-related inows into irregularity can be distinguished: (1) the overstaying of a visa or a residence permit, (2) a negative decision in a status determination procedure, notably in the context of the asylum system, (3) a withdrawal of a residence status, for example, because of a conviction for a serious criminal offence or in the course of a routine review of a persons refugee or subsidiary protection status,5 (4) a non-renewal of a residence permit because residence requirements are no longer met or conditions of residence have been breached, and (5) a temporary lack of a legal status because of delays in processing applications for (renewal of) residence permits. Status-related outows concern persons in an irregular status who obtain a legal status through some form of regularisation of their stay (see Baldwin-Edwards and Kraler, 2009; Kraler, 2009). Three basic types of regularisation or status-related transitions from irregularity to regularity can be distinguished: (1) formal regularisations where regularisation of irregular residents is an explicit objective of policy measures, (2) regularisation by operation of the law, for example, by acquiring freedom of movement rights through ones countrys accession to the European Union, by being granted refugee or subsidiary protection status or by obtaining a right to residence through marriage to a legal resident, notably through marriage to a citizen or an EU-citizen, and nally (3) informal regularisations concerning persons who acquire a legal residence status on an ad-hoc basis and in contravention of normal admission procedures foreseen by national authorities (Kraler, 2009: 11, 15). As outlined above, we dene irregular migration and population ows in relation to irregular migrant stocks. According to this conceptualisation of irregular migration ows, changes of the stocks of irregular residents can be interpreted as net irregular migration ows. It is important to bear in mind, however, that net irregular migration ows reect all components of the demographic balance of the irregular migrant population births, deaths, irregular immigration and emigration, and status-related inows and outows and not just border crossings. Irregular migration should not be seen as completely detached from legal migration. Indeed, in a biographical perspective, irregularity seems to be largely of a transitional nature. Conversely, many legal migrants have experienced periods of partial or complete irregularity. Status transitions, therefore, seem to

2011 The Authors. International Migration 2011 IOM

Measuring irregular migration and population ows

103

constitute an important dimension of irregular migration dynamics (see McKay et al., 2009).

EXISTING RESEARCH AND METHODS MEASURING IRREGULAR MIGRATION AND POPULATION FLOWS WHAT DO WE KNOW?

In many respects, the problems in quantifying irregular migration and population ows are not so different from the problems encountered in adequately measuring ows affecting the legal foreign resident population. This, in principle, concerns all three types of ows. However, in the case of the legal resident, foreign population measurement problems are arguably less pronounced in regard to demographic ows and status related ows and more pronounced in regard to migration ows. In regard to the latter, a variety of recent studies (see Kupiszewska et al., 2010; Nowok, 2006) point to the many problems in producing comparable and reliable statistics on both immigration and emigration. One of the key issues in measuring migration is the denition of migration which ows should be counted as migration events and which should not. The key distinction here is between non-migratory movements, usually dened as movements involving less than three months of stay, and migratory movements (temporary and permanent migration), involving a stay of more than three and twelve months, respectively. The inherently limited nature of the available statistical indicators on irregular migration ows do not easily allow one to make such a distinction in regard to irregular migration ows. It is sufcient to note that most analyses of irregular migration ows tend to interpret irregular border crossing as synonymous with an (irregular) migration event, without much consideration of the temporal dimension of migration and thus, without much consideration of the impact of recorded or estimated irregular migration ows on the stocks of irregular residents. Given the data limitations, it is nearly impossible to draw conclusions on the impact of irregular migration ows on the stocks of irregular migrants, not least since an unclear share of irregular entrants also submit asylum applications and thus do not become part of the irregular migrant stock or do so only considerably later. Indeed, status-related ows such as overstaying and negative asylum decisions are a major source of irregular migration ows. To assess the overall impact of ows on stocks, good estimates on all three components of irregular population and migration ows would have to be made. However, so far there have been no systematic attempts to account for the demographic balance of irregular migration by taking into account all types of ows into and out of irregularity, and the few available analyses largely focus on migration ows. Generally, estimates on irregular migration ows are few and far between. Indeed, most analyses of irregular migration ows limit themselves to analysing selected statistical indicators on (geographical) irregular migration ows, such as border apprehensions or refusals at the border. In addition to the more descriptive reports from government agencies, European Union institutions and

2011 The Authors. International Migration 2011 IOM

104

Kraler and Reichel

other international agencies, there are a number of more analytical studies of (geographical) irregular migration ows from Africa into southern Europe (Simon, 2006; de Haas, 2007; Carling, 2007b) and of irregular migration ows in Eastern Europe (Jandl, 2007). While Carling and Jandl essentially use available statistical indicators to indicate broad trends in the development and patterns of irregular migration, de Haas and Simon also attempt a global quantication of irregular migration ows. However, only de Haas provides a clear methodology for his estimate. The rst attempts to systematically collect statistical indicators on irregular migration in Europe go back to the early 1990s, when the perception of a looming immigration crisis, characterized by a major rise in the numbers of asylum applications and recorded irregular entries, contributed to more intensive international forms of cooperation on irregular migration, including the exchange of data regarding it. Thus, the exchange of information on asylum and irregular migration was one of the early key priorities of the International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD) in Vienna, whose then Director General Jonas Widgren produced the most widely known estimates on irregular migration ows to Western Europe, referred to in the introduction to this article. These in turn are based on apprehension statistics collected by ICMPD (see ICMPD, 1994; Widgren, 1994). In 1998, ICMPD began collecting a broad range of statistical indicators on irregular migration in central and Eastern Europe, and published them from 2001 onwards in its statistical yearbooks. At the European Union level, the Centre for Information, Discussion and Exchange on the Crossing of Frontiers and Immigration (CIREFI), established in 1992, began informally exchanging statistical data on irregular migration in the mid-1990s. Since 1998, Eurostat has been formally involved in the CIREFI data collection and has been collecting monthly data from that year onwards (Singleton, 2003). With the Commissions Annual Reports on Migration and Asylum the rst edition of which was launched in 2003 (with 2001 as a reference year) a large part of the annual data collected by CIREFI also became publicly available. Lack of publicly available information on denitions and sources of the respective national data compiled in the CIREFI data, however, leaves the CIREFI data collection a problematic source (see also Jandl and Kraler, 2006). Following the adoption of the force of the Regulation on Community Statistics on Migration and International Protection (Regulation No. 862 2007), data collection on apprehensions and return was put on completely new footing and is now collected and disseminated by Eurostat as Enforcement of Immigration Legislation (EIL) Statistics. EU member states are now legally obliged to provide statistical data on irregular migration on an annual basis. In addition, EIL statistics are, in contrast to CIREFI data, also systematically disseminated and published. However, statistical data on border apprehensions at the European Unions external borders are also compiled by the European Unions border agency, Frontex, in the framework of the Frontex Risk Analysis Network (FRAN). These data are not systematically published. Generally, statistical indicators of irregular migration have now increasingly become available for the European Union as a whole. The expansion of the

