Professional Documents

Culture Documents

05 FJ10 Turner All

Uploaded by

nhandutiOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

05 FJ10 Turner All

Uploaded by

nhandutiCopyright:

Available Formats

Caption s by Introdu ction Photogr aphs

Veteran luthier R ick Turn emerge er s with h i s l atest cr the Com eation, pass Ro se acou stic guit a

Rick Tu rner by Mich ael John Simmon by Gran s t Grobe rg

NEEDL E

r

M OVING THE

YOU

Sanding the handcarved top braces.

only have to spend a few minutes at Rick Turners company to realize hes full of restless energy and blessed with an insatiable urge to Get Things Done. His passion for invention has made him one of the most notable electric-guitar innovators of the last 40 years. Turner co-founded Alembic Guitars in 1970, developed the acoustic/electric Renaissance Ampli-Coustic line of instruments and designed the Turner Model 1 best known as Lindsey Buckinghams main guitar. And, if thats not enough, he was president of Gibson Labs West Coast R&D Division in the late 1980s, where he worked with the guitar worlds greatest tinkerer, Les Paul. He also co-founded Highlander Musical Audio, worked on the Grateful Deads legendary Wall of Sound rig in the 1970s and partnered with Seymour Duncan to produce the D-TAR acoustic amplication system. A few years ago, Turner was approached by Barry Pearlman with a business opportunity. Pearlman had just started playing ukulele, and so the pair started making ukes under the Compass Rose name. And while doing all of that, Turner managed to repair and restore thousands of guitars over the years, for regular players as well as guys like Jackson Browne, Ry Cooder, David Lindley, David Crosby and Andy Summers. Since Turners a guy who knows how to get things done, its a bit surprising to nd that his latest project, the Compass Rose acoustic guitar, has been incubating for decades. I didnt want to start building acoustics until I felt I had enough ideas to bring to the table, he explains. Im not drawn to making yet another Martin. There are plenty of people making great Martins, including Martin. Turner spent years cogitating over the guitars that inspired him as well as the ones that disappointed him and developed a formula for his ideal guitar sound.

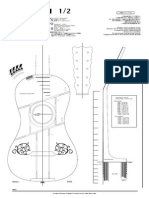

74 the fretboard journal

What I came up with was something that was maybe 75 [percent] to 80 percent attop, 15 percent archtop and then maybe a smidgeon of Maccaferri thrown in, he says. Ive worked with enough acoustic instruments to know that what can be very appealing about some guitars a huge bass, say, or tinkly trebles turns into a nightmare in the recording studio. I wanted to have something that would have that midrange punch and cut that you get with a great archtop or the Selmer-Maccaferri-style guitars, but have a little more attop-friendly bottom end underneath it. Once Turner had a sound in mind, he began to design his guitar, drawing on classic guitars of the past and melding their design elements with ultramodern materials like carbon ber. The body shape of the Compass Rose starts off with Orville Gibson, Turner says. Orville made a huge 18-inch guitar in this shape in the 1890s. Then the body shape was resuscitated in 34 with the rst small-shouldered version of the Super 400. Turner took that 18-inch silhouette and reduced it so his guitars measure a more manageable 15 or 16 inches across the lower bout. He also used a top-bracing pattern that melds the X pattern developed by Martin in the 1840s with the fan braces pioneered by Torres in the 1850s. Turners bridge design recalls the sort of thing that might have turned up on an 1820s Parisian guitar or maybe a Maurer from the 1930s. I like this little game of putting these little reminders of the past on my guitars, he says. People will look at stuff like my bridge and theyll say, Now where have I seen that before? The most unusual features of the Compass Rose are the neck attachment, which was inspired by the HoweOrme instruments of the early 1900s, and the ying buttress neck support. Ive worked on lots of vintage and antique guitars in my day, and Ive seen how a couple hundred years worth of guitars can fail, Turner says. More

