Professional Documents

Culture Documents

MANU/TN/0028/1983: Equivalent Citation: 1984 (15) ELT289 (Mad.) in The High Court of Madras

Uploaded by

Arvind RayOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

MANU/TN/0028/1983: Equivalent Citation: 1984 (15) ELT289 (Mad.) in The High Court of Madras

Uploaded by

Arvind RayCopyright:

Available Formats

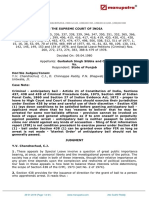

MANU/TN/0028/1983 Equivalent Citation: 1984(15)ELT289(Mad.) IN THE HIGH COURT OF MADRAS W.P. Nos.

5016, 5244, 6192, 6193 and 6800 of 1983 Decided On: 09.11.1983 Appellants: Roshan Beevi and Ors. Vs. Respondent: Joint Secretary to Government of Tamil Nadu and Ors. Hon'ble Judges/Coram: K.M. Natarajan, S.A. Kader and S. Ratnavel Pandian, JJ. Counsels: For Appellant/Petitioner/Plaintiff: M.R.M. Abdul Kareem, M.M. Abdul Razack, K.A. Jabbar, M. Abdul Nazeer, P.M. Jummakhan, P.M. Prem Nazirkhan, Rangavajjula Krishnamurthi and A.A. Lawrance, Advs. For Respondents/Defendant: Public Prosecutor Subject: Criminal Subject: Law of Evidence Catch Words Mentioned IN Acts/Rules/Orders: Constitution of India - Article 20(3), Constitution of India - Article 21, Constitution of India Article 22, Constitution of India - Article 22(2), Constitution of India - Article 226; Indian Penal Code 1860, (IPC) - Section 99, Indian Penal Code 1860, (IPC) - Section 193, Indian Penal Code 1860, (IPC) - Section 225, Indian Penal Code 1860, (IPC) - Section 228, Indian Penal Code 1860, (IPC) - Section 241, Indian Penal Code 1860, (IPC) - Section 339, Indian Penal Code 1860, (IPC) - Section 342; Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC) - Section 2, Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC) - Section 36(1), Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC) Section 43, Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC) - Section 45, Code of Criminal Procedure,

1973 (CrPC) - Section 45(1), Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC) - Section 46, Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC) - Section 160(1), Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC) Section 164, Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC) - Section 167(1), Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC) - Section 438, Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC) - Section 439; Indian Evidence Act - Section 24, Indian Evidence Act - Section 25, Indian Evidence Act Section 26, Indian Evidence Act - Section 27 Case Note:

Criminal - detention - Articles 20 (3), 21, 22, 22 (2) and 226 of Constitution of India, Sections 99, 193, 225, 228, 241, 339 and 342 of Indian Penal Code, 1860, Sections 2, 36 (1), 43, 45, 45 (1), 46, 160 (1), 438 and 439 of Criminal Procedure Code, 1973, Sections 24 to 27 of Indian Evidence Act and Section 104 (1) of Custom Act - whether detention of any person by Custom Official beyond 24 hours without producing him before Magistrate violative of Article 22 - Article 22 (2) requires arrester to produce arrestee before Magistrate within period of 24 hours excluding time necessary for journey from place of arrest to Magistrate - once person arrested either by Customs Officer under Section 104 (1) or by any other persons authorised Article 22 (2) would come into play and anything contrary to that would be violative of Article 22 (2) - held, Custom Officers when acting under Customs Act should see that procedural safeguards which are indispensable essence of liberty of citizen are not impaired in any manner.

JUDGMENT Ratnavel Pandian, J. 1. The above five writ petitions under Article 226 of the Constitution of India, have been filed challenging the legality and validity of the orders of detention in the respective cases, passed under Section 3(1) of the Conservation of Foreign Exchange and Prevention of Smuggling Activities Act, 1974 (hereinafter referred to as the COFEPOSA Act). 2. One of the main grounds raised in all these writ petitions on the strength of an observation made by a Division Bench of this Court, consisting of Balasubrahmanyan, J. and M. N. Moorthy, J. in Kaiser Otmar v. State of Tamil Nadu, 1981 MLW 158 : 1981 Cri LJ 208 is that the detenu should be deemed to have been arrested from the moment they were taken into custody by the Customs officials, even if it be under the guise of any enquiry or interrogation, and that their subsequent custody with the Customs Department without being produced before the Magistrate within 24 hours as envisaged in Article 22(2) of the Constitution of India, would amount to an illegal detention and any statement or statements recorded from those persons by the Customs officials during this prolonged period of custody should be held to have been made by the detenues not on their own volition or free will and hence such statements cannot be made use of by the detaining authorities for drawing the requisite subjective satisfaction for passing the

orders of detention. 3. As two of us constituting a Division Bench viewed that the interpretation of the term 'arrest' and the observation regarding the formal mode of arrest, given by the earlier Division Bench of this Court in Kaisar Otmar's case 1981 Cri LJ 208 are not in consonance with Section 46, Criminal P.C. and the view taken by a Full Bench of this Court in Collector of Customs v. Kothumal, MANU/TN/0218/1967 : AIR1967Mad263 and the decision of a Division Bench of the Bombay High Court in Harban Singh v. State, MANU/MH/0011/1970 : AIR1970Bom79 and that such an interpretation and observation need reconsideration by a Full Bench of this Court, we placed the matter before the Honourable the Chief Justice for necessary orders. Accordingly, this batch of writ petitions have now been referred to this Full Bench. 4. The relevant portion of the judgment in Kaisar Otmar's case 1981 Cri LJ 208 which led to this reference to this Full Bench, reads thus :"Our legal system does not require that an arrest should be attended with any ritual of even that it should be ostentatious. It is not necessary that a man in order to get arrested should be taken prisoner; nor does the law regard as arrest only the ceremonial hand-cuff or manacle. An authority is said to arrest another man if it prevents the latter from willing his movements and moving according to his will. Under enlightened modern conditions it seldom becomes necessary for any police officer or other authority empowered to make arrests to actually seize or even touch a person's body with a view to his restraint. Utterance of a guttural word or sound, a gesture of the index finger or hand, the sway of the head or even the flicker of an eye are enough to convey the meaning to the person concerned that he has lost his liberty." 5. In Kaiser Otmar's case 1981 Cri LJ 208, according to the detenu, he was taken for interrogation by the preventive officers of the Customs Department on the evening of 15th January, 1981 and thence forward was under their custody continuously till 4 p.m. on 18-1-1981 when he was produced before the Chief Metropolitan Magistrate and remanded to judicial custody, after 70 hours from the time of his being taken into custody i.e., his arrest. It was submitted on behalf of the respondents therein that the detenu was taken into custody on the 15th evening for inquiry and interrogation till 18-1-1981, during which he made a confessional statement leading to the recovery and seizure of smuggled goods and that he was actually arrested only at 11 a.m. on 18-1-1981 under Section 104(1) of the Customs Act, and that as the detenu was produced before the Magistrate on 18-1-1981 itself within 24 hours of the arrest, the submission made on behalf of the petitioner that there was an illegal detention violative of Article 22(2) of the Constitution, was not correct. In other words, according to the respondents, the detenu could not be said to have been 'arrested' within the meaning of the said term from the moment when he was taken into custody for interrogation. The Bench rejecting the contention of the respondents and accepting that of the petitioner, held that the detenu in that case was arrested from the time when he was taken into custody by the customs officials, i.e., on the evening of 15-1-1981 and kept for a prolonged period in violation of Article 22(2) of the Constitution. 6. In order to answer the reference, the following questions are framed for consideration :