2011 The Authors. International Migration 2011 IOM

Measuring irregular migration and population ows

105

available data, however, has so far not been translated into increased efforts to analyse the available data more systematically. There is also a lack of understanding regarding current data collection, induced by the reluctance of authorities, at both the national and the supranational level, to make meta-documentation and more detailed statistics available. For this reason, most researchers tend to use national data and restrict their analysis to selected national case studies and multi-country analyses based on national data. Methods to estimate irregular migration and population ows In the last few years, increasing efforts have been made to produce scientically sound estimates of the irregular migrant population, notably in the United States, but also in an increasing number of European countries (see the Clandestino database at http://www.irregular-migration.hwwi.net/ and Iglicka, 2008) using a large variety of methods (Jandl, 2008; see also Jandl, this volume). In contrast, there have been fewer attempts to estimate irregular migration and population ows. In contrast to the broad range of methods available for estimating migrant stocks, the number of methods available in order to quantify irregular migration ows is extremely limited. Jandl (2008) identies three basic types of methods for estimating irregular migration ows: (1) estimates of net irregular ows based on a comparison of stocks of irregular migrants in different points in time, (2) estimates of irregular border crossings based on a multiplier estimate, and (3) estimates of overstaying based on comparisons of entry and exit records. In addition, two additional methods can be distinguished: (4) estimates based on information drawn from sample surveys of immigrants and (5) estimates based on comparisons of different data sources for geographical migration ows. Type (1) and (4) potentially cover all types of irregular population and migration ows, whereas type (2) and (5) estimates are specic to irregular migration ows and type (3) provides an estimation method for estimating a particular type of status related inow. (1) Net irregular population and migration ows can be calculated on the basis of stock estimates of the irregular migrant population for different years. Estimates of irregular net population and migration ows, by definition, only provide estimates on the total increase or decrease of the irregular migrant population and thus, do not distinguish between different components of irregular population and migration ows. Estimating net irregular population and migration on the basis of annual stock estimates is common practice in the United States, where annual stock estimates on the total irregular migrant population are readily available from the Pew Hispanic Centre (see, for example, Passel and Cohn, 2008) and the Department of Homeland Security (see Hoefer et al., 2009). In Europe, stock-based estimates of irregular population and migration ows have rarely been attempted, essentially because of the

2011 The Authors. International Migration 2011 IOM

106

Kraler and Reichel

lack of periodical stock estimates that would allow producing them. Only in Spain, where irregular migrants are registered in municipal population registers (Padron) and comparisons of residents in the Padron to the stocks of permit holders allow estimations of irregular migrant stocks, have stock-based estimates of irregular inows been undertaken.6 Partly based on estimates of the net change of the irregular migrant population in Spain, Hein de Haas has recently put forward an estimate of net irregular population and migration ows from West Africa to Spain. Assuming that Spains share of the irregular migrant population from West Africa is similar to Spains share of the total population of West African origin in Europe (20%), de Haas then estimates total irregular net migration from West Africa to Europe at 75,000. Using data drawn from a survey on Ghanaian and Senegalese migrants in Italy and Spain, which suggests that about one-third of surveyed immigrants entered the country irregularly (compared to two thirds of overstayers), de Haas estimates the annual number of successful irregular border crossings of West Africans to Europe at about 25,000 (Jandl, 2008: 55; De Haas, 2007: 46). Although based on an initial estimate of net irregular population and migration ows in Spain, the estimate of de Haas goes considerably beyond estimating net population change and combines different approaches in order to arrive at an estimate of overall irregular net migration from West Africa to Europe as well as the total number of irregular entries into Europe. The new Clandestino stock estimates of the irregular foreign resident population in the EU15 for 2002, 2005 and 2008 (see Vogel and Kovacheva, this issue) also allow an estimation of net irregular migration and population ows on the European level. According to the estimate, the total irregular resident population decreased between 1.3 and 2.1 million between 2002 and 2008. Annual net decrease thus averaged 0.22 million in the minimum and 0.33 million in the maximum variant. Regularisations and the impact of enlargement are the most likely factors contributing to the decrease (see also below). (2) A second approach to estimating irregular population and irregular ows specic to irregular migration are multiplier estimates, based on the numbers of apprehensions of irregular border crossings and an assumed ratio of apprehensions to non-detected successful border crossings. Multiplier estimates have been put forward by Heckmann and Wunderlich (2001: 64), who use a multiplier of two, and Widgren (1994), who assumed that the number of persons successfully entering Western European states was four to six times higher than the number of actual apprehensions. In later estimates, Widgren also used a multiplier of two, although he applied it to adjusted apprehension gures (Jandl, 2003). In all cases, the multiplier used is highly questionable. Heckmann and Wunderlich (2001) neither provide a source for their multiplier, nor do they justify its application to the phenomenon at hand (nor does Widgren justify his use of the multiplier of two). Presumably both Widgrens