The ying buttresses come down to the abutments in the waist and y up to the neck block. You can also see the reverse kerng, which was developed by Charles Fox, the side doubler and the kerng for the back. The buttresses relieve the top of the responsibility of supporting the neck and the ngerboard. I rst did this with some rebuilt guitars I did a few years ago. I did a Martin, a couple of Gibsons, a Guild when I was in Los Angeles. I think the rst one I did was for Jackson Browne. I tried the ying buttresses as a way of trying to separate the issue of engineering architecture from the issue of tone production. These do their job; the top no longer has to support the pressure of 160 to 180 pounds of neck bearing against it.

the fretboard journal 75

Matt Tolley cuts out sections of the back kerng (to let in the back bracing) as hes tting the back to the sides.

often than not, the neck-joint area fails in any number of ways. I wanted to come up with a system that offered maximum support without detracting from the sound, so I came up with a ying buttress that takes the tension from the neck and distributes it to the sides. I took my inspiration from the Gothic cathedral of St. Denis just outside of Paris. Its walls are supported by ying buttresses, which keep them from collapsing outward from the pressure of the roof. Hey, from 1183 to 2008 without falling down is a pretty good argument for the concept. The Compass Rose neck attachment is easily tiltable and has a cantilevered ngerboard, features that can be found on the rst Martins built in the 1830s, the guitars of Viennese builders like Stauffer and Schertzer and the guitars and mandolins made by Howe-Orme. The big deal is instant action adjustment, Turner says, but because the neck joint isnt doing the job of supporting the string tension, it allows us to have the end of the fretboard oat above the top without dampening the tone. One of the Compass Rose prototypes went through what was perhaps the toughest tryout any guitar ever had. In 2001, Henry Kaiser took his new guitar to Antarctica for two and a half months on a grant from the National Science Foundations Antarctic Artists and Writers Program. Kaiser reports that the guitar performed admirably under the extreme conditions. After hearing so much about the innovative Compass Rose guitars, we were curious and wanted to get a closer look at one, so we sent photographer Grant Groberg to visit Turners shop at various times during the construction of a single guitar. Turner had mentioned that his master luthier, Matthew Tolley, was about to start one with cocobolo sides and back and a very fancy bear claw spruce top. We were welcome to stop by as many times as we wanted; Groberg made half a dozen visits to Turners shop and came back with almost 1,500 images to sort through. Turner himself was kind enough to explain what was going on in each shot, and together we offer an unprecedented look at the construction of a unique guitar.

76 the fretboard journal

Milling a at section on the steel bar that gets welded to the truss rod and winds up in the heel of the neck.

above: A nice shot of the completed sound port. Side ports work as a personal monitor for the player. Our guitars tend to be very loud out front and tend not to be terribly loud to the player unless we put in a side port. Theyre designed, really, to project. We have control over the sound dispersion of guitars these days; we can choose to make them punch forward or really envelop the player. This particular series of guitars is designed to punch forward, so to give the player something, I love the side port. There are all kinds of jokes about it: Is it a beer holder, an ashtray or what? You can also see the pillars that reinforce the sides and go down to the back braces. This makes the whole back structure incredibly strong. On the rst one that I made with this general kind of internal construction, Henry Kaisers Antarctica guitar, I was able to ip the guitar upside down at this stage of development and literally stand on the center of the back.

78 the fretboard journal

Matt sands the end block with the guitar sides in the mold. Earlier, he put the spreaders into the sides at the upper and lower bouts and in the waist to clamp the sides into the mold. On the edge closest to Matt, you can see the side doubler of rosewood running around what will become the top joint.