(1) When is a person said to be under arrest ? (2) Are the terms 'custody' and 'arrest' synonymous ? (3) Are the customs officials vested with powers under the Customs Act, 1962 to detain any person for any period and at any place for the purpose of an inquiry, interrogation or investigation ? (4) Will the detention of a person by the customs officers for the purpose of inquiry, interrogation or investigation, amount to an 'arrest' of the said person ? (5) Is detention of a person by the customs officers for the purpose of inquiry or interrogation or investigation beyond 24 hours without producing him before a Magistrate, violative of Article 22 of the Constitution of India ? 7. Mr. Abdul Kareem, learned counsel appearing for the writ petitioners in W. P. Nos. 5016/83 and 5244/83, drew our attention to the various provisions of the Sea Customs Act, 1878 and the corresponding and other allied provisions of the Customs Act, 1962, as well as the various Provisions relating to arrest coming under Chapter IV, Cr.P.C., and submitted that the moment the personal liberty of a person and the freedom of his movement are restrained consequent upon his being brought under the custody of an authority clothed with the power of arrest, he should be deemed to have been arrested within the meaning of Section 46, Cr.P.C., and that though the subject of preventive detention is specifically dealt with in Article 22 of the Constitution, the requirement of Article 21 has nevertheless to be satisfied and that Sections 107 and 108 of the Customs Act vest an uncontrolled and unbridled power in an arbitrary, unreasonable and unguided manner, on the executive in implementing these provisions at their sweet will, which vesting is violative of the principles of natural justice and Article 21, and so the procedure attending upon such power of detention should conform to the mandate of Article 21 in the matter of fairness, justness and reasonableness and that the moment a person is arrested under Section 104(1) of the Customs Act, he must, without unnecessary delay, be taken to a Magistrate and that any prolonged delay in violation of Article 22(2) makes such detention illegal and hence any statement recorded from such arrested person or persons should be held to have been tainted with illegality as having been extorted under duress, coercion or undue influence and such a statement should not form the basis of the subjective satisfaction to be drawn by the detaining authority. 8. Mr. P. M. Jumma Khan, learned counsel appearing for the writ petitioner in W.P. Nos. 6192/83 and 6193/83, would adopt the argument advanced by Mr. Kareem. 9. Mr. Rangavajjula, learned counsel appearing for the petitioner in W.P. 6880/83, took us very meticulously through the various provisions of the Criminal Procedure Code, the Indian penal Code and the Customs Act and also the various text books written by renowned authors, in which terms 'arrest' and 'custody' appear, and also referred to various dictionaries with reference to the meaning of those two terms, and urged that the words 'arrest' and 'custody' are synonymous and therefore, once a person is taken for inquiry either under S. 107 or under S. 108, of the Customs Act, such a taking would amount to an arrest and the customs officials are

not at all justified in keeping and detaining a person as taken into custody for over the statutory period authorised under law, under the guise of inquiry or interrogation. According to him, the interpretation of the term 'arrest' and the observation of the term 'arrest' in Kaiser Otmar's case 1981 Cri LJ 208 represent the correct position of law and as such there is no warrant for reconsideration of the principles laid down therein. 10. The learned Advocate-General, appearing at the instance of this Court, posed three points as arising for discussion and answered the same stating (1) that the mere questioning of a person by a customs officer either under Section 107 or under Section 108 of the Customs Act resulting in a voluntary statement which may ultimately turn out to be incriminatory, is not compulsion, attracting the application of Section 20(3), because that person, while making that statement at that stage, is not an accused of any offence; (2) that as Sections 107 and 108 of the Customs Act provide ample sanction for inquiry or interrogating or investigation by the officers of the Customs Department without specifying the place and time for such inquiry etc., such exercise of the powers is in accordance with the procedure established by law within the meaning of Article 21 and as such there is no question of any violation of the provisions of Article 21 of the Constitution, and (3) that to attract Article 22(2) two essential ingredients, viz., 'arrest' and 'detention in custody' should be satisfied and therefore, the mere custody will not amount to arrest within its legal sense and as contemplated under Section 46, Cr.P.C. 11. Mr. P. Rajamanickam, the learned Public Prosecutor, appearing for respondents 1 and 2, counters the submissions made by the learned counsel appearing for the petitioners, inter alia contending that the mere taking of a person to a place convenient for all for the purpose of inquiry, interrogation or investigation, will not amount to 'arrest' though there is restraint of that person. According to him, when a statute becomes impossible of compliance and the duty imposed by that statute cannot be discharged, the doctrine of implied terms can be invoked and some auxiliary or incidental power can be permitted to exist lest the statutory provisions would become a dead letter and hence in an inquiry under S. 107 or Section 108 of the Customs Act, the authorities concerned can, by the application of the said doctrine, take persons suspected of having committed any offence to any place at any time for inquiry; interrogation etc., and such taking in the circumstances and context, would not amount to 'arrest' of the person concerned. 12. Mr. R. Thiagarajan, the learned Senior Central Government Standing Counsel, appearing on behalf of the third respondent, viz., the Assistant Director, Revenue, Intelligence, Madras, impleaded as per order of this Court dt. 9-9-1983 made in W.M.P. Nos. 12822 to 12824 of 1983, made reference to the scheme of the Customs Act and stated that a customs officer is not a police officer and the persons summoned for inquiry either under S. 107 or under S. 108 of the Customs Act is not an accused of an offence and hence at the stage of such an inquiry, when there is no formal accusation, the mere physical restraint of that person is not an arrest and in such a case there is no testimonial compulsion. He would further state that as the person summoned for inquiry does not have the character of an accused, the protection given under Articles 20(3), 21 and 22(2) of the Constitution cannot be availed of. 13. In support of their respective submissions, the learned counsel appearing for the various petitioners and the respondents and the learned Advocate-General took us very meticulously through a catena of decisions and also drew our attention to various provisions of the Customs

Act, the Code of Criminal Procedure and other allied enactments and certain renowned text books. 14. Meaning of the term 'arrest' : The term 'arrest' is not defined either in the procedural Acts or in the various substantive Acts, though Section 46, Cr.P.C., lays down the mode of arrest to be effected. 15. The word 'arrest' is derived from the French 'Arreter' meaning 'to stop or stay' and signifies a restraint of the person. Lexicographically the meaning of the word 'arrest' is given in various dictionaries as follows : a) In the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, the various meanings of the word used under various contexts are given. Those which are relevant for our purpose read thus : "As verb : 5. gen. to catch, lay hold upon; 6. Esp. to lay hold upon or apprehend by legal authority. As a noun : 3. The act of laying hold of; seizure. 4. Spec. The apprehending of one's person, in order to be forthcoming to answer an alleged or suspected crime. 5. Custody, imprisonment." b) The 'Webster's Third New International Dictionary, Vol. I, at page 121, gives the meaning thus : "1. arrest ........... 2. to catch or to take hold of; seize, capture. Specify : to take or keep in custody by authority of law. 3. a : to catch and hold ...................... 2 - arrest ........... 2.a : the act of seizing or taking hold of; seizure ......; the taking or detaining of a person in custody by authority of law; legal restraint of a person; custody, imprisonment ............." c) Stroud's Judicial Dictionary, IV Edition, Volume I, at page 184, defines the word as follows : "'arrest', is when one is taken and restrained from his liberty." d) In the Bouvier's Law Dictionary, 1914 Edition, Vol. I, the meaning is given thus : "Arrest : to deprive a person of his liberty by legal authority. The taking, seizing or detaining the person of another, touching or putting hands upon him in the execution of process, or any act indicating an intention to arrest ............" e) In the Dictionary of English Law (1959) by Earl Jowitt, Vol. I, the meaning of the word is given at page 152 as follows : "The restraining of the liberty of a man's person in order to compel obedience to the order of a Court of Justice, or to prevent the commission of a crime, or to ensure that a person charged or

suspected of a crime may be forthcoming to answer it. To arrest a person is to restrain him of his liberty by some lawful authority. f) The Wharton's Law Lexicon, 12th Edition (1916) has defined the word 'arrest' in the above lines. g) Black's Law Dictionary, 5th Edition (1979), gives the following definitions : "Arrest : To deprive a person of his liberty by legal authority. Taking, under real or assumed authority, custody of another for the purpose of holding or detaining him to answer a criminal charge or civil demand. ................ Arrest involves the authority to arrest, the assertion of that authority with the intent to effect an arrest, and the restraint of the person to be arrested ............. All that is required for an 'arrest' is some act by officer indicating his intention to detain or take person into custody and thereby subject that person to the actual control and will of the officer, as formal declaration of arrest is required. h) 'A Dictionary of Law' by L. B. Curzon (1979) gives the meaning of the word 'arrest' at page 22, as follows : "To restrain and detain a person by lawful authority .........." i) Mitra's Legal and Commercial Dictionary, Third Edition (1979), gives the following definition of the word at page 77 : "Arrest means the restraining of the liberty of a man's person in order to compel obedience to the order of a Court of Justice, or to prevent the commission of crime, or to ensure that a person charged or suspected of a crime may be forthcoming to answer it." "Arrest consists of the actual seizure or touching of a person's body with a view to his detention. The mere pronouncement of words of arrest is not an arrest, unless the person sought to be arrested submits to the process and goes with the arresting officer. An arrest may be made either with or without warrant ............" j) Words and Phrases legally defined, Second Edition (1969), Volume 1, at p. 114, gives the following definition : "Arrest consists of the actual seizure or touching of the person's body with a view to his detention. The mere pronouncement of words of arrest is not an arrest, unless the person sought to be arrested submits to the process and goes with the arresting officer ......... Arrest ........... is the apprehending or restraining of one's person, in order to be forthcoming to answer an alleged or suspected crime ............" k) The New Encyclopaedia Britannica, 15th Edition, Vol. 1, at page 540, states as follows about arrest :