2011 The Authors. International Migration 2011 IOM

Measuring irregular migration and population ows

107

later estimate and the estimate by Heckmann and Wunderlich are based on a multiplier taken from an inuential study of border apprehensions and apprehension rates at the US-Mexican border (Espenshade, 1995). Given that apprehension rates are highly sensitive to geographical factors (such as the nature of the border), border-policing practices as well as migrant behaviour, this multiplier is likely to be highly specic for the US-Mexican border at the time of the study, and there is little reason for applying the same multiplier to Europe. Widgrens earlier multiplier estimate, on the other hand, is based on subjective assessments by border guards, which he collected in a partial, unsystematic manner. Even if border guards were systematically surveyed, it is doubtful whether a reliable multiplier could be derived from such an exercise. Generally, the method used by Espenshade to arrive at a reasonable multiplier a direct survey of irregular migrants seems more appropriate for providing a reliable multiplier. In this context, however, of the close linkage of asylum and irregular migration in Europe and the great heterogeneity of irregular migrants in terms of countries of origin, reasons for migration, etc., it is likely that there will be greatly varying apprehension rates for different nationalities (and for different times). Thus, for certain categories of asylum seekers who have an interest in getting apprehended, the multiplier may be equal to one (for example, Chechen refugees in Austria; see Kraler et al., 2008: 30), while for other categories of migrants, much lower rates of apprehension will apply (see Jandl, 2004a: 151f). In addition, factors such as ethnic proling and other biases in policing also inuence apprehension rates. (3) The third method identied by Jandl is specically designed to estimate the number of over-stayers and is based on a systematic cross-check of entry and exit records. Evidently, this method would require a comprehensive entry and exit record system, based on registration of actual entries and exits. This not only requires specic technologies to register each border crossing,7 but also is premised on systematic de-registration at exit, which is much less often the case than registration at entry. It is not surprising then that this method has been most successfully applied in countries whose geography facilitates a systematic monitoring of entries and exits, such as Australia (see Department of Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs, 2005). In countries with long stretches of land borders and relatively large volumes of border trafc, the method seems to provide much less robust results. Thus, the high numbers of over-stayers suggested by cross-checks of entry and exist records in South Africa is likely to reect a large numbers of unrecorded returns to neighbouring countries rather than overstaying (see Wa Kabwe-Segatti and Landau, 2006: 163). In Europe, the method has so far not been applied, mostly because there are no comparable records on foreigners entering or leaving individual European countries. However, there are currently plans to implement a comprehensive

2011 The Authors. International Migration 2011 IOM

108

Kraler and Reichel

entry-exit record system for third-country nationals subject to a visa obligation at the European level (see European Commission, 2008a). If implemented, the system would provide data on entries into and exits from the European Union. Yet, to what extent such a system is going to provide reliable statistical information remains to be seen. Given the high numbers of border crossings (as compared to migration movements in the narrow sense), discrepancies between long-term entries and exits are likely to be of such a small magnitude that it will be hard to distinguish statistical errors and coverage problems from actual overstaying. (4) Indicators on migration movements drawn from sample surveys could in principle provide an interesting alternative method for estimating irregular population and migration ows. In practice, however, indicators of migration movements drawn from surveys are of limited use as a method for globally quantifying irregular migration ows and migra dena, 2007 on tion ows more generally (see for example Mart and Ro the use of the Labour Force Survey to estimate migration). Similar limitations apply to status related ows and vital events or demographic ows. Inherent limitations of survey based methods include: the problems of accurately sampling (irregular) migrants; issues concerning the extrapolation of information on migration trajectories drawn from the survey to migrants as a whole (i.e. questions of identifying suitable reference populations); the problem that reported movements are spread out over several years, and, if only recent movements are recorded, they usually concern only a relatively small share of migrants; and nally, inherent problems relating to the fact that sample surveys of resident migrants only provide information on migrants still residing in the country at the time of the survey and that surveys thus do not capture migration movements of those who have left the country before the survey was undertaken. However, despite these limitations, variables related to irregular entry are useful sources of information with respect to the relative quantitative importance of different pathways into irregularity, including the proportion of over-stayers ` -vis irregular entrants or the share of migrants entering with vis-a forged documents.8 (5) An additional potential method is to compare different data sources for (geographical) migration movements, also known as the residual method (see Jandl, this issue). For example, this method compares statistics on immigration based on population register data with data on residence permits issued in a given period, which is in principle possible in countries such as the Netherlands, the Nordic countries or Austria. In practice, however, differences between data sources often simply reect differences in the coverage and the design of the datasets, rather than irregular entries, and thus are difcult to use. Nevertheless, in countries with highly developed register systems such an approach seems to be a possible way forward.

2011 The Authors. International Migration 2011 IOM

Measuring irregular migration and population ows

109

DATA SOURCES ON IRREGULAR INFLOWS AND OUTFLOWS

As has been shown so far, analyses of irregular population and migration ows largely draw on apprehension statistics and, as a corollary, generally focus on irregular migration ows in particular, inows. Yet, there is more data available than apprehension statistics, including statistics on other types of ows. Potential data sources and indicators of irregular migration will be reviewed in the following section, below. Statistical Indicators on Irregular Migration Flows Inow indicators Apprehension statistics are the most frequently used source of data on irregular migration ows. Ideally, only border apprehensions should be used as an indicator of irregular migration ows. In practice, however, it is relatively difcult to make a clear distinction between border and inland apprehensions and hence between migrants entering or transiting a country and migrants who have been resident for some time and thus cannot be related to a recent, irregular migration ow. On the European level, the CIREFI data collection and the EIL data collection explicitly include both border and inland apprehensions (see Singleton, 2003). Statistics collected under the EIL data collection distinguish between refusals at the border dened as the number of third-country nationals formally refused permission to enter at the Schengen border and third-country nationals found to be illegally present according to the national law. In 2009, 570,660 third-country nationals were found to be illegally present in the EU-27 according to EIL statistics (Eurostat). CIREFI statistics indicate similar numbers for earlier periods, except for 2000 and 2001, when the numbers of apprehended migrants almost reached 700,000. Asylum applications are frequently taken as additional indicators of irregular migration ows. Indeed, asylum has become increasingly important as a route of entry into the European Union, as other admission channels have become closed, and both internal and external migration controls have massively stepped up in the course of the 1990s. However, while asylum seekers largely enter European countries in an irregular manner, and a signicant share of asylum applications is subsequently refused, asylum applications are also a problematic indicator of irregular migration ows as the outcome of the procedure whether asylum seekers are granted asylum and hence a legal status or not can only be established ex post and, in the absence of cohort data on asylum and subsequent enforcement, cannot be systematically established at all. In addition, failed asylum seekers may never be formally irregularly staying, for example, when removal immediately follows the refusal of an application or when persons who cannot be removed receive a toleration status. Thus, while asylum applications may indeed present a reasonable ow indicator for irregular forms of border crossings, the relationship to irregular migrant stock is entirely unclear.