The support block for the ying buttresses is glued in place. Hes putting in a cross-grain pillar that goes between the top and the back and is then glued to the waist. This is the support end of the carbon-ber rods that go up to the neck block.

left: This is a classic go bar shot. I dont know the history of go bars, but they are a really good idea. This is the same way they glue bracing on a grand piano. They have a go bar deck at Steinway, much larger than this, and it is an incredibly versatile system using the springiness of either wooden dowels or the modern equivalent berglass rods. The great thing about the go bar attach is that you can get anywhere between the two surfaces and youre not locked into a particular bracing pattern or anything like that. Its just a very, very versatile system. below: The back braces are being glued onto the back using go bars. The back braces are spruce with carbon-ber tops, and they are bridged over the center-seam reinforcement see the little gap? which also has a carbonber top. (The go bars are berglass and just happen to be black like the carbon ber.)

above: This is a set of the truss rods that we make, and you can see the 3 8" steel dowel that is welded into the rod that goes through the heel of the instrument to take the stress off the cross grain of the heel. left: Here, we are drilling out the tuner holes after the overlays have been glued to the face of the peghead. So this is sort of re-drilling: The peghead has a ve-layer laminate on the back, and theres the core of the peghead, and then theres a single overlay on the face, so these have to get drilled several times in the process of making them.

the fretboard journal 81

Matt ts the truss rod. I originally developed the headstock shape for the Model 1 electric guitar, and it just kind of became a signature. When I was working on peghead designs, I was getting all convoluted and baroque, and suddenly I said, Wouldnt it be nice if I could just do it with a ruler? And I basically did; I just went for the simplest possible thing that I could do. I like the A-line or snake peghead concept for straighter string pull; it makes nal setup easier and it helps keep the strings from binding in the nut.

82 the fretboard journal

Matt is hand-bending the binding that will go into the handstop curved area of the peghead. What you see here is the bending iron, which is a piece of brass pipe with a heating element inside, and a wet paper shop towel, which is providing the steam to help soften and bend the wood. This is going back to pretty primitive ways of doing things. Sometimes thats the easiest way.

Gluing on the back binding and puring. The binding on this guitar was plain maple. We use wood, plastic, ber and, in this latest guitar, even carbon ber for puring, which I really like. We pre-bend the binding in the same side-bender setup that we use for the sides, while the puring is exible enough to just bend in place.

Here, Matt is putting in the abalone shell inlay. The lines of puring have been put in with a sacricial piece of Teon in the middle, which gets glued in and then pulled out because the glue does not stick to the Teon, leaving a perfect channel for dropping in the pieces of abalone shell. Our cosmetic look doesnt really replicate the specic look of older guitars, but it is strongly reminiscent of earlier designs. If theres an overarching aesthetic that I strive for, its these little memory ticklers of guitars from the past.

the fretboard journal 83

This is me on the pin router shaping a bridge. I do at least something on 99.9 percent of the instruments that come out of here. At the very least, Ive sprayed the nish. In many cases, I do the more dangerous operations, like this, for instance. You can see my hands awfully close to the bit, which is going 20,000 r.p.m. I do a lot of these more dangerous processes myself cause Ive been doing it for years and I havent lost a nger yet.

The guitar is almost complete. Heres the nal tting of the tuners.

84 the fretboard journal

And bingo, the guitar is ready to play. Check out the bear claw gure in that top. The legend is that the gure came from bears scratching the trees, which is a wonderful story that just doesnt happen to be true. Its a genetic deformity of the wood that does affect the cross grain (versus long grain) stiffness of the wood. I think that it probably makes the wood stiffer and denser, so theres a tradeoff there, and you could theoretically work the plates a little thinner.

the fretboard journal 85

Isnt that cocobolo outrageous? It sounds great, too.

86 the fretboard journal

This is a nice silhouette showing the gaps between the ngerboard in the top and the face of the heel and the end of the guitar. You can see, just under the ngerboard, there are two screws, one on either side of the neck, which act as pivot points and are adjustable, so that the entire neck can be moved in and out to adjust overall intonation. The bolt in the middle is the one that actually sets the angle of the neck, and the one closer to the cap of the heel is a locking screw that locks the neck in place once its set.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- FF CP PentatonicDocument2 pagesFF CP Pentatoniczdravko mureticNo ratings yet

- Folk Harp Design and ConstructionDocument16 pagesFolk Harp Design and ConstructionnhandutiNo ratings yet