"Arrest, placing of a person in custody or under restraint, usually for the purpose of compelling obedience to the law. If the arrest occurs in the course of criminal procedure, the purpose of the restraint is to hold the person for answer to a criminal charge or to prevent him from committing an offence. In civil proceedings, the purpose is to hold the person to a demand made against him ........" l) Halsbury's Laws of England, Third Edition (1955), Vol. 10, at page 342, states as follows : "631. Meaning of Arrest : Arrest consists of the actual seizure or touching of a person's body with a view to his detention. The mere pronouncement of words of arrest is not an arrest, unless the person sought to be arrested submits to the process and goes with the arresting person." m) Halsbury's Laws of England, IV Edition, Vol. II, in para 99 at page 75, states thus : "Meaning of arrest : Arrest consists in the seizure or touching of a person's body with a view to his restraint; words may, however, amount to an arrest if, in the circumstances of the case, they are calculated to bring and do bring, to a person's notice that he is under compulsion and he thereafter submits to the compulsion." (In the footnote, the following example is given for the second view mentioned above : Where a person is caught red-handed. (R. v. Howarth, (1828) 1 MCC 207). Also Gelberg v. Miller, (1961) 1 All ER 291.) n) The Corpus Juris Secondum, Vol. VI, at page 570, gives the meaning of the word 'arrest' when used in criminal charges, as follows : "In criminal procedure, an arrest is the taking of a person into custody in order that he may be held to answer for or be prevented from committing a criminal offence .......... consists in the taking into custody of another person under real or assumed authority for the purpose of holding or detaining him to answer a criminal charge or of preventing the commission of a criminal offence ........... The terms 'arrest' and 'apprehension' have been by some Courts used interchangeably as meaning the same thing when employed in connection with the taking of a person into custody. The effect of facts as constituting an arrest is a question of law. Whether the particular circumstances have been established which constitute an arrest is ordinarily, however, a question of fact." According to this text book, "to constitute an arrest, there must be an intent to arrest, under a real or pretended authority, accompanied by a seizure or detention of the person, which is so understood by the person arrested". o) In "A Hand-Book in Criminal Procedure and the Administration of Justice" by Alien P. Bristow and John B. Williams, at 834 P.C., it is stated that an arrest is taking a person into custody in a case and in the manner authorised by law. At 835 P.C., it is stated that an arrest is

made by an actual restraint of the person or by submission to the custody of an officer. p) In another text-book "The Criminal Prosecution in England" by Patrick Devlin, at page 68, the author has expressed his view as follows : "The police have no power to detain any one unless they charge him with a specified crime and arrest him accordingly. Arrest and imprisonment are in law the same thing. Any form of physical restraint is an arrest and imprisonment is only a continuing arrest. If an arrest is unjustified, it is wrongful in law and is known as false imprisonment ..........." q) Winn, L.J., in R. v. Palferey; R. v. Sadler (1970) 2 All ER 12, when delivering the judgment of Court of which Lord Parker, C.J., was a member, said, in explaining the term 'arrest' : "It is not a question whether or not certain conditions precedent have been satisfied. The question is merely whether or not he is a person who is under arrest; whether he is under arrest or not depends on whether he is free to go as he pleases, or has been told that he is in a state of custody." r) In Spicer v. Holt (1976) 3 All ER 71, Viscount Dilhorne, following the above view of Winn, L.J., has observed thus : "'Arrest' is an ordinary English word and its natural meaning is that given to it by Winn, L.J., which I have cited. Whether or not a person has been arrested depends not on the legality of the arrest, but on whether he has been deprived of his liberty to go where he pleases." 16. From the various definitions which we have extracted above, it is clear that the word 'arrest', when used in its ordinary and natural sense, means the apprehension or restraint or the deprivation of one's personal liberty. The question whether the person is under arrest or not, depends not on the legality of the arrest, but on whether he has been deprived of his personal liberty to go where he pleases. When used in the legal sense in the procedure connected with criminal offences, an arrest consists in the taking into custody of another person under authority empowered by law, for the purpose of holding or detaining him to answer a criminal charge or of preventing the commission of a criminal offence. The essential elements to constitute an arrest in the above sense are that there must be an intent to arrest under the authority, accompanied by a seizure or detention of the person in the manner known to law, which is so understood by the person arrested. In this connection, a debatable question that arises for our consideration is whether the mere taking into custody of a person by an authority empowered to arrest would amount to 'arrest' of that person and whether the terms 'arrest' and 'custody' are synonymous. 17. (a) The term 'custody' appears in a number of enactments. However, we are not giving an exhaustive list of the provisions of enactments containing the said expression 'custody'. In Sections 439, 442 (heading alone of the section) and S. 451 of the Criminal Procedure Code, Section 223 of the Indian Penal Code, Sections 26 and 27 of the Indian Evidence Act, S. 45 of the Customs Act, 1962 and Sections 19(c) , 25(b) and (c), 29(2) and (3) and 40 of the Tamil Nadu Children Act, etc., the said term is used. However, it may be noted that the said word is not

defined in any of these enactments. (b) The meaning of the term 'custody' is given in the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, as follows : "1. Safe-keeping, protection, charge, care, guardianship. 2. The keeping of an officer of justice, confinement, imprisonment, durance. 3. Guardianship." (c) In Webster's Third International Dictionary, Vol. I, at page 559, the word 'custody' is given the following meanings : "1.a. The act or duty of guarding and preserving, safe-keeping, b. Judicial or penal safe-keeping, control of a thing or person with such actual or constructive possession as fulfils the purpose of the law or duty requiring it; imprisonment or durance of persons or charge of things." ........ The term 'custody' implies and signifies various meanings dependent upon the context in which the term is used." (d) The Corpus Juris Secondum, Vol. 25, at page 69 when it is applied to persons, it implies restraint and may or may not imply physical force sufficient to restrain depending on the circumstances and with reference to persons charged with crime, it has been defined as meaning on actual confinement or the present means of enforcing it, the detention of the person contrary to his will. Applied to things, it means to have a charge or safe-keeping, and connotes control and includes as well, although it does not require, the element of physical or manual possession, implying a temporary physical control merely and responsibility for the protection and preservation of the thing in custody. So used, the word does not connote dominion or supremacy of authority. The said term has been defined as meaning the keeping, guarding, care, watch, inspection, preservation or security of a thing, and carries with it the idea of the thing being within the immediate personal care and control of the prisoner to whose custody it is subjected; charge; charge to keep, subject to order or direction; immediate charge and control and not the final absolute control of ownership. 17-A. Therefore, it is clear that we have to take the meaning of the term 'custody' with reference to the context in which it is used. 18. Mr. Rangavajjula would submit that when a person is said to have been taken into custody by an authority empowered to arrest, it implies the imposition of actual physical restraint or the detention of the person concerned, resulting in the loss of his personal liberty and therefore it amounts to 'arrest'. A contention similar to this was raised in State of Punjab v. Ajaib Singh MANU/SC/0024/1952 : 1953CriLJ180 . In that case, the point for consideration was whether the taking into custody of an abducted person by a police officer under Section 4 of the Abducted Persons' (Recovery and Restoration) Act, 1949 (Act 65 of 1949) and the delivery of such person by him into the custody of the officer in charge of the nearest camp can be regarded as arrest and detention within the meaning of Article 22(1) and (2). It was contended in that case, after