2011 The Authors. International Migration 2011 IOM

110

Kraler and Reichel

Statistics on refusals at the border are often used as an additional indicator of irregular migration ows. However, as their relationship to irregular entries is unclear, they are less useful as a ow indicator. Outow indicators For outows, there are basically three types of data: (1) statistics on persons apprehended while leaving, (2) statistics on voluntary exits of persons obliged to leave the country, and (3) data on deportations. Data on aliens apprehended while leaving are likely to be patchy, may capture a large number of transit migrants and are highly sensitive to specic enforcement actions.9 In general, return statistics provide a much better data source, even though data on voluntary exits are never comprehensive since not all persons who leave the country voluntarily register their departure. Within the CIREFI data collection, and the EIL data collection replacing it, voluntary and forced returns are merged into one category (removed aliens). In addition, CIREFI EIL data also include an additional category (return decisions), which is used to calculate effective return rates. According to CIREFI data, some 797,700 persons were removed between 2004 and 2007 (as compared to 1.8 million apprehensions in the same period). The effective return rate was around 48 per cent in 2004 and dropped if Greece, which does not issue return decisions, is not considered to around 34 per cent (European Commission, 2009: 32 34). In 2009, the EU member states reported some 250,000 removals, with 50 per cent of all returns being reported by Greece and the United Kingdom alone. Statistical Indicators on Status-Related Flows Inow indicators Status-related ows are of major quantitative importance with respect to irregular migration. Among these, overstaying can be considered one of the main sources of ows into irregularity in a variety of countries. Thus, in Italy it is estimated that about 70 per cent of the undocumented population have entered the country legally with a valid visa (Fasani, 2008: 60), while the share of over-stayers in Spain seems to be of a similar quantitative importance. For many other countries, the proportion of over-stayers, however, is entirely unclear, even though it is generally assumed to be of a signicant scope. Quoting selected assessments of the share of over-stayers, a European Commission Memo from 2008 estimates that over-stayers may account for 50 per cent of irregular inows (European Commission, 2008b). In the European `context, surveys including information on the proportion of over-stayers vis-a vis legal entrants are currently the only available data sources on overstaying. However, there are a number of indicators on other types of status-related inows, in particular, for status-related ows linked to the asylum system.

2011 The Authors. International Migration 2011 IOM

Measuring irregular migration and population ows

111

Status-related ows in the context of the asylum system concern (1) asylum seekers who abscond during the asylum procedure and who subsequently often seem to migrate onwards to other European member states and (2) failed asylum seekers who remain in a European country, thus potentially contributing to the stock of irregular residents. Statistics on the former are mainly available as statistics on discontinued procedures a category which does not distinguish between different reasons for discontinuation. In addition, some countries collect specic data on rejected asylum seekers who have absconded. Outow indicators At rst glance, statistical indicators on status-related outows seem to be much more straightforward. Statistical data on regularisation programmes one major mechanism of transition from an irregular to a regular status are readily available in countries that have implemented regularisation programmes. However, in practice, there are also considerable gaps. Thus, data on both applications and regularisations granted are not always available, and it is often unclear how gures for two-stage regularisation procedures (such as the 1998 regularisation programme in Greece or the repeated programmes for tolerated persons in Germany) should be interpreted. In addition, there is a lack of systematic statistical data on ongoing regularisation mechanisms. Nevertheless, available data permit one to undertake a rough assessment of the overall scope of regularisation programmes. Thus, a recent survey of regularisation measures in the European Union (Baldwin-Edwards and Kraler, 2009) shows that between 1996 and 2007 about 4.2 million persons applied for altogether 42 programmes in 17 EU member states, during the course of which some 2.9 million persons were regularised. With respect to ongoing regularisation mechanisms, the study documents 300,000 grants of statuses since about 2001 (BaldwinEdwards and Kraler, 2009). For status transitions other than formal regularisation programmes such as the informal acquisition of a legal status in breach of formal requirements (e.g. an application from abroad), regularisation on account of marriage or regularisation as a consequence of EU enlargement statistical indicators are much scarcer. In the case of Italy, it is estimated that around 30 per cent of immigrants who were residing in the country irregularly applied for work permits under Italys quota system, pretending not to stay in the country (Fasani, 2008: 3537). For the United Kingdom, Anderson et al. (2006) have estimated that some 30 per cent of citizens of EU-8 countries registering for the workers registration scheme after enlargement in May 2004 had been staying in the United Kingdom in an irregular situation prior to registration (Anderson et al., 2006). In addition, ling an asylum application after a certain time of irregular residence in a country in principle also constitutes a status related ow according to our framework. However, while there is no clear evidence, it seems that the majority of asylum seekers actually lodge an asylum claim