- The Harpsichord Its Timbre Its Tuning PRDocument2 pagesThe Harpsichord Its Timbre Its Tuning PRnhandutiNo ratings yet

- PGH Session TunebookDocument199 pagesPGH Session Tunebooknhanduti100% (1)

- Miter GaugeDocument8 pagesMiter GaugenhandutiNo ratings yet

- PGH Session TunebookDocument199 pagesPGH Session Tunebooknhanduti100% (1)

- Bridge TemplatesDocument5 pagesBridge TemplatesnhandutiNo ratings yet

- ASSARÉ, Patativa. Cordéis e Outros PoemasDocument118 pagesASSARÉ, Patativa. Cordéis e Outros PoemasPôlipìpô Salamandra100% (1)

- 1607 08610 PDFDocument9 pages1607 08610 PDFnhandutiNo ratings yet

- Rains of Castamere Full ScoreDocument3 pagesRains of Castamere Full ScorenhandutiNo ratings yet

- ASSARÉ, Patativa. Cordéis e Outros PoemasDocument118 pagesASSARÉ, Patativa. Cordéis e Outros PoemasPôlipìpô Salamandra100% (1)

- Dulcimer HourglassDocument2 pagesDulcimer HourglassnhandutiNo ratings yet

- Archtop Guitar ManualDocument123 pagesArchtop Guitar ManualCarlo351100% (13)

- Altoids Ukulele PlansDocument12 pagesAltoids Ukulele PlansSérgio Gomes Jordão100% (1)

- Typical Violin Sizes in Inches (MM)Document1 pageTypical Violin Sizes in Inches (MM)nhandutiNo ratings yet

- Angeline The BakerDocument2 pagesAngeline The BakernhandutiNo ratings yet

- Instrument Measurement List: Violin Body LengthsDocument2 pagesInstrument Measurement List: Violin Body LengthsnhandutiNo ratings yet

- 964,660, Patented July 19, 1910.: G. D. LaurianDocument6 pages964,660, Patented July 19, 1910.: G. D. LauriannhandutiNo ratings yet

- Wildwood Flower1Document2 pagesWildwood Flower1nhandutiNo ratings yet

- Freight TrainDocument1 pageFreight TrainnhandutiNo ratings yet

- Irish Bouzouki (Octave Mandolin) Kit: Musicmaker'S KitsDocument20 pagesIrish Bouzouki (Octave Mandolin) Kit: Musicmaker'S KitsnhandutiNo ratings yet

- Banjo DesignDocument1 pageBanjo DesignnhandutiNo ratings yet

- 996,652. Patented July 4, 1911.: G. D. LaurianDocument5 pages996,652. Patented July 4, 1911.: G. D. LauriannhandutiNo ratings yet

- The Last Steam Engine TrainDocument2 pagesThe Last Steam Engine TrainRonin011100% (1)

- Dulcimer HourglassDocument2 pagesDulcimer HourglassnhandutiNo ratings yet

- Pplleeaassee Ttaakkee Ttiim Mee Ttoo Rreeaadd Tthhiiss Wwaarrnniinngg!!Document8 pagesPplleeaassee Ttaakkee Ttiim Mee Ttoo Rreeaadd Tthhiiss Wwaarrnniinngg!!nhandutiNo ratings yet

- Genaro Fabricatore 1833 Guitar PlanDocument0 pagesGenaro Fabricatore 1833 Guitar PlannhandutiNo ratings yet

- AcusticoDocument4 pagesAcusticoJuli SatriaNo ratings yet

- CRANE Baroque GT A003!1!2Document1 pageCRANE Baroque GT A003!1!2Fran YborNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- M81 Bass Preamp: 92503016739revaDocument2 pagesM81 Bass Preamp: 92503016739revajepri purwantoNo ratings yet

- KORG N264 N364 Service ManualDocument14 pagesKORG N264 N364 Service Manualjfinnegan87No ratings yet