referring to the various definitions of the word 'arrest' given in several well known law dictionaries and urged in the light of such definitions, that any physical restraint imposed upon a person must result in the loss of his personal liberty and must accordingly amount to his arrest and that it is wholly immaterial why or with what purpose such arrest is made and the mere imposition of physical restraint, irrespective of its reason, is arrest and as such attracts the application of the constitutional safeguards guaranteed under Article 22(1) and (2). While meeting that argument, the Court observed : "That the result of placing such wide definition on the term 'arrest' occurring in Article 22(1) will render many enactments unconstitutional, is obvious. To take one example, the arrest of a defendant before judgment under the provisions of O. 38, R. 1, C.P.C. or the arrest of a judgment-debtor in execution of a decree under S. 55 of the Code will, on this hypothesis, be unconstitutional inasmuch as the Code provides for the production of the arrested person, not before a Magistrate but before the Civil Court which made the order." A Division Bench of the Bombay High Court, in Harban Singh v. State ( MANU/MH/0011/1970 : AIR1970Bom79 , wherein the interpretation of the terms 'arrest' and 'custody' arose for decision while dealing with Section 104(2) of the Customs Act, held as follows :"Arrest is a mode of formally taking a person in police custody, but a person may be in the custody of the police in other ways. What amounts to arrest is laid down by the legislature in express terms in S. 46, Cr.P.C., whereas the words 'in custody' which are to be found in certain sections of the Evidence Act only denote surveillance or restriction on the movement of the person concerned, which may be complete, as, for instance, in the case of an arrested person, or may be partial. The concept of being in custody cannot therefore be equated with the concept of a formal arrest and there is difference between the two. Where, after the statements recorded by the Customs Authorities, due to the night-fall, the accused are put up before a Magistrate only next morning, it cannot be said that the accused were arrested and as such any statement made by them cannot be said to be in violation of Section 24 of the Evidence Act. ........ In my opinion, however, the mere fact that there may be some restriction on the movements of the accused or that the accused person may be in some sort of surveillance at the time when he makes the confession would not ipso facto vitiate the confession as being involuntary." In support of his proposition, Mr. Rangavajjula would draw the attention of this Court to the decision of the Supreme Court in Niranjan Singh v. Prabhakar, MANU/SC/0182/1980 : 1980CriLJ426 , wherein S. 439, Cr.P.C. came up for consideration. In that case, the Supreme Court posed a question for consideration and answered the same as follows : "When is a person in custody within the meaning of S. 439, Cr.P.C. ? When he is in duress either because he is held by the investigating agency or other police or allied authority or is under the control of the Court, having been remanded by judicial order or having offered himself to the Court's jurisdiction and submitted to its order by physical presence. No lexical dexterity or precedential profession is needed to come to the realistic conclusion that he who is under the control of the Court or in the physical hold of an officer with coercive power is in custody for the purpose of Section 439. This word is of elastic semantics and its core meaning is that the law

has taken control of the person. Equivocatory quibblings and the hide-and-seek niceties sometimes heard in Court that the police have taken a man into informal custody but not arrested him, have detained him for interrogation but not taken him into formal custody and the other like terminological dubieties (sic) are unfair evasions of the straight-forwardness of the law. We need not dilate on this shady facet here because we are satisfied that the accused did physically submit before the Sessions Judge and the jurisdiction to grant bail thus arose. Custody in the context of S. 439 (we are not, be it noted, dealing with anticipatory bail under S. 438) is physical control or at least physical presence of the accused in Court with submission to the jurisdiction and order of the Court. He can be in custody not merely when the police arrests him, produces him before a Magistrate and gets a remand to judicial or other custody. He can be stated to be in judicial custody when he surrenders before the Court and submits to its directions." 19. In order to fully understand the above view expressed by the Supreme Court, let us have a cursory glance of Section 439, Cr.P.C. (which corresponds to S. 498 of the old Code). The unfettered discretionary power of the High Court and the Court of Session under Section 439 of the Code in granting bail can be exercised only on the satisfaction of two conditions : Firstly, the person who moves for bail must be a person accused of an offence, bailable or non-bailable, and secondly he must be in custody. The Supreme Court in Niranjan Singh's case MANU/SC/0182/1980 : 1980CriLJ426 , on being satisfied that the first condition has been fulfilled, gave the meaning of the term 'in custody' while considering the fulfilled of the second condition. Be it noted that in the said case their Lordships did not express the view that the mere taking of a person into custody by an authority empowered to arrest, or the mere presence of the accused is enough to constitute the arrest of the accused, but only emphasized that the physical control or at least physical appearance of the accused in Court should be coupled with the submission to the jurisdiction and orders of the Court. In other words, the person who is accused of an offence should submit himself to the jurisdiction or orders of the authority empowered to arrest. 20. Coming to the Customs Act, a person who appears before any officer of Customs on being required for an enquiry in connection with the smuggling of any goods, under Section 107 of the Customs Act, or a person who attends before any gazetted officer of Customs on summons in connection with an enquiry relating to the smuggling of any goods, under S. 108 of the said Act, is not a person accused of an offence at that stage. Therefore, the submission of Mr. Rangavajjula that since the person so required or summoned under the above said provisions comes under the custody of the Customs Officials, he must be deemed to have been arrested in the light of the interpretation by the Supreme Court of the term 'in custody' occurring in S. 439 of the Code in Niranjan's case (1980 Cr LJ 426), cannot be accepted. In fact, their Lordships themselves have pointed out in that judgment that there is a shady facet in the expression of the term in 'custody'. Hence, this decision cannot be availed of by the learned counsel in support of his contention that the mere taking of a person into custody would amount to arrest. 21. Now, We shall pass on to discuss about the interpretation of the same term 'in custody' occurring in Sections 26 and 27 of the Evidence Act. In Laymaung v. Emperor, AIR 1924 Rang 173 : 1924 Cri LJ 381, it was said by the learned Judges in that case that the correct interpretation of the term 'police custody' would be that 'as soon as an accused or suspected

person comes into the hands of a police officer, is, in the absence of any clear and unmistakable evidence to the contrary, no longer at liberty and is therefore in custody within the meaning of Sections 26 and 27 of the Evidence Act." See also Paramhansa v. State of Orissa, MANU/OR/0057/1964 : AIR1964Ori144 . It has been held in Gurdial Singh v. Emperor, AIR 1932 Lah 609 : 1932 Cri LJ 756 and in Re : Edukondalu, MANU/AP/0070/1957 that there may be police custody even without formal arrest. The Supreme Court in State of Uttar Pradesh v. Deoman, MANU/SC/0060/1960 : 1960CriLJ1504 , has observed thus : "Section 46, Cr.P.C. does not contemplate any formality before a person can be said to be taken in custody. Submission to the custody by words of mouth or action by a person is sufficient. A person directly giving a police officer by word of mouth information which may be used as evidence against him may be deemed to have submitted himself to the custody of the Police Officer." The principle stated in that case is to the effect that when a person not in custody approaches a police officer investigating an offence and offers to give information leading to the discovery of a fact having a bearing on the charge which may be made against him, he may appropriately be deemed to have surrendered himself before the police. See also Soni Vallabhdas Liladhar v. Assistant Collector of Customs, AIR 1965 SC 481 : 1965 Cri LJ 490. Reiterating and expanding this view taken in Deoman's case, MANU/SC/0060/1960 : 1960CriLJ1504 , the Supreme Court in Gurbakh Singh v. State of Punjab, MANU/SC/0215/1980 : 1980CriLJ1125 , while examining the scope of anticipatory bail under Section 438, Cr.P.C. has observed thus (at page 1137 of Cri.L.J.) : "While granting relief under S. 438(1), appropriate conditions can be imposed under Section 438(2) so as to ensure an uninterrupted investigation. One of such conditions can even be that in the event of the police making out a case of a likely discovery under S. 27 of the Evidence Act, the person released on bail shall be liable to be taken in police custody for facilitating the discovery. Besides, if and when the occasion arises, it may be possible for the prosecution to claim the benefit of S. 27 of the Evidence Act in regard to discovery of facts made in pursuance of information supplied by a person released on bail by invoking the principles stated by this Court in State of Uttar Pradesh v. Deoman Upadhyaya, MANU/SC/0060/1960 : 1960CriLJ1504 ." See also Legal Remembrancer v. Lalit Mohan Singh, MANU/WB/0308/1921 : AIR1922Cal342 ; Santokhi v. Emperor, AIR 1933 Pat 149 : 1933 Cri LJ 349; and also Bharosa Ram Dayal v. Emperor, MANU/NA/0141/1940 : AIR 1941 Nag 86 : 1941Cri LJ 390. 22. At this stage the decision of a Division Bench of this Court in Ramchandra in re, MANU/TN/0335/1959 was brought to our notice. The facts of the case disclose that while the accused therein was in judicial custody in pursuance of the judicial remand, he was interviewed by the Inspector of Police to whom he gave some information. Subsequently, the accused on the order of the Magistrate, came to police custody. Thereafter, the Inspector discovered a relevant fact in pursuance of the information given by the accused while he was in jail custody. The question arose whether that part of the information leading to the discovery of the relevant fact, while the accused was in jail custody could be proved within the scope of S. 27. The Division