2011 The Authors. International Migration 2011 IOM

112

Kraler and Reichel

relatively soon after arrival and certainly within a year if we take the time criterion suggested by the UN migration recommendations as a benchmark (cf. UN, 1998). Demographic Flows (Vital events) Inow indicators Statistical indicators on births to migrant parents in an irregular situation are extremely patchy, and no European country systematically collects data on the legal status of either newborn babies parents or on the legal status of the child. In some countries, data is available from healthcare centres and NGOs providing pre- and post-natal healthcare to irregular migrant parents (see, for the Netherlands, van der Leun and Ilies, 2008). Outow indicators As in the case of birth, no systematic data on deaths of persons without status are available. Statistics on deaths of irregular migrants en route to Europe are on the whole much more systematically collected, as migrant fatalities can be interpreted as a direct consequence of increased border controls and are, thus, a critical indicator of the negative consequences of European Union border management policies on irregular migrants (see Carling, 2007a). As our account of the demographic balance of irregular migration focuses on in- and outows to countries of immigration, however, statistics on migrant fatalities do not directly concern us here. Use and Limits of Statistical Indicators on Irregular Population and Migration Flows In the preceding sections, we have shown that there is a broad variety of statistical indicators on different components of irregular population and migration ows. Given the signicant gaps in available indicators and the uncertainty of many of these indicators, a comprehensive account of irregular population and migration ows is unrealistic. However, through a triangulation of different types of data, a fuller understanding of individual components of irregular population and migration ows contributing to the change of the irregular resident population seems feasible. In addition, a better understanding of the individual components of irregular population and migration ows is also important in its own right, notably to assess the impact and implementation of policies regarding irregular migration and understand the quantitative impact of individual pathways into and out of irregularity. Much more, however, needs to be done. In particular, we have neither survey-based data, which would allow us to investigate the relative importance of individual components of irregular population and migration ows, nor robust stock estimates, which would allow us to

2011 The Authors. International Migration 2011 IOM

Measuring irregular migration and population ows

113

estimate net ows. We also lack more detailed information on a variety of statistical indicators collected on irregular migrants, such as the share of apprehended persons lodging asylum applications, the share having done so in the past, or the reasons for a return decision (e.g., negative asylum decision, criminal offense, unlawful stay, etc.). The comparison of different in- and outow indicators also raises new questions. Thus, comparing the net decrease of the irregular migrant population in the European Union of between 1.3 and 2 million between 2002 and 2008 as suggested by the Clandestino stock estimates (Vogel and Kovacheva, this issue) to other ow indicators, notably the number of regularised persons (some 1.9 million persons were regularised between 2002 and 2008, see Kraler, 2009: statistical annex), not only suggests a signicant impact of large-scale regularisation programmes conducted over this period on the size of the irregular migrant population. But it also raises questions regarding the possible magnitude of inows into the EU, if the major part of the decrease of the irregular foreign resident population could be explained by regularisations alone. However, regularisation does not always represent an outow from irregular migrant stocks. Thus, regularisations often include persons with some form of recognised status and do not just involve persons in an irregular situation sensu stricto, if, for example, tolerated persons (such as in Germany) or long-term asylum seekers are covered by regularisation measures. The same holds true in regard to the more than 2 million persons who were removed from the present EU-27 between 2002 and 2008,10 many of whom were presumably not entirely in an irregular situation but found themselves in different types of quasi-statuses following, for example, a negative asylum decision or a temporary suspension of removal before being effectively removed. Conversely, the non-enforcement of return decisions which one could expect to be a major source of the irregular migrant stocks may not necessarily involve transitions to irregularity, when states systematically provide for a quasi-legal status for persons whose removal is temporarily suspended or when states operate under the legal ction that any previous legal status a person has held continues to be valid until the effective removal from the territory. While an analysis of individual components of irregular population may not in itself be a sufcient basis to estimate irregular population and migration ows, it helps to understand the quality and nature of available indicators and estimates and raises a number of important questions regarding policies on irregular migration that affect the size of the irregular migrant population. As our analysis suggests, however, the link between various irregular ows and irregular migrant stock may not be straightforward in the current context, in which patterns of irregular migration are characterized by a complex mix of movements into and out of irregularity. Nevertheless, as we will show in the following case study of irregular migration ows into the EU along its central and eastern borders, this does not mean that we cannot use available indicators for an analysis of trends. As we will argue below, if carefully delimited, an analysis of selected indicators of irregular population and migration trends can indeed provide important insights and highlight important trends. However, as we

2011 The Authors. International Migration 2011 IOM

114

Kraler and Reichel

would argue on the basis of our previous discussion of the individual components and complexity of irregular population and migration ows, we should be careful to interpret irregular migration ows the focus of the case study below as ows contributing to the irregular resident population. In Northern European countries, in particular, irregular inows are likely to contribute to the stock of asylum seekers, rather than the stock of irregular residents although this is likely to differ signicantly by citizenship and by country. In any case, only a detailed analysis of the links between asylum and irregular migration (i.e., through an investigation of the link of apprehensions at the border and asylum applications) would be able to show the extent to which irregular migration ows actually contribute to irregular migrant stocks.11 Sufce it to say that the uncertainty regarding the relationship between irregular forms of movement into the European Union and irregular migrant stocks reects its specic structure for global mobility. This unique structure affords few legal opportunities for mobility,12 but at the same time, also protects the rights of those with legitimate claims to international protection.

CASE STUDY: TRENDS IN IRREGULAR MIGRATION FLOWS TO EASTERN EUROPE AN ISSUE OF DECREASING IMPORTANCE?

The following case study of irregular migration ows to Eastern Europe attempts to show how a carefully delimited analysis allows one to make statements regarding overall trends in patterns of irregular migration. As our conceptual analysis in the above suggests, however, we should be careful not to confuse the irregularity of movement with subsequent irregular stay. This analysis is based on statistics of border apprehension at external EU borders collected by the International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD) from central and eastern European countries. This regional focus has been chosen for several reasons. The rst reason is pragmatic: detailed apprehension statistics, which distinguish between different border sections, between border and inland apprehensions and between apprehensions at entry and at exit, are readily available for all countries of this region. Second, the recent waves of enlargement have shifted the European Unions external borders further east. As a result of enlargement, many former irregular migrants to the EU-15 have become regular, changing the patterns of irregular migration (see Jandl, 2007). Because all of the countries included in our analysis border on non-EU countries, the data allows for an analysis of patterns of irregular migration at current (eastern) EU-borders. Indeed, in many ways, Europe as a whole seems now to be the more appropriate region for analysing irregular migration because: (1) the border controls in the European Union largely focused on the European Unions external borders and internal controls have changed signicantly, and (2) the irregular movements within the European Union include a sizeable share of secondary movements, which do not affect the overall stocks of irregular migrants in the EU. Focusing on irregular migration ows at the European Unions