- Iraudamp 5Document51 pagesIraudamp 5Shaun Dwyer Van HeerdenNo ratings yet

- Cancao Do Mar (Cello)Document1 pageCancao Do Mar (Cello)Alberto CarrilloNo ratings yet

- SB21ChordCharts PDFDocument168 pagesSB21ChordCharts PDFDeris Rodríguez100% (1)

- Blessed Be God - Abner Ryan TauroDocument3 pagesBlessed Be God - Abner Ryan TauroReynald Ian CruzNo ratings yet

- Section # 4 A (RELATIONS, FUNCTIONS, GRAPHS I)Document15 pagesSection # 4 A (RELATIONS, FUNCTIONS, GRAPHS I)Anthony BensonNo ratings yet

- Music Speaks Studio PoliciesDocument4 pagesMusic Speaks Studio Policiesapi-289274685No ratings yet

- Augmented Sixth Chords: An Examination of The Pedagogical Methods Used by Three Harmony TextbooksDocument7 pagesAugmented Sixth Chords: An Examination of The Pedagogical Methods Used by Three Harmony TextbookshadaspeeryNo ratings yet

- Booklet. Samsom. Handel. 2020.Document66 pagesBooklet. Samsom. Handel. 2020.Emmanuel Pool KasteyanosNo ratings yet

- Paul Gilbert Intense Rock 1Document4 pagesPaul Gilbert Intense Rock 1Elvis Gonzalez-PerezNo ratings yet

- Risk of Sound-Induced Hearing Disorders For Audio Post Production Engineers: A Preliminary StudyDocument10 pagesRisk of Sound-Induced Hearing Disorders For Audio Post Production Engineers: A Preliminary StudylauraNo ratings yet

- Korean Traditional Music and CultureDocument7 pagesKorean Traditional Music and CulturePaulNo ratings yet

- Full Fathom FiveDocument5 pagesFull Fathom FiveRachel PerfectoNo ratings yet

- Informal Letters ExamplesDocument28 pagesInformal Letters ExamplesSean James ClydeNo ratings yet

- Biografi Bhs InggrisDocument9 pagesBiografi Bhs InggrisYuanda RisnadiputraNo ratings yet

- FOR NO ONE Cifra - The Beatles - CIFRASDocument2 pagesFOR NO ONE Cifra - The Beatles - CIFRASLevi AlvesNo ratings yet

- Merit ListDocument74 pagesMerit ListM Faisal DogarNo ratings yet

- Wiggins UbdDocument8 pagesWiggins Ubdapi-198345293No ratings yet

- Hijo de La Luna Loona TranscriptionDocument31 pagesHijo de La Luna Loona TranscriptionSinka MelindaNo ratings yet

- The Kodaly Method - Adele CummingsDocument4 pagesThe Kodaly Method - Adele Cummingsjp siaNo ratings yet

- Final Exam Questions #9 - SoundDocument5 pagesFinal Exam Questions #9 - Soundanonslu2012No ratings yet

- So Near, So Far: Kabul's Music in Exile: John BailyDocument21 pagesSo Near, So Far: Kabul's Music in Exile: John BailyerbariumNo ratings yet

- Lesson 5 - RhythmicDocument4 pagesLesson 5 - RhythmicBeatriz CincoNo ratings yet

- DAS Factor 5 SpecsDocument2 pagesDAS Factor 5 SpecsJeremy.S.BloomNo ratings yet

- Runaway Chord GuitarDocument4 pagesRunaway Chord GuitarDiana ApriliyaNo ratings yet

- EditingDocument28 pagesEditingAKSHAT0% (1)

- Marshall Plexi Super Lead 1959 ManualDocument29 pagesMarshall Plexi Super Lead 1959 Manualalbin21No ratings yet

- 2013 Gretsch CatalogDocument41 pages2013 Gretsch CatalogNick1962100% (2)

- Popstar Never Stop Never StoppingDocument78 pagesPopstar Never Stop Never StoppingSaraNo ratings yet