Bench, observing that there should not be a rigid interpretation of S. 27, held thus : "Though, formally, the accused was in judicial custody under an order of remand made by the Magistrate, he was temporarily in the custody of the Police Officer when he was interrogated and must be held to have been in such custody for the purpose of the applicability of S. 27." A close study of the above decision shows that the Bench had taken the view that though the accused was in jail, he must be deemed to have been in temporary custody of the police at the time of the interrogation, which position, in our view cannot be recognized in law. With great respect to the learned Judges, we feel that such an extreme view would lead to an anomalous position in the sense that the accused should be presumed to have been both in judicial custody and the temporary custody of the police at the time of his interrogation and that the said view cannot be in strict compliance with Section 27 of the Evidence Act, which envisages that the accused should be in custody of the Police Officer at the time of making confession leading to the discovery of a relevant fact. The decision of the Supreme Court cited in that case, viz., Ramkishan v. Bombay State, MANU/SC/0044/1954 : 1955CriLJ196 does not support that extreme proposition, but on the other hand, in para 23, (at p. 116 of AIR SC) : (at p. 208 of Cri LJ), it was observed that the statement or part thereof relating to the discovery of a fact can be proved only when it comes within the four corners of Section 27. There are cases of this Court bearing on this particular question of the nature of the custody generally assuming that unless the accused be in police custody formally authorised, or in such custody after arrest, Section 27 would not apply. See Peria Gurusami Goundar v. Emperor, 1941 Mad WN (Cri) 94 : AIR. 1941 Mad 765 : 1942 Cri LJ 100 and in re Kamakshi Naidu, MANU/TN/0129/1942 : AIR 1943 Mad 89 : 1943 Cri LJ 304. This may be explained in another way also. The police may arrest a person and detain him in custody for a maximum period of 24 hours for the purpose of investigation and if the investigation cannot be completed within the specified period, the police shall produce the accused before a Magistrate for remand - that is, judicial custody - as contemplated under Section 167(1), Cr.P.C. The Magistrate who takes the accused into judicial custody can pass orders authorising further police custody under Section 167(2). Here, when the police take the accused back to police custody, such a custody becomes a police custody; but it does not imply the re-arrest of the accused. Hence, the information given to the police leading to the discovery of a relevant fact is said to have been given to the police while he is in the custody of the Police Officer. It is pertinent to note that Sections 26 and 27 of the Evidence Act speak about the admissibility or otherwise of a statement of 'a person accused of any offence in the custody of a police officer'. The word 'arrest' is not used in either of those two sections. Thus, the Legislature has in its wisdom, designedly, used the expression 'in the custody of a police officer' so that there may not arise any legal conundrum even in a case where a statement is made by a person accused of any offence to an authority empowered to arrest him, though not actually arrested but has come only in his custody. 23. It was contended on behalf of the writ petitioners that applying the interpretation of the expression 'in custody' appearing in Sections 26 and 27 of the Evidence Act, it should be held that a person who is taken by a Customs Officer either for the purpose of enquiry or interrogation or investigation, should be held to have come into the custody and detention of the Customs Officer and he should be deemed to have been arrested from the moment he was so taken into custody. We cannot agree with this submission for a number of reasons; Firstly, the specified

Customs Officer is empowered to require or summon any person for the purpose of an enquiry or examination in connection with the smuggling of any goods, either under Section 107 or under Section 108 of the Customs Act, as the case may be. Secondly, it is well settled that Customs Officers whose powers are for the purpose of checking the smuggling of goods and the due realization of the Customs Duties and determining the action to be taken in the interest of the revenue of the country by way of confiscation of goods on which no duty had been paid and by imposing penalties and fines, and who are not primarily concerned with the detection and punishment of the crimes committed by those persons but only interested in the detection and prevention of the smuggling of goods and the safeguarding the recovery of customs duties are not police officers. See State of Punjab v. Barkatram, MANU/SC/0021/1961 : [1962]3SCR338 ; Collector of Customs v. Kothumal, MANU/TN/0218/1967 : AIR1967Mad263 (FB); Illias v. Collector of Customs, Madras, MANU/SC/0297/1968 : 1970CriLJ998 and Ramesh Chandra Mehta v. State of West Bengal, MANU/SC/0282/1968 : 1970CriLJ863 . Thirdly, a Custom Officer is not a Court, as held in Hira H. Advani v. State of Maharashtra, MANU/SC/0102/1969 : 1971CriLJ5 . Fourthly, when an enquiry is being conducted under Section 107, or under Section 108 of the Customs Act and a statement is given by a person against whom the enquiry is being held, it is not a statement made by a person who stands in the character of an accused person, as found in Percy Rustomji v. State of Maharashtra, MANU/SC/0161/1971 : 1971CriLJ933 and Ramesh Chandra v. State of West Bengal, MANU/SC/0282/1968 : 1970CriLJ863 . Fifthly, any statement made by a person before the Customs Officer is not hit by Section 25 of the Evidence Act as he is not a police officer. See Badaku Joti Svant v. State of Mysore, MANU/SC/0276/1966 : 1966CriLJ1353 . Sixthly, the machinery created under the Customs Act is not one for the purpose of investigation into crimes and it is only the side effect resulting from the enforcement of the Customs Act that certain offences are detected and therefore, investigation of the Customs Crimes under the Act is not an investigation as defined in the Criminal Procedure Code : Vide, State of Maharashtra v. Lakshmi Chand Varhomal, MANU/MH/0341/1977; Assistant Collector of Central Excise, Preventive, Madras v. Krishnamoorthy, MANU/TN/0012/1983. Also see State of Uttar Pradesh v. Durga Prasad, MANU/SC/0216/1974 : 1974CriLJ1465 ; Barkat Ram's case MANU/SC/0021/1961 : [1962]3SCR338 ; Eknath v. State of Maharashtra, MANU/SC/0087/1977 : 1977CriLJ964 and State of Maharashtra v. Mahipathi, MANU/SC/0147/1977 : 1977CriLJ968 , all these latter cases holding that the investigation carried on by the officer of the Railway Protection Force, the Officer under the Prevention of Food Adulteration Act and the Forest Officer under the Indian Forest Act, is not an investigation as defined under Section 2(h), Cr.P.C. It is worthwhile to refer at this juncture to the Judgment of a Full Bench of this Court in Collector of Customs v. Kotmal, MANU/TN/0218/1967 : AIR1967Mad263 (FB), wherein it has been pointed that neither the enquiry under Section 107 nor the enquiry under Section 108 of the Customs Act can in any way, in substance or in law, be considered to be the same as an investigation into the criminal offence by an officer in charge of a police station under Chapter XIV of the old Code, which is the primary test for the application of Section 25 of the Evidence Act. Seventhly, the Supreme Court in Veera Ibrahim v. State of Maharashtra, MANU/SC/0514/1976 : 1976CriLJ860 , agreeing with the principle laid down in Mehta v. State of West Bengal, MANU/SC/0282/1968 : 1970CriLJ863 , held that when the statement of a person is recorded by the customs officer under Section 108, that person is not a person 'accused of any offence' under the Customs Act and that an accusation which would stamp him with the character of such a person was levelled only when the complaint was filed against him by the Assistant Collector of Customs complaining of the