2011 The Authors. International Migration 2011 IOM

Measuring irregular migration and population ows

115

external borders makes analysis, in many ways, easier, as internal movements can be neglected. In the following, we compare apprehensions at external EU borders to the overall number of apprehensions and identify the countries most affected by irregular border crossings in the past years. For our analysis of trends and developments of irregular migration ows into the EU, we disaggregate the data by border section as well as by direction of ows (see Table 1). Focusing on the irregular border crossings of EU external borders, we exclude irregular migration ows within the European Union. The differentiation by direction of ow allows us to exclude the substantial numbers of outbound ows recorded in these countries. The analysis includes data from Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia, all countries with external EU borders. The data include apprehensions of non-citizens as well as citizens of the reporting countries. The exact denition of apprehension for an unauthorised border crossing varies between countries. Some countries count their own nationals under irregular border crossings, others not. Differences are less pronounced if the nationals of reporting countries are excluded from the analysis.13 Data are not entirely

TABLE 1 TOTAL NUMBER OF MIGRATION-RELATED BORDER APPREHENSIONS (A), APPREHENSIONS AT CURRENT EXTERNAL EU BORDERS (B) AND APPREHENSIONS OF INFLOWS AT EXTERNAL BORDERS (C) IN BULGARIA, POLAND, HUNGARY, ROMANIA, SLOVAKIA AND SLOVENIA 2003 TO 2007 2003 (A) Poland Hungary Slovakia Slovenia Bulgaria Romania Total 5063 12990 12493 5018 5133 2133 42830 (B) 933 1973 5483 3520 2279 902 15090 2006 (A) Poland Hungary Slovakia Slovenia Bulgaria Romania Total 2741 16290 4129 3992 5518 1268 33938 (B) 1136 3096 2319 3129 2407 584 12671 (C) 902 1908 2308 1880 392 7390 (A) 2143 8779 3405 2479 2475 1421 20702 (C) 860 1480 5468 1430 601 9839 (A) 6012 13103 8334 5680 5948 1496 40573 2004 (B) 910 1311 3352 4332 2494 521 12920 2007 (B) 986 3387 1684 1913 1352 633 9955 (C) 700 1665 1674 1245 580 5864 (A) 19190 69456 33539 23087 24609 8452 178333 (C) 833 850 3352 1811 299 7145 (A) 3231 18294 5178 5918 5535 2134 40290 2005 (B) 991 2708 2586 4669 2195 699 13848 Total ( B) 4956 12475 15424 17563 10727 3339 64484 (C) 4156 7431 15356 7992 2184 37119 (C) 861 1528 2554 1626 312 6881

Source: Futo and Jandl, 20042007 and Futo, 2008, own calculations.

2011 The Authors. International Migration 2011 IOM

116

Kraler and Reichel

consistent over the years, presumably reecting ex post data adjustments. In case of differences between data, data from the most recent edition of the yearbook were taken. Figures on apprehensions at airports and at sea borders have been excluded, where possible. The total numbers of migration-related apprehensions at borders in central and eastern European countries have decreased steadily in the past years and more than halved between 2003 and 2007, from 42,800 apprehensions in 2003 to 20,700 in 2007. Out of more than 178,000 apprehensions in the six countries during the ve years of observation, most apprehensions (roughly 39%) were reported in Hungary. The second largest number of apprehensions was reported in Slovakia (about 19%), followed by Bulgaria, Slovenia and Poland (11 to 14%). The lowest number of apprehensions was reported for Romania (4.7%). These gures represent the total number of border crossings, including data on apprehensions at countries borders with other EU Member States and data on countries external borders as well as both in- and outows. To assess trends in geographic irregular migration ows into the EU more precisely, we present border apprehensions disaggregated by border section and direction of ows and then focus on inows at external EU borders or what became external EU borders during the course of the European Unions eastern enlargement. The external border sections of the countries included are shown in Table 2, below. Considering only apprehensions at current external EU borders, the numbers of apprehensions still decreased signicantly. Between 2003 and 2007, some 64,000 apprehensions at external borders of the current EU were recorded in the six countries. Hence, only 36.2 per cent, or roughly one-third, of all apprehensions were recorded at current external borders. Hungary recorded the largest share of apprehensions at external EU borders in 2007, but not in the entire period analysed here. Slightly more than a quarter of apprehensions were recorded in Slovenia at its border with Croatia, and roughly 24 per cent of apprehensions took place in Slovakia at its borders with the Ukraine. Some 12,000 apprehensions (19.3% of the total) were reported in Hungary and some 10,700 (16.6% of the total) in Bulgaria. Comparably few apprehensions at

TABLE 2 EXTERNAL BORDER SECTIONS IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPEAN COUNTRIES Reporting country Poland Hungary Slovakia Slovenia Bulgaria Romania Non-EU bordering country Ukraine, Russia, Belarus Ukraine, Serbia, Croatia Ukraine Croatia Serbia, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Turkey Ukraine, Moldova, Serbia

2011 The Authors. International Migration 2011 IOM

Measuring irregular migration and population ows

117

current EU external borders occurred in Poland (around 5,000) and Romania (around 3,300) during the ve years under study. So far, we have only looked at the total number of apprehensions at external EU borders, including both irregular in- and outows in the reporting country. In what follows, we take into account only apprehensions of persons trying to enter the country from outside of the EU in order to approximate trends of irregular inows via external EU borders. Between 2003 and 2007, some 37,000 apprehensions of persons irregularly entering Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, Bulgaria, and Romania were reported. The data from Slovenia are not disaggregated by direction of ow and are, therefore, not included in the following analysis. Out of all apprehensions at current EU external borders, almost 80 per cent concern inows. However, the ratios between inows and outows of reported apprehensions differ between the countries (see Table 3 below). Apprehensions of irregularly entering persons at current external EU borders constituted only 23.9 per cent of all migration related border apprehensions in Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, Bulgaria and Romania between 2003 and 2007. In the ve countries under observation, out of the almost 47,000 apprehensions at external borders, 9,800, or 20.9 per cent, concerned outows. Taking Hungary as an example, it becomes clear that irregular migration ows are not solely directed towards western European EU member states but also towards new EU member states and towards countries outside the EU (see Table 4 below). Apprehensions in the ve central and eastern European (CEE) countries included in the analysis have considerably decreased from 2003 to 2007, falling from 38,000 to some 18,000, an approximately fty per cent decline (see Figure 3). Apprehensions at current external EU borders declined much less, decreasing from some 11,500 to roughly 8,000, or by 30 per cent. However, if only inows at