commission of the offences under Section 135(a) and under S. 135(b) of the Customs Act. 24. Mr. Kareem, relying (1) on the decision in Francis Coralie v. Union Territory of Delhi, MANU/SC/0517/1981 : 1981CriLJ306 wherein it has been observed that the right to life enshrined in Article 21 cannot be restricted to mere animal existence and it means something much more than just physical survival, (2) on the observation of the Supreme Court in Malak Singh v. State of Punjab, MANU/SC/0157/1980 : 1981CriLJ320 reading, "Surveillance may be intrusive and it may so seriously encroach on the privacy of a citizen as to infringe his fundamental right to personal liberty guaranteed by Article 21 of the Constitution and the freedom of movement in Article 19(1)(d). That cannot be permitted", and also (3) on the principle laid down in Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India, MANU/SC/0133/1978 : [1978]2SCR621 wherein it has been said that the right of free movement is vital element of personal liberty, submitted that in view of the above principles laid down by the Supreme Court in the above decisions, any kind of surveillance or restriction on the movement of the person concerned cannot be permitted and that the Bombay High Court in Harban Singh v. State, MANU/MH/0011/1970 : AIR1970Bom79 has not considered this position of law. In answering this contention, Mr. Thiagarajan, learned Senior Central Government Standing Counsel, would submit that when a customs officer exercising authority either under Section 107 or under Section 108 of the Customs Act is not a police officer and the person interrogated is not a person accused of an offence and so the protection given under Articles 20(3), 21 and 22 of the Constitution cannot be availed of. The learned Advocate General urges that a person is required under Section 107 and summoned under Section 108 for the purpose of an enquiry in connection with the smuggling of any goods and hence such an enquiry or interrogation or investigation receives sanction from the said statutory provisions, which is a procedure established by law within the meaning of Article 21 and so it cannot be said that such an enquiry, investigation or interrogation will be violative of Article 21. In other words, such an enquiry, interrogation or investigation of a person under the Customs Act is not without a statutory sanction and therefore the contention of Mr. Kareem that there is a violation of personal liberty by the customs officials in summoning the person for enquiry or interrogation cannot be accepted. In support of this contention, the learned Advocate General cited the decision of the Supreme Court in Balakrishna v. State of West Bengal, MANU/SC/0201/1973 : 1974CriLJ280 , wherein Krishna Iyer, J., has made the following observation : "This provision is wide in its terms and is clearly designed to facilitate the investigatory process by examination without restriction on person, place or time. Lest it should be misused the law is choosy and requires the empowerment of customs officers by a general or special power of the Collector to exercise these larger powers. Does S. 107 enable the interrogation of even the potential delinquent or must it be confined only to witnesses who throw light on the delinquent's contravention of the law ? 'Any person' in the section certainly covers every person including a suspect and potential accused. These words of the statute have to be interpreted in the light of the policy and purpose of the law. The object of S. 107, located in the neighbourhood of Section 108, indicates that while the normal process of enquiry is facilitated by Section 108, investigatory emergencies are taken care of by Section 107. May be situations arise where the failure to question a witness quickly may mean irretrievable loss of a valuable material and Section 107 meets this need. The context in which the words 'any person' occur, the object of the provision and the policy underlying Chapter XIII of the Customs Act assume relevance and

become material in the construction of the text. Nor are we faced with any difficulty on account of Article 20(3) of the Constitution since the examination is not of an accused person." 25. As regards the question of surveillance, in Malak Singh's case MANU/SC/0157/1980 : 1981CriLJ320 itself, the Supreme Court observed that so long as surveillance is for the purpose of preventing crime and is confined to the limits prescribed under the specified provisions, a person whose name is included in the surveillance register cannot have a genuine cause for complaint. The Supreme Court has further pointed out that interference in accordance with the law and for the prevention of disorder and crime is an exception recognised even by the European Convention of Human Rights to the right to respect for a person's private and family life, and ultimately pointed out thus : "As we said, discrete surveillance of suspect, habitual and potential offenders, may be necessary and so the maintenance of history sheet and surveillance register may be necessary too, for the purpose of prevention of crime. History sheets and surveillance registers have to be and are potential documents. Neither the person whose name is entered in the register nor any member of the public can have access to the surveillance register. The nature and character of an entry in the surveillance register is so utterly administrative and non-judicial that it is difficult to conceive of the application of the rule of audi alteram partem. Such enquiry as may be made has necessarily to be confidential and it appears to us to necessarily exclude the application of that principle. In fact, observance of the principles of natural justice may defeat the very object of the rule providing for surveillance. There is every possibility of ends of justice being defeated instead of being served." What their Lordships have stated in the judgment is that there should not be excessive surveillance falling beyond the limits prescribed by the rules and in such a case a citizen would certainly be entitled to the Courts' protection and that there should not be any illegal interference in the guise of surveillance and therefore the surveillance has to be unobtrusive and within bounds. Further, as held by the Supreme Court in Raja Narayanlal Bansilal v. Maneck Phiroz Mistry, MANU/SC/0016/1960 : [1961]1SCR417 , reiterated in a number of later decisions inclusive of Nandini Satpathy v. P. L. Dani, MANU/SC/0139/1978 : 1978CriLJ968 "One of the essential conditions for invoking the constitutional guarantee enshrined in Article 20(3) is that a formal accusation relating to the commission of an offence which would normally lead to his prosecution must have been levelled against the party who is being compelled to give evidence against him." See also State of Bombay v. Kathi Kalu, MANU/SC/0134/1961 : 1961CriLJ856 ; Popular Bank v. Madhava Naik, MANU/SC/0317/1964 : AIR1965SC654 ; Collector of Customs v. Kothumal, MANU/TN/0218/1967 : AIR1967Mad263 (FB); Yusuf Ali Ismail Nagri v. State of Maharashtra, MANU/SC/0092/1967 : 1968CriLJ103 and Veera Ibrahim v. State of Maharashtra, MANU/SC/0514/1976 : 1976CriLJ860 . In this connection, Mr. Kareem would state that the above conditions for invoking Article 20(3) is not in dispute. 26. In Harban Singh's case MANU/MH/0011/1970 : AIR1970Bom79 what the Division Bench of the Bombay High Court observed was that the words 'in custody' which are to be found in

certain sections of Evidence Act denote surveillance or restriction on the movements of the person concerned. We feel that we need not elaborately deal with the judgment of the Bombay High Court since we have exhaustively discussed supra, the question of custody and surveillance. In this connection, we would like to point out that Section 24 of the Evidence Act bars the use of a confession made by an accused person as irrelevant in a criminal proceeding if it appears to the Court that the confession had been obtained by inducement, threat or promise having reference to the charge against the accused person. Section 25 reads that no confession made to a police officer shall be proved as against a person accused of any offence. In a proceeding under the provisions of the Customs Act, when any person is required or summoned for an enquiry under Section 107 or Section 108, that person is not an accused person and the officer summoning that person is not a police officer. Any confession made by a person summoned under S. 107 or S. 108 before the Customs Officer is admissible in law since it is not hit either by S. 25 or S. 26 of the Evidence Act. If it is shown in a given case that such a confession was obtained by the Customs Officer by exertion of inducement, threat, coercion or duress or extracted by illegally detaining the person in an unauthorised prolonged custody in contravention of the provisions of the Customs Act, or obtained by using Third Degree methods, then the question about the acceptability and reliability of such involuntary confessions would arise. What Mr. Kareem complains is that a person in such an enquiry is virtually taken as a prisoner into the Customs House and taken hither and thither by the preventive officer of the Customs Department and during that period the degree of freedom of the person concerned in the company of the Customs Officer is only a mystery and that in fact he is in the captivity of the Customs Officials, sleeping in the bosom of the Customs House as a non-paying guest without stirring out of the Customs House for days together and as such he is quite unable to go anywhere he likes or wishes, but is being dogged by the Customs Official all the while and he is completely under their will and surveillance. He also, placing reliance in the observations of the Supreme Court in Nandini Sathpathy's case MANU/SC/0139/1978 : 1978CriLJ968 , made a scathing attack about the in communicado interrogations and submitted that such interrogations are not only derogatory and degrading, but also violative of Article 21 of the Constitution. This kind of complaint can be examined and decided only with reference to the facts of each case and one cannot make any general proposition of law about the conduct of the Customs Officers in general in the matter of enquiry, interrogation or investigation, based on any assumption or conjecture. 27. In an enquiry held under Section 107 or Section 108 of the Customs Act, not only the persons who subsequently may become the accused with reference to the matter under enquiry, but also persons who are conversant or suspected to be conversant with the smuggling of any goods, are examined. This is the reason why in the said sections the words 'any person' are used so as to denote all the persons inclusive of the persons who subsequently become accused. At that stage, there is no question of arrest. Arrest comes into the picture only when an officer of the Customs empowered in this behalf by general or special order of the Collector of Customs has reason to believe that any person has been guilty of an offence punishable under Section 135. Sections 107 and 108, as they stand, do not give any power to the Customs Officer to take any person under compulsion and detain him for a prolonged period under the guise of enquiry, investigation or interrogation. The statutory threat embodied in sub-section (4) of Section 108 is to the effect that in case the person summoned to give evidence and produce documents in connection with the enquiry relating to the smuggling of any goods, fails to do so or gives a false statement, he will

be liable to be proceeded against under Section 193 or Section 228, I.P.C. and for that purpose, that enquiry is to be deemed to be a judicial proceeding within the meaning of the abovesaid penal provisions. Section 107 and Section 108 are analogous to the provisions of S. 160(1), Cr.P.C. As rightly pointed out by the Advocate General if a person appears before a Customs Officer in compliance with the summons for the purpose of giving information or evidence, as in the case of a person appearing before a police officer under Section 160(1), Cr.P.C. can it be said that such a person comes into the custody of the Customs Officer concerned, amounting to arrest ? In our view, there is no such custody amounting to an arrest in such a situation. Further, as rightly pointed out by Mr. P. Rajamanickam, the learned Public Prosecutor, there is no question of surveillance, official or unofficial, in summoning a person for interrogation, and a person taken for interrogation cannot be said to have been arrested within the meaning of the said term. If such wide interpretation is given then even the attendance of a person before a police officer under Section 160(1), Cr.P.C. would amount to an arrest. That is definitely not the law. 28. Yet another argument was advanced that when a Customs Officer takes a person into his custody under the guise of making an enquiry or interrogation, or for the purpose of investigation, it would be similar to an offence of wrongful restraint as defined in Section 339, I.P.C., punishable under Section 241, I.P.C. or an offence of wrongful confinement as defined in Section 340 punishable under Section 342, I.P.C. This argument is totally misconceived, because it is only an officer authorised by law to do so, does so. 29. For all the discussions made above, we hold that 'custody' and 'arrest' are not synonymous terms. It is true that in every arrest there is a custody, but not vice versa. A custody may amount to an arrest in certain cases but not in all cases. In our view, the interpretation that the two terms 'custody' and 'arrest' are synonymous is an ultra legalist interpretation, which if accepted and adopted, would lead to a startling anomaly resulting in serious consequences. 30. Mode of arrest :- This is a crucial question in those cases which has led to the constitution of this Full Bench. Section 36(1), Cr.P.C. under the heading 'arrest how made' coming, under Chapter 5 with the caption 'arrest of persons' reads thus : "(1) In making an arrest the Police Officer or other person making the same shall actually touch or confine the body of the person to be arrested, unless there be a submission to the custody by word or action. (2) .. ... ... ... ... (3) .. ... ... ... ..." The above section applies to all arrests whether made under a warrant or without a warrant, and prescribe the mode of arrest. The Criminal Procedure Code contains various provisions by and under which various authorities and private persons are empowered to arrest. An analysis of the provisions under this Chapter shows that a person may be arrested by "(1) a police officer without a warrant under Sections 41(1) and 151; under a warrant under Sections 72 and 74; under the written order of an officer in charge of a police station under

Sections 55 and 157; under the orders of a Magistrate under Section 44 and in non-cognizable offence under Section 42; (2) a superior police officer under S. 36; (3) an officer in charge of a police station under Sections 41(2) and 157; (4) a Magistrate under S. 44; (5) a military officer under Sections 130 and 131; and (6) a private person without warrant under S. 43; under a warrant under Sections 72 and 73; under the orders of the police officer under S. 37, and under the orders of a Magistrate under Sections 37 and 44." The modality of arrest as contemplated under Section 46 is that while making an arrest, a police officer or other person making the same (arrester) "(1) Should actually touch the body of the person to be arrested or (2) Should actually confine the body of the person to be arrested." These kinds of modality of arrest are not necessary in case the person intended to be arrested submits, either by word or by action, to the authority of the arrester. In other words, if the person to be arrested submits to the authority or control of the arrester, the latter need not actually touch or confine the body of the person to be arrested. Conversely, if he does not so submit himself to the authority of the arrester, any of the two conditions mentioned above, viz., the touching or confinement of the body of the person to be arrested should be satisfied. 31. In Emperor v. Lallu Bachji, 1919 Cri LJ 391 : AIR 1919 Bom 39. It has been pointed out that the English common law rule is that except in case of submission, arrest of a person consists of the actual seizure or touching of the body of a person with a view to his detention and that this rule would no doubt be followed in India, although there is no express authority on the subject. 32. The Nagpur Judicial Commissioner's Court in Hari Mohanlal v. Emperor, 1929 Cri LJ 128 (Nag) (has held) that there can be no arrest within the meaning of Section 45(1), Cr.P.C. unless the person to be arrested is actually touched by the process server and that an arrest by mere oral declaration is not legal, and there can be no conviction under Section 225, I.P.C. (Resistance or obstruction of lawful apprehension or escape of or rescue in cases not otherwise provided for) of a person who is so arrested. 33. In Campbell v. Tormey, 1969 1 WLR 189, it was ruled that voluntary attendance at a police station is not an arrest. In the light of the decision in Campbell case, there are Indian decisions also holding the view that mere attendance or uttering of words not in conformity with the provisions of Section 45, Cr.P.C. does not amount to arrest. Vide in Re Amarnath, 1883 ILR 5

All 318. 34. Before the Queen's Bench Division, in Alderson v. Booth, 1969 All ER 271, an interesting question came up for consideration as to whether the accused in that case had been arrested after the first breath test under S. 2(4) of the Road Safety Act, 1967. Lord Parker, C.J. speaking for himself, observed thus : "There are a number of cases, both ancient and modern, as to what constitutes an arrest, and whereas there was a time when it was held that there could be no lawful arrest unless there was an actual seizing or touching, it is quite clear that that is no longer the law. There may be an arrest by mere words, by saying "I arrest you" without any touching, provided of course that the accused submits and goes with the police officer. Equally it is clear, as it seems to me, that an arrest is constituted when any form of words in used which, in the circumstances, of the case, were calculated to bring to the accused's notice, and did bring to the accused's notice, that he was under compulsion and thereafter he submitted to that compulsion." The above decision fortifies the view that the actual seizing or touching of the body of the person to be arrested is not necessary in a case where the arrester by word brings to the accused's notice that he is under compulsion and thereafter he submits to that compulsion. This is in conformity with the modality of the arrest contemplated under Section 46, Cr.P.C. wherein also it is provided that the submission of a person to be arrested to the custody of the arrester by word or action can amount to the custody of the arrester by word or action (and) can amount to an arrest. The quintessence of the decision in Alderson v. Booth, 1969 2 All ER 271 is that there must be an actual seizing or touching, and in the absence of that, it must be brought to the notice of the person to be arrested that he is under compulsion, and consequent upon it, the said person should submit to that compulsion, and then only the arrest is consummated. Reference also could be made to decision in the State of U.P. v. Deoman, MANU/SC/0060/1960 : 1960CriLJ1504 , in which it has been ruled "submission to the custody by word or action by a person is sufficient" so as to constitute arrest under Section 46, Cr.P.C. In paragraph 57 of the same judgment (at page 1143) : (at p. 1528), it has been observed that, "S. 46, Cr.P.C. provides that in making an arrest, the police officer or other person making the same shall actually touch or confine the body of the person to be arrested unless there be a submission to the custody by word or action." 35. A single Judge of the Gujarat High Court in Kajaji v. State, MANU/KE/0135/1968 has held that the mere surrounding of a person by the police does not amount to his arrest. 36. In effecting a lawful arrest, the arrester should have the power or authority sanctioned by law, to arrest. Otherwise, his action will be wholly without jurisdiction and in such a contingency the person to be arrested has got the right of private defence and can repel the arrest even by violence subject to Section 99, I.P.C. See In re Pedda Munni Reddy MANU/TN/0375/1948 : AIR1948Mad472 and In re Marceda Somaiya MANU/TN/0394/1944 : AIR1945Mad409 . Therefore, in order to have the action of the arrester to be in conformity with the legal and constitutional provisions, it must be an arrest properly and lawfully made in terms of the specified provisions of the Criminal Procedure Code. If it is to be held that the actual seizure or