TABLE 3 RATIOS OF INFLOWS AND OUTFLOWS AND SHARE OF APPREHENSIONS AT EXTERNAL BORDERS IN TOTAL NUMBER OF APPREHENSIONS Share of apprehensions at external borders in total number of apprehensions Poland Hungary Slovakia Slovenia Bulgaria Romania Total 25.8% 18.0% 46.0% 76.1% 43.6% 39.5% 36.2% Share of inows at external borders on total number of border apprehensions* 21.7% 10.7% 45.8% n. a. 32.5% 25.8% 23.9%

Share of inows at external borders* 83.9% 59.6% 99.6% n. a. 74.5% 65.4% 79.1%

Note: * without Slovenia. Sources: Own calculations based on Futo and Jandl, 20042007 and Futo, 2008.

2011 The Authors. International Migration 2011 IOM

118

Kraler and Reichel

TABLE 4 APPREHENSIONS IN HUNGARY Apprehensions of persons trying to leave Hungary Border to Austria Ukraine Romania Other Total 2003 4251 272 1984 1238 7745 2004 4570 354 2313 389 7626 2005 4860 1056 5249 463 11628 2006 2966 995 5817 790 10568 2007 2102 1328 226 1232 4888 Total 18749 4005 15589 4112 42455

Apprehensions of persons trying to enter Hungary Border to Austria Ukraine Romania Other Total 2003 485 435 530 1287 2737 2004 377 475 406 482 1740 2005 385 1079 616 536 2616 2006 633 730 896 1747 4006 2007 510 674 888 1276 3348 Total 2390 3393 3336 5328 14447

Sources: Own calculations based on Futo and Jandl, 20042007 and Futo, 2008.

external EU borders are considered, the decrease is more pronounced, with a decline of 40 per cent from 9,800 to some 5,900 apprehensions. The main reason behind the overall decrease is the decrease of apprehensions at the SlovakianUkrainian border, by almost 70 per cent from around 5,500 in 2003 to some 1,700 in 2007 (see Table 1). However, taking into account the numbers of apprehensions reported by the Ukrainian authorities as well, the decrease in apprehensions was not as sharp, since apprehensions in Ukraine towards Slovakia have increased from 2003 to 2005 and decreased again in 2007. (see Table 5, below). To sum up, total numbers of apprehensions in CEE countries have decreased signicantly in the past years. At the external borders of the current EU member states, the inow apprehensions have decreased while the recorded outows remained quite stable, with only a slight decrease. Although overall most apprehensions were reported in Hungary, the most important sections for external border apprehensions were Croatia-Slovenia and Ukraine-Slovakia. But how do the trends in geographic irregular migration ows in Eastern Europe compare to broader European patterns of irregular migration ows? We cannot provide a full analysis of irregular migration ows to the European Union here and limit ourselves to selected ow indicators and the possible conclusions that can be drawn from the available data. Figure 4 (see p. 24 below) shows four standardised indicators for geographic irregular migration ows in the European Union. These indicators include statistics of apprehensions at external eastern EU borders from the preceding case study analysed in more detail, apprehensions at selected Southern European

2011 The Authors. International Migration 2011 IOM

Measuring irregular migration and population ows

119

FIGURE 3 TOTAL NUMBER OF MIGRATION-RELATED BORDER APPREHENSIONS, APPREHENSIONS AT CURRENT EXTERNAL EU BORDERS AND APPREHENSIONS OF INFLOWS AT EXTERNAL BORDERS IN BULGARIA, POLAND, HUNGARY, ROMANIA AND SLOVAKIA 2003 TO 2007

40000 35000 30000 25000 20000 15000 10000 5000 0 2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

Total border apprehensions Apprehensions of inflows at external borders

Apprehensions at external borders

Sources: Own presentation based on Futo and Jandl, 20042007 and Futo, 2008.

TABLE 5 NUMBERS OF APPREHENSIONS OF PERSONS TRYING TO LEAVE UKRAINE IN THE DIRECTION OF EU COUNTRIES Border to Poland Slovakia Hungary Romania Total 2003 611 1297 115 107 2130 2004 774 1522 66 13 2375 2005 708 3234 104 7 4053 2006 736 3269 160 19 4184 2007 417 2422 253 59 3151 Total 3246 11744 698 205 15893

Sources: Own presentation based on Futo and Jandl, 20042007 and Futo, 2008.

maritime borders, and total numbers of apprehensions based on CIREFI data and asylum applications. As we have shown, apprehensions at external EU borders in Eastern Europe have seen a signicant decline since 2003. Similarly, statistics on asylum applications and apprehensions show a slight downward trend. If the timeframe is extended to 2000, the decline of both apprehensions and asylum applications is

2011 The Authors. International Migration 2011 IOM

120

Kraler and Reichel

FIGURE 4 SELECTED INDICATORS OF IRREGULAR MIGRATION FLOWS INTO THE EUROPEAN UNION (STANDARDISED INDICATORS, 2003 = 100)

200 180 160 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007

Total Border Apprehensions at the EU's Southern Sea Borders Total Border Apprehensions at Current Eastern EU Borders Total aprehensions EU 25 Asylum EU 25