touching of a person's body with a view to his arrest is not necessary, in order to make his arrest, but that the mere utterance of a guttural word or sound, a gesture of the index finger or hand, the sway of the head or even the flicker of an eye are enough to convey the meaning to the person concerned that he has lost his liberty and brought under arrest, as pointed out by the Division Bench in Kaiser Otmar's case 1981 Mad LW 158 : 1981 Cri LJ 208, then it will not only be in conflict with the modality of arrest prescribed in Section 46 of the Cr.P.C. but also will lead to a startling anomaly and cause serious consequences. Can it be said that a private citizen who is empowered to make the arrest under Section 43, Cr.P.C., can say that he has arrested a person merely by uttering of words or making of a gesture ? Even in the case of a police officer or other officers empowered to arrest, the mere utterance of words or gesture or flickering of eyes, etc., would never amount to an arrest, unless the person concerned submits to the custody of the arrester. 37. In regard to the principles to be applied in interpreting the statutes, there are a number of well recognised authoritative judicial pronouncements about which we would like to refer in this context. In Taylor v. Taylor, 1875 1 Ch D 426, it has been observed thus : "When a statutory power is conferred for the first time upon a Court, and the mode of exercising it is pointed out, it means that no other mode is to be adopted." Applying the above principle, in Nazir Ahmed v. King Emperor MANU/PR/0020/1936, the Judicial Committee made the following observations : "......... where a power is given to do a certain thing in a certain way the thing must be done in that way or not at all. Other methods of performance are necessarily forbidden." 38. The correctness of the decision in Nazir Ahmed v. King Emperor, MANU/PR/0020/1936 has been accepted by the Supreme Court in Shiv Bahadur Singh v. State of Vindhya Pradesh, MANU/SC/0053/1954 : 1954CriLJ910 and Deep Chand v. State of Rajasthan, MANU/SC/0118/1961 : [1962]1SCR662 . 39. Once again, the principle in Nazir Ahmad v. King Emperor, MANU/PR/0020/1936 was reaffirmed by the Supreme Court in State of Uttar Pradesh v. Singhara Singh, MANU/SC/0082/1963 : [1964]4SCR485 wherein a question arose with regard to the admissibility of the oral evidence given by a Second Class Magistrate not specially empowered in matter of recording a confession of guilt made to him by the accused and purported to have been recorded under Section 164, Cr.P.C. In that connection, the Supreme Court, after having stated (at page 266), "The rule adopted in Taylor v. Taylor, (1875) 1 Ch D 426, is well recognised and is founded on sound principle. Its result is that if a statute has conferred a power to do an act and has laid down the method in which that power has to be exercised, it necessarily prohibits the doing of the act in any other manner than that which has been prescribed. The principle behind the rule is that if this were not so, the statutory provision might as well not have been enacted." has finally concluded thus :

"When a statute confers a power on certain judicial officers, that power can obviously be exercised only by those officers. No other officer can exercise that power, for it has not been given to him." In the result, the Supreme Court upheld the view of the High Court in rejecting the oral evidence given by the Magistrate. 40. In yet another case, in Narbada Prasad v. Chhagalal, MANU/SC/0333/1968 : [1969]1SCR499 , the Supreme Court, posing a question for its consideration whether there was power in a Court to dispense with the compliance of the provisions of Section 33(5) of the Representation of the People Act, 1951, answered negatively, holding, "It is well understood rule of the law that if a thing is to be done in a particular manner it must be done in that manner or not at all. Other modes of compliance are excluded." The above principle was re-affirmed by the Supreme Court in State of Gujarat v. Shantilal, MANU/SC/0063/1969 : [1969]3SCR341 while disposing of a civil appeal relating to the acquisition of a land required for the purpose of a Town Planning Scheme. The ratio of that case is as follows : "Land required for any of the purposes of a town planning scheme cannot be acquired otherwise than under the Act, for it is a settled rule of interpretation of statutes that when power is given under a statute to do a certain thing in a certain way, the thing must be done in that way or not at all." 41. Following the well-recognised principle of the interpretation of the statutes, laid down in the above decisions when Section 46, Cr.P.C. is examined, there cannot be a second opinion that the method and the execution of arrest of a person intended to be arrested should be performed only in the manner prescribed in the statute and the other methods of performance are forbidden; otherwise the whole provision of S. 46, Cr.P.C. would be rendered nugatory and functionless. If the method of arrest is not performed in the manner known to law and as prescribed under Section 46, Cr.P.C., but by the mere utterance of words, making of gestures, flickering of eyes, nodding of the head, etc., as ruled in Kaiser Otmar's case, 1981 Mad LW 158 : 1981 Cri LJ 208, we are of the firm view that the modes of arrest prescribed in that ruling are not only contrary to Section 46, Criminal P.C., but will also render the section non-existent or otiose, and such a procedure cannot be adopted to effect a valid arrest. 42. It is now well settled that failure to comply with the requisite procedure would be fatal to the legality of the execution of any act or of the passing of any order by anyone authorised by law. The essence of this principle is reflected in Maneka Gandhi's case MANU/SC/0133/1978 : [1978]2SCR621 wherein it has been held that the procedural safeguards are the essence of liberty. 43. In "Judicial Review of Administrative Action (Third Edition) by S.A. de Smith, at page 122, it is stated thus :

"The law relating to the effect of failure to comply with procedural requirements resembles an inextricable tangle of loose ends." 44. As pointed out in Maneka Gandhi's case MANU/SC/0133/1978 : [1978]2SCR621 , if the statute makes itself clear on any point, then no more question arises; but if the statute is silent, then the law, may, in a given case, make an application and apply the principle of natural justice. 45. In Mager and St. Mellons R.D.C. v. New Port Corporation, 1952 AC 189 Lord Simons said : "The duty of the Court is to interpret the words that the Legislature has used; those words may be ambiguous, but, even if they are, the power and duty of the Court to travel outside them on a voyage of discovery are strictly limited." 46. In Nandini Satpathi's case, MANU/SC/0139/1978 : 1978CriLJ968 their Lordships of the Supreme Court have laid down the proposition of law as follows : "We feel that by successful interpretation judge-centred law must catalyse community-centred legality." We have already expressed that the modality of arrest indicated in Kaiser Otmar's case 1981 MLJ158 : 1981 Cri LJ 208 is not in conformity with Section 46, Cr.P.C., which section by itself is very clear. We feel that the Bench perhaps would not have laid down this dictum regarding the mode of arrest had Section 46, Cr.P.C. been brought to their notice. Further, the Bench has not also adverted to the leading Full Bench decision of this Court in Collector of Customs v. Kotumal, MANU/TN/0218/1967 : AIR1967Mad263 and Harban Singh v. State, MANU/MH/0011/1970 : AIR1970Bom79 touching on this issue. For the reasons stated above, we hold that the rule laid down by the learned Judges constituting the Division Bench, in Kaiser Otmar's case, 1981 Mad LW 158 : 1981 Cri LJ 208 with great respect, with regard to the mode of arrest is not good law. 47. The other question that arises for our consideration in this reference is whether the Customs Officers can detain any person under the guise of an enquiry, interrogation or investigation beyond twenty-four hours before producing him before the Magistrate and whether such a detention would be violative of Article 22 of the Constitution of India. We have launched on a detailed discussion while interpreting the term "custody", which discussion has a bearing on this question. The question of production of a person before a Magistrate within twenty-four hours as envisaged in Article 22(2) of the Constitution of India, would arise only if that person is arrested and detained in custody. 48. Article 22(2) and (3) of the Constitution of India reads thus : "22(2). Every person who is arrested and detained in custody shall be produced before the nearest Magistrate within a period of twenty-four hours of such arrest excluding the time necessary for the journey from the place of arrest to the Court of the Magistrate and no such person shall be detained in custody beyond the said period without the authority of a Magistrate.