Sources: Data on Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, Slovania, Bulgaria, Romania: Futo and Jandl, 20042007; Futo, 2008. Data on Italy: Ministry of the Interior; on Greece: Maroukis, 2008; lez-Enon Spain 2003 to 2005: De Haas, 2007: (Appendix); on Spain 2006 and 2007: Gonza quez, 2008; on asylum applications: Eurostat database; on apprehensions (CIREFI data): r dap BIVS, 2005; European Migration Network, 2008; European Commission, 2009. Ge

even more pronounced. Both gures peaked in 2001 and sharply declined subsequently. Apprehensions in the EU-25 have declined from just under 692,000 in 2001 to around 460,000 in 2007, while the number of asylum applications has declined from 416,000 to about 220,000 (EMN, 2008; European Com DAP Berlin Institute for Comparative Social Research, 2005; mission, 2009; Ge UNHCR, 2009). Only apprehensions at southern European maritime borders seem to have greatly increased since 2003. However, if apprehension statistics at southern maritime borders are disaggregated by place of apprehension, it becomes clear that the overall increase of apprehensions at southern borders is entirely due to the short-lived increase of irregular entries at Italys southern shores between 2003 and 2005 and the signicant inows recorded at the Canary Islands in 2006, both of which can be interpreted as exceptional events. The overall trend, therefore, also seems to point towards a decrease of irregular entries at the EUs southern borders. A decrease in the overall volume of irregular migration ows seems also to be consistent with the Clandestino stock estimates for the irregular migrant population in the EU-25 for the years 2002, 2005 and 2008 (see Vogel and Kovacheva, this issue; see above). Enlargement has certainly reduced the pool of irregular migrants coming to the EU, as citizens of new EU member states notably Poles before 2004 and

2011 The Authors. International Migration 2011 IOM

Measuring irregular migration and population ows

121

Bulgarians and Romanians before 2007 were signicant categories of irregular migrants in some EU member states. While enlargement may have turned formerly irregularly staying citizens from new EU Member States into legal residents, their involvement in informal economic activities, by contrast, may not have changed. The increasing policing of the labour market combined with the more drastic sanctions faced by both employers and employees for the employment of illegally staying migrants from third countries may well mean that undocumented third-country nationals are increasingly pushed out of the labour market and or are further pushed down to even more precarious positions and forms of employment. Indeed, this is what some recent studies seem suggest (see, for example, the studies compiled in Bommes and Sciortino, 2011). Whether the marginalisation of irregular migrants on Europes labour markets has contributed to a decline in irregular entries, however, must remain an open question. Media images of migrants arriving at the European Unions southern maritime borders as well as statistics on apprehended boat people seem to tell a different story and suggest a rise of irregular migration. However, as we have shown, available indicators on overall trends do not support this conclusion. On the contrary, available evidence seems to suggest that the rise of apprehensions in southern Europe or more precisely, Italys southern shores and the Canary Islands should be interpreted as an exceptional phenomenon and not indicative of a trend.

CONCLUSIONS

This article has shown that there are multiple ways in which migrants become, or cease to be, irregular migrants. These can be interpreted as ows into and out of the irregular resident population and can be grouped into three types of ows: geographic or migration ows, demographic ows and status-related ows. There are a variety of potential indicators for each of these different types of ows, although most indicators refer to specic subtypes of the three main types of ows. Nevertheless, these indicators can be useful for assessing broad trends regarding the dynamics, patterns, as well as structure of irregular migration. Moreover, statistical indicators on different types of irregular migration are also important in their own right, notably for assessing state policies towards irregular migration, both in terms of effectiveness and of implications for irregular migration. In addition to statistical indicators of irregular migration ows, there are a limited number of methods that can be used to estimate the volume of irregular population and migration ows, both globally and for specic components of irregular population and migration ows. Finally, survey-based approaches allow for an assessment of the relative importance of different components of irregular migration ows, particularly the relative importance of status-related versus geographic inows (i.e., irregular migration). As we have argued in the above, however, we need to be careful in interpreting the link between different (potential) in- and outows on the one hand and irregular migrant stocks on the other.

2011 The Authors. International Migration 2011 IOM

122

Kraler and Reichel

Statistics of border apprehensions represent the most frequently used indicator for irregular migration ows. In the absence of plausible information on the rate of detected versus non-detected migrants, however, no conclusions on the overall volume of inbound geographic irregular migration ows can be drawn from apprehension statistics. Nevertheless, as our case study has sought to demonstrate, apprehension statistics can still serve as useful trend indicators. To be useful for the analysis, statistics need to be disaggregated by place of apprehension and direction of movement, which is not always the case and increasingly less possible in regard to apprehension within the Schengen zone. Limiting the analysis of apprehension statistics to apprehensions at the EUs external borders and using statistics on border apprehensions, as we have done, thus avoids some of the problems associated with the unclear nature of apprehension data. Our analysis of border apprehensions suggests that irregular migration ows at the European Unions eastern external borders have considerable declined between 2002 and 2007 (see also Jandl, 2007). In particular, this decline can be seen in Slovenia and Slovakia, the countries with the largest number of apprehensions at borders. Even though apprehensions are mostly reported in the direction to Western Europe, a sizeable number of migrants are apprehended while attempting to cross an external EU border towards non-EU countries, suggesting a signicant level of irregular return and circular migration. Given that all of the countries in the region have considerably stepped up their border controls, the decrease of reported border apprehensions suggests that inows have, in fact, considerably decreased. At the same time, some caution is warranted. As a result of enlargement and often preceding it citizens of new member states no longer need a visa to enter the older member states and, thus, are no longer subject to apprehensions at the (now internal) border, or are so at much lower extent. This decline may to some degree also reect a change in migrant strategies: the increased use, for example, of legal opportunities for movement and subsequent overstaying or the use of forged documents which remains under-researched as a phenomenon and, in the absence of any reliable data, must for now remain a mere hypothesis.

NOTES

1. Jonas Widgren later also became a source for the estimate of 500,000 irregular migrants, although it is not entirely clear when he rst began to circulate this estimate. He was rst cited as a source by Europol report in 1998 (see Jandl, 2003). According to Jandl, Widgens estimate is based on apprehension statistics, an assumed multiplier of 2 and the ratio of asylum seekers arriving irregularly in European countries. 2. The Centre for Information, Discussion and Exchange on the Crossing of Frontiers and Immigration (CIREFI) was set up in 1992 and since 1994, has a formal mandate to collect data on irregular migration, provided by member states on a voluntary basis. Since the launch of the Commissions Annual Statistical Report on Migration and Asylum, the larger part of the data collected by CIREFI on border apprehension has also become publicly available.

2011 The Authors. International Migration 2011 IOM

Measuring irregular migration and population ows

123